Walking Tour

Quarry Park

Exploring Stonewall's Industrial Past

Andrew Farris, Elyse Abma-Bouma

From the 1880s to the 1960s the limestone quarries were the economic lifeblood of this community. Today, the quarries are silent, but their legacy remains in the kilns that tower over this park, and the town itself.

In this tour we will learn the story of these quarries, beginning with the formation of the limestone beneath your feet some 450 million years ago, and moving on to tell the stories of the people who worked here, the techniques and technologies they used, and the economic forces they contended with.

This tour takes a circuit around Stonewall Quarry Park, beginning at the Stonewall Quarry Park Heritage Arts Centre and concluding at nearby Kinsmen Lake, which was once a part of these quarries.

NOTE: Some of the photos recreated for this tour are rough approximations of the location of the original photo and not the exact right spot.

This project is a partnership with the Town of Stonewall.

1. 450 Million Years in the Making

Stonewall: Turning a Century, Plate 42

ca. 1930s

This photo shows three limestone kilns towering over the quarry. Today, these structures and the deformed landscape provide a hint as to what the land was used for over a century ago, when it was a hub of activity - sounds ranging from the scraping of shovels to the whirring of industrial equipment were commonplace.

This park helps to tell a story that should be known to all who visit Stonewall and especially the generations of people who call it home: these quarries, for generations, were the economic lifeblood of the community and are the primary reason the town was founded.

Our story begins with the earth itself, and the rich deposits of red limestone that lie beneath your feet. Those rocks have their own fascinating tale stretching back some 450 million years.

* * *

In the earth's past, ecosystems have persevered for tens of millions of years, a span of time so long it is difficult for the human mind to grasp. Over that whole time, millions of generations of life lived and died and carpeted the floor with their organic remains. Over time they combined with silicates and were compacted under the weight of later generations of life. Eventually they were pressed deep into the earth where they were heated up and broken down into fine grains. Eventually those grains solidified into limestone.3

Variations of this process are how many sedimentary rocks and minerals are formed. Looking at geology today can tell us much about the ecosystems that existed on that spot eons ago. Coal is formed from the compressed remains of forests. Oil comes from the bacteria-sized plants and animals--algae and zooplankton--that lived in oceans.

However, the formation of limestone is a little bit different: it is primarily made from calcium carbonate; the material that oysters, clams, mussels, and corals use to make their shells, as well as the bones of sea creatures.

The shellfish-beds at the edge of the ocean 450 million years ago, combined with clay, created all the red limestone you see around you today. The limestone around Stonewall still contains the fossilized skeletons of some of these creatures. These were considered noteworthy enough to merit a site visit by the International Congress of Geologists in 1913, who travelled from a conference in Toronto to view them and were reportedly very impressed.4

The first Indigenous people probably came to this place around 14,000 years ago, a much, much smaller span of time that is still so far in the past that it is difficult for the human mind to grasp. They found a ridge of limestone that rose above the surrounding countryside. Numerous trails on and around the ridge show how frequently Indigenous peoples passed through this area. When Europeans came to this place some 150 years ago, the Indigenous told them they called the ridge "Thunder Hill."5

2. Why Limestone?

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

1920

A photo taken mid-way through the quarry's working life, showing both old (horse and buggy) and new (car and tractor).

What is it about limestone that makes quarrying it worthwhile? Limestone is, after all, a fairly common rock, accounting for about 10% of all the world's sedimentary rocks.1 It being common shouldn’t be a negative - it is an exceptionally useful rock. Blocks of it can be used for construction; it can be crushed and used in everything from roads to toothpaste; or it can be burned so that only lime is left over, which is a disinfectant and key ingredient in cement and dozens of other products.

* * *

When crushed, pieces of all sizes have their uses. Large chunks are durable enough to be used as bedding for roads, railway tracks, and drainage pipes. Smaller pieces can be used as aggregate in roofing materials, or in soil fertilizer as a neutralizer. Even smaller granular pieces are key components of cement, concrete, and mortar, used in metal smelting, and can be added to toothpaste to make it white.

