Originally located primarily on the shore of Okanagan Lake, the town of Summerland first began to be settled in the 1890s, when the land first opened to preemption by white settlers. For millennia, the region has been home to the Syilx Okanagan First Nations, who first had contact with Europeans in 1811, when fur traders passed through the Okanagan. The Syilx took part in the fur trade through the trading of horses for European goods. Eventually, the fur trade faded away and more permanent European settlement took place in the South Okanagan, as cattle ranchers and orchardists moved to the area. Summerland's first post office opened in 1902, and the town developed rapidly from then on, aided by the investment of the Summerland Development Company, owned and operated by men such as Canadian Pacific Railway president Thomas Shaughnessy and real estate developer J.M. Robinson. Throughout the early twentieth century, the town underwent a gradual shift away from the water to a new townsite. Today, the community's main street is located two kilometres from the water, though the waterfront remains a popular part of the town.

This project was made possible through a partnership with Visit South Okanagan and Visit Summerland.

We respectfully acknowledge that Summerland is within the ancestral, traditional, and unceded territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation.

Explore

Summerland

Stories

Summerland's Early Days

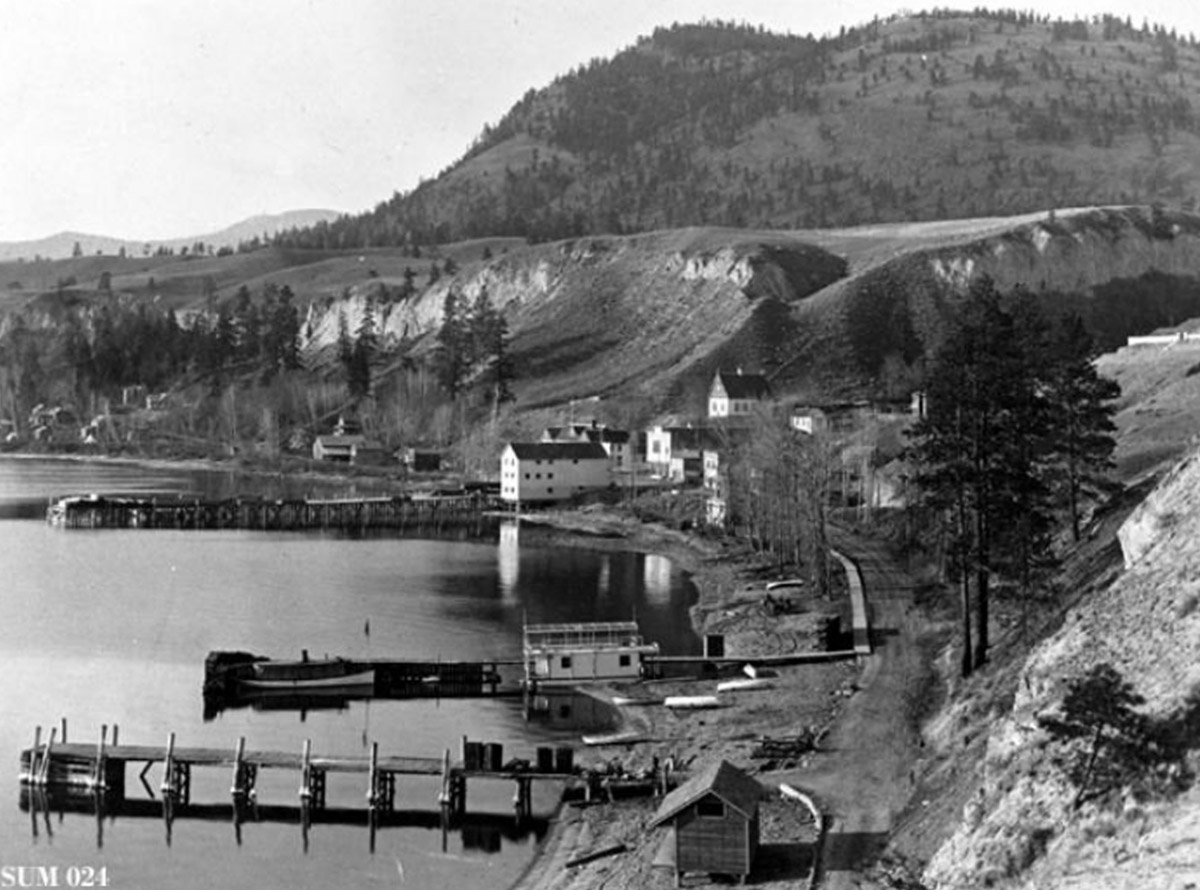

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 024

Story Location

Before the town of Summerland existed, the local Syilx Okanagan First Nations people lived here for thousands of years, living sustainably off of the land and developing complex trade routes within their own nation and beyond.

