For millennia, this land has been the traditional territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation, who lived sustainably off the land, fishing, hunting, foraging, and developing complex trading networks across the region and beyond. Europeans first came to the area in 1811 as part of the fur trade, and settlement by white farmers began soon after. In its early days, Naramata had many names: Nine Mile Point, East Summerland, and Brighton Beach. The town was founded in 1907 by real estate developer John Moore Robinson, who had previously laid out the towns of Summerland, directly across the water, and Peachland. Robinson clearly fell in love with Naramata, as he chose it as his permanent home, but it took him a while to settle on a name for the community. In the end, "Naramata" was chosen, though there are many different stories as to why, one of which claims that the name came to Robinson during a séance. Once established, the town grew into a small, thriving farming community. The school was opened in 1907, and the historic Naramata Hotel, owned by Robinson, in 1908. Today, the Naramata Bench is covered in lush vineyards, and fruit trees still grow in Naramata's plentiful orchards. The Kettle Valley Railway hiking and biking trail brings visitors to the community all summer long.

This project was made possible through a partnership with Visit South Okanagan, with support from Discover Naramata.

We respectfully acknowledge that Naramata is within the ancestral, traditional, and unceded territory of the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation.

Explore

Naramata

Stories

The Kettle Valley Railway and Naramata

Story Location

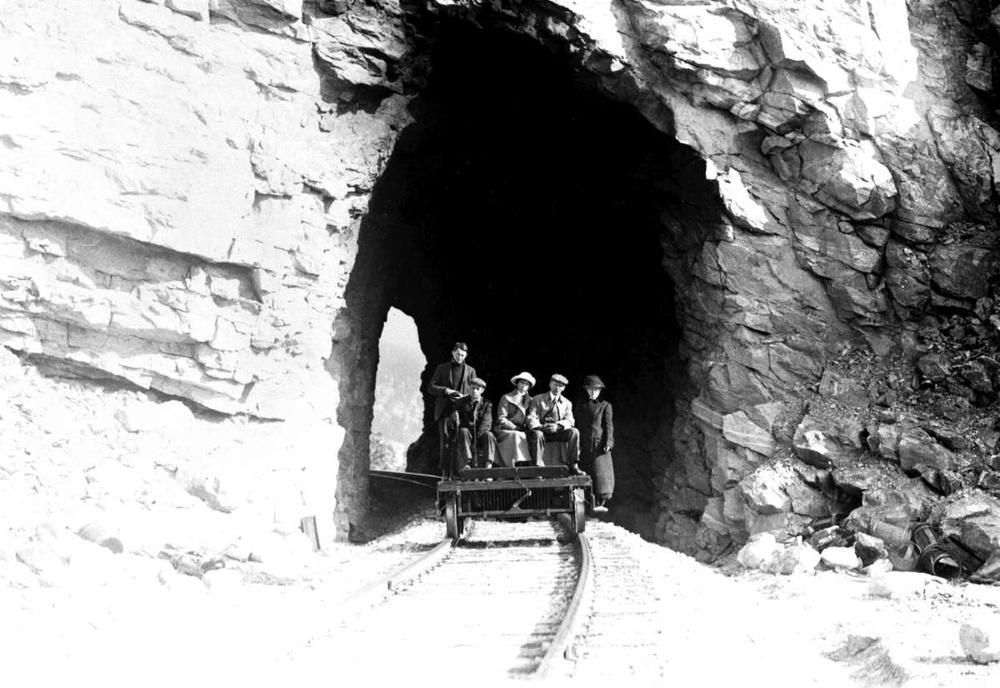

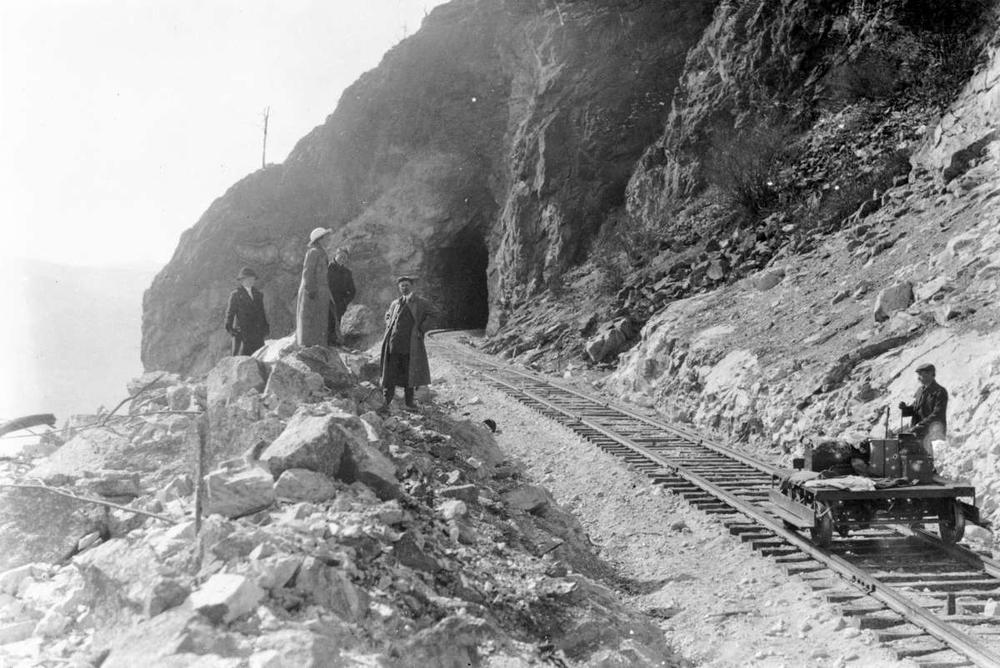

The "Little Tunnel" outside Naramata is one of the highlights of the famous Kettle Valley Rail (KVR) Trail. When the trail was still a railway, it ran north towards Naramata from Penticton and passed Naramata a little above the community. While the railway is long gone, evidence of its construction still remains.

* * *

