Partner City

Essex County

Gateway to Freedom

Essex County lies at the extreme southwestern tip of Ontario, facing the United States across the fast-flowing Detroit River. This strategic location made Essex County a critical crossing point in the Underground Railroad for enslaved people seeking their freedom in Canada. From the early decades of the 19th century, Black communities of escaped slaves established vibrant, tight-knit communities in Essex County, and worked tirelessly to aid their brethren who remained in bondage in America. The town of Sandwich was located just opposite Detroit (Sandwich is now a neighbourhood in Windsor), and the Sandwich First Baptist Church became a central node in the Railroad, receiving, sheltering, and assisting new arrivals to Canada, and the scene of many tearful reunifications. The church is today a National Historic Site. The town of Amherstburg, to the south, also became a critical station in the Underground Railroad. As the legendary American abolitionist said, Amherstburg was "the great landing place, the principal terminus of the underground railroad of the west." From 1850, it is estimated that 30 escaped slaves made the crossing to Amherstburg every day. All across Essex County there are key sites in the remarkable history of the Underground Railroad that have been highlighted as part of this project. Visit some of these story locations to learn the stories of courage and resilience that shaped and continue to shape this part of Ontario.

This project was funded by the Canada Healthy Communities Initiative in partnership with several of the area’s museums, archives and public historians.

We acknowledge that the land on which Essex County is located is the traditional territory of the Three Fires Confederacy of First Nations, which includes the Ojibwa, the Odawa, and the Potawatomie. We honour all First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples and their valuable past and present contributions to this land.

Explore

Essex County

Stories

Amherstburg Freedom Museum

The Amherstburg Freedom Museum welcomes all people of all ages to experience the history of the Underground Railroad. The Amherstburg Freedom Museum is a curated archive that preserves and shares Amherstburg’s stories of the Underground Railroad, and the compassion and solidarity it took to make this network possible. The site includes Nazrey AME Church, National Historic Site and a terminus of the Underground Railroad, and the Taylor Log Cabin from the same period that looks like the occupants just stepped out for a moment. It is entirely appropriate, and even necessary, that the Museum was established in Amherstburg. Amherstburg meant freedom, as the Canadian destination for many Freedom Seekers escaping enslavement in the United States. The Museum is uniquely situated to resource a profound history, steeped in its surroundings, to further extend public knowledge and enjoyment.

Henry & Mary Bibb Plaque

Henry and Mary Bibb both began their lives in the United States, but under markedly different circumstances. Henry Walton Bibb (1815-54) was born in Kentucky to an enslaved mother Mildred Jackson and an enslaver father Senator John Bibb. He grew up with the brutality of being enslaved, made many attempts at escape, and finally reached Detroit in 1840. He soon became a well-known anti-slavery orator and writer.

Mary Elizabeth Bibb (1820-77) was raised by free Black parents in a Quaker community in Rhode Island. She became a teacher after graduating from the Massachusetts State Normal School in 1843. The pair met at an abolitionist meeting in New York in 1847 and were married the following year in Ohio.

In 1849, Henry published his autobiography Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave Written by Himself. In 1850, when the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in the United States both formerly enslaved persons and persons born free were in danger of being forcibly enslaved. With its passing, the couple moved to Sandwich (now part of Windsor). There, they founded a school for Black children where Mary taught. The couple also started a newspaper called Voice of the Fugitive which was the first newspaper in Ontario to be published by persons of African descent.

In Sandwich, the Bibbs provided many freedom seekers with food, clothing and assistance towards finding housing and employment. They were instrumental in the success of the Refugee Home Society which helped many formerly enslaved persons to purchase a home, land or a farm in Essex County.

See the The Voice of the Fugitive newspaper archives here.

Jackson Park Bandshell

For many years, Windsor citizens, some of whose ancestors had arrived from the U.S. on the Underground Railroad, celebrated Emancipation Day, which marks the day, August 1, 1834, on which slavery was abolished in the British Empire. In 1932, the Black community decided that they wanted to do something bigger and what became the “Greatest Freedom Show on Earth” was born.

At their peak in the 1950s and 1960s, the city’s Emancipation Day festivities stretched over several days and drew thousands of people from across North America to the city’s Jackson Park venue. Motown stars, like Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder and the Temptations, crossed the Detroit River to perform at the park.

