Walking Tour

Living on the Frontier

Tales from Early Fort Frances

By Andrew Farris

Library & Archives Canada 3310180

Welcome to Fort Frances, a town filled with rugged history, where the whispers of fur traders, the rumble of paper mills, and the echoes of rowdy frontier hotels once came together along the banks of the Rainy River.

Over the next two hours, we’ll embark on a 2.5-kilometer journey through time, starting at what was once the town's main business district, along Front Street. Here we'll hear tales from the hotels and the growing pains of a remote frontier town finding its way towards the future.

These early days ended with the great fire of 1905 which devastated this district, and led the town to shift its centre of gravity towards Scott Street, our next destination. On Scott Street we'll hear Fort Frances's stories of bank robbers, war heroes, and community builders.

Finally we'll head south, past the courthouse and LaVerendrye Hospital, and stroll along the Rainy River. Along the way we'll learn about rum runners, lumberjacks, tug boat captains, and more. The tour will end at Sorting Gap Marina.

Saddle up for a journey through this town's rich past.

1. Welcome to Fort Frances

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1940

We begin our adventure just past the International Bridge, which connects Fort Frances with International Falls, Minnesota. In this historic photo, we see two mounties in their bright red uniforms standing beneath the ‘Welcome to Canada’ sign. The sign was put up with much celebration in 1948 and quickly became a popular photo spot for American tourists and for locals. It was demolished in 1976 after falling into disrepair.

Before we dive into the modern history of Fort Frances, which is the focus of this tour, let's step further back in time to the First Peoples and fur traders.

* * *

French explorers and fur traders were the first Europeans to use this river highway to travel west past the Great Lakes. This site where we are now standing, between the head of Rainy Lake and the great falls just west of us, was a natural stopping point. In 1731 Pierre Gaultier de Varennes established Fort Saint Pierre just beside the lake to our east, at today's Point Park and Agency One lands. He continued pushing west and set up a new fort on the Lake-of-the-Woods, using the fort here as a supply depot. That new fort at Lake-of-the-Woods soon overshadowed Fort Saint Pierre, and it was soon abandoned.

However, it wasn't long before a new wave of fur traders arrived. In the 1780s the Northwest Company established Fort Lac la Pluie as its supply depot for Arctic-bound traders. It was located a short distance from here, just downstream of the falls to the west.

After the War of 1812 the border between the United States and what-was-then British North America was drawn down the middle of the Rainy River. Around the same time the Hudson's Bay Company absorbed the Northwest Company and took over Fort Lac la Pluie, moving it closer to the falls.

In 1830 the governor of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) was touring his company's vast and remote territories with his young new bride; Lady Frances Simpson. It was a sort of honeymoon trip for the couple, but not the kind you'd think of today: They along with the rest of the HBC men in their party were up at 2am to begin the day's journey and paddled until at least 8 at night.2

They rapidly passed by the HBC's fort here on their way west. Lady Simpson's son found some time to appreciate the location, writing: “The establishment is delightfully situated on the east bank of the river, overlooking a beautiful waterfall to the south, also the American post, on the opposite side, and a long reach of this noble stream to the north.”3

After this event the HBC decided to rename the fort in Lady Frances's honour: Fort Frances had its name.

For a few decades the outside world took little notice of the sleepy Fort Frances at the head of Rainy Lake. As the end of the 1800s approached that started to change.

2. Starting a Town

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1904

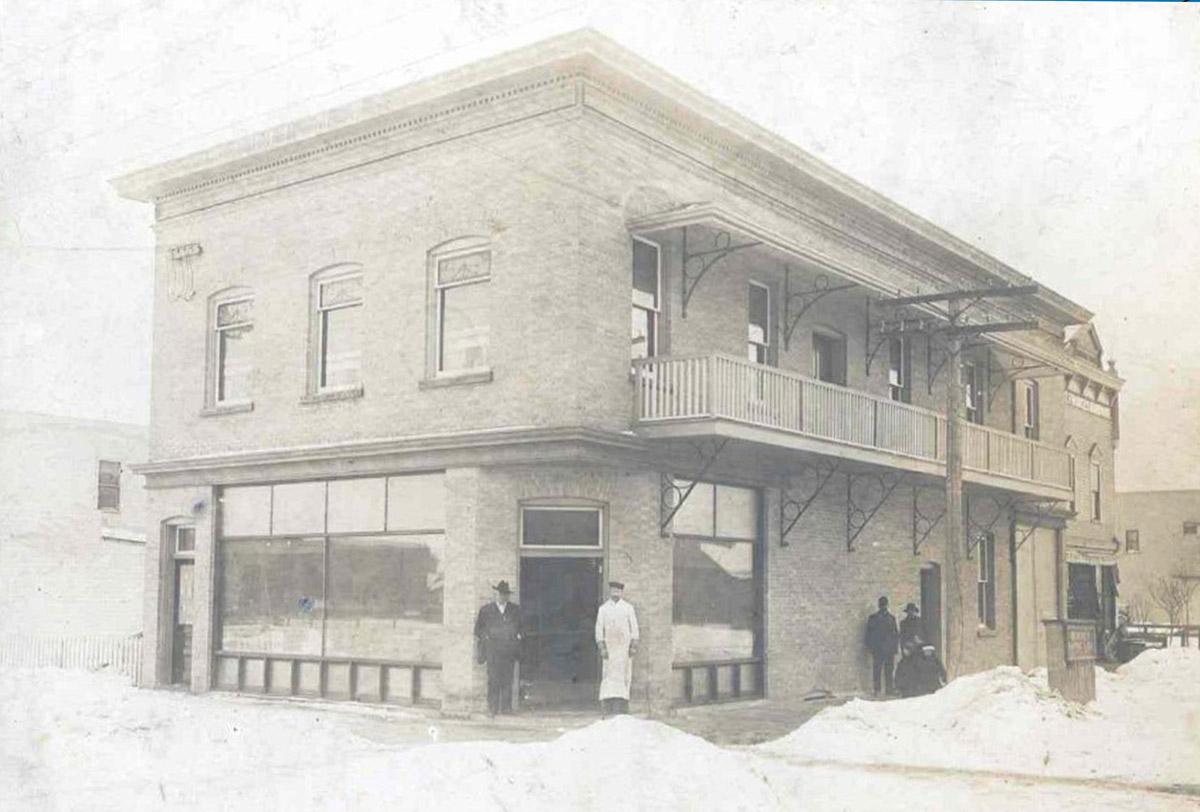

This lot was once the location of Christie's Meat Market. It was built in 1903, the same year that the 75 eligible voters that lived here (men over the age of 21) elected to officially incorporate Fort Frances as a town.1 Louis Christie was a popular butcher and prominent entrepreneur in Fort Frances in the 1890s—people called him the Meat King of the Rainy River.

