Brandon is Manitoba's second-largest city. It was incorporated as a city in 1882, though its origins as a fur trade post date back far earlier, trading with the Indigenous peoples of the Plains, such as the Sioux. Its modern foundation occurred during the rush of settlers that followed in the path of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The population grew rapidly, and it quickly became a service hub for the region. During the First World War, Brandon's Exhibition Building was used as an internment camp for enemy aliens. Today the Exhibition Building has been replaced by the headquarters of the Brandon Police Service.

This project was developed by the Brandon General Museum & Archives and funded by the Province of Manitoba through the Department of Sport, Culture, Heritage and Tourism and their Community Museum Project Support Program. The component on Brandon's First World War Internment Operations was possible thanks to a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

We acknowledge that Brandon is located on Treaty 2 Lands. These are the traditional homelands of the Dakota, Anishanabek, Oji-Cree, Cree, Dene, and Metis peoples.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Explore

Brandon

Stories

Brandon Internment Camp

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Assoc.

Story Location

Those seeking help from the Brandon Police Service are today welcomed into a modern facility at 1020 Victoria Avenue, surrounded by a nicely landscaped parking lot. Flower gardens add some beauty to what is otherwise a sea of asphalt, and prisoners being taken into custody here can at least be assured that their quarters will afford them some level of dignity – a testament to how far Canada has come from the early twentieth century, when xenophobia combined with a number of other social, political, and economic factors to lay the groundwork for the internment camp once located where the Brandon Police Service’s headquarters is now situated.

* * *

As with many of the so-called “camps,” that in Brandon amounted to an existing structure repurposed to accommodate prisoners of war. Starting in September of 1914 and continuing through the summer of 1916, the sprawling Winter Fair building on this site housed up to a thousand men who were deemed to be “enemy aliens” on account of their cultural heritage.1

The ironies associated with internment are apparent in contemporary reportage of these men arriving in Brandon. “As the train drew to a stop the crowd waited eagerly to get a glimpse of the Germans and Austrians who have gathered from all parts of the Canadian West and who will be safely taken care of while the war lasts,” the Brandon Daily Sun informed its readers on November 27 1914.2

Of course, care and safety were too often the furthest thing from the minds of those entrusted with the care of these prisoners. While efforts were made to ensure efficient evacuation of the premises in the event of fire, the building itself undermined both the physical and mental health of internees.

This was most glaringly apparent when Peter Duclo and a companion by the name of Barozchuck attempted to escape from the Brandon camp on May 29, 1915. Duclo jumped from a window fourteen feet into a concrete sidewalk, injuring his ankle.3 Not quite a week later, some fifteen “enemy aliens” made a dash for freedom after cutting through the floorboards beneath a table at which they had been playing chequers. The alarm was raised, and the men were shot or assaulted as they attempted to escape. Mike Butryn and Andrew Grapko ended up in hospital, the former “hovering between life and death” on account of his injuries.4 While this was not unexpected in the context of war, it revealed the risks internees ran in their quest to escape the drudgery of imprisonment. Simon Konrat, a 24 year-old Austrian, undoubtedly spoke for all of his fellow internees when he informed a correspondent for the Sun that “another two months of the monotonous life at the Arena would drive him crazy.”5

Even so, General W.D. Otter was most impressed by the facility when he paid it a visit in the spring of 1915. According to the March 5 1915 edition of the Brandon Daily Sun, Otter made it plain to the officers in charge of the Brandon internment camp “that they had the best layout for barracks, the best arrangements for handling interned men, and the best quarters for the latter in the whole Dominion.”6

For those citizens of Brandon who lined the railway tracks to catch a glimpse of those being committed to their enormous winter fair building, “enemy aliens” would be entrusted to the safekeeping of professional soldiers “doing their bit” for King and Country. For those stepping off the arriving train, internment would be an experience of contradiction and irony: the same country which welcomed immigrants and promised to look after them would in fact turn against them.7

2. “Prisoners of War Arrived In City This Afternoon,” Brandon Daily Sun, November 27, 1914.

3. “War Prisoners Break For Liberty, One Gains Freedom,” Brandon Daily Sun, May 31, 1915.

4. “15 Alien Enemies At Brandon Make Dash For Freedom,” Brandon Daily Sun, June 7, 1915.

5. Ibid, June 7, 1915.

6. “Brandon Has Best Arrangement For Interned Aliens,” Brandon Daily Sun, March 5, 1915.

