Located in the sunshiney South Okanagan between Okanagan Lake and Skaha Lake, the city of Penticton is one of the only cities in the world to be nestled between two lakes. The area has been home to the Syilx Okanagan First Nations for millenia. The first European to settle in the area was Tom Ellis, an Irish immigrant who preempted land here in 1866 and went on to become known as the "Cattle King of the Okanagan". When Ellis eventually sold his land in 1892 and retired from ranching, developers laid out a small townsite on the shores of Okanagan Lake. Penticton was incorporated as a town in 1908, and soon grew into a thriving community with the arrival of the Kettle Valley Railway, the headquarters of which were located here. Today, the city is known for its orchards and vineyards, its event culture, and its long sandy beaches.

This project was made possible through a partnership with Visit South Okanagan, with support from Travel Penticton and the City of Penticton. We also thank the Penticton Lakeside Resort Hotel & Conference Centre for their support.

We respectfully acknowledge that Penticton is within the ancestral, traditional, and unceded territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation.

Explore

Penticton

Stories

By Waves and Rails

Story Location

Like many Canadian towns, Penticton's early growth and prosperity was largely due to transportation. Yet unlike the many railway towns of Alberta, Penticton's role as a transportation hub included travel over the waves as well as the rails. In the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, transportation in the South Okanagan revolved around the lakes, which provided easy, reliable access to communities throughout the region. As such, Penticton's wharves, located at the far south end of the Okanagan Lake, became a place of bustle and business.

* * *

The first commercial boats to ply the waters of Okanagan Lake began service long before Penticton had been officially incorporated as a town. One of the first was a rowboat, the Ruth Shorts, captained by Thomas D. Shorts and used to haul freight across the lake. It first launched in 1883, and was a sign of things to come. Captain Shorts went on to launch the first steamboat on the lake three years later, the Mary Victoria Greenhow.

But it was not until the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) became involved that transportation really took off across the region, and Penticton's role as a transportation hub truly began. In 1892, a rail line built by the Shuswap & Okanagan Railway reached Okanagan Landing, at the north end of the lake. This line stretched to the CPR's main line at Sicamous, connecting the northern part of the Okanagan to the wider world via rail. All that was needed to breach the gap between the northern and southern parts of the region was a boat, and in 1892, CPR president William Van Horne announced that the Okanagan would get one.

The first CPR vessel to take to the waters of the Okanagan Lake was the SS Aberdeen, which ran between Okanagan Landing in the north and Penticton in the south. As one historian said, this new service transformed the region: "It was just as if the CPR had opened a branch line extending all the way from Okanagan Landing to Penticton. People living in communities down the valley had direct, reliable, comfortable access to the CPR main line."1

The popularity of the Aberdeen increased as farming and mining grew in the South Okanagan towards the end of the nineteenth century, and the service gradually expanded. Soon, the Aberdeen was making three return trips each week between Okanagan Landing and Penticton. The SS Okanagan was added to the route in 1907, allowing for daily steamer trips.

Then, in 1910, two years after Penticton was incorporated as a town of 600, transportation in the South Okanagan changed forever with the beginning of construction on the CPR-funded Kettle Valley Railway (KVR). On June 21, 1910, railway officials met with locals in Penticton, and an agreement was made to make the town the railway's headquarters.2 Penticton's destiny as a transportation hub was confirmed; the wharves and railway station on the shores of the Okanagan Lake would become the economic drivers of the town, propelling its growth and prosperity.

By 1914, the railway line between Penticton and Midway had been completed, and that same year, a brand new steamboat launched at Penticton: the SS Sicamous. The Sicamous was larger and more luxurious than the boats that had come before it, with amenities such as electricity and hot running water, which many of the local homesteads did not yet have. Travelling aboard the Sicamous was more of an experience than a simple act of transportation. The food cooked aboard was luxurious, the furnishings were rich and elegant, and passengers could even have hot baths for the small fee of 50 cents.3

As one passenger, Mary Orr, said when recalling the steamship, "...the SS Sicamous provided a stateliness, a dignity, a peacefulness, a nobility, to our lives that many of us will never forget."4

This stately steamship was only one part of a transportation system whose core was located in Penticton. Passengers on their way to the other communities in the South Okanagan would often stay overnight at the CPR's Penticton hotel, the Incola, which was located at the base of Martin Street beside the lake and the railway station. The location of this luxury hotel made a stop-over in Penticton an easy and enjoyable part of a passenger's journey through the Okanagan.5

The completion of the KVR in 1916 was another major milestone. Not only did the railway bring travellers and valuable freight through the town, but it also brought workers and supplies to Penticton throughout the six years of its construction. Penticton's railway station was the busiest station on the KVR, constantly thronged with travellers, businessmen, and workers. Okanagan fruit and other agricultural products flowed steadily through the town on its way to wider markets in the rest of Canada, and the region's mail travelled on the railway line and the steamships.

