Walking Tour

Architecture

A Tale Told in Wood, Brick and Steel

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-3895

For most of us, our buildings are utilitarian things, little more than pieces of scenery. They are to be lived in and worked in, but rarely considered and appreciated. Walking down the street we may be struck by a particularly handsome or interesting building, but the moment is fleeting and quickly lost in the hustle and bustle of daily life.

Yet that momentary spark of inspiration is in some ways the essence of architecture. Canada's most legendary architect, Vancouver's own Arthur Erickson, said, "Whenever we witness art in a building, we are aware of an energy contained by it."1 Careful, considered and conscious effort has been put into every aspect of the way we interact with our buildings. They are designed to impress and to inspire. To make us feel.

One of the most wonderful things about living in a city is being surrounded by fine examples of architecture. Taking the time to contemplate that architecture can be an immensely enriching experience, opening the door to a deeper understanding of the people that created it. A city's buildings are a reflection of a society's values and the way it sees itself.

As the Oxford History of Architecture put it, "Architecture, to state the obvious, is a social act—social both in method and purpose. It is the outcome of teamwork; and it is there to be made use of by groups of people, groups as small as the family or as large as an entire nation. Architecture is a costly act. It engages specialized talent, appropriate technology, handsome funds. Because this is so, the history of architecture partakes, in a basic way, of the study of the social, economic, and technological systems of human history.”2

This tour will guide you through the rich architectural legacy of the first 50 years of Vancouver. We will see who and what inspired Vancouver's most famous landmarks. We will learn the characteristics of some of the most prominent building style and examine the social, economic and technological changes reflected in the buildings from this dynamic and exciting time.

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

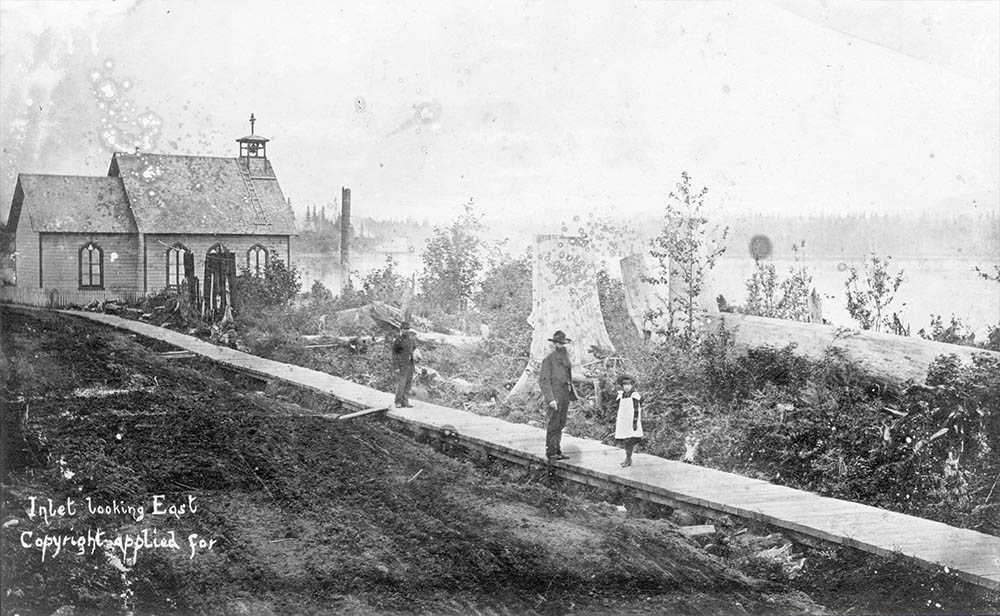

1. St. James Church

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Ch P15

1885

This photo gives an early idea of the frontier-town atmosphere that prevailed in Vancouver before it was called Vancouver. A small, wooden St. James Church is fronted by an impossibly muddy road navigable only with the help of duck-boards. The scrappy town's ramshackle structures represented a hard-won foothold in a vast and unforgiving wilderness.

* * *

The city's first residents had an infinite supply of cedar and fir close to hand, so they built most everything out of wood. Their buildings were squat, one or two-storey affairs, fronting Vancouver's several muddy streets. As these structures could be thrown together in a matter of weeks or even days (according to the legend Gassy Jack's bar was built in a day), it lent the whole city a temporary feel. Yet many of first inhabitants, Gassy Jack foremost amongst them, were hopelessly optimistic about the settlement's prospects and believed one day it would take its place amongst the world's great cities. For an observer surveying the mud, tree stumps, and shacks that constituted Vancouver in 1886, that dream must have seemed an impossibly distant mirage.