He built his new meat market here after his previous market had burned down. The spot was significant for another reason: it had previously been the site of the Knox Church, the oldest church in the parish, dating back to 1884. Unfortunately, in 1903 it also burned down (it happened a lot in those days). So Christie bought the lot in the expectation that this was going to be the heart of the new town's business district.

* * *

At that time millions of European immigrants were pouring into Canada's prairies to set up homesteads. Today we live in an age where we'll often spend hours reading reviews before choosing a hotel to stay in for just a couple nights, so to our eyes it may seem strange that few of the immigrants in those days had any real concept of where they were going and what kind of life they had signed up for on the prairies. Oftentimes they only needed the slightest encouragement to completely change their destiny. For no small number of the people that chose to settle in Fort Frances, that encouragement came in the form of a slickly produced pamphlet pressed into their hands at a train station. That pamphlet announced the unfathomable opportunities in and around Fort Frances for farming, lumbering, and mining, and the great wealth and happiness one could find here—it sounded like a better bet than Saskatchewan. Some needed no more convincing and immediately diverted towards this far corner of Ontario to start a new life.2

By 1903 about 500 people called Fort Frances home, and they were enthusiastic about the industrial potential of the area. The Rainy River's mighty falls could be harnessed to provide hydroelectric power for a pulp and paper mill. The mill would have no shortage of lumber, forests stretched for hundreds of kilometres around. These could provide hundreds of jobs for millers and lumberjacks.

The 'Rainy River Meat King's' bet that this remote fur trading post was about to grow and prosper turned out to be a good one. By 1910 this market boasted of being the "largest meat market east of Winnipeg."3

3. The Emperor Hotel

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1908

Here at the corner of Church and Central Street is where the Emperor Hotel once stood. At the time Central Street, was known as Front Street, and in those early days it was the heart of Fort Frances.

The hotel was built in 1907, one of several grand hotels around this area at a time when royal names were popular—the others were the Palace (located where the pulp mill parking is now), Prince Albert (which was located right across from Christie's Meat Market) and the Monarch (which we will see later in this tour).

It was the largest hotel in town and unsurprisingly advertised itself as the "best hotel" too. As Julie Byzewski writes, the hotel's owner Jim Harty "boasted of finest hot and cold collations (of food) that could be procured, unadulterated liquors, and the finest cigars that money could buy (at ten cents each)." It was "beautifully situated overlooking the big Mill, with everything modern and up to date, large airy rooms, comfortably heated, the home of the comercial traveller, with a bright cheery dining room in connection.

* * *

During the Influenza pandemic of 1918 there were at least 200 cases in the town, overwhelming the hospital. The Emperor Hotel was set up as an emergency treatment centre under the guidance of Nurse Kaine, a member of the Order of Grey Nuns. In addition to ordering social distancing and shutting down public events, the public was told to:

"Avoid contact with other people; Avoid chilling of the body or living rooms of temperature below 65 deg or above 72 deg.; Sleep and work in clean, fresh air; Keep your hands clean and Keep them out of your mouth; Avoid expectorating in public places; Keep your feet warm."

Though there were some reported deaths, the pandemic soon subsided, schools were reopened, and the ban on public gatherings was lifted.1

The innkeeper Jim Harty passed away in 1927, but the Emperor lasted for many more decades, despite major fires in 1952 and 1953 that destroyed the Church Street annex and the third floor.

Finally in 1982 the hotel was demolished and replaced with the Ontario Tourist Information Centre.

Though the Emperor is gone, its memory is preserved in a nearby mural that shows Fort Frances’ historic hotels. These buildings reflected the town’s growth and ambition during its early development.

