Walking Tour

An Abuse of Power

Vernon's Internment Camp

Andrew Farris

Greater Vernon Museum and Archives

On the grounds of the W.L. Seaton High School there once stood an internment camp that imprisoned people who had committed no crime beyond being born in the wrong country. During the First World War hundreds of German and Austro-Hungarian citizens were held here against their will. Sometimes entire families were interned here for up to six years.

In this tour we will dive into the story of the Vernon internment camp. We'll see how Canadian society could turn on these people so rapidly, and how the government twisted itself into knots to find a proper legal justification for imprisoning people who had committed no crime. We'll learn about the conditions of life in this camp, and the fate of those who were dispatched to horrible construction camps in the mountains. We'll see how the prisoners came to cope with their circumstances, and how they resisted their mistreatment by the guards.

Route

This is a brief tour that winds around the grounds of Macdonald Park before returning to its original starting point. Macdonald Park is an operating school so it is advisable to take the tour outside of regular school hours.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Going to War

Greater Vernon Museum & Archives

1915-1920

Today Macdonald Park is used by the high school students of W.L. Seaton Secondary for various sport activities. But just over a century ago this was the Vernon Internment Camp.

It was here that hundreds of people, guilty of no crime save their nation of origin, were forcibly interned by the Canadian government. The only physical reminder of that chapter in Vernon's history is the plaque in front of you honouring the German, Ukrainians and other European internees who had been invited into this country with more or less open arms right up to the start of the war.

How could Canadian society have turned on them so quickly?

This is an important question that we will seek to understand in this tour. We will start by seeing how Canada even found itself embroiled in this European power struggle in the first place, the result of a baffling chain of events that would have incalculable consequences for the future of Canada and the whole world. As the military historian Gwynne Dyer writes, "There was probably not a single person in Canada in August 1914 (indeed, there were not even very many in Europe) who genuinely understood how the war had come about, but it made no difference."1

* * *

Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on July 28, and Russia, Serbia's traditional ally, stepped in to defend them. Germany was Austria-Hungary's ally and the greatest land power in Europe. They had just one war plan, the Schlieffen Plan, which involved attacking Russia and their ally France at the same time. So Germany went ahead and declared war on France as well as Russia, and activated the Schlieffen Plan. The plan also involved invading neutral Belgium.

Some historians have argued Great Britain could or even should have stayed out of the war, but the British had a treaty with Belgium, and they decided to honour it. On August 4 they declared war on Germany, and followed suit with Austria-Hungary on August 12 (with whom London had previously had quite good relations).2

This brings us to how Canada became involved. Canada was a Dominion of the British Empire at the time, a semi-autonomous colony that didn't have control over its own foreign affairs. As Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier said in 1910, "When Britain is at war, Canada is at war. There is no distinction."3

The vast majority of English-speaking Canadians agreed with this sentiment. "English Canadian popular culture was quite overtly militarist and jingoistic," Dyer writes. "The young had no doubts about the war; nor did most of their elders. In 1914 they were not just English Canadians; they were British Canadians."4

On August 4 spontaneous crowds gathered on the streets of most Canadian cities, creating scenes of patriotic fervour that would be difficult to comprehend today:

In Winnipeg, a Free Press representative brandishing a megaphone bellowed out the latest news; each announcement brought forth a full-throated roar from his audience. In Hamilton, when the Spectator projected stereopticon lantern slides of world leaders on its walls, pandemonium ensued... The wildly enthusiastic crowds that surged through Montreal's main thoroughfares sang "God Save the King," "La Marseillaise," "Rule Britannia," and "O Canada" in both languages.

[In Toronto] when the news appeared on the newspaper boards that Britain had declared war on Germany for invading neutral Belgium, the tension that had tightened during the previous days suddenly snapped and the crowds went crazy, flinging hats and umbrellas into the air with wild abandon.

