Walking Tour

Fear, Hate, and Xenophobia

Toronto's Stanley Barracks

Andrew Farris

Stanley Barracks was once a sprawling military base that covered much of the grounds around this spot.. Today only one building from the barracks survives: the officers' quarters. The base was used throughout the 19th and into the 20th Centuries, but one of its darker and lesser known chapters was its use as a receiving station for interned 'enemy aliens' between 1914 and 1916.

The men imprisoned here had immigrated to Canada from countries that Canada went to war with during the First World War. Most were interned because they were destitute, and Canada had criminalized destitution amongst 'enemy aliens'--a new legal category created for people born in enemy countries.

Across Canada some 8,579 people were interned during the First World War. Stanley Barracks was one of a nationwide network of receiving stations where newly arrested internees were processed, before sending them on to other more permanent camps—often in the remote wilderness.

The enemy alien experience in the First World War is a frightening cautionary tale that shows us how our society can turn on whole categories of people so abruptly, and then look away as they are abused and their rights trampled upon.

On this short tour of what remains of the Stanley Barracks, we will see where the prisoners were once kept, learn their individual stories, and consider the poisonous legacy of events that were all but forgotten until relatively recently.

This project is the result of partnerships with the Little Italy College Street BIA, the Toronto Chinatown BIA, and the Toronto Railway Museum.

1. Toronto in 1914

October 1914

This photo, which was taken from across the street from where you now stand, shows soldiers of the 48th Highlanders marching into the fort a few months after the start of the First World War. At the outbreak of war, all Canada was swept up in a patriotic fervour—few places more than Toronto.

Compared to its cosmopolitan image today, the Toronto of 1914 was one of the most British places in Canada—85% of the population claimed British ancestry, and fully r112,000 of the city's residents had immigrated from Britain since 1900.1 It was also seen by the rest of Canada as a bastion of the prudish and god-fearing social mores that defined the Victorian-era, earning it the derisive nickname 'Toronto the Good'. "In many ways, Toronto was the patriotic hub of the country," says Wayne Reeves, chief curator at the City of Toronto.

As we will see, the outsized patriotism of Torontonians and their enthusiasm for both the British Empire and the world war it was embarking upon, would have terrifying ramifications for those residents of the city who came from countries that Canada was now at war with.

* * *

The crowds erupted in cheers. "War fervour was breaking out in spontaneous parades," writes the historian Pierre Berton. "In Toronto that night, a little band turned up, seemingly from nowhere as the throngs in front of the Star building cheered themselves hoarse, then roared out a string of patriotic airs. Within a block, as the band moved west along King Street, the crowd had swelled to three thousand."2

To our eyes, this excitement appears naive and baffling. That's only because we know what was about to happen. The war would change everything.

Millions would die, including 60,000 Canadian soldiers, and many millions more would be maimed and traumatized for the rest of their lives. The horrors seen on the battlefields of this war surpassed the wildest imaginings of people in 1914. By 1918 almost all the combatant nations were on the brink of collapse and revolution—including Canada. The 1917 Conscription Crisis remains the greatest threat to Canadian unity since Confederation.

The war would lead the Canadian government to set a grave precedent in its suppression of civil liberties. The sweeping and draconian War Measures Act, with its measures for targeting minority groups and suspending parliamentary democracy, would haunt this nation's politics for decades to come.

Not just for Canada, but for the world, the First World War was the defining event of the 20th century. We are still living through its aftershocks.

2. The Hysteria of 1914

October 1914

In this image we see a piper leading a company of the 48th Highlanders into the camp. This photo was taken at the height of the war hysteria in October 1914. As soon as war was declared Canadians started seeing spies everywhere. Every fire, assault, or accident was blamed on enemy saboteurs. Just like in the rest of Canada, in Toronto suspicion immediately fell upon the tens of thousands who had been born in the opposed Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary—and starting that October, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria.

The War Measures Act of August 1914 officially redesignated those born in enemy nations as 'enemy aliens', creating a new legal category for them and stripping them of almost all their civil liberties and the right to due process. The government began setting up internment camps to hold those denounced as spies or traitors.

* * *

"Although I am a German, I, like the majority of my countrymen in Toronto, have no sympathy with Wilhelm for this war. We are not sorry, however, that it has broken out, for the simple reason that our hopes of a German republic being formed hinge on this war. Mark my words: if the Kaiser loses, Germany becomes a republic."1

He would ultimately be proven right, though he could scarcely have imagined that the short-lived Weimar Republic would be followed by the rise of the Nazis and another more terrible world war.

The Toronto Star ran a very reasonable sounding editorial on August 20, 1914 (two days before passage of the War Measures Act). It counselled people to show consideration for the Germans and Austrians living in Canada, saying they were:

"as genuinely concerned for the welfare of Canada as are our own people. Their interests are the common interests. They were of foreign birth, but they came to the new world to seek a new life. Here they have earned a livelihood, have acquired homes, built up businesses, and here their children were born."

