Walking Tour

Bullseye of the Dominion

The Boomtown Era 1870-1912

Andrew Farris

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 10-001

At the end of the 19th Century and at the start of the 20th, this city was the scene of one of the great dramas of Canadian history.

For thousands of years aboriginal peoples have followed the rhythm of the seasons, coming to this place to meet and trade. That timeless way of life, however, was about to be decisively interrupted. Forces in motion thousands of kilometres away--empire and nation building, capitalism and commerce--would bring people to the Forks, hundreds of thousands of them.

After 1870 the history of this place entered a new phase. The population of Winnipeg, as it became known, doubled, and then doubled again, and again. The 250 people who called Winnipeg home in 1870 had grown to over 150,000 by 1913. Astonished observers predicted a population of a million within a decade.

What drove this boom? Why did these people come here? Who were they?

This walking tour uses photos from those exciting times to chart that remarkable journey. Beginning at Portage and Main, where Winnipeg as we know it began, we'll continue north up Main Street through the railway booms and busts and the establishment of Winnipeg as the metropolis of the Canadian West. Finally we'll complete our journey near City Hall, and experience the wild exhilaration people felt at the peak of the boom, when anything seemed possible and Winnipeg's potential was without limit.

This project is a partnership with Heritage Winnipeg. We also owe thanks to the generous support of Travel Manitoba, the Exchange BIZ, and the Fort Garry Hotel.

1. A spot upon the moon'

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 00-181

1873

This photo of a man standing in the mud of Main Street shows Winnipeg at the outset of its journey to metropolis. The phase of its history as an isolated trading post and meeting place was drawing to a close. You can see it represented by the squat white turrets of Fort Garry in the distance in this photo.

* * *

Until the arrival of the railway, the fastest and easiest way to move around this hinterland were the rivers and tributaries that knitted the continent together. For thousands of years they had allowed traders and adventurers to venture for thousands of kilometres. At the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers, Winnipeg lies on a crucial node of that transportation network. It's no surprise that archaeologists have found evidence of aboriginal people visiting the Forks at least as long as 6,000 years ago, bringing with them trade goods from as far afield as Vancouver Island and the Gulf of Mexico.1

Metis, French, and Scottish fur traders followed in the footsteps of the aboriginal peoples and established at this strategic location the trading post of Fort Garry. In the first half of the 19th Century this small encampment became a hub of activity, the main jumping off point for those ranging deep into the North West.

Hundreds of kilometres from the nearest European settlement, an inhabitant of Fort Garry must have experienced a wondrous and crippling sense of isolation that can be difficult for the 21st Century mind to grasp. A Hudson's Bay Company clerk, writing in the 1840s, said that Fort Garry was like "an oasis in the desert… a spot upon the moon, or a solitary ship upon the ocean."2

The appeal of trade must have been strong indeed for these hardy people to choose to endure in this place, for the geography that made it so favourable also threw up obstacles. The rivers frequently flooded, submerging the region with a small lake. The winters--some of the coldest on earth--linger for months. In the summer, swarms of mosquitoes torment people and animals alike. When it rained the fine river silt congealed into a thick, slurping bog known less than affectionately as 'Red River Gumbo'.

All of these geographic features have been common to the experience of every Winnipegger, and have shaped the course of the city's story.

