Walking Tour

Stanley Park's Seawall

The Jewel of Vancouver

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: F06-: CVA 1376-80.33

Stanley Park is often called the jewel of Vancouver. The park is a huge patch of temperate rainforest located just beside the downtown core. Ringed by a seawall that offers spectacular views of the city and the North Shore mountains, it's small wonder that Tripadvisor continues to rate Stanley Park the best park in the world.

With this tour you can experience the Stanley Park seawall in an exciting new way, peering into the past to see the fascinating changes the park has undergone since its founding over a century ago.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. Jewel of Vancouver

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Arch P52

1890

This was the entrance arch to Stanley Park a century ago, though the landscape has been reshaped. Stanley Park was established at the first meeting of Vancouver City Council on May 12, 1886. Before that it had been a military reserve, so the council voted to lease it from the federal government for a dollar a year. It was an act of inspired foresight (though it may have also been an act of real estate speculation), and today this city is so much the greater for that first meeting of City Council.

* * *

"The park is our most valuable and integral asset.

"Other cities can boast of urban green space — London has Hyde Park, New York Central Park and even Toronto has High Park.

"But has any a stretch of ground so integral, so central to its self-image as our idyllic cynosure?

"Can you imagine Vancouver without Stanley Park?

"It would lose a huge bit of its soul and become just another seaside burg with a mountain view."1

2. The Rowing Club

Vancouver Archives AM1584-: CVA 7-212

1909

This is the old rowing club, which was located just a bit further east along Coal Harbour than the current one. A floating building subject to changes in the weather, it was replaced in 1911 by the new building you see on the left today.

* * *

3. The Causeway

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: St Pk P56

1916

A barge is dredging up the seafloor to create a causeway connecting Stanley Park to the city. Stanley Park had initially been almost an island, reachable from the downtown peninsula only at low tide. A small bridge had been built over to the park, but it was far too small to cope with all the traffic.

* * *

Before the causeway Lost Lagoon on the other side of the causeway had been a tidal flat. Pauline Johnson dubbed it Lost Lagoon because the lagoon would disappear at low tide. After the causeway was built however the lagoon was made into a permanent lake.

4. Squatters

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-228

1914

When the park was created in the 1880s none of the people who lived within it were actually consulted. There was two villages Squamish First Nations and another village of squatters who steadfastly refused to relocate. We can see some of the squatters homes here along the waterfront. Finally in the 1920s, the city had them legally evicted.

* * *

Afterwards the squatters rebuilt and defied all attempts by the city to make them leave. Finally by 1921 the city took the squatters to court, demanding evidence of 60 years of continuous habitation of the land. The squatters had no written deeds to prove their claim and in 1931 they were finally evicted. There were a couple exceptions, like the Cummings family, who were allowed to continue living in the park until their deaths in the 1950s.

5. The Seawall

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: F06-: CVA 1376-80.33

1910

This rather moody photo gives Stanley Park a silent and mysterious air, the man on the bench appears to be watching someone climbing off the seawall and down into the water. The narrow dirt track has since been reshaped into a seawall and a road bringing thousands more people to the park every day.

* * *

6. Nine O'Clock Gun

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1645

1943

For over a century this gun has been a landmark at Brockton Point. Forged in Woolwich Arsenal just outside of London in 1816, it was eventually dispatched to Vancouver Island in the 1850s. In 1894 it made its way over to Vancouver and installed here.