Future prime minister John Diefenbaker was then a university student caught up in the hysteria. Writing later, he said it was hard to believe "that we entered the holocaust that was the First World War, if not exactly in ths spirit of a light opera, at least as if it were no more than the natural course of events."6

2. Canada Turns on the "Enemy Aliens"

Greater Vernon Museum and Archives 2500

ca. 1916

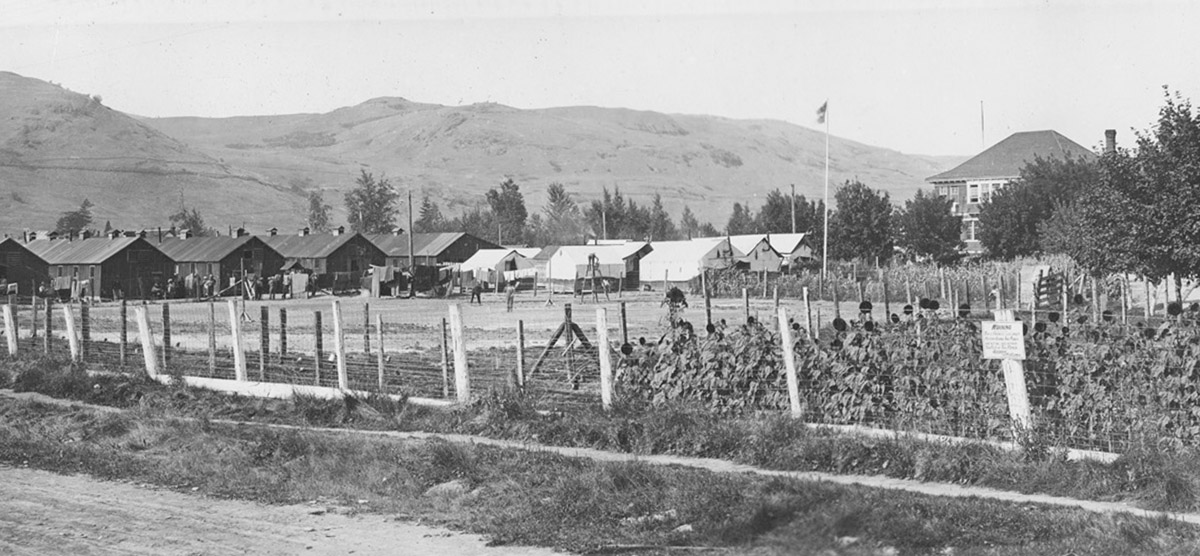

This photo of the camp gives us a small sense of how the camp operated. In the foreground is a vegetable garden, used to supply the camp with fresh produce. A row of wooden bunkhouses at the back of the photo housed the single male prisoners, while in front of these buildings on the left-hand side is a group of women tending to the laundry as it hangs on a clothesline.

In 1914 some cautioned against stereotyping the hundreds of thousands of people of German and Austro-Hungarian descent living in Canada as enemies, but a culture of fear and paranoia quickly spread. The government passed the War Measures Act, requiring everyone deemed an 'enemy alien' to register with the government. This was the start of a mass surveillance system of 88,000 people, few of whom had loyalties to any nation except Canada.1 Local authorities were given the latitude to round up any enemy aliens deemed a security risk and send them to one of the internment camps popping up around the country.

* * *

Let us not forget that at this distressing juncture there are many Germans in every Canadian community who should be treated with every consideration and with especial kindness. We have no hatred for the German people. They are blood-brothers of the Anglo-Saxon race. They are among the most estimable of our population.2

Prime Minister Robert Borden sought to reassure German-born citizens living in Canada, saying "that no one in this country... would for one moment desire to utter any word or use any expression in our debates... which would wound the self-respect or hurt the feelings of any man or woman in the country of German descent."3 It was noted that the Speaker of the House had German origins, and that Germans like him were "loyal subjects of his Majesty the King."4

Nevertheless wartime fear and paranoia were sweeping the country. Petty crimes, accidents, or apparently random acts of violence were attributed to enemy saboteurs and spies. A private guarding a canal in Quebec was shot and killed on August 28 by "an unseen assailant." Sentries were reportedly shot at or attacked in Calgary, Winnipeg, and Portage la Prairie. A bullet went through the window of a train carrying British officers near Sudbury.5 Rumours spread like wildfire, and they were fanned by an eager press.

Reports of the mass slaughter of civilians by the Kaiser's Army in neutral Belgium contributed to the growing rage (the reports were true, though exaggerated). In Canada the attitude towards Germans and Austro-Hungarians quickly darkened to one of suspicion and hostility.