The first Europeans in the area were fur traders passing through the region in 1811. From then on, the European presence grew at a gradual yet increasingly disruptive pace. In fact, local First Nations people were affected by Europeans long before the first fur trader came to the area—smallpox epidemics swept through the area in 1775 and 1781, brought to the region through Indigenous trade routes.1

* * *

Throughout the era of the fur trade, the Okanagan people traded in horses with the European traders and occasionally worked as horse wranglers. After the fur trade declined, European cattle ranchers began moving into the area. The land on which Summerland now sits, stretching between Trout Creek and Trepanier Creek, was reserved from preemption to be used instead as common pasturage for both the animals of white settlers and the local Indigenous people.

During the beginning of European settlement in the South Okanagan, much of the land in the valley became the property of just a handful of rich white cattle ranchers. Tom Ellis, for instance, owned a shocking 30,000 acres of land in the region, stretching from the area of Penticton, where he lived, to the international border in the south. This meant that for new farmers moving to the region, land options were scarce.

These new settlers began eyeing the reserved pasture lands which sat between the Trout and Trepanier creeks. In the late 1880s, they petitioned the BC government to open the lands for preemptions—but, crucially, not for sales. This would prevent Ellis from simply swooping in and buying these lands before the new farmers could get a chance to acquire them. The BC government consented and officially opened the land for preemption in January of 1889.2

The settlement of the area of Summerland began now in earnest, despite the fact that no treaties had been made with local First Nations people. White settlers could gain title to up to 320 acres of land simply by building a house on it and living there for half of every year for three years. The land allowed to the Okanagan First Nations people was far less, even though they had been living there for millenia.

The new settler community first got the name Summerland in 1902, when the post office opened. The first Summerland townsite, which was located along the shores of the Okanagan Lake, took shape shortly afterwards, developed by the Summerland Development Company, which formed in 1903 and was headed by the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), Thomas Shaughnessy. Real estate developer J. M. Robinson, who had previously founded Peachland and would go on to create Naramata, was also a major part of the development company.

These men targeted an audience of aristocratic Englishmen and wealthy landowners from the prairies in their land advertisements. Recruitment of farmers from the prairies was particularly effective, as this quote from one of Robinson's salesmen demonstrates:

"It was a cinch selling to those farmers. You called on a prospect and if there was a young blizzard blowing, all the better. You told them that the people of Peachland at that very moment were likely swinging in their hammocks, trying to make up their minds whether to have peaches or apricots with their next meal. Then you opened up your map and accidentally dropped a few snaps of Okanagan Valley scenes on the floor…. Throw away your fur coat and live in the California of Canada!"3

With the success of these land advertisements and the funding of the wealthy men of the Summerland Development Company, the town of Summerland was quickly established. It was the first community in the Okanagan Valley to have electricity, in 1905, and, two years later, the first to have telephone service. It even had a college—the first classes at Summerland's Okanagan Baptist College took place in 1906 in rented premises. Unfortunately, the school lasted only until 1915, due to declining enrollments and the school's quickly accumulating debt.4

Summerland underwent a shift away from the waterfront throughout the beginning decades of its existence. While the main townsite was initially located on the shores of the lake, a separate townsite was subdivided in 1907 near the base of Giant's Head, at first called "West Summerland." Slowly, businesses and settlers moved to this townsite, away from the waterfront.

This move was accelerated in 1922 when a fire broke out in the frame packinghouse of the Summerland Fruit Union in the lower town. The flames destroyed many businesses in the area, including the CPR wharf and office. The following winter, another fire burned through a second section of the waterfront. Businesses began to reestablish themselves in West Summerland, and this new townsite gradually lost the "west" part of its name. The new town of Summerland was firmly established.