* * *

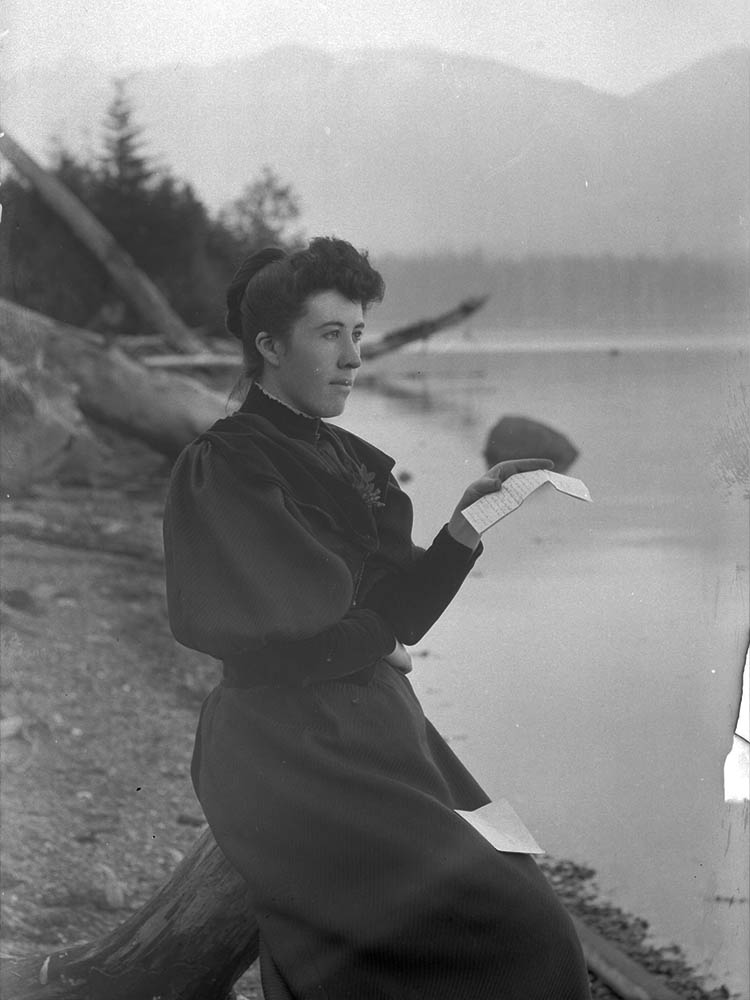

7. The Photography Craze

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: SGN 72

1892

A woman identified as Mrs. H.W. Maynard sits on a tree stump near Brockton Point. There are a few other photos of her posing in the latest 1890s fashions in Stanley Park. It's hard to overstate the excitement cameras caused as they became easier to use and cheaper to acquire. It's hardly surprising that many early camera enthusiasts took to Stanley Park to have their photos taken.

* * *

By the 1890s however cameras were downsizing dramatically and becoming easy enough for anyone to use. People were also enchanted by the amazingly high quality of the photos. Since most of the old photos we do see are low-quality reproductions in books and on websites, most people don't realize that many types of old photos had a far higher resolution than most digital photographs do today. Some of the many competing camera technologies a century ago actually had resolutions thousands of times higher than most digital cameras do today. Most DSLRs today have a resolution of about 20 megapixels, or about 20 million pixels. A daguerreotype from the 19th Century had an absolutely astonishing resolution of 100,000 megapixels, or 100 billion individual pixels in an image. It is still beyond our technical capabilities to easily reproduce the unbelievably high resolution of daguerreotypes.2

8. The Seabus

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bo P533.1

1904

An early sea bus ferrying people between across Burrard Inlet passes Brockton Point. Europeans had been settling the North Shore for as long as they'd been settling Vancouver, but it was not until the 1920s that a bridge connected the two communities. Until then people had to rely on ferries like this to cross the Burrard Inlet.

* * *

9. Xwayxway Village

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-2213

1897

Here we see a rare photo of a Squamish family getting in their dug-out canoes. Just west of here, towards the narrows, was a Squamish village called Khwaykhway. Archaeological evidence shows the Squamish people lived in this place for at least 3,000 years. It was but one of many villages that dotted the coasts all around this region.