Yet this transportation system, so integral in the development of the region, was also relatively short lived. In 1936, the SS Sicamous was taken out of service, after years of struggling to make any profit. A combination of factors caused the end of steamship service on the lake. For one, highway construction and the rise of the automobile made the ships and trains obsolete. The Great Depression also hit the industry hard, as fewer people were travelling and fewer goods rushing off to market.

Penticton's waterfront grew quieter. The railway station declined in importance throughout the years, and the last train ran on the KVR in 1964. Highways became the main method of transportation, and cars zipped through the Okanagan far faster—though perhaps with far less elegance—than the steamships.

Yet in the South Okanagan, this important history was not allowed to slowly rot away. While the SS Sicamous did spend over a decade bobbing, abandoned, in the waters near Okanagan Landing, it was eventually brought home to Penticton in 1949 when the CPR sold it to the City of Penticton for the grand total of $1. The Penticton Gyro Club took over the ship, and for decades the Sicamous was used as a community gathering place and space for restaurants and businesses on the shores of the Okanagan Lake.

In 1988, the SS Sicamous Restoration Society was formed to save the steamship from decay and graffiti. The restaurants and businesses were evicted, the upper deck was restored, and, after thousands of hours of restoration work, the vessel was reopened as a community centre and heritage space. Today, it remains a landmark on the shores of Okanagan Lake, telling the stories of the early days of transportation in the South Okanagan.

In a similar storyline, the Kettle Valley Railway was transformed from a railway line into a world-class biking and hiking path, drawing tourists and outdoor enthusiasts to the Okanagan from around the world. These important historical landmarks remain crucial and celebrated parts of Penticton and the wider community of the South Okanagan.

2. Sanford, Barrie. McCulloch's Wonder: The Story of the Kettle Valley Railway. White Cap Books, North Vancouver, 2002, pp 128.

3. "A History of the SS Sicamous Stern Wheeler." S.S. Sicamous. Accessed on April 12, 2021. URL: http://sssicamous.ca/history-of-the-sicamous/.

4. Turner, Robert D. 39.

5. "Penticton and the KVR." S.S. Sicamous. Accessed on May 21, 2021. URL: https://sssicamous.ca/kvr/.

From Fruit to Wine: An Evolution

Story Location

Today, the South Okanagan is known for its dozens of wineries, vineyards, and orchards. Many of its hillsides are covered with orderly lines of fruit trees and trellises interwoven with grape vines. Travellers from around the world come to enjoy wine tours and fresh cherries from roadside stands. But how did the Okanagan, with its desert-like ecosystems and grassy ranges covered in cactus, become the largest producer of fruit and wine in Canada?

* * *

Since the first arrival of European settlers in the Okanagan, they have been farming. They didn't begin with grapes or fruit, but cattle. Around Penticton, Irish settler Tom Ellis preempted land in 1866 and established a successful cattle ranch that would one day earn him the title "Cattle King of the Okanagan Valley."1 By 1888, he was the largest landholder in the South Okanagan, his holdings amounting to some 31,000 acres. Ellis also became one of the first white settlers in Penticton, along with the first storekeeper, postmaster, and magistrate in the area.

The transition from cattle ranches to orchards was gradual. The first orchard in the region was planted just south of the international border, near Osoyoos, in 1857, by Hiram F. Smith, who imported over 1,000 fruit trees. Up by Penticton, Ellis planted his first apple trees in 1869, but they remained for many years a small side crop as he focused on his cattle ranch.

In the following decades, others beside Ellis entered the industry. In 1905, the Ellis family retired to Victoria, selling most of their land to the Shatford Brothers for the tidy sum of $405,000. The brothers went on to form the South Okanagan Land Company.

The Shatfords transformed some of this land into orchards, hiring Chinese immigrants to clear the land of timber and paying them rates far lower than they would have had to pay white workers. This hiring decision angered white settlers and caused them to form a mob thirty men strong to drive the Chinese workers out of Penticton. Five of the white leaders of this mob were later convicted of intimidation and fined $25 each or imprisonment in Kamloops for one month.2 Work on the orchard continued.

Despite these labour disputes, orchards continued to spread across the region. Yet it was a difficult business to succeed in. D.V. Fisher of the Dominion Research Station in Summerland described the challenges faced by early settlers in this industry:

"Great hardships were endured by the pioneer orchardists because of totally inadequate irrigation systems, recurrent winter freezes, the planting of numerous and unsuited varieties, minor element deficiencies, the invasion of codling moth which became an epidemic in 1925, and above all, by repeated failures to establish a sound marketing system backed by unified grower support."3

Due to these challenges, fruit farming did not develop into a sustainable business in the Okanagan until the 1930s, when improved irrigation systems, increased knowledge, and new technology made the industry more viable. In the 1930s, the biggest difficulty faced by orchardists remained getting their goods to market: Transportation and packing was complicated and expensive, and farmers produced more fruit than the people of the Okanagan could possibly consume.

These challenges were eased in 1939 with the formation of the BC Fruit Growers Association. It established central selling and became the sole marketing agency for the industry within BC's interior. This centralized selling organization replaced 37 agencies that had previously handled the job.4 Previously, the various agencies had driven fruit prices down as they competed for the market. With the centralized system in place, prices could be set by the growers themselves, and the market remained stable.

