Walking Tour

University Driveway to Little Italy

The History of College Street

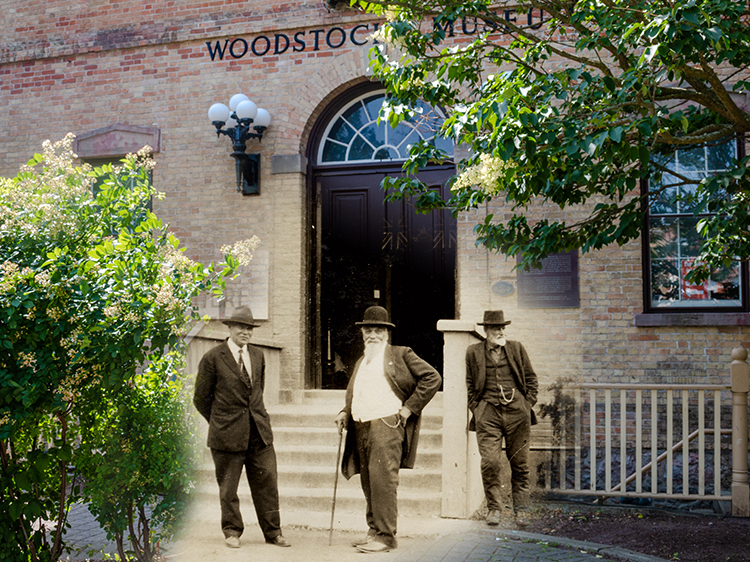

Taylor Peacock

Every single bustling street in Toronto has its own unique story—and College Street is no different. Its story begins with the University of Toronto, early settlers, and land subdivisions. From there, College Street took on a life of its own as it became home to many of the immigrant communities that found their way to Toronto from across the sea.

College Street underwent radical change after two successive waves of Italian immigration left deep cultural imprints on the community. As businesses come and go, College Street's cafes and bars make it a home to Italian communities and a cultural stopping point for Anglo Toronto.

The place to find CHIN radio and traditional Italian cuisine, modern day College Street barely resembles the street of the mid-19th century. Instead, it draws in people from all over the world, creating one of Canada's most diverse melting pots.

So, follow along on this tour as we go back to the early days of College Street and reveal the sordid deeds and inspiring characters that have shaped this neighbourhood.

Starting a little off the beaten path, at the corner of Shaw and Harrison, the first stop on the tour is an extension of the University of Toronto, and a reminder that all roads lead to the university. Walking up to College Street, the next stop unpacks one of the earliest Black Methodist Churches, and examines the origins of College Street's design. From there, we head down College Street, turn onto Grace Street and walk towards Mansfield Street, an important little suburb that is home to one of Little Italy's most important buildings, St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church.

While following Mansfield Street towards Clinton Street, take in the suburb that surrounds the area, where many of Toronto's second-wave Italian immigrants made their homes. Taking a left at Clinton Street, head back towards College Street and stop to appreciate a photo of early homes, and the nearby Monarch Tavern. When you arrive again on College Street, travel down the right-hand side to learn about Portuguese immigration and the bank-robbing Boyd Gang. Then, cross the street to discover legendary local landmarks like Cafe Diplomatico, Cohen's Fish Market, and the Pylon Theatre, while diving into the ugly history of anti-immigration sentiment, the Christie Pits riots, and a new form of entertainment: burlesque. Finally, the tour finishes close to where you began, and we end on a high note that captures one of Little Italy's success stories.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

1. The Early Days of College Street and the University of Toronto

Toronto Public LIbrary E 9-142 Small

1890s

While far from the University of Toronto now, St. Hilda's, the building in front of you, is a reminder that much of the early architecture and planning in Old Toronto centered on the University of Toronto, including Little Italy's College Street.

Looking at a map of Old Toronto, one can't help but notice that all major streets converge at one central hub: the University of Toronto. These streets began as footpaths to the university before evolving into the traffic-filled thoroughfares we know today. College Street was one of those footpaths.

* * *

The neighbourhood that St. Hilda's is part of was tied to the university by College Street. College Street began as one of the university's many roads that were part of the initial 1827 university land grant given to the fledgling town of York, as Toronto was known then, by King George IV under royal charter. As a private road to the university, College Street wasn't publicly accessible until the 1860s, when the public was finally granted access to university lands.2 From the university, College Street's initial path extended all the way to Manning Avenue.

Historian John Ross Robertson described the area in the early 1870s in his book Landmarks: "Spadina Avenue had not more than two dozen houses upon its length north of Queen Street, while College Street, west of Spadina, was thickly interspersed with gardens, corn patches and vacant land."3

In the 19th century, the area around College Street was owned by three families: the Baldwins, the Denisons, and the Crookshanks. While early lots west of the university spanned acres, many of the elite families aimed to earn a pretty penny by parceling off the lots into smaller ones for other wealthy families. As immigrants poured into Toronto near the end of the 1800s, the twin processes of subdivision and densification accelerated. Large pastoral estates were cut up into smaller family-sized farming plots. Those plots were divided into suburban home lots with small gardens, and those cut up again into narrow commercial frontages and rowhouses.

Robertson saw an area of vacant lots, gardens and corn fields, but less than thirty years later, a thriving working class neighbourhood had taken root.