They published a letter from an Austrian man who was encouraging all Canadians to participate in a mass letter writing campaign to Germany and Austria-Hungary, so people in those countries could understand that "the Canadian people had a right to express their indignation about this European war." While it doesn't seem very likely people in those countries cared at all what people in Canada thought, he nevertheless continued "If all people on the American continent who do not agree with this war would write only one letter each to a friend in Europe, stating their own convictions, the war would be fixed in a month."

It's a heartwarming if preposterous sentiment. One can't help but wonder if he was being sarcastic when he assured the Star's editors that in his letters, "I forgot not to point out the chivalrous and dignified attitude of the whole Toronto press towards us Austrians and Germans."2

With some exceptions like the above editorial, the Toronto press was decidedly not chivalrous and dignified to Toronto's Austrians and Germans. A brief survey of the headlines in Toronto newspapers from that period gives a sense of the atmosphere of the day:

"Many Spies are Employed as Waiters at the Big Hotels," wrote the Toronto Daily News.

"German Spies Were Active at Scarboro," declared the Ottawa Citizen.

"Toronto Spy Escapes."

"Alleged Spies had Notebook in German."

"Austrian Spies Arrested."

"Toronto Wireless Seized by Police: A German Was Discovered to be Operating a Private Plant in the City."3

The constant drumbeat of reports like this terrified people. People were constantly reminded to be vigilant of potentially disloyal immigrants, and report them to the police on the slightest suspicion.

Of course we know today there were virtually no enemy spies in Canada at this time. None of those six incidents we just mentioned actually had anything to do with spies. However, articles revealing the more mundane explanations for events did not make for very good headlines.

In hindsight this appears obvious, yet we shouldn't dismiss such hysteria as something only the ignorant people of 1914 could fall victim to. The entire episode sounds eerily similar to the Islamic terror hysteria in the dark days after 9/11, when western societies once again regarded a whole category of immigrants with suspicion and distrust. Terrorist plots by immigrants were regularly uncovered, only to later turn out to be fabricated or the result of a misunderstanding.

By 1916 the entire spy hysteria completely dissipated—Canadian newspapers more or less stopped mentioning spies completely. Similarly, the threat of Islamic terror, which so obsessed western societies in the 2000s, now seems almost a curious footnote in history. Yet it is one that the Muslim Canadians who lived through that time will never forget.

3. The Internment System

City of Toronto Archives Fonds 1266, Item 4985

1925

This photo shows dragoons trotting out of one of the gates of the Stanley Barracks past a guard presenting arms. The old gated building in the foreground of this picture has been replaced with a modern glass and steel one built in its footprint. In the background we can see the officers' quarters, the only part of Stanley Barracks that survives today.

As enemy alien paranoia surged across the country, the calls for calm and consideration towards them were drowned out by fear and hatred. Prime Minister Robert Borden apparently bought into these sensationalized reports enough to ask the commissioner of the Dominion Police if they had enough ammunition to protect Toronto from an armed uprising of enemy aliens—or worse, a full-scale military invasion by German and Irish immigrants from the United States.1

The hysteria quickly turned ugly. Only days after the war started, "an unruly and vicious mob cornered a number of immigrants on the streets of Toronto, forcing them to kneel and kiss the Union Jack."2

Many employers began firing the enemy aliens in their employ; this included everyone from factory workers and hotel waiters to university professors and city administrators. Many of those fired were working class men who were destitute and essentially unemployable. The government responded by beginning to send destitute enemy aliens to internment camps.

* * *

It appears that Toronto's registrar, Judge Emerson Coatsworth, was particularly harsh and arbitrary. Reinhold Buchs had applied to travel to the United States—as he was required to do under the new regulations. For this he was arrested and brought before Coatsworth, who sentenced him to internment. When the commandant at the camp at Stanley Barracks received Buchs he was puzzled and sought clarification: Buchs appeared to have been following all the regulations and had many people vouch for his good character and loyalty. Coatsworth responded that he had made contradictory statements about his past and also as a mechanic he could be of use to the German Army. So Buchs was to spend years behind barbed wire.3

Erwin Kohlman worked as an administrator for the City of Toronto and was fired from his job for his German origins. To add insult to injury, Coatsworth decided that Kohlman was a "busybody" and should be interned as well.4

Coatsworth also saw internment as a way to get poor working class men off the streets. Pronouncing the sentence of internment on two destitute men, he said: "A wretched lot, these enemy aliens enjoy the benefits of British institutions and traditions which they have done nothing in this war to earn. They are a stain on the national honour and should be removed."5