* * *

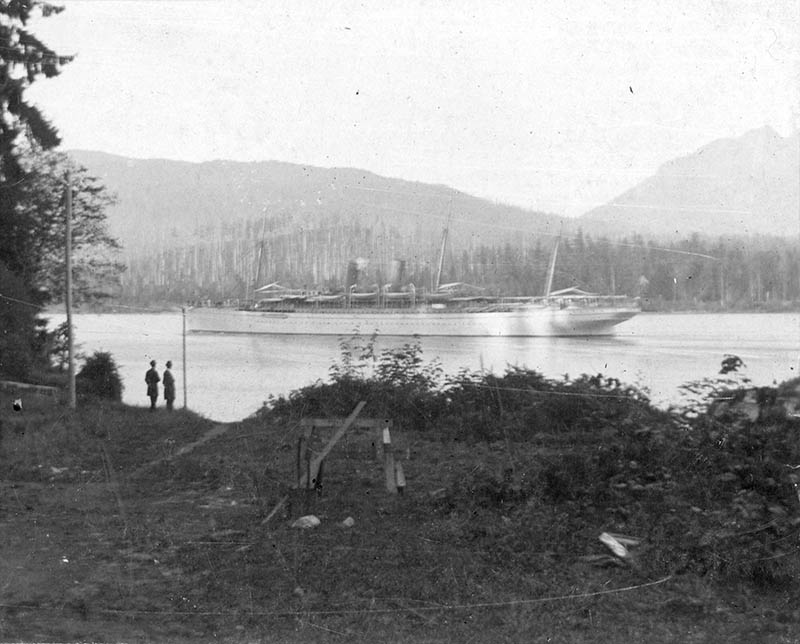

10. Empress of Japan

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bo N83.2

1936

A woman stands by the figurehead of the Empress of Japan, an ocean liner commissioned by the Canadian Pacific Railway to run a mail service between Liverpool and Hong Kong via Vancouver. The ship was scrapped in 1926, but the Vancouver Daily Province paid to save the figurehead and mounted it for display here. The wooden figurehead began to rot and a fibreglass replica replaced it in 1960.

* * *

11. Empress of India

Vancouver Archives AM1506-S1-: CVA 447-5

1895

And here we see the Empress of Japan's sister ship, the Empress of India leaving Vancouver harbour on its way across the Pacific. A couple men at the top of the Pipeline Road have taken a moment to stop and watch its departure.

* * *

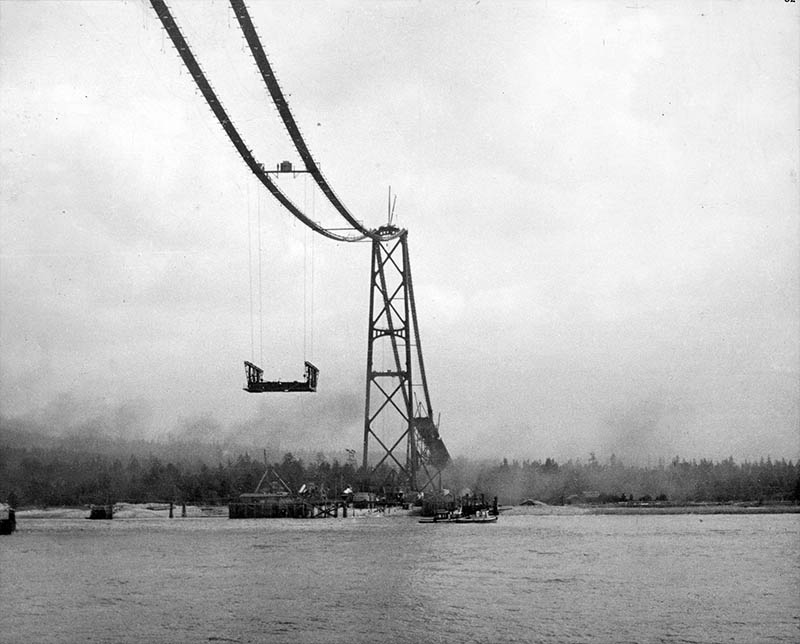

12. The Lions Gate Bridge

Vancouver Archives AM54-S9---: CVA 265-62

1938

Here we can see the first section of the Lions Gate's bridge deck is being lifted into place. The iconic bridge was a technical marvel when it was completed in 1938, and caused a population boom in West and North Vancouver. The biggest investor was actually the beer-brewing Guinness family, who had purchased much of the land in West Vancouver and hoped a bridge would drive up the value of their holdings. Given the price of land in West Vancouver now (much of which they still own), it was an investment that's paid handsome returns.

* * *

It was decided to name the bridge the Lions Gate, after the landmark Lions peaks that can be seen from much of Vancouver. Two art deco style lions were put at the Stanley Park entrance to the bridge. When completed a toll of $0.25 was charged for each crossing car. The bridge proved so popular that the toll brought in enough revenue to pay off the initial investment and it was eventually scrapped in 1963.

