Walking Tour

Practicing for D-Day

Experiencing an Amphibious Assault

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S3-: CVA 1184-1223

It may seem odd to have a walking tour in peaceful Vancouver that examines amphibious invasions. History records no battles here, let alone a combined arms assault on a defended shore. As one historian noted, "No patch of ground has been so thoroughly unfought for as the Lower Mainland of British Columbia."1 Despite the tranquility of our corner of the world, two amphibious invasions still loom gigantic in the collective memory of Canadians: the disastrous Dieppe Raid of August 19, 1942, and the triumphant D-Day landings on June 6, 1944.

In the collections of the Vancouver Archives there is a remarkable collection of photos from the spring of 1943. They show the events of D-Day and Dieppe playing out in miniature on Kitsilano Beach as Canadian troops stormed ashore in a mock amphibious assault. The dozen or so photos included in this tour hint at the almost sporting atmosphere that prevailed that day, showing war as the government intended people to see it: scrubbed clean of the blood and the misery, the deafening shellfire and the screams of the dying.

An amphibious assault against a defended enemy shore is the most complex--and riskiest—military operation that can be undertaken. Success depends on the most careful and expert coordination of ships, aircraft and the men going ashore. The terrifying uncertainty of what lay before those men in the assault boats when the ramp dropped has fascinated us ever since.

Though a continent and an ocean away from the beaches of France, we will use these photos to examine the techniques and technology of the major amphibious landings that involved Canadians in France: Dieppe and D-Day and hear the harrowing stories of those who took part.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. The Situation in 1943

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1212

1943

Smoke dischargers partially obscure landing craft as they approach Kitsilano Beach. If you look carefully you can see at the centre left that a news-reel camera recording the event has been scratched out by a censor. This exercise would be filmed and shown in theatres across Canada, giving the public an idea of what an amphibious assault entailed.

* * *

Vancouver was a city mobilized for war. In June 1942 fears of looming Japanese attack reached hysterical proportions after the Japanese seized two of the Aleutian Islands in Alaska and a submarine surfaced off northern Vancouver Island and shelled a remote lighthouse. 23,000 Japanese-Canadians were rounded up and exiled to the interior and a black-out was imposed at night. 30,000 troops were raised and stationed across British Columbia. Compare that to the 23,000 full-time soldiers in the Canadian Army today.2 3

Though the risk of Japanese invasion had receded by this time, the fact precious military resources like landing craft, armoured vehicles and anti-aircraft guns were still positioned around Vancouver indicates the threat was still being taken seriously.

2. Worst Case Scenario

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S3-: CVA 1184-1223

1943

Troops pour ashore from their landing craft, sprinting towards a thin strand of barbed wire strung across the beach. One soldier in the foreground already appears to be playing dead. In August 1942, less than a year before these photos were taken, 5,000 Canadians landed at the quiet sea-side town of Dieppe in France. The first major amphibious assault since Gallipoli in 1915, the Dieppe Raid was an unmitigated disaster. Almost 1,000 Canadians were killed and several thousand more were marched into captivity.

* * *

The men in our boat crouched low. Then the ramp went down and the first infantry-men poured out. They plunged into about two feet of water and machine-gun bullets laced into them. Bodies piled up on the ramp. Some men staggered to the beach.

I was near the stern and to one side. Looking out the open bow, I saw 60 or 70 bodies, men cut down before they could fire a shot. A dozen Canadians were running along the beach toward the 12-foot-high seawall, 100 yards long. Some fired as they ran. Some had no helmets. Some were wounded, their uniforms torn and bloody. One by one they were hit and rolled down the slope to the sea.

I don't know how long we were nosed down on that beach. It may have been five minutes. It may have been 20. It was brutal and terrible and you were shocked almost to insensibility to see the piles of dead and feel the hopelessness. One lad crouched six feet from me. He had made several attempts to rush down the ramp but each time a hail of fire had driven him back. He had been wounded in the arm but was determined to try again. He lunged forward, and a streak of tracer slashed through his stomach. I'll never forget his anguished cry as he collapsed on the bloody deck: "Christ, we gotta beat 'em, we gotta beat 'em!" He was dead in minutes.