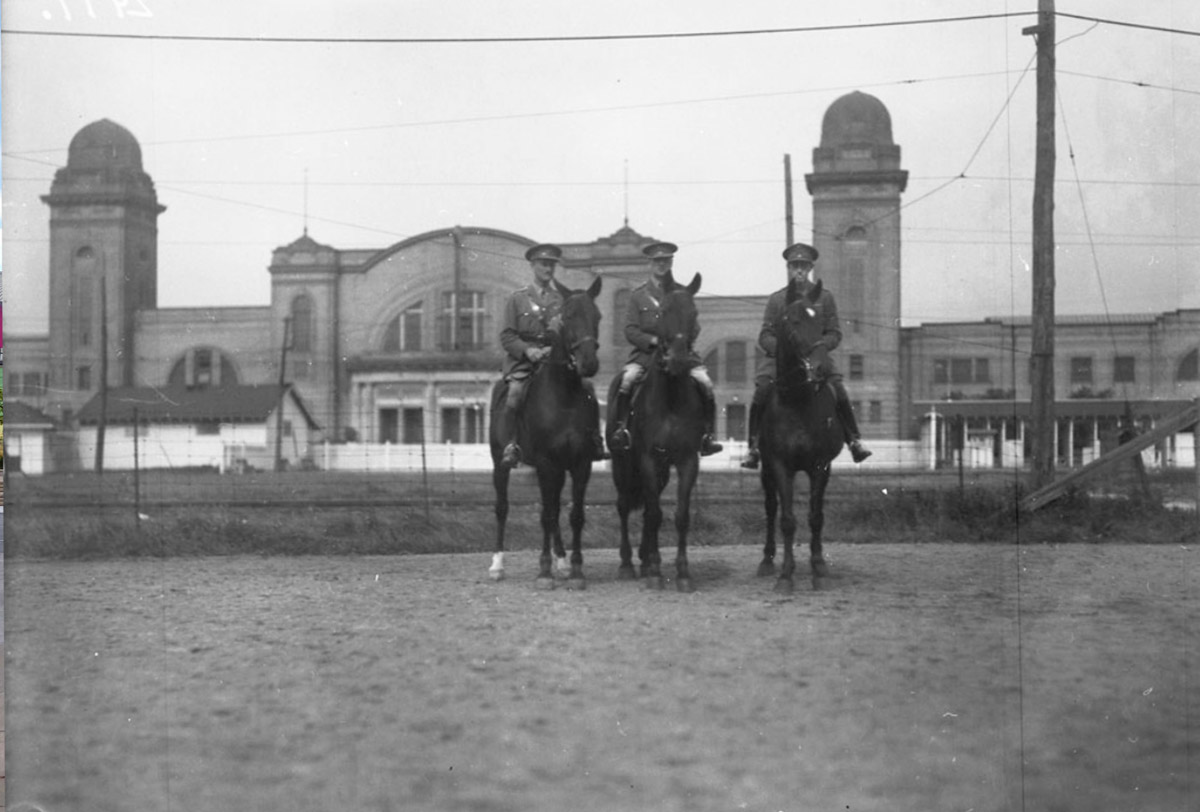

4. The Canadian National Exhibition

1926

Three officers on horseback pose for a photo in front of the Coliseum building at the Canadian National Exhibition. Today that building has been replaced by Exhibition Place.

Stanley Barracks was established here in 1840-1, replacing Fort York as the main military base in Toronto. The surrounding area was made a military reserve and preserved from development as Toronto grew around it. Stanley Barracks only occupied a small part of the reserve, so Toronto began using these grounds to hold the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) starting in 1879.

The exhibition has been held ever since at the end of August and over the Labour Day weekend. It's the largest fair in Canada and one of the most popular events on Toronto's social calendar. Around the early 1900s, grand permanent exhibition buildings, like the Coliseum you see in this photo, were erected all across these grounds.

During the First World War the military presence at Stanley Barracks grew gigantically, and the military took over the CNE grounds, turning many of its buildings into barracks and training grounds. By the end of 1914 some 4,500 soldiers were quartered at the CNE, rising to 10,000 a year later.1

* * *

"All branches of the Exhibition, as arranged this year, will harmonize and blend into one grand outburst of patriotic fervour… No doubt the model military camp will attract thousands of visitors, a great many of whom have relatives at the front."2

Visitors to the CNE would be entertained by soldiers carrying out military drills and fighting in realistic-seeming trench assaults. There were even mock air and sea battles: a biplane demonstrated bomb dropping, and a little patrol boat hunted a 'German U-boat' on the lake. There were exhibits of war trophies, blood-stained and bullet-holed uniforms brought from the front, and endless military parades accompanied by martial music.3

All of this was intended to arouse the emotions of Torontonians, and encourage young men to enlist.

Some military overtones of the CNE continue to this day, though rather than celebrate the glory of war, they honour the sacrifices of veterans. Starting in 1921, a "Warriors Day," parade of veterans was held on the second day of the Exhibition. In those early years, 30,000 participated. In 2019, the number of veterans taking part was just below 3,000.4

5. The Receiving Station

1920

This photo shows a gun team of the Royal Canadian Dragoons on the grounds of the Stanley Barracks. In the background you can see the orderly room, which once stood roughly where the gates to Stanley Barracks are today. The huge military base here made it an obvious choice for Toronto's internment station: There was high security, no shortage of guards, and it was easy to supply. Troops began preparing one of the barracks buildings to start accepting internees in September 1914.