But even as fruit growing was becoming more productive, grape growing and wine production was beginning to take hold as well. The first grapes in the Okanagan were planted by Father Charles Pandosy at the Oblate Mission near present-day Kelowna in 1859, and were used for sacramental purposes. After this time, several small vineyards began to take shape, but they were quashed by Prohibition in 1917, which forced early farmers to remove their vines.

After the end of the Prohibition in 1921, the wine industry gradually picked up speed in the Okanagan, but it was not until the premiership of W.A.C Bennett in 1952 that wine production got the boost it had been waiting for. Bennett was very interested (and personally invested) in the wine industry. He was, after all, one of the original partners of the Calona Vineyards near Kelowna. Calona, founded in 1932, is today the longest continually operating vineyard in the province.

In 1962, Bennett's government mandated that wines could not be labelled as BC wines unless they contained at least 50% BC grape juice. This number only increased as the decade continued, encouraging BC wineries to support the local vineyards of the Okanagan. By the end of the 1960s, BC wines had to include at least 80% BC grape juice to claim to be local wines. As a result, the province's grape harvest grew by leaps and bounds: in 1961, just 1,600 tonnes of BC grapes were harvested; by 1970, this number had reached 9,038 tonnes.5

The final event which brought vineyards to the forefront of the Okanagan's agriculture took place in the late 1980s: the rise of the European vinifera varieties of grapes. In 1989, the BC government sponsored local vineyards to pull out their native grape varieties and replace them with these vinifera varieties, which produced wines of a higher quality. This switch, along with the Canada-US Free Trade Agreement, which came into effect that same year, led to the rapid increase in the success and productivity of the Okanagan wine industry.

Today, the economy of the South Okanagan still centers around agriculture, although tourism is a big part of the story now too. Many of the region's old orchards have been replaced by sprawling vineyards and wineries, but the fruit industry remains a key part of the regional economy as well. And the occasional cattle ranch still nestles in the hills, a reminder of the early days of white settlement in the South Okanagan.

2. "It's Hard to Be Chinese in Penticton." Journal of the Okanagan Archive Trust Society, Vol 3 No.7, Winter 2019/2020, pp. 20-21.

3. Webber, Jean. 169.

4. 3. Webber, Jean. 180.

5. "History of Wine Making in the Okanagan." Treehouse Wine Tours. URL: https://teehousewinetours.com/history-of-wine-making-in-the-okanagan/

Penticton's Event Culture

Story Location

Ever since Penticton's early days, local events and celebrations have been a big part of the community. Events tied to agriculture and the outdoor landscape have taken place since the early twentieth century in Penticton, which is perhaps not surprising given the region's unique ecosystems and an economy which has always been based around agriculture.

* * *

In the 1900s, rodeos and horse races were popular across the South Okanagan, and Penticton had a race track, complete with a grandstand. The King's Park Rodeo Grounds, located where the Convention Centre is today, were a popular spot after their completion in 1910. The Penticton Turf Club, founded around the same time, organized rodeos and horse racing events that drew huge crowds of over 2,000. Hans Richter, a local champion rider from nearby Keremeos, also hosted travelling rodeos in Penticton, bringing with him his collection of about 40 bucking horses.1

As the town of Penticton grew and flourished with the coming of the Kettle Valley Railway, which was completed in 1916, the want for an annual summer event in the town increased. Dominion Day, now known as Canada Day, provided a chance to celebrate, and a "Sports Day" was held on July 1st for a number of years. The event gradually grew larger, and in 1935 one of the biggest parades to be held in Penticton took place.

Yet the festival was not to last. Efforts to create a traditional summer celebration in Penticton fell to the wayside during World War II, as the community turned their attention to the war effort. It was not until 1947 that Penticton first organized what was to become the city's biggest, most popular summer celebration: the Peach Festival.

Held in mid-August to celebrate the ripening of Penticton's peaches, the festival was created to encourage tourism to Penticton and to promote the city's agricultural richness. The first festival, held in August of 1948, honoured Penticton's past with a rodeo, along with a parade and the crowning of a Penticton Queen (to be named Queen Val Vedette, after three varieties of peaches: the valiant, the veteran and the vedette). The celebration also included dancing, bands, and a midway with nine rides.

The Peach Festival was a definite success. By the next year, it was estimated that as many as 30,000 attended. New events were added in the coming years: wrestling and boxing in 1950 and square dancing in 1954. In 1971, a team of three jets put on a breathtaking acrobatic display during the festival—a team that would later become known as the Snowbirds.

But the festival did not always go smoothly. In 1991, a riot took place during Peach Fest, after a show by American rapper MC Hammer. Rioters smashed windows, looted businesses and, most dramatically of all, rolled the famous Peach concession stand into the Okanagan Lake. The Riot Act was read by Jake Kimberley, mayor of Penticton at the time, and the outnumbered Penticton RCMP struggled to subdue the crowds.2

Today, memories of the riot are still vivid. There is humour in the recollections too: in 2018, the new owner of the Peach concession stand, Diana Sterling, posted on Facebook in a pun-filled plea, asking for the rioters to come forward to talk about the night "over some ice cream."