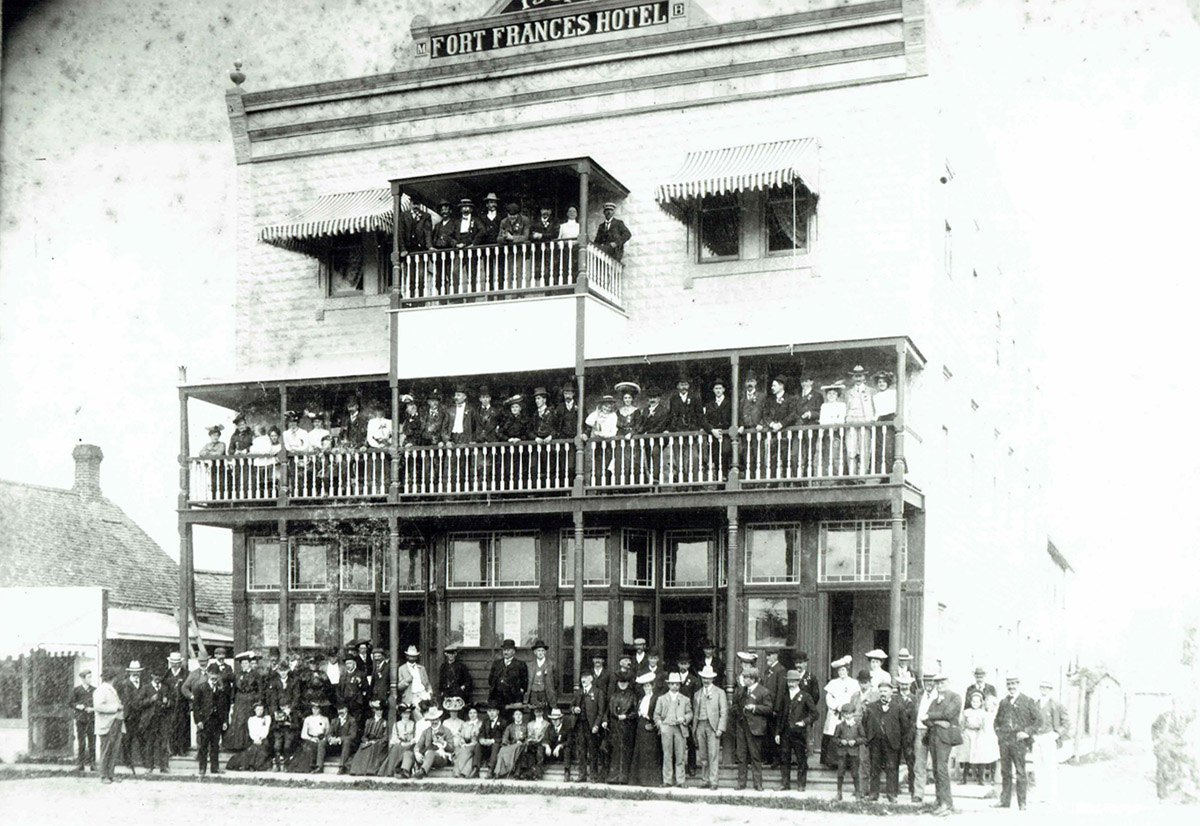

4. The Fort Frances Hotel

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1900

Here we see a crowd gathered in fine clothes on the steps and balconies of the first Fort Frances Hotel. It was another of the major landmarks that once lined Front Street. As one resident remarked on those early days, "it was a typical lumberjack town, there were no street lights, only a kerosene lantern at the corner of Scott Street and Portage Avenue and it was lit only part of the time."1

This Fort Frances Hotel (the first one) burned down in 1905. The owner was not discouraged however, and built a second Fort Frances Hotel on Mowat Avenue. It was open by the end of the year.

* * *

The lumberjacks spent much of the year out in the woods, but when the season ended they received their pay and tended to head straight to hotels like the Fort Frances—where the whiskey and beer were cheap and hopefully unadulterated. In those days before a bridge across the river, they could also take the hourly ferry to International Falls.

In 1908 the International Falls Echo reported that the: "breaking up of the lumbercamps of the Canadian Northern east of Fort Frances has filled that town during the past week. Enough of them have strayed to this side to keep the ferries busy day and night, and to make business lively in the saloons."

In a follow-up report a few days later it reported that "the lumberjacks had moved on, they made the town lively for a week and it is figured by some that they distributed $10,000 here during that time."2

5. The Great Fire

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1895

This photo looks back across the street and shows the Alberton Hotel during Front Street’s heyday. To the right, you can just make out the third storey of the Fort Frances Hotel. The Alberton also housed the City Bakery, S. Haryett General Merchants, and Breckon’s soft drink emporium—the first of its kind in town

Of course you will have noticed that none of the buildings we've seen on Front Street so far have survived to the present. A big reason for that is that most of the town's business district burned down on June 16, 1905.

* * *

Eventually, the town accepted a design from a Minneapolis company and ordered a Knott Fire Engine. It arrived in May 1905. But because of a dispute with the manufacturer, nobody was allowed to touch it. The brand-new engine just sat there. A month later, the business district burned down—right next to where it was sitting.

The fire, likely started by a lantern in a clothing store, tore through the downtown. "The fire destroyed Frank Strain's barber shop, Charles Nelson's clothing store, Wells' hardware, the Couchiching Hotel, Christie's Butcher Shop, the Alberton Hotel, Fraleigh's Drug Store, H. William's General Store and Caspar's photography studio."2 Also damaged was the first Fort Frances Hotel. Damages were estimated at about $20,000, ironically the same amount set aside for the fire hall and engine.

Getting a fire department up and running suddenly became town council's top priority. The town hurriedly resolved their dispute with the engine manufacturer (no doubt an awkward conversation), and within days started construction on a fire hall and founding the volunteer fire brigade.

While many more fires would occur in Fort Frances's history, none were as devastating as the one that tore through the Front Street business district. At the time some businesses had already started popping up on Scott Street. Due to the lower land prices, as the town rebuilt most of the new construction was centered there, and that's where the town's centre of gravity would move for the century to follow.

6. Growing Pains

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1919

The Monarch Hotel once stood on this corner of Scott and Front Street (Central Avenue today). It wasn't actually built here, but in the town of Mine Centre over 60 kilometres away. In 1906 the Monarch's owner decided to move to Fort Frances and rather than build a new hotel he just took apart the building and floated it over the Rainy Lake to Fort Frances, where he reassembled it on this spot. Here the Monarch stood for over 80 years, changing its name in 1947 to the Irwin Hotel and getting a coat of pink paint.

Records of Fort Frances's town council from around this time show us a society with quite different concerns than we have today.

* * *

Cows were one of the town’s biggest problems. They ran through yards, trampled gardens, and, worst of all, destroyed sidewalks. The Fort Frances Times wrote: “it is hoped the cow by-law will be strictly enforced by the town authorities during this season as nothing is more annoying to residents.. "

To keep them from running rampant their owners would tie them to trees and posts all over town, and it was an apparently common annoyance for a pedestrian to "take a tumble while crossing over some chain or rope fastened to a peg or tree with a cow at the other end." As a result the Times demanded: "These animals should not be permitted on the streets in the residential portion of the town either at large or tethered to stakes."

