Walking Tour

Toronto's First Steps

The People and Ideas that Shaped Toronto's First Century

Andrew Farris

Toronto Public Library -341687

Who built this city? What were they like? Why did they build it here? On this walking tour we will learn about Toronto's humble beginnings. We will journey along Toronto's former waterfront and through the site of the tiny settlement of York, which was first established here in the 1790s. Next, we'll visit the former site of the cramped tenement slums where many of Toronto's first immigrant communities settled in the mid-1800s, and then we will end our journey in the business district when Toronto stood on the cusp of the Industrial Revolution.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

1. Before the City

Toronto Public Library E 1-33b

1930

Right now, you are standing in front of Union Station in the heart of Canada’s biggest metropolis. Try to picture a time when all of this wasn’t here - it is pretty difficult, isn’t it? Yet, Toronto has only existed for a little over 200 years. The First Peoples have lived here for over 11,000 year. To put it into perspective, that is 400 generations of people, each with their own stories to tell and experiences to share. Sadly, many of these stories have been lost to history.

For a long time, the history of Toronto's First Peoples was neglected or ignored. However, a renewed focus on their oral traditions along with ongoing archaeological studies across the region are beginning to tell us much about what Toronto must have been like in the time before the city, and what the people who lived here were like.

* * *

Over the millennia that followed, the climate warmed and the lake's level rose, reaching its current level approximately 2,000 years ago. Fishing became increasingly important in the way of life of these first peoples, and technologies such as bows and pottery were introduced (most likely via trade). The populations remained small, and it is estimated that 1,500 years ago (500 CE), the entire population of southern Ontario was only around 10,000. The area around Toronto was inhabited by the Iroquois-speaking Wendat, and there were about 500 from each living on the banks of the rivers Don and Humber.1

It is around this time that southern Ontario started to be incorporated into the vast trade network that exchanged goods and ideas between First Peoples from across North America. Important crops like maize (corn), squash, tobacco, and beans were introduced from Mexico and the southern United States, and the people of this region gradually became farmers.

The shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture is a revolutionary transition in every society and Southern Ontario was no different. Farming meant that the food supply became more reliable and plentiful, which led to population growth, and increased cultural complexity. By 1300 CE, most people had given up their nomadic lifestyles and began to live in longhouses in semi-permanent villages. More mouths to feed increased competition for resources and land, and this likely led to warfare and raiding.

Many of these villages studied by archaeologists, such as the 15th Century Parsons site just south of York University, were sited on easily defended hilltops and surrounded by palisades. The bands began joining together into confederacies to trade and aid each other when attacked.

From the 1300s to the 1500s most of the Wendat peoples living around Toronto relocated north to join the Huron Confederacy. This was done for military reasons--their fierce rivals the Six Nations Iroquois moved into the region afterwards--or perhaps because the fishing was much better around Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. Nevertheless the Wendat maintained close ties to the region, and used a well-established trade route (also known as a portage route) from Lake Simcoe to the mouth of the Humber River, now in downtown Toronto.

Those fishing opportunities might be where the name 'Toronto' originated. The Hurons with whom the Wendat confederated with called the channel from Lake Simcoe to Lake Couchiching "tkaronto." In the Mohawk language this means "where there are trees standing in the water," which is a reference to poles staked into the riverbed to create fish weirs (a structure made of, in this case, wood, to direct fish to a specific area in the river). It appears that this name then lent itself to the portage route to Lake Ontario, which became known as the Toronto Passage.2

When French fur traders began penetrating the region in the mid-1600s, they used the Toronto Passage to reach the Hurons. Their maps labelled the entire region between Lake Simcoe and Lake Ontario as 'Toronto'. The route became so popular that in the 1700s they established several small forts near the mouth of the Humber, one of which was called Fort Toronto.

The French were mostly interested in fur trading, and made little effort to settle the area. So it remained until Britain took control of Canada from the French during the Seven Years’ War and the French forts in this region were abandoned. The American Revolution that followed, would initiate the next phase of Toronto's story.

2. The Loyalists

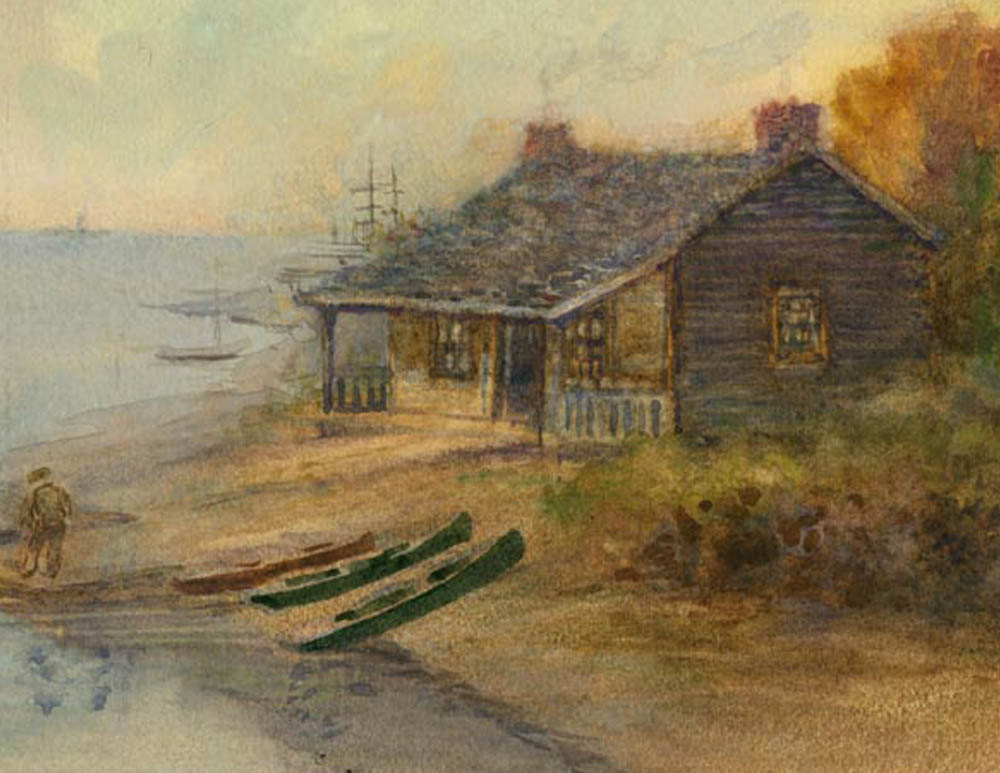

Toronto Public Library JRR 504 Cab

1800s

This watercolour painting shows the home of Michael Masterson at the foot of Bay Street. Back then, Lake Ontario's shoreline went all the way up to Front Street (hence the name). It has been pushed back 500 metres as Toronto has grown.