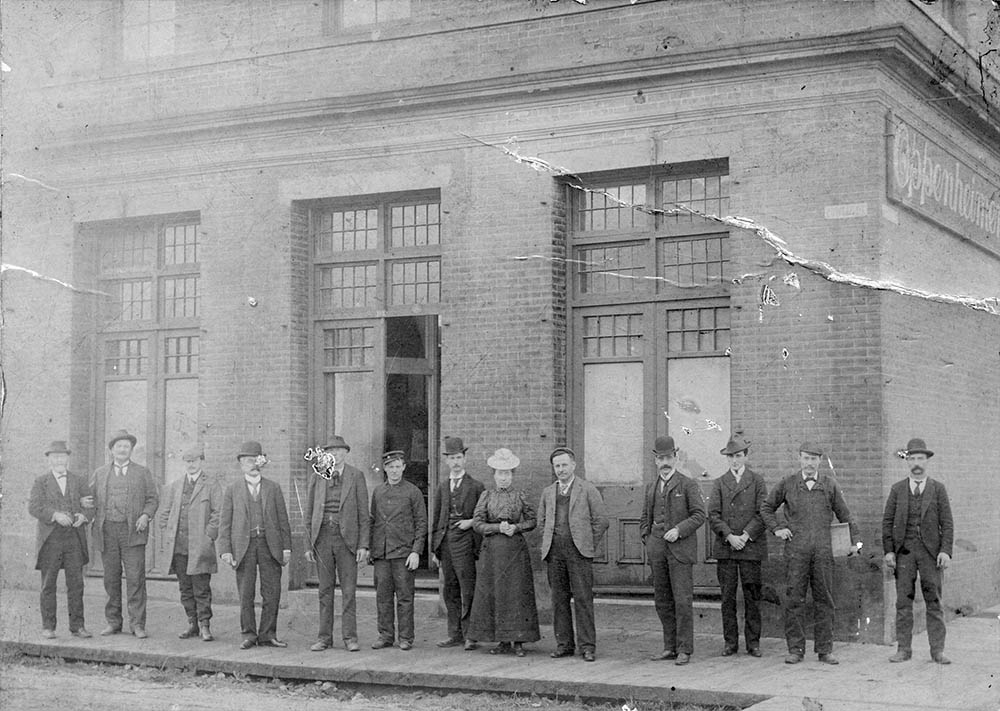

2. Oppenheimer Building

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P683

1898

The first step to becoming a great city was to become a city in the first place, and this was accomplished to much fanfare in April 1886 when Vancouver incorporated. Two months later on June 13, almost the entire city burned to the ground; a most inauspicious start. One of the few buildings to survive was the one you see here, the Oppenheimer Building, which was still under construction at the time. It was the only brick building in the city.

* * *

With a booming economy, an expanding population and the arrival of talented architects from Great Britain and the United States, a new city rose from the ashes of the old with extraordinary speed. Many of the buildings in Gastown today date from this huge burst of energy that followed the fire. Within a year there were 57 buildings on Cordova Street, 39 on Water Street and 26 on Carrall. In 1887 alone over $1.5 million was built on new construction.2