Since these same complaints about cows and sidewalks are recorded year after year in the 1900s and 1910s, it seems the by-laws had little effect.

Kids causing trouble at night became such a problem that the town set a curfew. But enforcing it was a constant challenge. It took so much police time that sal aries had to be raised. The growing police department (3 constables in 1911) frequently chased off vagrants that were trying to cheat lumberjacks. They had their hands full breaking up illegal brothels. The Times drily reported on one raid on a house of ill repute where police discovered "two women, three men, and two pigs."1

7. Rising from the Ashes

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1908

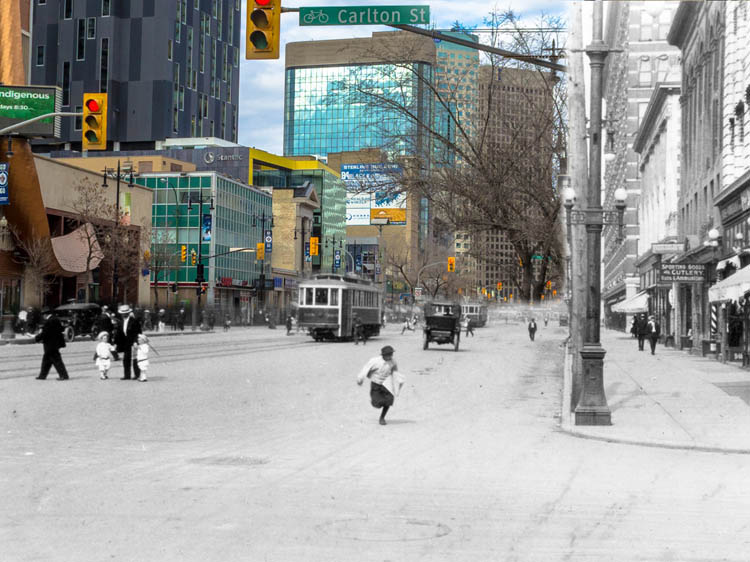

The fire of 1905 reduced Front Street's business district to cinders, but the people of the town were undeterred. Reconstruction began immediately, and as we can see from this photo, much of it was occurring on Scott Street where the land was cheaper. The first more permanent brick buildings are going up, and the water tower in the distance indicates the establishment of a modern waterworks.

* * *

"In June of last year a most disastrous fire visited the business portion of the town, wiping out the hotels and stores; but Phoenix-like there has arisen out of the ashes a greater and better class of buildings. We now boast of three of the finest hotels to be found in western Canada, containing steam-heat, electric light fixtures, electric bells and telephones. We have a splendid local telephone system, and in a short time will have sewage and water-works, all of which will be owned and controlled by the town.

"In closing these few remarks as to Fort Frances, we cannot do so without a reference to the progressive nature of our citizens. A complete fire apparatus, a new town hall and fire hall, with an up-to-date opera-house, constructed from native stone and brick, will give to the traveler and stranger that feeling of stability and security which inspires all who visit our town.

"With a future before us, and the certainty that Fort Frances will be the greatest flour milling and manufacturing centre of the great Canadian northwest, we have no hesitation in extending a cordial invitation to all who are looking for investments, or a field for manufacturing, or a place in which to spend the balance of their days, to come and see us."1

8. "Stick 'em up!"

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1924

Looking down Scott Street in the 1920s, we see the town has grown and cars have become commonplace. At the far left is the newly-built Dominion Bank, which moved into that distinctive building in 1922. That building was torn down in 1984 to make way for the present TD bank building.

On New Year's Eve 1930, the Dominion Bank was the scene of a brazen mid-day robbery by a 16-year-old boy.

* * *

Constable Wall still hadn't heard about the robbery and was actually just offering him a ride. When the boy got in, he thought he had been caught and immediately apologized and confessed to the shocked constable, who searched him and found the stolen cash and a gun.

Justice was swift. By the next morning—New Years Day—he had pled guilty in front of the magistrate and was handed down a harsh sentence: five years in prison and 20 lashes.1

Corporal punishment may sound shocking to us today, (as might a trial and sentencing first thing in the morning on New Year's Day, the day after the crime was committed) but the Canadian Criminal Code didn't abolish lashes as a punishment until 1972.

The boy got lucky however. His distraught mother pleaded with the court not to give him the lashes, and that part of his sentence was never carried out.

9. The Rainy Lake Hotel

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1960s

Here we see the famous Rainy Lake Hotel, once Scott Street's crown jewel.

The Rainy Lake Hotel came from the Fort Frances Hotel Company's desire to build a modern tourist hotel that would anchor the growing community. In 1928 they raised $150,000 ($2.3 million today) and hired the prominent architect Arthur Hanford to design a landmark that reflected the optimism of the Roaring 20s.

Hanford's design blended Spanish-inspired elegance with cutting-edge amenities that would be a symbol of prosperity in this frontier town.

The hotel's grand opening on June 15, 1929 was presided over by the Canadian Minister of Labour, and included a lavish banquet and dance in the gorgeous ballroom. The Fort Frances Times called the new hotel “a testament to the town’s progress.” Eager crowds marveled at the cream, tan, and salmon brick façade, which was accented by white stone trim and a red-tiled roof. The exterior also had a wrought-iron balcony, ornamental stonework, and a tower at the top. The iron balcony was preserved and can today be seen in Rainy Lake Square.