13. Prospect Point Lighthouse

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: SGN 1620

1918

A ferry can be seen passing the old Prospect Point lighthouse in the Narrows. You can see the seawall has not yet been built, though there is a walkway from the left providing access. The lighthouse was necessary because of the strong currents in the narrows that doomed many ships.

* * *

14. The SS Beaver

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: LGN 461

1889

Men are standing on the SS Beaver after it has been wrecked at Prospect Point. The little paddlewheel steamer may not look like much to us, but it played a huge role in the early European settlement of British Columbia. Over its 53 years of service the Beaver was present at practically every major event in the province's history. When leaving Vancouver harbour on July 25, 1888, the crew was drunk and managed to slam steamer into Prospect Point. It was impossible to refloat the ship and it was stripped down by souvenir hunters and left on the spot until it finally slipped beneath the waves a few years later. The wreck is still down there, just below where you are standing.

* * *

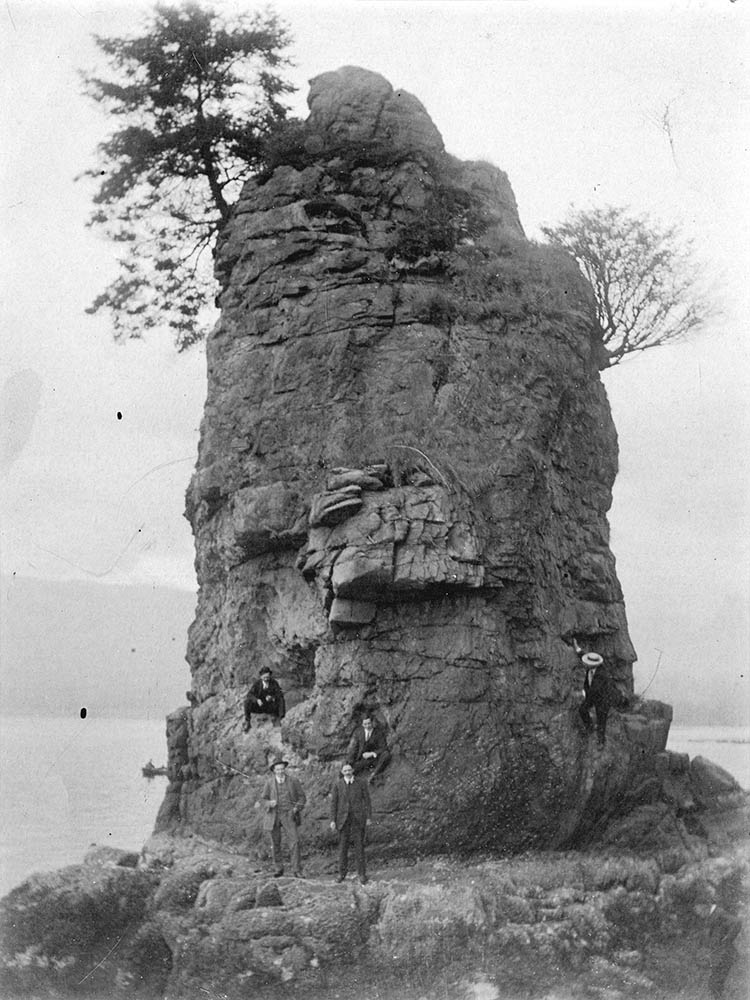

15. Siwash Rock

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-118

1918

This is the famous Siwash Rock, a Stanley Park landmark that was formed over 32 million years ago by a volcanic dike. The poet Pauline Johnson wrote in Legends of Vancouver that it was "like a noble-spirited, upright warrior." She recounts a Squamish legend of the rock where it symbolizes a selfless father.

* * *

"Thousands of years ago, a young chief named Skalsh married a young lady from B.C.’s north coast and they wanted to start a family. The night before Skalsh’s child was to be born, he and his wife swam in the waters of Burrard Narrows to purify themselves, as custom, in preparation for birth. When his wife crept into the forest of Xwayxway as the Squamish call Stanley Park, Skalsh continued to swim to purify himself and his family as his child entered the world. "Challenged by gods to stop swimming and move out of the way of their holy canoe, Skalsh continued to swim to purify himself for the sake of his family. To commemorate his bravery and commitment to family, the gods transformed him into stone when he swam back to shore, towards his wife and child at dawn. The rocky stand serves as a symbol of ‘clean fatherhood’ according to Johnson’s account of Squamish creation story."1

16. Third Beach

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-4570

1946

Here we see crowds of people relaxing on Third Beach. This stretch of beach was once very rocky, but in the 1930s sand was trucked in to make it a more enjoyable place for people to relax.