The privates' barracks on the fort's west side was chosen for the internment station and set up to hold 90 internees. Preparations took some time as a barbed wire enclosure was erected around the block and an adjacent "Prisoner Yard," and metal bars placed on the block's windows. The first German reservist was sent there on September 7, though the camp would take some time yet to be ready.1

* * *

Based on its interpretation of the Hague Convention's rules governing the treatment of prisoners of war (POWs), Canada decided to sort internees into first and second-class categories. Those prisoners of 'officer-class' were put in the 'first-class' and not required to work, given better food and accommodation, and allowed more privileges. They would generally be transferred from Stanley Barracks to other military facilities like Kingston's Fort Henry.

Enlisted men were second-class, and were required to work (theoretically only in limited circumstances), and made to live in worse conditions. They would be sent to remote forced labour camps like Kapuskasing in northern Ontario or Spirit Lake in Quebec.

Though most of the internees were civilians, the government still defined them as prisoners of war and also sorted them into officer and enlisted class categories. They did this by determining their social rank: middle and upper class internees were considered first-class, while working class and poor internees were second-class.

In addition, Germany had lodged a number of diplomatic complaints about German civilian internees being forced to do hard labour, which was a violation of the Hague Convention. The Canadian government responded by classifying all German internees 'first-class'. Second class was reserved for interned Austro-Hungarians, Ottoman Turks, and Bulgarians, whose governments were less likely to complain (as in the case of Austria-Hungary), or did complain but Canada felt they could safely ignore (Ottoman Turkey and Bulgaria).

In practice this meant that the great majority of the 8,579 people interned during the war were destitute Austro-Hungarian working-class men. Most of them were Ukrainian, along with numbers of Poles, Croats, Slovaks, Slovenes, Czechs, Hungarians, Serbs, and others. Most of them were sent to remote camps and forced to do hard labour in appalling conditions. Their stories are covered in great detail in our other tours at camps like Banff, Kapuskasing, and Mara Lake.

6. Life in the Receiving Station

1913

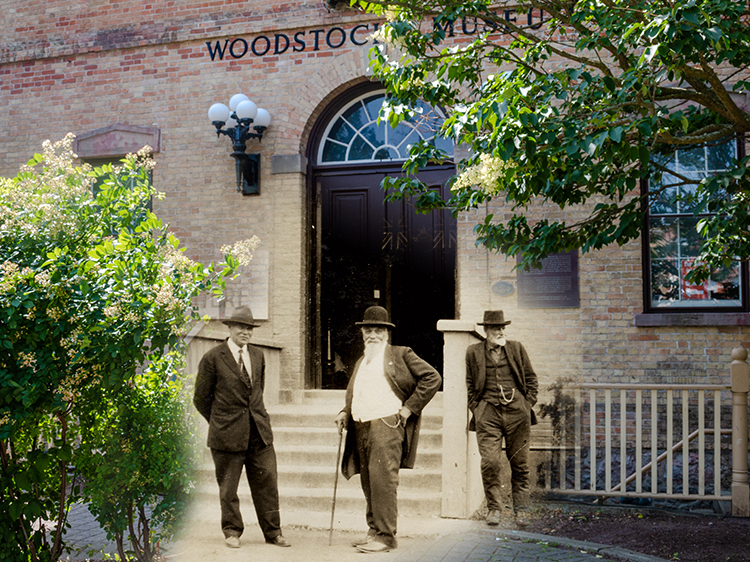

In this photo we see soldiers posing in winter uniforms outside the officers' quarters just a year before the war started.

Just a short distance from here the prisoners were housed in the privates' quarters of the West Block, which no longer stands today. The internees slept on cots spaced four feet apart in a large barracks room. They wore whatever clothing they were wearing when they were arrested, and were later given some additional clothes, especially for winter. Their food was supposed to be on par with that served to the soldiers garrisoned at the barracks, meaning they ate reasonably well. At this station they were not expected to work and generally just bided their time until transferred to another station.

As this was a huge military base, guards were not in short supply, and a new unit was rotated in every three weeks. There do not seem to be many reports of prisoner abuse—very much unlike the remote forced labour camps the second-class internees were destined for.

However, the internees had all their money and valuables confiscated upon internment. Around the end of 1915 thousands of dollars' worth of confiscated property was stolen. An investigation was launched but, "no one was charged in the matter as no records could be found."1 The internees had no recourse for this theft.

* * *

Across Canada's internment camp system, internees were to be given receipts for their confiscated possessions, so they could be returned upon their release. In practice these receipts were frequently not given out. At the end of the war the Receiver-General had $30,000 of confiscated cash left over that nobody could or would claim. That would be around $439,000 today.3

There was also the property forfeited as an indirect result of internment. Often those arrested and interned appeared to their family and friends to have simply disappeared off the face of the earth. They left behind traumatized loved ones, as well as jobs, homes, and possessions that would be snapped up by others.