I could see sandbagged German positions and a large house on top of the cliff. Most of the German machine-gun and rifle fire was coming from the fortified house and it wrought havoc. They were firing at us point blank. There was a smaller house on the right and Germans were there too.

The men from our boat ran into the terrible German fire and I doubt that any even reached the stone wall. Mortar bombs were smashing on the slope to take those not hit by machine-gun bullets that streaked across the tiny beaches. Now the Germans were turning their anti-aircraft guns on us. The bottom of the boat was covered with soldiers. An officer was hit in the head and sprawled over my legs. A naval rating had a gash in his throat and was dying.1

Of the 554 men in the Royal Regiment who landed at Dieppe that day, only 65 made it back to England. Photos of Puys Beach that include the fortified house that poured such murderous fire onto the beach, will be included in a future On This Spot tour focusing on Dieppe.

3. Dieppe's Defenses

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1213

1493

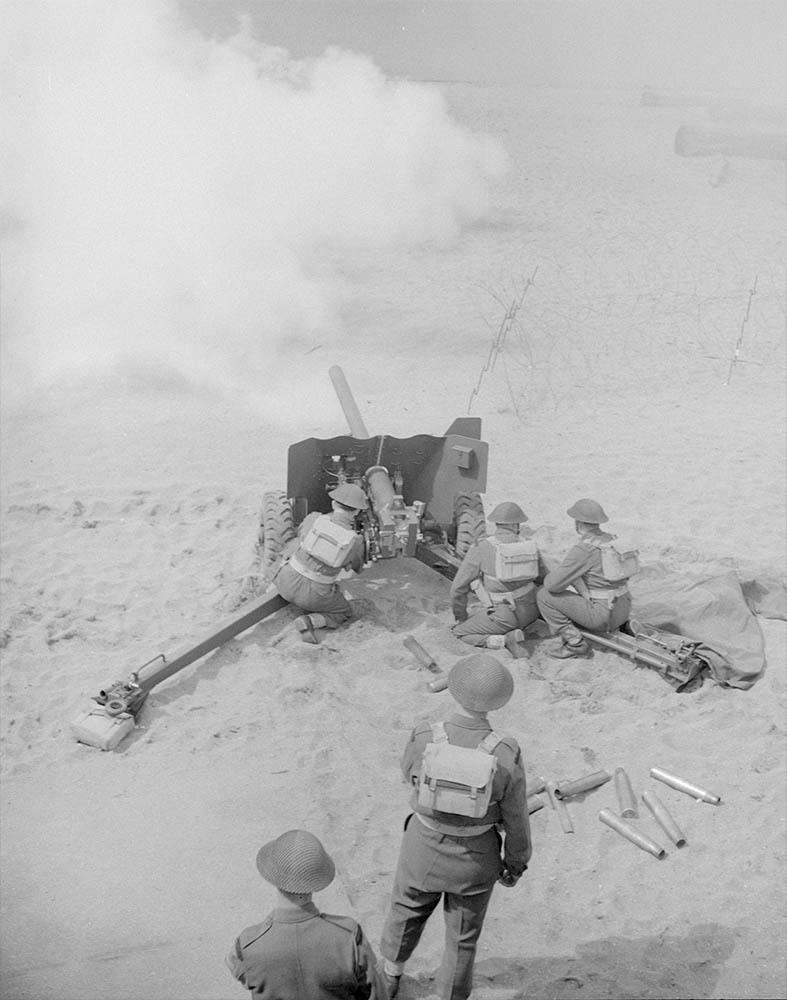

A 6-pounder anti-tank gun fires at the mock invasion fleet. The 6-pounder, which got its name from the weight of the shells it fired, was an effective weapon for stopping German tanks and a huge improvement over the 2-pounder that British and Canadian forces relied upon up to that point. This gun is sitting in the open on the beach, but the gun emplacements the Canadians faced at Dieppe were fiendishly more difficult to get at.