7. Bohdan S. Kordan, “Behind Canadian Barbed Wire: The Policy, Process, and Practice of Internment,” in No Free Man: Canada, The Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016),Pgs. 130-131, 172-176, 186-187.

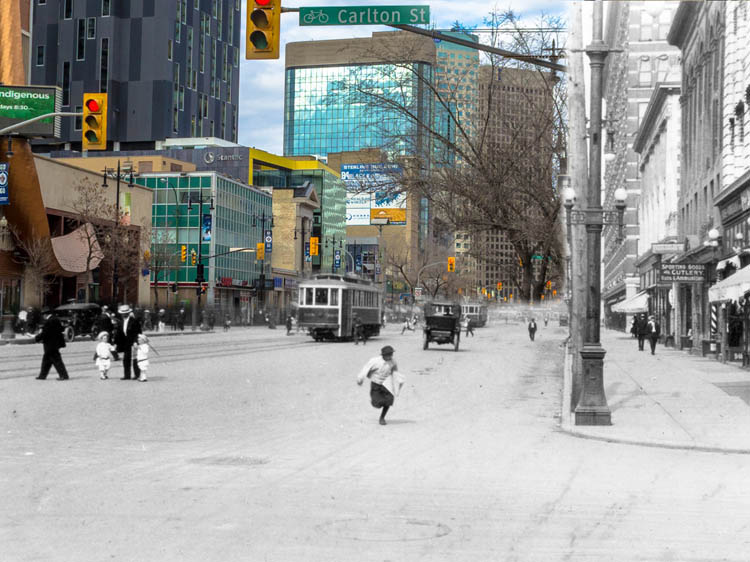

Then and Now Photos

Reesor's Jewelry

Brandon General Museum and Archives

1883

Before the Town Center was built in the late 70s this block of Rosser was home to “Christie’s Book and School Supplies” and “Reesor’s Jewellery”. Both of which are still active today.

Reesor’s Jewellery opened on this block in 1882 as Brandon’s first jewelry store by David Reesor. The Reesor’s Jewellery Clock originally stood on a pedestal or hung outside of the store’s location here until it was moved to the corner of 9th and Rosser, where it still is today.

Fire Hall No. 1

Brandon General Museum and Archives

c. 1900

The previous fire hall was built here in 1882 and had a tower that resembled St. Mark’s Campanile bell tower located in Venice, Italy. Many Brandonites wrote to the Brandon Sun wanting to keep the 30-year-old tower preserved. Some even claimed it would be a crime or an “act of vandalism” to tear it down.

The cost of the construction caused a lot of debate, as the estimated price kept rising. Eventually the new and improved Central Fire Hall station was opened at the cost of $40,000, over a million dollars by today’s standards.

The Central Fire Hall building was constructed in 1911, replacing a previous fire hall on the same site.

First Central School

Brandon General Museum and Archives

ca. 1900

The First Central School was only active for 20 years. The quickly-growing population of the city demanded for more and bigger schools. Even after adding another two-storey addition in 1884, this building was still very overcrowded. The space also hosted city council meetings until the first city hall was built.

Eventually it was sold in 1903 and the students were moved to other, newly built, schools. Part of Brandon's first schoolhouse can still be seen from 11th Street.