2. Andrew, Frederick William. The Story of Summerland. The Penticton Herald, Penticton, 1945, pp. 2.

3. Andrew, Frederick William. 9.

4. Webber, Jean. 75.

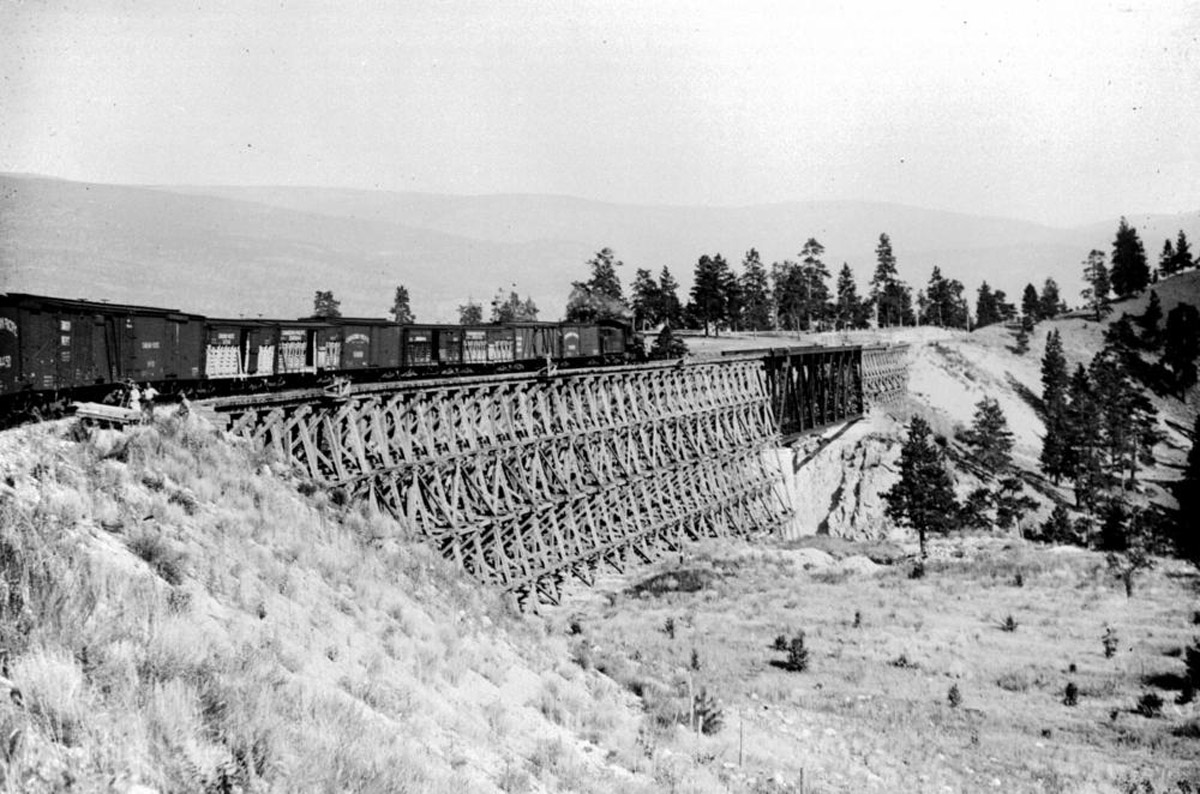

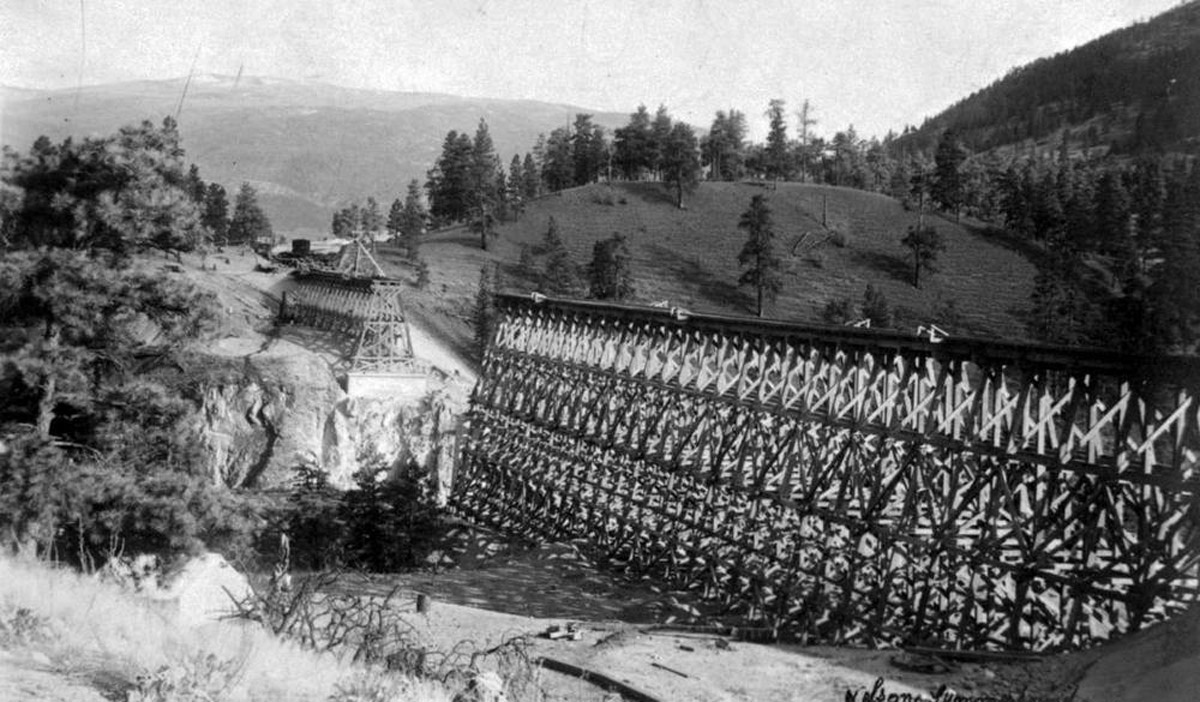

The Coming of the Railway

Story Location

In the beginning of European settlement in the South Okanagan, transportation was difficult and time consuming, limited to either long journeys by horse and foot or infrequent boats across the waters of the lake. While semi-regular steamship service was first launched in the Okanagan Lake in 1893 with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) vessel the SS Aberdeen, rail transportation was a much more complicated issue.

* * *

When the Canadian Pacific Railway was first constructed across the country in the 1880s, the route chosen through British Columbia was farther north than the Okanagan, and for good reason—three treacherous mountain ranges blocked the way between the Okanagan and the west coast. Building a railway over these mountains was thought to be all but impossible.

Yet the desire for such a railway persisted, and for decades, railway companies fought heated battles for access to the wealthy mines of the Kootenays and Boundary Country near the Okanagan. The CPR's greatest railway rival was the American company the Great Northern Railway. The nationality of this company complicated the struggle and it became a patriotic issue: would an American company be allowed to funnel Canadian wealth to the south, or would the capital somehow be found to build an enormously expensive and nearly impossible-to-build all-Canadian railway to the coast?

CPR President Willian Van Horne made his views on the matter clear when he said he wanted the CPR to be "strong enough to mop the floor with... any other American company extending its lines into the Northwest."1

This was easier said than done. Because of the mountains which blocked the potential railway's path, it was far easier to construct a line from the Okanagan to the south than it was to construct one from the Okanagan to the west. Yet in 1910, construction on this rail line, the Kettle Valley Railway (KVR), began under the direction of chief engineer Andrew McCulloch, with funding from the CPR.

It took six years to build, and the difficulty of the construction gave the railway the nickname "McCulloch's Wonder." Treacherous canyons, narrow mountain paths, and extreme winter weather all stood in the way of its completion. The railway was built almost entirely with the labour of immigrants, particularly Chinese workers who were paid very little. The work was dangerous and exhausting, and around 100 workers died during construction.2

For Summerland, the coming of the railway was a near-run thing—the route nearly skipped the town completely. Because of the deep Trout Creek Canyon, the original surveys for the railway bypassed the town, instead remaining on the south side of the creek. In response, the community raised an uproar. The town's reeve, James Ritchie, wrote an outraged letter to the Minister of Railways in Ottawa, and in response, a public hearing was held in West Summerland, with the minister himself attending.

