Partner City

Toronto

Canada's Metropolis

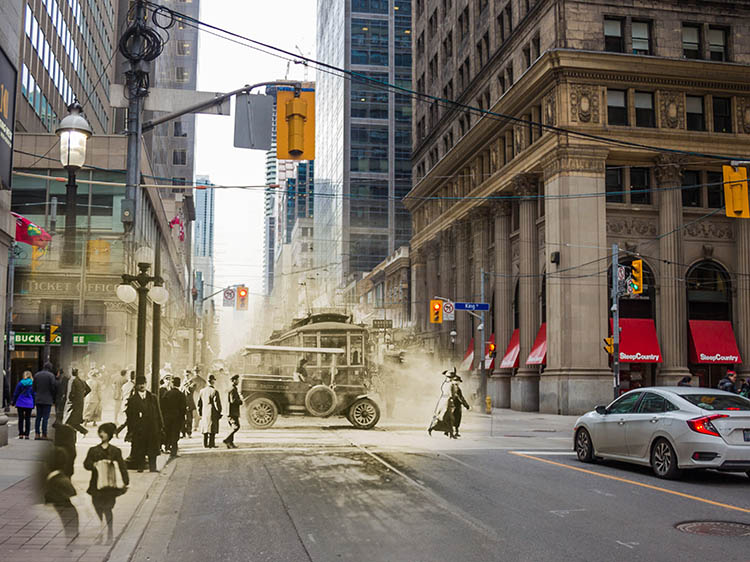

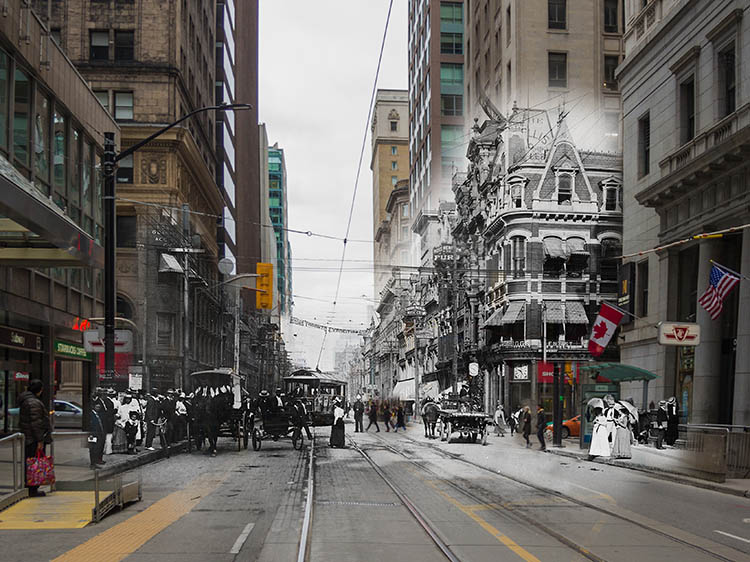

Canada's largest city and the capital of its most populous province. Toronto has gone through many phases in its modern history, from Muddy York, to Victorian era Toronto the Good, and finally world-class multicultural metropolis.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

We respectfully acknowledge that Toronto is on the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, Métis, and the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation.

Virtual Tours

Tours

Beyond Chinatown

Toronto's Chinese Community

Toronto's First Steps

The People and Ideas that Shaped Toronto's First Century

University Driveway to Little Italy

The History of College Street

Fear, Hate, and Xenophobia

Toronto's Stanley Barracks

Inside the Toronto Railway Museum

Museum Audio Guide

Outdoor Exhibits of the Toronto Railway Museum

Museum Audio Guide

Explore

Toronto

Stories

The Belt Line Trail

Toronto Railway Story

This image shows Moore Park Station in 1909. It was located on this spot along what's today known as the Kay Gardner Beltline Trail, a popular walking and biking path that passes through nine kilometres of some of Toronto's most scenic neighbourhoods. The trail is broken into three separate sections that run through areas such as Rosedale, Forest Hill and Moore Park, with opportunities to explore Mt. Pleasant Cemetery and the naturally restored Don Valley Brick Works Park. The trail follows the century-old route of the former Toronto Belt Line, a railway line that was meant to encourage the construction of suburban neighbourhoods further out of downtown.

* * *

In 1889, a group of businessmen founded the Toronto Belt Land Corporation to develop large parcels of land on the outskirts of the city. They envisioned a large boom that would swiftly cause these areas to grow into bustling suburbs. As these areas to the north and west of the city were out of range of the city's streetcar lines, they formulated a plan for a railway to connect them to downtown Toronto.

While the railway was initially proposed as a simple connector, it soon evolved into two separate loops of track, one north, the other west. The north track circled through the Don Valley and Mt. Pleasant Cemetery before linking up with the Grand Trunk Railway tracks near where Caledonia Road is today. The western Humber Loop followed Grand Trunk tracks west out of Union Station as far as Swansea, where it turned north through Parkdale before circling back around to return to Union Station.

Construction began on the rail in 1890, only about a year after the company's founding. While the early years of construction were fuelled by optimism, the anticipated land boom was halted by a depression midway through the railway's construction. The demand for suburban real estate crashed along with the company's fortunes. The Toronto Belt Line Corporation went bankrupt in early 1892, leaving the project to be completed by the Grand Trunk Railway with a final bill of $462,000 or roughly $11,750,200 today.1 While a project such as this was inevitably going to be expensive, the bill was inflated by lavish promotional expenses incurred by the Toronto Belt Line Corporation.2

One brochure marketing the new railway extolled the virtues of the lands that would be made accessible by the line, "... the Toronto Belt Line Railway makes its advent. Its mission is to economize time by rapid transit, and to carry men, women and children with comfort, safety and speed beyond the cramped and crowded city to the airy uplands; whence, having enjoyed the rest and refreshment of commodious homes and spacious grounds, they can return on the morrow to renew, with quickened energies, the task of life. It will also disclose some of the beauties which nature has lavished around Toronto which too long have remained unknown...”3

The first train on the new line left Union station at 2:40 pm on June 30, 1892. The locomotive pulled three passenger cars, each filled with seats made of cane and polished wood. According to the Globe, the cars were "perhaps the prettiest and brightest to be found on any [rail] road running into the city."4

For the first few months, the new line was very busy. "Each train is filled with hundreds availing themselves of the opportunity to inspect the much talked of route."5 However, the excitement soon wore off, and the ridership dwindled. After only two years, service on the line decreased from six cars a day, to only three, before closing completely in November 1894.

The decline of the Toronto Belt Line was due, in part, to the depression and the unrealised land boom. However, the fare was around 25 cents ($5.00 today) depending on the length of ride, which was considerably higher than the fare charged by the city's streetcars.6 This was too much for most people for a daily service.

Years after service on the Belt Line ended, Toronto's economy recovered and construction began on the subdivisions the Toronto Belt Line Corporation dreamed of decades earlier. These new neighbourhoods required fuel and building supplies as they grew and people moved in. In 1910, the Grand Trunk Railway rebuilt the northern portion of the Yonge St. loop so trains could freight materials to the new suburbs. Some tracks remained in the abandoned parts of the route until World War I, when they were deconstructed and shipped to France as part of the war effort.