2. The Mushroom Patch

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 00-010

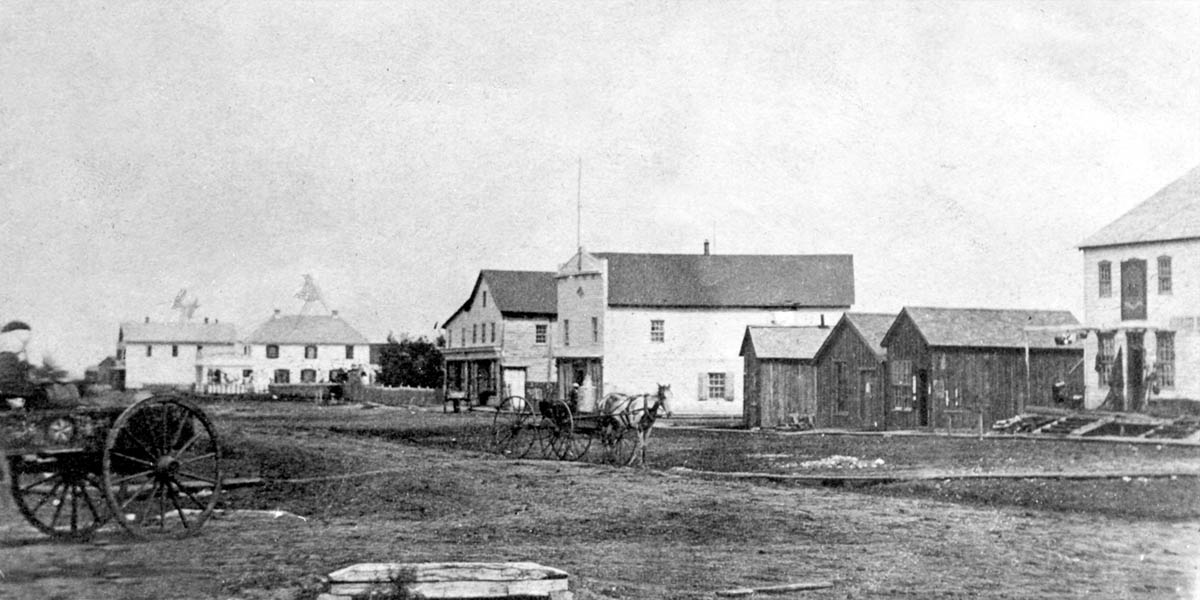

1870

A decade before this photo was taken, there were no buildings around Portage and Main. It was merely the intersection of two beaten trails that led to the Forks beside Fort Garry. When one enterprising settler decided to build a shop here in 1862, the inhabitants of the Fort thought he was a fool: The land was swampy. It was too far from the river and the fort. Yet it wasn't long before more would join him, expanding a settlement out in all directions. The seeds of the future city had been planted.

* * *

Small buildings were nestled inside long, thin plots of land. They were separated by a Main Street made extra wide to prevent the two-wheeled Red River carts from sinking into muddy ruts. Viewed from a distance the settlement appeared tiny, like a little mushroom patch. Hence its first nickname: The Mushroom Patch.

Officially it was still considered part of Fort Garry, but this was a new settlement which needed its own official name. Selkirk, Garry and Assiniboia were all considered and discarded. It was Winnipeg, the name of the lake to the north, that stuck. It came from the Cree for 'muddy water'. For settlers who must have sometimes felt as if they lived in a universe of muddy water, the name probably made sense. The name first appeared on the masthead of the town's first newspaper, the Nor'Wester, in 1866.

In 1870, when this photo was taken, the population had only reached 250. The historian Alexander Begg, reflecting on his city on the eve of its transformation, said wistfully "We had no bank, no insurance office, no lawyers, only one doctor, no city council, only one policeman, no taxes - nothing but freedom, and, though lacking several other so-called advantages of civilization, we were, to say the least of it, tolerably virtuous and unmistakably happy."1

But these quiet days were coming to a close: The wheel of history was turning. A new nation had been born in the east--Canada--and another--the United States--had just finished a Civil War and was resuming its drive to expansion. Both were turning their eyes to the North West. Both knew Winnipeg was the key to controlling it.

3. Into Canada

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 00-011

1876

To reach this stop go into the Scotiabank building behind you to access the pedestrian underpass. You can use it to cross to the northeast corner of Portage and Main.

Right now, you are looking north on Main Street, which has been graded and become much more crowded in the six years since the photo at the previous stop. The building at the end was the City Hall, which was built in such a rush that cheap materials and careless foundation laying caused it to sag and almost collapse. The rush to bring the Red River Colony into the Canadian Confederation, and the Riel Rebellion that resulted, helped spur Winnipeg's first building boom.

* * *

At that time almost all of what is now western Canada was the exclusive preserve of the Hudson's Bay Company. Their traders had been radiating out from Hudson's Bay since the 1600s, but by the mid 1800's their power was waning. In London the architects of the British Empire saw new possibilities for the vast prairies of the northwest. They also knew that if they didn't seize the initiative, the Americans would take it first.

At the time, America was in the grip of manifest destiny, an expansionist desire to spread their republic across all North America. They saw how weak Britain's grasp was west of Ontario, and believed they could draw all that land into America's orbit. A Senate committee thought if they built a railway near the border, the North West "will become so Americanized in interests and feelings, that they will be in effect severed from the New Dominion, and the question of their annexation will be but a question of time."2

In 1867 the British shepherded their colonies in North America into the Dominion of Canada, under British protection. The British and Canadians now rushed to attach the rest of the North West to Canada. In 1869 this plan appeared almost complete.

