Walking Tour

Vanished Vancouver

The City's Lost Architectural Legacy

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P13

Vancouver is a young city, one of the youngest major cities in the world. Since it was founded, the vast primordial forests of cedar and fir have given way to broad avenues, handsome neighbourhoods, and imposing towers of glass and steel.

The path from there to here has not been a straight one. Vancouver is continuously remaking itself. Buildings are demolished every day and new ones erected in their place. They are usually taller and bigger, but not necessarily better.

Many of Vancouver's best buildings no longer exist. They have been destroyed and replaced, either because the fast-growing city outgrew the building, or because government policies gave short shrift to preserving the city's fascinating architectural heritage. All victims of progress.

In this tour we will look at some of the best buildings that once stood in Vancouver, and learn what happened to them. One hopes that as the years go by, there will not be more additions to this tour.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

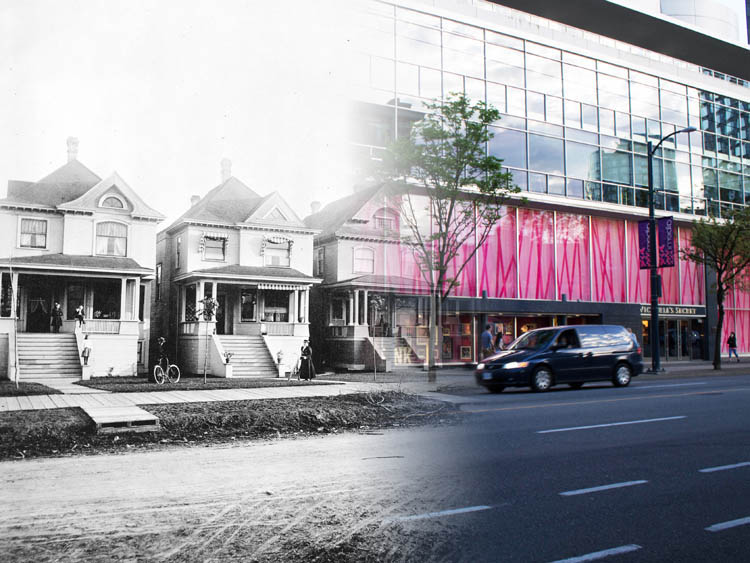

1. "Progress"

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P13

1900

This row of quaint homes on Burrard has been replaced by a commercial building. If you zoom in on the old photo, on the left you can see a couple women getting their bikes out for a ride around town while their children watch from the porch. Over the past 130 years this city's periodic bouts of frenzied growth has led thousands of homes like this—and entire neighbourhoods too—to be erased and replaced. While much of this is part of the inevitable growing pains experienced by any city, a shocking amount has been thoughtless and unnecessary.

* * *

In his book, Vanishing Vancouver: The Last 25 Years, Michael Kluckner despairs at the "disposal of beautiful houses and gardens, cast away as if they didn't have any value at all. That their replacements appeared inferior to my eyes just compounded the outrage. There seemed to be so little appreciation by residents old and new of Vancouver's houses, no environmental or aesthetic mindset that would guide the builders even into preserving trees."1

About 1,000 homes are demolished in Vancouver every year.2

2. A Quieter Time

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: SGN 1596

1917

A fascinating glimpse down Burrard Street at a much quieter time. You can see Christ Church Cathedral across the street, though in the now photo it is unfortunately covered in scaffolding. The building on the left was a five-storey ivy-covered hotel called the Glencoe Lodge. Despite all the big city dreams, as late as the 1980s much of Vancouver still had a small town feel. It was a far cry from the global metropolis people growing up in the city know today.

* * *

For much of the 20th Century Vancouver was destined to remain a provincial city, a far-flung outpost in a very large, very under-populated country. It remained, in some senses, a small town. Streets like this—quiet, tranquil, and often empty—were a common sight. In recent decades the pace of change has quickened.Standing here today, in the middle of Vancouver's hectic financial district, trying to take yourself back to the way this intersection was in 1917 requires an active imagination..

