Walking Tour

The Sault Rapids

Engine of Sault Ste. Marie

Taylor Peacock

Sault Ste Marie's history has always revolved around the rapids. The story of industry, life, and labour in this city begins with the whitefish, moves on to the fur trading empires, the industrial giant created by Francis Clergue, and the canals that are the lifeblood of commerce on the Great Lakes today. The story follows the struggles of the working classes as he builds the canal, and later, adapts to industrial mechanization. It ends with the modern day output of steel, and the end of the twelve hour day.

Follow along as we take you through the history of life and labour in Sault Ste Marie, using old photographs and paintings to see the Sault through the eyes of people who came before.

The tour begins along the hub trail, as you walk towards the canal. Walking down the waterfront, the tour uses critical spots in William Armstrong paintings of idyllic scenes, such as the portage, to understand how Sault Ste Marie fit into the fur trade. From there we turn right on Canal Drive, and left on Huron Street, where a u-shaped stroll on both sides delve into the rise of industrialization and capitalism of Francis Clergue using photos of the Lake Superior Company building and the 1903 riot.

As you walk back towards Canal Drive, taking a right towards the canal a photo of the Old Paper company tells the tale of the fall of the Clergue Empire. We follow Canal Drive back towards the Hub Trail, stopping just on the bridge to examine the history of the Red River Rebellion at the Wolseley Camp.

Continuing down Canal Drive, the scenic route when you reach the National Historic Site depicts the history of the Sault Ste Marie Canal. Beginning in 1889, the tour walks you into the history of the canal. Walking past the National Historic Site, you encounter the locks opening in 1895, and the accident of 1909, as well as the troubled and tumultuous life of canal workers in Canadian history. Turning back to the National Historic Site, the tour ends on the lawn, where you can stand in the footsteps of Sault Ste Marie's soldiers as they departed for the Western Front in 1914.

This project is a partnership with the Sault Ste. Marie Downtown Association, the Sault Ste. Marie Museum, and Tourism Sault Ste. Marie.

1. An Ancient Gathering Place

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X980.89.1

c. 1860s

This painting captures a peaceful moment on the banks of the St. Mary's River. The artist was William Armstrong, an influential painter in 19th Century Canada, who depicted this scene while he passed through Sault Ste. Marie with the Wolseley Expedition en route to Louis Riel's Red River Rebellion.

The tranquility of the scene contrasts with the bustling harbour of the two Sault Ste. Maries we see today. Yet this place has been an important gathering place for centuries, drawing First Nations peoples from far and wide to fish from the bountiful rapids--Baawitigong, as it was known in Ojibwe

* * *

For centuries--perhaps even millennia--bands of First Nations people would travel here in the summer, from as far away as Hudson's Bay in the north and the Mississippi to the south. They came to fish and trade furs, corn, tobacco, maple syrup and copper. The banks of the river and the surrounding forests provided ample hunting opportunities, making life here rich and plentiful.

The different peoples who gathered here engaged in politics and religious rituals as well, which is why the Ojibwe also called it the 'Gathering Place of the Three Fires Confederacy.'2

Many bands stayed for the whitefish spawning season in the fall, a staple of the Saulteaux people who resided here permanently. They also fished pike, lake trout, sturgeon, and pickerel. At that time of year the beach here would be a lively scene as fishermen and women exhibited great skill in negotiating the rapids in their birchbark canoes to catch thousands of whitefish.

Writing in the 1880s, Anna Jameson describes the breathtaking fishing techniques of the local Saulteaux, skills that had been handed down from generation to generation:

"I was watching with a mixture of admiration and terror several little canoes which were fishing in the midst of the boiling surge, dancing popping about like corks. The canoe used for fishing is very small and light; one man (or woman more commonly) sits in the stern, and steers with a paddle; the fisher places himself upright on the prow, balancing a long pole with both hands, at the end of which is a scoop net. This he every minute dips into the water, bringing up at each dip a fish, and sometimes two... The manner in which they keep their position upon a footing of a few inches, is to me as incomprehensible as the beauty of their forms and attitudes, swayed by every movement and tuen of their dancing barks is admirable."3

2. The Age of the Canoe

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.29.21

c. 1860s

This is another William Armstrong painting showing one of the key locations along the banks of the St. Mary's River: the beginning of the portage trail. The rapids were not navigable by boat, and initially those seeking to get across would beach their canoes and carry them and their supplies--portage them--along this trail to the Lake Superior side.

In 1797 the North West Company built an 800 metre mini canal for these fur trading canoes, complete with locks. It was the first canal through the Sault rapids. In 1896 Francis Clergue would restore part of the canoe canal as a heritage site, which still survives today, which we will visit a little later in this tour.

Canoes were the dominant mode of transportation in this region until the very recent past, and it was their utility by the First Nations, and later the fur traders, voyageurs as they were known, that have made them an enduring symbol of Canadian identity.

* * *

Fur trade expeditions would last months at a time, and the hardy traders were expected to not only fit all the supplies they needed to survive, but huge quantities of trade goods and heavy bales of fur. It's no surprise then that every square inch of the canoe's space was carefully accounted for.

One fur trader's cargo manifest from 1800 lists all the supplies crammed into a 20 foot canoe running from the Northwest to the Red River: "general trade merchandise, 5 bales; tobacco, 1 bale and 2 rolls; kettles, 1 bale or basket; guns, 1 case; hardware, 1 case; lead shot, 2 bags; flour, 1 bag; sugar, 1 keg; gunpowder, 2 kegs; wine, 10 kegs." The bales each weighed 90-100 pounds, and kegs were 9 gallons. The canoe would have had equal amounts of provisions, and space would have been tight.2

Hauling all these supplies across the Canadian wilderness was incredibly arduous and dangerous. Why would these voyageurs sign up to this life, and what kind of people were they?

Most Europeans living in Canada in the 18th and early 19th Centuries were independent farmers or worked at home in cottage industries. The voyageurs on the other hand worked under contract for the large fur trading companies, the North West Company or the Hudson's Bay Company. These were some of Canada’s earliest 'jobs' in the modern sense. For the most part, farming and cottage industries allowed families to survive at little more than a subsistence level, but the fur trade offered lucrative and regular employment. 3

Important to the history of Sault Ste Marie was the North West Company’s less regulated way of life. Compared to the stringent rules and regulations governing the behaviour of HBC traders, the North West Company had a laissez faire attitude towards its voyageurs. At a post like the one here at Sault Ste Marie, they could spend freely on gambling and drinking, which was associated with the masculine ideal of the conquest of nature.

The life of the voyageur is remembered romantically, idealizing the freedom to make a fortune traversing the wilderness and braving dangers, but much of what we know of their lifestyle comes from spotty records. Primary accounts are rare, as most of these men were illiterate. Instead what we know of the lives of the fur traders comes from the clerks and the bosses that paid them.