* * *

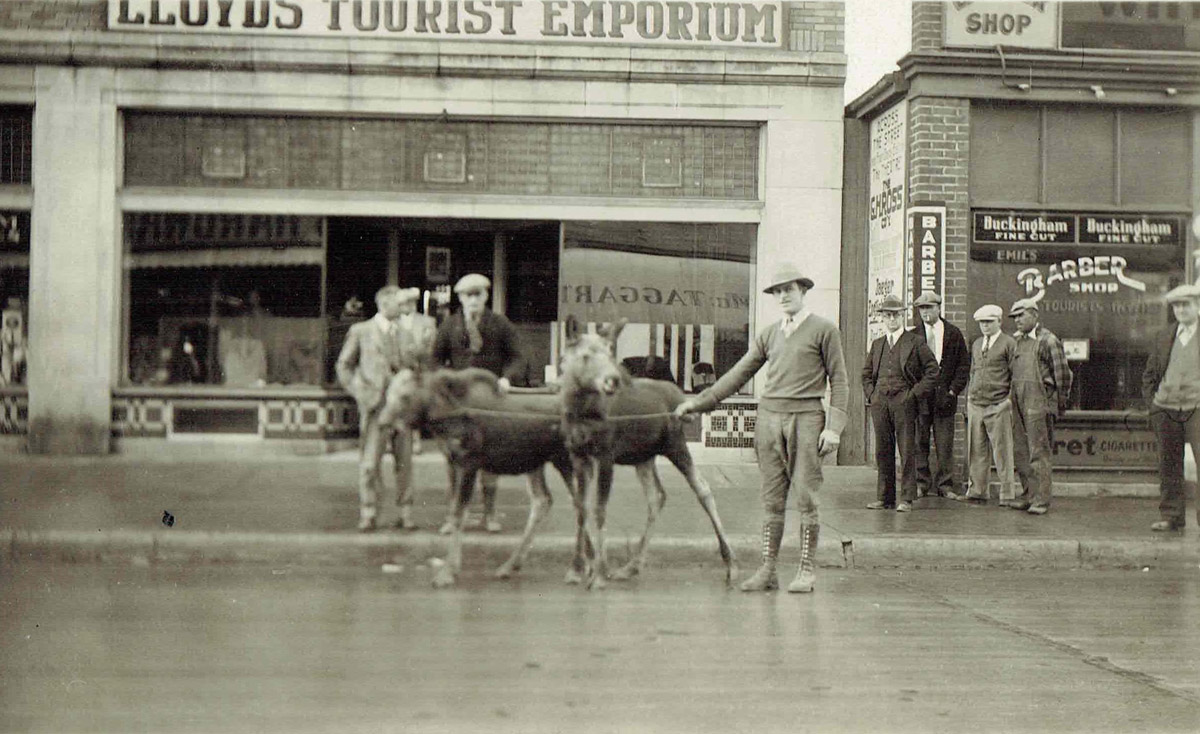

The Rainy Lake Hotel’s legacy extends beyond its architecture. It was a backdrop for the town’s colorful characters, none more memorable than Alfred M. “Spike” Struve. Spike was a jack-of-all-trades—lumberman, fur buyer, and commercial fisherman. Tales of his adventures, like the time he rode a moose across Bad Vermilion Lake, were immortalized in KD Lang’s poem The Riverman:

“He would ride the swimmin’ moose, Crossin’ Bad Vermilion Lake. If he hadn’t no excuse He just rode for ridin’s sake…”

A newspaper editorial called him a “a proper roughneck,” whose larger-than-life persona embodied the spirit of a bygone age.2

The hotel continued as a social hub for decades, hosting weddings, political meetings, and travelers. In 1985 it was given heritage designation under the Ontario Heritage Act; a nod to its role in shaping Fort Frances’s identity.

In 2005 a legal dispute led to its closing. It was abandoned and became a haunting place. When municipal officials toured the building they felt like they were walking into a time capsule: "Tables were still set for dinner and the dishwashers were still loaded with dishes and cutlery." They were spooked when they discovered that "one of the unwanted visitors to the building had placed a very accurate life-sized dummy on one of the beds."

They sadly concluded that this historic landmark was beyond saving. "The best thing you could say about it was that the basement featured a 16-inch deep swimming pool in summer and an ice surface in winter."

In 2015 the Rainy Lake Hotel was torn down. Yet the town salvaged this valuable piece of land on Scott Street by building Rainy Lake Square in its place, a place for public markets, events, performances, and art exhibitions that can be enjoyed by all the people of Fort Frances.3

10. Fort Frances At War

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1950

The Fort Frances Museum is housed in one of the oldest buildings in town, which dates back to 1898. It was first built as Scott Street School and served in that role until 1914, when a bigger school was completed to educate the growing number of children in Fort Frances.

During the First World War it was given over to the military and an encampment was set up behind the building by the 141st Bull Moose Battalion and 52nd Battalion between Scott and Church Streets.

After the war the Canadian Legion bought the building, renovating it into a hub for veterans. In the late 60s and 70s it variously served as a chamber of commerce, police station, and assessment office. Finally in 1978 it became the Fort Frances Museum, which it remains to this day. You should go inside and visit!

* * *

During the First World War, the 52nd Battalion (New Ontario) drew recruits from the Rainy River District, Fort Frances, Kenora, and Thunder Bay. From 1916 on they fought in almost all the Canadian Corps' major battles, from the bottomless mud of Passchendaele to the shattering of the Hindenburg Line.

By war's end 90% of the 1,000 original volunteers were dead, wounded or missing. Their ordeal was immortalized in From Thunder Bay to Ypres with the Fighting 52nd, a brutal chronicle by Private W.C. Millar, who wrote of "mud-choked rifles" and being haunted by the "ghostly silhouettes" of his lost comrades.1

Not all stories ended in tragedy. Lieutenant Leonard Williams, a fighter pilot from Fort Frances shot down seven German planes, and became a hometown hero. After the armistice, Williams became a mechanical engineer and took over the town's roads department.2

When the Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919, Fort Frances erupted in celebration. There was a jubilant parade, with military units, decorated floats and bands marching down Front Street, crossing the bridge to International Falls, and then returning to continue parading through Fort Frances. Virtually the whole town turned out to cheer the soldiers on.3

During the Second World War Fort Frances once again did its bit. The town raised an artillery unit, the 17th Medium Battery and 31 men from Fort Frances enlisted in the infantry with the Lake Superior Regiment in 1940. Others joined the Forestry Corps, a support unit that provided the huge quantities of wood necessary to sustain modern military operations.

