A Black community has been present in the London region since the early 1820s. In 1829, a group of families arrived at Port Stanley, on their way to an area north of London where they would create a new settlement. Originally from Cincinnati, they had left from Sandusky, one of eight Underground Railway (UGRR) terminals on Lake Erie. The UGRR was a network of escape routes and sanctuaries manned by abolitionists, Quakers and the formerly enslaved, who provided food, lodging, directions and transportation to runaways. Port Stanley and Port Burwell in Elgin County would each become a point of arrival for both free Blacks and enslaved persons fleeing their "owners,” particularly after 1850 when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. The Act allowed "owners” to come into the northern states and retrieve runaways still considered property under the law. It also required state and local authorities to assist in their return. The fugitives were often followed into Canada by those seeking to return them to enslavement, though few were successfully taken back. At Port Burwell, the immigrants were met by a stagecoach which followed the Plank Road north to Ingersoll where they found work. Many helped build the Great Western Railway in the 1850s. Most of those who arrived at Port Stanley went on to London in search of jobs. The Black population in London by the mid-1850s was around 350, many of whom worked as tradesmen or owned businesses. One Black congregation was able to open a new brick church in 1869 which is still in use today. There was discrimination, however, particularly in the public schools which Blacks were discouraged from attending. Plans to build a separate school, however, did not proceed as the Black population rapidly declined at the end of the Civil War when many went home. Only after WWI, did the Black community begin to grow again, rising to about 250 people by 1930. This was the estimate made by the Canadian League for the Advancement of Coloured People, an organization founded in London in 1924 by James F. Jenkins, an immigrant from Georgia. His daughter Kathleen (later Kay Livingstone) was instrumental in the formation, in 1973, of the Congress of Black Women of Canada. Today, there are more than 11,000 residents of African origin residing in the London area who come from a diverse number of African cultures and countries including Sudanese, South Sudan, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Ethiopia, among others.

This project was funded by the Canada Healthy Communities Initiative in partnership with several of the area’s museums, archives and public historians.

We respectfully acknowledge that the land on which we gather is the traditional territory of the Attawandaron, Anishinaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and Lunaapeewak peoples who have longstanding relationships to the land, water and region of southwestern Ontario. The local First Nation communities of this area include Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, Oneida Nation of the Thames, and Munsee-Delaware Nation. Additionally, there is a growing urban Indigenous population who make the City of London home. We value the significant historical and contemporary contributions of local and regional First Nations of Turtle Island (North America).

Explore

Middlesex-Elgin Counties

Stories

Shadrach Martin

c. 1908

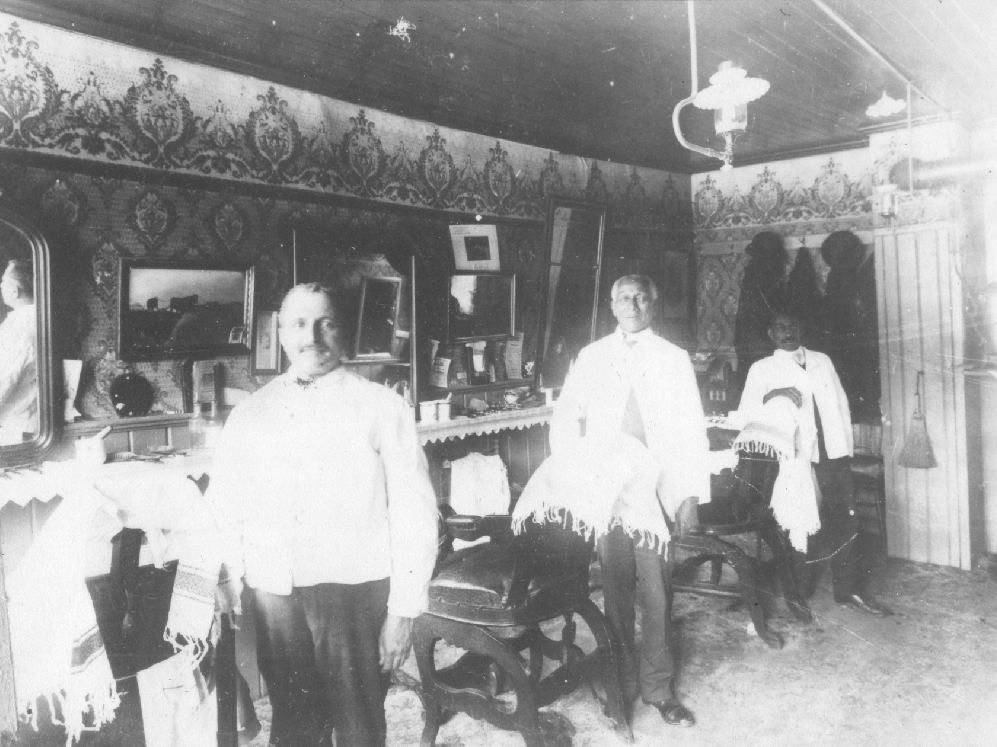

George Taylor's barber shop at 145 King Street. Left to right: Will Taylor, Shadrach Martin and Thomas Logan.