If limestone is exposed to prolonged heat, it breaks down into lime, a highly corrosive substance that has all sorts of uses. It's a powerful disinfectant, and sometimes used in burials during epidemics to halt the spread of infection. It's an important ingredient in plaster and used in many industrial processes, like refining sugar, bleaching paper, and manufacturing glass, shingles, or detergents.2

Making lime means exposing limestone to flames in kilns, and this requires an enormous amount of fuel, usually wood or coal. Procuring fuel for lime production can itself have far reaching effects. The Mayans in Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula were especially fond of coating all their temples with a lime-based plaster. One popular explanation for their civilization's mysterious collapse in the 9th Century CE is that by cutting down trees to fuel the kilns, they deforested the surrounding lowlands. The deforestation spurred local climate change, causing prolonged drought, widespread famine, and, ultimately, endemic warfare. Within a few decades, the Mayan population collapsed and their great cities were reclaimed by the jungle.3

3. Bridging Supply and Demand

Stonewall: Turning a Century, Plate 41

1930s

This photo shows a series of rail spurs leading up to rock faces in the bottom of a limestone quarry. These were narrow-gauge railways that allowed horses to easily haul wagons right up to the rock face and load limestone blocks back to the central collection point.

The railway was a pivotal technology in allowing the rise of Stonewall in the first place. In the 1880s the limestone here was identified as some of the best in the region, and was matched by a significant demand for limestone to build the young metropolis of Winnipeg, which is only around 30 kilometres away . The big question was “How can we get the limestone from Stonewall to Winnipeg?” and the answer? The railway!

* * *

As people and capital surged into Winnipeg the city boomed. The population grew from a few thousand in 1880 to over 150,000 by 1913, making it the third largest city in Canada.1 In the process, Winnipeg became the factory of Western Canada: Even as cities like Calgary, Edmonton, and Saskatoon popped into existence, Winnipeg still boasted 50% of all the manufacturing on the prairies in 1910.2

Winnipeg's rough-hewn wooden buildings of the 1870s were rapidly replaced by grand, modern stone buildings, many made of limestone--and those factories also had an insatiable thirst for lime. Where to get it from?

On August 19, 1881, the Manitoba Free Press ran a front page feature excitedly recounting a survey trip to Stonewall by Joseph-Pierre-Michel Lecourt, Manitoba's most prominent architect. He was looking for stone suitable to build the Lt. Governor's residence and the province's Legislative Building (the previous one, not the current one). He was impressed and reportedly "pronounced the stone from Stonewall to be unequalled in Manitoba, and accepted it for the buildings named above."3 Such a prestigious endorsement could not help but be noticed by every other architect in Manitoba.

But how could the limestone and lime get to Winnipeg?

In the late 1880s there were no highways or long-haul freight trucks--there were barely any paved roads in Canada at the time. If limestone was to be moved by road, it would have to go by horse-cart along muddy, rutted tracks, which was highly impractical. Canals and rivers were crucial for moving heavy goods in other parts of Canada during this period, but Stonewall was not near any navigable rivers.

Fortunately, Samuel Jackson's arrival in Stonewall around 1880 coincided with the arrival in Manitoba of the CPR. The tracks reached Winnipeg in 1881, a mere 30 kilometres from Stonewall. Even though only a few homesteaders lived around Stonewall at the time, the Manitoba government saw the value of the limestone and wasted no time building their own branch line to Stonewall that very same year.

By the end of 1881, Stonewall had a secure supply of a valuable resource, a market for it, and a way to get it there. All the pieces were now in place for Stonewall to take off.