When the KVR was built, it brought a flood of railway workers into the area. The 96 kilometer section of railway running from Penticton to Hydraulic Summit was one of the most challenging portions of the railway to construct, and almost 1000-1500 workers toiled on this section alone. In a 1970 article in the Vancouver Province, contractor John Rounds remembers the difficulty of the construction, “They tried 60 per cent dynamite, but it wouldn’t work on the granite. Then they tried 75 per cent and it wasn’t much better. In the end they used 90 per cent gelignite, which is almost straight nitro.”1

The construction of the "Little Tunnel" took about a month, and railway workers camped nearby on the KVR right of way. The workers were camped here long enough to build some infrastructure, which still exists today. Near the tunnel one can find rock ovens, which were built by railway workers to bake their bread. While the men on the railway likely enjoyed fresh bread daily, the ovens may have served another purpose.

In cold winters, it was necessary to thaw frozen dynamite so that it could be used. However, the method most often used by the workers wasn't as effective as they would have liked. To thaw the dynamite, workers used a metal drum surrounded by metal pipes, the drum was then filled with warm water and dynamite was pushed inside the pipes so it could thaw slowly. However, this method was sometimes disregarded in favour of quicker methods. According to rounds, “This didn’t work too well and I have always thought that the ovens were built to thaw out the dynamite. They could build a fire in them, until the rocks were hot, remove the coals and then stick in the dynamite. Perhaps they used them for both bread and dynamite.”2

Unsurprisingly, heating dynamite in an oven was highly dangerous and there are several historical accounts of people who were killed when a quickly heated stick of dynamite suddenly exploded. Some men also wore dynamite against their skin to keep it from freezing in low temperatures, an action that could also trigger an unexpected explosion.3

Injuries and deaths resulting from mishandling of dynamite and other explosives were not unheard of during British Columbian railway construction. Thankfully, there are no records of rock oven related dynamic explosions during the KVR construction.