Trains continued to run along parts of the Belt Line until the 1970s when increased road infrastructure eliminated the need for rail service. In 1988, the city acquired the land and began converting the railway corridor into a recreational path. The resulting trail was completed in 1993 and named the Kay Gardner Belt Line after a city councillor who had spearheaded the project.

https://www.blogto.com/city/2015/01/a_brief_history_of_torontos_lost_railway_system/

2. Nathan Ng, "1892 Map of Toronto & Suburbs Shewing the Location of the Toronto Belt Line Railway," Historical maps of Toronto, Accessed Sept. 27, 2022.

http://oldtorontomaps.blogspot.com/2013/01/1892Map-of-Toronto-Showing-BeltLine-Route.html

3. Nathan Ng, "1892 Map of Toronto & Suburbs Shewing the Location of the Toronto Belt Line Railway" Historical maps of Toronto," Accessed Sept. 27, 2022. http://oldtorontomaps.blogspot.com/2013/01/1892Map-of-Toronto-Showing-BeltLine-Route.html

4.Chris Bateman, "The history of Toronto's lost railway system"

https://www.blogto.com/city/2015/01/a_brief_history_of_torontos_lost_railway_system/

5. Chris Bateman, "The history of Toronto's lost railway system"

https://www.blogto.com/city/2015/01/a_brief_history_of_torontos_lost_railway_system/

6. Derek Boles, "Toronto Belt Line - 1892," Toronto Railway Historical Association, last modified 2017, https://www.trha.ca/beltline.html

Railways on the Esplanade

Toronto Railway Story

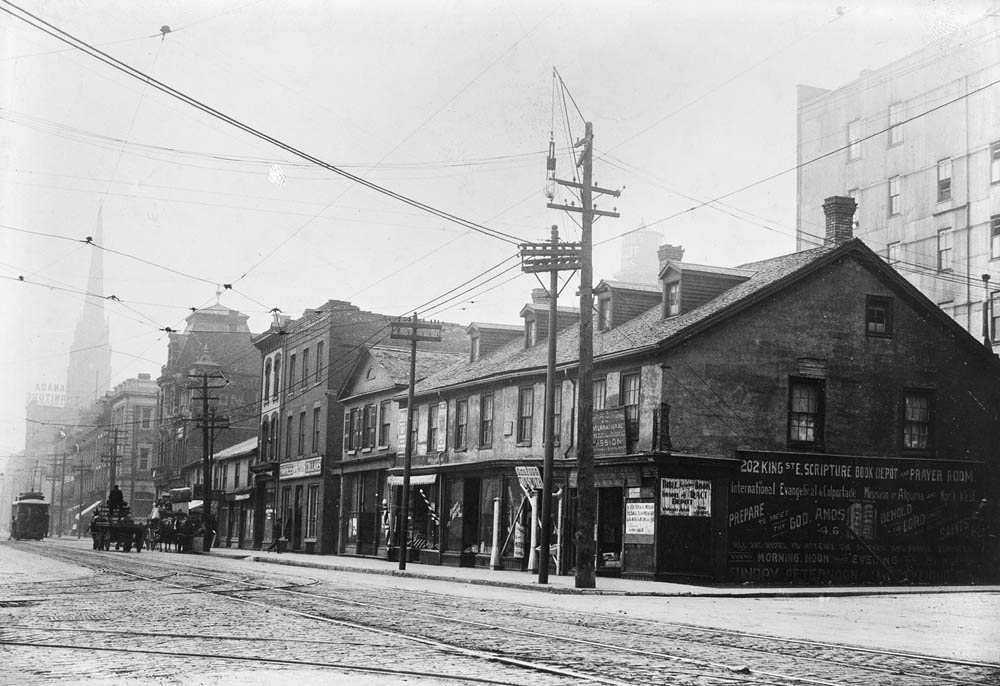

This painting by John Howard shows Toronto's Esplanade as it appeared in 1854. Today, the Esplanade is home to a vibrant residential community in which some 15,000 people live. The Crombie and Parliament Square Parks provide ample green space, and accessible housing in the area allows for the creation of a socially diverse neighbourhood.Yet this wasn't always the case, and the history of the Esplanade is steeped in industry and economics. Railway giants fought for space in an area that was once crowded with railroad tracks, freight sheds, and warehouses. Pedestrians dodged trains and navigated crowded platforms throughout what quickly became one of Toronto's main transportation hubs.

* * *

While industry was the early Esplanade's fate, it wasn't, at first, the vision that Toronto residents held for the new street. Original plans for the Esplanade hoped to clean Toronto's waterfront up and provide clearer access to a shoreline that had become cluttered with wharves and warehouses. In the early 1800s, the young city was pressed up against the shores of Lake Ontario, and the harbour was crowded. The Esplanade was originally slated to be a 30-meter wide road that would be built on in-filled land, extending the city farther into the lake. This vision was not to be, however. It, like so many things in the early history of Canada, would be forever changed by the railways.

The timing lined up. While plans for the Esplanade were being drawn up, railway giants were searching for a way into the city. With real estate already in short supply, the prospect of securing a route for tracks all the way through the city was daunting. The alternative however—bypassing the city entirely—would force railway companies to lose out on Toronto's valuable economic prospects. By 1856, the Grand Trunk railway had already built railway track on both sides of the city and were using horse-drawn omnibuses to ferry passengers across Toronto. The company needed new land, and the Esplanade would make it for them, transforming lake into solid earth. They struck a deal with local politicians: in return for a 12-meter-wide stretch of the Esplanade, the company would underwrite the cost of infilling the harbour.