2. College Street's Early Days

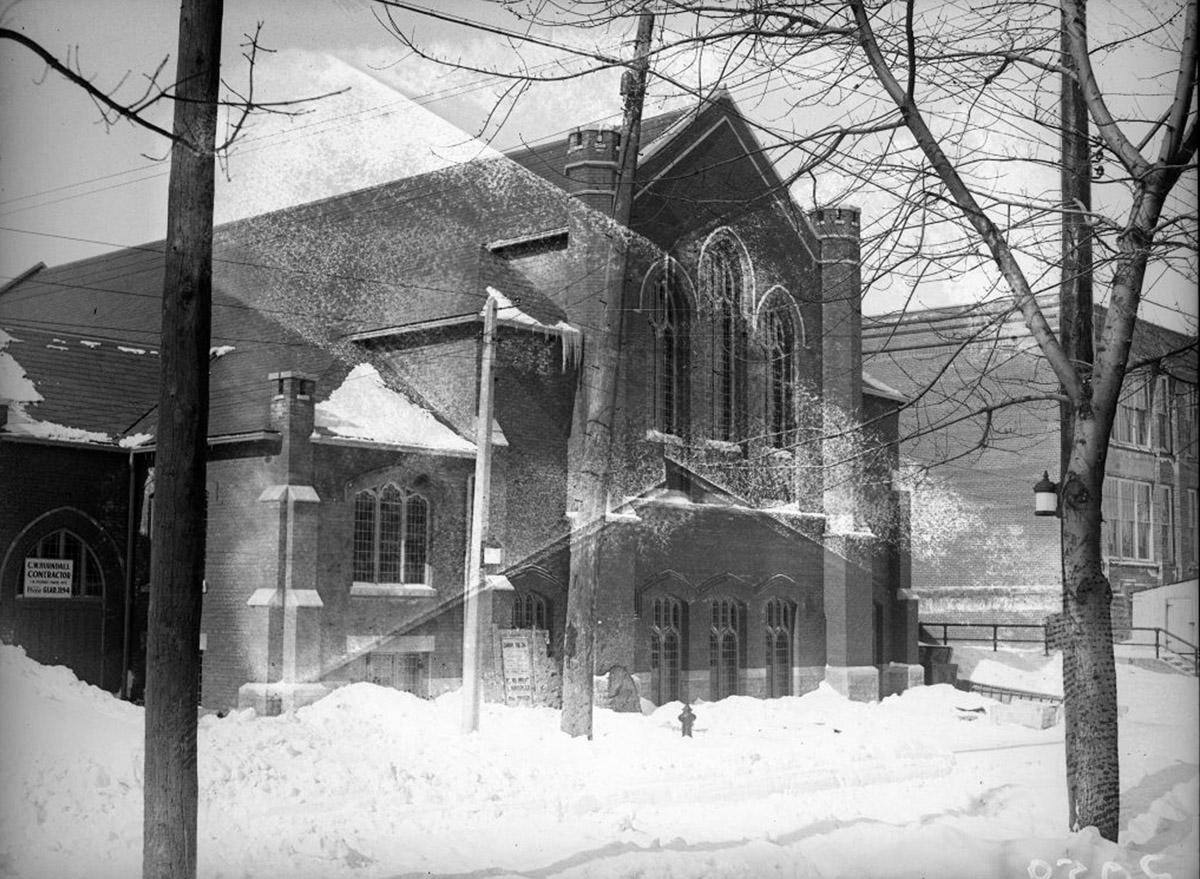

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1266, Item 2059

1924

If any building is emblematic of the working class and immigrant history of College Street, it is the now non-existent Christ Church St. James, which was located just north of College and Shaw.

Erected in 1924, Christ Church became a force in the community in the 1950s when it was purchased by the amalgamated Afro-Community Church and British Methodist Episcopalian (BME) Churches to serve College Street's BME community.

By the time the church was destroyed in 1998, there were around 200 members.1

* * *

One of the most notable BME churches in Canada is Salem Chapel, the church that Harriet Tubman attended. Located in St. Catherines, Ontario, this church is now a recognized historical landmark. In the 1950s, the BME moved from Chestnut Street to Christ Church near College and Shaw, and joined the cultural tapestry of Little Italy.2

Yet the development of College Street as a diverse working class community made up of people from all walks of life was a far cry from the dreams of the early British residents, who had hoped for a sprawling tree-lined boulevard that extended all the way to High Park. In the 1800s, they'd planned a spacious neighbourhood for elite and wealthy landowners who hoped to cultivate a comfortable life near the university.

In the 1850s, when the drive was initially planned, the street was intended to be wider than the average city street, to allow for multiple carriages to traverse in both directions.2 Trees were planted all along College Street to create a picturesque journey, as noted by an enthusiastic reader of the Globe in 1882. Writing in as "An Old Resident," they wrote, "Again, College-street if extended would, with Carleton-street, form almost a direct line of communication between East Park on the Don through Queen's Park in the centre, and High Park on the Humber, making one of the most delightful drives in the city...3

The writer is referring to the tract of land that had been given to the city by architect John Howard in 1876 to become High Park, and which at the time was inaccessible to College Street homes because College Street ventured no further west than Manning Street. The 1846 subdivision of former Crookshanks land further exacerbated the problem: now the land between Manning Street and High Park was privately owned by several families, instead of just one.

The extension of College Street that would later become the epicentre of Little Italy was finally allowed in 1879, when the city engineer managed to acquire $2000 dollars (close to $50,000 today after inflation) for the addition of the streetcar. 4 The dream of College Street becoming a haven for elite landowners would slowly die out.

3. Traveling to Canada

City of Toronto Archives, Series 71, Item 11506

1936

There are very few things as notoriously Torontonian than its streetcars. A massive system that connects the neighbourhoods, the streetcar system of Toronto is as important a piece of its history as it is a part of the cultural landscape.

The streetcar in Toronto has been in use since the 1860s, when the first cars were pulled by horses—omnibuses, as they were then called. The city replaced horses with electric current tracks like the ones on College Street at the end of the 19th century, firmly cementing the streetcar in Toronto's landscape. When tracks were laid along College Street and the route was expanded, it meant more than just a connection to wider Toronto as a whole. For the Italian Canadian community of College Street, the streetcar tracks meant the growth of the businesses and homes they had created.

* * *

"A friend of mine, whose family also emigrated from southern Italy, described life in those towns back home as sufficiently hardscrabble that engaging in commerce amounted to walking miles to the next village to trade your potatoes and figs for someone else’s potatoes and figs. The intractable old-country poverty must have made the crowded, filthy conditions of The Ward look like hope and possibility - a sensible pooling of risk in order to have a shot at a richer, easier life. My great-grandfather pushed his fruit cart north and south, east and west. He saved enough to transition from itinerant vendor to shopkeeper, setting up a small store for his son (my maternal grandfather) and his bride as a wedding present. It was given alongside a pronouncement that he and his wife would be coming to live with the newlyweds." 2

While Italians were emigrating all over the world en masse, Canada was not really considered a point of landing until 1850, when work in the agricultural sector became a significant possibility. The Italians that came to Canada, however, had other plans, and 'little Italies' were developed out of the need for a community chain that would allow individuals to move to a new country and not be completely adrift. In this neighbourhood, Salvatore Turano's store on Mansfield Street was the first boardinghouse and community refuge that received recently landed Italian immigrants. Between the Ward and Little Italy, throughout the early 1900s, various businesses and homes acted as ports that received individuals who had just arrived and helped them get sorted.3

In Toronto's post-war period, the second wave of immigration bore resemblance to its earlier counterparts, but with some key differences. The vast majority of migrants in the 1950s and onward were young men who had largely family based goals. They needed not so much to escape 'la miseria' but to build a solid foundation to either bring their family to or build a family upon. By the mid 1950s, there were also a notable number of women travelling to Canada in family units. Like their much earlier counterparts, however, they relied on the existing community organisations to settle into their new homes.4

Throughout the early parts of the 20th century, various organisations like Salvatore's store were a crucial component to the early immigration experience, and the formation of these communities into what we see today.