No official orders were given after both sides had stated their cases, but the minister made an informal request to engineer McCulloch, asking him to reconsider the initial surveys and build a bridge across Trout Creek. In the end, McCulloch agreed to comply, in the interest of both public goodwill and potential trade revenue. The Trout Creek Trestle was built.

The bridge was an engineering marvel even in comparison with the rest of the Kettle Valley Railway. When it was built, the Trout Creek Trestle was the highest trestle on the KVR, and the third largest railway bridge in all of North America. It crossed the canyon 238 feet above the creek and stretched over 600 feet long.3

Today, the trestle still exists (though in an updated and reinforced version) as part of the only remaining section of the KVR which is still in operation. A 16-kilometre section of KVR track near Summerland is still traversed by a restored 1912 steam train, run by the Kettle Valley Steam Railway Society. The society works to preserve this important piece of Okanagan history.

2. Sanford, Barrie. 10.

3. "About Us: A Brief History." Kettle Valley Steam Railway. Accessed on April 12, 2021. URL: https://www.kettlevalleyrail.org/about/.

The Science of Agriculture

Story Location

In the South Okanagan, agriculture has always been key to settlement. The first Europeans who settled here on a long-term basis were ranchers who raised hundreds of head of cattle on their vast land holdings. These gradually gave way to orchardists, who came from all over the world to grow fruit in the warm climate of the Okanagan. Fruit trees spread across the land, and each town was home to several packing houses to prepare crops for sale.

Yet as prosperous as fruit growing is in the South Okanagan, it also comes with immense challenges, and at no time was this more true than at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, when fruit growing was first beginning in the valley. Winter temperatures froze the region, codling moths destroyed crops during an epidemic in 1925, irrigation systems were difficult to build and maintain, and both equipment and knowledge was minimal.1

Advancements in agronomy made at the Dominion Experimental Farm would be required to jumpstart the Okanagan agricultural powerhouse.

* * *

Many of the settlers moving to the region had no idea what they were getting themselves into. Land developers targeted prairie communities with their sales, painting a picture of fruit growing as easy and profitable. As one early pioneer said:

"I came to the Okanagan Valley with the idea, common to many travelers from the Prairies, that growing fruit-bearing trees is easy. You plant the tree, wait until the crop is ready, then harvest the perfect, abundant fruit. As I became involved in orcharding, I realized that nothing could be further from the truth; in fact, it is an extremely complicated endeavor and its complexity increases with time."2

In response to all of these difficulties, the federal government created an experimental research farm in Summerland in 1914. The Summerland Research Station, then called the Dominion Experimental Farm, was put under the management of a successful farmer in the area, R.H. Helmer, who became the farm's superintendent. The goal of the farm was to provide scientific knowledge to the region's struggling farmers and find solutions to problems such as disease, pests, and the difficulties of fruit processing.

In the following years, the new farm slowly established itself. The land was cleared and an irrigation system was built to water the crops. In the first year, the main crop was beans, though other crops such as grass, hay, and potatoes were also planted. Later, this list would expand, and the focus would be placed on fruit growing.

Yet the experimental farm faced all of the challenges of other farms in the area, and the initial years of its operations were fraught with difficulties. During the late 1910s, the farm struggled with water shortages, as their water would be cut off without notice whenever the water was needed by an orchard in the area instead. Irrigation methods gradually improved during the 1920s with installations of diesel water pumps, yet as one historian says of those early years, "except for keeping the orchards alive, little was accomplished horticulturally."3

Eventually, however, more progress began to be made. In 1921, the Laboratory of Plant Pathology was established in response to an outbreak of fire blight, and in 1929, the Department of Food Processing was opened to deal with issues concerning shipping and storing fruit. In fact, the process of creating commercial fruit leathers, which are now popular across North America, was developed through this department.4

In addition to this research, the farm continued to plant a wide variety of crops in order to figure out which could be successfully grown in the Okanagan, including crops such as hemp and tobacco. Experiments were run to determine the usefulness of various pesticides and fertilizers, the effect of different soil types, and the importance of crop rotation. Research was also conducted into pollination and beekeeping, among other things, and the farm kept and studied livestock such as cattle, chicken and sheep. As early as 1928, the research facility was studying grape varieties to see which would grow best in the area, though the vineyard industry did not take off in the Okanagan until decades later.