Masterson was a Loyalist who fled the United States in the 1780s and moved to the new province of Upper Canada, and settled at the little village of York that was established on this spot in 1793. The Loyalists were the first large group of European settlers in the province, and the British government hoped their presence would make the Americans think twice about invading Canada again.

* * *

19,000 of them volunteered to fight for Britain against the patriots, leading some historians to conclude that the American Revolution was more a civil war than a war of national liberation.2 3

When Britain lost the war and with it, some of her most prosperous colonies, it was nothing short of a catastrophe. The defeat was made all the more bitter because the British could--and probably should--have won if their generals and admirals had performed better at a number of turning points.4

Britain also felt they owed a debt of gratitude for the Loyalists who had lost so much fighting for the King. It was a hostile time for the Loyalists after the war in the new United States, and they were often threatened with loss of property, status, or even mob violence. Promised land and compensation by the British Parliament, some 100,000 of them voted with their feet and decided to emigrate in the 1780s.5

Where could these people settle?

The one silver lining in the Revolutionary War provided a solution: the British had defeated a bungled American invasion of Quebec in 1775, allowing them to hold on to Canada. As the British themselves had only conquered Canada from the French 20 years earlier, most of the settlers in Quebec and Nova Scotia were French farmers who were felt to be of dubious loyalty to the Crown. As for modern Ontario there was practically no British or French settlement at all outside the few fur trading forts.

If the British were to defend Canada, what more reliable subjects to do it than the United Empire Loyalists? It was decided to grant land in Upper Canada to the Loyalists who had fought for Britain, and 7,500 settled in southern Ontario.6 This was the first large European settlement in Ontario, and the region was organized into the new colony of Upper Canada in 1791.

These Loyalist settlers would play a pivotal role in Toronto's history. They brought with them the cultural values of conservatism, tolerance, and preference for order over radical change. These would have far-reaching effects on Canada's early development, and continue to shape Canadian identity to the present.

3. Here, let there be a city!

Toronto Public Library X 64-18

1904

This picture shows the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1904 which was the second worst fire in the city's history. The worst fire was a century before, during the War of 1812, when the city was pillaged by American troops under the command of Zebulon Pike during the Battle of York.

Fears of an American invasion (well-founded, as it turned out) shaped the government's planning of the early colony. The future city of Toronto was thought to have a good strategic location on the coast of Lake Ontario that could be easily defended from American attack, and it was made Upper Canada's capital. In order to open up the area to settlement most of the land around modern Toronto was bought from the Mississauga people in 1787, with a town being founded in 1793. It was called York and even though it was being built from the ground up, it was made the capital of the colony.1 When the American army showed up 20 years later, the town was still in its infancy, and the fire did little to impede its growth.

* * *

Toronto, on the other hand, was a safe distance from the border, had a protected and defensible harbour, and the Toronto Passage to Lake Simcoe was the fastest way to rush soldiers to the Great Lakes in the west. As an added bonus, Toronto was roughly halfway between the two settlement areas, making administration more convenient.

Before Dorchester could establish the capital he had to deal with the people who already lived around Toronto: the Mississaugas of New Credit who had moved into the region after the Wendat moved north. Dorchester organized the Toronto Purchase, where about 250,000 acres--most of modern Toronto--was 'bought' from the Mississaugas. The Mississaugas were paid a modest assortment of gun flints, kettles, mirrors, hats, and rum.

In what was part of a pattern of chronic abuse of First Peoples trust in the settling of Canada, the Mississaugas were cheated out of their ancestral lands. They believed that they were only agreeing to share the land, not surrender it, and that they would continue to receive payments for its use in perpetuity. According to historian Matthew Wilkinson, "The Brits were aware that the Mississaugas did not understand."1 Dorchester did not care. As far as he was concerned, all of the land around Toronto now belonged to the Crown.

The Mississaugas would not receive redress until 2010, when the Government of Canada finally agreed to pay a $145 million settlement to the band and its 1,700 members.

Lord Dorchester's successor was the energetic John Simcoe, a man who would leave his stamp on the early colony. On a surveying trip in 1793, Simcoe decided he'd found the right spot for the capital near the mouth of the Don River. He turned to his party and grandiosely declared, "Here let there be a city!"2

His soldiers set to work establishing York. They cleared the thick forests, laid out a ten-block street grid between Front and Adelaide Streets, and erected a new parliament building (a little to the east of this spot). They also started hacking a military highway from the shores of Lake Ontario all the way to Lake Simcoe, which would allow the British to rush troops to Lake Huron in an emergency. Simcoe decided to call this highway Yonge Street, after the British War Minister at the time. The original starting point of it is at the intersection just in front of you.

Simcoe did not like the indigenous names, and thought Toronto ought to have a British name. He settled on York (New York was already taken). Even at the time this policy was heavily criticized. One topographer, Isaac Weld, wrote in 1796:

"It is to be lamented that the Indian names, so grand and sonorous, should ever have been changed for others. Newark, Kingston, York are poor substitutes for the original names of the respective places Niagara, Cataraqui, Toronto."3

Simcoe next turned to the task of social engineering, hoping to create what he believed was the ideal society.

4. Engineering an Oligarchy

Toronto Public Library E 9-106 Small

1880

A cart passes the old Bank of Montreal building on the right, and behind it the elegant Beaux Arts-style customs house, signs of the city's prosperity in the second half of the 19th Century.

During the 1790s, Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe reasoned that the best way to prevent an American-style revolution in Canada was to model Canadian society on English society in the 1700s. This meant a rigidly class-based and explicitly unequal system, ruled by an unaccountable oligarchy of the rich and well-connected. To modern Canadians, a system like this sounds exactly opposed to Canadian values. Why did Simcoe think this was a good idea?

* * *

John Simcoe was himself a blue-blooded aristocrat and very much shared these views. He concluded that the only way to prevent a Canadian Revolution was to build from scratch a Canadian ruling class, exactly like the English one.