4. The Quarriers

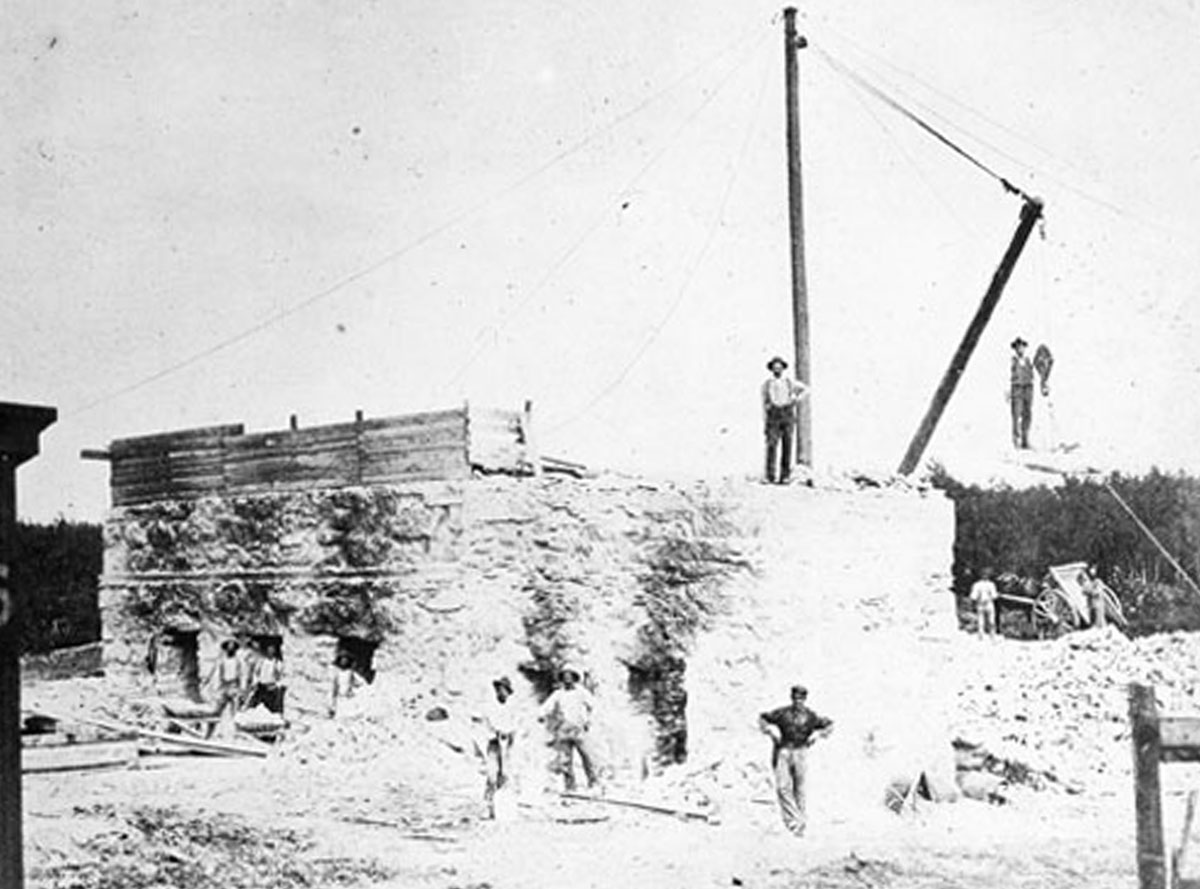

Stonewall: Turning a Century, Plate 21

ca. 1890s

A group of workers take a break from work to pose for a photo. Notice the total absence of hardhats, gloves, goggles, or any of the safety equipment we associate with industrial sites today. Work in the quarries was not for the faint of heart.

Samuel Jackson's first quarry at the southeast corner of Stonewall was just the first of many. After the arrival of the railway in 1881 a number of enterprising men flocked to Stonewall to establish their own small enterprises. Within a few years the quarries formed a near continuous arc skirting the town, from its southeast corner, north along the east side of Provincial Road 236, and then west across Quarry Park where you are standing.

These quarries needed workers, and they also needed places to live. As more workers and their families were drawn to Stonewall, it did not take long for a thriving little town to grow up in the area bounded by quarries on the north and east sides, and the railway on the south and west.

* * *

This meant it was cheap for someone to start up their own quarry, allowing a variety of small quarries to thrive in these early decades. It also meant these small operations needed a relatively large number of workers. In 1884 Major Bowles' little operation employed on its own 36 stonecutters and 25 quarrymen.1 In 1904 there were five quarries in operation, and one of them employed over 150 people.2

The entrepreneurs who established the quarries and ultimately rose to prominence in Stonewall fit a profile: male, Anglo-Saxon, and from middle-class--or perhaps lower-middle-class--backgrounds. The similarity of their profiles was awkward in contrast to the ideas firing the imaginations of the millions who settled in Canada’s West - that with enough grit and gumption - and a dash of luck - anyone could make it; their place in life before arriving here didn’t matter.

