Walking Tour

A Stroll Down Queen Street

The Rise of Sault Ste. Marie

Alexa Dagan

Much of Canadian history was built on the banks of its rivers. For Sault Sainte Marie, St. Mary's River first served as a major fishing river, with innumerable schools of whitefish leaping over the river's once turbulent rapids. From there, it was a major shipping highway of the fur trade, which led naturally into its current role as one of the world's busiest shipping channels.

From its early days as a rough and tumble fur trade post, to the town's meteoric rise as the industrial heart of northern Ontario, to a charming Victorian community, Sault Sainte Marie has repeatedly been reincarnated by a series of complex and exceptional individuals who never failed to perceive and encourage the little town's unlimited potential.

Follow us on a stroll down Queen Street as we use some of the city's oldest buildings as windows into Sault Sainte Marie's colourful past.

This tour starts on Pim Street, where we can explore the Ermatinger Clergue National Historic Site and uncover Sault Sainte Marie's fur trade routes and view the homes of some of the city's earliest pioneers and developers. From there we turn left onto Queen Street East, and arrive at the Algonquin Hotel where we leave the fur trade era and learn about Sault Sainte Marie's increasing connections to the world around it.

From there, the tour continues straight down Queen Street, with several stops along the way exploring themes such as the role of the Catholic Church in the young community, the everyday lives of Victorian Ontarians, Sault Sainte Marie's development from community to city, the role of the city's Italian immigrants, before finally ending at the GFL Memorial Gardens for a brief reflection on Sault Sainte Marie's legacy of producing some of the country's most extraordinary, talented, and driven people, as well as its contributions to Canadian history since the city's earliest days.

This project is a partnership with the Sault Ste. Marie Downtown Association, the Sault Ste. Marie Museum, and Tourism Sault Ste. Marie.

1. The Fur Trade Era

1887

The Ermatinger Stone House was built by the fur trader Charles Oakes Ermatinger between 1814 and 1823. It is the oldest stone house in Canada west of Toronto.1

When Sault Ste. Marie was just a tiny and remote fur-trading post, this imposing stone home dominated the landscape, and it became a hub of social activity in the community. Throughout its history it served as a home, mission, hotel, tavern, courthouse, post office, dance hall, tea room, and apartment building. Finally in 1965 it became a museum, a role it continues to fulfill today as part of the Ermatinger Clergue National Historic Site.

* * *

The first French Jesuit missionaries to arrive here in 1641 were met by 2,000 people, an astonishing gathering of First Nations peoples. They came from "as many as a dozen different groups visiting the spot from as far afield as Lake Winnipeg and the 'North Sea'"--meaning Hudson's Bay. The Jesuits were awed by "the convenience of having fish in such quantities that one has only to go and draw them out of the water."2 They called the place the Saint Mary's Rapids, which translated to Sault Ste. Marie.

A slow trickle of French missionaries and fur traders followed over the next century, preaching to and trading with the Saulteaux. The number of French here was never very large, and they established a small post on the southern side of the rapids. After the Fall of Quebec in 1759 during the Seven Years War, French North America passed into British hands, and shortly after a British party arrived to take over the trading post.

This heralded a new period in Sault's history to which Ermatinger's house belongs. A growing stream of fur traders rowed as far west on the Great Lakes as they could before reaching Bawating, where they portaged their canoes to Lake Superior. Fierce competition between the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company (NWC) over control of Canada's fur trade drove the NWC to establish a major trading post on the north side of the river, just opposite the rapids two kilometres west of this spot.

By 1812, it is recorded that 15 European families called Sault home, along with much larger numbers of of Saulteaux and Metis. Charles Ermatinger's family was Metis: He had married an Ojibwe woman, Charlotte Cattoonaluté, and with her had 13 children (tragically, 4 or 5 of them died in infancy).3

As one can deduce from the size of his house, Charles Ermatinger was a hugely successful fur trader. Son of a Montreal merchant, he started working for the NWC in 1795. He was well-liked and respected among the community's rugged inhabitants. According to one source, Charles was "ready of wit, rough in manner, a shrewd trader, never lacking in hospitality, kept open house for all who came."4 These were all traits essential to survival in the unforgiving fur business.

Fur traders ranged deep into the Canadian wilderness, sometimes travelling thousands of kilometres. They navigated the country's extensive--and often uncharted--waterways in birchbark canoes or York boats, carrying with them bales of furs, trade goods, and everything they needed to survive.

The work was exciting and highly lucrative, but with every foray into the wilderness traders faced isolation, hunger, a brutal climate, dangerous wildlife, and rival fur traders. Ermatinger himself had a close brush with death when he and a fur trade companion found themselves lost in the backcountry. After sixteen days in the woods, Ermatinger emerged--haggard, but alive. His companion was never seen again.4

Ermatinger became an important figure in the community and was appointed a justice of the peace in 1816. He continued expanding his fur trading operations, and started farming the large acreage around his home. When his great stone house was finally completed in 1823, it was admired by the rest of the community and, one fur trader remarked, it "did much credit to his good taste."5

His death in 1833 was deeply felt by Sault's inhabitants. His biographer Myrom Momryk writes, "In his life he had witnessed the end of the independent fur trader and the arrival of an era when large corporations influenced decisively the economic life of the colonies."6

2. Life in a Trading Post

1900s

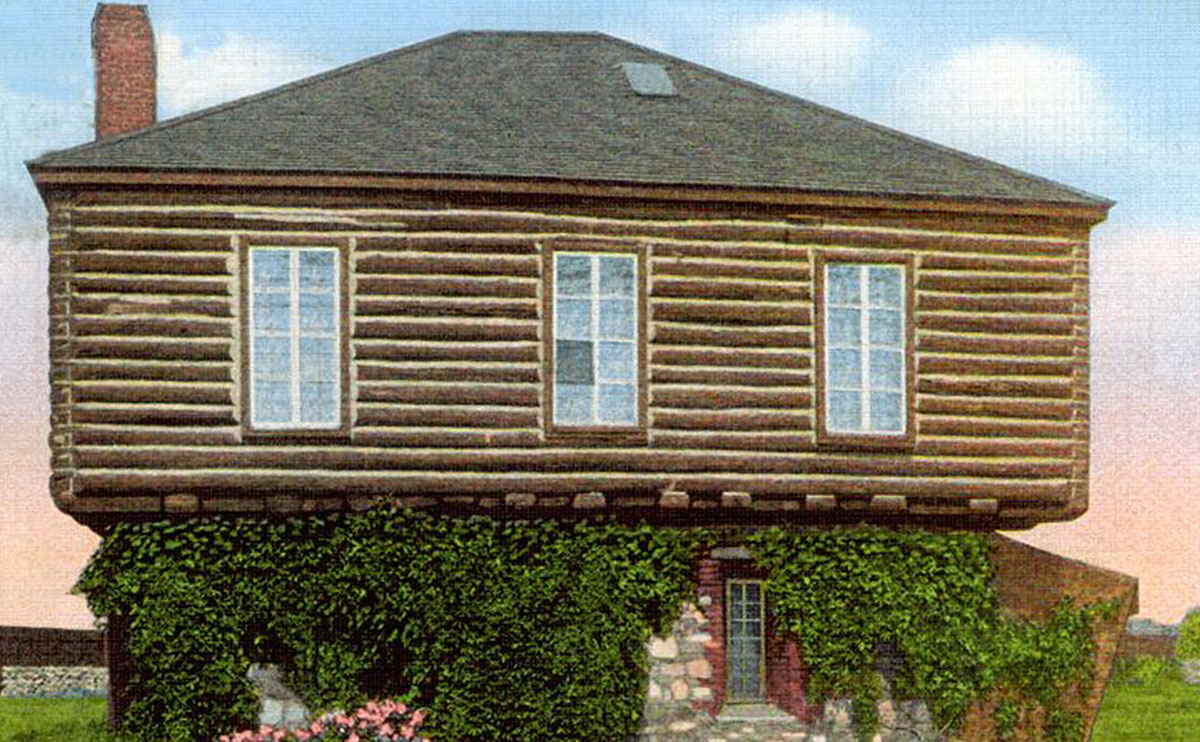

The lower half of the mushroom-shaped Blockhouse, built in 1819, is one of the only remnants of the original North West Company fort that birthed the city of Sault Ste. Marie. Originally, the structure was a single storey and served as the powder magazine. A windowless, single room affair, the building had loopholes--small gun ports--at intervals along the stone walls so that it could serve as a last refuge in case of attack.