* * *

Exterior causes, like the death of long-time organizer Walter Perry, resistance from the City of Windsor who wanted to create their own festival (Freedom Festival) to replace the emancipation celebrations, and the Detroit uprising in 1967 all contributed to the decline of the large-scale emancipation celebrations in Windsor. Despite the decline in the larger celebrations, Emancipation Day continues to be celebrated not only in Essex County but all over the country.

Watch this trailer for Mr Emancipation: The Walter Perry Story.

John Freeman Walls Historic Site & Underground Railroad Museum

At the entrance to the John Freeman Walls Historic Site and Underground Railroad Museum, there's a historic plaque that reads; In 1846 John Freeman Walls a fugitive slave from North Carolina built this log cabin on land purchased from the Refugee Home Society. This organization was founded by the abolitionist Henry Bibb, published of the Voice Of The Fugitive, and the famous Josiah Henson. The cabin subsequently served as a terminal of the Underground Railroad and the first meeting place of the Puce Baptist Church. Although many former slaves returned to the United States following the American civil war, Walls and his family chose to remain in Canada. The story of their struggles, forms the basis of the book "The Road That Led To Somewhere" by Dr. Bryan Walls erected by Proverbs Heritage Organization with the assistance of Maidstone Township and the ministry of culture and recreation.

McDougall Street Corridor

Windsor, like most major cities across Canada during the twentieth century, was home to a dynamic Black community located in the metropolitan core. Situated to the east of the Downtown commercial district, the McDougall Street Corridor was a mostly self-sufficient African Canadian community bound loosely by Riverside Drive East, Goyeau Street, Giles Street East, and Howard Avenue.

Aptly named for the heavy concentration of Black families along one of Windsor’s oldest streets, this historic neighbourhood emerged during the mid-nineteenth century as African American freedom seekers and free people of colour crossed the Detroit River in search of refuge from enslavement and oppression.

* * *

After the conclusion of the American Civil War brought the Underground Railroad era to an end, Windsor’s Black population continued to increase as families and individuals of African descent from rural areas of Southwestern Ontario moved into the Corridor, seeking employment.

Residents founded churches, businesses, social clubs, halls, and a credit union. This thriving community found creative ways to combat the discrimination they faced as a people, while providing services they were often denied elsewhere. The Walker House Hotel provided Black Canadians and Americans with safe lodgings as Windsor’s premier Black-owned hotel. The Mercer Street School allowed Black educators and students to thrive. Houses of worship fostered the development of social and activist organizations while attending to the community’s spiritual needs.

By 1941, Windsor’s Black population numbered more than one thousand. The community was extremely close-knit: many families in the area were related or connected through marriage. The neighbourhood served as a safe space within a city that was not always accommodating or kind to those of African descent.

However, the neighbourhood also served as a reminder of Black Windsorites’ second-class status. Housing segregation persisted until the 1960s, with few neighbourhoods beyond the McDougall Street Corridor allowing Black residents to rent or purchase homes. While residents spent decades advocating for an end to housing discrimination, these policies had long-lasting ramifications, including housing shortages for Black residents.

A 1957 survey conducted by the Windsor Interracial Council recorded approximately 250 Black families living within the Corridor. The same year, the City of Windsor took the first steps towards an aggressive urban renewal program. Across North America, there were attempts to raze areas that were deemed “blighted” or “rundown,” often uprooting racialized communities in the process. Windsor was no exception.

Windsor’s urban renewal policies destroyed historic churches, social halls, and multigenerational homes in the name of progress and modernization. Century-old buildings constructed by freedom seekers and their descendants disappeared from Windsor’s landscape, forgotten by almost everyone but the Black community.

Learn more about the McDougall Corridor.

Puce First Baptist Church

The origins of First Baptist Church go back to the 1840s, when Black settlers from the United States began to form a farming community in this area. Their numbers increased during the 1850s when the Refugee Home Society purchased lands along the Puce River to sell to freedom seekers from the American South. Religion played an important role in community life. At first Baptists and Methodists worshipped in the same building, but by the early 1860s they had their own churches. This church built in 1964, replaced a frame church that had served the Baptist congregation since 1871. It stands today as a symbol of the cultural and spiritual continuity of the Black community at Puce.

Irene Moore Davis, “Canadian Black Settlements in the Detroit River Region,” in A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland.