Simcoe's dreams went further: He was under the impression that American democracy was little better than mob rule, and would shortly descend into chaos and anarchy. He fervently (and apparently genuinely) believed that by developing Upper Canada into an orderly society with a strong aristocracy, he would demonstrate the inferiority of republicanism. The Americans in the Western states would be so impressed they'd throw off their government and beg the British Empire to take them back.

The loss of America evidently hurt Simcoe deeply, and he sounded like a jilted lover when he wrote to a friend "I would die by more than Indian torture to restore my King and his Family to their just Inheritance [the United States]."1 Simcoe's successor, Peter Russell, confided to a friend that "I must confess his Imagination seems to run away with him."2

So, the Loyalists were to be part of a social experiment: a new conservative society in British North America that was to be both the bulwark against and counterpoint to America's republicanism. As it would turn out Simcoe's vision for Upper Canada was largely realized. It goes without saying that his dream for America was not.

5. A Flawed Democracy

Toronto Public Library 982-26-17

1903

Horse-drawn carts dominate Wellington Street in this view from the early 1900s. One of the commercial buildings at the right is home to the Fancy Goods Company of Canada. Before this was the financial district, this neighbourhood was Toronto's main commercial district. Sadly, most of these buildings have been torn down and replaced with the skyscrapers before you.

Simcoe set up the colonial government to be a 'democracy' with every provision made, he wrote, "to lessen the undue weight of democratic influence." This is a euphemistic way of saying the democracy was a sham, and the aristocracy was to hold the real power.1

* * *

Where would this aristocracy come from? Upper Canada did not have one, so Simcoe decided to create one using Loyalist soldiers. He parcelled out land to them: 50 acres of free land for soldiers and 5,000 for officers (men of noble birth).2. The 100:1 ratio was thought sufficient for keeping the officers a safe social distance from their men.

Any other well-born or well-connected Loyalists were also deemed suitable candidates for the new aristocracy and given huge grants of land. Members of the first Executive Council were given 6,000 acres just for moving from Kingston to the new capital of York.2 15,000 acres went to America's old friend Benedict Arnold and his family.3

A 21st century reader would think this system the modern definition of corruption and they would be right. But within the ideology of 18th century European society it made perfect sense--in their eyes it was the only desirable way to run a society.

Simcoe's vision of society was largely realized by 1815, when a small clique of wealthy landowners, known as the Family Compact, had come to control all the levers of government in Upper Canada. Unfortunately, Simcoe's aristocratic ideology was bound to fail in Upper Canada, and his social engineering laid the seeds of future strife.

6. The Canadian Way

Toronto Public Library B 5-86d

1910

The Imperial Bank of Canada once stood on this spot. In this photograph it is covered with black bunting and flags to mourn the passing of King Edward VII. The dedication to the monarchy, and all things British, remained very strong in Toronto more than a century after Simcoe.

Along with the outward displays of loyalty to Britain, the thoroughly British values of 'peace, order, and good government' held wide appeal with Upper Canada's Loyalists. But Simcoe's plan to clone English society into Canada frustrated many Loyalists: They had already lived in North America and knew it was a very different place from the UK. Survival on this frontier required ingenuity, resourcefulness, and adaptability. The Loyalists were not about to unlearn all those hard-won lessons at Simcoe's urging. Instead this fusion of British and American values spawned an entirely new culture: the first inklings of a unique Anglo-Canadian identity.

* * *

Simcoe's obsession with doing everything the English way irked many Loyalists. Richard Cartwright, a Kingston businessman and Loyalist, wrote:

"He thinks every existing regulation in England would be proper here… He seems bent on copying all about the subordinate establishments without considering the great disparity of the two countries in every respect. And it would really not surprise me to see attempts made to establish among us Ecclesiastical Courts, tithes and religious tests, though nine tenths of our people are of persuasions different from the Church of England… [and] have been brought up in a country where there was the most perfect freedom in religious matters… this would certainly occasion almost a general emigration."2

Poor health prompted Simcoe to return to Britain in 1796 and shortly after retired. In five short years he had laid the foundations of Upper Canadian society and is today seen as one of Canada's founding fathers. His energetic promotion of British culture also helped Anglo-Canadian identity develop into something distinct from its neighbours in the south.

One British immigrant, writing decades later, exemplifies the fusion of the American and British experiences, which created a new culture altogether:

"My candid opinion is that if the Middle Class want to emigrate there is no better place in [North] America than Ontario and no better city than Toronto… new arrivals have to undergo what I call a grinding up, an assimilation. They have 1st a lot to unlearn, and then a lot to learn, you see I speak from experience--of course an Englishman thinks that we know nothing here, that as a mechanic or whatnot he is far ahead of us Canadians, and he might be if the conditions were the same, and after some time he finds that to suit the changed circumstances he has to adopt our plans. Many a one comes here with means and he does not find this out till his money is gone, then if he is made of the right stuff when he touches bottom, he puts his shoulder to the wheel and begins to rise… But poor industrious people are pretty certain to benefit themselves by coming here. They are at the bottom when they get here."3

7. Muddy Little York'

Toronto Public Library B 1-26b

1838

This fascinating sketch shows the fish market that was once located at the foot of Jarvis Street, when the shoreline extended all the way up to Front Street. Notice the triangular building on the right, which was called the Coffin Block. A newer building of the same shape occupies the spot today. Some of the women with baskets appear dressed in traditional First Nations clothing and have come to the market, probably by canoe, to sell their catch. What was life like in York at that time? A hint is supplied by the loveless nickname that became attached to the town in the early 1800s: 'Muddy Little York'.

* * *

"The Governor and Mrs. Simcoe received me very graciously. But you have no conception of the Misery in which they live… in one room they lie and set company… and in the other are the Nurse and Children squalling.. An open Bower covers us at dinner… and a tent with a small Table and three Chairs serves us for Council Room."

These homes were replaced by timber-framed buildings at the earliest possible opportunity. Brick homes, which cost about 10x as much to build, were marks of social standing for the colony's growing elite, and they began to appear soon after.1

Bad roads were a fact of life and "Rare indeed are kindly remarks about the early roads of Ontario," notes one historian.2 York's were particularly bad, especially as there were no storm drains or sewers, so when it rained, human excrement and trash was churned into the mud, turning the town into an impassable, reeking morass. Many took to calling the town 'muddy York,' or 'dirty Little York.'