Shadrach Martin, known as "Shack,” was born in Nashville in 1833. He said his father was a free man and his mother was a former slave, whose freedom had been purchased by her future husband. By age 11, he was working on a steamboat as a cabin boy. At age 13, he became apprenticed to a barber in Memphis and later moved to Cincinnati, where he stayed until he moved to London in 1854. In the depression of the late 1850s, Shack returned to the United States, where he obtained work as a barber on a Mississippi steamboat. At the beginning of the American Civil War, he was encouraged by one of his regular customers, a Union gunboat captain, to enlist in the navy. He was accepted and served for two years on the captain’s gunboat. Receiving his honourable discharge in May, 1863, he returned to London where he became one of the best-known barbers in the city. As early as 1868, Shadrack Martin and James Worthington were operating a barber shop together in the Tecumseh House Hotel. Then the best hotel in the city, it was located near the Great Western Railway station on York Street, where the Via station is today. George Taylor and his partner, William Newman, had a shop that same year in Strong’s Hotel which was on Dundas Street, just east of Richmond.

Barbering was a traditional Black occupation and, in these years, they would have served an all-white clientele. Martin’s customers included London’s long-time MP Sir John Carling and John Labatt the brewery owner.

Wilberforce Settlement Mural

2020

This is the Wilberforce Settlement Mural located at 180 Main Street, Lucan.

Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Colborne’s response to a request from Cincinnati Black leaders to establish a settlement in Upper Canada, 1829:

"Tell the republicans on your side of the line that we royalists do not know men by their colour. Should you come to us, you will be entitled to all the privileges of the rest of His Majesty's Subjects."

Wilberforce, founded in 1829, was one of the earliest settlements attempted by African-Americans in Upper Canada. It was initiated by residents of Cincinnati, Ohio, a free state which was located across the Ohio River from Kentucky, a slave state. Both Black refugees from the south and Free Blacks were arriving in the city seeking jobs, joined by a growing number of Irish immigrants. By 1829 when rioting broke out there were 25,000 people in the city, most seeking work and housing. In June, 1829, to put the Black population at a disadvantage, the city voted to enforce the "Black Law,” a statute that had been on the books for over 25 years, requiring Blacks put up a bond of $500.00 immediately or face expulsion. Then, in August, violence erupted, when over 200 whites attacked the Black neighbourhoods in an attempt to force their departure. Unable to pay the bond and with the threat of violence close at hand, many Blacks sought new homes.

A colonization society was formed and Upper Canada was decided on as a potential place of safety. Two representatives met personally with the Lt-Gov. of the day, Sir John Colborne, who enthusiastically welcomed them. They had come at a time when a large tract of land, including what is now Huron County, had just been opened up for settlement. It is possible that Colborne directed them to this land which had been put under the management of a private company called the Canada Company. Seeking to escape city life, they agreed to purchase 4000 acres in Biddulph Township, then part of the tract, at a total cost of $6000.00.

Within weeks, as many as 1500 Blacks departed the city, most making their way to Canada where they dispersed to various locations. 18 families were known to have crossed from Sandusky to Port Stanley, but only 5 or 6 of them walked the additional 35 miles to the township which had just been surveyed. Funding the immense purchase had proved impossible and only at the last minute did Quakers in Ohio and Indiana provide funds to purchase 800 acres located along the main settlement road (now Highway 4). Arriving in the Upper Canada wilderness must have posed a challenge for the settlers. Yet they persevered and were soon joined by several families from the Boston area. By 1832 the settlement was composed of log houses, crops, livestock, saw mills, stores, and a school.

The settlement came to be led by Austin Steward a successful grocer in Rochester who had escaped slavery himself. He heard about the settlement at a convention in Philadelphia he attended in 1830. After an initial visit, he sold his business and brought his family to live there in 1831. He stayed for six years during which time he served as the president of the management board for the settlement. It was Steward who named the settlement after a prominent British abolitionist, William Wilberforce.

The first few years were tough for the settlement. It was unable to grow because the Canada Company was unwilling to sell additional land to prospective settlers fearing it would deter white settlement. As well, Irish immigrants were arriving in increasing numbers creating the potential for tension. Also, many of the initial settlers were finding the gruelling work of creating farms out of a wilderness overwhelming and decided to move on. A population which had reached about 70 by the mid-1830s began to dwindle over the next several years. Steward himself left in 1837. The settlement later contained the small village of Marysville. It would grow rapidly once the Grand Trunk Railway came through in 1859 and was thereafter renamed Lucan.

* * *

A colonization society was formed and Upper Canada was decided on as a potential place of safety. Two representatives met personally with the Lt-Gov. of the day, Sir John Colborne, who enthusiastically welcomed them. They had come at a time when a large tract of land, including what is now Huron County, had just been opened up for settlement. It is possible that Colborne directed them to this land which had been put under the management of a private company called the Canada Company. Seeking to escape city life, they agreed to purchase 4000 acres in Biddulph Township, then part of the tract, at a total cost of $6000.00.

Within weeks, as many as 1500 Blacks departed the city, most making their way to Canada where they dispersed to various locations. 18 families were known to have crossed from Sandusky to Port Stanley, but only 5 or 6 of them walked the additional 35 miles to the township which had just been surveyed. Funding the immense purchase had proved impossible and only at the last minute did Quakers in Ohio and Indiana provide funds to purchase 800 acres located along the main settlement road (now Highway 4). Arriving in the Upper Canada wilderness must have posed a challenge for the settlers. Yet they persevered and were soon joined by several families from the Boston area. By 1832 the settlement was composed of log houses, crops, livestock, saw mills, stores, and a school.