* * *

The Germans calculated that any Allied invasion would need to seize a port to allow them to off-load supplies. Unsurprisingly they set about fortifying Dieppe. Many historians believe Germany's Wehrmacht was one of the best armies in modern history, especially on the defensive.1 On the other hand the troops of the 2nd Canadian Division who took part in the raid had never seen action before.

In the hills overlooking the town a network of tunnels was dug and filled with machine-guns nests, anti-tank guns, mortars pits and snipers. They had a commanding view of the beaches while remaining practically invisible to their activities. Their weapons were pre-sighted on the expected landing grounds, usually positioned to provide lethal enfilade fire from the side. Buildings in the town were razed to give gunners clear fields of fire (Dieppe's French inhabitants were in no position to complain) and concrete pillboxes built on the ruins. Rows of barbed wire were strung across the broad esplanade in front of the town, ensuring any infantry running for the town would be fatally exposed as they looked for openings.

4. Breaching Dieppe's Defenses

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1225.2

1943

A battery of 3.7 Inch anti-aircraft guns fires as part of a demonstration. The inexperienced Canadian raiders at Dieppe bravely met the terrifying German defenses head on, but the sheer weight of fire pinned them down on the beach from the first moment. Only a few ad hoc groups of soldiers made it into the town.

* * *

Billy Field, a dispatch rider, remembered the cruel fate of the assault engineers who were weighed down with explosives as they ran for the seawall. The Germans picked them out and directed their fire towards them. "Each one went off like a bomb. I tried to keep my distance."1

Some intrepid soldiers worked their way forward, blowing a hole in the barbed wire above the seawall. With a battle cry 15 men ran into the town, slaughtering any Germans they encountered and engaging in frenzied room-to-room combat.

"Private A. W. Oldfield and three other soldiers started up a wide, circular staircase and met four Germans running down. The enemy turned in sudden flight. Grenades blew them to pieces. Oldfield found a sniper and went after him with his bayonet. For the first time in his life he killed a man while looking into his face, watching him die, trying to free the bayonet before he vomited over his victim's head."2

These small successes were not enough to dislodge the defenders. The main force and their tanks remained trapped in the death zone on the beach as waves of Canadian reinforcements were tragically ploughed into the unfolding disaster.

After some hours the inevitable was accepted and the order to retreat issued. The tanks, immobilized on the pebble beach, could do nothing but cover the infantry as they scurried back to the surviving landing craft. None of the tank crews made it off the beach.

5. Air Supremacy

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1225

1943

The seven man crew of a 3.7 inch anti-aircraft gun prepare to fire their weapon for a crowd of curious onlookers who can be seen in the background and to the right. Dominating the air during an amphibious operation was absolutely critical to the mission's success. At Dieppe the Allies failed to do this. D-Day two years later was a different story.

* * *

Most of the men on the beaches were too busy surviving to notice the titanic air battle going on above their heads. The pilots, for their part, were too busy with their own concerns to pay much heed to the battle below. In the end the Germans triumphed in the air as well, shooting down 111 Allied planes to a loss of 48.1

The lesson for the Allies was that complete domination of the air—air supremacy—was a crucial precondition for a successful invasion. The battle for command of the air on D-Day would not be decided in Normandy however, but in the skies over Germany.

After 1942 the Germans were forced to redeploy all their best pilots and planes to defend Germany from the fleets of British and American bombers that were methodically incinerating the Reich's cities. The Luftwaffe was built around a small cadre of elite pilots. In World War II the highest scoring American ace was Richard Bong, who was credited with downing 40 enemy aircraft. The Luftwaffe on the other hand had over 400 aces with higher scores, including over 100 pilots that had each shot down over 100 enemy aircraft. The highest scoring fighter pilot of all time was Erich Hartmann, who shot down 352 enemy aircraft.2

This huge disparity can be accounted for by the different approaches to elite pilots. The Germans tended to organize their best pilots into elite units and dispatch them to the most dangerous sectors of the front, sending them into battle again and again until they were killed. The Allies on the other hand withdrew their best pilots from battle and used them to train new pilots.