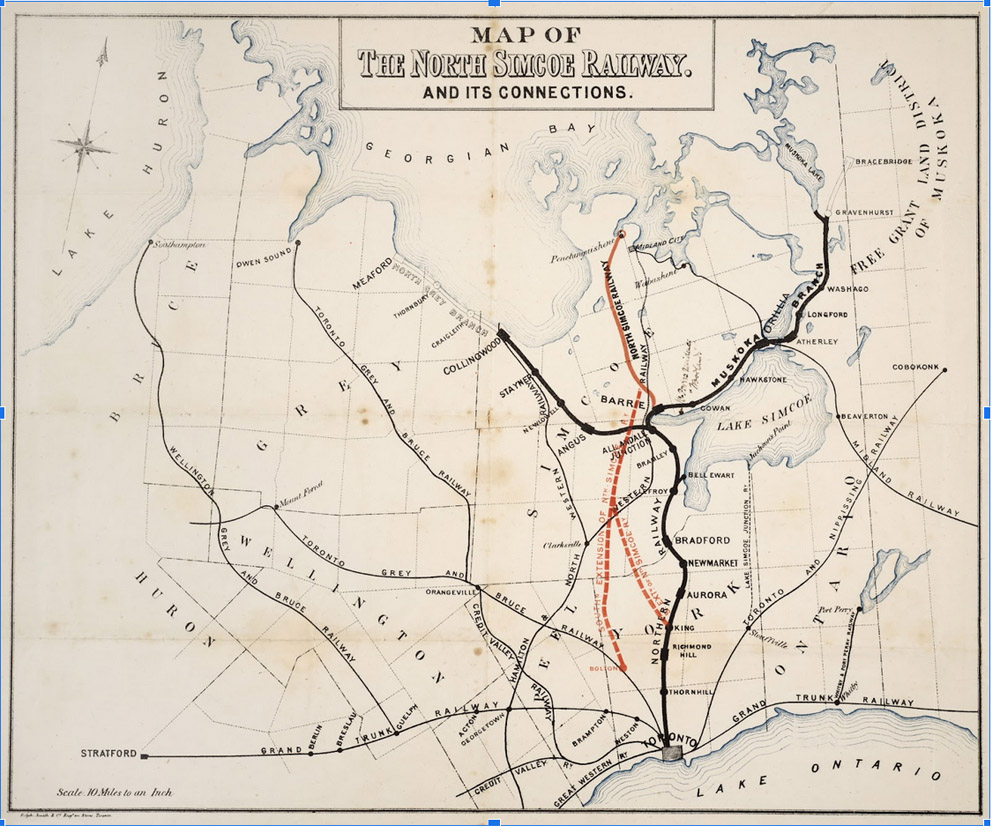

This, on top of the economic promise posed by the railway, was enough to secure the deal, and once the Grand Trunk Railway set up shop along the Esplanade, other railways soon followed. In 1858, the first Union Station opened along the Esplanade, completing the railway connection across the city. It was the first of many stations that would open in the area, and it, like those to come, quickly became overcrowded. Among the railway companies which would come and go throughout the years along the Esplanade were the Grand Trunk, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway, the Great Western, the Toronto & Nipissing Railway, the Credit Valley Railway, the Canadian Northern Railway, and, of course, the famous Canadian Pacific Railway. At one point, all train traffic which entered or left Toronto from the east travelled along the Esplanade.

While not all of these railways required either their own tracks or their own stations, the Esplanade soon became crowded. The tracks which crisscrossed the road posed a real danger to pedestrians and other road users, since there were neither underpasses nor bridges built to separate trains and foot traffic. By 1866, for instance, no fewer than seven tracks crossed the nearby Yonge Street.1 Traffic control, once it was established, was minimal: manual gates were operated by a railway employee perched in a short tower with a view of the oncoming tracks.

By the time the 20th century dawned, it was clear that a solution needed to be found soon for the overcrowding issue. Unfortunately, neither the city nor the railway companies could agree on who, exactly, was responsible for finding (and funding) this solution. The construction of over- or underpasses would be expensive and time consuming, and it wasn't a burden anyone wanted to take on. Then, in 1904, a surprising solution was born from tragedy—The Great Fire of Toronto. The fire raged through the city east of the original Union Station. It destroyed more than 100 buildings, and, in consequence, created a whole lot of empty land on which to start fresh. A new Union Station was built on this land in 1914, and within a decade, a new railway corridor was being created away from the Esplanade, complete with grade separation that would protect pedestrians. It was completed in 1930, and gradually, the Esplanade became far quieter.

Other changes had taken place for the Esplanade too. In the 1920s, the harbour was filled in farther, and the Esplanade had its shoreline taken from it as the waterfront moved farther south. For several decades, the neighbourhood fell into decay. Almost all of the railway traffic moved away, and the warehouses gradually closed. Vast areas fell into disuse, becoming seas of empty parking lots.

Then, in the 1970s, the city breathed new life into the Esplanade through a project of urban renewal. The so-called St. Lawrence Neighbourhood was planned and built in the area. Empty railway yards were converted into parks, and brick row houses, townhouses, and eight- and ten- storey apartment buildings were built to provide more accessible and affordable housing. A community grew up where industry had once thrived. Today, some of the last traces of the Esplanade's history exist towards its eastern end, in the Distillery District, a national historic site that boasts the largest collection of Victorian-era industrial buildings in North America. Here still, if you look closely, you can catch glimpses of the Esplanade's rich railway history.

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located at the John Street Roundhouse in downtown Toronto. You can also take a virtual tour and two audio guided tours of the museum and its exhibits in the On This Spot app. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

Toronto's Changing Shoreline

Toronto Railway Story

This was the original location of Toronto's Harbour Commission offices, which oversaw the expansion of Toronto into Lake Ontario.

When the small town of York was first founded on the banks of Lake Ontario, the area around it was full of lush marshlands, wilderness, and waterways. But throughout the years, as the city grew and expanded into today's Toronto, the shoreline changed in drastic ways that would make it unrecognizable. When the city was first founded, the aptly named "Front Street" fronted the water of Lake Ontario, but during the next two centuries, the downtown core would be expanded and the lakefront moved slowly backwards. Today, Toronto's waterfront is a stark example of the ability of humans to drastically reshape their surroundings.

* * *

In the early years of the town of York, during the beginning of the nineteenth century, transport to and from the town consisted largely of boats. There were few roads during that time, and the ones that had been built were rough and difficult to travel. The lake provided York with easy access to the rest of Canada, and its waterfront therefore became busy. Industry and manufacturing crowded along the lakefront, fighting for access to the water. By the 1830s and 1840s, there was little space for any more growth. Then, in the early 1850s, the railway came to Toronto, bringing with it an increase in industry to the young city. Yet if the city was to expand any further, it needed to solve its real estate problem—it needed to create more waterfront.

The first expansion of the downtown core took place in the 1850s, with the reclamation of land south of Esplanade. This infilling of the harbour was only the first of many that would reshape Toronto's downtown. And while the waters of Lake Ontario were being reclaimed for real estate, something else was happening to the city's marshes. When York was still a young town, the area around the mouth of the Don River was known as "The Ashbridges Bay Marsh", and was described in 1794 as "low lands covered with rushes, abounding with wild ducks and swamp blackbirds.”1

Within a century, however, the marsh habitat would be devastated by pollution and sewage from York, and from the many mills built along the waterway. Then, in the 1870s, the inhabitants of the area built breakwaters throughout the river, and in the 1890s, the Keating Channel entirely redirected the Don River. The death knell of the marshes officially sounded in 1912, when the Toronto Harbour Commission moved forward on a plan to transform the Ashbridge Bay Marshes into a massive industrial area. Within a decade, 500 acres of the marsh had been filled in, and there were plans to fill in another 500 acres. Industry grew over the marshlands until they had been all but forgotten.

Meanwhile, the expansion of the waterfront continued. The city continued to grow. The railway was soon built on the first section of infilled harbour, and still, the shortage of real estate continued. Along with the transformation of the Ashbridges Bay Marsh into a new industrial port, the harbour was dredged to accommodate sea-going vessels, and more wharves were constructed. In the 1920s, another wave of land reclamation took place, continuing the expansion of the harbour lands.

Then, in the 1950s, the city of Toronto underwent the process of suburbanization. Those who could afford to do so moved away from the downtown core and into the wealthier suburbs. Yet they still needed to commute to work downtown, and so a new wave of development overtook Toronto: the building of roads. The Gardiner Express was constructed along the waterfront in 1958, cutting the lakefront off from the rest of the city. The Don River was even further lost to the city, its shores crowded with off-ramps and bridges. For decades, the waterfront remained an industrial port zone, and for Toronto's citizens, there was little chance to access the shore.

In more recent decades, however, there has been a movement by Toronto to revitalize its waterfront. In 1999, as part of a bid to host the 2008 Summer Olympics, a task force was created to look into the redevelopment of the waterfront, and while the Olympic bid failed, the taskforce did not. It concluded that redevelopment of the waterfront would create "a major, positive economic impact on the City, the region and the country.”2 The Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Corporation, now simply known as Waterfront Toronot, was founded in 2001, and in the last two decades, the character of Toronto's waterfront has gradually shifted. Today, the harbour has become a recreational district filled with condominiums and new parks. The redevelopment efforts continue into the present, proving that there is no limit to the amount of times humans can redefine the spaces they inhabit.