As the fur trade declined in importance, the building fell into decay. Then, nearly 80 years later, it was restored and a second storey added so that it could the living quarters of Francis H. Clergue. He chose the spot because it was conveniently close to the paper mill he was building just next door. Clergue had the loopholes plastered over: By then Sault Ste. Marie had changed much, and it was quite unlikely they would ever be used for their intended purpose.

The building survived at its original location long after Clergue's departure from Sault Ste. Marie. Finally in 1996, when the mill planned an expansion, it was relocated here beside the Ermatinger Stone House. Together these two buildings are symbolic reminders of Sault Ste. Marie's long fur trade history.

* * *

Importing supplies was expensive, so most food had to be acquired locally. But the land was abundant enough there was never much threat of starvation at the trade post. They grew potatoes, raised pigs, and drew the abundant whitefish from the rapids. One trader proclaimed Sault's whitefish were "the richest and best flavoured found in fresh water."1 Bread was made from a local strain of maize first cultivated by the Ojibwe.

While the community had a strong catholic presence, the increasing British presence led to the arrival of an Anglican priest in 1821. For the Anglicans in the fort, this was a welcome development--not just for their souls, but also to distract from the boredom. Unfortunately, he didn't turn out to be as engaging as they'd like.

It is related how on one occasion a deputation of laymen travelled to the Bishop to complain about this minister's monotonous preaching, claiming the same dry sermon had been inflicted on them three consecutive Sundays.

"'You don't tell me that?' exclaimed His Lordship, 'what was the text?'

"The deputation was speechless, for none remembered it.

"'Well, what did the man say?' asked the prelate. Again there was silence, for none could recall the subject of the sermon.

"'I think,' suggested Dr. Strachan (the Bishop), 'you'd better go home and I shall write your clergyman to preach the sermon again in order that you may get to know its contents."2

By 1843 the HBC had largely refocused its trade routes on Hudson's Bay, eclipsing the trade network around the Great Lakes and reducing the Sault's economic importance. Sault became a quiet provisioning stop for those moving west or east along the lakes. While the town was accessible by ship in the summer, the freezing of Lake Superior in the winter complicated any kind of large scale shipping operations. The town also lacked any municipal structure, or judicial system until 1858, making it risky for potential settlers.

The completion of a branch of the CPR from Sudbury to Sault Ste. Marie in 1887 resolved many of the accessibility issues faced by the remote community, and Sault incorporated as a town that same year (it had incorporated as a village in 1871). Now much more appealing to prospective settlers, the town began to grow steadily.

One of these settlers was the businessman Francis H. Clergue, who is now recognized as one of the galvanizing forces behind the town's vault into the industrial era. It is somewhat fitting that Clergue chose to make the old powder magazine his home: He directed the town's next phase while firmly ensconced in the most distinctive survivor of the previous.

3. The Tides of Change

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.17.12a

1890s

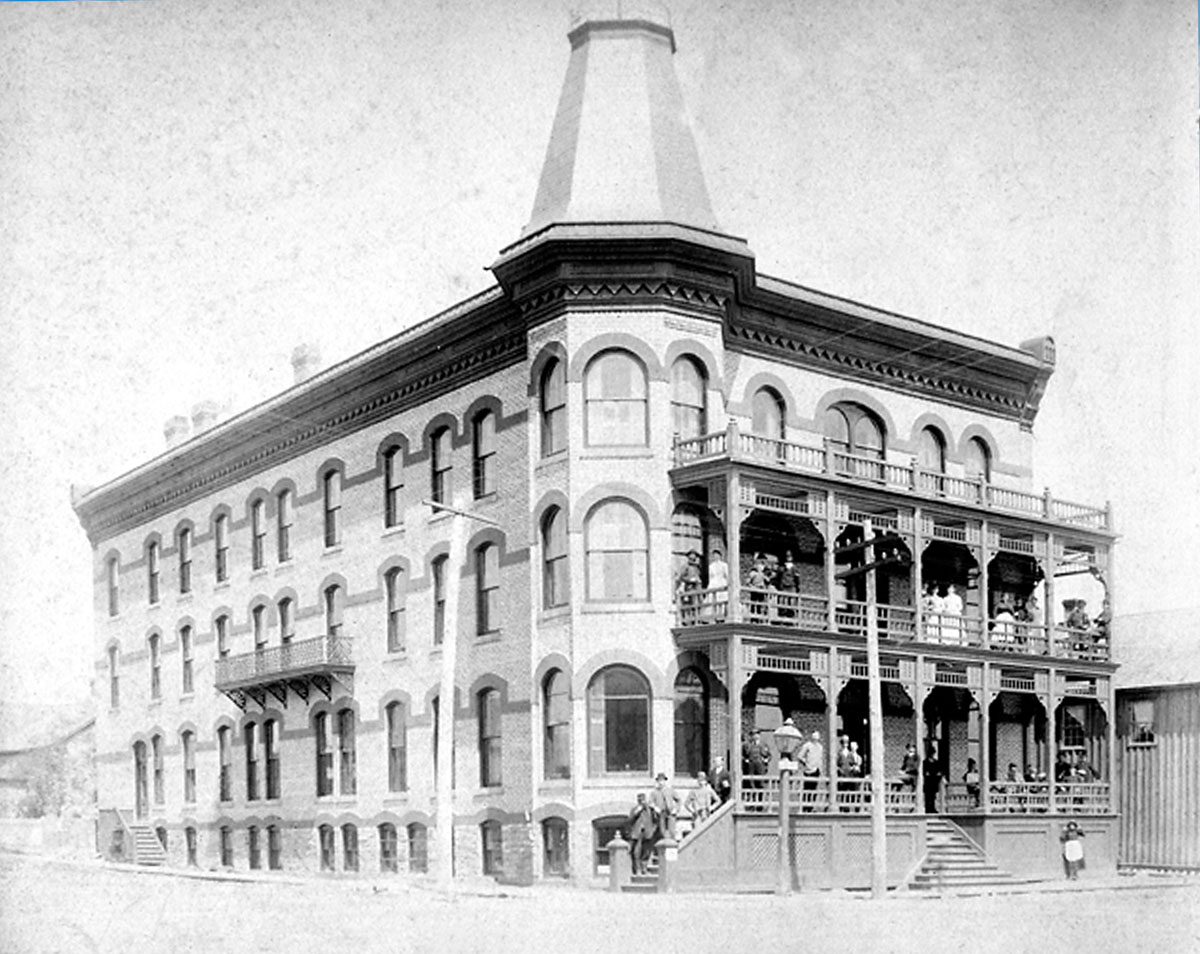

This is the Algonquin Hotel, a fine example of late 19th Century Victorian hotel architecture. It's distinctive by its brick construction, arches over the windows, and of course the distinctive octagon-shaped turret on the corner just facing you.

As in most Canadian towns, the arrival of the railway was a dramatic and transformative event that reshaped Sault Ste. Marie almost overnight. The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) line to Sault Ste. Marie was completed in 1887, and the Algonquin Hotel went up the next year to house the many settlers, workers, tourists, and businesspeople who began streaming into town.

Not everyone was happy about these changes however. As sleepy as early 19th Century Sault Ste. Marie may have seemed, many old-timers resented the disruption of their quiet lives by the sudden influx of money and settlers.

None had more reason to fear these developments than the Saulteaux First Nations, who had lived here for millennia, and had by then been confined to a reservation on Whitefish Island in the rapids (and even that land would soon be stolen from them for industrial activity by Francis H. Clergue).1

* * *

In 1846 there were only around 500 people in Sault Ste. Marie; mostly a skeleton crew of HBC employees, along with a number of French-speaking Metis, and Saulteaux FIrst Nations.2

When travel writer William H. G. Kingston visited in the 1850s, he commented on the comfort and warmth of the log houses, and also remarked on the growing tourist industry and the "several hotels, which are resorted to in summer by visitors from both the States and Canada, who go there to enjoy the cooling invigorating breezes from Lake Superior."3

Although still a small, isolated community, Sault Ste. Marie found itself becoming increasingly known to the outside world--and some inhabitants didn't like it. One HBC employee bemoaned the great efforts they'd made mapping the region, and how those same maps would only serve to draw more people into the region:

"It may be politic on the point of the company to place before the rest of the world their exertions in adding to the known geography of our planet but I fear their endeavours to this respect will tend to curtail our dividends and these hyperborean regions are now becoming so well known to the civilized world that, old as we are, I should not be surprised if we lived to see these regions becoming as fashionably a summer resort to the travelling community as Saratoga and Chelenham now are."4

Others romanticised the pastoral simplicity of the fur trade era and resented the imposition of 'civilization' on their remote corner of the world. Writing in 1904, Edward Capp, one of Sault's first historians, interviewed old timers who had survived from those fur trading days:

"Men who lived before the town took so lately its sudden leap into prominence sigh for the 'good old times' that preceded these present... but old folks, whose age is measured at the four scores and over [80 years], sit by the fire of a Winter night with their progressive grandchildren about their knees, and as they recall from the past sweet memories of their own childhood and youth in the (to us) misty years of the nineteenth century in Sault Ste. Marie, even these whose heads are bowed with the snows of many winters, think and speak longingly and lovingly of those times and feel that such a measure of happiness and contentment as they knew then will not again be theirs until the final journey has been taken, and they, at last, have entered the Blessed Ish-pem-ing (heaven)."5

Regardless of how some residents of Sault Ste. Marie felt about the era that was then dawning, there was little they could do to stop it. Now that the railway and steamships made access to the outside world cheap and easy, global investment capital could begin to flow into the town, and there was no shortage of people willing to take full advantage of it.