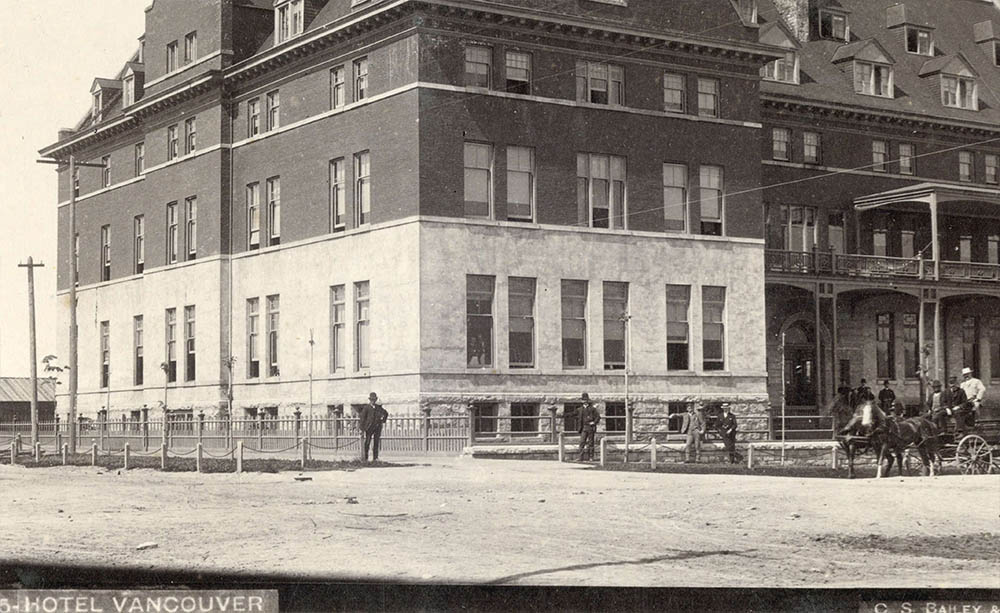

3. Hotel Vancouver (1916-1949)

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-101

1919

On the right in the distance is the Second Hotel Vancouver, a fascinating Romanesque Revival building that dominated Vancouver's skyline for decades. It was eventually made redundant by the Third (and current) Hotel Vancouver and demolished.

* * *

Immensely popular, celebrities like Winston Churchill and Babe Ruth made sure to stay at the Hotel Vancouver when they were in the city. Eventually the CPR decided a newer Hotel Vancouver was needed, and in the 1930s oversaw the construction of the updated Chateau style third Hotel Vancouver hotel across the street from you. During World War II the second Hotel Vancouver was used as a barracks and after the war closed off to the public. When many veterans returning from overseas couldn't find housing in Vancouver they took over the hotel and turned it into veterans housing. In 1948 they were persuaded to leave, and a year later the hotel was finally demolished. It was replaced with a parking lot until the 1960s, when an Eaton's department store was built there. In 2015 the new Nordstrom's store opened on the spot.

4. Medical-Dental Building (1927-1989)

Vancouver Archives AM1517-S1-: 2008-022.040

1950s

Looking back towards the intersection, across the street from the current Hotel Vancouver, and you will see where the Medical-Dental Building once stood. A widely celebrated Art Deco style office building, it was designed by the same architects that gave us the famous Marine Building on Burrard Street. The Medical-Dental Building was demolished in 1989 to make way for the building you see today.

* * *

The architects, John McCarter and George Nairne, had fought in the First World War and McCarter credited a nursing sister with saving his life when he was badly wounded. Mixing nicely with the medical theme (the building housed mostly doctors and dentists offices), 11-foot statues of nursing sisters were placed on the corners of the building.

Charles Shon evidently did not like the Medical-Dental Building and long desired to replace it with a more postmodern building.1 His son, Hong Kong businessman and philanthropist Sir Run Run Shaw succeeded in fulfilling his dream in 1989. Though the angels of the nursing sisters were destroyed when the building was imploded, fibreglass replicas were made and put on the Shaw Tower at Cathedral Place that stands there today.

5. Birks Building (1913-1974)

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-4399

1946

This was the Birks Building, perhaps the saddest example of heritage destruction in Vancouver's history. This building, along with the Vancouver Block, the second Hotel Vancouver, and the Hudson's Bay Company store, all anchored pre-World War I Vancouver at the corner of Granville and Georgia. It was destroyed to make way for the Scotia Tower you see today.