When government representatives arrived at the Red River Colony to begin the transfer of the colony to Canada, they acted arrogantly and disrespected the rights of the long-standing Metis inhabitants. This led Louis Riel to expel the representatives of the government and set up his own provisional government. The Red River Rebellion was a pivotal and at times comic series of events that mostly occurred in Fort Garry, and that the inhabitants of Winnipeg mostly sat out.

The rebellion concluded with the arrival of a Canadian military expedition, the flight of Riel, and the joining of the province of Manitoba to Canada in 1870. With this confederation came government subsidies and new settlers (including many of the soldiers) that helped cement Winnipeg's ties to Canada.

Yet Winnipeg was not firmly ensconced in Canada's orbit yet. Their primary connection to the outside world remained steamships chugging up the Red River to Minnesota in the US. If Canada wanted to keep Winnipeg--and the prairies beyond--from slipping into American hands, they would need a more drastic solution.

4. The Key to Prosperity

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 04-349

1905

This is the grain exchange building. At the time it was completed in 1907, it was the largest office building in Canada. Its raucous trading floors reverberated with the frantic shouts of traders who managed the sale of practically all Canada's grain to a hungry world. That grain, grown on the endless fields stretching to the Rockies, were key to settling the Canadian prairies and funding the railways ran through Winnipeg. The combination of grain and railway were key to the city's prosperity.

* * *

Yet railways were an incredibly expensive enterprise, and the young nation was not rich. The main prize the government could offer to the railway capitalists capable of the task was the prairie land itself.

The railway barons knew that prairie land was fertile--some of the most fertile in the world as it turned out. If they could fill those prairies with farmers, the farmers would need to use the railway to get their grain to to the great cities of the east and beyond. That was a way for them to make tremendous profits. A deal could be cut.

After bitter parliamentary debate, in 1881 the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was formed to build a railway that spanned Canada. In exchange the government granted them a staggering sum of $25 million and a grant of 100,000 square kilometre land grant.

Little thought was given to the First Nations peoples who stood in the way of the railway, and were to be cruelly swept off the lands where they'd practiced their way of life for millennia.

For Winnipeg the question remained: Where would the railway go? The CPR's engineers were reluctant to run the rails through Winnipeg, as it flooded too frequently. They wanted a drier route through Selkirk, to the south.

Winnipeg's growing class of wealthy businessmen knew that this decision would be the most fateful in the city's history: If the railway went elsewhere, so would all the immigrants, jobs and wealth. But if it went through Winnipeg, then the city would become the launchpad for one of the greatest epics of settlement and expansion in history.

They lobbied the CPR furiously, going so far as voting to pay the railway company $200,000, grant them permanent tax exempt status, and build the Louisa Bridge over the Red River for their use. The kickback worked! The railway would go through Winnipeg.1

Almost overnight the city burst into frenetic activity. Construction materials flooded into the little town: 500,000 railway ties, 6,000 telegraph poles, hundreds of kilometres of steel rails, thousands of men and horses. The railway boom was on.2

5. The First Land Frenzy

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 05-104

1873

On this spot was the Dominion Lands Office which managed the sale and distribution of public lands to homesteaders in Winnipeg. After this photo was taken in 1881, the announcement that the CPR would route through Winnipeg set off a frenzied rush to buy speculative real estate in Winnipeg and other townsites being laid out along the tracks. One plot of land sold for $15,000 one day, $20,000 the day after that, and $25,000 the day after that. Three months later it was valued at $180,000.1

* * *

"That Winnipeg is destined to be the great distributing and railway centre of the vast North West is now no empty figure of speech, for it admits of no denial, it being all but an accomplished fact. Winnipeg must advance. Ten years from now she will be ten times the size she is today. Her levees will be lined with steamboats; her river banks with elevators; industries and manufactures will spring up in her midst and the shrill whistle of the locomotive, piloting the rich burden of cereal products from the supporting west, will ring in the dawn of the creation of a wealthy and populous city, that the boldest enthusiasts until now have hardly had the audacity to contemplate."2

Winnipeg was to be the great depot and assembly area for the railway as the tracks surged west. The CPR began building its massive railyards to the north of the city, along with the workshops that would service and repair every locomotive and wagon between Vancouver and the Great Lakes. The economy surged and the financiers and capitalists in London took notice.