4. The Catholic Legacy

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2008.4.49

c. 1877

This is Precious Blood Cathedral, the oldest surviving church in Sault Ste. Marie and an important reminder of the persistence of French influence in the town. It was built in 1876 in the Gothic style popular in francophone Canada at the time.

It was of course not the first Catholic church here; a small wooden church was built on this same site as early as 1846, and Jesuit missionaries had been proselytizing the Saulteaux and Metis as far back as 1641. As Sault Ste. Marie became increasingly anglophone and protestant over the following centuries, the town's European roots lie with the Jesuit missionaries and French voyageurs who began the fur trade.

* * *

Nevertheless the Catholics ardently persevered. In the first half of the 19th century, the Jesuits still undertook active missionary work, travelling between First Nations villages and fur trade posts by dog sled and snowshoe, often in dire winter weather. While the First Nations met much of these efforts with resistance or indifference, later missionaries still found a small yet active Catholic presence among the First Nations and Metis community in and around Sault Ste. Marie.

In 1847, a Jesuit missionary wrote to a counterpart regarding his hopes for the community's future:

"When I imagine how in the near future the population of Sault-Ste-Marie will have increased tenfold, and the shores of the great lake likewise inhabited by people working in the rich and numerous mines that are being discovered every day and are being developed, I say to myself, I hope that some new helpers will soon be arriving from Europe and that our holy religion might one day begin to flourish in this remote outpost which – even at present should be the centre of religious establishments, as it is already for commercial communications and transactions!”2

At the same time, after nearly two centuries of travelling priests and religious services held in log cabins, the Sault's Catholics finally had a permanent place of worship: a small wooden church was built on the site in front of you, where the great sandstone Sacred Blood Cathedral stands today. The church fulfilled its role, but by the 1870s it had developed a worrying lean and was propped up by wooden planks.

Fortunately, construction on the Cathedral to replace it began just in the nick of time. Building the church was a community effort. It was made from sandstone sourced from the excavation for the Wietzel Lock on the American side of the river, and the stone was physically hauled in carts across the frozen river to the Canadian side. These efforts, and much of the church's construction, were conducted by community volunteers.

The Precious Blood Cathedral, still stands as a monument to Sault Ste. Marie's transition from frontier outpost to industrial town. When it was completed it's tall spire dominated the landscape and anchored the growing community around a geographic centre.

5. Entering the Modern Age

Sault Ste. Marie Museum E996.3.7

1910

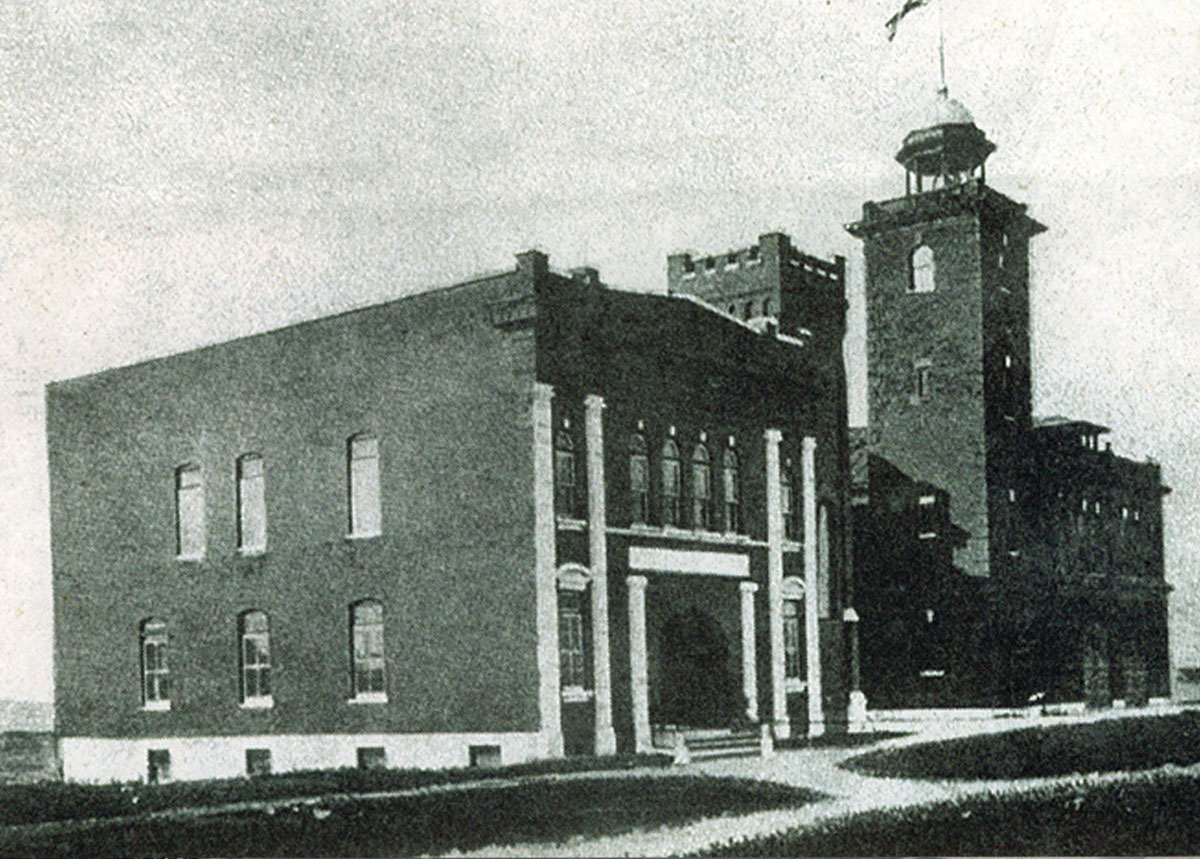

The building you see here was once the town's municipal hall complex. It may look like two buildings, but it was actually a single one with multiple wings. Built in 1903, it housed the Carnegie Library, town hall, and fire hall.

As the Sault grew, so did its tax base--and the expectation of its citizens for the trappings of modern life we take for granted today. Public buildings like these were symbols of modernity and gave residents access to books, fire protection, mail, and civil bureaucracy. Local government, with the help of private business, brought about many improvements in the lives of Sault's residents in this period, including sidewalks, telephones, electricity, paved roads, and streetcar lines. The Sault we would recognize today was starting to take shape.

As for the municipal complex, it didn't last particularly long. In an ironic twist of fate, the complex housing the fire brigade burned down just four years after it was built. The fire was so severe that firefighters from the American Sault Ste. Marie rushed over to help--but to no avail.

* * *

Sault Ste. Marie's growth in the late 1800s was truly remarkable. The Hudson's Bay Company officially closed their trading post in 1869, but the town didn't have to wait long for new investments to fill the void and draw in new settlers.

The fur trade had put Sault Ste. Marie on the map, and the ship canal built on the American side in 1855 caused maritime traffic on Lake Superior to skyrocket, from which both the Canadian and American Sault Ste. Maries' benefited. The rich mineral deposits of northern Ontario, and the town's strategic location at the eastern end of Lake Superior, ensured future prosperity.

Between 1881 and 1901, the population of Sault Ste. Marie grew almost ten-fold to 7,169.3 The population increase set in motion a boom of construction as government officials and businessmen hastened to erect houses, banks, hotels, churches, schools, and stores, that met the growing demand for every kind of good and service. The local government, with an elected revee (mayor), councillors, and appointed civic officials, scrambled to keep the town running smoothly.

Not all their efforts met with success. Seeing their counterparts in the American Sault Ste. Marie harness the rapids for hydroelectric power, a consortium of businessmen banded together to build their own hydropower project in the early 1890s. Unfortunately the main power channel collapsed, and then the consortium ran out of money. The town took over the half-completed project, along with a massive $263,000 debt.4 They had no electricity to show for it.