Another issue were the many young men who had been trained as reservists for the German and Austro-Hungarian armies before coming to Canada, and were now being called home to fight for their fatherlands. The government wanted to prevent these men crossing the border to neutral America, and from there returning to Europe to fight.

These concerns motivated the government when they passed the War Measures Act later that month. The sweeping bill allowed the federal cabinet to rule by decrees known as Orders-in-Council, which bypassed parliament. The government now had the authority to censor and suppress communications, arrest and deport people without charge, and seize private property.

Along with other proclamations, the government officially designated anyone from an enemy nation as an "alien enemy," who would be required to register with the government, report monthly to the police, and swear an oath of allegiance to Canada. Failure to comply was grounds for internment.

A series of internment camps quickly sprang up across Canada, with the first opening in Montreal on August 13. The camp here at Vernon officially opened on September 18, 1914.

3. The Asylum

Greater Vernon Museum and Archives 2639

ca. 1912

This building was built in 1902 and briefly used as a provincial jail. By 1904 the Provincial Insane Asylum in New Westminster was overcrowded, and this building in Vernon was repurposed as an asylum, and many of the inmates in New Westminster were transferred here. The building was surrounded by gardens and a tree-lined boulevard.1

The asylum closed in 1912 and the building stood vacant until September 1914, when it became an internment camp. The initial trickle of internees turned into a flood but when the government expanded the criteria of who could be interned. Soon the old asylum building was overflowing, and in May 1915 the camp had to be expanded to the surrounding grounds. Bunkhouses, a mess hall, a guard room, and barbed wire stockade were built, so the camp could have a capacity of around 350.2

* * *

The second article reported that 11 alien enemy men arrested as prisoners of war in the Boundary district "who have attempted to leave the country to join the fighting line," were being transferred from Vernon's jail to the asylum that once stood here.4

Vernon was likely chosen for the internment camp because of the military base located nearby, which was headquarters of the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles. Over the course of the war it sometimes housed over 7,000 fighting men; the town of Vernon itself only had a population of 3,000.5 The base is still there today, but is mostly used as a Cadet Summer Training Centre.

The number of internees at the camp grew rapidly as more enemy aliens were apprehended, and the legal criteria for interning men was broadened and applied with increasing arbitrariness by local authorities.

At the time Canada was in a recession made worse by the outbreak of war and breakdown of world trade. There were thousands of jobless men across the country. Mass firings of enemy aliens by many employers meant the ranks of the destitute were joined by a growing number of Germans and Austro-Hungarians. The threadbare social safety net of the day left many of these men and their families at the brink of starvation. Local municipalities complained about having to provide for these people when their own resources were stretched so thin.

The government responded with an Order-in-Council on October 28. It said that enemy aliens who were unemployed could be interned, even if they were civilians and had been complying with all laws and regulations. It was "categorical in its instruction that enemy aliens who lacked the means to remain in the country were to be interned as PoWs and put to work."6 As the historian Bohdan Kordan explains, "The measure was deliberately open ended, giving officials the legal authority to intern any enemy alien."7

Determining who exactly met this definition was largely left up to local authorities. Many of them, especially in British Columbia, enthusiastically began rounding up the enemy aliens in their midst and dispatching them to Vernon.