Daniel Hormon, a North West Company clerk, wrote about fur traders in 1813: "ficle & changable as the wind, and of a gay and lively disposition...they make Gods of their bellies, yet when the necessity obliges them..they will endure all the fatigue and misery of hard labour & cold weather for several Days following without much complaining."4

For a man on the job, a day would consist of 16-18 hours at paddle, or if portaging, carrying canoes and supplies from one river to the next. They'd likely burn 4000-5000 calories in a day, making the food they carried their most important resource.5

3. The Fur Trade Post

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.29.25

1889

This painting of the old fur trade post near the end of its life shows several of the buildings that once stood on this site. Notice the powder magazine at the left, which is today the Clergue Blockhouse located at the Ermatinger Clergue National Historic Site, which is the start of our Queen Street tour.

The North West Company established this trade post in the 1790s, and a quick glance at a map can tell you why: it dominated the Saint Mary's River that connected Lake Huron to Lake Superior. The post was destroyed by the Americans during the War of 1812, but quickly rebuilt. In 1821 the North West Company was taken over by the Hudson's Bay Company, and this post became an HBC operation until the end of the fur trade in the 1860s.

* * *

On the first leg of the journey traders from the North West Company, and later the Hudson's Bay Company, paddled huge 12-man canoes from Montreal and through lakes Ontario, Erie, and Huron before arriving at Sault Ste. Marie. Here they'd take on provisions before continuing onwards into Lake Superior, usually winding up at Fort William, where Thunder Bay is today.

There they'd hand over their trade goods to the interior fur traders, and take on bales of furs before turning around and beginning the long journey back to Montreal. As long and gruelling as this journey was, it was considered the easy job. The men who made the next leg of the journey faced the real challenge. Paddling upriver from Fort William in smaller canoes, most undertook a 1,000 km journey to Lake Winnipeg, through rapids, many difficult portages, and frequently inhospitable weather conditions.

There was very little food to be found between Lakes Superior and Winnipeg, and the voyageurs often sought the aid of Indigenous peoples they encountered along the way. Nevertheless, the threat of starvation was never far. To reflect the heightened dangers they faced the interior traders were paid more than those who paddled across the great lakes, who they derisively called mangeurs de lard or “pork eaters” for the comparatively rich diet of sea biscuit, salt pork and beans they enjoyed.3 4

4. End of an Era

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.24.66

c. 1900s

The fur trade was the lynchpin of early Sault Ste Marie's economy, and its decline over the course of the mid-19th Century caused the community to stagnate. In the 1860s the trading post was shut down and the site fell into disrepair.

Geography and global economic trends dictated the decline of the fur trade and the shuttering of the trade post at Sault Ste. Marie. It would not be long however before those same forces brought the Industrial Revolution to Sault Ste. Marie, giving the community a new future.

It was brought here by the industrialist Francis Clergue, who established a pulp mill, whose headquarters we can see here.

* * *

Beavers take a notoriously long time to breed, and it only took a few years of continuous exploitation to cause their numbers in any given area to collapse, which in turn forced the voyageurs to range further and further afield in search of furs. The NWC's Great Lakes route was longer, more challenging, and less profitable, since furs had to be carried so much further in smaller canoes, whereas the HBC could fill the holds of large vessels with furs at York Factory. Furthermore, when the United States extended its territory over the southern Great Lakes, they evicted NWC traders favour of their own trading companies. American competition became so fierce that Americans used the War of 1812 as an excuse to mount an expedition to Sault Ste. Marie and burn down the post.

Squeezed between these encroaching forces from both the north and the south, the North West Company sank into irrelevance. In 1821 it was finally absorbed by the HBC. Then the HBC took over operations at Sault Ste. Marie and the rest of the Canadian portion of the Great Lakes, they didn't shut down the network, but they didn't invest in it much either. Sault Ste. Marie became a quiet backwater, and by the 1850s the fur trade itself had more or less ceased. By 1869 the HBC finally shut down the post, bringing an end to this chapter of Sault Ste. Marie's history.1

One important industry persisted during this period alongside the fur trade: fishing. In the early part of the 1800s, like the Indigenous peoples before, fur trading corporations capitalized on the whitefish of the Sault Ste Marie rapids. Until the 1850s, fishing and canning was a significant industry at Lake Superior, and in particular Sault Ste Marie. So much so that we have a record of the Hudson's Bay Company complaining of the American Fur Trade Companies set up on Whitefish Island in 1824.2 However, overfishing and improper planning would however lead to its collapse in the mid 1850s.