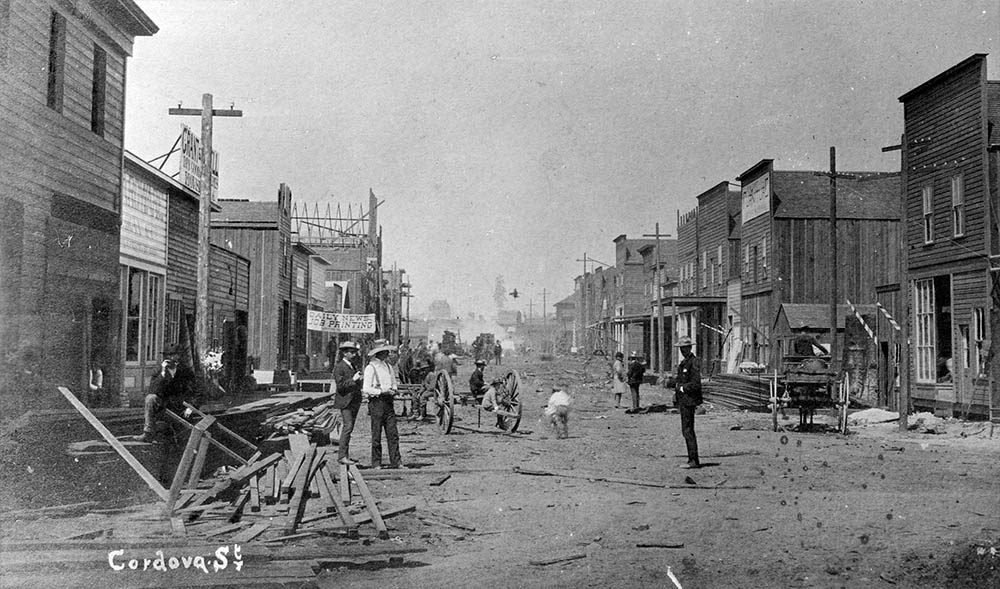

3. Byrnes Block

Vancouver Archives AM336-S3-3-: CVA 677-577

1907

Almost immediately after the fire the city became gripped with railway fever as the Canadian Pacific Railway drew near. The city's merchants sought to lure new customers with new and exciting buildings designed in a whole range of architectural styles. By far the most popular was the Renaissance-derived Italianate style seen here in the Byrnes Block. It's the building on the left.

* * *

One of the very first was the Byrnes Block, built on top of the smouldering ashes of Deighton House, the successor to Gassy Jack's old tavern. Fittingly located at the symbolic heart of Vancouver, this building set a new standard for the city's merchants to aspire to. Housing the Alhambra Hotel, it was designed in the Italianate style, the British Victorians take on Italian villas from the 1500s. There are a number of noticeable Italianate features like the flat roof, the tall, narrow windows with ornamental mouldings at the top and a projecting strip along the top of the building called a cornice that was held up by decorative brackets. This style became hugely popular in Vancouver in the 1880s and you'll notice many Italianate buildings when you're walking around Gastown.

The beautiful exterior was matched by an opulent interior that itself set a new standard in luxury accommodation. No longer would Vancouver be a place where people who died in bars be left to rot on the floor!

4. The Last Best West

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P7.1

1886

This photo was taken just five weeks after the great fire, in July 1886. If you zoom in on the man in the black coat just right of centre, you may notice he bears a striking similarity to the antagonist in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Admittedly all the buildings are not made of brick yet, but they would soon be replaced with ones of more sturdy construction.

* * *

This was largely thanks to the outward-looking and open-minded views of British architects in the late 1800s. Today architecture is viewed as a technical profession, but back then it was seen as more of an art. Like any good artists, 19th Century architects went out looking for inspiration. For British architects this meant scouring Europe for ideas and they had over 2,500 years worth of building styles to choose from.

Soon practically every conceivable architectural form that could be seen in Europe was 'revived', with each architect adding a few touches of their own. To name a few, neo-classical buildings looked to ancient Greek and Roman temples, Romanesque Revival buildings were inspired by early-Medieval abbeys , and the Baroque style of Britain's 18th Century was dusted off and updated.

A handful of these architects came to Vancouver, bringing with them an intellectual legacy that spanned the many nations of Europe and extended back in time for millennia. In Vancouver they had pretty much a blank slate to work with.

