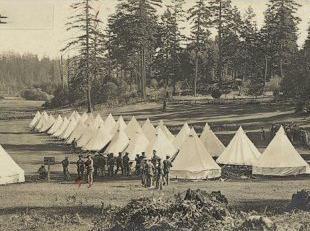

Located just north of Quebec City, the land in this region was first granted by the French crown to Robert Giffard de Moncel in 1647. It reverted to the British Crown in 1800, and in 1816 sold to two Quebec lawyers, who sought to bring Irish and Scottish settlers to the area. A small farming community grew in the area that remains to this day. At the outbreak of the First World War, a massive military training camp was established here that is today called Canadian Forces Base Valcartier. During the war it was the largest military camp in Canada. It was where most contingents of the Canadian Expeditionary Force trained before boarding ships for Europe at the Port of Quebec. During 1915 it was also the site of an internment camp for enemy aliens, who were forced to work expanding and improving the camp.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

We respectfully acknowledge that Valcartier is located on the traditional territories of the Wendake-Nionwentsïo and the Nitassinan (Innu).

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Explore

Valcartier

Stories

Valcartier Internment Camp

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Assoc.

Story Location

The Canadian military base at Valcartier served as an internment camp for 'enemy aliens' between April and October 1915. Enemy aliens were people who had immigrated from countries that Canada went to war with in the First World War. "Enemy alien" was an official legal category, meaning they had almost all their civil liberties stripped away, and were required to register with police and report regularly.

If these people came under suspicion of disloyalty, or were destitute (destitution amongst enemy aliens was criminalized) they were sent to an internment camp. In practice most of the internees were unemployed men of one of the dozen nationalities comprising the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Over half of the total 8,579 internees were Ukrainian.

In 1915 the government had decided to recoup some of the costs of interning these civilians by forcing them to work. A number of forced labour camps were opened from the Rockies to Quebec.

The military found internee labour very helpful in developing the rapidly growing military base at Petawawa, Ontario, and decided they could do the same at the huge new base at Valcartier, just north of Quebec City. By early 1915 the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force had departed the Valcartier camp for Europe, which left it vacant as new troops were being raised.

Thus, starting in April 1915, the Valcartier internment camp received 150 internees from Montreal, 23 from Halifax, and a further 12 from the Beauport Armoury in Quebec City.1 They were put to work digging ditches, laying pipes, and erecting camp buildings.

We have a report of their conditions from the American consul in Quebec City, who visited the site that summer. He wrote that the "actual conditions of the prisoners [are] very good and they are cheerful and contented."

He noted that a "single German of superior intelligence," was made prisoner foreman, and apparently relations between the internees and the camp authorities were good.

The camp closed in October 1915 and the remaining prisoners were dispatched to Spirit Lake, Quebec, or Fort Henry at Kingston, Ontario.