As these men went overseas, people on the home front mobilized to support the war effort. Rationing of everything was quickly instituted. The Fort Frances Times reported how gas rationing limited drivers to about 300 gallons a year. The sudden disappearance of cars left Scott Street eerily quiet.4

In 1946, the end of the war brought weary soldiers home and life gradually returned to normal. Veterans returned to their old jobs at the paper mill or launched businesses along Scott Street. People were ready to move past the decades of war and economic depression and looked forward to decades of peace and prosperity.

11. Frontier Medicine

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1920s

In this photo we are looking back down Scott Street in the 1920s. The building on the corner at the right, the Baeker Block, was completed in 1925 to house G.G. Baeker's drug store. Druggists like Baeker and doctors like Dr. Hugh W. Johnston were important and well known members of the community.

Johnston in particular has a fascinating story. Starting as a pharmacist, he completed further medical training at the University of Toronto and became a doctor. Fort Frances desperately needed a doctor and in 1909 Johnston answered the call. In 1916 he paused his practice to serve as a medical officer in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. He survived the war and in 1919 returned to his role in Fort Frances.

* * *

Johnston made four to eight house calls a day. This was decades before Canada's system of universal healthcare, so he charged $1 to $2 per visit (around $25 to $50 today).

He relied on remedies like “Pepto-Mangan,” a tonic of iron and manganese marketed to “rebuild red blood cells”, restore “healthy colour of face”, and "sustain and maintain vitality" in anemic patients. He also touted the medical value of Castor Oil de Luxe, leaving these instructions:

"Put into a tumbler about two ounces of strong lemonade, using nearly half a lemon. Pour in the desired quantity of castor oil. Stir in about one-quarter teaspoonful of baking soda. It will foam to the top of the glass. Have the patient drink it while it is effervescing. Even the oiliness of the dose is not detected..."1

12. The Hot Stove Murder

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

1913

Here we see the courthouse during its construction in 1913. Fort Frances had then been chosen as the seat of a judicial district, and this courthouse would try cases from across the region. It was an indicator of the town's growing prominence.

One of the most sensational trials in Canadian history was held in this courthouse: the grisly case that became known as the Hot Stove Murder. It was a trial that shocked the conscience of the nation and left its mark on Fort Frances.

* * *

Viola Jamieson, a 49-year-old mother of nine, was a beloved and respected member of the small community. She was at home on June 10, 1944 when four young men descended on her cabin: William Schmidt, Eino Tillonen, and the brothers George and Anthony Skrypnyk. They had overheard a rumor that Viola had a fortune hidden away in her home, and they wanted it. Locking her young sons in the root cellar, they seized Mrs. Jamieson and then tore the house apart searching for the supposed fortune. When the frightened woman failed to reveal her money's hiding place, which in any event she couldn't have done because there was none, the men started burning her on the hot stove, hoping to extract a confession.

One of her young sons escaped and brought help. The attackers had fled, but they had left behind an unspeakable scene. Jamieson survived long enough to recount the ordeal at LaVerendrye Hospital, but her burns were so severe that she soon died.

Provincial Police faced a daunting task: solving a crime with no witnesses and only the faltering account the victim gave from her deathbed. The breakthrough came from an unlikely source—a jar of preserves. Constable William Parfitt employed the then-novel technique of fingerprinting, gathering extensive samples from the kitchen and sending them to Ottawa for analysis.

A manual search of criminal records identified the Skrypnyk brothers as matching the prints on the jar of preserves. The manhunt was brief and the four men were quickly found and arrested.

The trial, held in Fort Frances that September, became a national sensation. All four men were convicted, but public sentiment split. Tillonen, just 18, had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment after the jury requested mercy on account of his youth. The others were sentenced to hang in Fort Frances Jail, despite its lack of proper gallows. Authorities improvised: a hole was cut through two floors, ropes tethered to a steel bathtub, and a “high board enclosed gallows” hastily erected.1 The sentence was carried out.

The case left scars on Fort Frances and is remembered to this day. Local filmmakers Tracy Gibson and Tom Foley resurrected it in the docudrama Flowers for Viola. Filmed on a shoestring budget at a Flanders-area farm, the project grappled with the town’s conflicted legacy. “We developed respect not just for Viola’s suffering,” Gibson reflected, “but for the families of the men hanged. They endured shame long after the ropes dropped.”2

13. La Verendrye Hospital

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

This is the LaVerendrye Hospital, which opened in 1941 as a $120,000 symbol of modernity and faith on the banks of the Rainy River. Named for the 18th-century French explorer Pierre de LaVerendrye, whose expeditions had charted these waters, the hospital was proof that this remote part of Ontario could now care for its own.

* * *

By 1941 the Sisters of Charity, Grey Nuns who had arrived in the late 1800s, decided that Fort Frances needed such a modern hospital. The three-storey building you see here, with marble sills and sunlit wards, had 50 beds, an X-ray suite, and even a mortuary cooler. These were amenities that were unheard of in earlier years.

The hospital’s surgical wing had foot-pedal sinks, glass-partitioned operating rooms, and sterilizers. There was also a chapel with stained glass windows, where the Sisters prayed for the health and souls of their patients.

For workers at the booming pulp mill and families drawn by postwar prosperity, the hospital offered more than medicine—it meant security. No longer would a burst appendix or complicated birth require a perilous journey by train or boat. As one nurse later recalled, “We finally had a place where the river’s roughness didn’t dictate who lived or died.”1

14. International Incidents

Library & Archives Canada 3385777

1899

Here we see the steamer Kenora on the Rainy River in 1899. The American Stars and Stripes on the prow and Canadian Red Ensign on the stern illustrate the close ties between the two nations that shared the Rainy River.

* * *

There were also frictions. In 1910, the Commercial Club of International Falls thought it would be a good idea to annex Fort Frances to the United States. They started calling Fort Frances “North International Falls,” and sent a marshal to plant U.S. flags on Canadian soil.