* * *

The Birks jewelry company decided, evidently for fuzzy reasons, to knock it down in the 1970s. The architectural historian Donald Luxton called it an incomparable example of "corporate vandalism."1 That it was to be replaced by the spectacularly unimpressive Scotiabank Tower helped fuel the fury. Thousands of Vancouverites came out to protest the building's destruction, even staging an elaborate mock funeral. It was no use and the Birks Building came down in 1974. The widespread public outrage prompted the government to belatedly strengthen the city's heritage protection laws.

6. Opera House (1891-1969)

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P503.1

1912

People line up outside the Vancouver Opera House that once stood at this spot on Granville Street. It was built by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1891. Unlike the unimposing First Hotel Vancouver, the opera house was far more big and impressive than a city of Vancouver's size merited in those early days. Over the decades it went through a succession of owners and names before finally being demolished to make way for the Eaton's department store.

* * *

In the 1910s it became a vaudeville theatre, showing various live performances, and ended its life as the Lyric Theatre.

7. Hotel Vancouver (1888-1910)

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-375.19

1889

This was the first Hotel Vancouver, built by the Canadian Pacific Railway at what was then a rather empty, backwater part of the city. The CPR picked this intersection at Granville and Georgia as the new centre of the city ahead of Gastown. The plan seems to have worked. The building itself was widely mocked for being ugly and was torn down to be replaced by the second Hotel Vancouver that we've already seen.

* * *

A writer called it "a sort of glorified farmouse."1 One newspaper declared "it resembled a compound of a decayed grist-mill with bits of the bastille and the tower of London added."2 Unsurprisingly, the hotel didn't last long and a second much more impressive one was built on the same spot.

8. Fairfield Building (1898-1949)

Vancouver Archives AM1506-S1-: CVA 447-286

1946

The interesting multi-colour bricks are not visible in this black and white photo of the Fairfield Building. An Italianate-style office building, it was one of many in this part of town that have since been destroyed and replaced with rather less interesting structures.

* * *

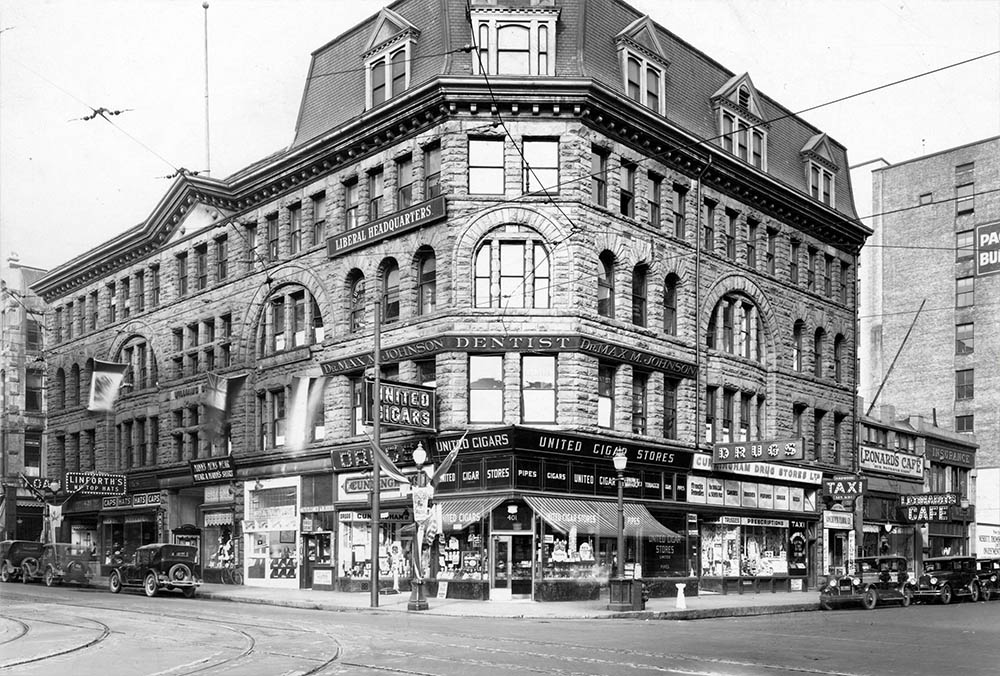

9. MacKinnon Building (1898-1957)

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P646.1

1928

In its time the Mackinnon Building was considered "the finest office building in the city."1 We see it here as headquarters of the Liberal Party during an election campaign. The building that followed, the United Kingdom Building, has a bit more of a subdued modernist style.