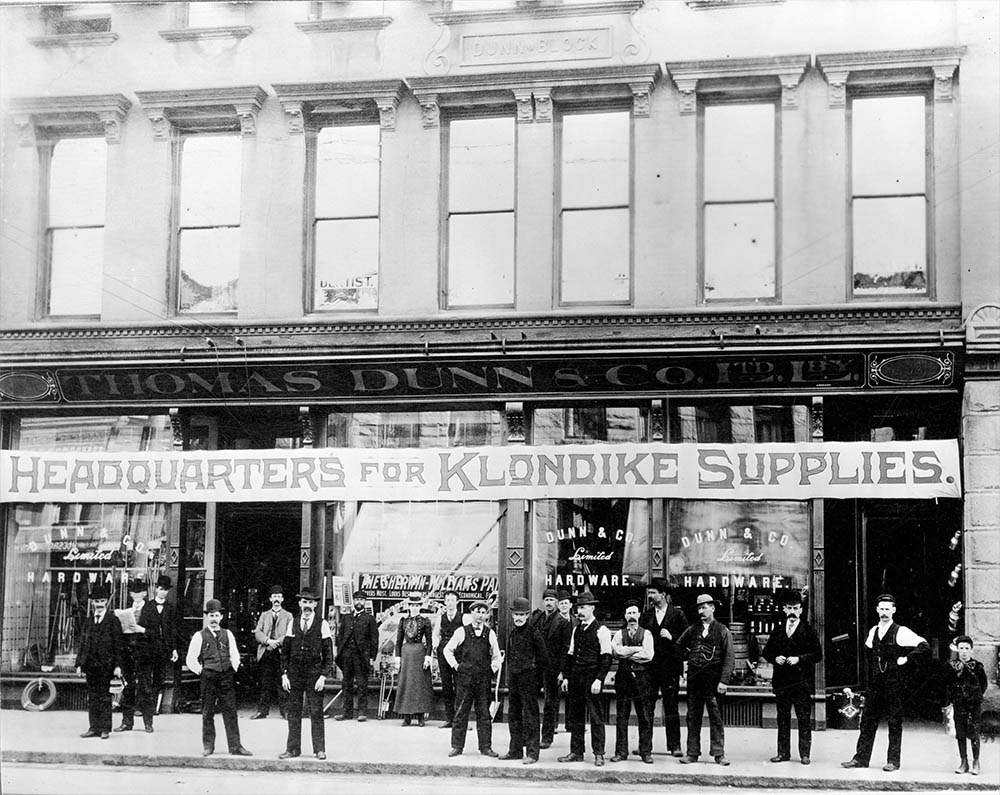

5. The Dunn-Miller Block

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P89

1898

According to the archivist Major J.S. Matthews, the Dunn-Miller Block you see here was "at the time it was built, in 1889, the largest, most pretentious, and important building in Vancouver."1 An example of the Italianate style, it was just the biggest of a great many commercial blocks that combined ground-level storefronts with upper-floor housing and offices.

* * *

Like all of Vancouver's economic booms, the first one, fueled by the railway and post-fire reconstruction, did not last. In 1893 a panic sell-off on Wall Street sent shockwaves around the world. This was followed by a rock slide in the Fraser Canyon that devastated the salmon run and walloped the province's fishing dependent economy. The province went into a deep recession and the building boom ground to a halt. By 1896 half of the city's carpenters were out of work.2

Then another boom came in 1898 (the start of a Vancouver pattern) when gold was discovered in the Klondike. Tens of thousands of American gold prospectors stopped in Vancouver to stock up on supplies for the arduous journey to the Yukon. As you can see the Thomas-Dunn hardware store made every effort to capitalize on this new source of revenue. Almost overnight all the builders were back in business.

6. Woods Hotel

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-3895

1931

This peculiar building was known as the Woods Hotel when it was completed in 1906. It billed itself as the "only modern" hotel in Vancouver, 1catered to the wealthy.8 Hotels at this time were much more common, and they ran the gamut from posh, luxurious suites like the Woods Hotel to squalid, run-down rooming houses for the seasonal workers who needed a place to stay in the off-season. Hoteliers who could afford architectural flourish used it to great effect in standing out from the competition.

* * *

The architect was the talented William Whiteway, who, as we will soon see, can be credited with many of the city's most beautiful landmarks. He drew inspiration from his time in California in the 1880s and gave the building a distinctly San Francisco-feel: notice the many bay windows and the way they are prominently divided into sections, as well as the curious turret. If you walk inside through the entranceway, the round arch and strong masonry foundations are unmistakable Romanesque Revival elements. Romanesque is a style derived from early medieval abbeys across Western Europe. Those abbeys were themselves a revival of later Roman architecture. He certainly had a talent for mixing and mashing different styles.

7. Holden Building

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-1---: M-11-33

1910

William Whiteway next went on to design the Holden Building, which you can see going up behind the Woods Hotel in this picture. As the city grew and developed, buildings like this filled the growing and rather novel need for office space. It bears some reminding that in pioneer-era Vancouver there were few white collar jobs and not much need for space for them to work. As the city grew and industrialized all sorts of new occupations sprang into existence. This particular building housed trade unions headquarters, political parties and for a time, Vancouver's city council while the new city hall was being built.

* * *

The building's owner William Holden was an extremely successful real estate agent and investment broker and has been dubbed "the man who built Granville Street."1 It's a bit ironic then that when he had this skyscraper constructed here the city's centre of activity was moving from Hastings to Granville Street. Shortly after the Holden Building was completed in 1911 the real estate market collapsed and the Hastings strip was never to recover. Too bad he didn't build it on Granville.