These bad roads shaped Ontario's early development, and ironically cemented 'muddy York's' future dominance of the province. Land cleared for roads across Ontario often turned into a swamp that was nightmarishly difficult to navigate. Corduroy roads (logs laid side by side) were one solution, though they promised a teeth-chattering, bumpy ride. This meant the pioneers relied heavily on water transport to visit and trade with each other and with the outside world. Thus, few towns developed inland, and instead communities were almost all concentrated along the shores of Lake Ontario.

Simcoe had in fact wanted to make London the capital as well, but was dissuaded when he learned the difficulty of building a road to it. York's excellent harbour meant that it quickly became a transport hub, and Upper Canada's commercial capital as well as the political one. It started to grow quickly: 5,500 people lived in Toronto by 1832, more than double the size of the next largest city, Hamilton.3

Unsurprisingly perhaps, the inhabitants grew weary of having their town referred to as 'muddy Little York,' and with being confused with the original York, as well as the up-and-coming New York. In 1834 Council voted to incorporate as a city and revert to the old name Toronto. The Speaker proudly exclaimed "this city will be the only City of Toronto in the world!"4 This is no longer the case and there are now cities of Toronto in Kansas and Ohio. However, our Toronto is still the biggest.

8. Toronto Matures

Toronto Public Library B 11-33a

1885

This interesting picture shows two businesses you wouldn't typically see side-by-side: On the left, the W. Mahaffy & Son Horse Showing & Carriage Works, and on the right, the law offices of Sir John Beverley Robinson. One can imagine the stench of horse manure and the clanging of the blacksmith's iron invading Beverley's office as he met with clients.

These buildings are reminders of a time when Toronto was in an intermediate stage between frontier outpost and metropolis. This neighbourhood is part of the small ten-block site first laid out in the 1790s. But this area, and Corktown just to the east, were marshy and less desirable, the city's development shifted to the west, around Bay and Yonge Streets. This area east of the St. Lawrence Market stagnated until the first waves of poor immigrants arrived in the 1820s and 1830s, as most settled in this neighbourhood.

* * *

In Toronto a relatively peaceful, optimistic, and upwardly mobile society had come into being. A description of the people written in 1832 by William Proudfoot, a Presbyterian minister, does not sound so different from one a visitor to Toronto might write today:

"The people are very hospitable and in general very polite.--Canadians speak very well but late settlers from every country speak just as they did at home, and when you go into a Scotch settlement you see the same dress and hear the same dialect as you would do were you to visit the place where they come from. In some places nothing but Gaelic is spoken or understood--in others nothing but Dutch… French--and there are many who [use words like] 'guess' and 'calculate' and 'expect' from Yankeeland. In this country a person may place himself amongst a people where he will feel just himself as if he were at home…

"The people here are not poor. At present the majority of them who came into the country with scarce a dollar in their pockets are struggling with difficulties connected with settling a new country. Every year they are becoming more comfortable--even rich."2

Yet the seeds of strife had been planted by Simcoe's social engineering in the 1790s, and in 1837 issues were to come to a head.

9. Inequality Breeds Strife

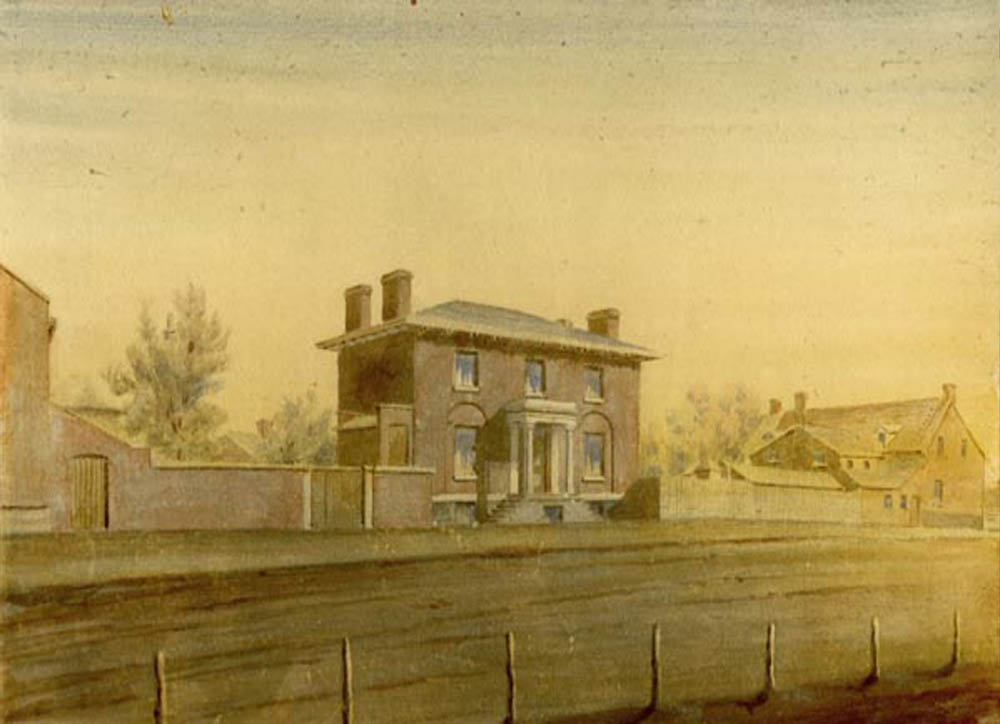

Toronto Public Library JRR 823 Cab

1830s

This building was the Canada Company's office in the 1820s and 1830s. The Canada Company was founded by the British government to manage and sell the crown and clergy reserves land of Upper Canada. In fact, the Canada Company was largely a tool of Upper Canada's small and tightly-knit aristocratic ruling class and ensured they got all the best land, even if they never intended to farm it. As new settlers arrived in the colony they found themselves exploited by this unfair system. They took their concerns to the Legislative Assembly and were outraged when they discovered that the 'democracy' Simcoe set up was not a real democracy at all, and their demands were contemptuously ignored.

* * *

This system of land ownership was modelled on the British one, which was bound to fail in the Ontario context. The British countryside was densely populated and covered in farms that produced the wealth to support the gentleman aristocrats. Upper Canada on the other hand was sparsely populated, forested, and undeveloped.