The settlement came to be led by Austin Steward a successful grocer in Rochester who had escaped slavery himself. He heard about the settlement at a convention in Philadelphia he attended in 1830. After an initial visit, he sold his business and brought his family to live there in 1831. He stayed for six years during which time he served as the president of the management board for the settlement. It was Steward who named the settlement after a prominent British abolitionist, William Wilberforce.

The first few years were tough for the settlement. It was unable to grow because the Canada Company was unwilling to sell additional land to prospective settlers fearing it would deter white settlement. As well, Irish immigrants were arriving in increasing numbers creating the potential for tension. Also, many of the initial settlers were finding the gruelling work of creating farms out of a wilderness overwhelming and decided to move on. A population which had reached about 70 by the mid-1830s began to dwindle over the next several years. Seward himself left in 1837. The settlement later contained the small village of Marysville. It would grow rapidly once the Grand Trunk Railway came through in 1859 and was thereafter renamed Lucan.

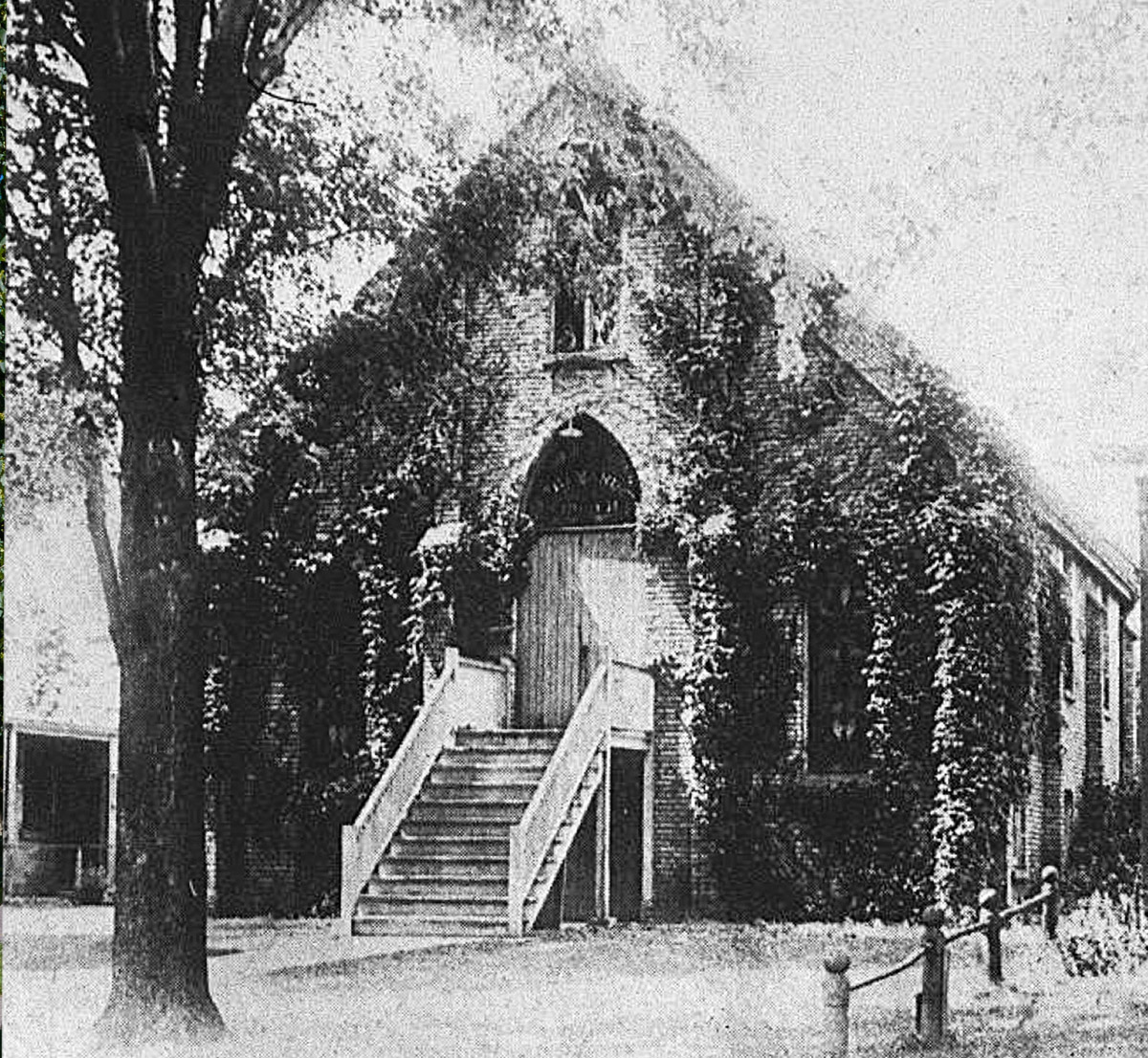

African Methodist Episcopal

The African Methodist Episcopal Church at 275 Thames Street.

Many of Upper Canada’s earliest Black settlers were members of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church which formed an Upper Canada Conference in 1840. In the early 1840s, a London Circuit of the AME was formed and around 1848 a church was built on Thames Street, the centre of early Black settlement in London.