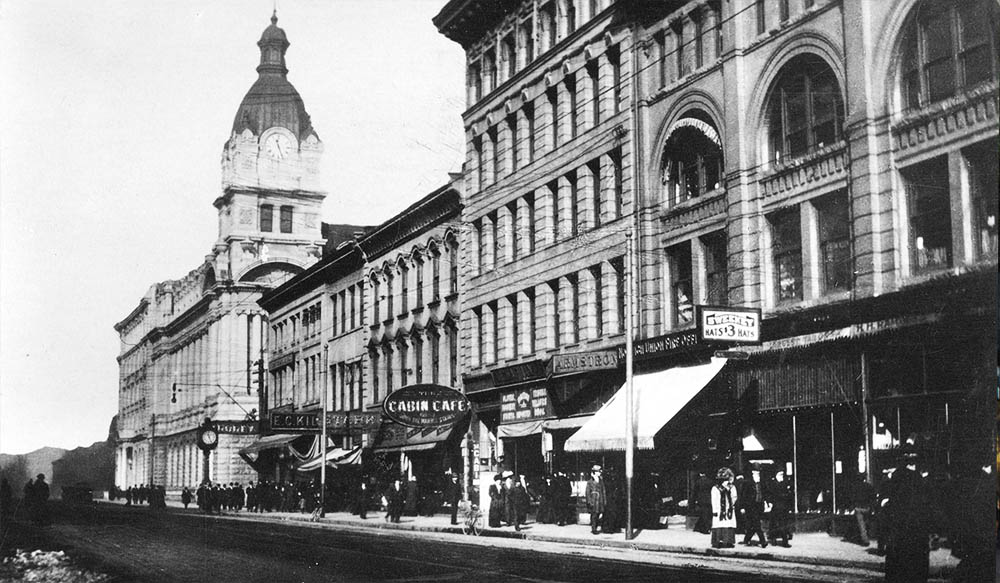

8. Hastings Great White Way

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: LGN 1017

1914

The Rex Theatre is visible on the left in this view east down Hastings Street. The Theatre is now the Army and Navy Store, but at the time it was but one of a host of glitzy and opulent vaudeville theatres, purpose-built for entertaining the masses. So many were on this it was nicknamed "The Hastings Great White Way," imitating the nickname for Broadway in New York.1

* * *

The major vaudeville theatre chains were not too concerned about the rise of "photoplays", convinced they were just a fad. Unfortunately for them, they were not. By the late 1940s most of the vaudeville chains had been run out of business by the movie industry. Most of the city's once popular vaudeville theatres, like the Lyric, the Strand, and the Majestic, have been demolished.

9. World Tower

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1274

1918

A crowd has gathered to watch Harry Gardiner, a stunt man called "The Human Fly", climb the World Tower as part of a war bond rally. Completed in 1912, the World Tower (the Sun Tower since 1937) was a triumph of engineering and ambition. It signalled to the world that Vancouver's transition from back-woods logging town to world-class metropolis was well underway.

* * *

The World Tower was built to house the Vancouver World, a newspaper bought out by the Vancouver Sun in 1924, hence the name change. At 17 storeys it was in fact the biggest building in the British Empire when it was completed, stealing the title from the Dominion Building located just a block away. At the time the British Empire ruled over a quarter of the world, so this was no idle boast.

Skyscrapers were the ultimate symbols of modernity, optimism and economic success. Builders in cities like New York and Chicago fiercely competed to erect the world's tallest skyscrapers, just as places like Dubai, Shanghai and Guangzhou are vying for the same honour today. And for a brief moment a century ago Vancouver neared the top of the leaderboard.

10. Steel-Framed Construction

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Trans P149.12

1909

Here is the Dominion Building under construction. A beautiful building, it was the tallest in the British Empire until the World Tower, which we just saw, topped it. It is difficult to overstate the impact skyscrapers had on people when they first saw them. For millennia buildings had been limited to about ten storeys in height, but a confluence of industrial age technological advancements developed in Chicago after that city burned down suddenly made it possible to build into the third dimension. In those heady days anything seemed possible.

* * *

This was all made possible by the steel-frame skeleton you see above, and the use of proper building foundations. Before steel-frames the walls of buildings had to bear all the weight of the floors above. Every extra floor put greater stress on the walls, limiting building heights. On the other hand, steel frames had an almost limitless capacity to hold weight, and the walls could be tacked on almost as an afterthought—hence the architectural term 'curtain-walls'. Modern building foundations were also first tried out in Chicago's swampy downtown as that city rebuilt after its own Great Fire in 1871. Finally the near simultaneous invention of the elevator made it feasible to live and work at such heights.

11. Dominion Tower

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 8-06

1912

The owners of skyscrapers are uniquely vulnerable to economic swings, and it was unfortunate for the owner of the Dominion Building that the bottom fell out of the economy only four years after the grand building was completed. The Dominion Trust Company collapsed and the vice-president blew his own head off with a shotgun.1 It was not considered a lucky building—on the building's opening night the architect also allegedly fell down the stairs and died.2

* * *

One of the obvious benefits of tall buildings was that they unlocked space, allowing more people to be crammed into a smaller area. Geography certainly played a role in Vancouver's early forays into skyscraper-building: Vancouver, like Manhattan, is on a peninsula and space has always been at a premium.