Fortunately for Sault Ste. Marie, Francis H. Clergue was about to come to the rescue.

6. Supercharging a City

1914

This photo shows a company of Sault Ste. Marie soldiers posing for a photo before going overseas to fight in the First World War. The imposing stone buildings on either side still stand today, reminders of Sault's rapid development in the twenty years before the war.

On the left is the old post office. When it was completed the clock tower towered over the middle of Sault Ste. Marie--although it an actual clock wouldn't be installed for six years. When the post office first opened its doors it was considered such an important event that the Sault Star reported how one C. James Pim swaggered into the building unannounced, "fat and sassy," demanding to be the first person to mail a letter from there.1 In 1949 the post office was moved to a more modern building, and this building converted into government offices.

On the right is the Dawson Block, built in 1898. The distinctive red sandstone is the same as that from the Sacred Blood Cathedral, coming from the construction of the Canadian Canal at Sault Ste. Marie. The bottom storey now houses a sports bar, but for much of its early history it was home to Dawson Grocery and with the Oddfellows Hall on the second storey. You'll also notice that the building used to have a third floor for apartments. Unfortunately, in 1953 a devastating fire on that floor wrought so much damage it was easier to get rid of the third floor instead of repairing it.

With the basic municipal structure and necessities taken care of, capitalists like Francis H. Clergue, John Dawson, and William H. Plummer saw opportunity in Sault Ste. Marie's empty streets. They funded impressive stone buildings to house hotels, shops, apartment blocks and offices. Among Canadian cities Sault Ste. Marie has a particularly impressive stock of well-preserved heritage buildings from this period (even if some like the Dawson Block survive in somewhat reduced form).

For savvy capitalists, launching a commercial enterprise in the newly opened parts of Canada was a huge gamble: they could pay off massively and lead to business empires that survive to this day, or they could meet with failure and disgrace (much, much more common).

Seen through this lens Francis H. Clergue is an almost uniquely fascinating case. History remembers him as the business tycoon who pretty much founded Sault Ste. Marie's industrial economy, but before he'd ever set foot on the banks of the Sault he'd already lost millions in at least 14 failed business ventures from Alabama to Iran.2 And though he would leave a towering legacy in this city, he departed it more or less in disgrace at the middle of his career.

* * *

He tried his hand in all sorts of fields, from ocean liners and tourist resorts, to mining and land speculation. Later in life, one scheme to sell artillery shells to the Russian Czar fell through spectacularly when the factory blew up and then Bolshevik revolutionaries deposed the imperial government.

As his biographer, Edward Alan Sullivan writes, Clergue had “the courage of ignorance,” which “nerved him to attempt that at which a purely technical man would have hesitated, while his persuasive qualities drew others to follow his ventures.”3

After a truly spectacular string of failures, Clergue arrived in Sault Ste. Marie in 1894, and his luck quickly began to turn around. He saw the potential of the failed hydropower project the town now owned, and bought it from the government. The next year, the hydropower project was completed and produced enough electricity not just for the city, but a pulp mill which he also established.

He moved into the blockhouse (seen on Stop 2), to oversee the pulp mill and had his employees harvest the vast reserves of spruce in the surrounding regions. It was the first major industrial enterprise in the city--and it was only the beginning. In the years that followed he set up iron ore and nickel mines, railways, and fleets of steamers to move raw materials to Sault Ste. Marie, and in 1901, began building the vast Algoma Steel Company complex. All of these and his other enterprises were put under his umbrella company, the Consolidated Lake Superior Company (CLSC), which was valued at $117 million ($4 billion today).4 He needed thousands of workers, and it was not long until they came.

His expansive vision dazzled those around him, but the pursuit of so many simultaneous ventures spread his company's resources thin. Most of his various businesses failed to turn a profit, a fact the fast-talking Clergue was successful in painting over for a long time.

In 1903 his luck ran out (again). His companies could no longer meet payroll and unpaid lumberjacks and construction workers rioted outside his head offices on Huron Street. Companies of militia were even dispatched to Sault to quell the unrest, though the situation had calmed down by the time they arrived.

Clergue finally acquired bank loans to pay off his employees, but his mystique had been shattered. The government, who Clergue had convinced to heavily subsidize his projects, worried he was too big to fail and him out on the condition that his companies were put them under new and less erratic management.

Clergue himself left the town he helped build and moved on to his next great venture.

Many of his ventures survived under government management and continue to survive to this day.

7. Conquering Public Health

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 982.68.8a-b

1909

A large group of labourers stop and pose for a photo during the digging of sewer lines on Queen Street in front of the offices of the Soo Evening News.

The explosive population growth in the final years of the 19th Century meant Sault Ste. Marie faced many of the same problems as industrial cities across Europe and North America at this time: overcrowding, unsanitary conditions, and frequent outbreaks of epidemic disease.

Surmounting these challenges was a triumph of organization and modern public health. One of the most crucial solutions was the construction of vast sewer systems like the one you see here. Perhaps just as important was the founding of a modern medical system, represented by the 1899 opening of a hospital by the Catholic order of nuns, the Ladies of the Grey Cross.

* * *

For much of the 19th century, it was common practice for physicians to use the same unsanitized tools on multiple patients, wear the same clothes between the office and the operating theatre, and even to hold one's scalpel between their teeth when both hands were needed in surgery. These practices which seem so horrifying to us today, were disappearing by the time Sault Ste. Marie had become an industrial town.

By the end of the century dramatic advances in medical science were revolutionizing hospitals: Joseph Lister's Germ Theory was well known, surgical anaesthesia and X-rays available, and doctors could even detect certain ailments through blood and urine testing .2 It was becoming increasingly common for people to seek medical attention in a hospital, rather than to summon a private physician to a home, and in the case of infectious diseases, health and civic officials were quicker than ever to enforce quarantine measures.

While these advances increased the effectiveness of medicine, they worked best in a hospital environment. Unfortunately, the town lacked the money to build a public hospital, and no private citizens stepped forward to donate the funds. Even the federal government rejected requests for assistance. Sault Ste. Marie was on its own.

The town's representatives sought advice from T. F Chamberlain, the official responsible for inspecting Ontario's asylums and prisons, and he offered the town a piece of advice: "If you wish for a hospital of which the work is serious and lasting, ask the Grey Sisters."3

The Grey Nuns of the Cross were a Catholic order dating back to New France that established charitable hospitals from Manitoba to Ohio. When Sault Ste. Marie called upon their aid they rose to the challenge. The new hospital was completed in 1899, and when the doors were opened, it was a cutting-edge facility with the latest medical equipment such as a pathology lab, X-ray machine, research labs, and areas for quarantine.

Today, Sault Ste. Marie's General Hospital is the direct descendant of the original hospital built by the Grey Nuns.