4. Legal Acrobatics

Library and Archives Canada 4619805

1915-1920

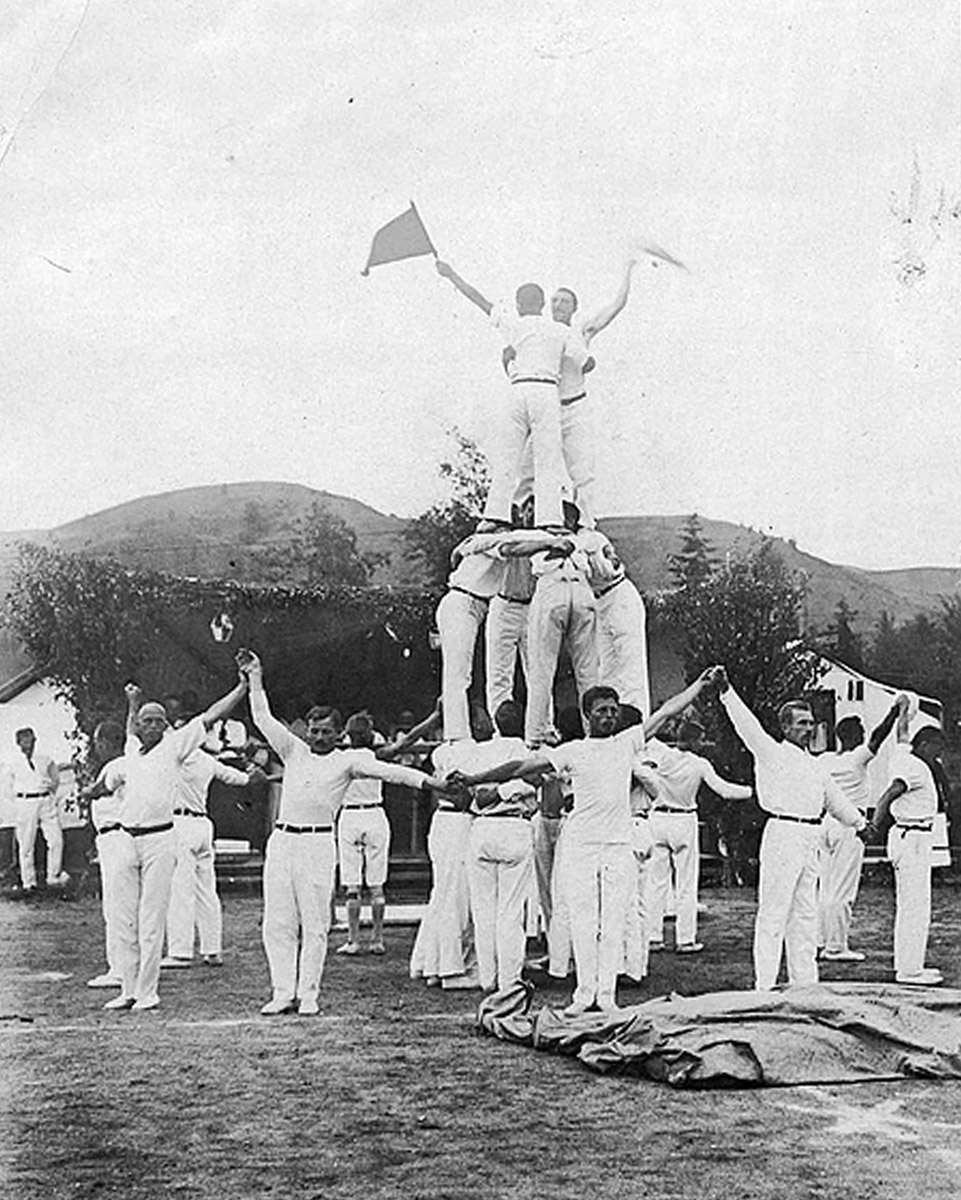

A group of internees put on an impressive acrobatic performance on the camp's parade ground. This was certainly one creative way for the prisoners to pass the time during their years of captivity.

The government itself was involved in a torturous set of legal acrobatics to legally justify the mass internment of civilians. While the Hague Convention stipulated that captured soldiers could be interned as Prisoners of War (POWs), but interning law-abiding civilians from an enemy nation without the right to a fair trial was quite illegal.

Furthermore, even if you accepted that these internees were POWs, then that meant the laws of war were supposed to apply to them. This was a problem for the Canadian government since they had no intention of following these laws in their treatment of the internees—they really wanted to make them do forced labour,, which was a violation of the laws of war. It took the justice ministry almost a year to cobble together a solution to this issue.

* * *

The Hague Convention of 1907 stated that POWs could be made to work to pay for their own captivity, so long as it wasn't in any job related to the war effort. They could not be coerced into working. They were also to be paid a similar amount to soldiers in their captors' army. Diplomats from neutral nations (in this case from Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States) were allowed to inspect and report back to the enemy country about the POWs' conditions.

Kordan writes that this whole legal regime only worked if "POWs recognized the authority of their captors and had submitted to them by laying down their arms.''1 For the enemy alien civilians who had immigrated to Canada, this was clearly not the case.

Could civilians who had committed no crime be arrested en masse as POWs?