As new settlers from Great Britain poured into the colony in the 1820s and 1830s they demanded land, driving up prices, which in turn allowed the Family Compact to enrich themselves by selling off tiny parcels. Because these elites ran the government and appointed the bureaucracy--the magistrates, surveyors, tax collectors, and militia officers--they had many tools at their disposal to ruthlessly extract profit from the land-hungry immigrants. Many simply sat on their land, waiting for it to go up in value, a problem not unfamiliar to Torontonians today. "In the end," writes one historian, "Upper Canada became a paradise for the land speculators."1

As the new settlers worked strenuously to turn their tiny plots into farms, they enviously regarded the excellent undeveloped land owned by the Family Compact. One settler writing at the time complained "Much land is held by absentee proprietors, or the members of the party who sway the councils of the province."2

The new settlers sought to address this unfair distribution of land, along with a host of other issues, through the elected Legislative Assembly. The Family Compact responded by simply ignoring the assembly, and governing the province in an increasingly autocratic manner.

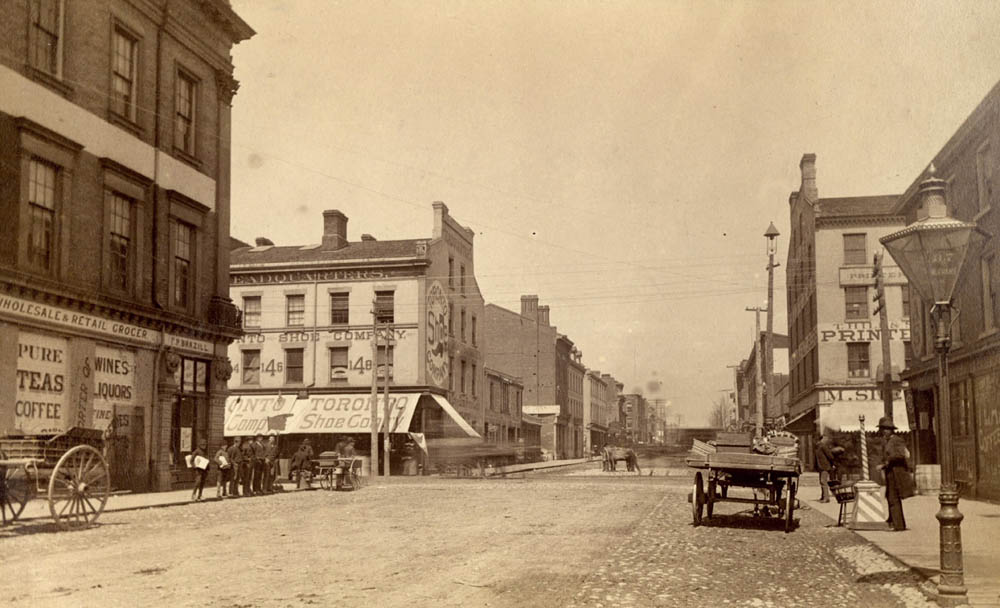

10. The Rebellion of 1837

Toronto Public Library B 11-3b

1890

This is a view of Jarvis Street in 1890. The street is named after one of the most prominent families in the Family Compact, who were particularly hated by the reformers of the 1830s for their corruption and wealth. The Reformers were led by the newspaper editor William Lyon Mackenzie, and his ferocious editorials helped incite people against the elites in the Rebellion of 1837. The brief and at times comical rebellion ended in failure, but its effects would ripple outwards, eventually leading to the true responsible democracy the rebels had fought for.

* * *

The Family Compact fought every attempt to curtail their power. In 1826, some members of the Family Compact dressed as First Nations people, broke into the Colonial Advocate's offices, and smashed the printing press. One of the culprits was Samuel Jarvis. In an attempt to appease Mackenzie, Francis Bond Head was appointed as the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada in 1835, a move which would backfire spectacularly. In 1837 tensions came to a head.

Mackenzie saw the outbreak of the rebellion led by Louis-Joseph Papineau in Lower Canada (Quebec), and seized his chance. He declared his own revolt against Upper Canada's government, demanding "Independence!" and drafting a new constitution.

Bond Head shrewdly framed the rebellion as an American insurgency. He pointed to MacKenzie's support for American-style reforms and an earlier visit to the country as evidence of a nefarious plot to turn Upper Canada into an American state. He grandly challenged the Americans, "Let them come if they dare."2 By making the rebellion an issue of British vs. American rather than aristocracy vs. everyone else, Bond Head was effective in limiting Mackenzie's popular support and maintaining the loyalty of the militia units, which largely comprised Loyalists and their descendants who wanted nothing to do with the United States.

Mackenzie was nevertheless able to assemble 400 rebels and march on Toronto. On the northern approach to the city they halted and set up a base at Montgomery's Tavern in modern Eglinton. It was there that Bond Head led 1,000 trained and equipped militia against the ragtag rebels. In a brief engagement that left four dead, the rebels broke and fled. With his insurrection defeated, Mackenzie fled to the United States.

While the rebellion may have failed, it caused the British government to sit up and take notice. They tasked Lord Durham with determining the sources of discontent and proposing remedies. Durham immediately grasped the unsustainability of the Family Compact's rule, calling them "a petty corrupt insolent Tory clique." It was impossible, he wrote, "to understand how any English statesman could have ever imagined that representative and irresponsible government could be successfully combined."3

Durham's recommendations included a government responsible to the legislature, along with a variety of reforms that would squeeze the Family Compact out of power. While many of these reforms would take years to be enacted, they marked the beginning of the end of the Compact's dominance, the decline of the Loyalist aristocracy and the beginning of truly democratic government in Canada.

The decline of the Family Compact coincided with a wider revolution that would reshape Toronto and bring it into the modern world: the Industrial Revolution.

11. The Irish Arrive

Toronto Public Library B 12-23a

1872

A ceremonial arch covered with branches has been erected over King Street during a visit by the Governor General, the Marquess of Dufferin. Arches like this were a common sight in 19th Century Toronto, and were put up whenever a British dignitary as a way for Torontonians to display their loyalty to the Empire.

The Irish were he largest contingent of immigrants to Toronto in the mid-19th Century, after English and Scottish, and they had a rather complicated relationship with the British Empire. The first to arrive in the 1820s were mostly Irish Protestants who were fiercely loyal to Britain, though they were somewhat looked down upon by the city's English and Scottish inhabitants. In the 1840s however, hungry and diseased Irish Catholics fleeing the potato famine began arriving at the city in the thousands, much to the consternation of Toronto polite society.