At this time, there were about 300 Black residents in London supporting a total of three churches - two Methodist and one Baptist. This population continued to increase particularly after the passage in the United States of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. The Act was one reason that caused the Canadian AME churches to break away from their American parent in 1856 and form the British Methodist Episcopal (BME) Church.

In the early 1860s, London’s BME minister, Rev. Lewis C. Chambers, reported on the success he’d had in establishing a temperance society, encouraging Sabbath schools, and in the growth of the congregation. In fact, several years later they purchased a lot on Grey Street, in an area where many in the congregation now lived. Here, they built a new church, in 1868, naming it Beth Emanuel. The little wooden chapel was then sold and for many years was used as a house.

When the original church building on Thames Street was threatened with demolition in 2013, Beth Emanuel offered to provide it with a new home. Hundreds of private citizens assisted by the City of London contributed to the relocation of the chapel to a lot next to Beth Emanuel. At the time of writing (2022), the BMEC has offered the chapel to the Fanshawe Pioneer Village. If sufficient funds are raised this historic building might soon find a new home there to tell the history of Black settlement in the area, North American enslavement, and the Underground Railroad.

Unable to proceed with the project, the former church was later offered to Fanshawe Pioneer Village, London’s living history museum. After extensive fundraising, the building was moved to the Village in 2022 where it was restored and opened in 2023.