The people of Fort Frances were not impressed. They dug up some old surveys that suggested the border should actually be 14 miles south of International Falls, in which case it was Canada that should be annexing International Falls. After this was pointed out the Americans promptly dropped the matter.1

The real border chaos began in 1920, when U.S. Prohibition turned the Rainy River into a liquor superhighway. The region became the arena of an ongoing game of cat and mouse between police, liquor inspectors and the smugglers. The Fort Frances Museum's chronicle recorded one instance where:

"A gang of American bootleggers made a bold attempt to get away with Canadian Liquor via a gasoline launch at the foot of Crowe Ave. Prevented from landing by the authorities on either side, the fugitives began to dump their consignment overboard. It was noted that the upper bend of the river is likely to be a favorite swimmin' hole this summer. With a number of empty cases floating in the river, no doubt a number of expert swimmers and divers would be hunting for lost treasure as soon as the water warmed up."

On another occasion…

"A daring robbery saw some 160 to 170 cases of liquor stolen from Dunsmore Island, some eight miles east of Fort Frances. Cases were transferred to a barge and the canoes and rowboats at the island as well as parts of the engine of the launch removed to prevent any chase. The provincial police as well as American authorities were alerted and the result was the perpetrators were apprehended, noting they were Americans from Rainier."2

15. The Hallett

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1940

Here at Sorting Gap Marina we see the preserved logging tug Hallett, a ship with a long and storied history in Fort Frances.

The Hallett had been a workhorse for the Ontario & Minnesota Pulp and Paper Company for almost 40 years, pulling huge floating log booms to Fort Frances's sawmills. In 1974 the aging tugboats were finally replaced by trucks. As the Rainy River Chronicle noted, “The summer before last, the mighty Hallett towed 50,000 cords of pulp logs… and then… her era ended.” Dubbed the “queen of the Fort Frances logging fleet,” she once led a motley crew of smaller tugs, barges, and floating cookhouses that kept the mills fed.

As you might have guessed, this wasn't the end of the Hallett's story. In 1987 she was restored as a tourist attraction and remains an ongoing reminder of the town's industrial past.

* * *

George Tucker, her final captain, described 12-hour shifts in icy conditions: “6 a.m. to noon, then 6 p.m. to midnight," steering through storms and sudden squalls while dragging 4,000-cord loads. The cramped quarters didn't help matters. Captain Tucker remembered "you had to have companionship because you were cooped up on that little boat—if you had a grouchy old bugger, it wouldn't be too good".1

By 1974, highways, trucking, and environmental concerns rendered the “lake drive” obsolete. The Hallett sat idle until it was moved to Point Park. Restored in 2009, it now rests at Sorting Gap Marina—a quiet reminder of Fort Frances’s logging past.2

16. The Shevlin-Clarke Mill

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

c. 1920

This is a view taken from the water looking back towards the massive Shevlin-Clarke Mill—right where you are now standing. Opened in 1911, the mill operated for 30 years, employed thousands, and became the largest pine mill in Canada.

The industrial waterfront where log booms were floated as they awaited planing—the sorting gap—has today been transformed into a marina for pleasureboats, and represents the changing face of Fort Frances.

* * *

Within a year the massive new mill was ready to open. An opening ball was attended by over 1,500, including ladies in “glorious dresses,” and men in tailcoats. The pulp mill floor was transformed into a “fairyland” of evergreens and Japanese lanterns. One Minneapolis guest marveled, “You Fort Frances people certainly know how to entertain.”

Then they got to work. Shevlin-Clarke Co. sent out parties of lumberjacks to cut stands of fine Norway and white pine, mostly to the east of Fort Frances around the rim of Rainy Lake. The logs were floated here (with help from tugs like the Hallett) and then harvested by the mill. The mill operated until 1942, when the forests had been cut down and there were not enough good timber stands left to support the mill's continued operation.

Over its operating life the mill produced some 1.6 billion feet of lumber which were primarily sold to the United States. All told some $20 million in wages were paid out, ($400 million today). At the close of the mill the vice-president David Larsen remarked on the surprisingly strong relations between the 1,500-strong labour force and management.

He told the Fort Frances Times: “The 32-year term of operations in Fort Frances is unusual for the high degree of harmony between capital and labor and it is with sincere regret of both parties that this has to terminate with the exhaustion of the timber.”

This was in stark contrast to many other sawmills across Canada, where strikes and bitter labour feuds were commonplace.

Larsen noted Shevlin-Clarke's similarly amicable relations with the town itself, saying "“At no place where the Company has had mills during the past 60 years has it enjoyed a more congenial relationship with the town than in Fort Frances.”1

17. The Lookout Tower

Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre

2009

Our last stop on this walking tour shows the more recent erection of another attraction at Sorting Gap Marina: the Lookout Tower. It is a rather unlikely symbol of progress: a repurposed Cold War-era bomber lookout tower.

* * *

It was obsolete before it was ever used. Rapid advances in radar technology in the 1950s meant the Pinetree Line was superseded by the more advanced Mid-Canada Line which was built further to the north. That line too was itself finally superseded by the Distant Early Warning Line in the high Arctic.

As for this tower, it sat abandoned in the forest, sometimes attracting curious hikers. Then in 1972 the Industrial Development Commissioner thought it would make an interesting attraction. He successfully campaigned to have the tower moved to Point Park in Fort Frances, where cranes painstakingly reassembled it section by section.

The tower’s July 1 debut drew crowds. Ontario’s Minister of Natural Resources, presided over the opening, while local forester Ron Balkwill recounted its history. During “Fun in the Sun” festivities, 1,000 visitors climbed its open-air stairs. The initial enthusiasm subsided and by mid-July, the council ordered it closed, demanding enclosed stairwells and warning signs after safety concerns arose.1

In 1975, the Museum Committee reimagined it as a tourist draw, highlighting its dual legacy as a forestry lookout and civic curiosity. Though conceived for atomic-age vigilance, it became a perch for hikers and history buffs, that is until 2009, when it was finally moved again to the Sorting Gap Marina.

