Canada's First World War Internment Operations

Canada's First World War Internment Operations

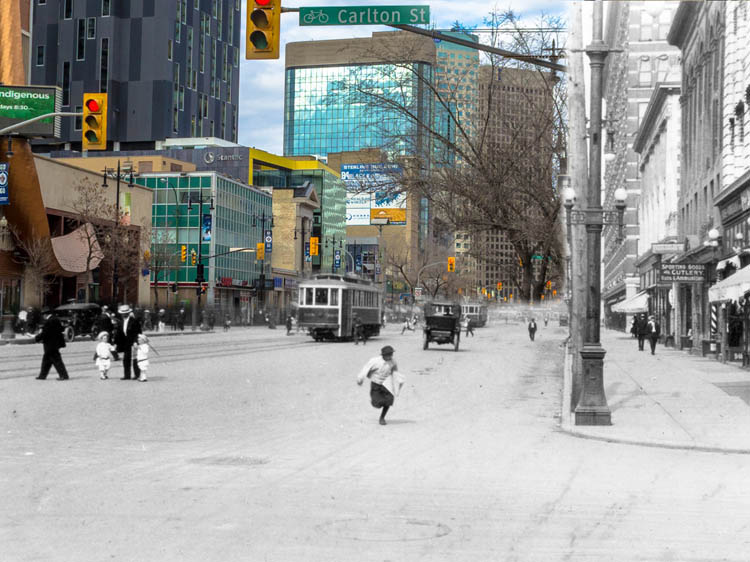

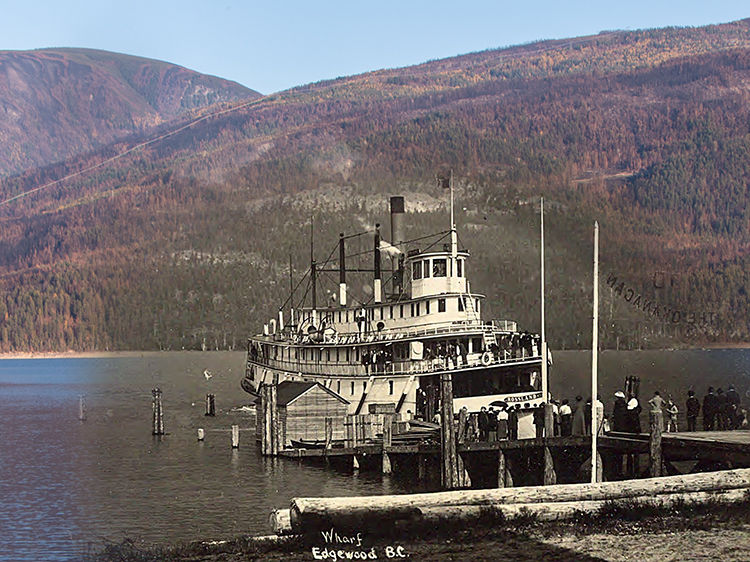

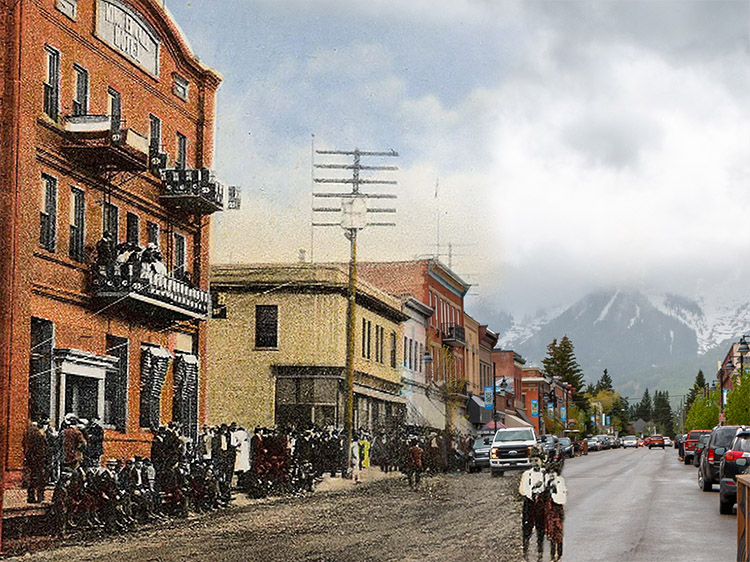

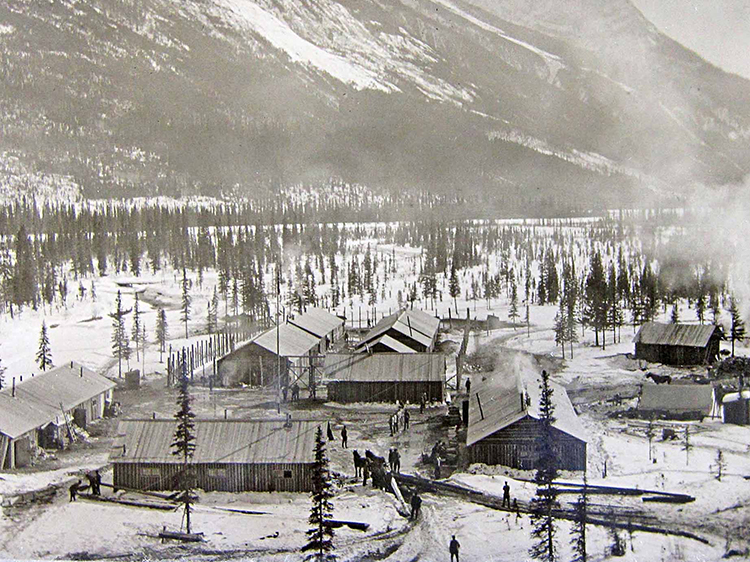

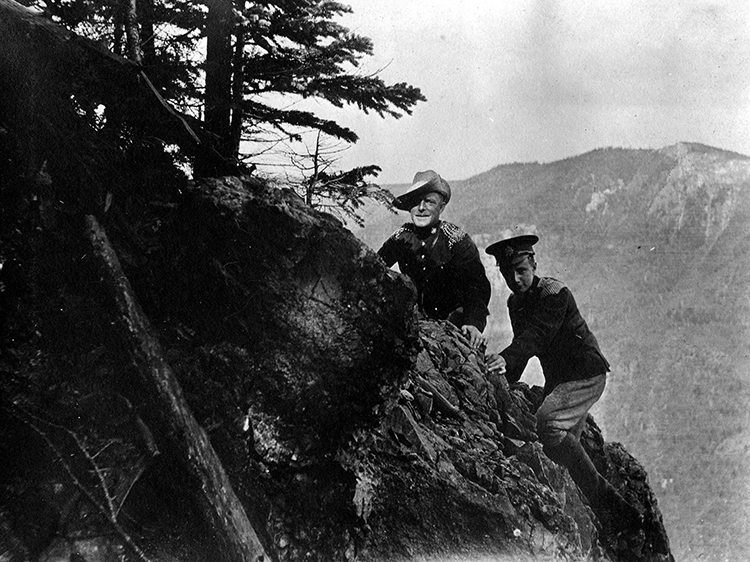

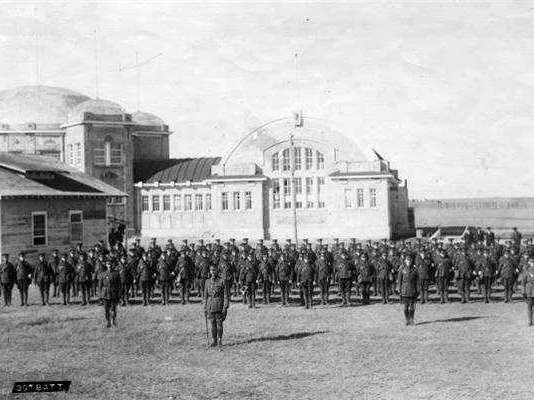

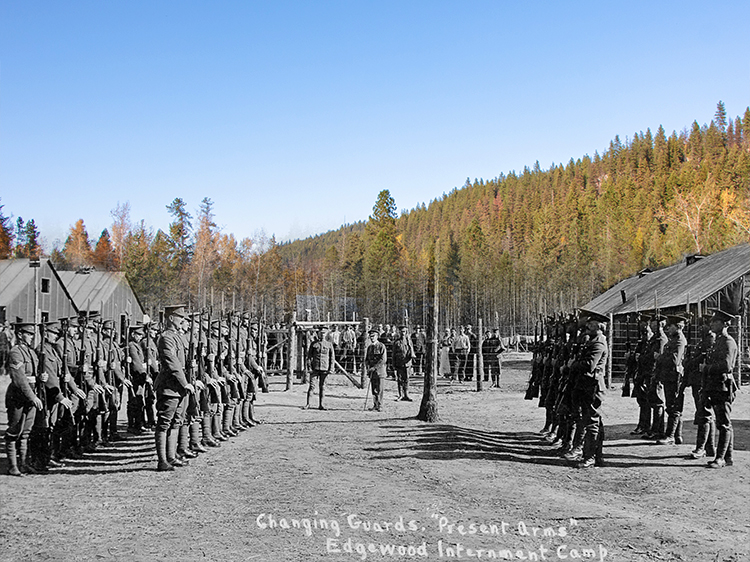

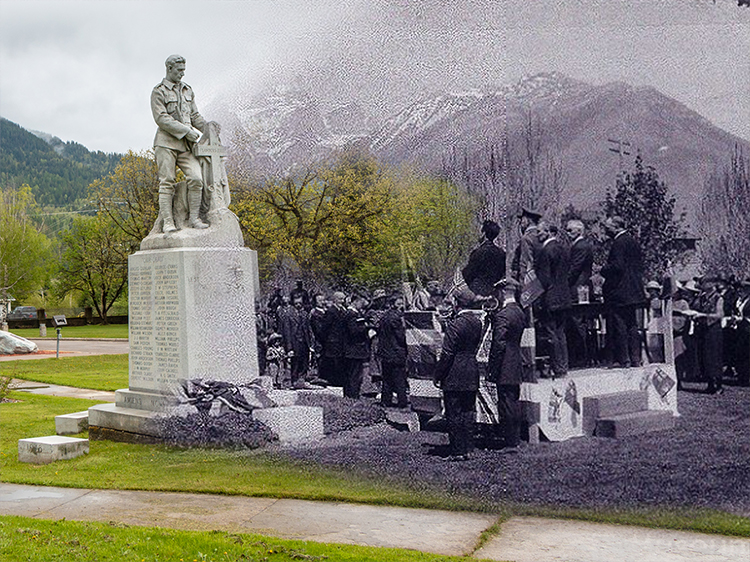

During the First World War the Canadian government established a network of 24 internment camps and receiving stations to imprison immigrants from enemy countries who were designated "enemy aliens." 8,759 people were interned between 1914 and 1920. Almost two-thirds were civilians living in Canada who'd committed no crime except being born in an enemy nation.

The victims of internment included Ukrainians, Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians, Romanians, Turks, Jew, Russians, and Italians. The majority of internees were Ukrainian.