Canada had long been an unpopular destination for the London banks, who at this time dominated global finance. The United States and Australia had offered more lucrative returns.

Now their attitude changed, and British investors began to pour their money into land in western Canada, betting on the nation's future prosperity. Of all the foreign investment in the North West to 1882, three quarters of it was in 1881.3

There were soon dozens of realtors plying Main Street, cajoling recent arrivals to spend whatever money they had on land that they could they could sell again in a week or a month for a handsome profit.

Some of these realtors became legendarily wealthy. One of the most famous was Jim Coolican, the "Real Estate King", who claimed to take a bath in champagne whenever he made a 'killing.' A newly arrived Englishman sought to emulate him and spent $300 for a champagne bath at a hotel. The hotelkeeper shrewdly re-bottled the champagne after the man had left.4

6. Chicago of the North

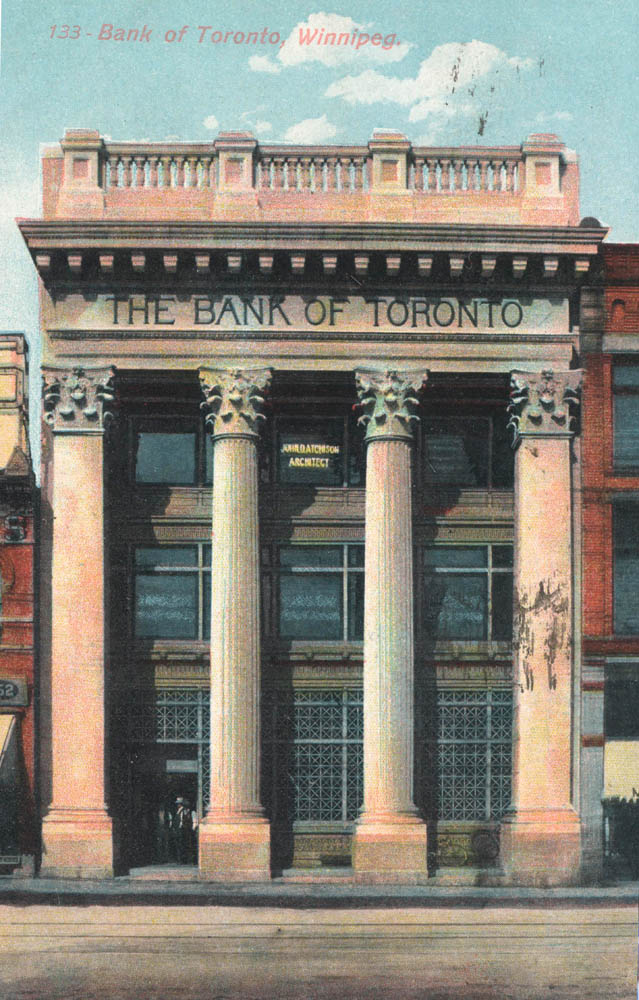

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 02-301

1903

This is a view looking across to "Newspaper Row" - at the time, home to some of Winnipeg's surprising number of newspapers. The real estate bubble popped in April 1882, leaving the young city's residents with a hangover. Yet growth recovered and continued. When the railway was completed in 1885, Winnipeg was far and away the most important city on the prairies.

Chicago had recently experienced one of the biggest population booms in history and was now one of the world's leading cities. Boosters of Winnipeg expected their city to do the same and they took to calling it the "Chicago of the North."

* * *

All the accoutrements of a modern city appeared: theatres and parks, fraternal orders and sporting clubs, streetcars and electric lights, and of course newspapers.

Winnipeg has a curious reputation in the annals of Canadian journalism: 'The graveyard of journalism.' The entrepreneurial settlers started up a dizzying array of newspapers in Winnipeg's early years. They went bankrupt just as quickly. By 1889, 21 newspapers had already been established in Winnipeg.2

Only one, the Manitoba Free Press, was still publishing at that time. Despite, or perhaps because of, the city's daunting reputation, it produced many of Canada's legendary journalists and editors. The Manitoba Free Press defied the odds and survived to the present, remaining one of Canada's foremost newspapers, becoming in 1931 the Winnipeg Free Press.