Yet with the benefits also came drawbacks. Skyscrapers are extremely high-risk investments. When you finish a skyscraper you are effectively dumping tens of thousands of square feet of office space on the market at once. If the economy takes a nosedive then nobody is going to pay to rent that space.

This is exactly what happened after the Dominion Trust Building was completed. From 1908 to 1913 the value of land in Vancouver quadrupled in the midst of a ludicrously out-of-control real estate bubble. When the bubble popped in 1913, the Dominion Trust Company went under, the first of a series of cascading bank failures. Vancouver fell into an economic tail spin that would take decades to recover from. All of this might give us pause for thought today.

12. Old Post Office

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P162

1914

The clock tower on the building ahead is an impressive example of Baroque Revival style, briefly popular around the turn of the last century. It was an expression of imperial optimism and a reflection of the power of the state. The building the clock is mounted on was once Vancouver's post office.

* * *

Completed in 1892, Vancouver's first post office was a three storey stone building located a couple blocks up Granville. At the time it was one of the city's most prominent buildings, but Vancouver's meteoric growth quickly meant a bigger building was needed. Meteoric isn't a strong enough word. Vancouver's population exploded from 22,000 in 1891 to 164,000 in 1911, a mind-boggling increase of 750% in just 20 years. To put that in perspective, from 1991 to 2011 the population grew by a measly 70%.1

A grand new building would be needed to show the city's many new inhabitants that the federal government was here and in control. The post office you see in front of you was the result.

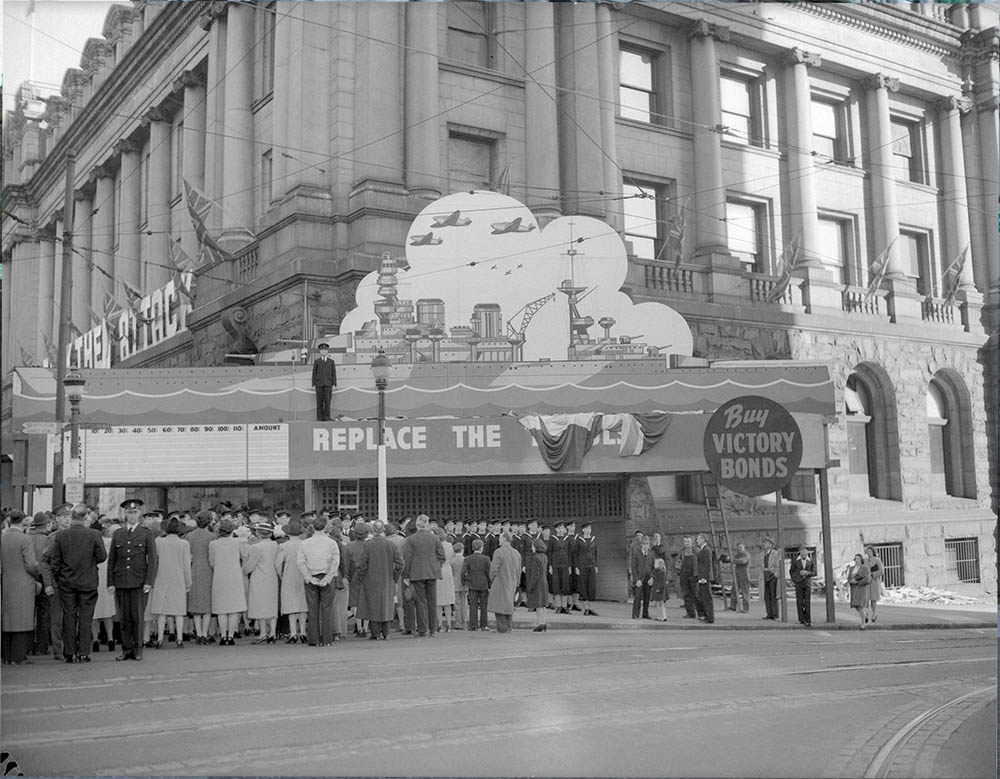

13. Replace the Repulse

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-1193

1943

This war bond drive to fund the replacement of HMS Repulse, a British battleship sunk in 1941 by Japanese bombers, was held in front of the new post office. The building was completed in 1910 and it's no coincidence it bears more than a passing resemblance to the War Office in London. This architectural style harkens back to Canada's embrace of the Mother Country and the British Empire, a time when most Canadians saw themselves as much—If not more—subjects of London than of Ottawa.

* * *

While conveying the success and unity of the empire, the Baroque Revival style also reflected the boundless optimism of a time when European imperial powers held sway over practically the entire world. With this building the people of Vancouver showed that even here, 7,500 kilometres from London, the bond with the mother country was as strong as ever.