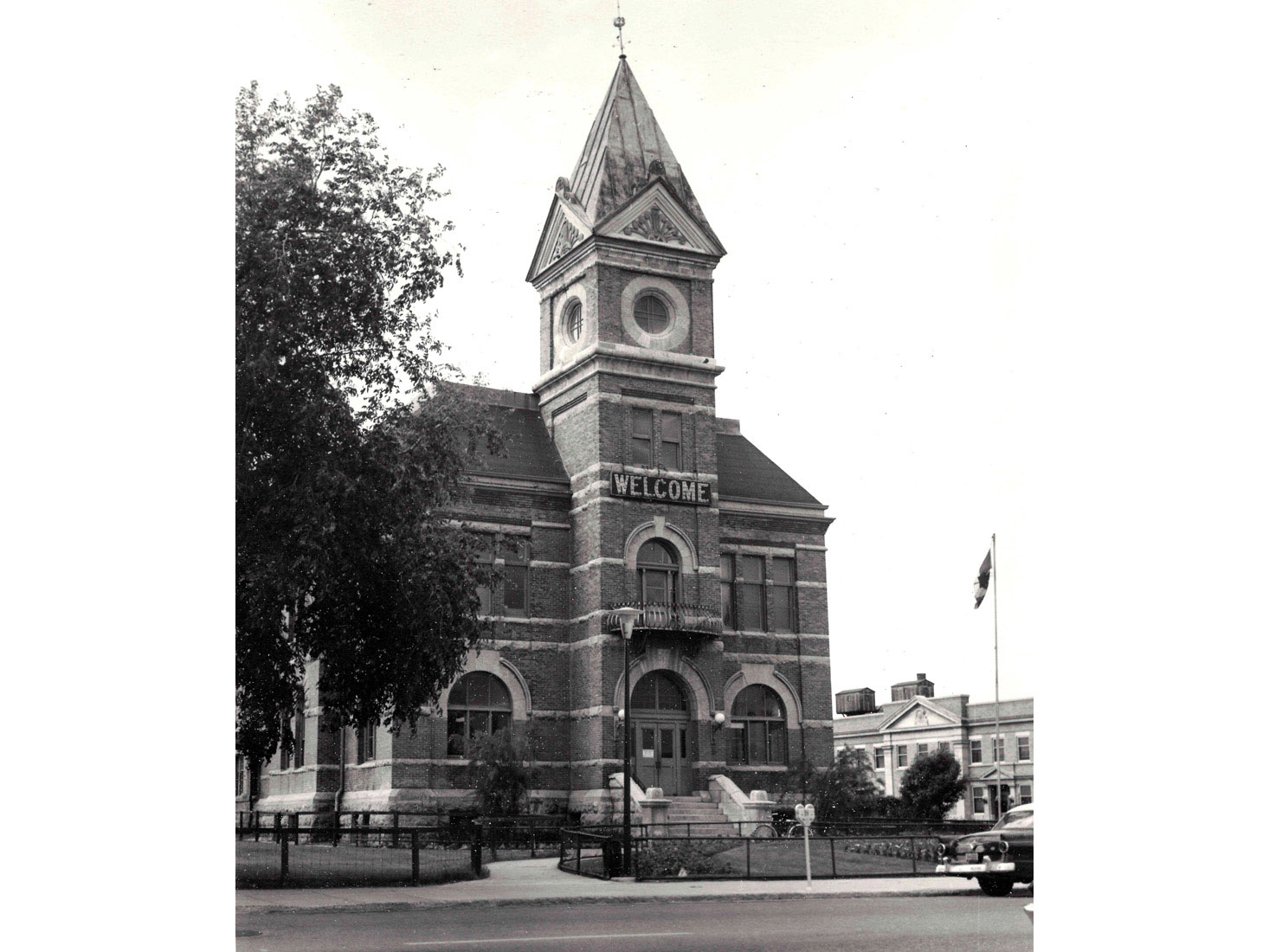

Brandon City Hall

Brandon General Museum and Archives

ca. 1950s

Brandon’s first city hall was built here in 1892. Before it was built, Brandon’s first Mayors and City Council would host meetings at the First Central School (100 block of 10th).

This first City Hall was quite an amazing building – it was two stories and housed an opera house as well as a public market. In 1903, Brandon residents saw their very first moving picture show here at the opera house. The film scenes were projected onto a blanket and were described as “most realistic” in a review by the Brandon Sun.

The building was demolished in 1971 as it was deteriorating beyond the point of repair. The original furnishings from these council chambers are now on display at the Brandon General Museum & Archives, on loan from the Daly House Museum.

Prince Edward Hotel

Brandon General Museum and Archives

1963

The skate park here was once the site of Brandon’s most grand hotel, the Prince Edward Hotel. It also operated as a depot for the CN Rail. The skate park actually reflects the ground floor of the hotel with the word “LOBBY” painted where the entrance would be. The suspended track represents the CN Rail depot.

Built between 1911 and 1912, and opening in early 1912, the Hotel was a grand example of high society and culture, featuring many amenities including fine dining and barroom, a public bath, billiard room, barber shop and even a bake shop.

Travelers and locals alike would frequent the coffee house, restaurant, and attend special events and conferences hosted here. Another element of the day you would find in hotels were “Sample Rooms”. Traveling salesmen would get off the train with their cases of merchandise and set up in a room for interested buyers to come and shop.

Unfortunately, the hotel went bankrupt and closed in 1976 and was demolished in 1980.

In 2009, construction started to make this space a memorial skate park dedicated to Kristopher Cambell, who tragically died in a car accident at the age of 17 in 1996. The grand opening of the skate park took place exactly 15 years later in 2011.