Practically everyone confidently forecast Winnipeg's meteoric rise to continue endlessly. The aim was always more people, new construction, economic expansion. This attitude was boosterism. "The essential and paramount need of the West is population." The Manitoba Free Press explained it in 1904. This was "an article of faith with every man possessed of the most elementary knowledge of the conditions and needs of the west. It permits no argument. It is an axiomatic truth."3

As the historian Pierre Berton writes "Most Westerners believed Winnipeg would soon be the largest city in Canada, outstripping both Toronto and Montreal." Anyone who disagreed was derided as a 'knocker'.

7. The City Fathers

Winnipeg Archives CA COWA C13-P00006-86

1907

The Bank of Toronto was one of so many banks that lined Main Street that the strip became known as Banker's Row. Winnipeg's newly wealthy, many of whom had come up from nothing and made their riches through their own sweat and gumption, were the city's strongest boosters. They promoted the city, straining themselves to push for as many immigrants and as much investment as could be conceived. Yet, the unrestrained capitalism of the time prioritized economic expansion at any cost.

* * *

There was little voice for the working man. Of 515 councillors between 1874 and 1915, only 3 represented labour.1 The remainder were overwhelmingly drawn from the business elite, who socialized together at the Manitoba Club and the Winnipeg Board of Trade.

The historian Alan Artibise explained their outlook:

"Measuring progress in material terms, Winnipeg's businessmen directed their efforts toward achieving rapid and sustained growth at the expense of any and all other considerations. Regarding Winnipeg as a community of moneymakers, they expressed little concern with the goal of creating a humane environment for all the city's citizens. Accordingly, habits of community life, an attention to the sharing of resources, and a willingness to care for all men, were not much in evidence in Winnipeg's struggles to become a 'great' city. Rather, the most noteworthy aspect of Winnipeg's history in this period was the systematic, organized, and expensive promotion of economic enterprise by public and private groups within the city,"2

This was the laissez-faire capitalism of the gilded age.

8. The Boomtown

Virtual Heritage Winnipeg 00-210

1910

A parade float on Main Street has been surrounded by curious children. In those heady days at the start of the last century, walking the streets of Winnipeg must have been an exhilarating experience. It was a city of contrasts, where overnight millionaires coexisted with penniless immigrants and grew by the day.

* * *

Yet the possibility of riches continued to draw people from across the world. The city continued to grow relentlessly, especially after 1896 when much of the world entered a period of unprecedented economic growth. It reached 40,000 by 1900 and had more than tripled to 150,000 by 1913, making it the third largest city in Canada.2

An active campaign by the Liberal Minister of Immigration Clifford Sifton drew immigrants from across Europe and the United States. They were Irish, Icelandic, German, Jewish, English, American, Austrian and Ukrainian. The streets were filled with the babble of a dozen languages. All these cultures and ethnicities made Winnipeg a singularly diverse city, a characteristic it has maintained to this day.

Nevertheless few provisions were made for all these new people when they arrived. "All the prairie cities were hideously overcrowded, a direct result of the city fathers' hunger for more and more people."3 In Winnipeg, most were crammed into the slums on the north side of town--'the other side of the tracks' both literally and figuratively.

The boomtown atmosphere of easy money was infectious. Hotels and drinking establishments were everywhere. There were 20 hotels on a short stretch of Main Street that all served liquor. Public drunkenness was common.4

The population skewed heavily male and young, and so the city supported dozens of brothels. The police frequently raided the brothels and shut them down, but just as soon they'd reopen somewhere else. In one embarrassing incident a police raid discovered the chief of police himself in the act of patronizing a brothel.5

If they could not shut down the brothels, polite society at least wished they'd go somewhere out of sight. Finally, in 1909, the police chief went to Winnipeg's foremost madam, Minnie Woods, "Queen of the Harlots," and proposed a compromise. Together they went and picked out a small area near the CPR tracks and the hotels that could serve as a new red light district, far from prying eyes. In a short time there were 200 prostitutes crammed in to two city blocks.6