"It's time," the post read. "I need closure. I need to find the peach rollers."3

Despite the riot, the Peach Festival remains today a beloved part of Penticton culture, and it is still going strong, despite having to cancel in 2020 and 2021 due to Covid-19. Numbers have continued to increase, with 80,000 event visits recorded during the 2016 festivities. In 2018, the festival had an economic impact of $3.6 million locally, according to a study by the City of Penticton.4

Penticton has also hosted a number of sporting events, one of which is the famous Ironman triathlon. The first Ironman event outside of Kona, Hawaii, took place in Penticton in 1983, with a total of 25 participants—24 men and one woman. The event included a 3.8-kilometre swim in the Okanagan Lake, a 180-kilometre long-distance single-loop bike course (one of the few single-loop long-distance bike courses in the world), and a 42-kilometre run through Okanagan scenery.5 Registration numbers reached 3,000 in some years, before being capped at 2,500.

In 2012, the City of Penticton and Ironman did not renew their contract, and the event moved instead to Whistler for seven years. Happily, the City announced in 2019 that Ironman Canada would be returning to its hometown of Penticton, with a new five-year contract having been signed. The triathlon will once again become a staple in the event calendar of the city.

2. Patton, Kristi. "Decades Don't Diminish Memories of Riot." Penticton Western News, July 2011. URL: https://www.pentictonwesternnews.com/news/decades-dont-diminish-memories-of-riot/

3. The Peach. Facebook, July, 2018. URL: https://www.facebook.com/thepeachinpenticton/photos/a.886093528167624/1578883625555274

4. "History." Penticton Peach Fest. Accessed on May 21, 2021. URL: https://peachfest.com/history/

5. "Subaru Ironman: Penticton Canada." Ironman. URL: https://www.ironman.com/im-canada

6. Wassner Flynn, Sarah. "Ironman Canada to Return to Penticton After 8 Years Away." Triathlete, 2019. URL: https://www.triathlete.com/culture/news/ironman-canada-to-return-to-penticton-after-8-years-away/

Then and Now Photos

View from Vancouver Hill

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 185

1907

This view of Penticton was taken in 1907 from Vancouver Hill, looking northwest towards the Okanagan Lake. The Penticton hotel is on the far right on the photo, with the Welby Barn to the left of it, and the town laid out beyond.