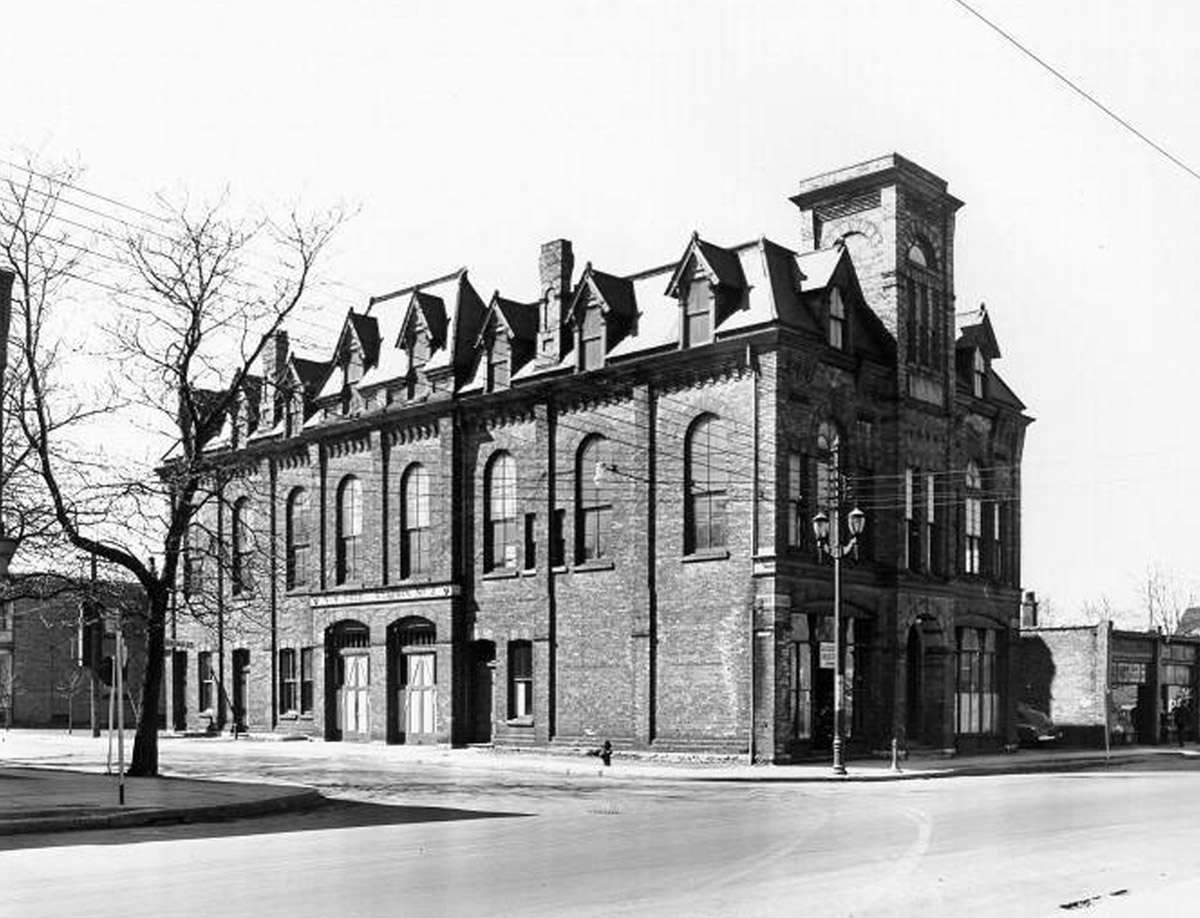

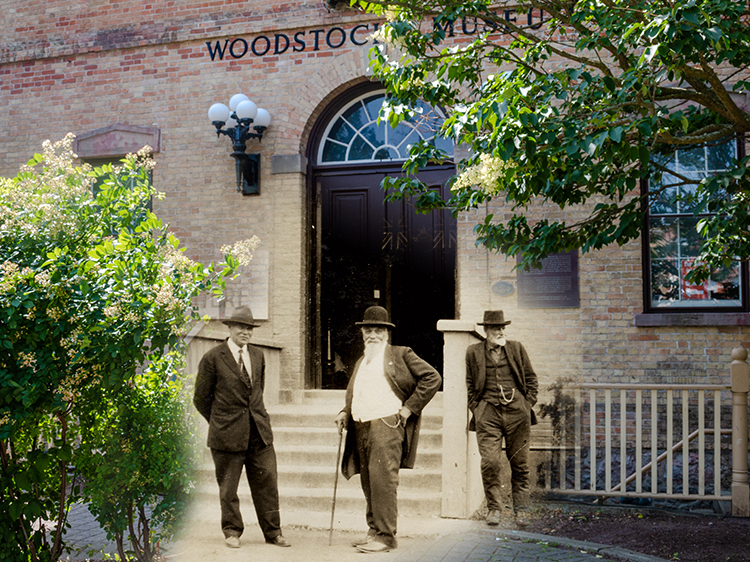

Aeolian Hall

c. 1940

This was the site of the first convention of the Canadian League for the Advancement of Coloured People in 1927.

It "is not what we were yesterday, not yet is it what we are today that gives us so much hope, but it is, according to the handwriting on the wall, what we shall be tomorrow. And thus we have chosen our name: The Dawn of Tomorrow.”

- Robert Paris Edwards, Associate Editor, The Dawn of Tomorrow, July 14, 1923

Following WWI, the Black community in London began slowly to grow again, rising to about 250 people by 1930. This was the estimate made by the Canadian League for the Advancement of Coloured People, an organization founded in London in 1924. The League, whose leadership included both Black and White Londoners, was organized "to improve the condition of the coloured people of Canada,” particularly through the provision of educational opportunities for the young.

The founding of the League was mainly the work of James F. Jenkins, a Georgia native who had been a resident of London since 1907. The League had an official newspaper, The Dawn of Tomorrow, which Jenkins had founded in 1923. The Dawn carried news of interest to the Black community, much of it originating in the United States. It also brought the Black communities in other Ontario towns and cities closer together by listing their activities in columns of social and church notices. It was also Jenkins’s intention to "chronicle any achievements of (the) people and any advance that would spur young people to self effort.”

James Jenkins died suddenly following surgery in 1931. His widow Christina (later Mrs. Frank Howson), who had, from the beginning, supported and encouraged her husband’s work, carried on the publication of The Dawn of Tomorrow with the help of her large family. The success of the newspaper, at first a weekly and then a monthly publication, is a testament to the dedication of the Jenkins family. At its height, about 1971, it had a total circulation of 48,000, and 21,000 subscribers in various parts of the world.

Selected editions are available on-line at the The Dawn of Tomorrow's community memory project created by students at the Huron University College.

Full files of the newspaper are at the Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library and the Archives at Western University.

Program for the first convention of the Canadian League for the Advancement of Coloured People, 1927 is available online through the New York Public Library.

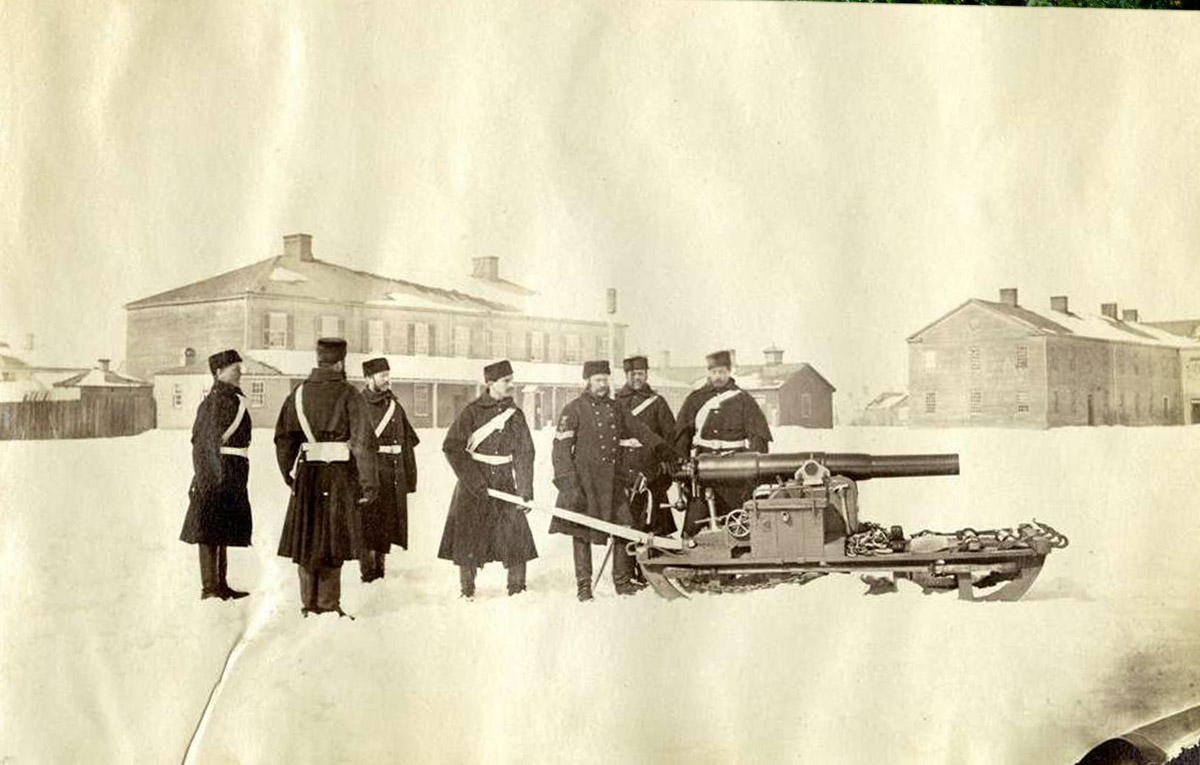

Colonial Church & School Society

c. 1867

An artillery gun sleigh, drawn up in front of the British Army barracks in what is now Victoria Park.