The KVR brought change to Naramata. Previously, the easiest access had been by steamboat. Mail and other deliveries to Naramata often went by rail to Okanagan Falls, where they were picked up and transported by wagon the rest of the way. The stop for Naramata was at Arawana Siding, near where Arawana Forest Service Road and the KVR intersect today. The train would only stop there when the section man, who lived in a house by the tracks, flagged it down. Passenger service for the KVR ended in 1964 and the buildings at Arawana Siding were torn down in the 1970s. Finally, in 1989, the KVR's last freight train steamed down the tracks and the railway was put out of service.

2. Ibid.

3. Jeremy Agnew, Medicine in the Old West 1950-1900 (Jefferson, NC: Mcfarlane & Company Inc., Publishers, 2010), 164. E-Book.

The Story of J.M. Robinson

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 030H

Story Location

No figure looms larger in the history of the central Okanagan than eccentric entrepreneur John Moore Robinson. This man founded not only Naramata, but Peachland and Summerland as well. Naramata was the last community established by Robinson, and where he ultimately chose to settle down.

The name Naramata was the last in a long line of names applied to this site on the eastern side of Okanagan Lake. Settlers first deemed it the unimaginative moniker "Nine Mile Point" for its location nine miles north of Penticton. Robinson then named the area East Summerland as it was across the lake from Summerland. Then, he changed his mind and renamed it "Brighton Beach" after a beach in New York City where he had received his education. This name must’ve not been original enough for him, because the name was then changed one final time. There are several legends around the origin of the name. Allegedly, Robinson himself told people that he had come to the name during a seance where the town's medium, Mrs. Gillespie, channelled an unnamed "Indian Chief" who spoke of his wife Narramattah. Regardless of whether this story is true, the name finally stuck and Brighton Beach would forever be known as Naramata.1

* * *

Robinson started Naramata from 3500 acres of land that he had purchased from the South Okanagan Land Company. Once the community was established, Robinson was tied to practically every business that appeared: the bank, post office, the Naramata Supply Company, the Naramata Hotel, and a bottling plant for seltzer water, to name only a few.

In the early days, transport to Naramata was tricky, and Robinson offered his personal steam yacht, the Rattlesnake, as a ferry service between Naramata and Summerland. By 1907, Naramata had a rough wagon road connecting it to Penticton, and a single-room schoolhouse. The community grew and Robinson began to develop more leisurely facilities. The first of these was the beautiful Naramata Hotel, which he chose to live in after it was built. This hotel was built with 17 rooms and featured cottages for rest cures, a bowling green, tennis courts, croquet grounds, a lacrosse field and a baseball diamond.

He didn't stop with the hotel, as after it was completed in 1908, he went on to build a so-called "opera house" on the top floor of the Naramata Supply Company Building. The room was actually a large meeting room, which hosted meetings, church services, concerts and plays. The Penticton Press reported on the opening, “The opera house is a handsome structure, the auditorium of which is capable of seating between 200 and 250 spectators. The stage is one of the most attractive features of the building. It is beautifully decorated with scenery and the drop curtains are certainly up to date in the mechanism of their operation. Naramata is the second youngest town in the Okanagan and the population is not large, but the fact that an opera house was deemed one of the first requirements of the new settlement goes to show that the people who intend on making their homes there purpose getting the most out of life."2

In 1908, Naramata held the first of what would become their famous Regattas. A regatta is a sporting event consisting of boat or yacht races. In Naramata, the most popular of these races were the "war canoe" races, where the winner would receive the Robinson Cup. These regattas were more than just the races however and also featured baseball games, refreshments, and performances at the Naramata Grandstand. This grandstand was built just to the south of the hotel and could seat 800 people. Sadly it burned down only a few years after it was completed.