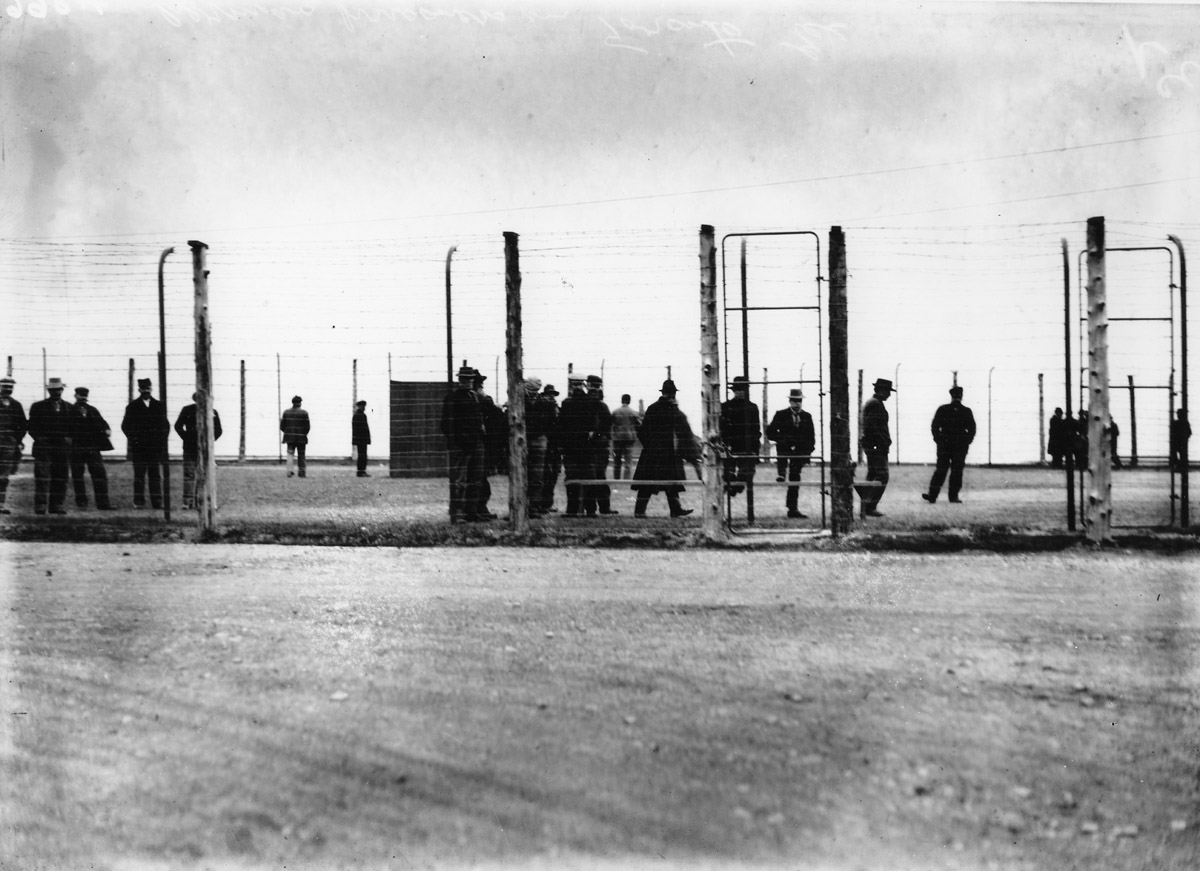

7. Arrested at Random

Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund

ca. 1915

We have come to the edge of the "prison yard" established for the internees roughly around this spot. In this image you can see around two dozen men milling about aimlessly behind the barbed wire fence. They appear to be in the clothing they wore when they were picked up off the street: One who is resting his foot on a bench looks like he is wearing a tie.

In most cases, the enemy aliens who found themselves in this camp were just going about their day when they were arrested. All it could take was a piece of bad luck or a chance encounter to lead to their abrupt disappearance into an opaque and uncaring camp system—sometimes for many years.

There were many episodes that illustrated the seemingly arbitrary and random way people came to be imprisoned here.

On a number of embarrassing occasions, citizens from Allied countries were interned by accident. A group of Russian Poles was arrested in Toronto and the court interpreter insisted they were Austrians because he said he could speak Russian and Polish, and he couldn't understand what the Poles were saying.

It turned out the interpreter could not actually speak Russian or Polish—he had been hired because he was British, and most of those who could speak those languages were enemy aliens and had been fired from their jobs. The furious Russian consul upbraided the Canadian foreign office, demanding they hire real translators: "a braying ass would do just as well in the position."1

* * *

The man shouted at the boys, who fled down the street. They told a passing police officer "That foreign Bohunk is after us!" Bohunk was a common slur for eastern European immigrants.