Success in this meritocracy was certainly possible if you fit the above profile, but it was very difficult if you did not. Women, First Nations, and people that didn't originate from the British Isles were much less likely to realize the rags-to-riches dream in 19th Century Canada. It would be some decades before this began to change.

Most of the workers in Stonewall fit a fairly similar profile to their bosses. In 1911, 80% of Stonewall's population were from the British Isles, the only other significant group being 11% from Southeastern Europe.3

The census numbers also don't account for the large number of seasonal workers who didn't set down roots in Stonewall. Demand for limestone see-sawed back and forth over the years, determining the number of jobs available. When times were good young men in Winnipeg looking for work would flock to Stonewall. When business slowed down they would be laid off and return to the metropolis to start a new job search.

5. The Art of Quarrying

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1910s

A man sits atop a pile of limestone blocks on a rail cart harnessed to a strong draught horse. The Quarry Park Interpretive Centre now stands just in the back.

Once the trees and soil were removed from the surface, work in the quarries encompassed a variety of activities depending on the desired product. If blocks of limestone were demanded, they would be cut by hand tools, shaped by stonemasons, and hauled to waiting train cars that would take them to their final destination.

To make crushed limestone and lime, dynamite would be dropped into plugs cut in the stone to burst them apart. The shattered bits of rock would be dropped in a massive crusher and sorted into pieces of varying sizes, depending on what the need might be. Other pieces would be dropped into kilns and exposed to raging flames that burned off the impurities and deposited white piles of lime at the bottom which was shovelled into wheelbarrows and delivered to waiting trains.

* * *

Identifying a suitable vein of limestone required a bit of guesswork, since most of it was hidden beneath the ground and only pierced the prairie soils in rare instances. Once a good deposit was identified, all overlying trees and soil were removed and the limestone exposed. Then the work could really begin.

The first quarries focused mostly on cutting limestone blocks to supply the construction boom underway in Winnipeg. Extracting these blocks was no easy matter, and the techniques used were virtually identical to those used by the Ancient Egyptians. Stonemasons would start by drilling a number of holes in the stone corresponding to the shape of block they wanted. Then two tools called feathers were inserted into each hole. A plug was inserted between each set of feathers and hammered down one at a time in sequence. The process continued and the plugs slowly wedged the feathers apart, until eventually a block would crack off.

These blocks could be small, like the blocks on the cart in the above photo, or they might weigh several tons. In either case teams of horses were absolutely indispensable for hauling, and in the quarries there was no shortage of work for teamsters, hostlers, and farriers (the people who take care of horses hooves and shoe them) .

By 1900, crushed limestone and lime had become much more important products from Stonewall's quarries, and it was much simpler to use sticks of dynamite to extract those materials than plugs and feathers.

The resulting rock shards were hauled to a giant crusher and dumped in, a job that was considered highly dangerous. A 1902 entry in the Quarry Diary illustrates the impressive impact these new machines made: "Winnipeg Contractors speak highly of the stone crusher by the enterprising firm of E. Williams and Co., of this town. The machine is supposed to crush one load per hour but is standing idle owing to a lack of men to work it. 'It is hoped that the great hungry monster may not get up some day in it's wrath and devour the whole town."1

The kilns we saw at the beginning of the tour were for the manufacturing of lime. Those particular blocky towers were draw-kilns, a design imported from America in 1895. They stood 12-15 metres tall and were themselves made of limestone blocks lined on the inside with fire-resistant bricks to prevent the buildings themselves from melting. The huge furnaces at the centre often burned day and night.

"Iron rods kept the rock up while heat melted it into lime, drawn out at the bottom. Every three hours or so, 25 or 30 wheelbarrows of lime were drawn and dumped into a box car lined with cold lime. The whole process took about 36 hours. Each kiln produced about 15 tons of lime per day. The lime was measured in bushels, a bushel weighing about 65 pounds."2

The men worked feverishly to shovel the lime and fuel the furnaces, and seem to have been quite competitive about it. An entry in the Quarry Diary from August 1899 lauds "Williams and Co's gang of 5 men loaded 15 bushels of lime in 7.5 hours. The gang who can beat this should be able to find employment."3

6. From Many Companies to One

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives NRC 24628

ca. 1900s

A crusher located in the centre of a quarry, alongside a crane that could lift rubble onto a conveyor belt that reached to the top. A railway boxcar can be seen just behind the crusher as well, awaiting a load of rubble. Most of the people in the photo appear to be dressed in their Sunday best, and a woman at the left even has a parasol, which might seem to indicate this is some kind of demonstration or public visit rather than a work day.