Another early feature of Naramata was the beautiful Manitou Park. It was opened in 1935 and has been the heart of Naramata's recreation ever since.

https://discovernaramata.com/local-history

2. Craig Henderson, "A handsome structure opens in Naramata" My Naramata, April 2018. Website. https://www.mynaramata.com/show2893a24s0x80y1z/Handsome_Structure_Opens_in_Naramata

Naramata Agriculture

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 079

Story Location

Like much of the Okanagan, before Robinson’s dream of blooming orchards could be achieved, the land had to have irrigation systems set up. J. M Robinson, Naramata founder and ambitious entrepreneur created the Naramata Irrigation Company to build the water delivery system. The company earned back its investment through charging the orchards for the water.

* * *

When the system was built much of it was constructed from wood, as it was cheaper than pipe. The water was funnelled from the hills above Naramata and even as far away as a lake east of Penticton. The water travelled downhill through a system of gullies and wooden flumes until it eventually reached the thirsty orchards.

In 1913, the Naramata Irrigation Company was granted a license by the provincial government for better irrigation infrastructure and they built a dam at a landlocked lake that flooded with snow melt every spring. This dam, and the others that followed, helped immensely to irrigate the Naramata Bench.

For a couple decades, orchards thrived in Naramata. Orchardists grew apples, pears, peaches, plums, apricots and cherries, many of which are still grown in Naramata today. In the 1930s, two events transpired that dealt severe blows to Naramata's fruit industry.

First was the Great Depression, when markets for Okanagan fruit evaporated practically overnight. The orchards became unprofitable, and development in Naramata slowed. During this time, one could purchase a waterfront lot in Naramata for only $10, which amounts to just a little under $200 today. Can you imagine buying waterfront property in the Okanagan for less than the cost of a new laptop? Despite the price, there were few buyers.

In addition to the financial burden of the Great Depression, orchardists were also fighting a direct assault on their fruit trees. In 1928, the provincial government decided to introduce elk in the Kettle Valley. Unfortunately, the elk escaped the control of the government when they were unloaded from the train into an enclosure so they could graze and fled into the hills near Naramata.

No one realized the impact the escaped elk would have until the following spring, when they began happily grazing on the local orchards. Desperate, the community organized an elk hunt to try and control the numbers. Unfortunately, the hunt failed to sufficiently control the population. In the following years, one very cold winter allowed the elk to walk across the lake, and they began causing issues in Summerland as well.

While there are still many orchards in Naramata today, vineyards have filled many of the former orchard lots and many award-winning wines are born on the Naramata bench.

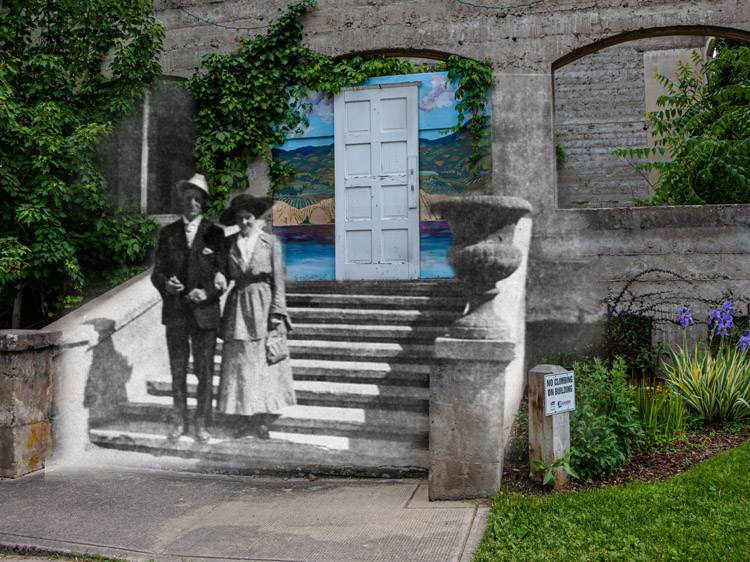

Then and Now Photos

The Maude Moore at Dock

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 108

1906

Originally built by W.J. Snodgrass of Okanagan Falls to run on Skaha Lake, the ship the Maude Moore, seen here at the government dock in Naramata, was purchased by Naramata founder J.M. Robinson in 1905. She served as a ferry between Naramata and Summerland until 1911.