*The policeman approached me. 'Show me your foreigner's identification card.' I did not know what identification card he wanted me to show him… Being illiterate, and not reading newspapers, I did not know that I was to have such an identification card, that I was to carry it with me at all times, and that I was supposed to report to the town's police station periodically… I was thoroughly perplexed when immediately I was placed under arrest and taken away…

*Later, my employer farmer told me that when he came back to the wagon, he had to unhitch and re-hitch the horses. He waited, and waited for me to return. However, he had to give up waiting for me because time was running out for him to get back to his farm before sunset. He said that his first thoughts were that I had quit the farm to do something else. However, when he looked into the bunkhouse… he was surprised to see all of my things there with no evidence that I was not intending to come back…

Someone told him that on around the day I had disappeared, a number of new immigrants had been rounded up and sent away to internment camps… The farmer proceeded to contact the authorities to find out if I was among those that had been rounded up… He wanted to get me back to work on his farm. It took three months before I was released and sent back to his farm. I will always be very grateful to this farmer for his concern and effort on my behalf.1

Few internees would be as lucky as this man—though he still had his homestead confiscated as a result. Once someone was swept up in the system, its slow-moving, kafkaesque bureaucracy made it very difficult to secure release.

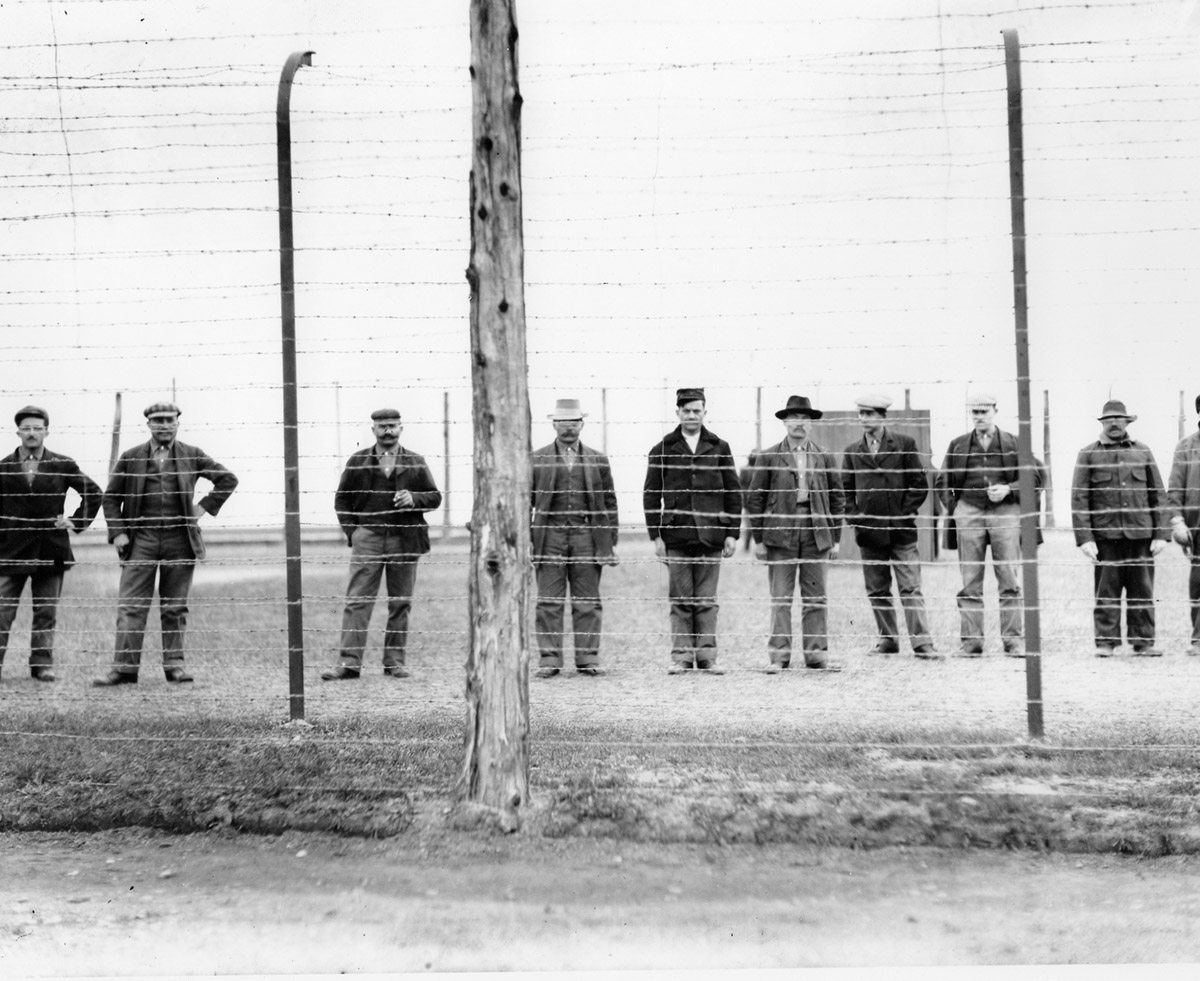

8. Brantford's "Turks"

Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund

ca. 1915

In this photo we see a handful of internees in the prison yard staring back at the photographer through the barbed wire. Being imprisoned in Stanley Barracks was a grinding and depressing experience. It was made all the worse because most of these men saw the governments of the enemy nations as oppressive foreign occupiers. Now they were being persecuted for the crime of being born under regimes that they had often come to Canada to flee.