14. Vancouver Block

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: SGN 1527

1912

The clock tower up ahead sits atop the Vancouver Block, a stunningly beautiful building commissioned by the brother of Patrick Burns, the fabulously wealthy meat-packing magnate nicknamed the "Klondike Cattle King". It's tall and unmistakable silhouette continued to dominate the city's skyline for decades after it was completed in 1912. It firmly established Georgia and Granville as the city's commercial centre in the Edwardian era just before World War I.

* * *

Each face of the clock was 22 feet across, making it the biggest clock in Canada—Vancouver's own mini-Big Ben. The glass in the dials weighed over four tonnes. Within the tower a sumptuous penthouse suite was built for Burns, giving him expansive views across the city.

Though Burns' fortune managed to survive the economic catastrophe of 1913, very few others did. As a result the skyline of Vancouver remained frozen until the late 1920s, when companies could finally feel secure enough to invest in grand new buildings.

15. Hudson's Bay Company

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-1228

1920

Shop owners are being evicted to make way for the expansion of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) store. The store itself began as a small red-brick building on the corner of Granville and Georgia. In 1913 the style of building you see today was put at the corner of Granville and Seymour, and then expanded multiple times over the year so now it takes up much of the block. The photo above was taken before one of those expansions.

* * *

As Canada's oldest and most successful company, the HBC built department stores on this same pattern across all western Canada in the Edwardian period. The palace-like neo-classical design seen here was designed by the HBC's architects, Burke, Halwood, and White from Toronto. The design was so popular they imitated it across country, modeling stores in Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg and other cities after this one.

16. Third Hotel Vancouver

Vancouver Archives AM281-S8-: CVA 180-1631

1950

A parade to mark the opening day of the PNE carnival marches past the Hotel Vancouver and the court house (now art gallery). This iconic Hotel Vancouver was actually the third to bear the name, built by the CPR in a trademark Chateau style and meant to encourage cross-Canada railway tourism. As the railwayman Sir William Van Horne declared, "Since we can't export the scenery, we shall have to import the tourists."1

* * *

In the early 1900s, when Vancouver was playfully nicknamed "the city outgrowing its clothes", a bigger and better CPR hotel was needed and the result was the enormous and lavish second Hotel Vancouver.2 It was closed in 1939 and demolished a decade later, replaced by the third Hotel Vancouver, seen here. The CPR’s architect Bruce Price perfected this interesting style of architecture called Chateauesque, a revival of French chateaus built in that country’s southwest in the 17th Century. The defining characteristics were the steep roofs, asymmetrical layout, and advancing and receding planes of the facade, all abundantly in evidence here.

17. The Court House

Vancouver Archives AM1535-: CVA 99-3626

1935

Governor General Bessborough, a British businessman and politician, hands out medals at a ceremony in front of the court house. Today this is the art gallery. The court house, designed by legendary British Columbia architect Francis Rattenbury, was another example of official architecture meant to convey the power and wealth of the state.

* * *

The ambitious 25-year-old Rattenbury arrived in Victoria in 1892. It didn't take long for him to make an impact: The provincial government was accepting design proposals for the provincial legislature and Rattenbury immediately submitted a plan, along with 60 other more experienced architects. In a shock move, the province selected the young Rattenbury's Romanesque Revival plan that, it was felt, perfectly encapsulated the medieval roots of parliamentary democracy.

His Empress Hotel and CPR Steamship Terminal are also lynchpins of Victoria's Inner Harbour, and it is these designs that cemented his legacy. His rapid rise to fame over the heads of many more experienced architects can be attributed, according to the architectural historian Donald Luxton, to his ability to capture the imperialist mood of British Columbia at the time.1

18. Francis Rattenbury

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-884

1920

We can see the court house at right and the second Hotel Vancouver at right. Rattenbury's court house gave the city centre a sober gravitas and stability, but these attributes were not reflected in his scandal-filled life. Today Rattenbury is known less for the fantastic buildings he designed than for the sensational way he died.

* * *

In 1898 he married Florence Nunn and as the years wore on and a number of his financial ventures failed, the relationship became strained. It didn't help that his style of imperial architecture went out of style. By the 1920s Florence and Francis weren't even on speaking terms, and their daughter had to pass notes between them. Setting his wife aside (though not divorcing her), Francis fell in love with Alma Clarke Dolling Pakenham, a war widow 30 years his junior. The scandal this caused in high society did irreparable damage to his reputation. To escape the whispers of the chattering classes he formally divorced his wife and then took moved with Ms. Pakenham to England in the early 1930s.