* * *

"The want of good servants is a more serious evil [than the lack of vegetables]. I could amuse you with an account of the petty miseries we have been enduring from that cause, the strange characters who offer themselves and the wages required. Almost all the servants are of the lower class of Irish emigrants, in general honest, warm-hearted and willing; but never having seen anything but want, dirt, and reckless misery at home, they are not the most eligible persons to trust with the cleanliness and comfort of one's household."1

Yet it was the arrival of a wave of Catholic Irish immigrants in the midst of the Irish Potato Famine in 1847 that would strain Toronto's self identity as an open and tolerant city.

Before the famine, most Irish Catholics had chosen to emigrate to the United States. The desperation sparked by this catastrophe meant that for the first time tens of thousands set sail for Canada on ships "so ghastly as to beggar description."2 So many died on the six week voyage that they came to be known as 'coffin ships.'

Coffin ships sailed into Lake Ontario and disembarked 38,000 Irish at Toronto in 1847 alone, more than the city's entire population (though most would continue onwards to other destinations). The horrid conditions of the immigrants shocked Torontonians. Fever sheds were set up on the waterfront just a couple blocks from this spot to quarantine the sick--1,100 died in them.2 Churches and charities trying to help these immigrants were overwhelmed.

12. Catholics and Protestants

1880

This image shows a line of cabs waiting outside St. James Anglican Cathedral, the oldest parish in the city. The current building was completed in 1853, and was attended by many Irish Protestants. There were severe tensions between the Irish Protestants and Catholics that often broke out into open violence. One chronicler describes remarkable scenes in the 1870s when a Catholic procession was intercepted by a mob of Protestants on Church Street, where you are now standing.

"About half-past three the procession left [St. Michael's] Cathedral, and, headed by a squad of police, moved along Shuter Street amid the yells and hootings of the large mob. Just as the foremost ranks reached the corner of Church and Queen Streets [three blocks north of here] a perfect volley of stones came upon them from Queen Street. A halt was made, the police charging upon the rioters, who were soon driven off… The procession moved down Church street... the riot assumed the most serious aspect; revolvers were freely used, the fight between the police and the crowd being kept up for a considerable time."1

* * *

Toronto's Irish Protestants didn't react well to the new arrivals due to their ancestral hatred for the Catholics. Ireland was Britain's first colony, and for 300 years the indigenous Catholic Irish had been brutalized, dispossessed, and subjected to violence that sometimes bordered on genocide. The Protestants came from England and moved onto land stolen from the Catholics. Many treated the Catholic Irish as members of a subhuman inferior race.

Thus, when the Catholics arrived, those bitter centuries-old hatreds were transplanted to Canada. Many of Toronto's Irish Protestants joined the Orange Order, a sort of paramilitary fraternal organization, and in response, the Irish Catholics formed the Hibernian Benevolent Society. As we've seen, street fights and even riots between the two groups were common.

The rest of Toronto's population were predominantly English and Scottish, and initially their general attitude was of goodwill and pity towards the Irish arriving during the Potato Famine. However, the scale of the human tragedy caused hearts to harden. Those Irish Catholics that stayed in Toronto were destitute, and they mostly moved into East End neighbourhoods like Cabbagetown and Corktown. These impoverished slums trapped many of these new immigrants in a cycle of poverty and contributed to increasingly widely held racist stereotypes of the Irish as poor and lazy.

These stereotypes were fueled by George Brown, editor of the Globe. "Irish beggars are to be met everywhere, and they are so ignorant and vicious as they are poor" he wrote in one article. "They are lazy improvident and unthankful, they fill our poor houses and our prisons."2 Newspapers like the Globe also fanned suspicions about the loyalty of these immigrants, wondering if they preferred the Catholic Church and the Fenian Brotherhood (an American Irish organization agitating for Irish independence) to the British Empire.

Despite the negative stereotypes, the Irish Catholics quickly integrated into Toronto society and many rose into the middle class, working as butchers, carpenters, tailors, and shopkeepers. "Far from being a ghettoized minority, the vast majority of Irish Catholics had secured a position in the social and economic mainstream of Ontarian society."3