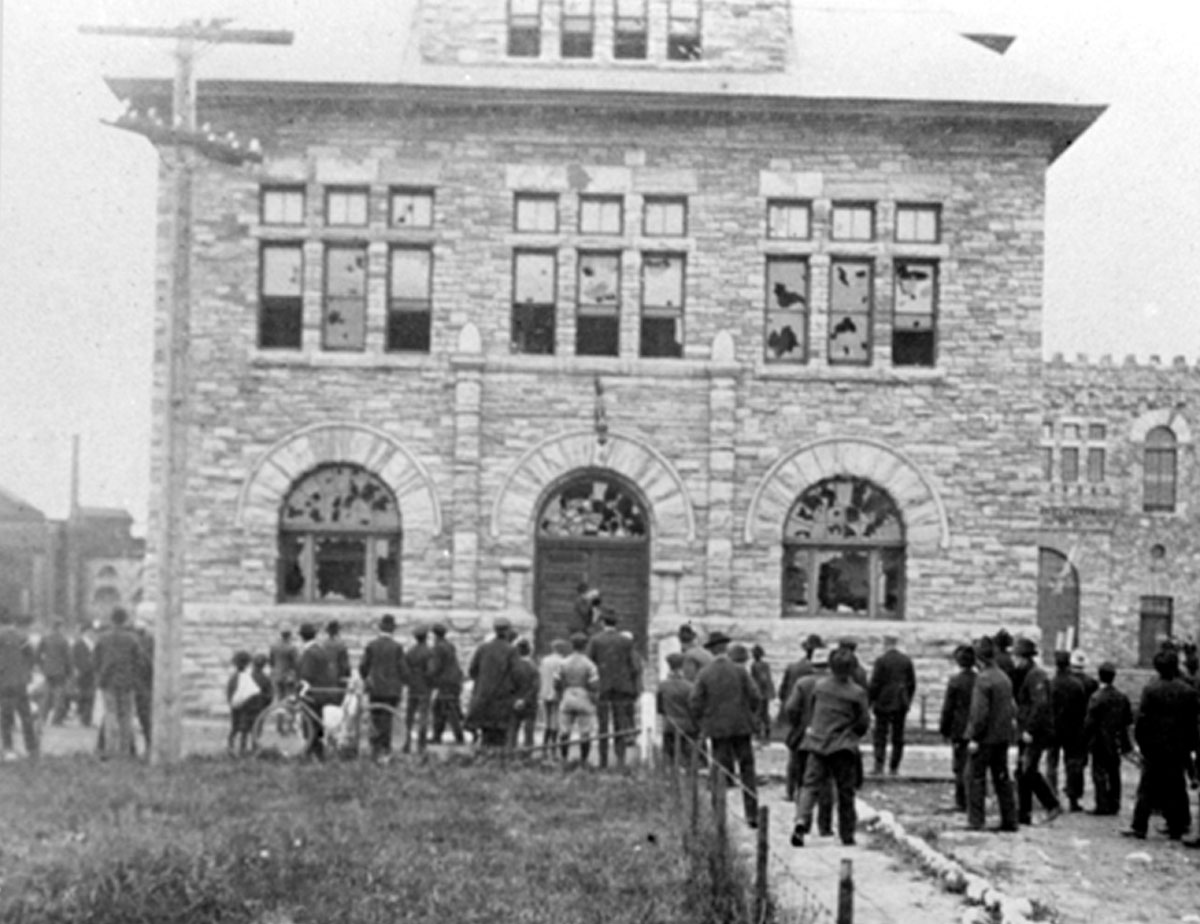

5. The Riot of 1903

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X983.12.1c

1903

The above photo shows the riot in the Clergue Empire in 1903, a key part of Sault Ste Marie history. When Francis Clergue arrived in Sault Ste Marie, he saw an unlimited potential for industry.

* * *

He was described as a ''captain of industry' of the Veblen mould, 'a man of workman-like force and creative insight into the community's needs, who stood out on a footing of self-help, took large chances for large ideals."5

When visited by the Premier in 1902, Clergue would boast he had 7000 workers under his stead, and a payroll of 170,000. His workers would make up the vast majority of Sault Ste Marie’s population. What occurred during the late 1800s was the increase in industry in Canada that was very reliant on a cheap labour force, alongside the allowance and support of private ventures by the Canadian government. The labour force that Clergue would come to employ would have been made up of immigrants, already seasoned to industrial labour, that would have been wholly reliant on the income that such work provided. However, as depicted in the image above, by 1903 Francis Clergue's tenure in Sault Ste. Marie was bound for troubled waters.

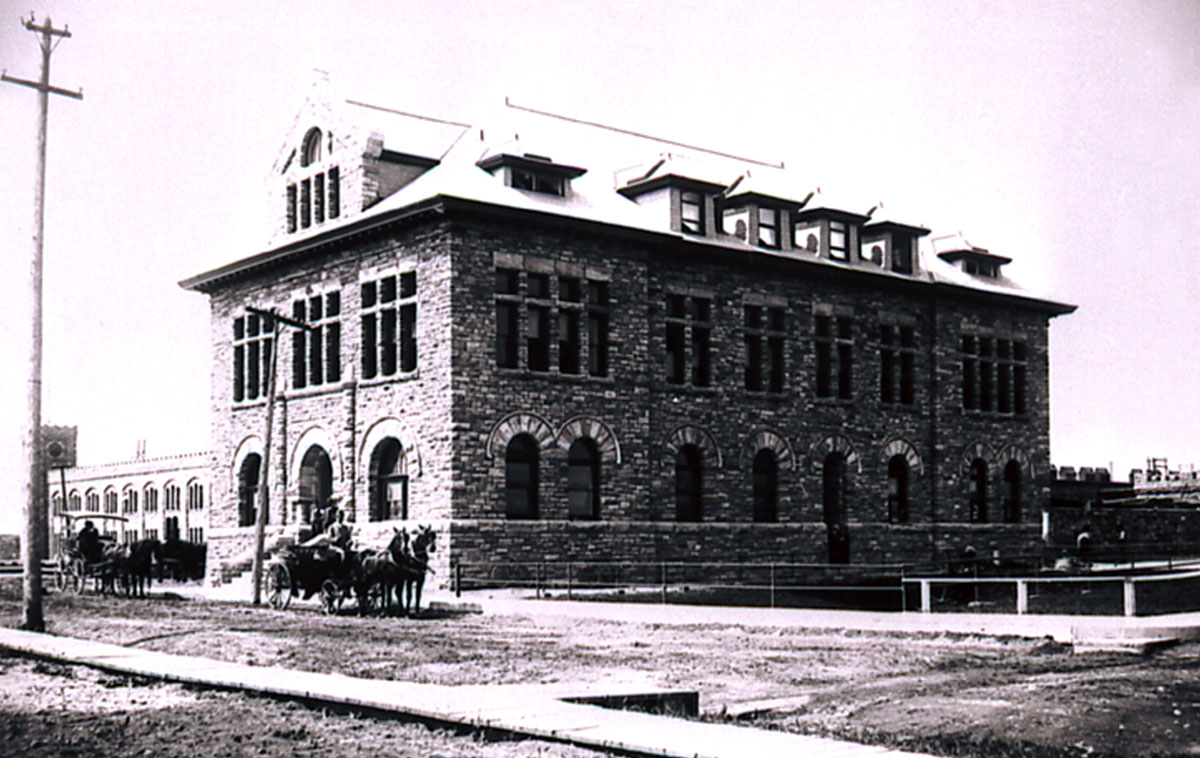

6. An Empire Crumbles

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X988.20.1

1903

Taken in 1903, the above photo shows the men sent from Toronto to guard the Paper Company building against rioters even though the riot had ended the day before.

* * *

The events of September 27th were the culmination of two key problems that Francis Clergue had failed to address in the early years of his industries. First, and most critically, all of the businesses were unstably intertwined and relied not only on government subsidies of around a million then, closer to 22.5 million today. in the case of Algoma Steel, but also external loans from a New York Company to make the payroll.2 Secondly, and even more critically was the niche nature of Clergue's steel production. Clergue built Algoma Steel in 1901 to accompany and make use of the ore in Michipicoten, just North of the Sault. To capitalize on the iron ore nearby, Clergue opened and funded the Helen mine and erected Bessemer furnaces to turn the iron ore into steel railways.

Yet, Algoma Steel failed to thrive in part because construction on the factories were not complete fully until 1904. While the first steel rails were produced in the Bessemer furnace in 1902, the iron ore had to be processed elsewhere and expensively shipped to Algoma Steel. Further, Clergue had made the critical error of assuming that the demand for railways would last long enough to allow for the company to diversify its interests. By the time that Clergue's company had started producing rails the market was exceptionally competitive with numerous American contenders who were selling below the market price, and he had to rely on government protections such as tariffs to ensure his sales.

In 1903, Prime Minister Laurier, after having been pressured not just by Clergue but other supporters of the tariffs was caught saying: J'ai dit dix fois a Clergue,' he grumbled in early 1903, 'que j'etais pret, pour ma part, a imposer des droits sur les rails d'acier du moment que nous pourrions en fabriquer au Canada, et Clergue n'est pas encore en etat de le faire." When translated to English, the comment is "I said to Clergue ten times, 'he grumbled in early 1903,' that I, for my part, was ready to impose duties on steel rails as long as we could make them in Canada, and Clergue is not yet ready to do so." 3

Between 1900 and 1903, the Canadian government struggled to balance the desires of Clergue and the Algoma Steel Corporation with those who needed steel. In 1903, they imposed a seven dollar per ton tariff on imported rails which protected Algoma Steel and similar Canadian businesses, but caused strife for companies that relied on the imported American steel.4 In 1900, Clergue and Algoma Steel had been granted a 150,000 ton contract with the International Railway but by its closure in 1903, had failed to deliver. When the Lake Superior Company faced men angered at their lack of pay in 1903, for all of his charisma and charm, Clergue had effectively dug himself and his Empire into a hole.