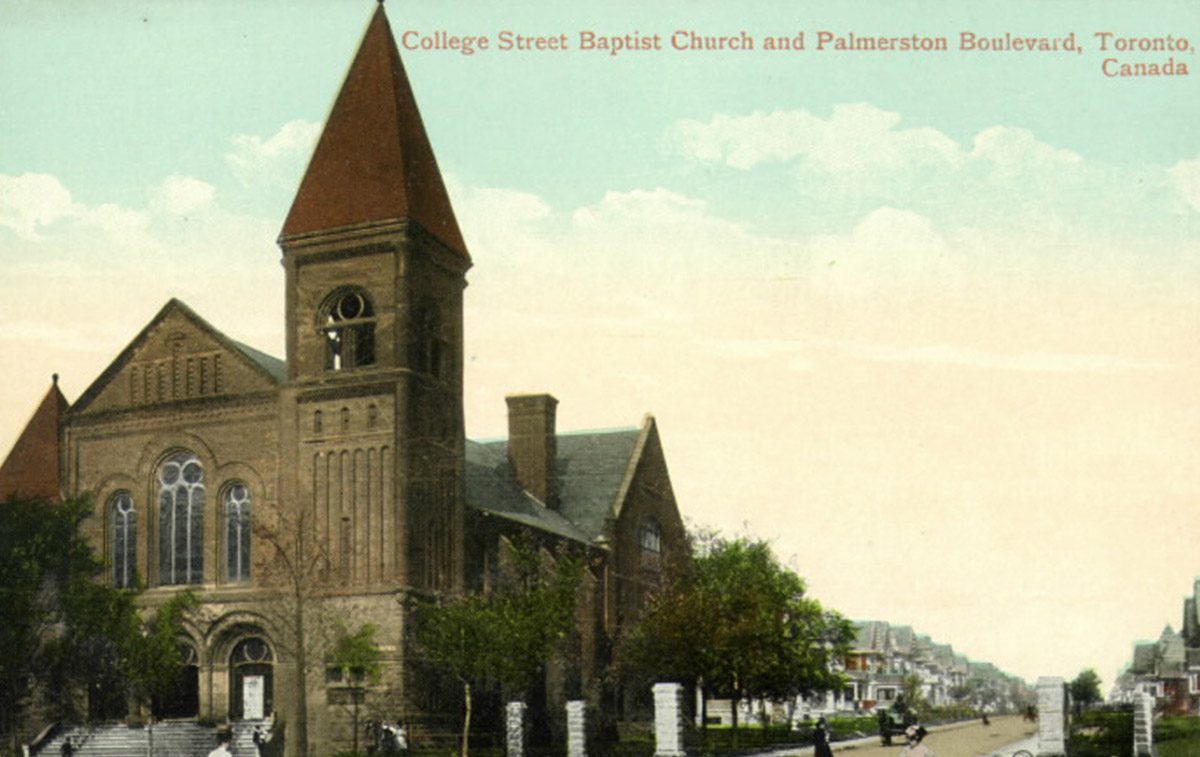

4. Religion in the College Street Community

Toronto Public LIbrary X 65-168

1922

St. Francis of Assisi is still an active Roman Catholic Church, and time has not lessened the importance of religion in this community.

The Church of St. Francis of Assisi is very nearly as old as the Italian community in Little Italy. While the building in front of you was built in 1915, the parish of St. Francis originally attended the Church of St. Agnes, on the corner of Grace and Dundas Street. Founded in 1902, the community began not in Italian pastoral care, but Irish. The Irish were among College Street's earliest inhabitants while many Italians were still in the Ward. For the Irish immigrants of Toronto, this holdfast of the religion from their home country was an important part of settlement in Canada.1 In 1913, however, Toronto's archbishop transferred the parish to Italian control, as many of the Irish immigrants had moved on, and the streets were instead filled with Italian families.

* * *

Throughout the 20th century, the role of the Catholic churches in Little Italy would also change, as the annual Good Friday Procession grew in popularity, not only attracting Italians, but a diverse array of Torontonians. In the Catholic faith, Good Friday commemorates the crucifixion of Christ, where the fourteen stops associated with the Stations of the Cross commemorate the events of His mile-long journey to Golgotha. Globally, Good Friday processions are performed in Catholic countries.

In Toronto, the procession began sometime between 1953 and 1956—the date is hotly debated—and while it is celebrated now, the occasion was initially shunned by Toronto's Anglo community. Early photographs make it clear that the city refused to stop traffic for the procession, as streetcars are seen nearly running over parishioners. Nowadays, however, the mile-long walk that begins and ends at the church in front of you attracts around 6,000 people, and is a widely recognized civic event.3

5. The Ward

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 33, Item 91

1944

The houses in the above photo are similar to some of the earliest homes in the first immigrant neighbourhood in Toronto, the Ward.

From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, the Ward provided community and housing for immigrants from all over the world as they migrated to Toronto. As a place of poverty, however, the Ward received criticism, and was condemned by Anglo Toronto in the 1920s. In the late 1800s and the early 1900s, the Ward served as the best available low-income housing for many immigrant communities. The Ward as a district was bracketed by College Street to the north, University Street to the east, Shaw Street to the west, and Queen to the south.

* * *

While populated by Jewish and Italian immigrants since the late 1800s, by the early 1900s the state of the Ward was beginning to draw the attention of other Toronto residents. A 1908 article in the Globe and Mail highlights how the views of Toronto's upper class towards the Ward and its residents were not always kind or just: "What is familiarly known as ‘the Ward’ has undergone a radical change in nationality. The little rough-cast houses of Centre Avenue, Terauley, and Elizabeth streets, from which three or four years ago the Irish wash lady wended her way to us on Monday mornings, where the Italian fruit vendor ripened his bananas under his bed at night, and the negro plasterer and barber gave colour to the social scene of a summer evening, have in these later days thrown their shelter over the oppressed Slavonic Jew. Practically the whole Ward is a city ghetto…".2 In 1913, a Globe and Mail article notes that cases of diphtheria and scarlet fever were notably malignant, in part because individuals were living almost on top of each other. When the Medical Officer and police condemned 140 buildings in 1913, they found over 1400 residents living in them.3

For many, however, the Ward was the closest form of home they had, as newly landed immigrant families from across communities were drawn to the Ward. When it was finally demolished in the 1920s and given over to commercial land, many of the remaining families had moved to other parts of Toronto. Little remains of the Ward now.

6. The Boyd Gang's Legacy on College Street

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 200, Series 372, Subseries 58, Item 1244

1930

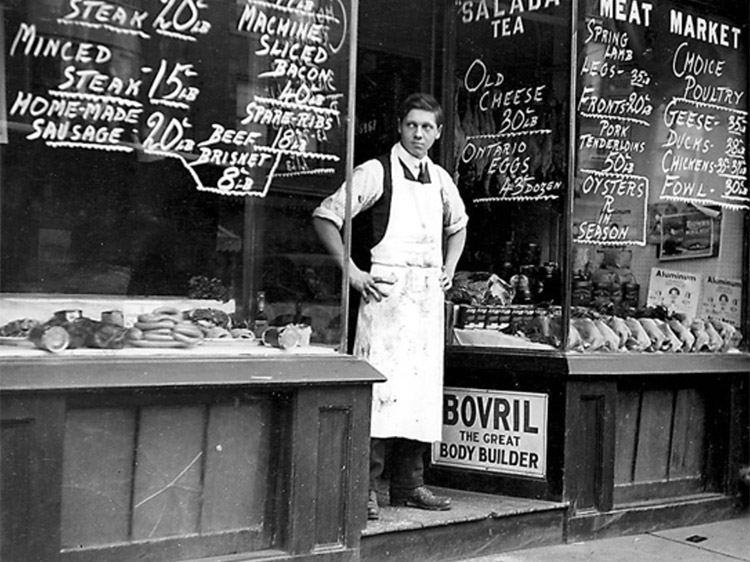

The empty scale in the above photo captures a rare moment of quiet on College Street. Normally busy and crowded, College Street was a scene of action and suspense when the Boyd Gang robbed the nearby Bank of Montreal at College and Manning Street in 1952.