S.S. #11 Colchester Township South

School Section #11 was a rural school built in the early 20th century in a mainly Black school section. As with most “one-room” schools in the province, all grades from one to eight were taught together. It was one of several schools in Essex and Kent that remained under the control of separate boards of trustees elected in predominantly Black areas. Legislation allowing for separate white and Black schools in Canada West (Ontario) was passed in the 1850s, a time when large numbers of formerly enslaved persons sought refuge in southern Ontario. White residents in most districts refused to send their children to integrated schools, so the government was left with little choice but to allow Black persons to organize their own schools. Predominantly Black school sections were often not as well off as the neighbouring white sections and so their schools were often underfunded. As late as the 1960s, this legislation was still on the books in Ontario.

Over 50 students were still attending S.S. #11 in the early 1960s when other one-room schools in the township began to be closed. This period, known as consolidation, saw one-room schools close all over Ontario and the students bussed to a central school in each township. At first it appeared that S.S. #11 would be left out of the process. However, the parents, with the help of the South Essex Citizens’ Advancement Association, led by George McCurdy Jr., brought their case to the township board which also received a visit from then Minister of Education Bill Davis. The board agreed to send the students to the new consolidated school in Harrow which would be opening in September, 1965, along with school’s two teachers, and S.S. #11 was finally closed.

Learn more from this article in Professionally Speaking on Ontario's Last Segregated School.

Learn more from this article in TVO Today.

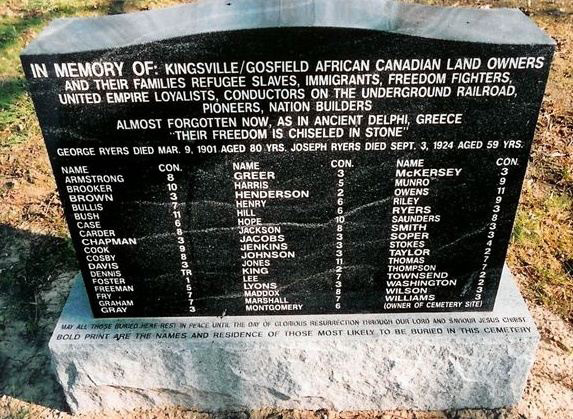

Salem Cemetery

This cemetery is all that remains of a Black settlement once located near the hamlet of Salem (sometimes called New Salem) which was centred around Division Road and what is now Road 3 West. A number of Black families, many of whom had escaped slavery, took up residence in the area establishing a Baptist church known as Shiloh, which once stood on Road 3 West, not far from this location.

In 1837, the land for this cemetery was purchased by John W. Williams, the first Black landowner in Gosfield, which has since been amalgamated into the Town of Kingsville. Williams purchased the property from Reverend Richard Herrington, a preacher who brought the Baptist faith to this area. Much of the history of this early Black settlement is unknown. This sacred ground is the only known African Canadian cemetery in the former Township of Gosfield.

This cemetery was designated under the Ontario Heritage Act in 2005, the year a monument listing the names of the area’s Black settlers was unveiled on the site.

Learn more from the United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada.