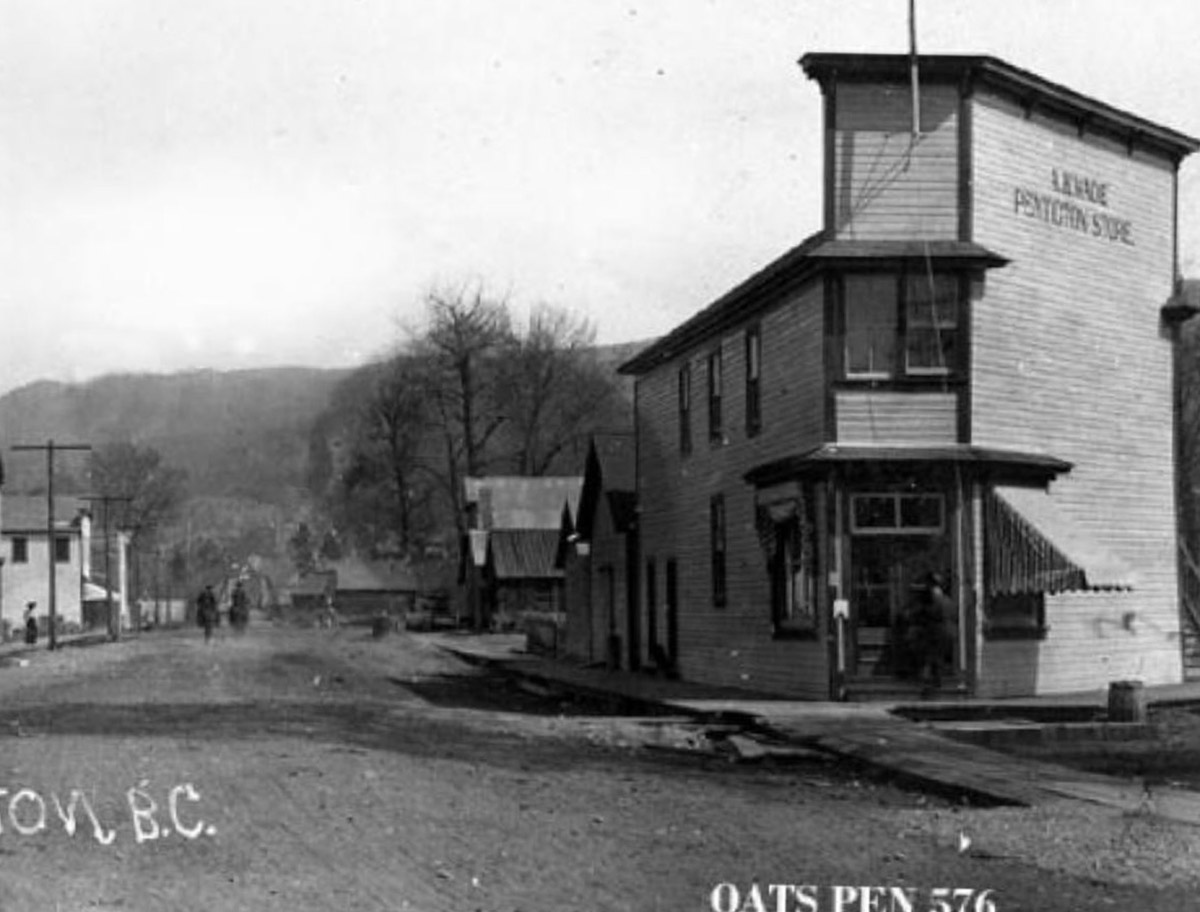

A General Store

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 576

1906

The building in this photograph was a general store belonging to Alfred Wade, who was Penticton's first reeve. Note the wood plank sidewalks and the two men on horses farther down the street.

Main Street Looking North

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 189

1911

This photograph from 1911 looks north down Main Street towards Okanagan Lake. An early car and a wagon travel down the road, and the Bank of Montreal is to the left of the street, with the Bank of Commerce on the right.

Steamships on Okanagan Lake

1914

This photo shows the steamships the SS Sicamous and the SS Okanagan in Okanagan Lake, with the Sicamous at the CPR wharf and the Okanagan astern. The SS Okanagan was constructed in 1907, while the SS Sicamous joined the CPR fleet in 1914. The vessels were an important part of Okanagan life, providing reliable, luxurious travel between otherwise isolated communities.

Sailboats on the Okanagan Lake

1915

This photograph from 1915 shows seven sailboats on the Okanagan Lake near Penticton.

Okanagan River Bridge

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 203

1925

This photograph from 1925 shows the old lift span bridge which used to cross over the Okanagan River off of Lakeshore Drive.

The Incola Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 020

1928

This photograph shows the Canadian Pacific Railway hotel, the Incola, which was situated near both the wharves and the railway station, making it an ideal spot for travellers to spend the night. At the end of Martin Street, you can see both the SS Sicamous and the Tug Naramata at the dock. Travellers bound farther north up the Okanagan Lake would often stay overnight at the Incola before boarding the SS Sicamous in the morning.

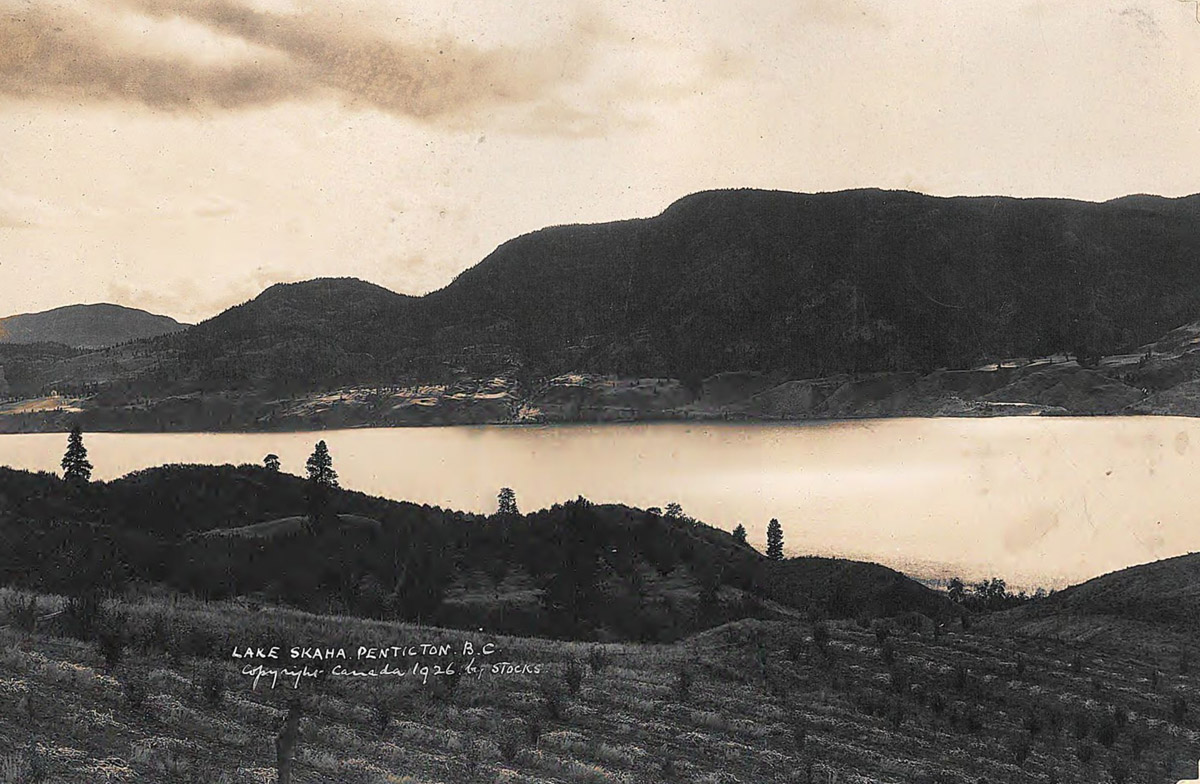

A View Over Lake Skaha

1926

This view over Skaha Lake shows young orchards growing in the foreground. Today, most of these hills are covered instead with the grapevines of vineyards and wineries.