13. Black Canadians

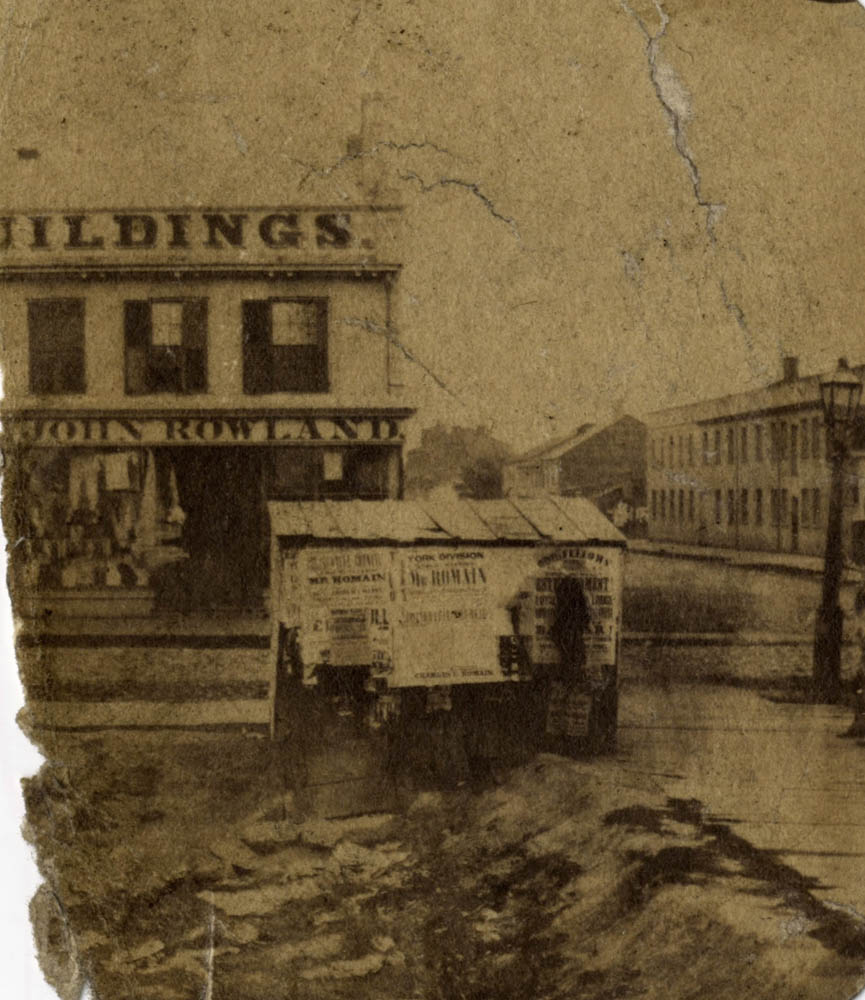

Toronto Public Library B 8-60b

1860s

This grainy early photograph shows a newspaper kiosk on the corner of Queen and Yonge Streets. This was once the neighbourhood of MaCauley Town, an area of tenement slums where many of Toronto's new immigrants crammed together in the mid-1800s. It is also where much of Toronto's black settlers made their homes. Most of MaCauley Town was bulldozed in the early 20th Century and replaced with shopping centres and the city hall complex.

Toronto's black community was present from the very founding of the city and played a key role in the city's development. What brought them to Upper Canada?

* * *

Not all Africans in Canada were free however: the Act to Limit Slavery didn't apply to the tiny number of slaves already brought to Canada, and they remained in bondage. One of Upper Canada's Lieutenant-Governors, Peter Russell, owned slaves.2 It was not until 1833 that the last two slaves in Upper Canada were freed.

In those years, the threat of American annexation and the reintroduction of slavery was terrifyingly real, and certainly never far from the thoughts of Upper Canada's black community. They quickly came to see the British government as the guarantor of their freedom, and could be counted upon as some of Canada's fiercest and most loyal defenders.

One of the most notable of these was Richard Pierpoint, who earned his freedom fighting alongside the British during the Revolutionary War. Afterwards he settled as a farmer in Upper Canada, until the War of 1812, when he petitioned the government to establish an all black militia unit to defend Canada. Pierpoint, now 68, served in its ranks as a corporal alongside black volunteers from across Upper Canada. By all accounts the unit distinguished itself at many engagements, including the decisive Battle of Queenston Heights. Pierpoint and many other black Canadians played an important role in defending Canada's independence when it was at its most precarious. Pierpont was the subject of a Heritage Minute, a 60 second short video, by Historica Canada in 2015.

By the mid-1800s, many of the northern American states had outlawed slavery. Abolitionists sympathetic to the slaves' plight organized a sophisticated network to smuggle slaves out of the South and to the free states or Canada. It later became known as the Underground Railroad.

14. The Underground Railroad

Toronto Public Library B 4-82b

1906

Here we see another view of MaCauley Town, the tenement slums where many immigrants settled, including many slaves who had escaped to Canada along the Underground Railroad. Their harrowing tales of slavery infuriated Canadians and there was great sympathy for their plight. Many of those who settled around here established lives for themselves unthinkable in the United States of the mid-1800s. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, who settled in Toronto in 1835, became a real estate magnate with holdings across Toronto, while his son Anderson R. Abbott became the first Canadian born black doctor. They could not give up on their kinsmen still in bondage, and when the US Civil War began both father and son left Canada to enlist with the Union Army.

* * *

By 1852, the society reported that 30,000 refugees had resettled in Ontario--many in Toronto--a number which rose dramatically in the years after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in America, which meant slaves in free states could legally be kidnapped and returned to their owners, meaning the northern states were no longer safe.2 Many slaveowners, furious that their 'property' had escaped to Canada, took their claims to Canadian courts, but they were rejected every time.

Some escaped slaves who settled in Canada wrote back to their kinsmen to urge them to come to Canada. "How much longer, in the name of God, shall my people remain in their state of degradation under the American republic?" wrote Henry Gowans, who had escaped from Virginia.

He continued:

"The man who was 'a bad n-----' in the South, is here a respected, independent farmer.... The 'n-----' who was so 'BAD' among Southerners, as to be scarred with whips, put in the stocks, chained at his work, with ankles sore from the irons, ... put in jail after jail, hunted by hounds, - stands up here at the North [Canada], a man respectable and respected. I don't ask any one to take my word for it, merely. Ask the people of Peel, Wellesley, Woolwich, and Waterloo - those are the places where I am known."3

Gowens was painting an idyllic picture of Canada that did not always match reality. Black Canadians still struggled with many of the same issues of casual racism and discrimination that they would have faced in America: demeaning shows were performed in blackface, some whites demanded school segregation and feared competition for jobs, and black Canadians faced discrimination at the hands of the police and in finding work.

In response many black Canadians settled in tightly-knit communities, like MaCauley Town where you are standing. Historian James Walker writes that these neighbourhoods fostered "a strong sense of group identity and mutual reliance, combined with the unique identity provided by churches." This unique Canadian experience "produced an intimate community life and a refuge against white discrimination."4

15. Industrial Transformation

Toronto Public Library -341687

1901

This photo shows an extravagant arch erected along the parade route of King George V during his visit to Toronto. A cameraman in the left of the photo has a hood over his head as he prepares to take a photograph. The tall building in the back is the old City Hall. The King's visit came at the end of a 50 year period of seismic changes in Toronto, that catapulted 'Muddy Little York' into the modern age. These changes were driven by the Industrial Revolution.

* * *

In the mid-1800s all of this rapidly changed. The steam engine meant people could now harness the immense energy contained in coal, and suddenly people had access to vastly more power than previously conceivable. Steamships and trains caused the speed of movement to skyrocket while the cost of transportation plummeted. Improved agricultural techniques made food cheaper and the population exploded. All of these new people needed jobs, and they found them working for wages in factories concentrated in downtown Toronto, where steam-powered machines churned out clothes, equipment, and goods of every kind at an astonishing rate.

These must have been exciting years, when those essential aspects of modern urban life that we now take for granted, were first established. A public water system for drinking and firefighting was built in 1857. The telephone network first set up in the 1870s. Electric street lights were installed in the 1880s. The streetcar system was established in 1892 (oddly, only after St. Catharines and Ottawa had built them).