The kinds of people interned were usually described in the press simply as "Germans," or "Austrians," but this flattens distinctions. This was most notably the case with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which contained a dozen different nationalities that were all so well-established that today each has their own independent nation-state.

This was also true of the Turkish-dominated Ottoman Empire. Though rapidly shrinking, by 1914 the Ottomans didn't just rule modern Turkey, but parts of the European Balkans and most of the Middle East. Under their domination were many different nationalities who chafed under Ottoman rule.

Over the course of the war the Canadian government claimed to have interned 205 people identified as Turkish.1 However, relatively few were ethnic Turks. Most were actually Armenians or Alevi Kurds who had immigrated from Ottoman territories to Brantford, Ontario. The Ottoman Empire's genocide of the Armenians in 1915 illustrates the profound unfairness of Canada's policy of categorizing all peoples from enemy countries as enemy aliens.

* * *

Their case offers a fairly typical example of how such colonies developed. In the 1890s, Harry Cockshut, a Brantford-based farm equipment manufacturer, went on a business trip to Constantinople and met some Armenians. He invited them to Canada to work in his factory. By 1914, several hundred Armenians and their neighbours, who were Alevi Kurds, had settled around Brantford, primarily to work in his factory.2

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers on October 31, 1914. The police wasted no time, and on November 10 launched a mass raid on Brantford's "Turkish Colony," arresting 120 men. This was done because of the "reception of anonymous threatening letters, supposedly from Turks," wrote the Toronto Globe.3 Today, it seems likely the letter was sent by someone who wanted these people removed from their scarce, coveted jobs.

Before being sent to Stanley Barracks, the Globe writes the "Turks" were kept in the county jail, "in very cramped quarters… they had hardly enough room to lie down." The prisoners immediately went on hunger-strike and "refused to eat the Armenian bread," they'd been offered. The article implies the hunger-strike was because they were Turks who were insulted by being offered Armenian food. In reality they were Armenians who were probably protesting the injustice of their treatment.4

Once brought to Stanley Barracks, one of these unfortunate men died in an "unusual and disturbing incident." After the medical officer was interviewed, his death was blamed on "pneumonia."5 The remainder would later be transferred to other camps across Canada—most to Fort Henry in Kingston, and then Petawawa to do hard labour.

9. The Legacy of Hatred

1933

Here we see riders of the Royal Canadian Dragoons doing the "Extended 4s" manoeuvre during a musical ride.

After two years of war, Canada was running out of men. They needed more labourers on the home front to work in strategic industries—jobs that could be done by the internees. Canada also desperately needed the hundreds of soldiers guarding the internees in France, where they could replace the tens of thousands of dead and wounded.

Over the course of 1916 the government began paroling the "non-dangerous" prisoners to go work in strategic industries. Stanley Barracks gradually emptied as arrests declined. Those few prisoners who were deemed "dangerous" were sent to a small number of remote camps.

The freed internees were not welcomed back into society. The patriotic fervour that led so many Torontonians to suspect their foreign neighbours of being spies or saboteurs, became hardened and embittered by the long years of war.

During the Conscription Crisis of 1917, many loudly argued that if Canadian men were being conscripted into the army, then enemy aliens should be conscripted to forced labour camps. The Wartime Elections Act of 1917 stripped voting rights from all enemy aliens—controversially even from naturalized citizens.

For many, this did not go far enough. Angry veterans returned from the war, raided Toronto businesses that employed enemy aliens, rounding them up and demanding they be interned. In August 1918, the military struggled to restore order as 200 veterans and thousands of sympathizers went on a two day rampage, destroying foreign businesses and beating up enemy aliens they found. The City of Toronto, along with many other organizations, passed resolutions demanding the deportation of all enemy aliens after the war.1

* * *

Today we recognize that this sounds perilously close to the language of genocide.