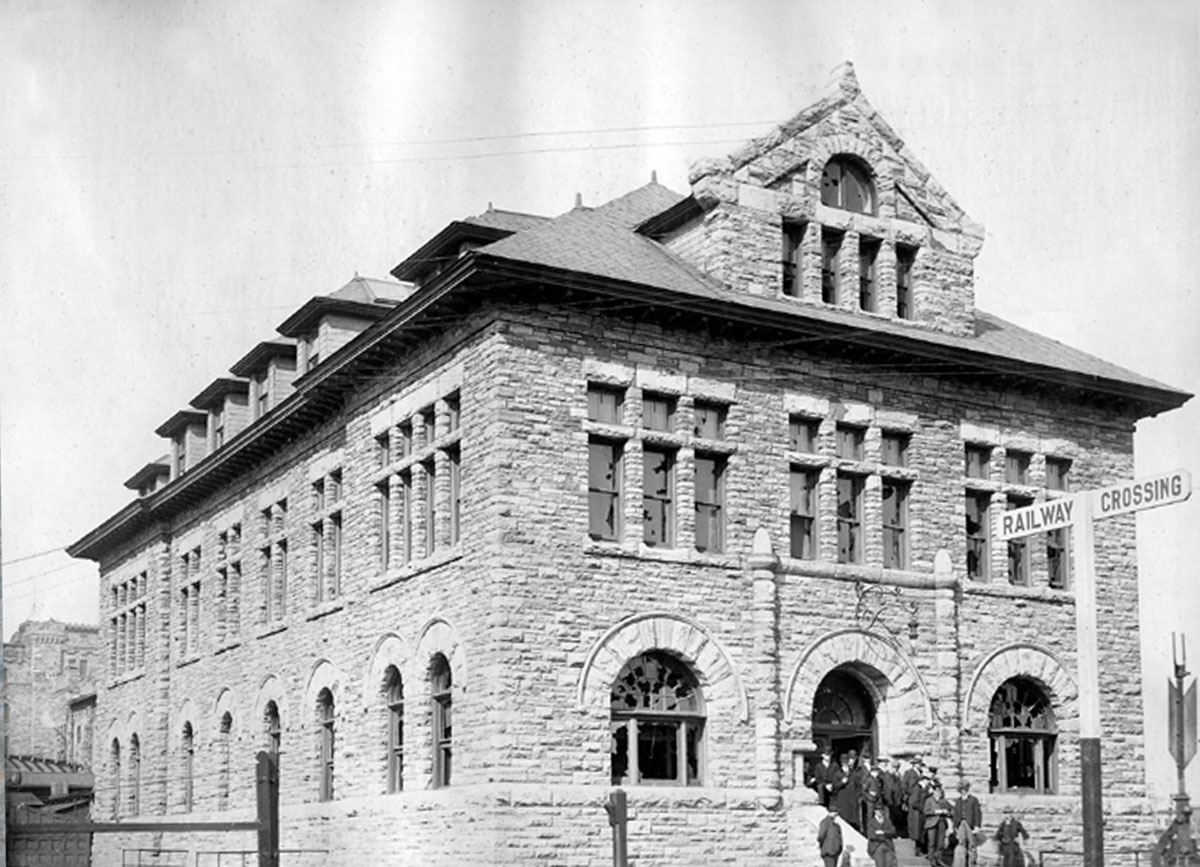

7. End of the Lake Superior Company

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 2000.66.5a

1903

In the above photo, men on the sidewalk look at the organised troops, which were largely unneeded. The use of armed forces to quell workers rebellions was a common phenomena in Canada at the time.

* * *

While largely peaceful, the presence of armed forces from the government was emblematic of the federal government's treatment of workers. By 1903, unions and unified workers organizations were no longer considered “illegal conspiracies,” however, unions still had very few rights. Union workers could be fired, and as took place at the Paper Company, employers could call in federal troops to prevent and stop rioting. The government’s involvement with the paper company riot was also due to the fact that the new division of labour had been created under the then Prime Minister William Lyon McKenzie. In 1900, the division of labour ratified specific legislation that demanded that certain trades engage in peaceful negotiations and mediation periods before entering into lawful strikes. The riots as Sault Ste Marie, were anything but lawful, and a show of force in the part of the government aimed to end that lawlessness.2

While relatively small and peaceful, the Clergue riot was part of a history of workers reclaiming their rights. For example, in 1872, workers in Ontario had been involved in the nine hour movement, a strike to end the allowance for 12 hour work days that began in Hamilton, Ontario.3 Leaders of the nine hour movement argued that employers could no longer be allowed to force workers to continue working past a nine hour day. While the movement was not successful, it paved the way for the rise of workers rights beginning in the 1880s. One particularly important organisation was the Knights of Labour was a secret society that began in the mid 1800s. Later made public, the Knights of Labour had a strong hold in Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic coast, and were not just a union. They had a guided interest in creating equal pay between genders, an eight hour work day, and health and safety for all workers. One other main mission for the Knights of Labour was in the education of workers, on rights, and in general, as they felt that workers needed to close the gap between those who were labourers and those who were business owners.4 While some twenty years after the dissolution of the Knights of Labour, the riots in Sault Ste Marie were part of larger class consciousness and changing mentality around workers and workers rights in Canada.

8. The Revisioned Paper Company

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X982.175.1

c. 1900

By 1905 the historic paper company building in the above photo had changed owners and withstood a riot. While the history of Sault Ste Marie often focuses on what the building represents, inside it was still a busy site of hard labour, workplace injuries, and workers rights.

* * *

In 1904, after a successful reorganisation, the company saw a significant growth and prosperity. Across the country, the growth of the railway business with the design for two national railways was felt in Algoma Steel. Algoma Steel from 1905-1915 produced over two million tons of rails.1 As well, an exponential growth of wheat exportation in Canada meant that demands for iron and steel in manufacturing were massive. Overall, the prosperity of the Lake Superior Corporation reflected the prosperity of the countries economy.