Today, the Summerland Research Station is still devoted to studying agriculture in the region, though its focus has narrowed to the fruit and grape crops now grown widely in the South Okanagan. The 320-hectare site includes 90 hectares planted with fruit trees and grape vines, along with greenhouses, an isolated "virus orchard", and food research laboratories. Current research focuses on studying the agriculture industry's capacity to resist climate change.

2. Fleming, W. W. Summerland Research Station: 1914-1985. Research Branch, Agriculture Canada, 1986, pp 8.

3. Fleming. W. W. 16.

4. "Summerland: A Brief History." Summerland Museum. URL: https://www.summerlandmuseum.org/summerland-a-brief-history

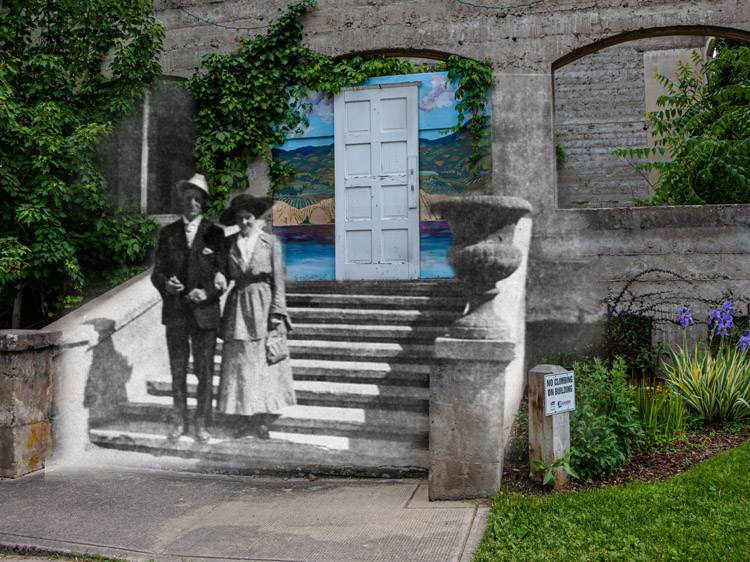

Then and Now Photos

A View of Summerland's Waterfront

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 065

1910

This photograph from 1910 was taken from Solly Road and looks down over the original Summerland townsite beside the waterfront. The white house on the right side of the image belonged to J.M. Robinson, a key real estate developer in the town. Also visible is the church, in the center of the image, and the Canadian Pacific Railway wharf to the left.