For the hundreds of thousands of enemy aliens who lived in fear throughout the war, the situation was becoming "unbearable." Many gave up on Canada entirely. The Ukrainian Presbyterian community of Toronto asked the government to end the ban on enemy aliens leaving Canada, so they could "depart in peace."3

When the finally war ended and the ban was lifted, thousands did leave. In 1920, the Bassano Mail wrote that 15,000 had left Ontario since the end of the war, including 5,000 from Toronto. These included 10,000 Austrians, 2,000 Greeks and Rumanians (those were Allied countries but still described here as enemy aliens), 2,000 Bulgarians and Serbians (Allied), and 1,000 Macedonians. The report noted acidly that they were taking an estimated $30,000,000 with them. "They were for the most part men who filled the places in the industrial world when Canada's sons enlisted."4

For those who stayed, the nightmare would continue for generations. Sandra Semchuk's book The Stories Were Not Told, recounts the experiences of dozens of internee descendants. They grew up surrounded by a pall of shame thanks to these events, which nobody in their family ever wanted to discuss. Their parents and grandparents lived the rest of their lives in constant fear of the government and society turning on them again, and often taught their children to stay vigilant and keep a low profile. As children they themselves faced discrimination in schools and in jobs.5

Their stories make it clear: The legacy of these events echo down through the generations.

Endnotes

1. Toronto in 1914

1. Stephanie MacLellan, "Cheers break out in Toronto as Britain declared war on Germany in 1914," *Toronto Star*, August 4, 2014, online.

2. Pierre Berton, Marching as to War, (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2001), 131.

2. The Hysteria of 1914

1. "Kaiser is Mad Say Toronto Germans," *Toronto Daily News*, August 18, 1914, online.

2. "Foreigners in Toronto," *Toronto Daily Sun,* August 20, 1914, online.

3. "Articles: Toronto, ON," *Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund,* online.

3. The Internment System

1. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 21.

2. Kordan, 30.

3. Kordan, 84.

4. Kordan, 199.

5. Kordan, 93.

4. The Canadian National Exhibition

1. Aldona Sendzikas, *Stanley Barracks: Toronto's Military Legacy,* (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2011), 98.

2. Sendzikas *Stanley Barracks*, 99.

3. Sendzikas *Stanley Barracks*, 103.

4. Aidan Wallace, "Our Warriors: Celebrating the 98th Warriors Day Parade," *Toronto Sun,* August 17, 2019, online.

5. The Receiving Station

1. Sendzikas *Stanley Barracks*, 110.

6. Life in the Receiving Station

1. Sendzikas, *Stanley Barracks*, 113.

2. Sendzikas, *Stanley Barracks*, 113.

3. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 168-169.

7. Arrested at Random

1. Kordan, 126.

2. Sandra Semchuk, *Their Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps,* (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019), 127.

8. Brantford's "Turks"

1. "A Group Biography of the 'Turkish' Internees of Brantford," *Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund, (2011), online.

2. "A Group Biography of the 'Turkish' Internees of Brantford," online.

3. "Turkish Colony Raided: Hundred Twenty Taken," *Toronto Globe*, Nov. 10, 1914, online.

4. "Turks Refuse to Eat Armenian Bread in Jail," *Toronto Globe, Nov. 11, 1914, online.

5. Sendzikas, *Stanley Barracks*, 113.

9. The Legacy of Hatred

1. Kordan, 248.

2. Lubomyr Luciuk, *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920,* (Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001), 38.

3. Kordan, 248.

4. "Aliens Leaving Ontario," *Bassano Mail,* May 13, 1920, online.

5. Semchuk, 132.

Bibliography

Berton, Pierre. *Marching as to War.* Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2001.

Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund. "A Group Biography of the 'Turkish' Internees of Brantford." 2011. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1PzNX1lgGb6LLYBWFxqZYuaVQkn14KncpoxcvgwJoIjE/edit

Kordan, Bohdan S. *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience.* Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Luciuk, Lubomyr. *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920.* Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001.

Sendzikas, Aldona. *Stanley Barracks: Toronto's Military Legacy.* Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2011.

**Newspaper Articles**

MacLellan, Stephanie. "Cheers break out in Toronto as Britain declared war on Germany in 1914." *Toronto Star*. August 4, 2014. https://www.thestar.com/news/world/ww1/2014/08/04/cheers_break_out_in_toronto_as_britain_declared_war_on_germany_in_1914.html

Wallace, Aidan. "Our Warriors: Celebrating the 98th Warriors Day Parade." *Toronto Sun.* August 17, 2019. https://torontosun.com/news/local-news/our-warriors-celebrating-the-98th-warriors-day-parade

"Aliens Leaving Ontario." *Bassano Mail,* May 13, 1920. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/11/1920-05-13-BASSM-Aliens-Leaving-Ontario.pdf

"Foreigners in Toronto," *Toronto Daily Sun,* August 20, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/11/1914-08-20-TDS-Foreigners-in-Toronto.pdf

"Kaiser is Mad Say Toronto Germans," *Toronto Daily News*, August 18, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/11/1914-08-18-TDN-Kaiser-is-Mad-Say-Toronto-German.pdf

"Turks Refuse to Eat Armenian Bread in Jail" *Toronto Globe, Nov. 11, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/11/1914-11-11-GLOBE-Turks-Refuse-to-Eat-Armenian-Bread-in-Jail.pdf

"Turkish Colony Raided: Hundred Twenty Taken," *Toronto Globe*, Nov. 10, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/11/1914-11-10-GLOBE-Turkish-Colony-Raided-Hundred-Twenty-Taken.pdf