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located at the John Street Roundhouse in downtown Toronto. You can also take a virtual tour and two audio guided tours of the museum and its exhibits in the On This Spot app. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

2. "History and Heritage." WATERFRONTtoronto, https://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/about-us/history-heritage.

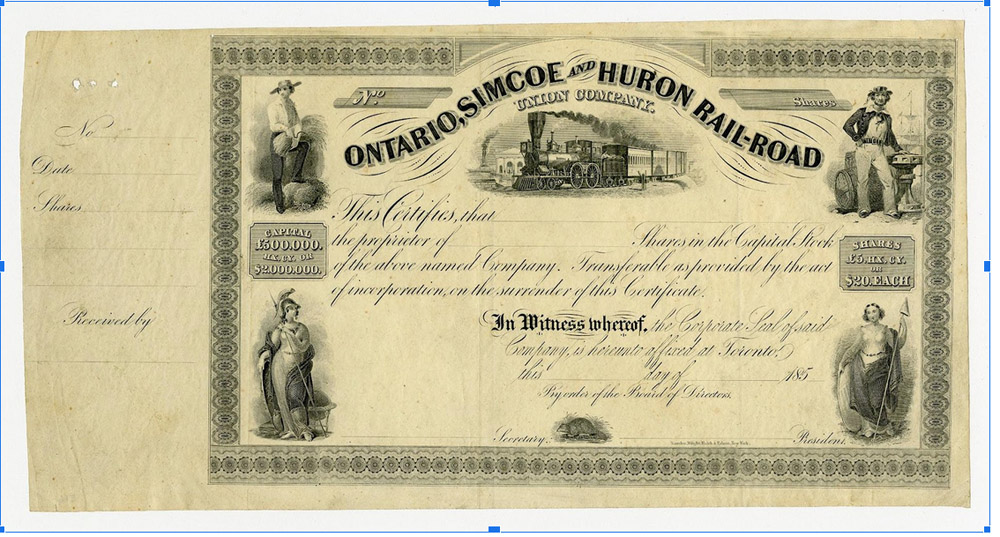

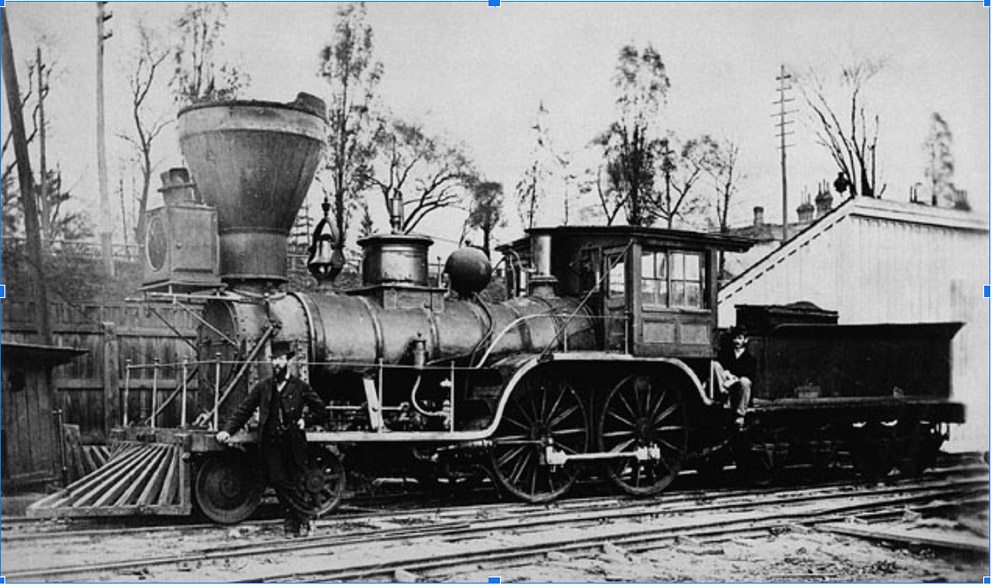

The Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway

Toronto Public Library JRR1111

Toronto Railway Story

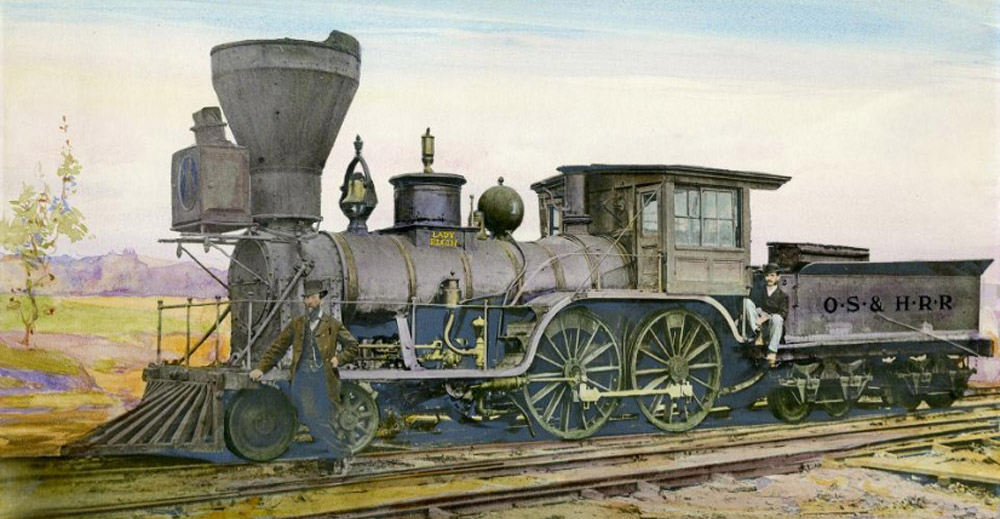

The first railway to come to Toronto was the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway. Talk of bringing a railway to Toronto began as early as 1836 with business men and merchants musing about the benefits it could bring, however the first railway would not begin to take shape until 1848 when Frederick Chase Capreol began to put the ideas together to create a business.1

It was not going to be smooth sailing. The Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway is a tale of money, tragedy and miscalculation.

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located at the John Street Roundhouse in downtown Toronto. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

* * *

Frederick Chase Capreol was quite the character in railway history, in which there are many eccentric businessmen and swindlers. Born in 1803 in Britain, Frederick Chase Capreol emigrated to Montreal in 1828 to work with the fur trade. After a brief return to his hometown of Hertfordshire, he and his wife settled in York in 1833. Capreol fancied himself something of a renaissance man dabbling in real estate and as a pedlar of Queen Victoria portraits as well as operator of an auction house.2

It was the auction house that made trouble for Capreol, although one might suppose that it was actually he himself that made the trouble. Dabbling in land sales Frederick Chase Capreol sought out a large section of land near the Credit River to purchase and auction off. The owner of the parcel was known to drink to excess and be "of unsound mind" so, as part of his negotiation strategy, Capreol had the land owner over to his estate to convince him to sell. For two days Capreol brought him one drink after another and eventually the papers were signed for the sale. The Court of King's Bench overturned the agreement due to the circumstances and the social elite and financiers of Upper Canada knew Capreol as suspicious and not to be trusted.3