As a result, every German ace that was killed was a grievous blow to the Luftwaffe while the Allies could replace their pilots. As the outnumbered German aces rose to meet the fleets of bombers every day they exacted a hideous toll on the Allied air forces, but they were losing the war of attrition. By 1944 the Germans had barely any trained pilots left.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies could bring close to 9,500 combat aircraft to bear on Normandy. The Luftwaffe could muster a mere 570 aircraft in all of France, Belgium and the Netherlands.3

6. Juno Beach's Defenses

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S1-: CVA 1184-3496

1943

Troops rushing ashore in front of a 'pillbox', a little hut in the middle of the beach at left. A flotilla of sailboats just off the beach show the public are eager to watch these mock landings. In reality the German defenses encountered by the Canadians at Juno Beach on D-Day were infinitely more dangerous. 21,000 Canadians took part in D-Day. 340 of them were dead by nightfall.1

* * *

In the intervening years since Dieppe the Germans had refined their defensive systems too. Strung along the beach were numbered strongpoints each consisting of a network of infantry positions, armoured pillboxes, mortar pits, anti-tank bunkers and sniper nests. Often one anti-tank gun bunker would be covered by one or two machine-gun bunkers behind it, each of which would have their own supporting guns behind it. In this way any Allied soldiers who managed to crawl beside a bunker would be mowed down before they could hurl grenades into the embrasure.

Another difference from Dieppe was the land mines. The man who organized these defenses, Erwin Rommel, commanded six million land mines be laid up and down the coast of France. Many men from New Brunswick's North Shore Regiment stepped on these deathtraps as they sprinted across the beach on June 6. Partially submerged beach obstacles were strewn across the beach as well, designed to flip landing craft. Many were tipped with explosives. A number of boats from Toronto's Queen's Own Rifles were destroyed by these obstacles. The occupants, weighed down by 60 pounds of equipment, were dragged to the bottom.

While the horrific American experience at Omaha Beach is what springs to mind when most think of D-Day, the Canadians at Juno Beach also faced an extremely determined and well- entrenched enemy. A visit to Juno Beach today can't help but leave one in awe that the invasion had been possible at all.

7. The Bombardment

Vancouver Archives AM1184-S1-: CVA 1184-3592

1943

Small shells explode amongst the "bunkers" in a simulation of a naval bombardment. One of the bunkers, evidently made of timber and cloth, appears to be on fire already. The naval bombardment and logistical preparations for D-Day were absolutely mind-boggling in scope. Unlike Dieppe, nothing was left to chance by the Allied planners of D-Day.

* * *

The Allies were determined not to repeat the mistake at Normandy. Leonard Brockington was a CBC reporter aboard the Canadian destroyer Sioux on June 6, 1944. The Sioux's 27-year-old captain, Lieutenant-Commander Eric Boak, told him 'This operation cannot fail. It is the greatest organization this world has ever seen." He showed Brockington his orders for the pre-landing bombardment: "Printed documents two inches thick for one Canadian destroyer responsible for the bombardment of 200 yards of coast. If you multiply these instructions over the multitudes of operations, you will have some idea of the skill and thought British and American brains applied to this great exercise."1

Over 7,000 ships of every size and class took part in the D-Day landings. Assigned to Juno Beach were three cruisers, 11 destroyers and literally dozens of landing ships converted into gun platforms to support the landings. They carried rocket batteries, anti-tank guns and platoons of M7 Priest self-propelled guns that could fire from the pitching deck. Together they hammered the defenses for an hour and a half as the assault troops prepared to approach the beach, a symphony of explosive that stunned the defenders and shrouded the beach in smoke.2

Despite the bombardment most of the German defenses remained intact. One company of the Queen's Own Rifles was practically annihilated by fire from a strongpoint as they ran for the seawall. The deteriorating situation was only salvaged when one of the converted landing ships, bristling with heavy guns, came so close to shore it nearly ran aground and poured a terrific fire straight into the bunkers at point blank range.

8. Communications

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1216

1943

Some soldiers who look barely out of high school manage an awkward radio on the beach. In the event of an invasion these men would have practically the most important job on the beach.