In this mid-1920s photo, we can already see several technologies that would not have been commonplace in the early quarry days in the 1880s, including the Guy Derrick crane design and the belt-fed crusher (not introduced until around 1900). Throughout the nearly 90 year operating life of Stonewall's quarries, technology continually evolved, greatly boosting efficiency but also requiring large investments that were often beyond the reach of the smaller quarry operators. These rising operating costs were one of the reasons the Winnipeg Fuel and Supply Company was able to gobble up the numerous small quarry companies operating around Stonewall, so that by the late 1920s it was the only company left standing.

* * *

Huge coal-powered machines like the rock crusher were introduced, enabling the mass production of crushed limestone. The 'Guy Derrick', the crane you see in this photo held aloft by dozens of steel cables, also came into general use at this time. It was capable of lifting 25 tons.1 From the 1910s, engines became vastly more efficient and more portable (powered by oil) and could be fit into vehicles like trucks, tractors, and excavators, which all began entering service in the quarries. Electricity could be used to power hand-held equipment like jackhammers that exponentially increased the amount of work a single man could do in a day.

Kilns also underwent a transformation. The first kiln design used in Stonewall was the 'periodic kiln'. Much smaller and simpler, lime could only be made in single batches and then the quarriers had to wait around for hours until the kiln cooled enough that the lime could be extracted. We will visit a surviving example of this style of kiln at stop 8 in this tour.

The draw-kilns, mentioned in stop 5 and seen at the beginning of this tour, were built between 1895 and 1917 and allowed continuous burning while lime could be continuously drawn out the bottom.

The cumulative effect of these new technologies was far-reaching. They allowed the quarries in Stonewall to dramatically increase their output and production shot up in the early 1900s, which also meant Stonewall's limestone deposits would run out that much faster. They also meant more work could be done by far fewer workers, meaning there were less jobs to be had. Automation, of course, remains a pressing concern today.

Finally, all these new machines were very expensive. In 1897 there were around ten companies operating quarries in Stonewall and each of them struggled to afford the technology that could drastically improve their profits. The solution? The companies started to merge. Winnipeg Fuel and Supply Co. was started in 1904 by a group of Toronto businessmen who saw the building boom in Manitoba and smelled an opportunity. They set up offices in Winnipeg to begin selling fuel (coal) and building materials (bricks, wood, limestone, and cement). Needing a nearby supply of limestone, they wasted no time in purchasing land in Stonewall and setting up their own quarry.

Their ruthless business instincts and advantage in Winnipeg retail outlets gave them an advantage over the small competitors established by some of Stonewall's pioneers. In 1910 they purchased the Patterson, Fullbrook, and Irwin quarries. The William and Gunn quarries amalgamated in 1916 to form Manitoba Quarries Limited, but they too were soon taken over. By 1927 Winnipeg Supply and Fuel Co. owned all the quarries in Stonewall.3 They would remain the only quarry operator in Stonewall until the last was shut in 1967.

7. Lives of the Workers

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1890s

This photo showing men shovelling shards of limestone by hand in wintertime shows just how hard this work was for those who toiled in the quarries. In the early 1900s, men like these worked 10 hour shifts, and those at the lime burners worked 12.1 As late as 1920 they were paid 34 cents an hour, low even by the standards of the time.2 Given the difficulty of the work, and the apparent lack of safety precautions we see in the photographs, there were relatively few on the job injuries or deaths.

Despite the low pay, these workers were welcomed into the community. In 1893, the community successfully raised funds to build a library and reading room for "the benefit of these strangers" arriving to work in the quarries.3 Many would set down roots in Stonewall, and are the ancestors of many of Stonewall's inhabitants today.

* * *

Canada's 1910 census showed those working in limestone quarries were the worst paid workers in any kind of mine, averaging an annual salary of about $609 (about $13,500 today). Those who worked on the lime kilns were paid a bit better, $838 a year ($18,700 today).5 However, they also worked 12 hour shifts instead of the 10 hours required of those doing the shovelling.