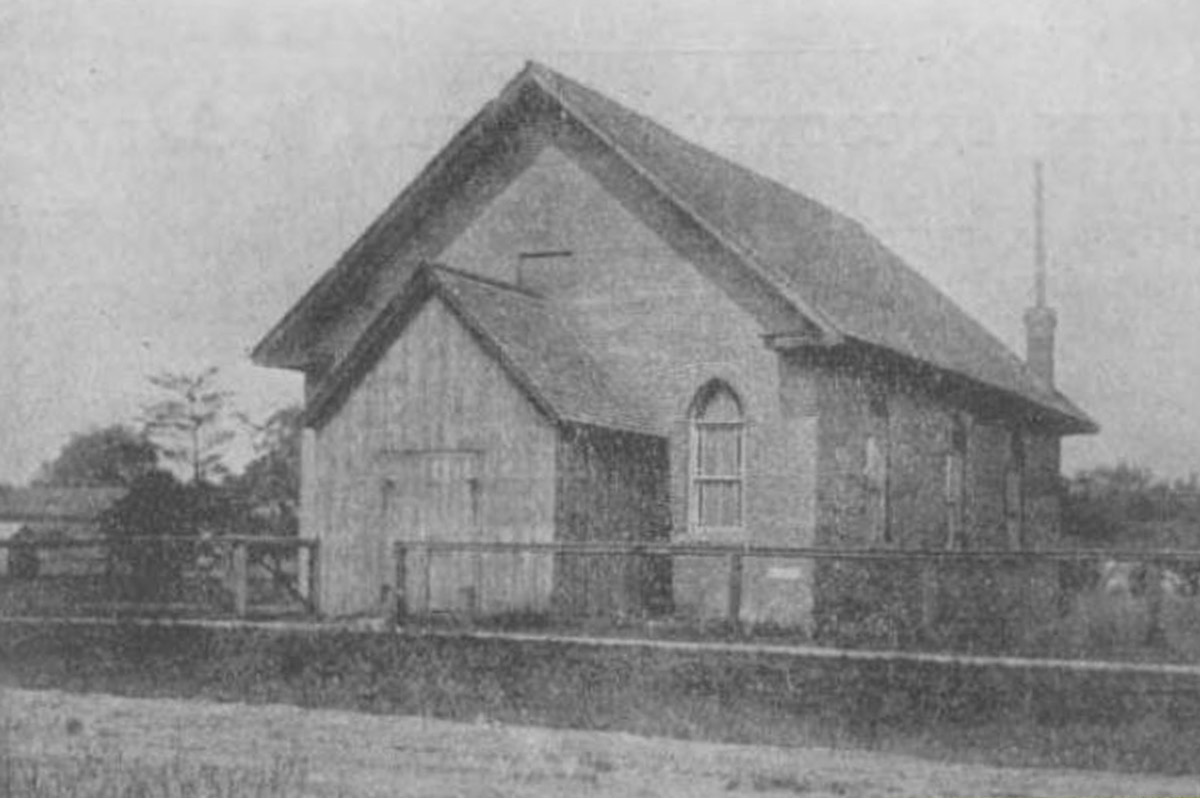

Sandwich First Baptist Church

ca. 1909

Erected in 1851 on land donated by the Crown, the Sandwich First Baptist Church (a National Historic Site) represents the once numerous Black border-town churches which were built to serve the rapidly increasing numbers of Underground Railroad settlers. This church received, sheltered, and assisted many of these new arrivals. All members were required to aid in its construction by giving donations or making bricks. It replaced a log cabin on Hill Street in Olde Sandwich Towne whose use as a Black church dated back to the early 1820s.

A focal point for many local anti-slavery activities, the Sandwich First Baptist Church stands as an important symbol of that struggle. When a bounty hunter was seen in the area, a bell was rung and every person who heard the ringing of the bell picked up a bell and began to ring it so that those who had escaped from the South would have time to hide in a designated spot in the church. The pastor would lock the door at the hearing of the bell. When all the formerly enslaved people were hidden away he would instruct his church to start singing "There’s a Stranger at the Door" and the church doors would be opened. Unable to find whoever they were looking for; the bounty hunter would leave empty handed.

Learn more at the University of Windsor's educational portal The North was Our Canaan: Exploring Sandwich Town's Underground Railroad History.

Read this history of Sandwich First Baptist Church in the Walkerville Times.

Smith Black Cemetery

Beginning in the 1830s, at least 30 families fleeing enslavement and racial oppression in the United States settled in the Banwell Road area in Sandwich East. They had the opportunity to purchase land through two Black-organized land settlement programs – the Colored Industrial Society (a mission of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Sandwich East) and the Refugee Home Society (administered by Black abolitionists Henry and Mary Bibb). Freedom and land ownership meant self-determination and financial security. Settlers purchased 10- or 25-acre parcels of land on which to build homes and farms. The A.M.E. church held 25 acres in trust to construct a church and a school – and for a burial ground at the site, namely, the Smith family cemetery – located here. These families created a strong sense of community by establishing institutions and advocating for social justice. The Banwell Road area Black settlement contributed to the history, economy and culture of the region, and paved the way for their descendants to live fulfilled, free lives.

Learn more from Ontario Heritage Trust.

Tower of Freedom Monument

From the early 19th century until the American Civil War, settlements along the Detroit and Niagara rivers were important terminals of the Underground Railroad. White and black abolitionists formed a heroic network dedicated to helping free and enslaved African Americans find freedom from oppression. By 1861, some 30,000 freedom seekers resided in what is now Ontario, after secretly travelling north from slave states like Kentucky and Virginia. Some returned south after the outbreak of the Civil War, but many remained, helping to forge the modern Canadian identity.

The Tower of Freedom, created by sculptor Ed Dwight, honours the flight of the freedom seekers along the Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad is bi-nationally commemorated by two monuments, representing its final stops.

The Detroit monument, located in Hart Plaza, depicts the Gateway to Freedom and features a bronze sculpture of six formerly enslaved persons about to leave for Canada. The monument acknowledges many people in Detroit and their participation in the Underground Railroad movement. The Windsor counterpart depicts their arrival into Canada and their overwhelming emotion upon encountering freedom.