Yet there is another story about Frederick Chase Capreol that deserves telling; in 1843 a friend of Capreol called Thomas Kinnear and his lover were murdered gruesomely. Kinnear was shot in the chest and his pregnant lover was found strangled with an axe in her head. When their bodies were found in the cellar of the Kinnear Estate it was immediately obvious who the culprits were. Kinnear estate domestic servants Grace Marks and James McDermott were thought to have committed the murder and feld. Capreol, upon hearing of the murder of his friend and the escape of the accused, implored the police to go after them. Displeased with their slow response, he took it upon himself to charter a locomotive and chase after Grace Marks and James McDermott himself. Capreol tracked them down in Lewiston, New York and apprehended them bringing them back to the Province of Canada to have them convicted in the court. Many things would come out in the landmark trial of Marks and McDermott. Ultimately McDermott was hung and Marks was spared the noose but sentenced to life in prison.4

Perhaps it was this chase that spurred Capreol's obsession with a railway, it was only five years later that he began promoting a railway to Georgian Bay. In 1849 Capreol became the director of the Toronto, Simcoe and Lake Huron Rail Road Compnay (would eventually become called Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway Company.)

The new director of the railroad company Capreol's first order of business was to find a way to fund the project. Rather than asking for a lump-sum from the British Crown, Capreol's bright idea was to host a lottery. It was announced on the first day of 1851 that 100,000 raffle tickets would be sold for $20 each and the prizes would be as follows:

* 2 magnificent allotments of $100,000 in stock $ 200,000. 6 splendid allotments of 40,000 in stock 240,000. 10 extensive allotments of 20,000 in stock 200,000. 16 large allotments of 10,000 in stock 160,000. 20 allotments of 5,000 in stock 100,000. 50 allotments of 2,000 in stock 100,000. 100 allotments of 1,000 in stock 100,000. 250 allotments of 500 in stock 125,000. 500 allotments of 250 in stock 125,000. 2500 allotments of 100 in stock 250,000. 5000 allotments of 50 in stock 250,000. 7500 allotments of 20 in stock 150,000.*5

Total the lottery would amass the 2 million dollars necessary to begin laying ties for the railroad and stock would be divided not according to how much one purchased but by random selection. Though it was a creative and unique idea that captured attention, it was dropped and Capreol once again was thought to be madder than ever continuing his legacy of unconventional and less than ethical means of business. After this debacle the rest of the directors midtrusted Capreol and he was removed from the management being referred to as "mad Capreol" by the business community in Upper Canada.6

Ultimately, it was a change in legislation that allowed for the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway to begin its construction. The Guarantee Act and the Municipal Loan Fund pioneered by Francis Hincks were instrumental in accumulating the funds for Toronto's first railway. The Guarantee Act was passed in 1849 and stated that a railway project "over 120 kilometres long would be eligible of a government guarantee on the interest of half its bonds as soon as half the line had been completed." Essentially, the government of the Province of Canada would have stake in half of any line over 120 kilometers providing half of the funding. This change in legislation cut the amount of funds the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway had to come up with in half.7

The Municipal Loan Fund was another policy created by Francis Hincks, who had great interest and investment in the Canadian Railways at the time, and was passed on November 10, 1852. This act allowed municipalities to borrow money for capital projects on the credit of the Province of Canada. The idea was to increase capacity for cities and towns to improve infrastructure and make Canadian municipalities more desirable. By 1855 over 7 million dollars had been borrowed by municipalities after promoters of railway companies pushed towns to borrow to pay them for their projects. The lending was stopped in 1854 after little return on investment made it impossible to defend as an economic policy.8

Both policies fell out of favour eventually as they were high risk and economically irresponsible. The railways that benefitted from such policy, including the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway, made little money and left the Province of Canada with worthless shares and in debt to the British Crown.9

Despite a long and arduous journey of financial upheaval and questionable leadership, the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway was opened on May 16, 1853 and service expanded to a variety of locations over the next year. The port on Lake Huron was finally complete in early 1855. The pride of finishing the railroad would only last a short time however. Poorly built, the railway was in frequent disrepair and accumulated debt consistently. Despite their best efforts the directors were not able to recoup the losses and the Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway was eventually absorbed into the North Western Railway Company.10

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located at the John Street Roundhouse in downtown Toronto. You can also take a virtual tour and two audio guided tours of the museum and its exhibits in the On This Spot app. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

2. Cooper, Charles, "The Northern Railway of Canada Group." Online

3. Baskerville, Peter, “CAPREOL, FREDERICK CHASE,” Online.

4. Katz, Brigit, "The Mysterious Murder Case That Inspired Margaret Atwood's 'Alias Grace'" Online.

5. Cooper, Charles, "The Northern Railway of Canada Group." Online

6. Cooper, Charles, "The Northern Railway of Canada Group." Online

7. Fahey, Curtis. "Guarantee Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Online.

8. McCalla, Douglas. "Municipal Loan Fund." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Online.

9. Fahey, Curtis. "Guarantee Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Online.

10. Cooper, Charles, "The Northern Railway of Canada Group." Online

Bibliography

Baskerville, Peter, “CAPREOL, FREDERICK CHASE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed March 4, 2022, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/capreol_frederick_chase_11E.html.

Brown, Robert R., "Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway." Railway & Locomotive Historical Society (No. 85 Spring 1952). 35-41.

Cooper, Charles, "The Northern Railway of Canada Group." Charles Cooper's Railway Pages (2014) https://www.railwaypages.com/northern-railway-of-canada-group

Fahey, Curtis. "Guarantee Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

Katz, Brigit, "The Mysterious Murder Case That Inspired Margaret Atwood's 'Alias Grace'" Smithsonian Magazine. November 1, 2017. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/mysterious-murder-case-inspired-margaret-atwoods-alias-grace-180967045/

McCalla, Douglas. "Municipal Loan Fund." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published February 07, 2006; Last Edited March 04, 2015.

Toronto Railway Museum, "Toronto's First Railway." March 3, 2021. https://torontorailwaymuseum.com/?p=807#:~:text=Toronto's%20First%20Railway%20Complete&text=It%20would%20be%20the%20first,(present%2Dday%20Aurora).

Union Station: A Memory for All

Toronto Public Library E 1-33a

Toronto Railway Story

Union Station as it stands today has become the pinnacle of railway history in Toronto. As the central stop for trains for well over a century Toronto's Union Station has welcomed immigrants and newcomers, served as a stopping point for ventures west and been an architectural statement for many decades.