Naramata Supply Company

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 043

1907

The wooden building to the right of this photograph is the Naramata Supply Company, owned by J.M. Robinson, who founded the town of Naramata. The empty area in the background of the photo is now the site of the historic Naramata Inn, which was also built by Robinson.

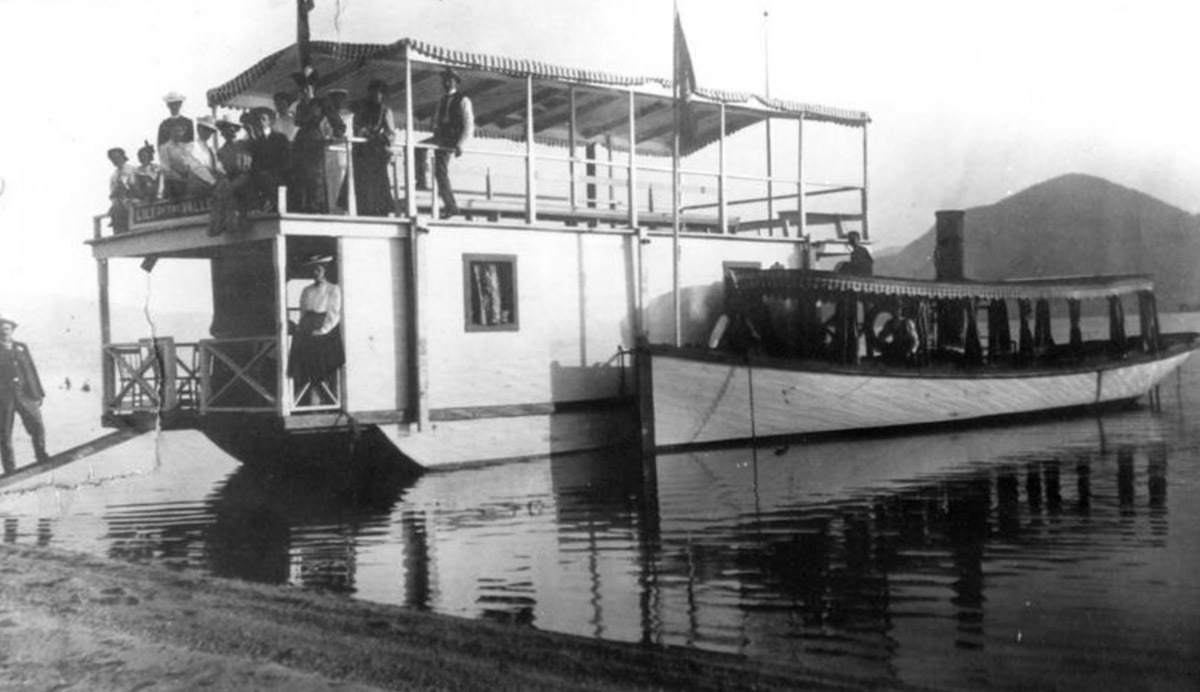

Boats at Dock

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 107

1907

In this photograph, two of J.M. Robinson's boats are docked at the wharf in Naramata. The Lily of the Valley is to the left, with a crowd of people aboard, while the Maud Moore is to the right.

A Canoe Team

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 084B

1910

This photograph shows a group of Naramata citizens in a canoe near the lake shore. The canoe team is mixed gender, with four women and three men.