Endnotes

1. Welcome to Fort Frances

1. "Welcome to Canada' Arch", Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "Travel's come long way since Voyageurs," * Alberton Centennial Times*, 5 April 1978.

3. "Pioneers endured many hardships to settle region," *Fort Frances Times, 1 January 1991.

2. Starting a Town

1. "1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "Pioneers endured many hardships to settle region," *Fort Frances Times, 1 January 1991.

3. "Butcher Shop 1904," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

3. The Emperor Hotel

1. "1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

4. The Fort Frances Hotel

1. "1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "A Papermill…A Highway. A prosperous Town and District," *Fort Frances Times,* 28 June 1965.

3. "1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

5. The Great Fire

1. "Fire department was big priority in 1903," *Fort Frances Times*, 5 April 1978.

2. "1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

6. Growing Pains

1. "1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

7. Rising from the Ashes

1. "1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

8. "Stick 'em up!"

1. "16-year-old bandit robs local bank yesterday," *Fort Frances Times*, 1 January 1931.

9. The Rainy Lake Hotel

1. "Rainy Lake Hotel," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "1940 to 1949," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

3. Peter Kenter, "Demolition of Rainy Lake Hotel gives Fort Frances a fresh start," *Daily Commercial News,* November 27, 2015.

10. Fort Frances At War

1. "Training for War, 141st Bull Moose and 52nd Battalions," Fort Frances Museum and Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*

2. "RAF Squadron," Fort Fracnes Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.a.*

3. "1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

4. "1940 to 1949," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

11. Frontier Medicine

1. "1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

12. The Hot Stove Murder

1. "Trio Paid Penalty on Gallows Today," *Fort Frances Times,* 1 March 1945.

2. Heather Latter, "Docudrama recounts 'hot stove' murder," *Fort Frances Times,* 15 October 2014.

13. La Verendrye Hospital

1. "50-Bed La Verendrye Hospital Opens It’s Doors to Public Today," *Fort Frances Times,* 5 June 1941.

14. International Incidents

1. "1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "1920 to 1929," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtel.ca*.

15. The Hallett

1. "Hallett," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

2. "1980 to 1989," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

16. The Shevlin-Clarke Mill

1. "Shevlin-Clarke Co. Ltd. Ends 32 Years of Lumbering Operations in Fort Frances," *Fort Frances Times*, 23 April 1942.

17. The Lookout Tower

1. "1970 to 1978," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

Bibliography

Kenter, Peter. "Demolition of Rainy Lake Hotel gives Fort Frances a fresh start," *Daily Commercial News,* November 27, 2015. https://canada.constructconnect.com/dcn/news/projects/2015/11/demolition-of-rainy-lake-hotel-gives-fort-frances-a-fresh-start-1011765w

**Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre Collections**

"1903 to 1909," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.histoiresdecheznous.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=search_record_detail&fl=0&lg=Francais&ex=00000558&hs=0&sy=cat&st=&ci=9&rd=134086

"1910 to 1919," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*.

"1920 to 1929," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtel.ca*. https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=record_detail&fl=0&lg=English&ex=00000558&hs=0&rd=134121

4. "1940 to 1949," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.histoiresdecheznous.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=search_record_detail&fl=0&lg=Francais&ex=00000558&hs=0&sy=cat&st=&ci=9&rd=134144

"1970 to 1978," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=record_detail&fl=0&lg=English&ex=00000558&hs=0&rd=134183

"1980 to 1989," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=record_detail&fl=0&lg=English&ex=00000558&hs=0&rd=134196

"Butcher Shop 1904," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.histoiresdecheznous.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=search_record_detail&fl=0&lg=Francais&ex=00000558&hs=0&sy=cat&st=&ci=9&rd=134088

"Hallett," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=record_detail&fl=0&lg=English&ex=00000558&hs=0&rd=134201

"RAF Squadron," Fort Fracnes Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.a.*

"Rainy Lake Hotel," Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.communitystories.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=record_detail&fl=0&lg=English&ex=00000558&hs=0&rd=134129

"Training for War, 141st Bull Moose and 52nd Battalions," Fort Frances Museum and Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*

"Welcome to Canada' Arch", Fort Frances Museum & Cultural Centre, *Museevirtuel.ca*. https://www.histoiresdecheznous.ca/v1/pm_v2.php?id=search_record_detail&fl=0&lg=Francais&ex=00000558&hs=0&sy=cat&st=&ci=9&rd=134158

**Fort Frances Times Archives**

Latter, Heather. "Docudrama recounts 'hot stove' murder," *Fort Frances Times,* 15 October 2014. https://fftimes.com/news/district-news/docudrama-recounts-hot-stove-murder/

"16-year-old bandit robs local bank yesterday," *Fort Frances Times*, 1 January 1931.

"50-Bed La Verendrye Hospital Opens It’s Doors to Public Today," *Fort Frances Times,* 5 June 1941.

"A Papermill…A Highway. A prosperous Town and District," *Fort Frances Times,* 28 June 1965. https://fftimes.com/100-years-100-stories/development/a-papermill-a-highway-a-prosperous-town-and-district/

"Fire department was big priority in 1903," *Fort Frances Times*, 5 April 1978. https://fftimes.com/100-years-100-stories/development/fire-department-was-big-priority-in-1903/

"Trio Paid Penalty on Gallows Today," *Fort Frances Times,* 1 March 1945.

"Travel's come long way since Voyageurs," * Alberton Centennial Times*, 5 April 1978. https://fftimes.com/100-years-100-stories/transportation-the-opening-of-the-west/travels-come-long-way-since-voyageurs/

"Pioneers endured many hardships to settle region," *Fort Frances Times, 1 January 1991. https://fftimes.com/100-years-100-stories/settlement/pioneers-endured-many-hardships-to-settle-region/