* * *

10. CPR Station (1899-1914)

Vancouver Archives AM1589-: CVA 2 - 50

1890s

This striking building once stood at the foot of Granville, the second railway station built by the Canadian Pacific Railway on this spot. The city outgrew the station, and in 1914 it was knocked down and replaced by the other station that stands just to the right of it today.

* * *

The growth was too fast for this station, and the authorities quickly concluded it was too small. It stood for only 15 hectic years before being replaced. Many worthwhile buildings have shared this fate, victims of a city growing faster than most anticipated.

11. Empire Building (1888-1955)

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-4532

1934

The Empire Building was another high-quality Italianate style office building that dated back to the city's first days.

* * *

12. Court House (1890-1911)

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu N13

1893

Victory Square used to be home to Vancouver's first court house. A Palladian style building by Thomas Sorby, who also did the first Hotel Vancouver, the court house was made redundant by the new court house on Georgia and Howe (today's art gallery). It was demolished after the new court house was completed.

* * *

13. Woodward's (1903-2006)

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-635

1900s

On the left is the rump remainder of the world-famous Woodward's department store, one of the biggest department stores in the world in its early 20th Century heyday. After World War II Woodward's fell on hard times and the surrounding neighbourhood decayed. The building had expanded to include most of the block and all but this little section was demolished to make way for a big, new development.

* * *

After World War II people began moving to suburbs and flocking to shopping malls instead, prompting a gradual decline in Woodward's fortunes. Finally in 1993 the company went bankrupt and the store was closed. Many homeless indigenous people, decrying the lack of affordable housing in the Downtown East Side, began squatting in the building. Purchased by developers in 2004, there followed a huge controversy over what to do with the old site. Eventually $400 million was spent on redeveloping the site for housing, some of it ultra-low-rent, and businesses . In a nod to heritage preservation part of the original building was preserved, the part you see above.

14. Pantages Theatre (1918-1967)

Vancouver Archives AM1135-: cva 1135-45

1965

Alexander Pantages became famous across North America for his vaudeville theatres. This was the second in Vancouver he built and it was renamed several times. At the time this photo was taken it was named the Majestic. Just after this photo was taken the theatre was demolished to make way for a parking lot. After that this rather nondescript apartment building you see today was built.

* * *

Radio and film doomed vaudeville as people were presented with a wider array of entertainment options. Vancouver's vaudeville theatres struggled on, some converting to movie theatres, but the great majority went out of business. The one you see here was one of the last to go. Few examples of vaudeville theatres survive in the city.

Endnotes

1. "Progress"

1. Kluckner, Michael. Vanishing Vancouver 25 years. Vancouver: Whitecap Books, 2012. P. 6.

2. Howell, Mike. " Almost 1,000 homes per year slated for demolition in Vancouver." Vancouver Courier. 12 Feb. 2016. Online.

2. A Quieter Time

1. Desjardins, Jeff. "Vancouver's Real Estate Mania." Visual Capitalist. 2 June 2016.

4. Medical-Dental Building (1927-1989)

1. Cathedral Place. "Profile." Online.

5. Birks Building (1913-1974)

1. Luxton.

6. Opera House (1891-1969)

1. "Vancouver City. Its Wonderful History and Future Prospects." Vancouver World. 1891. P. 13.

7. Hotel Vancouver (1888-1910)

1. Luxton.

2. Changing Vancouver. "First Hotel Vancouver – Granville and Georgia." 4 Apr. 2012. Online.

9. MacKinnon Building (1898-1957)

1. Luxton.

10. CPR Station (1899-1914)

1. Government of Canada. "1891 Census." and "1911 Census."

11. Empire Building (1888-1955)

2. Luxton, 165.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Cathedral Place. "Profile." Online.

Changing Vancouver. "First Hotel Vancouver – Granville and Georgia." 4 Apr. 2012. Online.

Desjardins, Jeff. "Vancouver's Real Estate Mania." Visual Capitalist. 2 June 2016.

Government of Canada. "1891 Census." and "1911 Census." Online.

Howell, Mike. " Almost 1,000 homes per year slated for demolition in Vancouver." Vancouver Courier. 12 Feb. 2016. Online.

Kluckner, Michael. Vanishing Vancouver 25 years. Vancouver: Whitecap Books, 2012.

Vancouver World. "Vancouver City. Its Wonderful History and Future Prospects." 1891. Online.