* * *

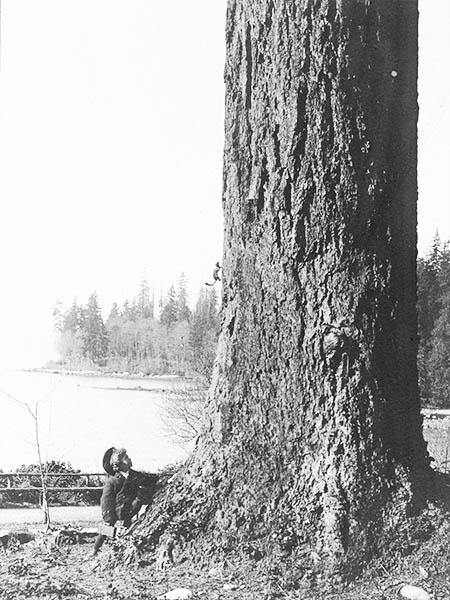

17. Squirrels

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-664

1902

A little boy watches a squirrel scamper up a Douglas fir. It's interesting to note his little hat and lunchbox.

* * *

They tend to be particularly dangerous to the Garry Oak ecosystems found on Vancouver Island and like to pray on bird eggs and nestlings.1

18. Second Beach

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: VLP 144

1907

This is a view of a rocky Second Beach before it was filled in with sand in the 1920s and 1930s, making it much more suitable for swimming.

* * *

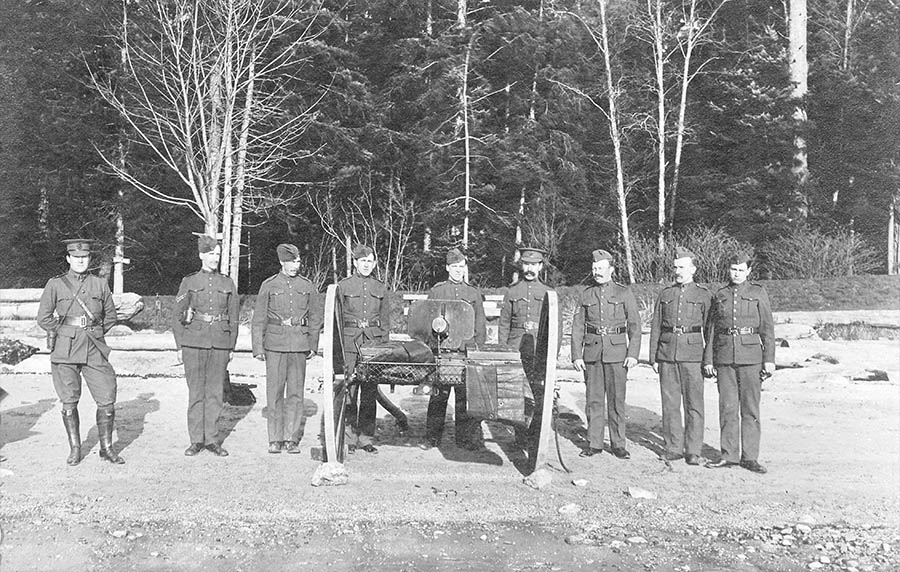

19. Trying out a Maxim Gun

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Mil P222

1909

Troops from the militia try out a Maxim gun at Second Beach. The Maxim Gun, the first real machine gun, was invented in 1883 and in the years afterwards gradually adopted by the great armies of the world.