Rosedale Road

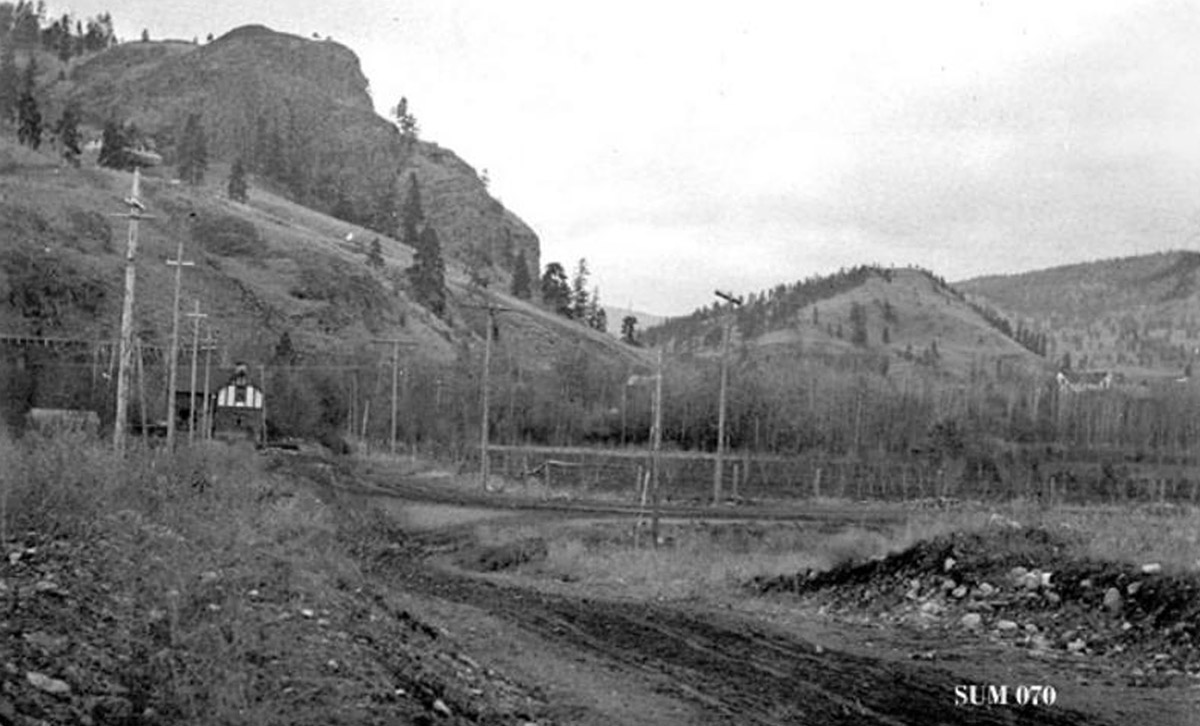

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 070

1910

This photograph from 1910 looks southeast down Rosedale Road towards Giants Head. The street is brand new, still more of a mud track than a road.

Main at Victoria

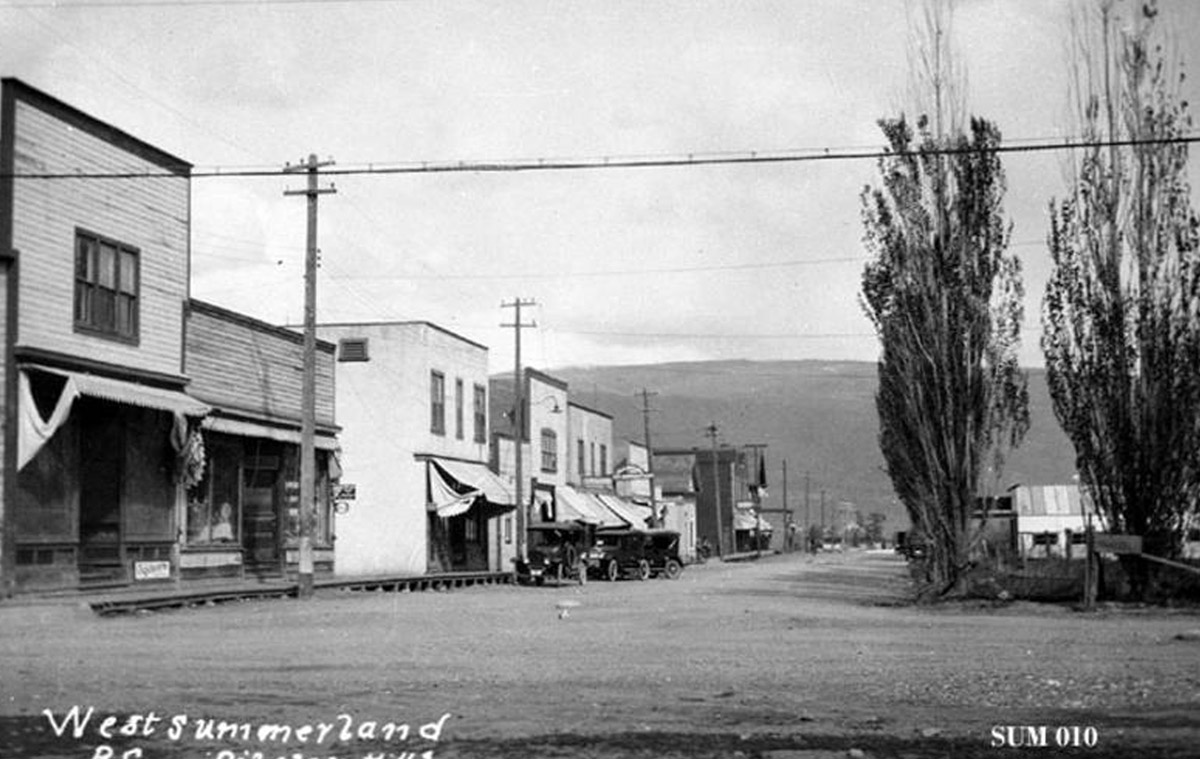

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 010

1930

The building on the left side of this photograph of Main Street and Victoria Street still remains standing. The road remains unpaved in this photo, but horses have been replaced by early automobiles.