The First Airmail

Okanagan Archive Trust Society AIR 112

1935

This photograph shows the first flight from Penticton which left for the purpose of delivering mail. The postmaster stands beside the plane, ready to hand his parcels to the pilot. The Air Mail Service division of Canada's postal service officially opened in 1929. Air mail cost five cents an ounce.

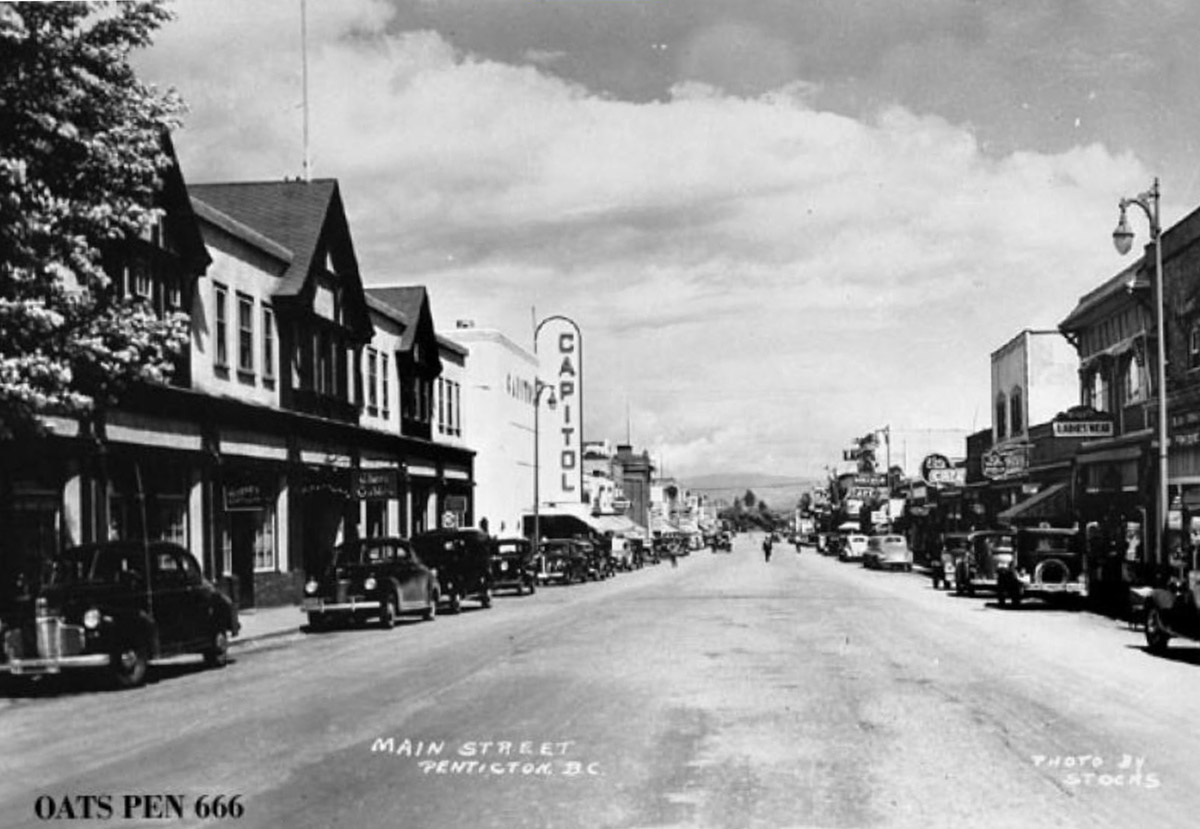

Main and the Three Gables Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 666

1938

This photograph shows the 300 block of Main Street, looking north towards the lake. The Three Gables Hotel, on the left of the street, opened in 1933 and was in operation until it was destroyed by fire in 2000. Farther down the street is the Capitol Theatre, which was opened in 1937, just a year before this photo was taken.

Skaha Beach

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 249

1940

This photo shows swimmers at Skaha Beach in 1940 enjoying the waters and sands of the lake shore.

Peach Festival Dancing

Penticton Museum Archives 2364

1948

This photograph shows a busy Main Street during Penticton's annual Peach Festival, as festival-goers dance in the street. The festival has been an annual event ever since 1948, taking place in August each summer.