Those running the limestone quarries made more--but not enormously so. In 1920 F.J. Pearson was managing Winnipeg Fuel and Supply's Stonewall quarry operations, and he still only made $2,100 a year ($25,000).6 The quarries were not likely to be a career that would lead to great riches.

In addition to the long hours, strenuous conditions, and low pay, the labourers also had to contend with the physical dangers of the job. They were not nearly so deadly as working in an underground mine, but a number of injuries and some fatalities are recorded.

In 1926 the Quarry Diary records how "A sad accident occurred to Geo. Robert while working in the quarry one day last week, when a huge stone fell and pinned his foot. His cries of pain were heard by his fellow workmen, who rushed to his aid. It took eight men with crowbars to lift the stone high enough to free the unfortunate fellow."7 The use of dynamite for blasting was inherently dangers, and in 1895 several workers were seriously injured by a botched blast.8

Working in the limestone burners was not without its own peculiar hazards as well. Workers had to wear special clothing to protect their skin from exposure to the corrosive lime, and many likely suffered breathing ailments as a result. In 1950, one William Mollard died after falling from the top of one of the kilns while supervising the loading of limestone into it.9 William Mollard's brother Albert Josiah Mollard was killed in a crusher accident in the quarry in 1963. Albert had started working in the quarry in the 1920's and was just 2 months from retirement when he was killed.

There are other fatalities recorded at Stonewall's quarries in 1926, 1930, 1931, and 1932, and this is likely to be an incomplete record.10

Over time, the conditions in the quarries improved. The Canadian labour movement fought for and won nine hour work days. Pay improved, especially after World War II, and there was renewed attention to safety regulations.

One cause of these improvements was increasing automation of the work in the quarries. After World War II, excavators and dump trucks came to replace the shovelling labourers and horse-drawn teams that were commonplace. Fewer workers were needed to extract the same amount of limestone and lime, giving bosses more leeway to pay the few workers who remained better. By 1953, just 60 workers were on payroll, compared to the hundreds that had been needed a few decades before.11

Stonewall was changing.

8. Boom and Bust

ca. 1880s

Men stop and turn for a photo at the kilns situated on the northeast side of Quarry Park. Notice the black scorching on the bricks in the photo, which illustrates the great heat of the fires. This is a surviving example of the periodic kiln design, which was supplanted in 1895 by the more efficient draw kilns we saw at the beginning of the tour and will revisit again.

Throughout this tour, we’ve seen how technology and market conditions helped change Stonewall for the better - but just as we all know, that which goes up must come down. With the outbreak of the First World War, the residents of Stonewall discovered how closely their fortunes were tied to international events..

* * *

During this boom, Stonewall's limestone was used to build memorable facades across Winnipeg, such as in the Eaton Store and the Land Titles Building, and could be found further afield in grand buildings in Saskatchewan and Alberta. In 1903, the author of the Quarry Diary boasted "The demand for all kinds of building materials is very large in Manitoba. Let us be thankful the prospects for western Canada are so bright."2

Accounts from these times show Stonewall's quarry owners had an almost obsessive preoccupation with the availability of rolling stock (railway cars) to get their limestone to market. In 1902 a report the Quarry Diary griped that the Williams and Co. quarry had so "many orders in for rubble stone, but they inform us that cars are so scarce that it is almost impossible to fill orders the C.P.R. placed. What is the matter?"3

In most times, this is a good problem to have.

In 1911 Stonewallers could be forgiven for thinking the trajectory of uninterrupted growth would continue unabated. Yet these dreams would soon be shattered. It began with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Canada immediately mobilized for war. The construction boom fuelling limestone demand screeched to a halt, and orders for the quarries dried up, leading to layoffs. Tens of thousands of young Canadians rushed to enlist in the army, including many from Stonewall.

Of the many men from in and around Stonewall who went to France, 102 were killed and are commemorated on the local cenotaph.4 From a total population of around 1,000, this was a staggering blow to the little community.