Once in England Rattenbury hired a 17-year-old to be his chauffeur. His new wife promptly seduced the chauffeur and they began a passionate affair. Over the following months the chauffeur became convinced Rattenbury was on the verge of discovering them. Consumed by paranoia, he snuck up on the legendary architect and bludgeoned him to death. Rattenbury was 68. The trial that followed was one of the most sensational of the 20th Century, attracting an exceptional amount of coverage in the British tabloids.

19. The Marine Building

Vancouver Archives AM1545-S3-: CVA 586-4466

1946

After the economic slump in 1913 it was over a decade until the economy began a tepid recovery. By the roaring '20s, some companies were again willing to take the risk of building new skyscrapers. The most famous is the one at left further down Burrard. The Marine Building remains one of North America's most cherished examples of the Art Deco style that briefly flourished in the 1920s and 1930s. Poet laureate Sir John Betjeman called it "the best Art Deco office building in the world."1

* * *

The building was commissioned by a shipping company who paid enormous sums for intricate decorations tying the building to a maritime theme. The entrances and walls were inlaid with blue and gold mermaids, sea snails, crabs and scallops while transportation motifs like trains and ships proliferated as well. The idea, according to the architects McCarter and Nairne, was to evoke "some great crag rising from the sea, clinging with sea flora and fauna, tinted in sea-green, touched with gold."2

20. Modernism

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Trans P112

1945

The Marine Building was completed in 1930, right at the outset of the Great Depression. Once again all building ground to a halt as capital dried up and the unemployment rate soared. By the time the economy rebounded after the Second World War modernism, a new school of architecture that recast the architect as an technician and social scientist instead of an artist. The beautiful buildings of Vancouver's early years gave way to simple, utilitarian structures of concrete and glass. Art Deco was the last hurrah of the old style of architecture.

* * *

Modernism started in the suburbs. Utopian philosophy aside, modernism's adoption was sped up by the need for tremendous amounts of cheap housing after the Second World War. The housing of Canadians had been allowed to decay through decades of neglect, and in 1945 a shocking 61% of homes had running water. Only half had a toilet. At the time this was considered a disgrace.2 Today, it is completely unimaginable. Modernist designs, which were cheap and easy to build, provided the best method to bridge this gap. After modernism became normalized in the newly expanding suburbs it was only a matter of time before it would begin to colonize urban centres, resulting in the great majority of the buildings you see around you now.

As we will see in the Vanished Buildings tour, many of Vancouver's finest old buildings have not survived to the present. In the mania for science-based social progress that followed the Second World War, the great architectural legacy of early Vancouver was severely reduced and many beautiful old buildings torn down. It is only in recent years that we have come to realize the immense value of this legacy, and the importance of preserving it for the future.

Endnotes

- 1. Stouck, 69.

- 2. Kostof, 7.

1. St. James Church

1. Luxton.

2. Oppenheimer Building

1. Smith.

2. Cruikshank.

5. The Dunn-Miller Block

1. Luxton.

2. Luxton, 102.

6. Woods Hotel

1. Victoria Daily Colonist, 16.

7. Holden Building

2. Canada's Historic Places.

8. Hastings Great White Way

1. B.C. Entertainment Hall of Fame.

10. Steel-Framed Construction

1. Burns.

11. Dominion Tower

1. Lazarus.

2. Ghosts of Vancouver.

12. Old Post Office

1. Government of Canada.

16. Third Hotel Vancouver

1. Luxton, 101.

2. Luxton, 255.

17. The Court House

1. Luxton.

19. The Marine Building

1. A View on Cities.

2. Luxton.

20. Modernism

1. Liscombe, 30.

2. Luxton.

Bibliography

A View on Cities." "Marine Building." Online..

"Attractive Values in Preliminary Easter Offerings." Victoria Daily Colonist. 15 March 1907. Online.

B.C. Entertainment Hall of Fame. "The Hastings Great White Way."7 Apr. 2015. Online.

Burns, Ric. "Episode Three: Sunshine and Shadow." New York: A Documentary Film. New York: Steeplechase Films, 1999.

Canada's Historic Places. "Holden Building." 14 January 2003. Online.

Cruikshank, Julie. From Settlement to City: Vancouver's Growth to 1913. Vancouver, 1971.

Ghosts of Vancouver. "Haunted Locations: Dominion Building." Online.

Government of Canada. "1891 Census," "1911 Census," "1991 Census," & "2011 Census." Online.

Lazarus, Eve. "The Dominion Building." Every Place has a Story. 25 Mar. 2012. Online

Liscombe, Rodhri W. The New Spirit: Modern Architecture in Vancouver 1938-63. Toronto: Centre for Canadian Architecture, 1997.

Luxton, Donald. Building the West: The Early Architects of British Columbia. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2007.