In the 1950s, a heyday for organized crime in Canada, Toronto had their very own criminal gang: The Boyds, named after Edwin Alonso Boyd. Notorious for bank robbing, torrid love affairs, breaking out of prison, and, eventually, murder, they made newspaper and television headlines from 1951 to 1952.

* * *

The final days of the Boyd Gang began on March 6th, 1952, at the Bank of Montreal on College and Manning Street. Alerted to a midday robbery, two police officers stopped a black Mercury Monarch at College and Lansdowne. When officers Edmund Tong and Roy Perry left the police car, Steve Suchan opened fire on both of them. He hit Tong and grazed Perry's arm before peeling away in the car. Tong died in the hospital on March 12th, 1952.2

The manhunt that followed led police all the way to Montreal, where both Suchan and Jackson were arrested independently of one another after violent gunfights. Following a hunch, police arrested Boyd after his brother led them to his location. Yet once again, the prison time wouldn't stick. The four men, including Willie Jackson, who had been arrested earlier, escaped once again from Don Jail on Sept 8th, 1952. The resulting manhunt held media attention; a $26,000 reward (over $250,000 today, adjusted for inflation) was put up to help with their capture.3

The gang's freedom did not last long, as all four men were recaptured only a week later, and the trials began. Both Suchan and Jackson were tried for murder, and were hung in Don Jail on December 16th for the death of Edmund Tong.4 Boyd was sentenced to life in prison, but served parole and moved to the West Coast of Canada.5

While the Boyd Gang robbed banks all over Toronto, the College Street robbery would be the beginning of the end of a short but violent period in Toronto's history.

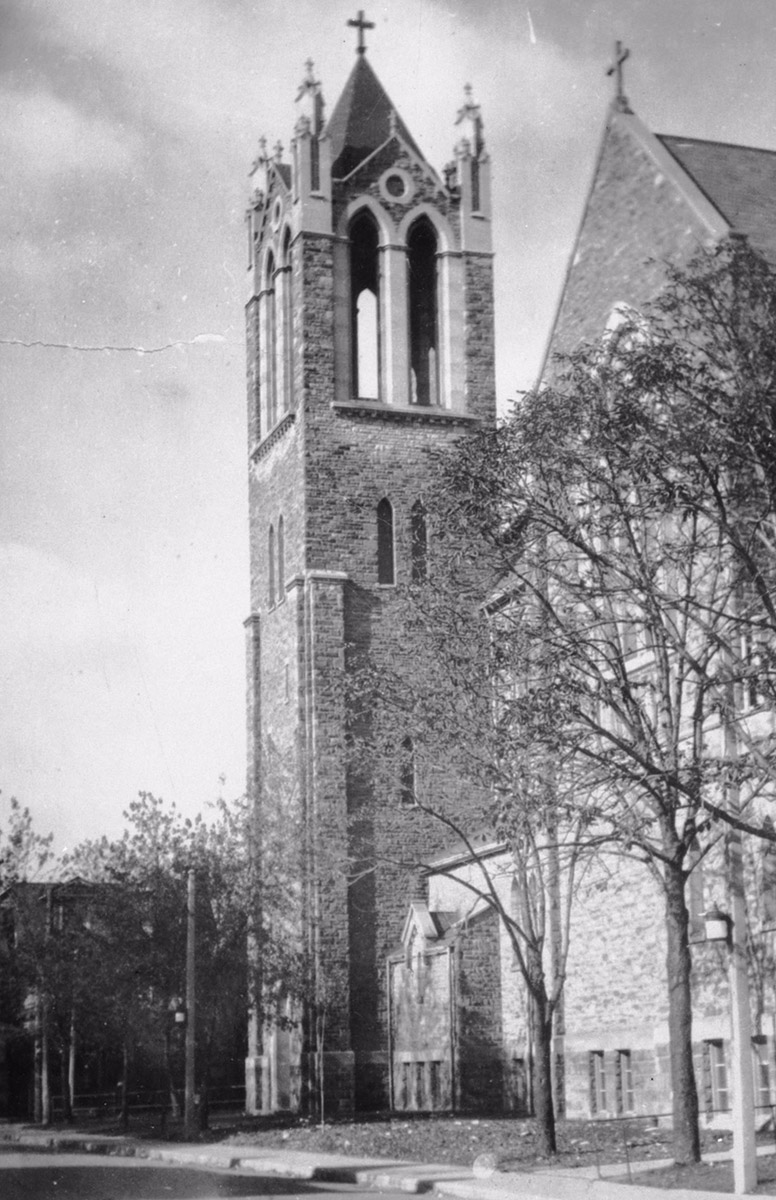

7. Portuguese Immigration

1910

The church in this photo is just one example of how College Street has adapted to serve its diverse community. Constructed in 1865 as a Baptist Church, the building presently houses the Portuguese 7th Day Adventist Church.

In the melting pot that makes up the fabric of Toronto, one of the relatively new additions is the Portuguese that have made College Street their home. While many of the immigration stories of Toronto began in the early part of the 20th century, immigrants from Portugal were only allowed into Canada in the 1950s, following an initiative by the Citizen and Immigration Department of the federal government.

* * *

By 1960, over 5,000 families had registered with the Portuguese Consulate, while another 1,000 were estimated to have not registered. Very quickly, whole families were coming over from Portugal rather than just young men. Success stories were seen in a variety of places, from the now extinct Lisbon Bakery that opened in the Kensington Market in 1960, to development of the Portuguese place of worship in front of you.

8. Italian Labour in Toronto

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 16, Series 71, Item 4055

1925

In the above photo, it is mostly Anglo Canadians who ride the streetcar, while today, College Street is a diverse neighbourhood made up of a multitude of communities.

When Italian immigrants came to Canada in search of work all throughout the 20th century, however, they were ostracized from Anglo Canadian places of employment and viewed as unskilled and grimy. In 1913, author Margaret Bell wrote a romanticized image of the street labourer: "The picks swing up, then down, then up again. Each swing is accompanied by some utterance, an unintelligible uttering or snatch of song. And you think of the Italian operas and the greatest singers of them."1

* * *

This pattern carried on throughout the pre-war period, whereby through community connections or family ties, new immigrants would move into a variety of industry-based work, needlework, or grocery ownership. During the second wave of immigration to Canada, newly landed Italians found themselves in much the same position as their earlier counterparts, seeking unskilled or low-paid piecemeal labour—with one major change. Children of immigrant parents would go onto apprenticeships and clerical work, often in their parents' stores.2

What was lost on many of Toronto's Anglo residents was the critical and important role that young Italian men played in the development of the city, often working dangerous occupations in atrocious conditions for meager pay.