Many of those who survived returned home with grievous physical and mental scars that they'd bear for the rest of their lives. They now had to find jobs in a struggling economy, which meant there was little demand for limestone or lime, and few jobs in the quarries. The recovery was slow, and it wasn't until 1924 that the author of the Quarry Diary could breathe a sigh of relief that orders for lime were finally coming in. "Glad to see the kilns burning again," they wrote.5

The recovery would be short-lived.

9. Twilight of the Quarries

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1940s

This is a great view of a busy working day at the lime kilns. The large wooden structure to the right is a rock crusher. Notice the man on the left kiln perched perilously atop the structure, getting a face-full of noxious smoke.

After the First World War, busy days in the quarries like this were increasingly rare. Battered by the Great Depression, another World War, and new competition from elsewhere in the country, the town's limestone business never regained the heights of the 1890s and 1900s. The crescent of quarries that formed a semi-circle around Stonewall shrank until only the one you are standing in now was left operating.

* * *

This pain was keenly felt in Stonewall, who no longer had anyone to sell their lime and limestone to. The first years of the 1930s were bleak, and thousands of unemployed crowded into cities like Winnipeg demanding government relief. Eventually the government relented and began commissioning make -work projects to give people jobs. Some of these required limestone and lime, and the government paid so-called 'relief workers' to work in Stonewall to get the quarries running again.1

The recovery was painfully slow, but slowly gathered steam. By 1936 the diarist of the quarries was thrilled to see three kilns operating at once, "which looks like the good old times. Many cars of lime are being shipped, business looks good."2

Nevertheless, this nostalgia couldn't hide the fact that the 1930s were still a pale shadow of the 'good old days.' A good indicator of the dislocation and stagnation caused by the First World War and Depression is Stonewall's population. In the 1941 census it was 1,025, almost exactly what it had been 30 years before.3

It was also around this time that the first generation of pioneers who set up quarries and put Stonewall on the map began to die out. The 1930s saw the passing of such enterprising individuals as Samuel Jackson, Stonewall's founder, John Gunn, who established the first professional quarry, F.J. Patterson and Fullbrook.4 The world was beginning to move on, and a new era in Stonewall's development was dawning.

10. The End of an Era

Stonewall Quarry Park Archives

ca. 1960s

For this stop, you can walk into the park to see Kinsmen Lake, which was reclaimed from the quarry and turned into a popular public park in 1956. After World War II, Stonewall's limestone deposits were nearing exhaustion and as time wore on the remaining quarrying operations were gradually scaled back, and then in 1967 the final quarry, the one we've been exploring, was shut down.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Stonewall's leaders successfully diversified the local economy away from the quarries, turning the town into a supply and service hub for the surrounding farmers. While Stonewall's quarry era had come to an end, it had laid the groundwork for a thriving town that has grown and persisted well beyond its original purpose.

* * *

There had once been a near continuous crescent of quarries on Stonewall's north and east boundaries, but by the 1960s most had already been repurposed and redeveloped into an industrial park and residential properties. That just left the quarry in which you stand. Part of it was given over to Kinsmen Lake in the 1950s, but for a long time there was no consensus over what to do with the rest. The quarries had played such a pivotal role in Stonewall's development, and many people saw value in preserving this one as a reminder of an earlier time.

In the 1980s a grassroots movement in Stonewall advocated turning this surviving quarry into a park. After much discussion, the Government of Manitoba agreed and established Stonewall Quarry Park in 1984. In 2011, the new Quarry Park Interpretive Centre opened to help explain to locals and visitors the importance of the quarries in Stonewall's history.

The distinctive kilns still stand, but are in dire need of repair to shore them up and prevent collapse. As symbolic of Stonewall's identity, efforts to fundraise to save the kilns are currently underway.

You can learn more about these efforts and how you can help at the Quarry Park Interpretive Centre.

Endnotes

1. 450 Million Years in the Making

1. Bilal Haq & Stephen Schutter. "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes." Science. Vol 322, Issue 589, pp. 64-68. Oct. 3, 2008.