Following the Rebellion of 1837, regiments of the British Army were posted to various places in the Canadas. In London, a base covering a large area was established on the north edge of town, part of which would later become Victoria Park. The barracks, which usually housed part of a regiment, were almost empty during the 1853-56 Crimean War and immediately thereafter.

It was during this time that the Colonial Church and School Society was offered part of the Royal Artillery barracks for use as a school. The Society had been organized to minister to settlers in far-flung reaches of the colonies. One section was set up to provide schooling to those in the colonies who had been freed by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and to the formerly enslaved who had escaped to Canada. They located their Canada West school in London, where the rapidly growing Black population had reached an estimated 350 by 1855. There was also support there from the Anglican clergy and laity. During this period, few Black children were attending the common schools because of the vociferous opposition to their presence from white parents. This prejudice often extended to the teaching staff.

The school was led by the Rev. M. M. Dillon, a member of the Society in England and a proponent of integrating the Society’s schools. He had volunteered to lead the mission to Canada West himself. Prominent white families impressed with the discipline and a religiously-infused curriculum also sent their children to the school. In June of 1855, Benjamin Drew, an American abolitionist then touring Canada West, found 175 students at the school, 50 of whom were Black. The total number of school-aged children in the Black community was 96 in 1862. Rev. Dillon left London in 1856 due to ill-health and, losing its driving force, the school closed two years later.

Not everyone supported the initiative. Mary Ann Shadd, editor of the Provincial Freeman newspaper in Chatham, called it misguided charity. She argued that Blacks, who paid taxes to support the public schools, should have equal access to them. However, it was very difficult to overcome the widespread white opposition to integrated schools. In fact, in 1863, the school board decided to build a separate school for Black students. This did not happen, possibly because of the decline in the Black population following the end of the Civil War.

Beth Emanuel Church

c. 1926

Beth Emanuel British Methodist Episcopal Church, 430 Grey Street.

The new brick church for the Black Methodist community, dedicated May 16, 1869, had been built to accommodate 200 people. Early preachers included Walter Hawkins (1882), born a slave in Maryland and later a BME Bishop, and Thomas Clement Oliver (1890-91), who had been active in the Underground Railroad. Eventually most pastors and worshippers were Canadian-born, augmented in the twentieth century by immigrants from the Caribbean.

In addition to revenues from the collection plate, the congregation raised funds by hosting an annual southern fried chicken supper, organizing a Christmas bazaar, and holding tag days. The congregation boasted social and outreach groups that responded to a variety of Christian needs: the Brotherhood for men, the Stewardess Board for women, a choir ably led for many years by the noted singer Paul Lewis, a baseball team for boys, and the Women’s Home and Foreign Missionary Society.

Frequently, the congregations of Beth Emanuel and nearby Hill Street Baptist Church met for both celebrations and services. Their combined Sunday schools took the London and Port Stanley Railway to Port Stanley for an annual picnic. Attendance began to decline in the second half of the twentieth century, reaching a low of 30 members in 1969, although friends and adherents increased that number somewhat. In 1991 a fire, resulting in $300,000 damage, caused services to be held in the basement until repairs were completed, with many London churches donating to the project.

In recent decades, Beth Emanuel has evolved into a church providing social outreach to individuals and families in need. Its mother church, formerly on Thames Street, was a sanctuary to those fleeing slavery.