On the ground, workers in the factories faced the rapidly changing landscape of mechanisation and a growing boon for workers rights in the early 1900s. In steel factories, workers now had to navigate exceptionally dangerous hot, loud, smoky environments filled to the brim with machines and open hearth ladles that had the potential to kill them. Work had changed as a demand extremely skilled well rounded craftsmen were replaced by a demand for men who could do certain jobs such as melting and rolling, or the 'semi-skilled man.'2 Workplace injuries in steel factories were not well documented before 1912, therefore the injuries are relatively unknown. In 1912, however, Algoma Steel reported close to 400 work based injuries, and a workplace report from Nova Scotia demonstrated how critical experience was.3

"Most of the accidents are due to inexperience, and happen mostly to unskilled labourers about the large plants. Large numbers are injured by material of all kinds falling on their heads or feet, by being jammed between objects, by falling or tripping, and in many other ways, which can only be avoided by experience or when workmen get to know the dangers and mishaps liable to occur while they are at their work."4

Wages had become a major worry for Canadian producers, as they knew that they could not compete with American manufacturers who could charge significantly less for product because they paid their workers so little.

Further, in the early 1900s workers were still combating a brutal and grueling twelve hour work day in industries with continuous production. Even when being lobbied to consider workers rights, companies still rejected the eight hour workday.

For example, a Nova Scotia Commission on Hours of Labour in 1910 argued “that a day of twelve hours’ manual labor, or of twelve or ten hours of attendance on ovens, furnaces, and machines, amid the conditions of such an industry, is long, and leaves the man little time, inclination or energy for other interests”; but “as the business stands at present, the men cannot live on 8 hours pay, and the Company cannot afford 12 hours pay for 8 hours work.”5

Apart from the wage-saving behaviour the twelve hour workday had the benefit of controlling and limiting out of work behaviour. Men had to go home, go to sleep and go back to work, which meant that they could not drink or get up to mischief. As one company manager commented: “It seems to give them too much time off; too much chance of spending money or to get around."6 In Sault Ste Marie, the twelve hour work day would last until 1935.

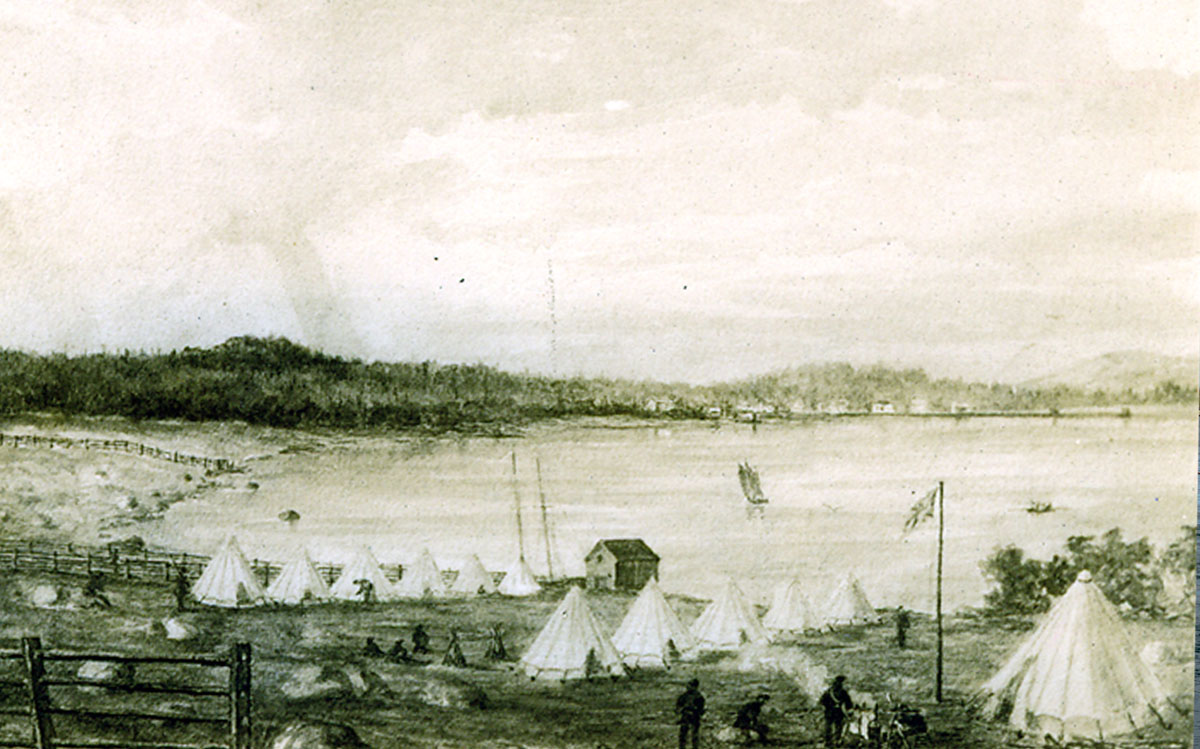

9. The Wolseley Expedition

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X978.16.27

The above painting by William Armstrong is a rendition of one of the most important moments for the Sault Ste Marie canal: the Wolseley Expedition. The party was made up of British and Canadian soldiers en route to the Louis Riel and the Red River Rebellion.

* * *

Since the 18th century various entrepreneurs and traders had tried to conquer the rapids. In the early 1700s, the Jesuits, some of Northern Ontario’s earliest missionaries put in a log flume to transport logs from Lake Superior down the St. Mary’s River, until it was washed away. In 1797, the Northwest Company placed a lock that was able to lift canoes into the upper portion of the river, and was in use until it was destroyed by American troops during the war of 1812. On July 3rd 1814, a small fleet leaves Detroit commanded by Patrick Sinclair in an effort to retake the nearby British occupied Fort Makinac. Travelling up the St Mary’s River, the fleet burns the trading post for the Northwest Company, the then abandoned Fort Joseph and the lock used to transverse the canal, both actions would have dramatic impact on the fur trade in Sault Ste Marie.1

However, in the history of Sault Ste Marie canal, the critical moment to the formation of the locks was the migration of Canadian and British forces in 1870 on their way to the Red River Rebellion, and their inability to cross the American Canal. In 1870, en route to Manitoba, British troops had sought to use the American Soo locks to continue onto Lake Superior. Yet, the Americans turned them down, arguing that they could not bring munitions into the locks. After a three week stalemate, General Wolseley was forced to unload the munitions and portage around the rapids. The stalemate and portage cost the Wolseley Expedition precious time to get to the Red River Rebellion.