2. National Geographic, "Ordovician Period and Facts." January 10, 2017.

3. Hobart King, "Limestone: What is Limestone and how is it used?" Geology.com.

4. The Winnipeg Tribune, "Geologists see historic places round Winnipeg," August 18, 1913. https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca

5. Mervin E. Farmer, Stonewall: Turning a Century 1878-1978, (Stonewall: Interlake Publishing Ltd, 1978), 10.

2. Why Limestone?

1. ScienceDaily, "Limestone," Sciencedaily.com.

2. King, "Limestone: What is Limestone and how is it used?" Geology.com.

3. Jared Diamond, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, (New York: Penguin Publishing, 2005), 169.

4. Farmer, 10.

3. Bridging Supply and Demand

1. Jim Silver, The Political Economy of Manitoba, (Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1991), 6.

2. Silver, 8.

3. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, (Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1984), 21.

4. The Quarriers

1. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, (Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1985), 8.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 10.

3. Canada. Fifth Census of Canada 1911: Religions, Origins, Birthplace, Citizenship, Literacy and Infirmities, By Provinces, Districts And Sub-Districts. Volume II. (Ottawa, 1913), 176.

5. The Art of Quarrying

1. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, (Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1984), 4.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 11.

3. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," (Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1984), 2.

6. From Many Companies to One

1. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 11.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 10.

3. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 10.

7. Lives of the Workers

1. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 15.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, 12.

3. The Winnipeg Tribune, "Stonewall Subscription for Reading Room," April 13, 1893, online.

4. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 10.

5. Canada. Fifth Census of Canada 1911: Forest, Fishery. Fur and Mineral Production. Volume V. (Ottawa, 1915), 23.

6. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, 12.

7. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 9.

8. The Prince Albert Times, "General News," April 23, 1895. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers=

9.Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 15.

10. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries, 10.

11. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 15.

8. Boom and Bust

1. Canada. Fifth Census of Canada 1911: Areas and Population by Provinces Districts and Subdistricts. Volume I. (Ottawa, 1912), 76.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 5.

3. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 4.

4. Manitoba Historical Society, "Historic Sites of Manitoba: Stonewall War Memorial," Online.

5. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 9.

9. Twilight of the Quarries

1. The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, "Quarry Worker Dies of Injuries at Stonewall," November 13, 1931, online.

2. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 11.

3. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 12.

4. Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries," 11.

10. The End of an Era

1. A Century of Hometown Service: Story of Winnipeg Supply, Winnipeg Supply and Fuel Company. (Winnipeg), 5.

Bibliography

Canada. Fifth Census of Canada 1911: Forest, Fishery. Fur and Mineral Production. Volume V. Ottawa, 1915.

Canada. Fifth Census of Canada 1911: Religions, Origins, Birthplace, Citizenship, Literacy and Infirmities, By Provinces, Districts And Sub-Districts. Volume II. Ottawa, 1913.

Diamond, Jared. Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin Publishing, 2005.

Farmer, Mervin E. Stonewall: Turning a Century 1878-1978. Stonewall: Interlake Publishing Ltd, 1978. https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A2376612#page/1/mode/2up

Haq, Bilal & Schutter, Stephen "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes." Science. Vol 322, Issue 589, pp. 64-68. Oct. 3, 2008. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/322/5898/64

King, Hobart. "Limestone: What is Limestone and how is it used?" Geology.com. https://geology.com/rocks/limestone.shtml

Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. The Stonewall Quarries. Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1985.

Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation. Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications. Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1984.

Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Recreation, Regional Museums Pilot Project Guidelines and Applications, "History of the Quarries." Winnipeg: Government of Manitoba, 1984.

Manitoba Historical Society, "Historic Sites of Manitoba: Stonewall War Memorial." http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/sites/stonewallwarmemorial.shtml

National Geographic. "Ordovician Period and Facts." January 10, 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/prehistoric-world/ordovician/

The Prince Albert Times, "General News," April 23, 1895. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/newspapers

The Winnipeg Evening Tribune, "Quarry Worker Dies of Injuries at Stonewall," November 13, 1931. https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/

The Winnipeg Tribune, "Geologists see historic places round Winnipeg," August 18, 1913. https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca

The Winnipeg Tribune, "Stonewall Subscription for Reading Room," April 13, 1893. https://digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca

Science Daily, "Limestone," Sciencedaily.com, https://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/limestone.htm

Silver, Jim. The Political Economy of Manitoba. Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1991.

Winnipeg Supply and Fuel Company. A Century of Hometown Service: Story of Winnipeg Supply.