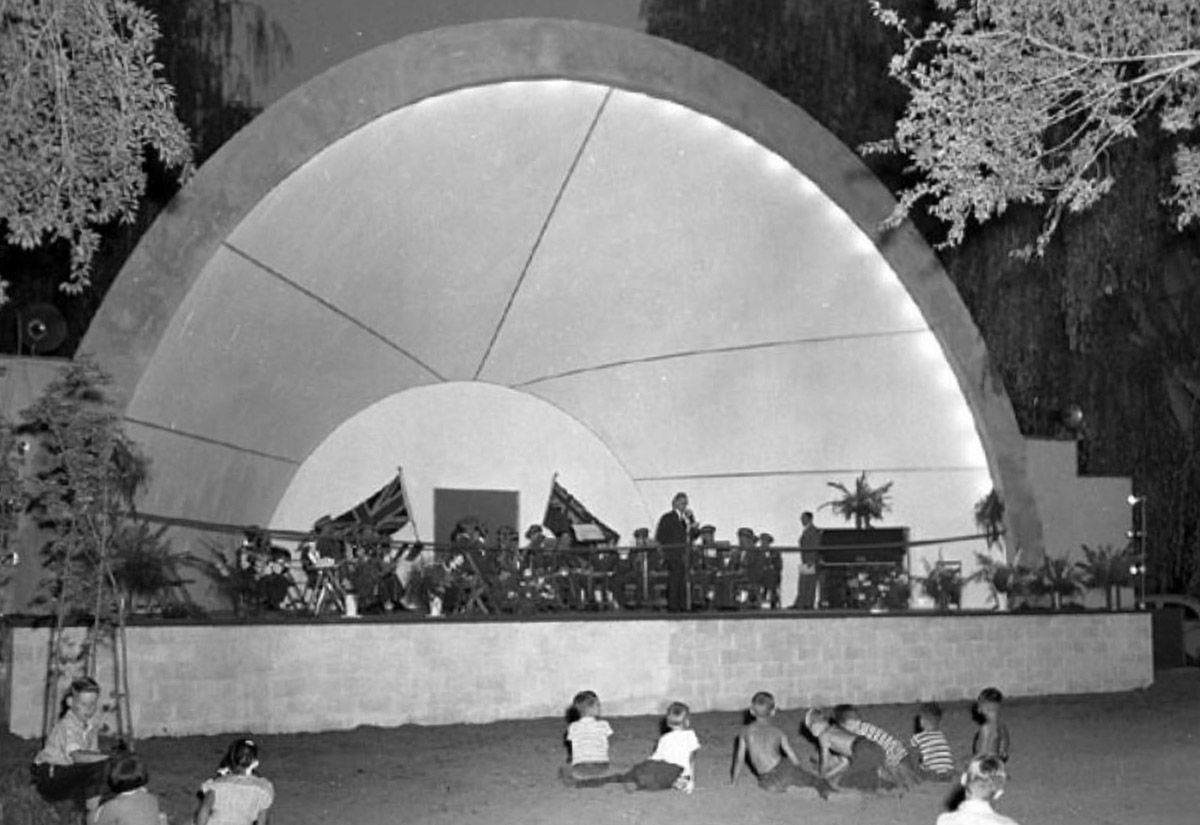

Gyro Bandshell

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 564a

1951

This bandshell was constructed in 1951 to replace earlier bandshells which stood in this place. The photo shows a concert taking place in the bandshell at night—an occurrence which is still common in the park today.