This was an issue that had been "unforeseen" when the 1907 convention was drawn up.2 This is quite surprising since the mass internment of civilians had become quite common practice around that time. The Germans did it in modern-day Namibia, the Spanish in Cuba, and the Americans in the Philippines. Most famous of all the British had set up a massive internment camp system during the Boer War in South Africa. They'd rounded up tens of thousands of Afrikaaner civilians, mostly women and children, and put them into internment camps. Some 28,000 are thought to have died in the camps from disease, starvation, and neglect—including 22,000 children.3 Mass internment of civilians wasn't a novel concept in the British Empire.

Nevertheless, the Canadian government became acutely aware of its awkward legal situation when a judge presided over the case of two internees who tried to escape from a camp in Ontario. The judge ruled that they were "merely interned civilians," not POWs.

This was an alarming development for Major General William Otter, director of internment operations. If they weren't POWs then there was no legal justification for imprisoning them. He cabled the justice minister asking for guidance, saying he feared "we may be acting illegally." The ministry responded by more or less telling him to ignore the ruling. As far as the ministry of justice was concerned these internees were POWs because they'd been arrested for "military reasons."4

5. First and Second Class Prisoners

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-2194

ca. 1915

Internees playing hockey on the ice rink created on the grounds of the Vernon internment camp. Some of the men interned at this camp spent time reading up on international and Canadian law and lodged a number of legal complaints against their internment. These were invariably rebuffed by civil authorities.

This is actually quite surprising, given the justice ministry's preposterous legal position on internment. The ministry had realized they could call the internees POWs and ignore the laws of war at the same time: all they had to do was insist the internees were simultaneously POWs and enemy non-combatants. The laws of war didn't apply to noncombatants. They were going to have their cake and eat it too.

The historian Bohdan S. Kordan explains the result:

As POWs, they would work. But as non-combatants they were not entitled to protection under the laws of war. With no international legal framework to guarantee their rights, coercion would be used against those who resisted, either simply as a means of control or to extract labour. As the minister of the interior admitted in Parliament, this was the only way "we could get a lot of work done." The end result was that the internees were subjected to a strict work regime and a host of abuses.1

* * *

In the case of nearly all of us, we were deprived of our liberty for no other reason than just because we were Germans. [S]ince no proof of guilt was required against us, suspicion, however unfounded, sufficed. [I]t was a welcome for many, who owed us money, wanted our farms, or thought they had a grievance against us to denounce us as pro-German in order to escape the necessity of paying their debts or getting a cheap, but powerfully effective revenge for their supposed grievances.2

The government had solved one legal issue, only to have another one rear its head.

The German government was apprised of all these developments by neutral diplomats, and loudly protested any violations of the laws of war of German POWs in Canada. They threatened similar mistreatment of British citizens under their own control in response. The British government in London would not tolerate mistreatment of their citizens in German hands because of the misbehaviour of some administrators in faraway Canada.

This put the Canadian government in a tight spot. Germany would find out if they were abusing their internees, but Austria-Hungary on the other hand was a different matter. The Habsburg government only appeared to care about their citizens of German ethnicity. They took little interest in the treatment of their non-German citizens in Canada, like the Ukrainians, and other Europeans.

This was quite a convenient loophole for Canada, since the non-German prisoners had nobody to dispute their mistreatment, and there were a lot of them living in Canada. The government turned to the Hague Convention, which provided for classifying POWs as either first class (officers) who didn't have to work, or second class (enlisted men) who could work. The government simply classified all the German prisoners as first class prisoners and didn't make them work. The non-Germans were classified as second class POWs and enemy non-combatants and the government could do whatever it wanted with them.

At long last the government had fabricated a legal framework to imprison and then coerce any member of the many non-German nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (and later Ottoman Turkey and Bulgaria) and force them to do brutal labour under torturous conditions.

At the Vernon Camp the first and second class prisoners were separated into different quarters, with the first class prisoners getting better housing and living conditions, while the second class prisoners were kept in bunkhouses. For most second class prisoners, their stay in Vernon lasted until they were dispatched to road building projects at Mara Lake, Revelstoke, Monashee and Edgewood.