Despite being beaten to the electric streetcar, Toronto grew most rapidly and soon came to dominate the province. The reasons for this are relatively simple. As one historian explains:

"It had a good harbour, [and] railways from east, west, and north converged on it. For the rest one can resort to a cliche that success breeds success, or to the metaphors of snowballs and magnets. Finance, industry, marketing, and business of all kinds, once having a base, attracted each other. There were still industries scattered all over Ontario, but the continued growth of many towns was reduced by the drain to Toronto. Hamilton alone remained in the competition."1

In 1832 only about 10,000 lived in Toronto, or about 4% of Ontario's population. By 1901 the population had soared to 238,000, 12% of the provincial total. But the city still had a ways to go before it could claim to be Canada's Metropolis. That title still belonged to the much older, and better established city of Montreal.

Home to many venerable financial, commercial, and media institutions, and a 1901 population of 325,000, many Montrealers looked upon the upstart Toronto with disdain. As Glazebrook writes, many Montrealers felt Toronto was "sprawling, crude, an over-grown village, lacking in any sophistication or metropolitan atmosphere." Nevertheless "this western outpost was feeling its way toward the stature of a real city, to be the focal point of urbanism in the province."2

Endnotes

1. Before the City

1. Carl Benn, "First Peoples, 9000 BCE to 1600 CE," The History of Toronto: An 11,000 Year Journey. City of Toronto. Online.

2. Alan Rayburn. "The real story of how Toronto got its name." Natural Resources Canada (2013). Online.

2. The Loyalists

1. G. P. De T. Glazebrook. Life in Ontario: A Social History. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968). 18.

2. "Loyalists during the American Revolution," University of Groningen. 2012. Online.

3. Glazebrook, 19.

4. John Ferling, "Myths of the American Revolution," Smithsonian Magazine. Jan. 2010. Online.

5. University of Groningen. Online.

6. Bruce G. Wilson. "Loyalists," The Canadian Encyclopedia. Apr. 2009. Online.

3. Here, let there be a city!

1.Peter Kuitenbrouwer, "Reconciling the Toronto Purchase", National Post. June 8, 2010. Online.

2. Allan Levine, Toronto: BIography of a City. (Madeira Park: Douglas & MacIntyre, 2014), 20.

3. Edwin Guillet, Pioneer Settlements in Upper Canada. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969), 55.

4. Engineering an Oligarchy

1. Lillian Gates, Land Policies of Upper Canada. (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1968), 26.

2. Gates, 29.

5. A Flawed Democracy

1. Gates, 32.

2. Glazebrook, 162.

6. The Canadian Way

1. Levine, 30.

2. Conway Cartwright, Life and Letters of the Late Hon. Richard Cartwright, (Toronto: Belford Brothers, 1876), 57.

3. Glazebrook, 136.

7. Muddy Little York'

1. Levin, 24.

2. Glazebrook, 30.

3. Levin, 24.

4. Edith Firth. The Town of York: 1815—1834; A Further Collection of Documents of Early Toronto. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966), 297.

8. Toronto Matures

1. Glazebrook, 59.

2. Glazebrook, 39.

9. Inequality Breeds Strife

1. John Clarke. Land, Power, and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press, 2001), 162.

2. Clarke (2001), 163.

10. The Rebellion of 1837

1. Adam Bunch, "The infamous, bloody 1817 duel at the corner of Yonge and College." Spacing Magazine, Feb. 5, 2013. Online.

2. Levin, 48.

3. Robert C. Lee, The Canada Company and the Huron Tract, 1826–1853. (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2004), 149.

11. The Irish Arrive

1. Glazebrook, 67.

2. Glazebrook, 67.

3. Brian Clarke, Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Canadian Community in Toronto, 1850-1895. (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993), 16.

12. Catholics and Protestants

1. J. Timperlake, Illustrated Toronto: Past and Present, (Toronto: P.A. Gross, 1877), 153.

2. Levin, 77.

3. Clarke (1993), 15.

13. Black Canadians

1. Levin, 11.

2. Levin, 12.

14. The Underground Railroad

1. Levin, 116.

2. Levin, 116.

3. George Elliott Clarke, "'This is no hearsay': Reading the Canadian Slave Narratives," Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada, (2002), 27.

4. James Walker, "Black Canadians", The Canadian Encyclopedia, Feb. 19, 2013. Online.

15. Industrial Transformation

1. Glazebrook, 178.

2. Glazebrook, 185.

Bibliography

Benn, Carl. "First Peoples, 9000 BCE to 1600 CE," The History of Toronto: An 11,000 Year Journey. City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/museums/virtual-exhibits/history-of-toronto/first-peoples-9000-bce-to-1600-ce/

Bunch, Adam. "The infamous, bloody 1817 duel at the corner of Yonge and College." Spacing Magazine. Feb. 5, 2013. http://spacing.ca/toronto/2013/02/05/the-infamous-bloody-1817-duel-at-the-corner-of-yonge-college/

Cartwright, Conway. Life and Letters of the Late Hon. Richard Cartwright. Toronto: Belford Brothers, 1876.

Clarke, Brian. Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Canadian Community in Toronto, 1850-1895. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1993.

Clarke, George Elliott. "'This is no hearsay': Reading the Canadian Slave Narratives," Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada. 2002.

Clarke, John. Land, Power, and Economics on the Frontier of Upper Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press, 2001.

Ferling, John. "Myths of the American Revolution," Smithsonian Magazine. Jan. 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/myths-of-the-american-revolution-10941835/

Firth, Edith. The Town of York: 1815—1834; A Further Collection of Documents of Early Toronto. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1966.

Gates, Lillian. Land Policies of Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1968.

Glazebrook, G. P. De T. Life in Ontario: A Social History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1968.

Guillet, Edwin. Pioneer Settlements in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969.

Kuitenbrouwer, Peter. "Reconciling the Toronto Purchase", National Post. June 8, 2010.

Lee, Robert C. The Canada Company and the Huron Tract, 1826–1853. Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2004.

Levine, Allan. Toronto: BIography of a City. Madeira Park: Douglas & MacIntyre, 2014.

Rayburn, Alan. "The real story of how Toronto got its name." Natural Resources Canada. 2013.

Timperlake, J. Illustrated Toronto: Past and Present. Toronto: P.A. Gross, 1877.

University of Groningen. "Loyalists during the American Revolution," 2012. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/outlines/history-1994/the-road-to-independence/loyalists-during-the-american-revolution.php

Walker, James. "Black Canadians". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Feb. 19, 2013. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/black-canadians

Wilson, Bruce G. "Loyalists," The Canadian Encyclopedia. Apr. 2009.