The Grand Stand and Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 028

1912

On the left of this photograph of First Street in Naramata is the grand stand, used to watch the community's popular regattas. The Naramata Hotel is beside the stands. Naramata held its first regatta in 1908, and the sporting event became so popular that the 800-person grand stand was built soon after, though it burned down just a few years after completion.

A Cricket Team

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 077C

1950

This cricket team, posing for a team photo in 1950, was playing in the Cricket Champions in Manitou Park. They clearly did well, as is evidenced by the large trophy displayed in front of them.

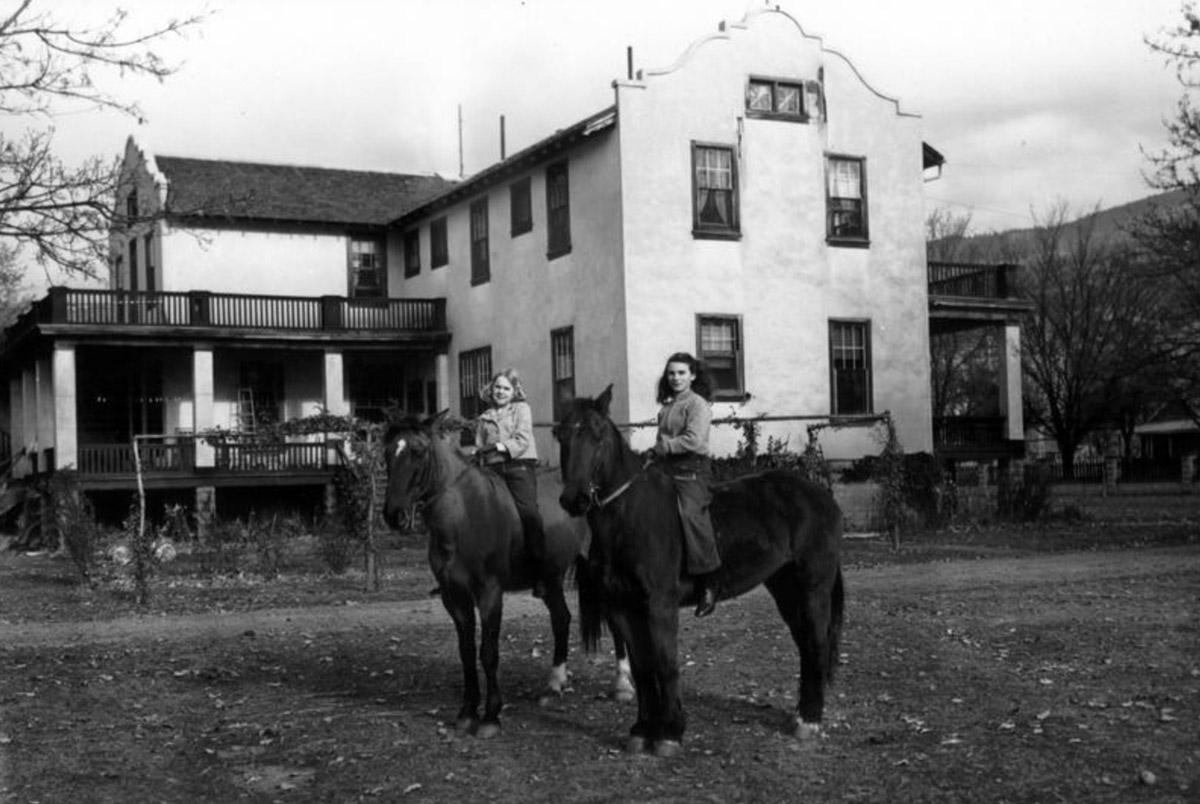

Riders at the Naramata Hotel

Okanagan Archive Trust Society JMR 033A

1941

Two young girls ride in front of the Naramata Hotel in this photograph from 1941. The hotel was the first building in the town to have running water and electricity for its lights. It even had a basic telephone connection to the Naramata Supply Company building.