The Wolseley expedition consisted of a number of British soldiers and Canadian militia as they travelled to take the former Rupert Land from Louis Riel and the Metis forces in Manitoba. The named Red River Rebellion at Fort Garry was brought about by the confederation of Canadian and the appointment of William McDougall, an English speaker, as the overseer of the newly purchased land. The vast majority of occupants in these lands were french speaking Metis, and such an anti-francophone appointment further alienated communities who had no allegiance to the recently formed government. While the land had originally been purchased by the Hudson's Bay Company and called Rupert's Land, the people of the land including the indigenous communities were not included in the decision of this sale. Under the leadership of Louis Riel, a formal colony was formed that sought to rebel against the Canadian government, which culminated in the peaceful surrender of Fort Garry under the Wolseley expedition. The expedition was formed partially by anti-metis and anti-Riel sentiments in Toronto.2

When General Wolseley arrived at Red River, he found that Louis Riel had fled, and was able to take control of the settlement. For the British soldiers, the stalemate of three weeks had had a disastrous effect on their ability to capture Riel, and reminded them how quickly the Americans could limit British movement. The events of the portage required to transverse the rapids was a guiding force in the building of the Sault Ste Marie Canal on the Canadian side of the River. 3

10. Needing a Canal

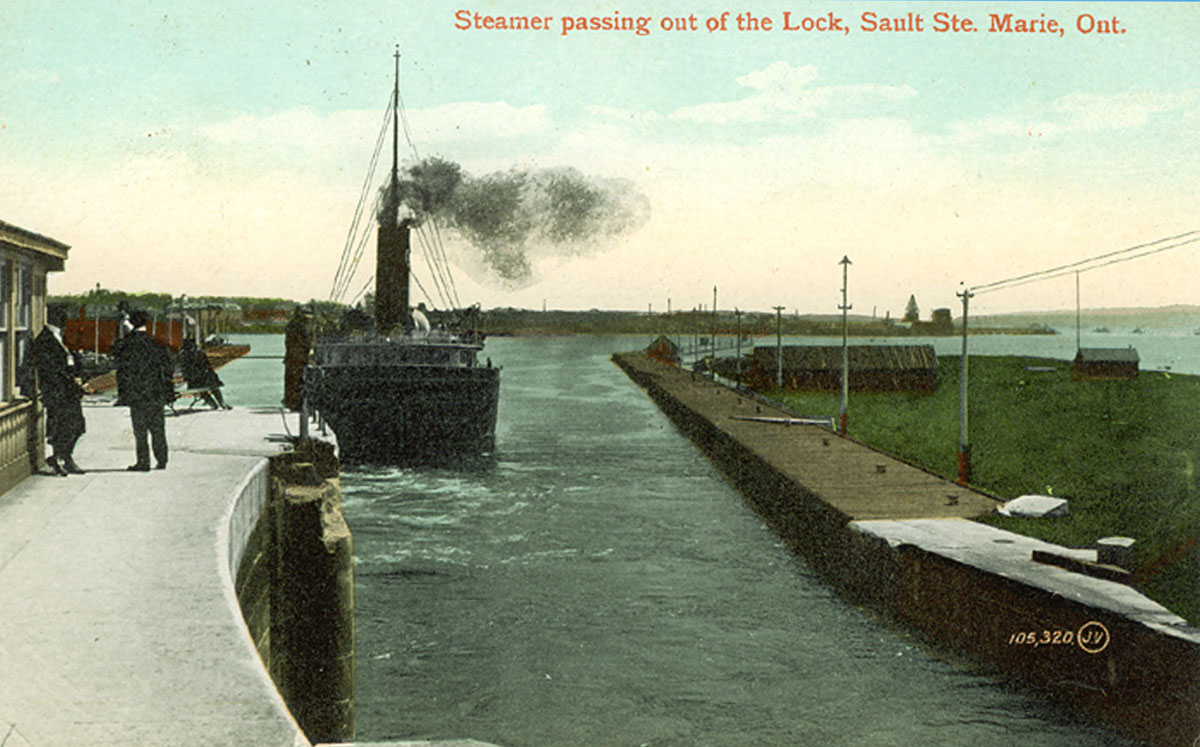

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 992.77.12

c. 1905

The above picture shows a ship leaving the Sault Ste Marie canal in 1905. The canal was built to give Canada complete freedom in the waterways from Lake Superior to the Atlantic, and free them from American control.

* * *

Tupper was recorded saying “The time has come when we should not be in the humiliating position in which we found ourselves before.”1

The evidence for the Canadian displeasure at American control was also present in the newspapers, reflecting public sentiment.

St. Catharine's Constitutional wrote, reflecting mood in Ontario: "Of all Governments within the pale of civilization, the Yankee Republic is one of the most uncertain to deal with, and is the most devoid of dignity in its administration... Their conduct in this matter should teach us another lesson of not expecting favours at their hands and it also tells us that we should have a canal of our own at Sault Ste. Marie build this season."2

Yet, canal planning had taken a back seat to the desire for John A Macdonald to consolidate and connect all of Canada through a railway. In the 1870s, alongside the Red River Rebellion, was the economic turmoil of the West Coast. During the 1860s, the gold rush and gold mines had brought significant prosperity, yet in the later half of the 1860s such wealth had run out, and the province was faced with poverty. America’s most recent purchase of Alaska, alongside the absorption of some of British Columbia’s debt, lent weight to the fear that the US could annex much of Canada’s west coast. The goal of the McDonald government during the 1870s, was therefore to create a Canadian west coast, and connect one end of the country to the other with a railroad.3

However, in the late 1880s, the House of Commons returned to the issue of the St. Mary’s River, and the absence of a Canadian lock. In 1888, construction for the lock was granted to two men: Hugh Ryan and Micheal Haney, exceptionally successful railway builders. Both men had immigrated in the mid century from different parts of Ireland, and had met building the Red River Valley railway in 1866. While the contract for the Soo canal belonged to Ryan and Co., the company that Hugh Ryan had started with his brother, Haney was brought on as head of construction. Unlike others in his field, Haney stayed on site for the entirety of construction, living alongside the men and the canal for the four years it took to complete. Haney was known for an unwillingness to ask a man to do a task that he himself would not undertake.4

Construction for the lock broke in 1889 but was not completed until 1895. When constructed the canal was the largest in the world, measuring 1.1 miles in length and 150 feet wide. The canal was constructed during a period of technological transition, manifested by its completely electrical lighting, and electrical motors, harnessed by the hydroelectric dam.5 The completion of the canal meant that Canada had a complete transportation system of its own from the Atlantic to the Pacific

11. Building the Canal

Sault Ste. Marie Museum X988.27.5q

190

In 1890, work on the Sault Ste Marie Canal had begun, and some 800 hundred men would continue the work for four years. The above photo captures some of that labour.

* * *

The vast majority of canal workers in Sault Ste Marie, like other canals, were immigrants from Ireland and other parts of the United States, having immigrated to North America against poverty and in search of employment in their home countries.2 The migration of workers raised a two-prong problem and solution for the industrialization of Canada. Immigrants had very little access to farmland, or the means to purchase such. With the closure and unavailability of farm lands for those who had come off the boats from places such as Ireland and Britain, many sought work in construction, with canals being one of the most stable. 3

With much of the workforce consisting of migrated labour forces, workers had their own communities during the construction of the canals. Indeed, during the 1850s, canal working life was considered brutal and violent, as many of the Irish communities formed their own groups that fought against the injustice of cheap and often dangerous labour. Living in shanty-town communities with hundreds of other men, violence was commonplace, alongside drinking and illnesses such as diphtheria, and cholera.4 In the heyday of canal work in the mid 1800s, the end of a contract period later meant that men would starve when the work had been completed. While some would go onto work on the boats or the canals, others would continue in wage labour similar to that of the canal building itself.5

While the construction of the Sault Ste canal occurred after much of canal culture had begun to die out, we know that certain sentiments were still true. In the construction of the canal, some 800 men were employed, many immigrants from Ireland, and the work was still labourious and hard.