The building that stands today was actually not the first Union Station however. The original Union Station began construction in 1872 on Front Street and Simcoe Street and was completed in 1895. The station was meant to resemble the Central Station in Chicago with tree domed towers including a clock tower. It contained in its walls a ticket counter, waiting rooms, and railway offices along with two train sheds on the grounds. The station was considered quite beautiful in its modern style and was a prominent feature of the early Toronto skyline.1

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located in downtown Toronto. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

* * *

By 1911 the station was receiving 130 trains everyday and upwards of 40,000 passengers! It was decided that a larger station was needed to accommodate the volume of passengers and trains to growing Toronto.2

Construction began on the new station in 1913 but was stagnated by the first world war. Though it took longer than expected to finish, Union Station was eventually the largest urban station to be built in the 20th century and was designated as a protected heritage resource by Parks Canada in 1975.3

Despite competition for freight and passengers, [rival railroads] found reasons from time to time to cooperate, as in their joint use of Totonto's monumental Union Station. A legacy of the Grand Trunk and twelve years in the building, it remained unfinished until the [Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway] completed the work and the Prince of Wales presided over the opening ceremony on Canada's birthday in 1927.4

The Union Station was designed in Paris by G.A. Ross, R.H. MacDonald, and Hugh Jones of the Canadian Pacific Railway as well as John M. Lyle of Toronto. It was built in the Beaux-Arts style with barrel vaulted ceilings and large tall windows on the east and west walls. The north and south walls were engraved with the names of the cities serviced by the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific Railways as an impressive show of the span of Canada and grandeur of the rail. The interior was made with stone from Missouri and floors of Tennessee marble with Indiana Limestone making up the exterior of the building.5

The train sheds from the original 1895 station were torn down in 1927 and 1928 with the station itself removed in 1931. However the impressive Union Station as it has been rebuilt still stands resolute and as a symbol of transition and transportation across Canada.6

Union Station has seen millions of immigrants and travelers over more than a century of operations. One of the unique features of a central train station is that nearly every newcomer has stood on those floors, especially during the interwar years and after the second world war. Newcomers to Canada would travel across the Atlantic to Pier 21 and board a train to take them across Canada to their destinations. For those destined for Toronto it was Union Station that was a symbol of relief, the end of a long journey to a new home.

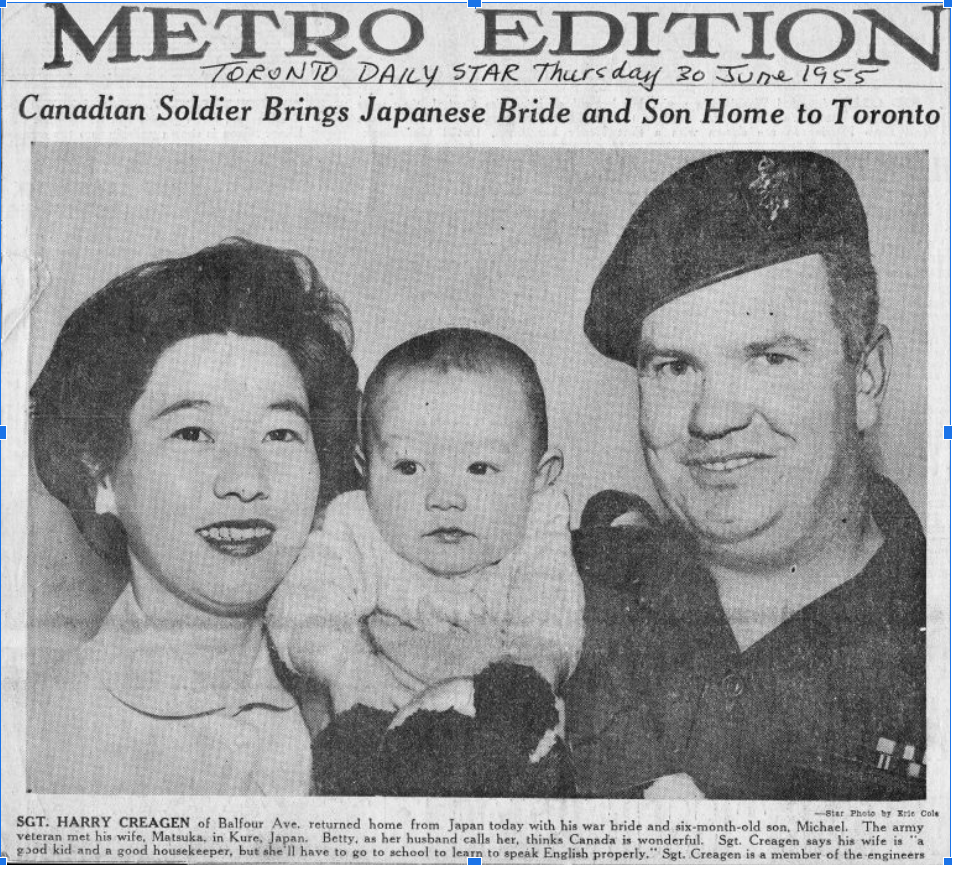

War brides were one of the immigrant groups that arrived in large numbers after the second world war. When Canadian soldiers were overseas they found wives and started families. After the war ended in 1945 soldiers came home and their wives and children soon followed. Between 1942 and 1947 47,783 war brides and 21,950 children arrived in Canada from all across the world.7

One of these war brides was Matsuko Creagen and her son Michael. Matsuko had married Harry Creagen in Japan after the second world war. Harry was a combat engineer during the Korean war, when he fell in love with Matsuko the army did not approve of their relationship and advised Harry against marrying her. Despite their prejudiced advice, Harry and Matsuko were married and had a son in Japan.8

Matsuko Mihara came from a farming family in Japan and had grown up on their tangerine farm in Kure just twenty-four kilometers from Hiroshima. When she reached a marriageable age Matsuko's mother arranged for her to marry into a wealthy family in Japan, but Matsuko declined the union as she did not love him. She met Harry in 1953 when she was working with the British Commonwealth Armed Forces Canteen in her hometown.9

Though they were in love, getting the blessing of Mutsuko's mother and approval of the army was nearly impossible due to traditional ideas and rising animosity between the west and Japan after the second world war. Harry threatened to leave the army if they would not allow him to marry his love and eventually the army consented. In 1954 the couple were married in Japan and the following year welcomed their first son. It was soon after the birth of their first child that they deemed it time to return to Canada and so they set sail across the Pacific in June. After a journey of sixteen days by boat they landed in Vancouver where the family of three boarded a train bound for Toronto. The Union Station was the first bit of Toronto ground that Matsuko and her son set foot on, a place that would be her home for the following years.10

This Story Location brought to you by the Toronto Railway Museum. Discover Toronto's rich and fascinating railway history at the museum, located at the John Street Roundhouse in downtown Toronto. You can also take a virtual tour and two audio guided tours of the museum and its exhibits in the On This Spot app. For more information visit TorontoRailwayMuseum.com

2.City of Toronto, "History of Union Station." Online.

3.City of Toronto, "History of Union Station." Online.

4. MacKay, Donald, The People's Railway. 75.

5. City of Toronto, "History of Union Station." Online.

6. City of Toronto, "History of Union Station." Online.

7. Bonikowsky, Laura Neilson. "Arrival of the War Brides and their Children in Canada." Online.

8. Thorne, Stephen J., "A soldier, a war bride, and a son." Online.

9.Thorne, Stephen J., "A soldier, a war bride, and a son." Online.

10. Thorne, Stephen J., "A soldier, a war bride, and a son." Online.

Bibliography

Bonikowsky, Laura Neilson. "Arrival of the War Brides and their Children in Canada." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published October 18, 2013; Last Edited August 22, 2019.

City of Toronto, "History of Union Station." City of Toronto. Accessed March 5, 2022. https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/venues-facilities-bookings/booking-city-facilities/union-station/history-of-union-station/

MacKay, Donald, The People's Railway. Douglas McIntyre (1992), Vancouver/Toronto.