Take the disaster at Hoggs Hollow in 1960, for instance. Five Italian 'sandhogs', as underground maintenance workers were called, were working underneath Yonge Street excavating a tunnel for a water main when the section they were working in collapsed. With no extra resuscitators, fire extinguishers, or even basic tools like flashlights, the five young men asphyxiated from carbon monoxide and drowned after a rising flood of water and mud prevented their rescue. With anachronistic safety standards that left 'sandhogs' in Industrial Revolution-era working conditions, the death of the five young men was a harsh reality check on the safety of workers, in particular immigrant workers, in Toronto. When a coroners' commission called the death preventable, Ontario changed its labour laws for the first time since 1920.4

The hard work of young immigrants has been instrumental in shaping Toronto into what it is today. In the case of Hoggs Hollow, the sacrifice of those young men has never been forgotten. Yet a city built through immigrant labour has not always been kind to those who made it what it is.

9. The Difficult Journey of Coming to Canada

1935

Captain's Barber Shop is one of many businesses that dotted the landscape of College Street prior to the 1950s, like the nearby Enzo's Barber Shop at College and Euclid.

For the first influx of Italian immigrants at the end of the 19th Century, the process of finding paid employment and making a home for themselves was a formidable task, one that seemed insurmountable. Many were coming to Canada with little more than a smattering of English and a connection to a family member who had come before. Some unskilled labourers had the support of a padroni, an organisation that helped bring them to Canada to work on farms.1

* * *

As Italians moved to College and Grace, what grew from a rapid migration became, by necessity, a focal community that catered to its own. As many of the men who came and went from their homeland to Canada and back needed places to work, rent, eat, and meet their other needs, small nuclei of businesses developed. A notice in a 1913 issue of Bollettino dell'emigrazione, an Italian newspaper, explained that "the majority of Italians are peasants who work as labourers, however, working 9 to 10 hours a day with average earnings of $1.75 to $2.25." Two years later, in the same journal, Girolamo Moroni reported that most Italians were "tailors, barbers, shoe repairmen and shoemakers, orchestra musicians, waiters, carpenters, shoeshiners, etc."3 Some of the earliest immigrants found work at Vincenzo Muto's tailor shop at the nearby corner of Grace and College. Many of the men who worked in the shop slept in living quarters on the second floor. Thus, business on College Street began to grow.

By the 1920s, businesses on College Street were thriving. W.G Smith noted in 1920 that the Italian immigrant was a master in the "green-grocery" fruit trades "to which he brought ingenuity, deftness, industry and business sagacity that are most praiseworthy."4 While early Italian immigrants worked in every business, grocers on College Street were a cornerstone of their community and their presence encouraged others to settle and take jobs nearby.

Like other "Little Italies" across North America, the networks and support systems found on College Street were not just nationally Italian, but also reflective of the places that the Italian families came from. Many of the immigrants from Italy came from towns and regions with their own distinct identities. The Italian greengrocers found in Toronto in the early 20th century, for example, were run by families from the city of Cosenza, who all utilized the same padroni and boarding house when first immigrating. Likewise, many of the families from the Molise region in Southern Italy lived near Grace Street in the early 20th century.5

The yearly pilgrimage from Italy to Canada and back was not only a difficult journey, but one that required not just ties to the home country but a strong community here. The padroni and the regional Italian identities that developed in Toronto from pockets of migration have given it a distinct identity.

10. College Street as Home

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1244, Item 7375

1944

From College Street, take a look down Manning Street - you’ll see that the street looks similar to how it did a century ago; many of the same houses line the street. Some have changed their look over time, but they are still here.

Manning Street is just one of many of the residential streets that line College and house the neighbourhood's residents, with a few interspersed businesses such as the former Lieberman's Pharmacy near Manning and College. The post-war immigration of Italians to Toronto created long-lasting change to the landscape of Little Italy. Cafes and bars were opening left and right, Johnny Lombardi was launching music, and the streets were becoming the Little Italy we see today.

* * *

That second boom, however, cemented how much College Street had become a home-away-from-Italy for many of its newer and older residents. An interview with a local man about immigrating to Canada in 1952 captured how College Street street was home to many in that period. "It was a different world altogether. It was cold. I stayed first on Brunswick Avenue and then on Clinton Street. My cousin was like a father for me. This other cousin, Joe, spotted the construction boots in my suitcase. I opened a suitcase because I brought a bottle of liquor for him from San Giorgio ... I never forgot his wife, Esperanza, who made a beautiful supper, everything was there on the table. There was steak, pasta, you name it." 2 In 1961, census documents stated that more than 16,000 Italian people lived in the area surrounding College Street, even as they had a greater diaspora than their earlier counterparts. And for many, the alternative to wage labour was to open a shop that catered to their own Italian communities; thus, the neighbourhoods of College Street bloomed.

11. Cultivating Italia and Recreating the Piazza

1960

This photo captures a quintessential moment in the history of Toronto's Little Italy: the crowd celebrating after the World Cup.

The booming of Italian culture on College Street was cemented after the 1950s, with the second wave of immigration and the rise of patio culture. Notable businesses in the area included Bar Italia and the nearby Cafe Diplomatico, as well as the now out of business Jam Company.

* * *

While both businesses listed no longer provide the fine goods that we see today in Little Italy, the article captures how important the later half of the 20th century was for Little Italy and the push to create and recreate Italian culture. One of the most critical components of this was the creation of cafe culture, with the opening of businesses like Bar Italia and Cafe Diplomatico. Unlike the Canadian version of a bar, Bar Diplomatico, as it was called when it first opened, specialized in espresso and lunch menus. These businesses were called bars for the Italian translation of 'cafe'. Bar Diplomatico had a wide patio where patrons could congregate and communicate with those walking down the street, so that people could stop and socialize. Despite the focus on food and espresso, the cafe also had a liquor licence.2

The liquor licence associated with an Italian cafe was notably Italian in nature, as in Italy, liquor is available in every cafe, and all cafes serve coffee well into the late hours. In Canada, serving liquor with coffee was something that had its roots on College Street, but didn't always sit well with Toronto authorities. In 1957, an Italian cafe owner was fined heavily for operating without a liquor licence. Buying bootlegged moonshine, cafe owners would often top up patron's coffees in the same way they would in the home country. The police's reaction to the cafe owner was a sore spot in the community, and spotlighted an anti-Italian sentiment that lingered in Toronto. 3

The creation of cafe culture in Little Italy in the later half of the 20th century filled an important absence that was notable for the Italian immigrants from the home country—the piazza. In Italian towns, both large and small, much of the real estate is centred around a piazza, a town square that is surrounded by open sidewalk cafes. Here, people can gather and sit, socializing and catching up on the daily news as they check in with their neighbours. In Italy, this is central to the maintenance of community, and it was notably absent in Canada. Yet with the opening of local Italian cafes, alongside a wide variety of Italian grocers, College Street had become its own piazza in a town far away. 4

12. The Jewish Community in College

ca. 1950s

Cohen's Fish Market was one of many Jewish owned and operated businesses that used to line College Street before many of them moved 'up the hill'.

Cohen's was known as a community landmark for its window signage: depending on which way you walked by, you would either see a sign in Hebrew or English, serving both communities. While it was named Little Italy and was home to many Italian immigrants, Jewish communities also grew up and prospered along College Street in the early 20th century.