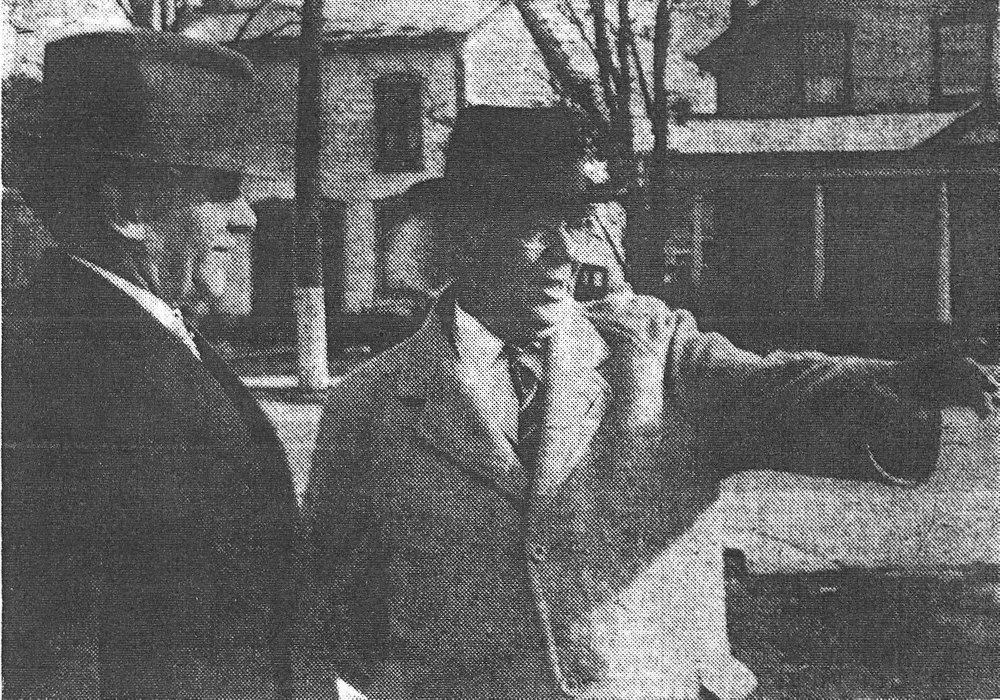

Richard B. Harrison

1934

Richard Berry Harrison (at right, with Mayor George Wenige) points to the location of his former boyhood home on Wellington Street near the river.

Richard B. Harrison (1864-1935) was a London-born actor, whose parents, both former slaves, escaped to Canada in the 1850s. The family remained in London until 1880 when they moved to Detroit, where Harrison trained as an elocutionist. His stage work, which took him all over Canada and the United States, was comprised of dramatic monologues, as well as readings of poetry and literature.

The role that would make him famous was that of "De Lawd” in a play called the Green Pastures. Seen today as somewhat patronizing and fostering African-American stereotypes, the play at the time was well received. It won the Pulitzer Prize for author Marc Connolly in 1931 the same year that Harrison received the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, presented annually for outstanding achievement by a Black American. Harrison toured with a production of the Green Pastures to over 200 cities including London, his hometown.

In 2019, London playwright and actor Jeff Culbert, created a one-man theatre piece entitled "Elocution: The Life of Richard Berry Harrison” starring legendary Canadian actor Walter Borden. It can be heard at www.jeffculbert.ca.

Kay Livingstone

1971

Kay Livingstone, left, and her sister Mrs. Evelyn Johnson in front of Beth Emanuel Church.

Born in 1918, Kay was one of eight children born to James and Christina Jenkins. Her father was a juvenile court judge in London, and was largely responsible for the founding of the Canadian League for the Advancement of Coloured People, in London, in 1924, as a way "to improve the condition of the coloured people of Canada.” The League had an official newspaper, The Dawn of Tomorrow, which Jenkins had founded in 1923. The Dawn brought the Black communities in Ontario towns and cities closer together by listing their activities in columns of social and church notices.

James Jenkins died suddenly following surgery in 1931. His widow Christina (later Mrs. Frank Howson), who had, from the beginning, supported and encouraged her husband’s work, carried on the publication of The Dawn of Tomorrow with the help of her family.

With her parents as an inspiration Kay spent much of her life founding and leading a number of organizations involved in fighting racial discrimination and giving a voice to the Black community’s interests and concerns.

From a young age, she developed an interest in the performing arts, studying music in Toronto and Ottawa. In 1942, she married George Livingstone, and they moved to Toronto where they raised their children. Not confined to the family home, Livingstone maintained a brilliant acting career. She was called "one of Canada’s leading Black actresses” during this time, performing in both amateur and professional productions and having a career in radio.

In the 1950s, as the civil rights movement gained momentum in the United States, Livingstone’s thirst for action and change transformed her social gatherings into a mutual aid association called the Canadian Negro Women’s Association. She served as its first president, from 1951 to 1953, and remained an active member afterward. Livingstone provided the organization’s vision to promote the pride and the contributions of the African Canadian community. Through this organization, Livingstone initiated and organized the first National Congress of Black Women, held in Toronto in April 1973. This filled a void on the political spectrum, as African Canadian women’s concerns were lesser priorities for both the Black civil rights movement and the second wave feminists. Given the event’s success, other conventions followed in cities across Canada, which led to the creation of the permanent organization that exists today.

She worked to involve the nation in a dialogue on the role of women and African-Canadians as a consultant for the Privy Council of Canada. In 1975, during the United Nation’s International Women’s Year, she travelled the country with a plan to organize a national conference of women who belong to a visible minority. Livingstone died suddenly in the summer of 1975, leaving the Black community in a state of shock. Her story is one of a fighter who worked tirelessly for the African-Canadian community and for the betterment of society.

(Reproduced from the designation of Kathleen 'Kay' Livingstone as a National Historic Person by the Government of Canada, 2011).

Lloyd Graves

Ingersoll Cheese and Agricultural Museum

c. 1900

Lloyd Graves and his wife Amanda in front of their home in Mount Salem.

One of the few stories of fugitive slaves arriving in Port Stanley is that of Lloyd Graves. He escaped his "master” in Kentucky around 1854 after hearing that he was to be "sold south” meaning to a cotton or sugar plantation in the deep south which promised a life of great hardship. He came north with another fugitive on horses stolen from the master. They were taken across the Ohio River to Cincinnati and hidden in the attic of a house. They continued north to Cleveland, travelling part of the way concealed in a wagon. Here they were put onto a steamer which crossed the lake to Port Stanley.