Thorne, Stephen J., "A soldier, a war bride, and a son." Legion (July 15, 2020). https://legionmagazine.com/en/2020/07/a-soldier-a-war-bride-and-a-son/

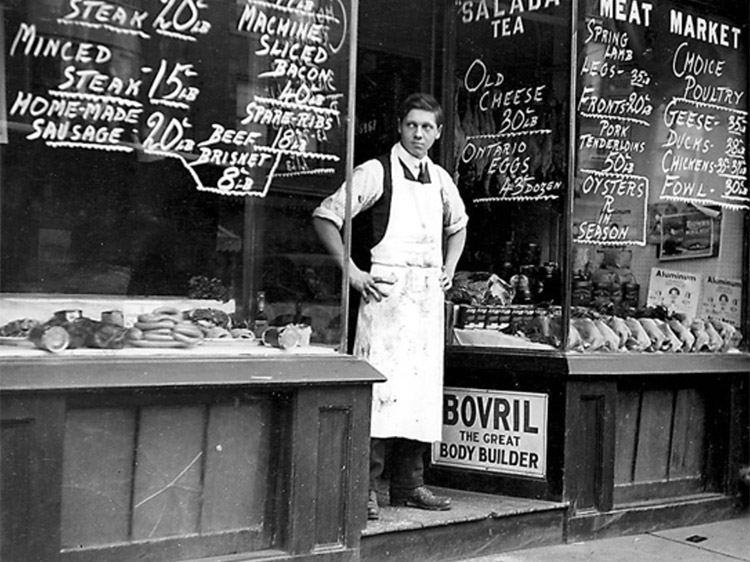

Then and Now Photos

Adelaide Street

Toronto Public Library E 9-207 Small

1874

Horse-drawn carts and piles of rubble line the sides of Adelaide Street. The photo was taken looking east from Victoria Street.

The Old Post Office

1867

Toronto's Old Post Office was built in the Greek Revival Style in 1852. It was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1958.

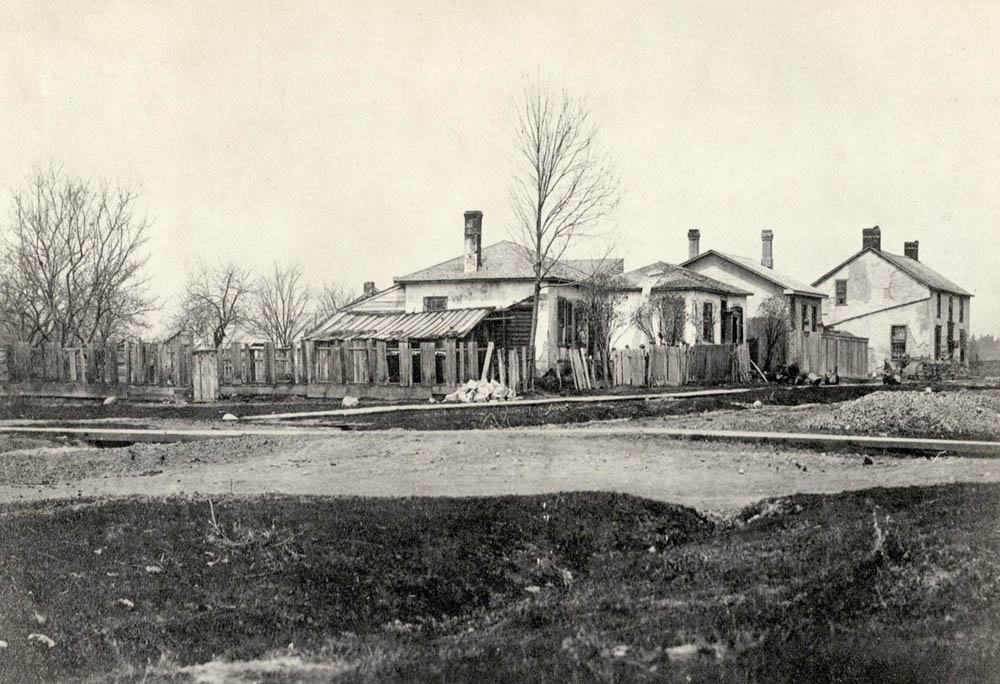

Homes on Spadina

Toronto Public Library E 4-86c

1870

Several simple houses line Spadina Ave, just by College.

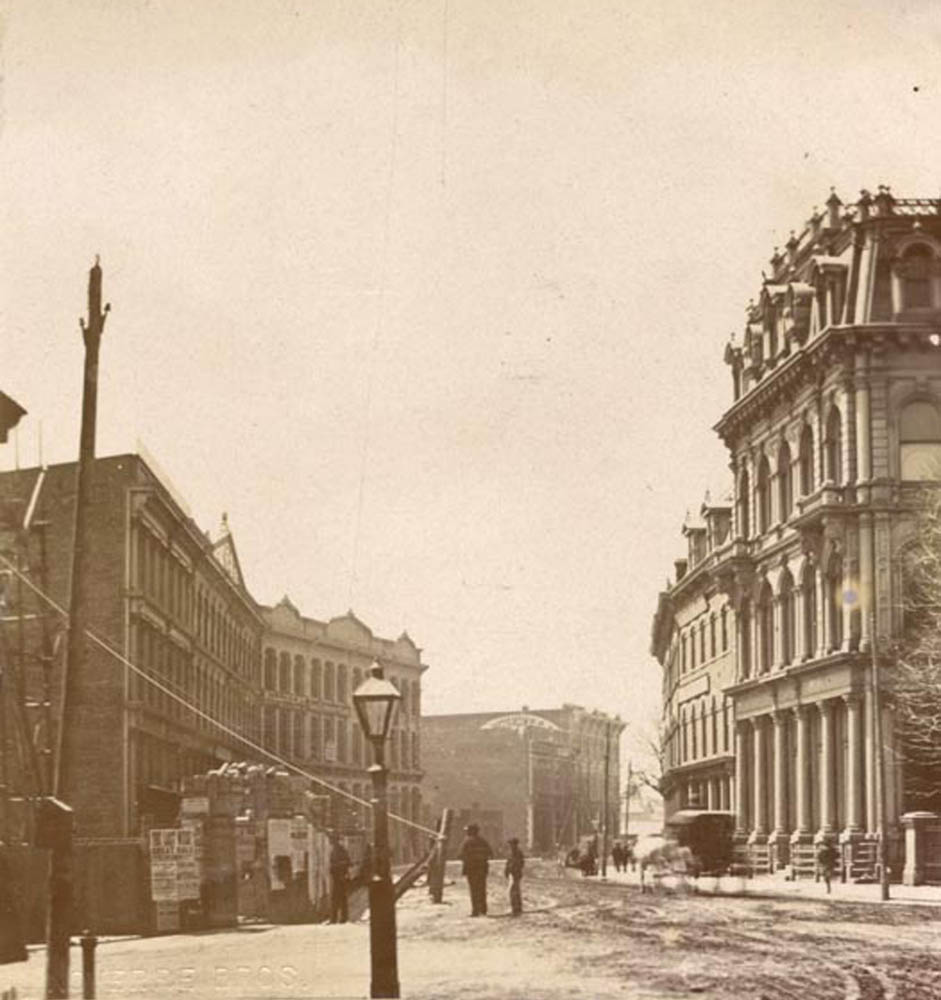

The New Post Office

Toronto Public Library E 2-25b

1873

This view is looking up Toronto Street towards the new post office, which is under construction. You can see the front facade of the old post office at the far left.

News Stand

Toronto Public Library B 12-23d

1875

Several men stand in front of a large news kiosk set up on the sidewalk of Front Street.