* * *

At the turn of the 20th Century, the massive influx of Jewish immigrants, particularly from Russia, had begun to strain the limited resources that the immigrant communities had. Poverty was widespread in the Ward amongst Jewish families between 1901 and 1915, as the numbers of Jewish families grew exponentially. Many were alarmed by the ramshackle state of the homes they saw. When one mother arrived with her family in 1912 to join her seventeen-year-old son and “first saw the shabby house that would become her new home, she cried out ‘Feh! The pig sties in Konstantinov are nicer than this! This is why we gave up our house and everything we had? Tell me my son, is this the gan aiden [Garden of Eden] you wrote me about?’". 2

By 1933, nearly 50,000 Jewish immigrants lived in Toronto, with a significant number of them building homes and communities along College Street and Spadina, which was referred to as the heart of the Jewish community. Jewish businesses along College Street also flourished alongside the Italian ones.

That same year however, the College Street community, and in particular the Jewish immigrants that had made Little Italy their home, would face the growth of anti-semitism and right-wing facism in light of Hitler's rise to power in Germany. In Toronto, support for Hitler took the form of a swastika club run by young Anglo men from the surrounding neighbourhoods. These men took to wearing and displaying the swastika at local events. On the night of August 16th, 1933, the second in a two-series baseball game started at Christie Pits Park, located just up from College Street and Bathurst. When young Jewish men saw swastika club members raise the symbol on a painted blanket, they tried to grab and destroy the item, and a fight broke out. The riot soon spread to the neighbourhood and grew from support for both sides, with the Italians of College Street firmly on the side of their Jewish neighbours.

"While groups of Jewish and Gentile youths wielded fists and clubs in a series of violent scraps for possession of a white flag bearing a swastika symbol at Willowvale Park last night, a crowd of more than 10,000 citizens, excited by cries of 'Heil Hitler' became suddenly a disorderly mob and surged wildly about the park and surrounding streets, trying to gain a view of the actual combatants, which soon developed in violence and intensity of racial feeling into one of the worst free-for-alls ever seen in the city. Scores were injured, many requiring medical and hospital attention ... Heads were opened, eyes blackened and bodies thumped and battered as literally dozens of persons, young or old, many of them non-combatant spectators, were injured more or less seriously by a variety of ugly weapons in the hands of wild-eyed and irresponsible young hoodlums, both Jewish and Gentile."2

The Christie Pit riots betrayed the deeper anti-immigrant and anti-semetic sentiments that existed in Toronto's Anglo community. These feelings would only grow in the wake of World War II.

While anti-semitism would blossom and grow, and then change in 1955 with the election of Toronto's first Jewish mayor, College Street would remain home to a number of Jewish businesses and organisations. By the 1970s, however, many of the Jewish businesses had moved out of the community and 'up the hill', to neighbourhoods that showed significant promise. While largely gone, the sense of community and shared strife that marks the Jewish history on College Street remains.

13. Arts, Culture, and Radio on College Street

1940s

While businesses and restaurants have always been an important part of the College Street neighbourhood, the arts have also shaped the fabric of the community.

The nearby CHIN radio station, the Pylon theatre playing Italian movies, and the Lux Burlesque captured the Italianness and diversity of College Street. Johnny Lombardi, instrumental in playing multicultural music at CHIN, owned the nearby Lombardi Grocery, while the Monarch Tavern was a local watering hole.

* * *

Other notable arts venues along College Street included the nearby Lux Burlesque Theatre, which operated for a brief year, in 1961. Located nearby at College and Brunswick, the Lux Theatre was the first burlesque theatre to hold a Sunday matinee that featured a performer by the name of Cup Cake Cassidy. Photos from that day show a line-up around the block, as predominantly men gathered to see the Sunday matinee. Sadly, the theatre closed after a year, only to later run Greek tragedies.2

When talking about arts and culture in Little Italy, one cannot ignore the influence of Johnny Lombardi, and CHIN radio. Johnny Lombardi, the 'unofficial mayor' of “Little Italy” Toronto, had a significant influence on multicultural radio not just in Toronto but in all of Canada. Lombardi was born in 1915 in the Ward to Italian immigrant parents. Growing up, he learned to play the trumpet, and during his time in World War II, he played all throughout his service. When he returned to Canada, Lombardi opened Lombardi's Grocery, first located at Dundas and Manning, later at Clinton and College, and finally at College and Grace. Lombardi loved music, and was later responsible for a record store. In 1947, he purchased a one-hour slot at CHUM radio to play Italian music and advertise his grocery store.3 In 1966, he opened up CHIN radio, the first and only Multicultural station in Ontario, with offices located above his supermarket on College/Grace Street.

“I’ve always wanted a radio station,” Lombardi enthused in the studio over his College Street supermarket in the heart of Little Italy. “I was up at 6 a.m. to listen. I’m so excited, I feel six feet tall!”4 Lombardi is well known for being an important part of multicultural radio in Canada, and was awarded an Order of Canada in 1981 for his role. He is widely considered the father of Multicultural Broadcasting in Canada. Other notable businesses in the College Street art scene include Bar Italia, which was known for bringing in important jazz acts, and Sniderman's Music Hall, which eventually transformed into Sam the Music Man record stores. 5

14. Anti-Immigration Sentiment

1959

Throughout the 20th Century, College Street grew rapidly, as more and more businesses and restaurants were founded, with many still standing today. By the 1970s, College Street was renowned for its restaurants and cafes.

The hustle and bustle we see in this picture from 1959 would only grow in the later part of the 20th Century. Nearby businesses that have flourished include the Power Supermarket, the Standard Club, the Grace Meat Market, and the Health Bakery. However, the Italian community has not always been appreciated in Toronto.

* * *

In early 1900s Toronto, many of the city's Anglo views about immigrants were closely tied to the cleanliness of the Ward, and the slum-like settings that residents there lived in. An article in the Globe and Mail in 1904 by Emily Weaver refers to the Italians by their "hot southern blood and the too-ready knives of some immigrants." 1 Other views were based on the nature of the work that many of the young immigrant men undertook, such as on railways and or in skilled labour.

For the Jewish and Italian communities of College Street, there was a large uptick in racism and xenophobia with the start of World War II in 1939. While the Jewish faced growing anti-semitism and nazism, the Italian community were labelled facist sympathizers. When Mussolini declared his alliance with Hitler, 200 Italian-Canadians were arrested and interned while under investigation for any facist leanings. 2 Italian and Jewish businesses took a sharp turn downward.

In the post-war period, Italian immigrants still felt the 'otherness' that had marked the previous years, but with the addition of the second wave of immigration. As Italian immigrants came in greater numbers to Toronto, there was an equal rise in nativist backlash.