Graves soon found his way to St. Thomas where he worked for a merchant named Thomas Lindop as a teamster. He eventually earned enough to buy a small farm of several acres on the second concession of Malahide Township. In 1868, he married Amanda Irons, the daughter of a fugitive slave and his wife. At one time her parents had lived on River Road, just east of St. Thomas.

The Graves eventually moved into the village of Mount Salem bringing this small house with them, to which they later built an addition. They had a family of 12 children. Mr. Graves died in 1927 at the age of 105. Mrs. Graves was 99 when she passed away in 1939.

Home of Peter Butler III

Lucan Area Heritage and Donnelly Museum

c. 1975

Home of Peter Butler III, 158 Princess Street, Lucan.

Peter Butler III’s grandfather was one of the original Wilberforce settlers arriving in the 1830s from the Boston area. He was married to one of three sisters from the Quacum family, women of Indigenous descent each of whom came to the settlement with their husband and children. All three men would have a role in directing the operation of the settlement.

Peter Butler took a circuitous route to get to Biddulph Township working a as caulker in shipyards in Port Dover and Port Stanley along the way. He had escaped slavery in Baltimore where he had been born in 1797, by going to sea for 7 years. On his return, he married Salome Quacum in Marshfield on the coast of Massachusetts, south of Boston. They later moved to Boston, a centre of abolitionist activity and probably heard about the Wilberforce settlement there.

Peter cleared and farmed Lot 5 on the main road between London and Goderich (now Highway 4). Clearing that road was one of the requirements for owning land in the settlement. Today about one half of the town of Lucan is located on what was Lot 5. The town’s establishment and growth were largely the result of the building of the Grand Trunk Railway in 1859, which ran right through Peter’s lot.

These three families were among the few that had remained in the settlement by the end of the 1830s. Clearing the land was hard, progress was slow and some gave up after a few years. Both Peter and his son, Peter II, served the community as healers with their knowledge of herbal remedies.

The third-generation Peter Butler, born in 1859, also farmed and in 1883 became a county constable. He later joined the Ontario Provincial Police, becoming the first Black officer to be hired by the force. Descendants of the family can still be found in Lucan and area.

Port Burwell

c. 1855

Bridge Street, looking east towards Otter Creek in Port Burwell.

Port Burwell and Port Stanley received a number of free Black and formerly enslaved immigrants in the years before 1865. Few left a record of any kind so it is difficult to gauge the number that actually arrived on these shores.

Port Burwell was the landing place for many formerly enslaved persons who crossed Lake Erie looking for freedom in Canada. Here, they travelled inland on what is known today as Plank Road (County Road 19), a name it acquired in the 1850s when it was literally paved with wooden planks. In 1849, legislation was passed giving private companies the power to lease public roads and collect tolls. In exchange the roads were to be maintained to certain standards. The best surface obtainable then was plank. Bayham Township was in the midst of a timber boom in the 1850s. Millions of feet of sawn lumber were shipped out every year and it would have been relatively easy to surface a road with planks all the way to Ingersoll.

From the port, fugitives took a stage coach as far inland as Ingersoll. The stage was often driven by Harvey C. Jackson, a well-connected abolitionist. Jackson served as a guide for John Brown when he visited this area in the 1850s, recruiting for his raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Most of the newly arrived fugitives travelled north on the stage where many found jobs cutting wood for the building of the Great Western Railway. As many as 2500 African-Americans were at work on the railways in this part of Canada in 1851. The 1861 census recorded 149 Blacks as resident in Ingersoll, the most common stopping point, but it is likely lower than the actual number.

Port Stanley

McIntosh Gallery, Western University

c. 1840s

Elgin County became both a home and a landing point for many free Blacks and formerly enslaved persons. A relatively short trip across Lake Erie brought freedom for many. Port Burwell and Port Stanley received a number of Black immigrants in the years before 1865. Few left a record of any kind so it is difficult to gauge the number that actually arrived on these shores.

At least 18 families fleeing riots and repression in Cincinnati landed at Port Stanley in 1829, on their way to establish a settlement north of London near what is now Lucan. Known as the Wilberforce Settlement, it grew to about 70 people and then declined to just a few families. Its leader Austin Steward, an escaped slave who had later prospered in Rochester, also arrived in Port Stanley in 1831 before heading north.

The narrative of one couple, known only as Peter and Polly, is found in the memoirs of Alexander Ross, a Canadian abolitionist and an agent of the Underground Railway (UGRR). He was responsible for bringing 30 slaves to freedom from the US.

Just before the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Ross went to Harrodsburg, located near the middle of Kentucky, then a slave state, pretending to look for a farm to buy in the area. He was given a guide, an enslaved man, who told Ross his wife had been sold to a hotel-keeper in Covington, a town across the Ohio River from Ohio, a free state. He asked Ross for help to escape and to rescue his wife. He sent the man to Cincinnati, providing him with the names of contacts who would hide him once he got there. He then found the man’s wife in Covington and took her away in a row boat to the Ohio side of the river. Ross then departed for Cleveland to make arrangements to get them to Canada. Meanwhile other members of the UGRR shipped the couple to Cleveland in a box marked "hardware and dry goods.” Ross met the train and brought the couple to the docks where they were stowed away on a steam boat by the captain and taken to Port Stanley. From there Ross took the couple to London and found them work.