9. Launchpad of Colonization

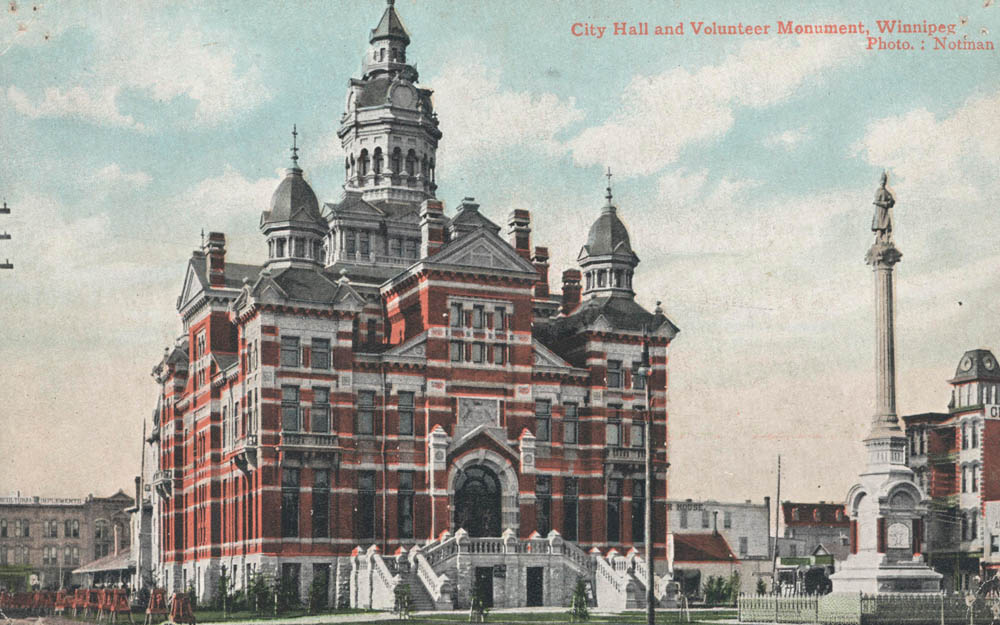

Winnipeg Archives CA COWA C13-P00001-29

1900s

After Winnipeg's first city hall threatened to collapse from poor construction, it was replaced by this 'gingerbread' city hall on the same spot in 1882. It remained a prominent Winnipeg landmark and the centre of civic life until its demolition in the 1960s.

As the essential bottleneck in a rapidly expanding rail net, Winnipeg of the early 1900s totally dominated the prairies. Calgary, Edmonton and Saskatoon all paled in comparison to the undisputed metropolis of the prairies. At the geographic and strategic centre of Canada, sloganeers took to calling Winnipeg 'the Bullseye of the Dominion.'

* * *

Happily for Winnipeg, from 1896 the global economy entered one of the strongest and most sustained periods of growth ever. Financiers in London, New York and Toronto began to pour money into Canadian railways.

By this time Canada had once again caught railway fever. A million immigrants were flowing into the prairies and a single railway couldn't service them all.2 The CPR had only survived the global recession of the early 1890s by charging sky-high freight rates and stubbornly refusing to build spur lines. Angry demands by farmers and politicians to break the CPR's monopoly, and the sudden availability of easy money, spurred the construction of three new transcontinental railways: the National Transcontinental, the Grand Trunk Pacific, and the Canadian Northern.

Winnipeg was chosen as the route of--and the workshop for--the new railways. By 1905 the building reached a fever pitch with 1,746 km of track laid. In 1912 the largest stockyards in the British Empire opened in Winnipeg.3 24 railway lines radiated out from Winnipeg in all directions.4

People and goods moved west through Winnipeg to their destinations in the prairies. In return the new farmers sent east tens of thousands of boxcars of wheat. In 1906 over 68,000 passed through Winnipeg, far more than any other city in North America. The Winnipeg Board of Trade secured privileges mandating that practically all of Canada's grain had to be handled by the city's traders. Winnipeg Grain supplanted Liverpool Grain as the international standard, much like Brent Crude or West Texas Intermediate are the standards for oil today.5

In 1911 a visiting Chicago journalist marvelled:

"All roads lead to Winnipeg. It is the focal point of three transcontinental lines of Canada, and nobody… can pass from one part of Canada to another without going through Winnipeg. It is a gateway through which all the commerce of the east and the west, and the north and the south must flow. No city, in America at least, has such absolute and complete command over the wholesale trade of so vast an area."6

10. Dizzying Heights

Winnipeg Archives CA COWA C13-P00006-84

1912

A view of City Hall with the Union Bank skyscraper completed in 1904. This was Winnipeg's first skyscraper, and is the oldest surviving skyscraper in Canada.1 Skyscrapers were a totally new building style that was pioneered in Chicago and relied on steel frames, curtain walls, and elevators. The 12 skyscrapers built in Winnipeg between 1900 and 1916 were the architectural marvels of their age and symbolized the wealth, modernity and optimism of the city's inhabitants.2 Winnipeg's explosive growth and another real estate bubble continued through 1912, the dizzying peak of Winnipeg's boomtown era.