An excerpt from Robert Allen's 1964 article in Macleans paints a picture of how Anglo Toronto saw their Italian neighbours on College Street:

"Here one finds people from Naples and Palermo looking at snails in grocery stores, listening to Italian records, and enjoying the novel life of a community of Italian movies, espresso bars, pizza parlours, pointed shoes, short jackets, Sicilian shawls and such vitality that going home to, say, North Toronto, is like entering a decadent suburb ... Many welcome this exotic tidal wave that has given texture to the city and suddenly made Toronto as self-consciously cosmopolitan as a teenager who has just discovered beer. Others look at these changes dourly, still call Italians "Eyetalians" and misuse the word "ethnic" to mean exactly what they used to mean when they said "foreigner." A few think vaguely of Little Italy as a cluster of grocery stores in an old part of town but many think of it as a tough neighborhood of ward heelers, underground societies, and Tammany hall politics, where Italian youths pinch girls' behinds, and more mature citizens, when they aren't eating spaghetti, are stealing jobs from Canadians." 3 Another source of hatred and vitriol for the Italian immigrants of Toronto was their working class status. One man remembers his discomfort at riding the streetcar in dirty work boots in the 1960s: "In a strange country with a different language. We were the working people. Even riding the streetcar was not that simple. They would humiliate you with remarks and insults—you know, 'dirty wop' [or] 'go back to Italy.'"3

While the job-stealing mentality of many Toronto residents likely remains, there is also evidence of Toronto's acceptance of their Italian neighbours. The embrace of Toronto's Italian community can now be seen in the attendance of the Good Friday Procession, of Johnny Lombardi's multicultural radio, and the maintenance of Little Italy itself.

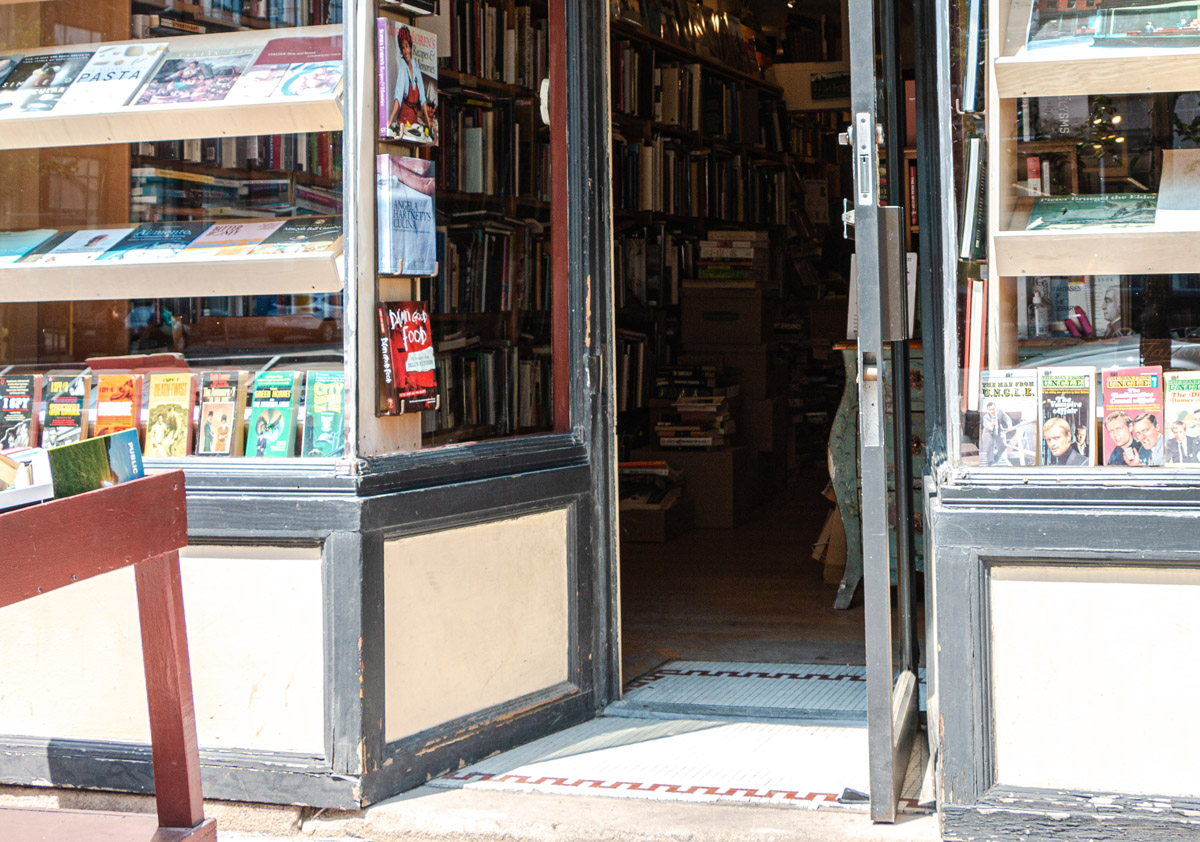

15. Little Italy Today

ca. 1950s

While no longer Sniderman's Music Hall, the building in front of you still stands, even though most of its neighbours are gone. There is no longer a line for records, and the nearby Capp's Drug Mart has vanished.

The neighbourhood has grown and shrunk yet again, with businesses such as the nearby Il Gatto Nero and Porco Brothers Grocery Mart coming and then going, while others like the Sicillian Sidewalk Cafe and the nearby Vivoli restaurant have stood the test of time. Others have evolved through the years, such as the West End Veterans Club that became a Polish Hall, and then a Mrs. Stokes Candy Bar that today is the home of Dolce Gelato. Yet College Street is still an arts focused multicultural community with a history of immigration, culture, change, struggle and triumph. Little Italy was shaped by the people who have called this place home, and the past lingers.

* * *

While Little Italy has changed since its early days, one element has stayed throughout: its sense of community. For the Italian immigrants, in the first wave and the next, Little Italy became not only a spot for espresso, but the place for making and cementing community ties. Business owners, arts and culture, and organisations run by community leaders had a hand not only in creating Little Italy, but making it a place for anyone to come and find home. The notions of family, home, and community have been present throughout the history of Little Italy, and survive strong today. While the future is decidedly uncertain, one thing is sure: a sense of community is thriving in Little Italy. As Kent Nussey says "it is a real place, a real neighbourhood; it feels like home."1

Endnotes

1. The Early Days of College Street and the University of Toronto

1. http://torontoplaques.com/Pages/St_Hildas_College.html, accessed Sept. 26, 2020.

2. Klerck, D. D., & Paina, C. (2006). College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance strip. Toronto, Mansfield Press.

3. Myrvold, Barbara. Historical Walking Tour of Kensington Market and College Street. Toronto Public Library Board, 1992.

2. College Street's Early Days

1. Hess, H. & Gay AbbateThe Globe and Mail 1998, Oldest black church destroyed: Police suspect arson as fire guts Shaw Street landmark, damages two others, Toronto, Ont.

2. https://www.salemchapelbmechurch.ca/index.html

3. AN, OLD RESIDENT. "COLLEGE-STREET AND OUR THREE PARKS." The Globe (1844-1936), Jul 25, 1878.

4. Klerck, D. D., & Paina, C. 2006. College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance strip. Toronto, Mansfield Press.pp 112-113.

3. Traveling to Canada

1. E. Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988.

2. Lorinc, J., 1963, McClelland, M., 1951, Scheinberg, E., 1964 & Taylor, T. 2015, The Ward: the life and loss of Toronto's first immigrant neighbourhood, First edn, Coach House Books, Toronto, ON. pp. 102

3. E. Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988.

4. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

4. Religion in the College Street Community

1. Zucchi, J.; E. Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935. 9780773561687. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988

2. Stanger-Ross, J., 2006. An inviting parish: Community without locality in postwar Italian Toronto. Canadian Historical Review. P. 387

3. https://www.catholicregister.org/features/featureseries/item/24817-historic-images-of-good-friday-procession-portray-a-community-of-faith

5. The Ward

1. "THE HOUSING PROBLEM." The Globe (1844-1936), Dec 14, 1906.