* * *

The troops going over the top would lay telephone wires behind them which were promptly cut by artillery fire. The commanders were far behind the front lines and through the fog of war only scattered progress reports reached them by runners. The commanders would decide the attack was succeeding and command fresh waves of men forward, sending them like lambs to the slaughter without realizing the catastrophe unfolding in no man's land.1

By 1942 proper radios had been invented, but because most of them failed during the landing, essentially the same thing happened at Dieppe as the Somme. The 2nd Division's commander on a ship offshore received garbled radio messages that a foothold had been established in the town—in reality just those previously mentioned 15 men who made a mad dash past machine guns. Thinking that the raid was going well and it was time to consolidate these gains, he dispatched fresh regiments to the beach where they were slaughtered.2

9. The Tanks

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1214

1943

Soldiers and a Bren Gun Carrier dash ashore. The terror in the moments leading up to the landing are difficult to fathom. In his novel Home Made Banners, Ralph Allen, who took part in the landings, described the feelings of a soldier as his craft approached shore on D-Day. "The sweat lay on his face in pools, his fingers were stiff and leaden around his rifle. Beseechingly he looked across the boat. All he saw was each man's aloneness and, through it, his own. In a minute they would be pooling the unfathomable resources of their spirit in the only perfect community to man, the community of battle. But in these last moments each was on his own. There was nothing any man could do for his neighbour or for him. "1

* * *

The Quebecker Leo Gariepy lost 14 of the 18 DD Shermans in his troop while clearing the beach. One of the experiences he recorded is a tragic reminder of the madness of war.

"I was called by an infantry officer who told me a sniper had shot the commanders of three DD tanks. The sniper had not shot at the infantry; he was after tank commanders. I moved slowly toward where the other crew commanders had got hit, wrapped my beret over my earphones and waved it above the turret. The shot, when it came, was from an attic window, but the infantry were unaware of it and they were all round that house, making it impossible for me to fire into it. So I and my loader operator jumped out, hugging close against the wall, and bashed the door open. We found an old man and woman, imploring us in German, but we could not understand what they were trying to tell us. We rushed up the stairs and there in front of the attic window, holding a Mauser low but pointed at us, was the sniper, a girl of 19. I cut her down with the Sten. Angry, irritated, probably scared, I could not hesitate. We learned from the old people that this girl's 'fiance' had been shot by a Canadian tank that morning and she had sworn she would liquidate all crew commanders.2

10. Could You Do It?

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1224

1943

When reading of these great and terrible events you can't help but wonder do if you were put in the shoes of one of the participants. When the line between life and death is so fine and the odds of living out the day so dependent on random chance, what thoughts would be going through your head? How would you react? We can only hope we never have to find out.

* * *

Those last 200 yards were bad. The German fire was getting the range of our boats. I had a dry, hot feeling in my throat. I wanted to be doing something—not just sitting in that damned boat.

The second the boat scraped the beach I Jumped out and started to follow the sappers through the barbed wire. My immediate objective was a concrete pillbox on top of a 12-foot parapet about 100 yards up the beach.

I think I had taken three steps when the first one hit me. You say a bullet or a piece of shrapnel hits you but the word isn't right. They slam you the way a sledgehammer slams you. There's no sharp pain at first. It jars you so much you're not sure exactly where you've been hit—or what with.

The piece of shrapnel hit me in the right shoulder and knocked me down. I felt confused and shaken up, the same feeling you get on the football field after getting tackled from behind. Stunned, surprised, frustrated.

One of my men came up and I yelled "Go on! I'm all right!" I don't know why because I didn't know how I was.

I got to my feet, and brought my left hand around and felt my right shoulder. It was damp and sticky. I looked at my hand at it was covered with blood, I was bleeding badly.

I reached for my first-aid kit. I fumbled with it and then thought, "How the hell can I bandage my shoulder with my left hand?"

All this time I was I was standing practically upright on a flat stretch of beach raked with fire. The second that shrapnel hit me it seemed to shut out everything else. My only thought was whether I was in one piece. But reaching for my first-aid kit seemed to bring everything back into focus.