8. The Premier from the Sault

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 991.176.1

1910

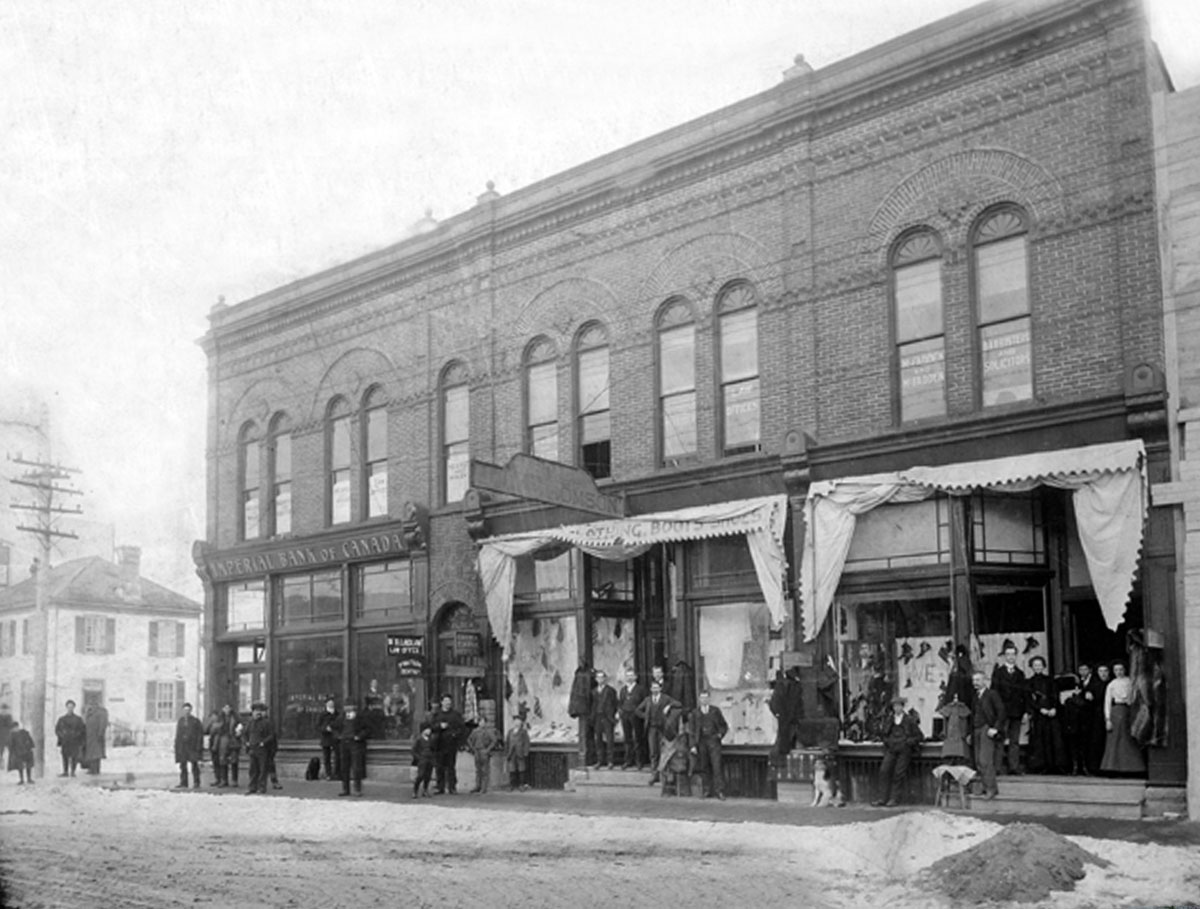

In this photo we can see a crowd of people posing in front of the Ganley Block, which housed the Imperial Bank of Canada and some other stores. It also was home to William Howard Hearst's law firm, Hearst, MacKay and Darling.

Hearst was born in Bruce County in 1864 before moving here to practice law, and serve as chief of the volunteer fire brigade. In 1908 he was elected to represent Sault Ste. Marie in the provincial parliament for the Conservative Party. In 1914, as the world was roiled by the First World War, Premier Whitney died in office and Hearst was sworn in to replace him.

As premier from 1914 to 1919, he saw the province through the traumatic war years, and left an indelible mark. He was always a zealous booster of northern Ontario's development, and loyal to the interests of Sault Ste. Marie. When an academic report was skeptical about the feasibility of northern development, Hearst angrily denounced it, saying "With all due respect to the gentleman mentioned, I know a great deal more about Northern Ontario than any professor in the country."1

* * *

So it's hardly surprising the people of Sault were thrilled when he was appointed premier. The Sault Star reported "Every man in Algoma takes Mr. Hearst's election as a personal compliment." Even his political foe, the head of the local Liberal association, said ""I think [the Conservatives] have made a good choice, and I am pleased that the new Prime Minister (of Ontario) is a man from Northern Ontario."1

Some of his first acts reflected his northern Ontario roots: reforestation and wildfire fighting services were established in Ontario in this time. Coming from the industrial centre of Sault Ste. Marie, he saw the need for better protections for factory workers, and established the Department of Labour, which sent out inspectors to investigate safety complaints, ensure labour standards were strictly enforced, and set up Ontario's first workers' compensation program.

He saw that Ontario became the first province to enact Prohibition, and established the Child Welfare Bureau. Under his leadership, women got the right to vote in Ontario in 1917, and he pushed through the Chippewa Project on the Niagara, at the time the world's largest hydroelectric dam.

He was also a strong supporter of conscription, an issue that brought about the greatest unity crisis in Canada's history. Hearst's conscription position alienated Ontario's farmers (50% of the population at the time) and in the election of 1919 his Conservative Party was soundly defeated by the United Farmers of Ontario.2

Hearst went on to a long career on the International Joint Commission solving boundary disputes between Canada and the United States, and he was knighted by King George V for his efforts during the war. He died in 1941 in Toronto.

Sault Ste. Marie has always been proud of Hearst's legacy, and a street has been named after him. Since 2015 the town renamed Civic Holiday on the first Monday in August to Sir William H. Hearst Day.

9. Self-Improvement at the YMCA

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2012.4.5

c. 1907

Sault Ste. Marie's first YMCA opened in 1901 in this Queen Street building until moving to a new location on March Street in 1914. Nowadays YMCAs across the country operate as community centres, including swimming pools and fitness facilities, but Sault Ste. Marie's first YMCA was primarily a dormitory for unattached young men labouring in the nearby factories, and give them opportunities for reading and self-improvement.

Living conditions in most industrial cities in this period were hellish--the term 'dark satanic mills' was thrown around a lot.1 Organizations like the YMCA were founded to alleviate the suffering of the working classes. The establishment of a YMCA in Sault Ste. Marie represents the town's complete transition into a true industrial city, as well as reflecting the town's growing adoption of Victorian values of self-improvement through education and study.

* * *

The social reformer Sir George Williams was dismayed by the appalling urban conditions and thought the best way for the working classes to escape the drudgery of factory life was through education. He founded the YMCA as a bible study group for working men, giving them a safe space to improve their moral character.

By the late 19th century, the conditions in the 'satanic mills' had improved somewhat, and the YMCA adopted a more expansive philosophy, dedicating the organization to the "improvement of the spiritual, mental, social and physical condition of young men."2 By the time the YMCA opened in Sault Ste. Marie, it was a more multi-purpose men's organization for the town's growing population of industrial workers.

Unlike the Mechanics Institutes--libraries and lecture halls for the working classes--the YMCA offered not only opportunities for socializing, study, and education, but spaces for exercise and physical improvement. By the end of the 19th century, both institutions were central fixtures in most of Ontario's industrializing towns and cities, and were bastions of Victorian social mores that valued discipline, strong moral character, and intelligent discourse.

Society at large expected that men would take an active role in their own self-improvement, and avoid subjects and activities deemed frivolous. In 1863, Goderich, Ontario's Signal newspaper offered a piece of advice on gaining respectability in polite society, "Young men, spend the greater part of your pocket money in books, study to be intelligent, industrious and persevering in your calling... and... you will be useful and respected members of society."3

However, while it was expected of men to enjoy and commit themselves to intellectual pursuits, the same was not true for women. Women were not strictly forbidden from engaging in the same self-improvement within these associations, but it was widely understood institutions in the public sphere were intended for men. If women wanted to intellectually better themselves, they were expected to do so within their own sphere: the home.

10. Revolution in the Home

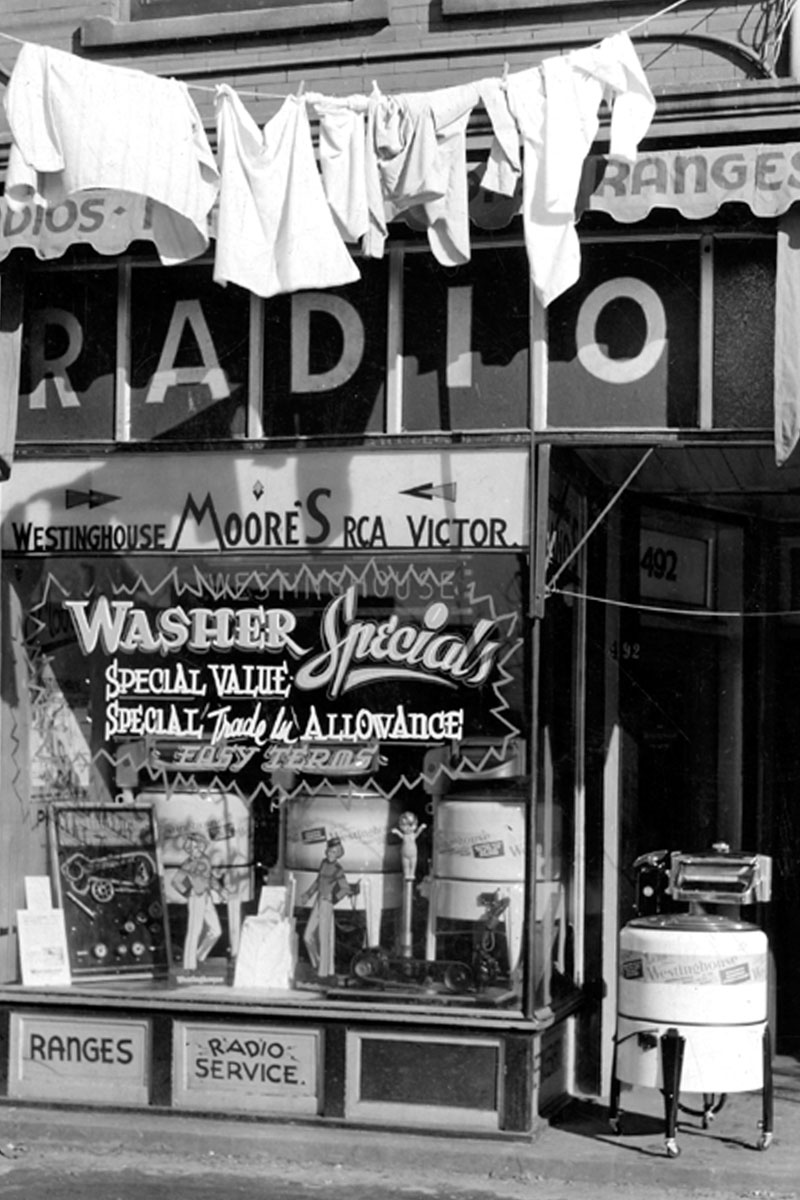

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 2004.18.1

c. 1930

The storefront of Moore's Appliance Store on Queen Street advertises all the latest household gadgets, like washing machines, electric stoves, and the new-fangled radio. Today every home we walk into is filled with a vast range of electric appliances (now most have computer chips in them). They were only possible with home electrification, a process that only really began in earnest after the First World War.