2.Globe and Mail, 1908. As presented in Lorinc, J., 1963, McClelland, M., 1951, Scheinberg, E., 1964 & Taylor, T. 2015, The Ward: the life and loss of Toronto's first immigrant neighbourhood, First edn, Coach House Books, Toronto, ON. pp 16.

3. The Globe. 1913, June 12. Toronto Determines to Wipe Out Slums.

6. The Boyd Gang's Legacy on College Street

1."After 3 Years-Graduation: Sentence Boyd and Gang Today." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 16, 1952.

2. "Boyd Gang Box Score." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 09, 1952.

3. "Wanted, Dead Or Alive: $26,000 IN REWARDS Armed-to-Teeth Police Search for Boyd Gang." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Sep 09, 1952.

4. "2 Hanged in Canada for Killing Detective." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Dec 17, 1952.

5. "Edwin Boyd Given Life, W. Jackson 20 Years." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 17, 1952.

7. Portuguese Immigration

1. Kritzwiser, K. (1960, Apr 30). Portugal adds its flavor to the city's potpourri. The Globe and Mail (1936-2017).

2. Klerck, D. D., & Paina, C. (2006). College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance strip. Toronto, Mansfield Press.pp 112-113.

8. Italian Labour in Toronto

1. E. Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988. 72

2. Ibid.

3. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992. Pp 107.

4. Ghafour, H. March 2000. Survivor Recalls Hogs Hollow Disaster. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/survivor-recalls-hoggs-hollow-disaster/article18421680/

9. The Difficult Journey of Coming to Canada

1. Zucchi, J. 1988, Italians in Toronto: development of a national identity, 1875-1935, McGill-Queen's University Press, Kingston, Ont.

2. Ibid.

3. Zucchi, J. 1988, Italians in Toronto: development of a national identity, 1875-1935, McGill-Queen's University Press, Kingston, Ont. pp. 77

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

10. College Street as Home

1. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

2. DeMaria Harney, Nicholas. Eh, Paesan!: Being Italian in Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

11. Cultivating Italia and Recreating the Piazza

1. Jukes, M. 1960, Mar 03. The shopping basket: Italian groceries bring wider horizons. The Globe and Mail (1936-2017)

2. De Klerck, D. and Paina, C., 2006. College Street-Little Italy Toronto’s Renaissance Strip.

3. Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

4. Chawla, K. Ranger, C. 2016. An Investigation into Toronto’s Little Italy and its Gastronomic Roots. In Lobalsoma, T. editor, Gastronomy, Culture, and the Arts: A Scholarly Exchange of Epic Proportions, Conference Proceedings. University of Toronto, Mississauga.

12. The Jewish Community in College

1. Tulchinsky, G.J., 1993. Taking root: The origins of the Canadian Jewish community. UPNE.

2. Lipinsky, Jack. Imposing Their Will: An Organisational History of Jewish Toronto, 1933-1948.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011. p. 17.

2. Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933.

13. Arts, Culture, and Radio on College Street

1. De Klerck, D. and Paina, C., 2006. College Street-Little Italy Toronto’s Renaissance Strip.

2. Ibid.

3. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/johnny-lombardi

4. The Toronto Star. June 16, 2016. Once Upon a City. CHIN Picnic Prepares for Another 50 Years. https://www.thestar.com/yourtoronto/once-upon-a-city-archives/2016/06/16/once-upon-a-city-chin-picnic-prepares-for-another-50-years.html, accessed August 15/2020.

5. De Klerck, D. and Paina, C., 2006. College Street-Little Italy Toronto’s Renaissance Strip.

14. Anti-Immigration Sentiment

1. E. Zucchi, John. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988.

2. Lacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

3. Ibid.

15. Little Italy Today

1. Klerck, D. D., & Paina, C. (2006). College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance strip. Toronto, Mansfield Press.pp 112-113.

Bibliography

"2 Hanged in Canada for Killing Detective." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Dec 17, 1952.

"After 3 Years-Graduation: Sentence Boyd and Gang Today." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 16, 1952.

An Old Resident. "College Street and our Three Parks." The Globe (1844-1936), Jul 25, 1878. Online.

"Boyd Gang Box Score." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 09, 1952.

Chawla, K. Ranger, C. An Investigation into Toronto’s Little Italy and its Gastronomic Roots. In Lobalsoma, T. editor, Gastronomy, Culture, and the Arts: A Scholarly Exchange of Epic Proportions, Conference Proceedings. Mississauga: University of Toronto, 2016.

"Edwin Boyd Given Life, W. Jackson 20 Years." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Oct 17, 1952.

Ghafour, H. March "Survivor Recalls Hogs Hollow Disaster." The Globe and Mail. 2000. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/survivor-recalls-hoggs-hollow-disaster/article18421680/

Harney, Nicholas DeMaria. Eh, Paesan!: Being Italian in Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

Hess, H. & Gay Abbate. "Oldest black church destroyed: Police suspect arson as fire guts Shaw Street landmark, damages two others." The Globe and Mail. 1998. Toronto. Online.

Iacovetta, Franca. Such Hardworking People: Italian Immigrants in Postwar Toronto. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

Jackson, Kip. "Johnny Lombardi." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Sept. 4, 2008. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/johnny-lombardi

Jukes, M. The shopping basket: Italian groceries bring wider horizons. The Globe and Mail (1936-2017). 1960.

Klerck, D. D., & Paina, C. College Street, Little Italy: Toronto's Renaissance strip. Toronto: Mansfield Press, 2006.

Kritzwiser, K. (1960, Apr 30). Portugal adds its flavor to the city's potpourri. The Globe and Mail (1936-2017).

Lipinsky, Jack. Imposing Their Will: An Organisational History of Jewish Toronto, 1933-1948.. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011.

Lorinc, J. 1963, McClelland, M., 1951, Scheinberg, E., 1964 & Taylor, T. 2015. The Ward: the life and loss of Toronto's first immigrant neighbourhood, First edn, Coach House Books, Toronto.

Myrvold, Barbara. Historical Walking Tour of Kensington Market and College Street. Toronto: Public Library Board, 1992.

Stanger-Ross, J., An inviting parish: Community without locality in postwar Italian Toronto. Toronto: Canadian Historical Review, 2006.

"The Housing Problem." The Globe (1844-1936), Dec 14, 1906. Online.

"Toronto Determines to Wipe Out Slums." The Globe. June 12, 1913.

Toronto Daily Star, August 17, 1933.

Tulchinsky, G.J. Taking root: The origins of the Canadian Jewish community. UPNE, 1993.

"Wanted, Dead Or Alive: $26,000 IN REWARDS Armed-to-Teeth Police Search for Boyd Gang." The Globe and Mail (1936-2016), Sep 09, 1952.

Zucchi, John E. Italians in Toronto: Development of a National Identity, 1875-1935. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1988.