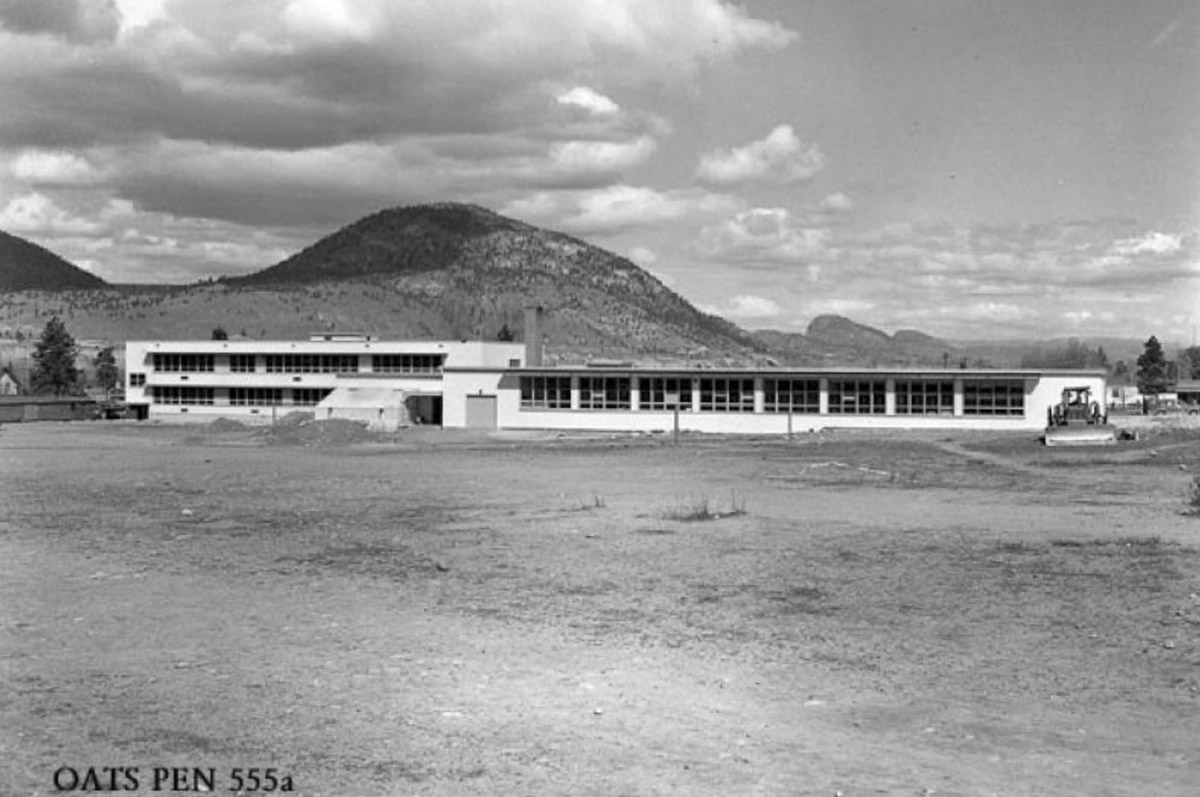

Construction of High School

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 555a

1952

This high school building was under construction from 1949 to 1953, when it was completed. It was built to replace the first Eckhardt Avenue senior school, which had been built in 1935 and burned down in January of 1949 in a spectacular fire. The school in this photograph was demolish in 2008 and is now the location of a very large parking lot.

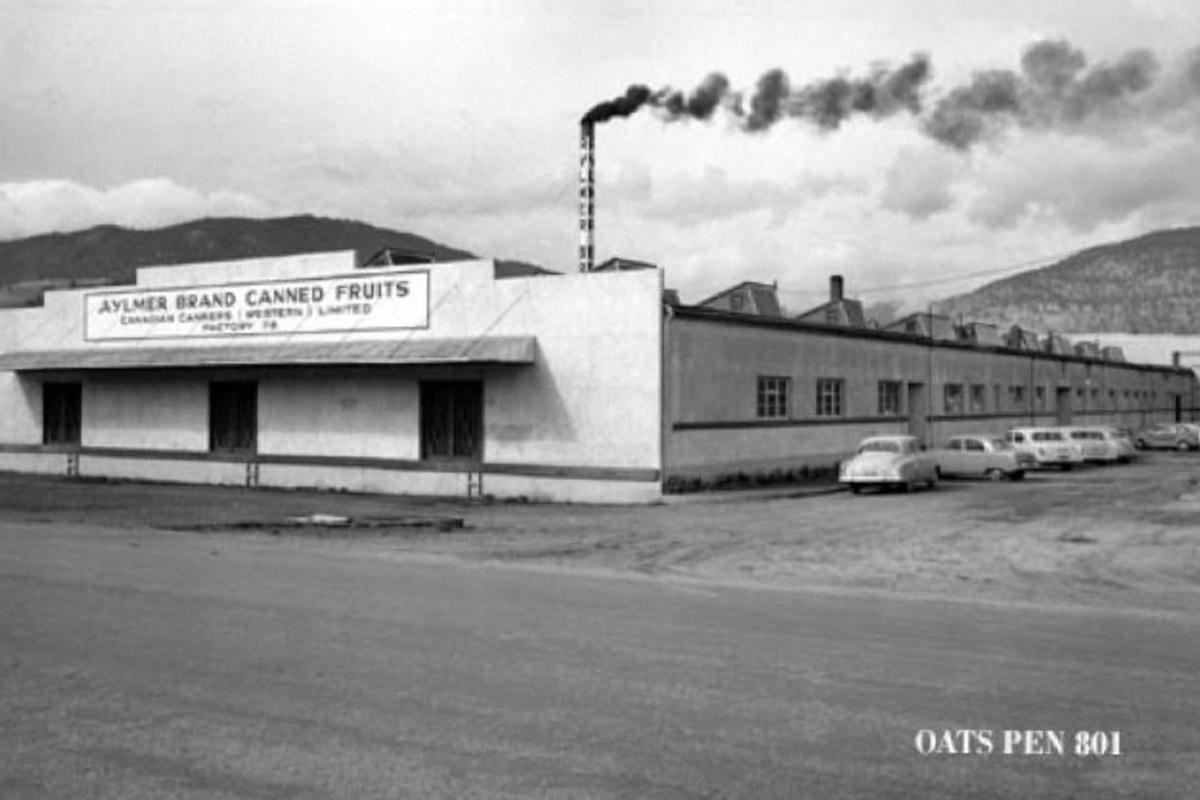

Aylmer Fruits Cannery

Okanagan Archive Trust Society PEN 801

1954

This photograph shows the Aylmer Fruits Canning Factory, which operated from the 1930s until the 1980s and was Penticton's main canning factory. The factory canned both fruits and vegetables and provided employment for many locals, but was eventually shut in the 1980s.