I think it was then that discipline and training came in. The natural instinct of any untrained man would have been to dig a hole, crawl in and stay there with his eyes shut. But discipline and training proved strong enough to keep me going. I saw the pillbox was still holding out, and I began flanking it with a group of men.

The second one soon got me. There was pain with this one because the shrapnel burned through the cheek and tore away quite a bit of flesh. I brought my left hand around again and felt my cheek. It's funny the way you instinctively try to feel where you've been hit. The cheek felt raw, as though someone had ripped a fish hook through it.

I crouched low and kept moving. We had covered about 25 yards when a man crumpled in front of me. He was a major, one of my closest friends. He was holding his stomach, a bad place to be hit because nothing outside of a hospital operating room could help him. His face was gray and he was sucking hard for breath.

I began fumbling for my first-aid kit again. My friend was watching me, but didn't say anything. I got out some morphine tablets, put one on his tongue and he swallowed it. There was nothing else I could do. He knew it and I knew it.

I went on toward the pillbox. Up to that point, I'd been more or less brave, let's say, because of discipline and training. I hadn't felt any particular anger because of my own wounds, but now, with my friend lying there, I was so blind angry that it seemed to push everything else out of my head. All I wanted was to kill, to get even.

I had to direct my unit, so I had to control this rage. But it seemed to clear my head, to make me think harder and faster. It also seemed to act as a sort of general anesthetic. Trying to get up over the parapet, I was hit again—this time by a bullet. It knocked me backwards onto a steel picket, seriously injuring my spine. The bullet went clean through my right arm above the wrist and smashed two bones. I barely felt it. And yet, under ordinary circumstances I'll bet a man would pass out if a heavy-caliber bullet smacked into his arm like that.

My rage pulled me along to the pillbox and I found that our men had cleaned it out. From here I could get a good idea of what was going on and direct the attack by field wireless.

Within the hour we got our part of the beach fairly well under control. But there were plenty of snipers and lots of mortar and shellfire. Shrapnel got me again when I tried to improve my position and get to higher ground. This time it was my right leg above the knee. It had the same sledgehammer effect as the first, but I managed to stay on my feet.

Our men were filtering into the town and some of our tanks were on the promenade. I wanted desperately to get in there too. But I could feel myself slipping, getting weak.

I fell, tried to get up again, but couldn't. My whole right side felt warm and soggy. Then the pain began to come and I started praying, harder and harder. And then I passed out.1

Endnotes

- 1. Bannerman, 6.

1. The Situation in 1943

1. Churchill Society.

2. Canadian War Museum.

3. Canadian Forces.

2. Worst Case Scenario

1. Reader's Digest, 181.

3. Dieppe's Defenses

1. Hastings, 12.

4. Breaching Dieppe's Defenses

1. Reader's Digest, 208.

2. Reader's Digest, 189.

5. Air Supremacy

1. Zuehlke, 352.

2. Whitmarsh, 57.

3. Wikipedia.

6. Juno Beach's Defenses

1. Reader's Digest, 450.

7. The Bombardment

1. Reader's Digest, 435.

2. Whitmarsh, 72.

8. Communications

1. Keegan, 180.

2. Reader's Digest, 200.

9. The Tanks

1. Reader's Digest, 435.

2. Reader's Digest, 445.

10. Could You Do It?

1. Reader's Digest, 197.

Bibliography

"About the Army." Canadian Forces. Last Updated 13 July, 2016.

Bannerman, Gary. Gastown: The 107 years. 1974.

Hastings, Max. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. London: Vintage Publishing, 2006.

Keegan, John. The First World War. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2000.

"List of World War II Flying Aces." Wikipedia.

Reader's Digest. The Canadians at War 1939-1945. Toronto: Reader's Digest, 1969.

"The End of the Beginning." 10 November 1942. Churchill Society website.

"The War Against Japan." Canadian War Museum. Website.

Whitmarsh, Andrew. D-Day in Photographs. New York: Stroud History Press, 2009.

Zuehlke, Mark. Tragedy at Dieppe. Toronto: Douglas and McIntyre, 2012.