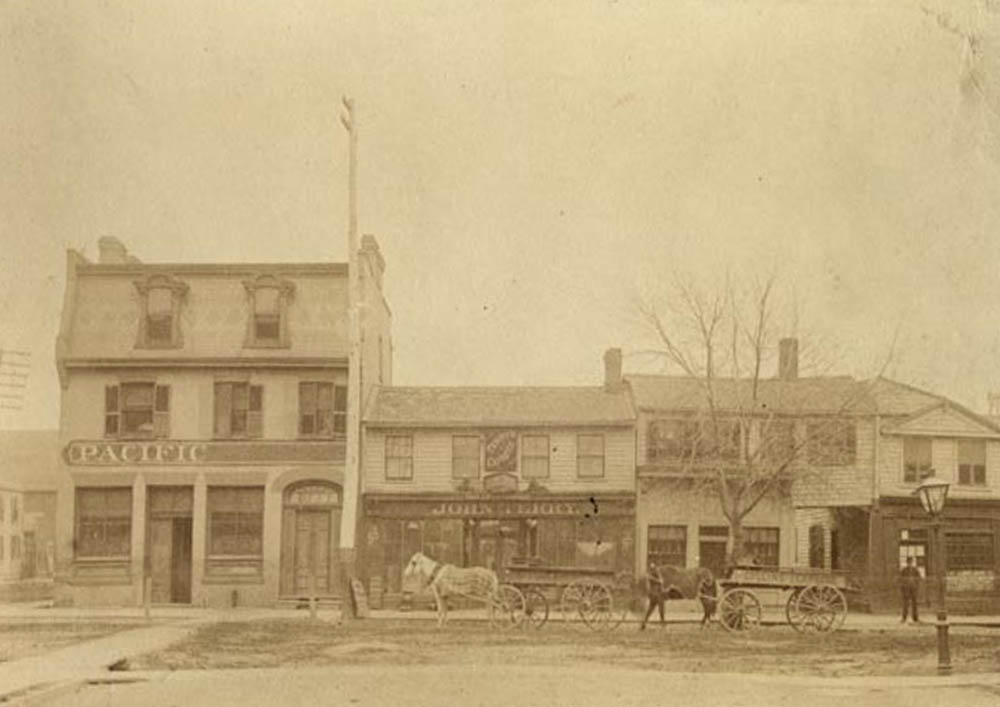

Terry's Express

Toronto Public Library B 11-27b

1885

Carts of Terry's Express service with horses harnessed have been placed in front of the company offices for a portrait. The business seemed to specialize in delivering coal and wood that was used for cooking and heating.

Monro's

Toronto Public Library B 11-21a

1887

The building at right was the warehouse of George Monro.

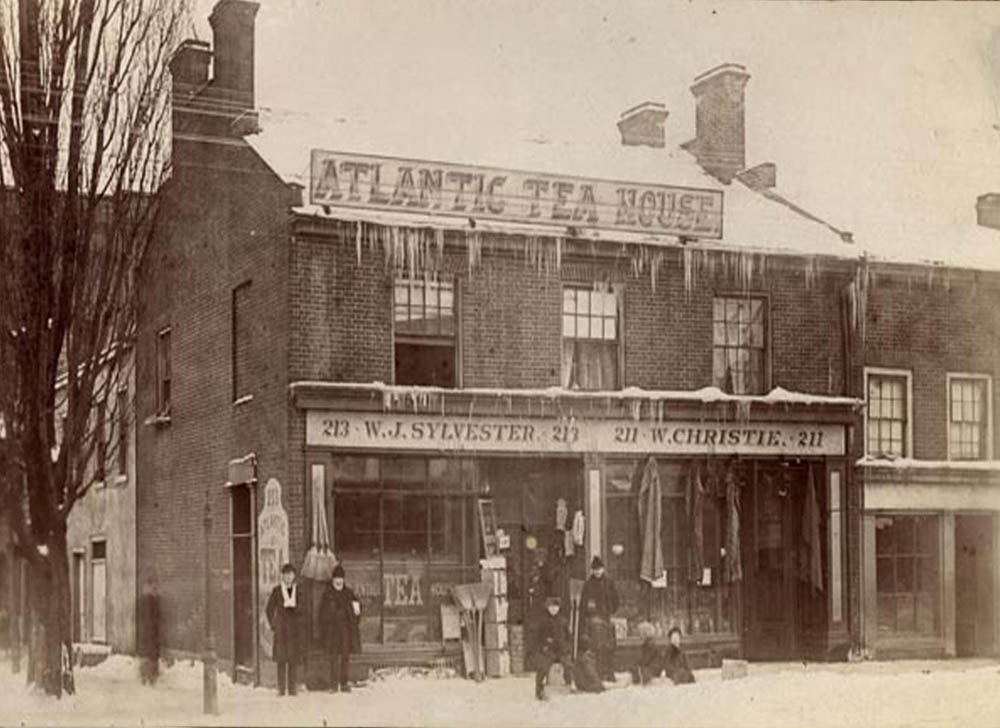

Atlantic Tea House

Toronto Public Library B 11-8b

1885

Several people pose for a photo outside the Atlantic Tea House. Some of the children at the right are having a hard time sitting still for the camera. Brooms and other goods hang on the walls for sale.

A Horsebus

Toronto Public Library E 9-48 Small

1889

The photographer was standing right in front of a horsebus when he took this photo on King Street. The sidewalks are packed full of people.

Old Customs House

Toronto Public Library B 11-47a

1890

The elegant Italian Renaissance style customs house, located at the corner of Front and Yonge Street.

St. Lawrence Market

1898

Up the street alongside the St. Lawrence Market.

Cows at Market

1898

A herd of cows being shepherded into the St. Lawrence Market.

Boer War Decorations

Toronto Public Library -339673

1900

Buildings on Temperance Street have been decorated with bunting to celebrate the return of Canadian troops from the Boer War.

King and Jarvis

Toronto Public Library E 9-229 Small

1909

Some rather simple buildings on the intersection of King and Jarvis.

Dentist Office

Toronto Public Library S 35-16

1910

Showing a business block on Queen Street that survives to this day. The business on the corner houses a drug store and the dentist offices of one Dr. E.F. Willard.

Auctioning Buildings

Toronto Public Library B 13-31a

1910

A cart crosses the street in front of several buildings that have signs proclaiming they are being publicly auctioned.

Blowing Snow

Toronto Public Library X 64-108

1900s

A man steadies his horse as a streetcar threatens to engulf them with a mountain of snow.

Doel House

Toronto Public Library X 64-24

1905

The home of John Doel, photographed some decades after his death in 1871. He was an important reformer politician in early Ontario history, and was a prominent supporter of William Lyon Mackenzie during the Rebellion of 1837.

Doel House (2)

Toronto Public Library E 8-220

1913

The home of John Doel, photographed some decades after his death in 1871. He was an important reformer politician in early Ontario history, and was a prominent supporter of William Lyon Mackenzie during the Rebellion of 1837.

A Traffic Cop on Bay St.

Toronto Public Library B 13-73

1912

A policeman stands in the centre of the intersection of Bay and Adelaide as a cart rolls by.

Busy Bay Street

Toronto Public Library E 2-51a

1930

Cars, streetcars, and pedestrians on Bay Street at the outset of the Great Depression.