Electrification coincided with an era of seismic changes in women's role in society, as strict Victorian social mores expecting women to stay in the home gave way to greater female participation in the workplace, in society, and in government.

Electrification played more than a bit part in this revolution: Appliances like those sold by Moore's held out the possibility of liberating women from exhausting housework. As Eustella Burke wrote in a 1927 issue of Canadian Homes and Gardens, "Oh Wonderful Electricity! It has worked magic in the home. For her and her helpers, electricity replaces the physical labour with comparatively cheap mechanical energy."1

* * *

It was not long before people were getting their homes hooked up to power, and filling their homes with the appliances we all know and love today, drastically cutting down the time that women (primarily) spent on household chores, while freeing up time for other pursuits. Electric lighting also gave women many more productive hours in the day.1

By the 1920s, society's attitudes towards the role of women began to change drastically. Freed to some degree from the back-breaking monotony of housework, and through the tireless work of the suffragettes, and the devastating impact of the First World War, women began to take far more prominent roles in public life.

Where the Victorians believed in strict "seperate spheres" of influence, with women running the home, and men fulfilling a public, provider role, by 1922, white and black women had won the right to vote in Canada's elections. It was also becoming less stigmatized for women to hold jobs, and more common for women to pursue higher education. By 1929, some 20% of wage workers were women, although they were paid significantly less than their male counterparts. While women's rights and role in public society still had a long way to go, the 1920s was a decade of newfound freedom and the dawn of the modern woman.

However, long before women began to win the fight against a male-dominated society for rights and visibility, they worked within their sphere of influence to improve life for the women around them. In Sault Ste. Marie, one of the ways women worked for their community was through the act of creating a community cookbook. The cookbook lived for three editions, the third compiled by the St. Luke's Woman's Auxiliary in 1909, and titled the Culinary Landmarks, or Half-Hours with Sault Ste. Marie Housewives. The book's preface states that the book was not, "a haphazard collection gathered at random, but has been made from the choicest bits of the best experience of the members of St. Luke's Woman's Auxiliary and their friends, and we hope it may help many who have to travel the daily round of household duties."3 The book was created by women, in order to help other women in the home.

The cookbook, while helpful to women of the time, might seem strange to us today, with ingredient measures such as "butter the size of a walnut," or "flour enough to make a stiff batter."4 While community efforts such as the cookbook made daily life easier for women in the home, the movements of the 1910s and '20s changed women's lives drastically, bringing them firmly into the public sphere.

11. The Latest Fashions

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 997.12.1

1935

The Canadian Department Store Ltd. on Queen and March. As you can see the building survives today, and another two floors have been plopped on top. Department stores in those days were built with expansion in mind, meaning they were usually engineered so that more floors could be easily added. This is where Sault Ste. Marie's cosmopolitans came to sample the latest styles in American and European fashion.

While department stores such as Harrod's, La Bon Marche, Macy's flourished in England, France, and America respectively from the early 1800s, Canada didn't have its first true department store until Timothy Eaton opened his first store catering to Toronto's railway workers in 1883. Around this time, the Hudson's Bay Company made the somewhat surprising pivot from fur trade empire to department store powerhouse.

These stores were a modern marvel to Canadians, and met their increasingly sophisticated needs for the latest fashions. They were sprawling giants with cutting edge electrical lighting and built in the most fashionable shopping districts. By 1930, 14 out of every 100 dollars spent by Canadians went towards Eaton's, Simpson's and the HBC.1 The Canadian Department Store Ltd. was competing with some big names.

* * *

During Sault Ste. Marie's boom period from the 1890s to 1914, Victorian social ideals were the norm, and they were quite different from what any of us would be used to. Every aspect of personal expression and public behaviour for the middle and upper classes dictated strict social rules and expectations.

Sault Ste. Marie's Victorian culture was massively influenced by both Britain and America, who both developed these social codes along similar lines, but with some key differences. Where the British middle class viewed American democratic culture as vulgar and the American middle class as ambitious social climbers, the Americans took pride in their lack of snobbish aristocracy. The Canadian middle class was said to be a hybrid of the two: quiet and patient in their industrialization, but without the old world aristocracy.2

The people of Sault Ste. Marie learned derived these concepts for proper etiquette mostly from British and American journals, novels, and books. These sources suggested strict rules for everything from dress and grooming, to speech and appropriate reading material. For men, the emphasis was on understated, simple three piece suits in grey, black, or dark blue. The goal was to have a well-styled and tailored suit, without bold or attention seeking colours or jewelry.

Even hair style was a topic of heated debate and social pressure, as one man demonstrated in his letter published in the Goderich Signal in 1884, "When I, one of the old school, am told that because I will persist in parting my hair in the centre, I am guilty of dandyism, of dudism, and every other 'ism' that a respectable member of society should not be guilty of, I want to raise my goosequill aloft and place my protest on record. Gentle reader, I think I have said enough to conclusively prove that, although every man has the right to draw the line in hair parting where it suits... the proper place to do so is back from the centre of the forehead."3

Both men and women were expected to avoid all extreme expressions of emotion, and to maintain an exterior of self-control and propriety, and uncomfortable topics that could cause offense were strongly discouraged from proper conversation. Both sexes were also strongly urged towards self-improvement through reading and literature. While educational institutions and associations were public, male spaces, women still educated themselves from the private sphere of their homes.

The First World War shifted these attitudes drastically. Women who worked jobs traditionally held by men had a new taste of freedom outside the home--itself a scandalizing development for many men. The cumbersome and uncomfortable clothes women were expected to wear were impractical on the factory floor, and after the war women refused to return to the Victorian styles. Corsets and elaborate hairstyles were replaced by bobs and short, fringed dresses. Women started wearing flappers, the iconic dress of the 1920s which were straight and slim, and had a plunging neckline. In the public imagination, women who wore flappers smoked, drank in public, and even had sex out of wedlock--unthinkable just a decade before.

For men too, rules around fashion slackened somewhat. Weekends, a hard-won victory by the labour movement in the 1910s, left them with more leisure time. Relaxed leisurewear started to appear, such as flat caps, v-neck sweaters, and plus-fours (baggy pants cut off mid calf). Suits bloomed with bolder colours and patterns, and slim, jazz style cuts.4

These changes are a major part of what is popularly remembered as the Roaring '20s. In places like Sault Ste. Marie, this period of relaxed social rules and comparatively free behaviour didn't last long. The Stock Market Crash of 1929, and the Great Depression that followed, meant that most people's interest in fashion was quickly replaced with an interest in survival.

12. The Cenotaph

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.16.47a

1924

This is the dedication of Sault Ste. Marie's cenotaph, a somber occasion given the titanic scale of the city's sacrifice in the War to End All Wars.

When the First World War erupted in August 1914, the people of Sault took up the fight with vigor. The first contingent from the local militia marched down Queen Street on August 20 and embarked on trains with the ultimate destination of Flanders Fields. They were but the first of thousands to make the journey. Many would not return.

It is a beautiful, moving monument, topped with bronze sculptures. The crouching male figure represents War, under a "'Shield of Right' represented by a draped female holding a sword and a sprig of maple leaves. Side panels depict men reluctantly answering the call to arms and soldiers helping the wounded."1

If you go read the inscribed names on the monument you can't help but be shocked by the immense scale of the tragedy: there are 350 names of men from Sault Ste. Marie who fell in that war, a devastating blow to a young city of Sault's size.