* * *

Construction began on a great aqueduct to bring fresh water from a reservoir 140 km away into the city. The Winnipeg Electric Company's hydroelectric dams provided Winnipeggers with the cheapest electricity on the continent.4 Much of that electricity was used to power Winnipeg's factories that produced equipment and goods of all kinds for the settlers in the hinterland. Winnipeg's manufacturing capacity soon rose to challenge that of Toronto and Hamilton.

Winnipeg was not the only place experiencing good times. After Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces in 1905 their cities grew twice as fast as Winnipeg, though they were all starting from scratch and had a long ways to go to catch up.5

Towns like Calgary, Edmonton and Saskatoon all experienced their own crazed real estate bubbles. A lot sold in Calgary for $2,000 in 1905 was fetching 150 times that in 1912. In Edmonton properties sometimes flipped three times in three hours.

Winnipeg real estate firms were often the ones doing the property flipping. Many realtors would pay squatters to stake out the best lots on empty plots of land by the railway so that the land could be snapped up as soon as it came on the market. An empty field that was to one day be known as Calgary was filled with squatters awaiting the arrival of the railway.They bought land along dozens of railway sidings and subdivided them into planned towns that existed only on paper. Full page ads in Winnipeg papers flattered, shamed and cajoled anyone and everyone to invest in speculative real estate.

The worrying similarities with the 1882 real estate bubble—which bankrupted 75% of businesses in Winnipeg—were apparently lost on everyone.7

Everyone was caught up in the mania in 1912, and those few who saw storm clouds forming on the horizon were dismissed as 'knockers.' Yet the heady peak had indeed been reached, never to be reattained. For the young city, the boomtown era was drawing to a close, and a new phase of its history, a time of upheaval and conflict, was about to begin.

Endnotes

1. A spot upon the moon'

1. Christopher Dafoe, Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent. (Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998), 11.

2. Dafoe, 12.

2. The Mushroom Patch

1. Dafoe, 49.

3. Into Canada

1. Pierre Berton. The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871, 1881. (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 2001), 15.

2. Ruben Bellan. Winnipeg's First Century: An Economic History. (Toronto: Queenston House Publishing, 1978), 14.

4. The Key to Prosperity

1. Bellan, 22.

2. Berton, The National Dream, 140

5. The First Land Frenzy

1. Bellan, 26.

2. Dafoe, 69.

3. Bellan, 28.

4. Bellan, 29.

6. Chicago of the North

1. Dafoe, 91.

2. Dafoe, 92.

3. Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984), 289.

4. Berton, The Promised Land, 290.

7. The City Fathers

1. Berton, Settling the West, 299.

2. Alan Artibise. Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth 1874-1916. Montreal: McGill-Queen University Press, 1975), 23.

8. The Boomtown

1. Berton, Settling the West, 326.

2. Dafoe, 91.

3. Berton, Settling the West, 294.

4. Berton, Settling the West, 295.

5. Dafoe, 74.

6. Berton, Settling the West, 296.

9. Launchpad of Colonization

1. Bellan, 57.

2. Berton, Settling the West, 1.

3. Bellan, 98.

4. Berton, Settling the West, 321.

5. Bellan, 71.

6. Bellan, 108.

10. Dizzying Heights

1. M. Peterson & R. Sweeney. Winnipeg Landmarks. (Winnipeg: Watson Dwyer Publishing, 1995), 47.

2. Peterson and Sweeney, 47.

3. Berton, Settling the West, 325.

4. Dafoe, 92.

5. Bellan, 110.

6. Berton, Settling the West, 341.

7. Berton, Settling the West, 339.

Bibliography

Artibise, Alan. Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth 1874-1916. Montreal: McGill-Queen University Press, 1975.

Berton, Pierre. The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871, 1881. Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 2001.

Bellan, Ruben. Winnipeg's First Century: An Economic History. Toronto: Queenston House Publishing, 1978.

Berton, Pierre. The Promised Land: Settling the West 1896-1914. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1984.

Dafoe, Christopher. Winnipeg: Heart of the Continent. Winnipeg: Great Plains Publications, 1998.

Peterson, M. & Sweeney, R. Winnipeg Landmarks. Winnipeg: Watson Dwyer Publishing, 1995.