6. The German Prisoners

Library and Archives Canada 3218502

1915-1920

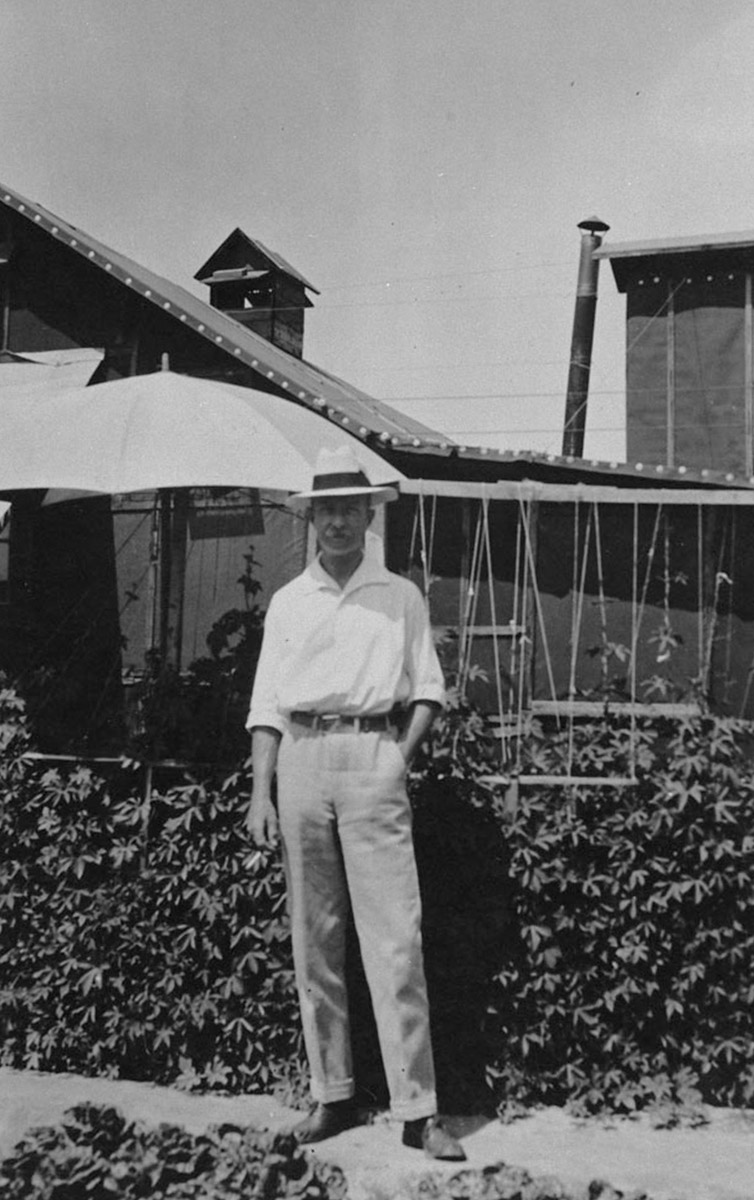

One of the German prisoners, Baron Rochus von Luttwitz, outside his cabin in the first-class prisoner compound. The small cabins could hold families and had their own vegetable patches that the internees could use to supplement their diet. These cabins afforded a measure of privacy to the internees and were a privilege afforded to the Germans due to their first class status.

The total camp population hovered around 350 for most of the war, but a total of around 1,100 prisoners passed through the gates of the camp between 1914 and 1920.1 2 Across Canada some 8,579 enemy aliens were interned during the war, but less than 20% of them were actually German—the rest were mostly Ukrainians. In the Vernon camp however these figures were reversed: around 75-80% of all the prisoners were German.3

Who were these German prisoners?

* * *

The next group of Germans to be interned were those unlucky enough to come under suspicion by a paranoid public, or run afoul of the regulations governing enemy aliens. In the tense wartime atmosphere their every action was carefully scrutizined by erstwhile friends, colleagues, and neighbours. An article in the Vernon News from that December cautioned the public against "sweeping accusations and rather bloodthirsty threats," towards enemy aliens, "as we hear too frequently has been the case." It noted that such accusations had already incited riots "in the bars and other public places of the city."4

The story of New Westminster's Otto Becker illustrates the precarious wartime existence of 'enemy aliens.' Many men like Becker did their utmost to prove their loyalty and play by the rules, but they were watched constantly by the police who eagerly awaited the slightest pretext to pounce.