* * *

From little towns, in a far land, we came, To save our honour and a world aflame; By little towns, in a far land, we sleep, And trust those things we won To you to keep. It was written by Rudyard Kipling specifically for Sault Ste. Marie after an eloquent request from a local. Before World War I Kipling was one of the chief promoters of British imperialism, and a generation of young men were raised on his exhortations to honourable and manly conduct and the building of empire. He espoused the racist paternalistic ideology of colonialism that was widespread at the time, which can best be summarized by the phrase he coined: 'white man's burden'. When the war began he was one of its biggest boosters, and wrote many poems glorifying British heroism, while shaming those who didn't enlist.

His 18-year-old son John attempted to enlist but was rejected multiple times on medical grounds. Rudyard, however, was able to pull strings and get John accepted into the Irish Guards. John was killed in 1915. The death shocked Kipling, and he later wrote "If any question why we died / Tell them, because our fathers lied."2

Men from Sault Ste. Marie took part in every major battle of the Canadian Expeditionary Force between 1915 and 1918. When they returned home after the war many felt the same way as Kipling's words: they were disillusioned by the gross incompetence and monstrous indifference of many generals that had let so many die in battles that were at once among the most horrific and futile in all military history.

One of the most widely reviled generals after the war became Sir Douglas Haig, commander of all British and Canadian forces in France. His insistence on continuing the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, long after there was any military value in it, cost tens of thousands of lives. The historian Alan Clark wrote that most British generals were "grossly incompetent for the tasks which they had to discharge and that Haig, in particular, was an unhappy combination of ambition, obstinacy and megalomania."3

Haig attended the unveiling of the cenotaph. He is the man on the right shaking hands.

13. The Italian Experience

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X982.31.1

1941

A company of Sault Ste. Marie soldiers pose for a photograph in front of the courthouse. They're about to depart to fight with the 5th Canadian Armoured Division in Italy during the Second World War.

Sault Ste. Marie had been a hugely popular destination for Italian immigrants to Canada in the early 20th Century, and in 1914 a quarter of the city's population were of Italian extraction. Most of them settled in Little Italy in Steelton, just up the road from here.

The Victorian notions of racism, widespread among Canadians of British extraction, also held that Italians were racially inferior. Therefore Sault's Italians faced racial discrimination like many other minorities.

Politics in Italy also became a major issue as well. Not so much in the First World War, when Italy was fighting alongside the Allies, but during the Second World War, when Fascist Italy was an enemy of Canada. A major fraternal organization called the Order of the Sons of Italy, established a lodge in Sault in 1915 and held wide influence across Sault's Little Italy. When Mussolini's fascists seized control of Italy in 1922, many members of the Order were sympathetic to fascism, and an intense and public battle between fascists and leftists for ideological control over the organization was waged between 1924 and 1946.1

Many men from Sault served in the Italian Campaign from 1943-45, but few of them were Italian-Canadians. For much of the war many Italian-Canadians were interned as enemy aliens, and their loyalty treated with suspicion. There is a plaque on the Memorial Tower that we will pass in a later stop, honouring the sacrifices of those Italian-Canadians who fought and died for Canada in both world wars and Afghanistan.

* * *

According to an Italian government report, by 1914 some 3,000 of Sault Ste. Marie's 12,000 residents were Italian immigrants. While some of these opened shops and businesses, many worked as both skilled and unskilled labourers at the Algoma Steel Mill.

For these heavy industry labourers, the days were long, and the pay abysmally low by the standards of the day. In 1914, the average common labourer worked ten hour shifts for 17.5 cents an hour. The report states that while the Italians were "treated well," the work was backbreaking and dangerous and medical insurance claims for injury were frequent.2

In addition to the tough labour conditions, the Italian community in Sault Ste. Marie faced prejudice from some of the city's white protestants. A chapter of the Klu Klux Klan was established in Sault, an organization more usually associated with the white supremacy of the segregated American South than northern Ontario.

The majority of Sault's KKK activities involved burning crosses to intimidate the city's Catholics, and the overwhelmingly Catholic Italians were right in their crosshairs. Local Dorothy Bonell reported in her oral history that the city's Italians feared the KKK more than the Italian Mafia. She remembers a day from her childhood when she attended a family gathering, and was ordered to shutter the windows, turn off the lights, and quiet down when a KKK procession was spotted marching up the street.3

This chapter of the KKK boasted more than 600 members by the mid 1920s, but suddenly disbanded in 1929 at the beginning of the Depression. According to the chapter's former secretary years later, "Running around in hooded costumes had to take a second place to trying to feed, clothe and shelter families in the Depression."4

Even though the KKK ceased activities, the racist sentiments of many of Sault's white protestants simmered barely beneath the surface.

These feelings only heightened during World War II, when Italian-Canadians were deemed enemy aliens by the federal government after Italy's declaration of war on Britain and France in 1940. Many Italian families across Ontario were subjected to prejudice and discrimination and had their civil liberties suspended, while others lost their jobs. Many were even interned in Camp Petawawa in Northern Ontario on suspicion of being enemy agents.

The end of the war and a shortage of labourers once again opened Canada's doors to Italian immigration, and following the war, the surge of Italian immigration was so great that in 1958, Italy surpassed Britain as the country's primary source of new immigrants.5 Now, vibrant "Little Italys" can be found in many Canadian cities, with the greatest concentrations in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

14. Rise of the Automobile

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X981.2.2

1916

A car barrels through the rising waters of the Saint Mary's River during one of Sault Ste. Marie's occasional floods.

While the city's location on the banks of the river was key to the town's success, first in the fur trade, and later as an industrial centre, it was not without risk. As numerous tributaries, streams, and creeks swelled every year with snowmelt, or in sudden rain storms, the banks of the St. Mary's River even now sometimes fail to contain the rising waters--with potentially catastrophic consequences.

As we can see from this Ford Model T ploughing determinedly through the floodwater, even early cars were quite capable of negotiating challenging conditions. Nevertheless, these cars lacked good suspensions, and most roads at the time were unpaved, making a drive teeth-chatteringly uncomfortable proposition. The increasing number of car owners (who also happened to be quite rich and influential) demanded fully paved roads--not the mere cobblestone or gravel roads common at the time. So in the 1910s the project of paving Canada's roads became a major national undertaking.

* * *

Today we take it for granted that we can hop in a car and drive to the other end of the country along the smooth, well-maintained Trans-Canada Highway. But before the highway was built the appalling quality of roads made a trans-Canada drive an almost preposterously difficult challenge.

Consider the experience of the first people to actually accomplish the Trans-Canada drive: Thomas Wilby, an English author, and Jack Haney, his driver and mechanic. Wilby was convinced the automobile would inevitably rise to supremacy and render the railways obsolete. He admitted that in 1912 "on the Canadian road, the car is not yet a welcome dictator." Take a look around Canada today however, and you'll see it's a 'welcome dictator' today.1

Wilby and Haney departed Halifax on August 27, 1912, in a Canadian-designed and built Reo Motor Car. At the time the entire country had only about 16 kilometers of paved road. The roads between cities were so primitive as to be nonexistent.

They suffered dozens of breakdowns, scores of flat tires, and hundreds of times stuck in the mud. The 1,500 km stretch between Sault Ste. and Winnipeg proved entirely impossible. There were no passable roads at all. Instead they loaded their Reo on a ferry across Lake Superior. They arrived in Victoria two months later, haggard, and thoroughly sick of each of each other's company (Wilby wrote a book about the adventure called A Motor Tour Through Canada, and never mentioned his driver Haney by name), but otherwise triumphant in their journey.

Thanks to labour relief projects during the Great Depression, workers successfully completed a paved road between Sault Ste. Marie and the Quebec border, effectively connecting the town to Ontario's urban core. As Wilby had predicted years earlier, the highway opened Sault Ste. Marie in a way the railroad had never quite achieved. Following the completion of the Trans Canada Highway north to Wawa, and the International Bridge across St. Mary's River to Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, the town became a central transportation hub in the Great Lakes Region.

15. A Rich Tapestry

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X2006.4.31b

c. 1950

In this photo, an excited crowd gathers outside for entrance into the newly opened Sault Memorial Gardens. Despite its name, the large building was not a conservatory, but rather an arena for Canada's fondest winter pastime -- ice hockey.

When the arena was originally built it also served as a memorial in the wake of World War II. The tower, the only part of the original structure that remains, contains a list commemorating Sault Ste. Marie's Italian-Canadian soldiers who fell in battle. The new arena, named GFL Memorial Gardens hosts the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds of the Ontario Hockey League. It was during his time with the Greyhounds that history's greatest hockey legend Wayne Gretzky first wore the number 99 on his jersey.