A Vista Over The Lake Shore

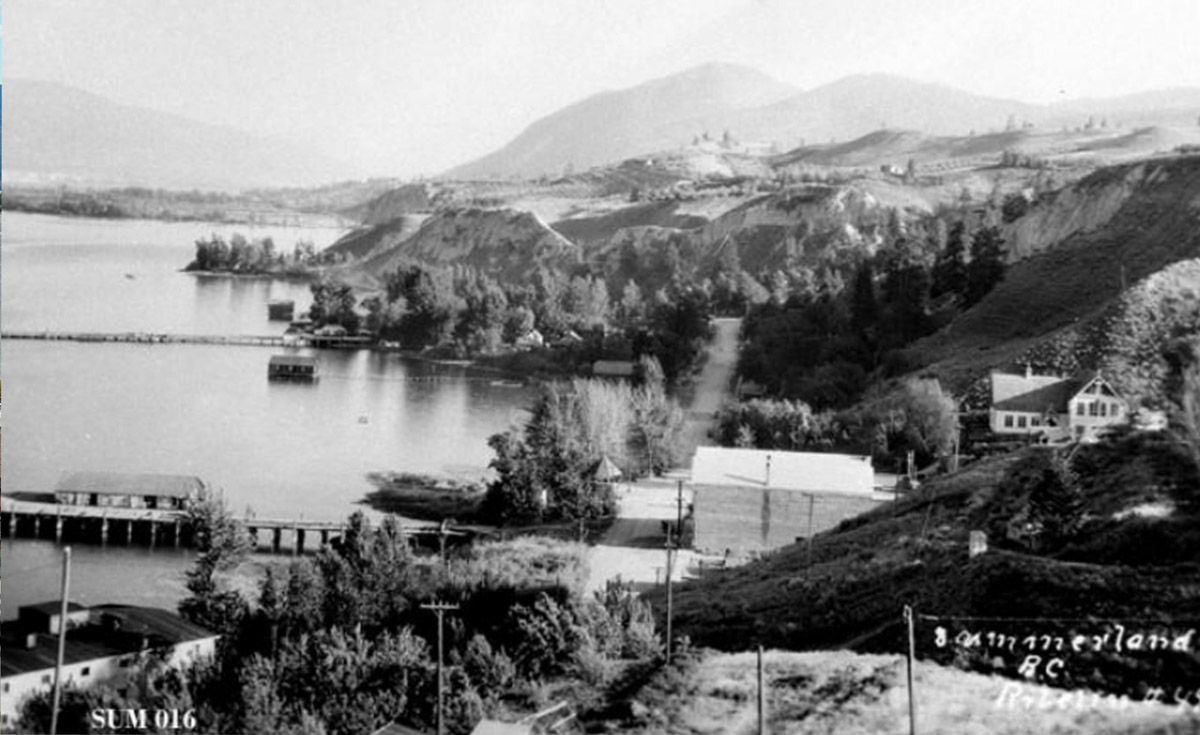

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 016

1930

This photograph from 1930 shows Summerland's lower town clearly. The CPR wharf is to the left, along with a corner of the fruit packing house. Lakeshore Drive is straight ahead, quiet and without cars after the townsite shifted away from the lake to the west during the 1920s.

A Red Cross Event

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 075

1942

In this photograph from 1942, a group of kids march in uniform across the school yard as part of a Red Cross event during the Second World War. The church is visible in this photograph in the background at center left.

A War Time Rally

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 078

1942

This war time rally took place in 1942, during the Second World War. In this photo, the children of the school are gathered in a large crowd on the school grounds with their parents standing on either side. The packing house is in the background of the photo.

Construction of the School

Okanagan Archive Trust Society SUM 026

1951

This high school was constructed in 1951, the year this photograph was taken. Previously, high school had taken place in a small four-room schoolhouse, but a growing population necessitated the construction of this new building.