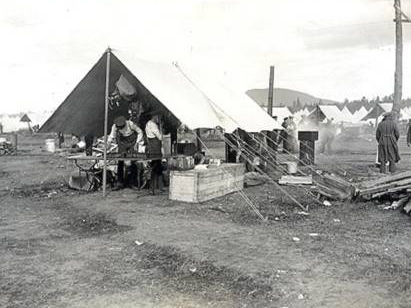

They were made to do forced labour in sub-zero temperatures in remote camps. The conditions were appalling. The guards meted out arbitrary punishments and physical abuse. Some were tortured. 107 prisoners died in captivity. The humiliating and nightmarish experience left mental scars on many survivors.

A further 80,000 civilians were forced to register with the police and had their civil rights sharply curtailed. Tens of thousands more were fired from their jobs, had their property seized, and lost their right to vote.

Efforts to Remember

Few of the survivors ever spoke of their experiences, and this dark chapter in Canadian history was largely forgotten. In 1954 the National Archives of Canada destroyed almost all records of these events.

Efforts to gain recognition for Canada's first national internment operations began in 1978 when Nick Sakaliuk gave testimony to historians about his experience of internment. Many survivors and their children began to come forward with their own stories.

In November 2005, Parliament passed the Internment of Persons of Ukrainian Origin Recognition Act, which finally recognized these historic injustices. In 2008, representatives of the Ukrainian Community agreed with the Canadian Government to create the Canadian First World Internment Recognition Fund which would support commemorative, educational, scholarly and cultural projects that reminded Canadians of this dark chapter in our history.

This series of tours, created by On This Spot in partnership with the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund aims to raise awareness of these events and the experiences of those affected. All the tours are available in English and French in both audio and text formats.