* * *

Now, the influence of several groups can be felt in Sault Ste. Marie. From the Italian community which now comprises approximately a fifth of the population, just behind those who claim Irish, English, and French heritage. These, and the city's Saulteaux and Metis communities, and those of numerous other visible minorities, make up the rich tapestry of people who chose to make this spot home. Over a century later, the prediction of one travel writer that the beauty and spirit of Sault Ste. Marie would draw visitors and new residents from all over the world has borne out.

Endnotes

1. The Fur Trade Era

1. "Ermatinger House National Historic Site of Canada," Canada's Historic Places, online.

2. Osborne & Swainson, The Sault Ste. Marie Canal, (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986), 8.

3. Myron Momryk, “ERMATINGER, CHARLES OAKES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003, online.

4. Edward H. Capp, The story of Baw-a-ting; being the annals of Sault Ste. Marie (Sault Ste. Marie: Sault Star Presses, 1904), 153.

5. "Ermatinger House National Historic Site of Canada", online.

6. Myron Momryk, “ERMATINGER, CHARLES OAKES,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), online.

2. Life in a Trading Post

1. Capp, 197.

2. Capp, 178.

3. The Tides of Change

1. Whitefish Island Dispossession

2. Osborne & Swainson 22.

3. Osborne & Swainson 22.

4. Osborne & Swainson 23.

5. Capp, 172.

4. The Catholic Legacy

1. Osborne & Swainson 22.

2."History of the Precious Blood Cathedral Part III," Precious Blood Cathedral, of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie, 10, PDF, online.

5. Entering the Modern Age

1. "Canada's Carnegie Libraries," Canada's Historic Places, online.

2. "Remember This? The time Andrew Carnegie built two libraries for the Sault," Soo Today, 27 Dec. 2015, online.

3. "Census Profile: Sault Ste. Marie," Statistics Canada, online.

4. Momryk, “ERMATINGER, CHARLES OAKES,” online.

6. Supercharging a City

1. Duncan McDowall, "Clergue, Francis Hector." Dictionary of Canadian Biography, online.

2. McDowall, online.

3. "The Industrialization Process" Sault Ste. Marie: A Community through the Prism of it's Heritage Sites, online.

4. McDowall, online.

7. Conquering Public Health

1. "Remember This? Before the PUC," SooToday.com, Aug. 27, 2017, online.

2. Elizabeth Iles, As the Grey Sisters: Sault Ste. Marie and the General Hospital, 1898 - 1998, (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998), 20.

3. "Remember This? Before the PUC," online.

8. The Premier from the Sault

1. "About Hearst," City of Sault Ste. Marie Website, online.

9. Self-Improvement at the YMCA

1. "Notes & Queries: What were William Blake's dark satanic mills?", The Guardian, 12 Sept. 2012, online.

2. "Our History, A Brief History of the YMCA Movement," Marshfield YMCA Website, online.

3. Andrew C. Holman, "'Cultivation' and the Middle-Class Self: Manners and Morals in Victorian Ontario," in Ontario Since Confederation: A Reader, ed. Edgar-Andre M. & Lori C. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000) 114.

10. Revolution in the Home

1. Dorotea Gucciardo, "The Powered Generation: Canadians, Electricity, and Everyday Life," (2011), Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository, 134.

2."Electric Range - 1892," National Maglab. Dec. 10, 2014, online.

3."Remember This? The Housewives of Sault Ste. Marie, and their famous cookbook," Sootoday.com. April 30, 2017, online.

4. "Remember This? The Housewives of Sault Ste. Marie, and their famous cookbook," online.

11. The Latest Fashions

1. Joe Castaldo, "The death of the department store (1796 - 2017)," Macleans, 29 Nov. 2017, online.

2. Holman, 108.

3. Holman, 111.

4. Karina Reddy, "1920 - 1929," Fashion History Timeline, Aug. 11, 2019, online.

12. The Cenotaph

1. "Sault Ste. Marie Cenotaph," Canada's Historic Places, online.

2. Amanda Ameen, "The Truth Behind a Poem," The Contemporary Poem, 22 Oct. 2016, online.

3. Laura Walker, "Haig and British Generalship during the war," The British Library, 29 January 2014, online.

13. The Italian Experience

1. Angelo Principe, “The Fascist-Anti-Fascist Struggle in the Order Sons of Italy of Ontario, 1915-1946”, Ontario History, 106, (1), 3.

2. Gerolamo Moroni, "The Italian Colony at Sault Ste. Marie" Upper County: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region, 11.

3. "Remember This? The Sault's history of cross burnings and fear," Sootoday.com. 26 June 2016, online.

4. "Remember This? The Sault's history of cross burnings and fear," online.

5. Franc Sturino, "Italian Canadians," The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 23, 2019, online.

14. Rise of the Automobile

1. Alan Macearchen, "Goin' down the road: the story of the first cross-Canada car trip," The Globe and Mail, April 30, 2018, online.

Bibliography

"About Hearst," City of Sault Ste. Marie Website. https://saultstemarie.ca/City-Hall/City-Departments/Community-Development-Enterprise-Services/Community-Services/Recreation-and-Culture/Historic-Sites-and-Heritage/Municipal-Heritage-Committee/Sir-William-H-Hearst/About-Hearst.aspx

Ameen, Amanda. "The Truth Behind a Poem." The Contemporary Poem. 22 Oct. 2016.

"Canada's Carnegie Libraries," Canada's Historic Places.

Capp, Edward H. The story of Baw-a-ting; being the annals of Sault Ste. Marie. Sault Ste. Marie: Sault Star Presses, 1904.

Castaldo, Joe. "The death of the department store (1796 - 2017)," Macleans. 29 Nov. 2017. https://www.macleans.ca/economy/business/the-death-of-the-department-store-1796-2017/

"Census Profile: Sault Ste. Marie," Statistics Canada, online.

"Ermatinger House National Historic Site of Canada," Canada's Historic Places.

Gucciardo, Dorotea. "The Powered Generation: Canadians, Electricity, and Everyday Life," (2011), Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository.

"History of the Precious Blood Cathedral Part III," Precious Blood Cathedral, of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie, 10. PDF. https://d2y1pz2y630308.cloudfront.net/2643/documents/Precious%20Blood%20History%20Part%20lll1.pdf

Holman, Andrew C. "'Cultivation' and the Middle-Class Self: Manners and Morals in Victorian Ontario," in Ontario Since Confederation: A Reader, ed. Edgar-Andre M. & Lori C. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Iles, Elizabeth. As the Grey Sisters: Sault Ste. Marie and the General Hospital, 1898 - 1998. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1998.

Macearchen, Alan. "Goin' down the road: the story of the first cross-Canada car trip." The Globe and Mail. April 30, 2018. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/goin-down-the-road-the-story-of-the-first-cross-canada-car-trip/article4487425/

McDowall, Duncan. "Clergue, Francis Hector." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/clergue_francis_hector_16E.html

Momryk, Myron. “ERMATINGER, CHARLES OAKES,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/ermatinger_charles_oakes_6E.html

Moroni, Gerolamo. "The Italian Colony at Sault Ste. Marie." Upper County: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region.

"Notes & Queries: What were William Blake's dark satanic mills?" The Guardian, 12 Sept. 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/sep/12/william-blakes-dark-satanic-mills

Osborne & Swainson. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986.

"Our History, A Brief History of the YMCA Movement," Marshfield YMCA Website, http://www.mfldymca.org/about_us/history_national.php

Principe, Angelo “The Fascist-Anti-Fascist Struggle in the Order Sons of Italy of Ontario, 1915-1946”. Ontario History, 106, (1), 1-33.

Reddy, Karina. "1920 - 1929." Fashion History Timeline. Aug. 11, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1920-1929/

"Remember This? Before the PUC," SooToday.com, Aug. 27, 2017. https://www.sootoday.com/columns/remember-this/remember-this-before-the-puc-704103

"Sault Ste. Marie Cenotaph." Canada's Historic Places.

"Remember This? The Sault's history of cross burnings and fear," Sootoday.com. June 26, 2016. https://www.sootoday.com/columns/remember-this/remember-this-the-saults-history-of-cross-burnings-and-fear-325258

"Remember This? The time Andrew Carnegie built two libraries for the Sault," Soo Today, 27 Dec. 2015,

Sturino, Franc. "Italian Canadians." The Canadian Encyclopedia. May 23, 2019. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/italian-canadians

"The Industrialization Process." Sault Ste. Marie: A Community through the Prism of it's Heritage Sites. http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/205/301/ic/cdc/ssm/text_only/english/frameset.html

Walker, Laura. "Haig and British Generalship during the war." The British Library. 29 January 2014.