Osbourne and Swainson note that “working conditions must have been horrendous but they produced excellent results. An average 400 men worked on excavation during the peak construction years. At least another 200 men worked in the quarries while 200 more served as stone cutters and masons at the canal site. Machinists, electricians, carpenters, enginemen and dynamite experts were more specialized crafts mixed in with the general masses of haulers and labourers."6

Canal workers, likewise, still rebelled against their leaders, attempting to assert control over their own selves and labour. For example, when Hayne left the site on a short absence, canal workers began to strike at what they believed to be an unjust firing of a stonemason for faulty work. When Hayne returned, he asked the workers to assess the workmanship of the stonemason in question, and if not faulty, he would fire the foreman instead. When workers found fault in the work, they ended the strike.7

Likewise, the diseases that occurred in the mid 1800s were still part of the Sault Ste Marie canal workforce, and thereby the surrounding town population. During the period of 1893 to 1908, the population of Sault Ste Marie grew exponentially, from 2000-8000 individuals. The shantytowns of lumber mills and canal workers meant that the town was at risk for epidemics of cholera, diphtheria, smallpox, and typhoid.8 Further, the facilities for the care of such illness were very few. No hospital existed and all that was placed was an isolation hospital-shanty with six beds outside of town.9

After a long and often difficult battle the lock as Sault Ste Marie was opened on September 7th 1895, with the first vessel to enter the lock being the steamer the Majestic. What had been labelled a scar on the landscape had been turned into a fully functioning lock with the ability to provide Sault Ste Marie with access to the Atlantic.

"Contemporary photographs help to fill out this picture. The site was a muddy irregular scar of giant proportions cut across St. Mary's Island and the scene of considerable activity as the scores of men went about their varied specialized tasks. Only the sounds are missing. The air must have been full of the detonations of the blasting operations, the cries of men and animals engaged in the hauling and carting of the supplies, and the steady beat of the pumps 'unwatering' the deep excavation for the lock." 10

12. Breaking the Canal

Sault Ste. Marie Museum 994.84.8

1909

In 1909 a collision between three boats in the locks had a disastrous effect on the locks. In the above image, we can see the water rushing down the locks as high speed.

* * *

On June 9th three ships were involved in a crash in the locks. The Assiniboia was tied into the lock from above, the Crescent City was entering the lock with her stern over the upper miter sill, and the Perry Walker was entering the lock from below. It was the Walker, misunderstanding signals between captain and engineer that struck the southern pier at a speed of six miles per hour and crashed into the southern gate. The resulting damage caused a drop in water that moved at 15 feet per second.2

For travellers, the incident was considered thrilling "Pandemonium reigned on the Assiniboia for a time after the accident. Several people fainted and others were so overcome that stimulants had to be administered. One passenger attempted to jump overboard into the seething waters and was only dissuaded from doing so by the mate who, when other means failed, floored the man. Another passenger threw his trunk overboard. The officials of the Assiniboia feel that their escape was almost miraculous... one of them stated that, had the Crescent City struck the Assiniboia in the centre below the mark the boat would almost certainly have been cut in two... Some of her passengers apparently supposed this method of locking was the usual one for they are reported to have continued to snap their cameras as they were shot along the canal.”3

After the rebuilding of the lock in the 1909, Sault Ste Marie's canal system was a critical part of the shipping and transportation well into the beginnings of the Great War.

13. Protecting the Canal

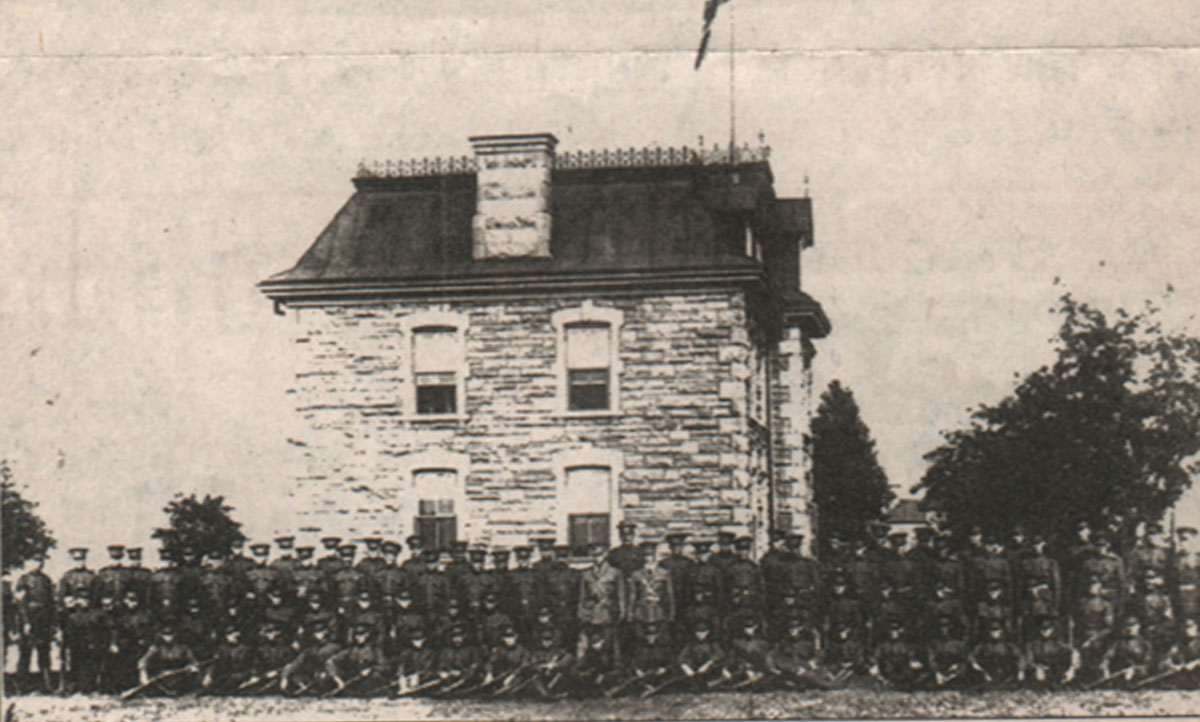

1914

In 1914 when Canada entered the Great War many Canadians signed up. The above image shows the first Sault Ste Marie regiment preparing for departure.