* * *

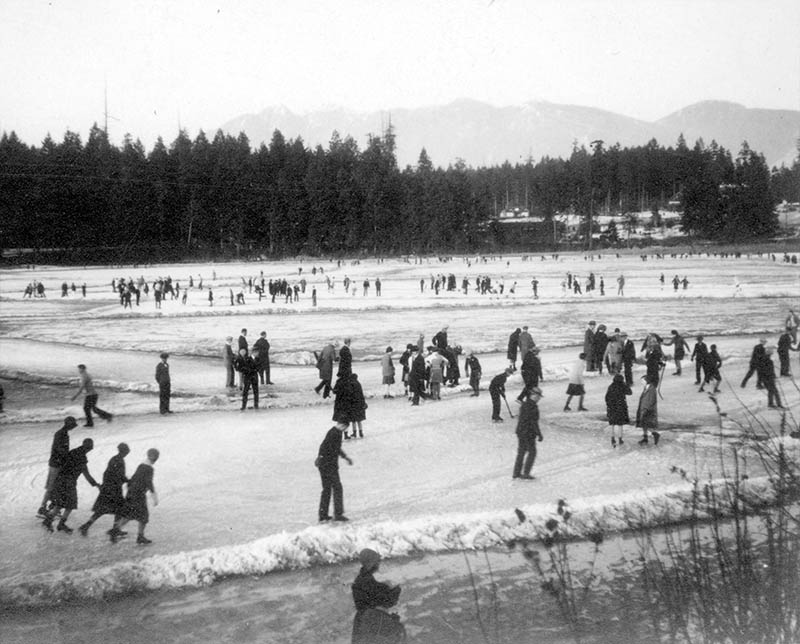

20. Pick-up Hockey

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-669

1930s

Dozens of people are skating on Lost Lagoon, including some boys in the foreground playing a game of pick-up hockey. Governor General Lord Stanley, who gave his name to this park and dedicated it in the 1890s, was also a huge hockey fan and gave his name to the ultimate trophy in competitive hockey.

* * *

Endnotes

1. Jewel of Vancouver

1. Mulgrew, Ian. "Stanley Park is a huge part of Vancouver's soul." National Post. 21 Apr. 2013.

3. The Causeway

1. Davis, Chuck. Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Coastal Publishing, 2011.

7. The Photography Craze

1. Curto, Jeff. "Light and Likeness: Portrait Photography." Photo History Class Sessions. 7 February 2014. Audio.

2. Boyd, Sarah. "On Photography Filters in the Digital Age." Ethos Digital Review. 11 July 2014. Online.

8. The Seabus

1. Davis.

9. Xwayxway Village

1. Suttles, Wayne. Musqueam Reference Grammar. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004, P. 571.

2. Barman, Jean. Stanley Park's Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brocton Point. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2005. P. 21.

10. Empress of Japan

1. Mowbray, Tate. Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes. Cranbury: Cornwall Books, 1986. P. 235.

11. Empress of India

1. Statistics Canada. "Census Profile, West Vancouver." 2011. Online.

13. Prospect Point Lighthouse

1. Lighthouse Friends. "Prospect Point, BC." Online.

14. The SS Beaver

1. Davis.

15. Siwash Rock

1. Post, Miranda. "History of Siwash Rock." Inside Vancouver. 22 Aug. 2013. Online.

17. Squirrels

1. Royal BC Museum. "Aliens Among Us: Eastern Grey Squirrel." 2014.

19. Trying out a Maxim Gun

1. Keegan, John. The First World War. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1998. P. 45.

Bibliography

Bibliography

Barman, Jean. Stanley Park's Secret: The Forgotten Families of Whoi Whoi, Kanaka Ranch and Brocton Point. Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2005.

Boyd, Sarah. "On Photography Filters in the Digital Age." Ethos Digital Review. 11 July 2014. Online.

Curto, Jeff. "Light and Likeness: Portrait Photography." Photo History Class Sessions. 7 February 2014. Audio.

Davis, Chuck. Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Coastal Publishing, 2011.

Keegan, John. The First World War. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 1998.

Lighthouse Friends. "Prospect Point, BC." Online.

Mowbray, Tate. Transpacific Steam: The Story of Steam Navigation from the Pacific Coast of North America to the Far East and the Antipodes. Cranbury: Cornwall Books, 1986. P. 235.

Mulgrew, Ian. "Stanley Park is a huge part of Vancouver's soul." National Post. 21 Apr. 2013.

Post, Miranda. "History of Siwash Rock." Inside Vancouver. 22 Aug. 2013. Online.

Royal BC Museum. "Aliens Among Us: Eastern Grey Squirrel." 2014.

Suttles, Wayne. Musqueam Reference Grammar. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2004,

Statistics Canada. "Census Profile, West Vancouver." 2011. Online.