In 1915 the Vancouver World reported that Becker, who was "rather a prominent figure locally," and owned his own wholesale coffee factory. He'd made "numerous and earnest efforts to be made a citizen of this country, but despite his utmost efforts… the application was invariably turned down."

The article baldly admits that the police had been trying and failing to find a reason to lock him up: "Becker has been under surveillance for some months, but seemingly the local authorities could never fasten anything to him." Finally in August the pretext came when he sold his coffee mill and allegedly wished to leave the country—if true, who can blame him? The immigration officials considered that sufficient cause for arrest. Becker spent the rest of the war in the internment camp here in Vernon.5

For all people of German origin, life in Canada during the war must have been a frightening and bewildering experience.

7. The Second Class Prisoners

1915-1920

Some men sit outside one of the bunkhouses in the second class compound. One is playing a guitar following along with the sheet music on the stand in front of him. It looks like a happy moment. The two compounds were separated by a gate, which was thought necessary because of the tensions between the German and non-German prisoners. Many non-German prisoners blamed the Germans for the war and their current predicament.

Most of the non-Germans held in the camp were mostly Ukrainains but there were also Croats, Serbians and Poles, among others. For the most part these men were interned not because they were considered a national security threat, but because they had been fired from their jobs and were living on the street.

These men usually only stayed in Vernon temporarily before being transferred to road-building camps in the mountains. As the economic situation changed by 1916, most of these men were paroled, meaning they were allowed out of the camp and could work for private businesses, though under heavy sanction. Only a relatively small number were kept in the camp until its closure in 1920, mostly men who indulged in ideas considered dangerous, like union organizing and political agitation.

The experiences of the non-German prisoners is covered in much greater detail in the Fernie, Morrissey, and Mara Lake tours.

* * *

As second class prisoners, these internees were now a pool of cheap labour. The BC government and Dominion Parks (forerunner of Parks Canada) made arrangements with the military authorities to put the prisoners to work on road-building and land-clearing projects across the province.

From 1915 prisoners were dispatched to build roads at Monashee and Edgewood, along Mara Lake just north of Vernon, at Morrissey just south of Fernie, at Field by Yoho National Park, and at Revelstoke National Park. The conditions at these camps were deplorable.

Economic interests dictated the way internees were treated; camp administrators were often pressured to ignore the laws that governed how POWs should be treated so that work would progress faster. Using picks, axes, shovels, and wheelbarrows, they cut roads across treacherous mountain passes in every kind of weather. Their food and clothing was wholly inadequate, and they were punished by abusive guards for any real or perceived insubordination. They were frequently beaten, jabbed with bayonets, and in some cases tortured.

In response the internees launched strikes and work stoppages which became more frequent as the conditions worsened. As we will see, this had an effect at the Vernon camp.

8. The Fate of Families

Library and Archives Canada 3379300

1914-1918

A woman stands between two files of first class cabins once located on this part of the field. Judging by the rather solid state of the cabins and the verdant creepers crawling up the walls, this must be later in the war or after the war, when the camp had become well established and some of the families had been there for four or five years. Most of the women and children in the camp were German, as "[i]t seems care was taken to keep German families together." There's evidence that such "care was not necessarily true for the Ukrainian families."1

We will return to the subject of the families of the German internees later on in this tour, but let's take a moment to consider the fate of the families of the Austro-Hungarian men.

Thousands of Austro-Hungarian men who entered captivity left behind wives and children outside the camp who were forced to fend for themselves. Many of these women, suddenly deprived of their menfolk, were also fired from their jobs for being 'alien enemies'. Only in rare cases was any provision made for these women and children. Poverty and starvation were the inevitable result.

* * *

A police officer investigated the home of Katie Fedych on Powell Street in Vancouver. The constable reported the house was in a "squalid" state, and found Fedych:

[S]obbing uncontrollably over the body of her six-month-old child. With her father interned at Morrissey and no food or money in the home, the baby had died of starvation. In broken English, the bereaved mother attempted to communicate her fear for her remaining four children.2

In another instance, Annie Dandys lived in the Crowsnest Pass with her three children. Her husband had been interned and sent to do forced labour at Morrissey. A police investigation found the entire family on the brink of starvation, the only food left being a bit of flour and coffee.3

The government was stingy about providing aid to any of these women. In both cases the police simply referred the distraught mothers to local charities.