* * *

On the home front, the early parts of the war were difficult on an already troubled economy Canadian economy.4 While the construction of the lock at Sault Ste Marie was viewed as a necessary and jubilant time, the challenges of industry in the early 1900s still followed. Francis Clergue’s Empire would still rise, and later fall. In the early part of the 1900s, Sault Ste Marie steel, a major industry in the town was experiencing a serious depression, the demand for railways had died out, and the expansive facilities created by Clergue were quiet. Sault Ste Marie, however, would play a major role in the Great War, not only in manpower, but in the ability to create and ship the munitions to the front.5

For Algoma Steel, whose major production were railways and munitions already, the switch towards only munitions put significant demands on facilities that were not prepared to handle such changes. Munitions loads required the use of new tools, and new skills, neither of which the company had possessed. Likewise, the traditional high phosphorus ore Bessemer method for making steel was changed towards open hearth, requiring a new and expensive furnace. However, Algoma was not alone, as cross the country, the exportation of open-hearth steel grew from 642, 062 tons in 1912, to well over a million tons by 1916. For Algoma, the specialization in Bessemer meant that rapid changes had to its production to keep up with the demand.6

By 1918, Sault Ste Marie had been a critical and influential part of the war, from sending along munitions to the contributions of strong men on the front. The loss of life during the Great War was memorialized not only by the cenotaph in town, but in cairns at the Paper company, as workers mourned the loss of their friends and family.7 Walking into the next hundred years, Sault Ste Marie as a newly minted city would become an important staple for the Northern Ontario economy and landscape, not only in steel and industry, but in culture and the arts, providing a bridge to the rest of North America.8

Endnotes

1. An Ancient Gathering Place

1. James Marsh, "St Marys River (Ont)," The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 Feb. 2006, online.

2. "A Traditional Gathering Place," Town of Sault Ste. Marie Website, online.

3. Osborne & Swainson, The Sault Ste. Marie Canal, (Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986), 10.

2. The Age of the Canoe

1. E.T. Adney and H.I. Chapelle, Bark canoes and skin boats of North America, (Skyhorse Publishing Inc, 2007), 135-138.

2. Adney and Chapelle, 142-144.

3. Carolyn Podruchny, Making the voyageur world: Travelers and traders in the North American fur trade, (University of Nebraska Press, 2006), 20.

4. Podruchny, 3.

5. E.W. Morse, Fur trade canoe routes of Canada: Then and now. (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1969), 22.

3. The Fur Trade Post

1. Podruchny, 26.

2. Podruchny, 26.

3. Morse, 22-23.

4. Podruchny, 42.

4. End of an Era

1. Sault History Online, "Sault Ste. Marie before the arrival of F.H. Clergue," City of Sault Ste Marie, online. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/Clergue_Before.html

2. Thor Conway, "An Unusual 19th Century Portrait Pipe from Northern Ontario." Ontario Archaeology 43-46 (1985): 63

5. The Riot of 1903

1. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/Clergue_Before.html

2. Iles, Elizabeth A. Ask the Grey Sisters: Sault Ste. Marie and the General Hospital, 1898-1998. Dundurn, 1998. p. 16

3. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/Clergue_Process.html

4. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/francis-clergue, accessed January 24th 2020

5. McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984. pg 2

6. An Empire Crumbles

1.http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/Clergue_Collapse.html

2. McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984.

3. McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984. p. 35

4. Ibid, pg. 38-39

7. End of the Lake Superior Company

1. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/Clergue_Collapse.html

2.https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/working-class-history

3. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nine-hour-movement

4. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/article/knights-of-labor

8. The Revisioned Paper Company

1. McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984. p 50-51

2. Heron, Craig. Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-class History. University of Toronto Press, 2018., p. 163-165

3.Heron, Craig. Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-class History. University of Toronto Press, 2018., p. 170

4.Heron, Craig. Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-class History. University of Toronto Press, 2018., p. 171

5. Heron, Craig. Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-class History. University of Toronto Press, 2018., p. 168

6. Heron, Craig. Working Lives: Essays in Canadian Working-class History. University of Toronto Press, 2018., p. 16

9. The Wolseley Expedition

1.Magnaghi, Russell, and Ted Bays. "The Upper Country in the War of 1812: A Chronology." Upper Country: A Journal of the Lake Superior Region 1, no. 1 (2013): 6. Pp 55

2. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/culture/clmhc-hsmbc/res/doc/information-backgrounder/Expedition_Riviere-Rouge-Red_River_Expedition

3. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/on/ssmarie/culture/histoire-history/site

10. Needing a Canal

1. Hoskins, S. and Joyce, J., 2014. The Canal At Sault Ste Marie: The South Shore Quarry's Contribution to Canadian History. FriesenPress. P 16

2. Osborne, Brian S. & Swainson, Donald. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986 pg 36

3.Hoskins, S. and Joyce, J., 2014. The Canal At Sault Ste Marie: The South Shore Quarry's Contribution to Canadian History. FriesenPress. Pp 16-17

4.Hoskins, S. and Joyce, J., 2014. The Canal At Sault Ste Marie: The South Shore Quarry's Contribution to Canadian History. FriesenPress. Pp 16-17

5. Reynolds, Terry S. "Robert W. Passfield, Technology in Transition: The" Soo" Ship Canal, 1889-1985 (Book Review)." Technology and Culture 31, no. 4 (1990): 880

11. Building the Canal

1. MacKinnon, M., 1996. New evidence on Canadian wage rates, 1900-1930. Canadian Journal of Economics, pp.114-131.

2. Bleasdale, R., 1981. Class Conflict on the Canals of Upper Canada in the 1840s. Labour/Le Travail, 7, pp.9-39.

3. Ibid

4. Way, P., 1993. Evil Humors and Ardent Spirits: The Rough Culture of Canal Construction Laborers. The Journal of American History, 79(4), pp.1397-1428.

5. Way, P., 2009. Common Labour: Workers and the Digging of North American Canals 1780-1860. Cambridge University Press. Pp. 265-274

6. Osborne, Brian S. & Swainson, Donald. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986 pg 76

7. Hoskins, S. and Joyce, J., 2014. The Canal At Sault Ste Marie: The South Shore Quarry's Contribution to Canadian History. FriesenPress. P 8

8. Iles, Elizabeth A. Ask the Grey Sisters: Sault Ste. Marie and the General Hospital, 1898-1998. Dundurn, 1998. P 51

9. Ibid; Pg 37

10. Osborne, Brian S. & Swainson, Donald. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986, pp 54

12. Breaking the Canal

1. Osborne, Brian S. & Swainson, Donald. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986, pp 85

2. Townsend, C.M., 1909. The Accident to the Canadian Canal Lock Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. Professional Memoirs, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, and Engineer Department at Large, 1(3), pp.232-239.

3. Osborne, Brian S. & Swainson, Donald. The Sault Ste. Marie Canal. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1986 , pp 89.

13. Protecting the Canal

1. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/WW1_WW1.html

2.http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/WW1_Index.html

3. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/WW1_Forestry.html

4. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-world-war-wwi

5. McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984., p 59

6.McDowall, Duncan. Steel at the Sault: Francis H. Clergue, Sir James Dunn, and the Algoma Steel Corporation, 1901-1956. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1984., p 59-60

7. http://www.cityssm.on.ca/library/WW1_Home.html

8. https://saultstemarie.ca/City-Hall/City-Departments/Community-Development-Enterprise-Services/Community-Services/Recreation-and-Culture/Historic-Sites-and-Heritage/Local-History.aspx