Catherine Boychuk's case was particularly cruel. Impoverished after her husband's internment, she resorted to petty theft. When caught, she was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison. Her eight-month-old baby was sent to an orphanage and died eight days later.4

Asides from poverty, they also had to endure the humiliating stigma of being an 'enemy alien.' In 1917 a group of non-German 'enemy alien' women living in Calgary wrote an open letter to the women of the city, begging desperately for aid and understanding. The letter shows how bitterly they felt about their status, as they considered their own nations to be under an odious foreign occupation by the German-speaking Habsburg Monarchy.

We, the undersigned, Ukrainian and Austrian women, wish to bring before the notice of the women of Calgary and this province that our country was treated by the Austrian government 73 years ago as Belgium has been treated by the Germans. We came to this country to make Canada our future home. We are not spies. Thousands of our men are fighting under the British and Russian flags. We have been discharged from work because we are considered aliens, but we are loyal to Canada. What are we to do if we cannot get work? Are we to starve or are we to be driven to a life of vice? Will not the women of Calgary speak for us?

The Calgary Daily Herald reported that some of the city's prominent women had begun advocating for them "on the ground of humanity and the preservation of their woman-hood."

The Herald further noted that "In the majority of cases the ladies have found on investigation that they have no homes, bank accounts or sources of income whatsoever... If nothing can be done the delegation will ask to have the women interned."5

It is noteworthy that interning these women and children was seen as the most humane solution available.

9. Camp Life

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-2191

ca. 1915

This winter photo of the first class cabins camp shows the poor insulation the internees had during wintertime in the early years of internment. The daughter of one of the internees recalled how the housing in the camp developed over time: "Their place to stay was just a wooden floor with a tent pitched over it. Gradually boards were brought in and it became a shack. And the tent rotted, and ripped, and flew away--that sort of thing--as tents do."

Life in the Vernon camp was never easy. Though the internees weren't required to conduct hard labour while imprisoned here, 11 men still died at this camp. The food was substandard and insufficient, and the poor quality of housing contributed to outbreaks of disease. Despite their circumstances, some of the prisoners found time to escape the miseries of imprisonment through learning.

* * *

Meat rations in particular were reduced to cut the cost of internment. Major General Otter, the head of internment operations, estimated the daily food cost of a prisoner at exactly 28.368 cents per day (around $6.75 in today's money), but there was always pressure to cut costs.1 Anglo-Canadian citizens complained that these so-called "enemy aliens" were being fed too well when rationing had been introduced across the country and soldiers overseas were suffering.

This deprivation was particularly brutal on the men who were being forced to build roads. This was heavy manual labour, and they needed protein to recover after their exertions. Meat rations for these internees became so small that British Columbia's deputy minister for public works threatened to cancel the labour projects that internees were involved in "unless they were fed like human beings."2

Physical abuse was also common. Being deployed to guard ordinary citizens in the wilderness of BC's interior (instead of being sent to the front lines) was considered humiliating for soldiers. The soldiers and officers who were sent to Vernon grew resentful of their assignment and took it out on the internees. Vernon did not develop the horrifying reputation that other camps like Kapuskasing did, but this should not downplay the experiences of the internees here.3

Infections like pneumonia and tuberculosis thrive in damp, poorly insulated living quarters like those in Vernon. Large numbers of people crowded together in small spaces causes these infections to spread easily, especially when immune systems are weakened due to physical exhaustion and malnutrition.

Physical injuries and infections were not the only adverse health effects experienced by the internees, however; at least 106 people were institutionalized in mental health facilities. General Otter, the man charged with overseeing internment operations, admitted that for many, their symptoms were "brought about by the confinement and restrictions entailed."4 In addition to the horrific conditions they were subjected to inside the camps, many internees were terrified over the possible loss of their families back home: The Austro-Hungarian provinces of Galicia and Bukovina were on the front line of the First World War on the Eastern Front.

An October 1917 interim report from Vernon indicates that four men were receiving mental health treatment outside the camp at that time.5

After the armistice, some of the prisoners held in Vernon petitioned Arthur Meighen, the new justice minister, for their release. Meighen had claimed in the House of Commons that 54% of those who had been interned had become "insane." The petition asked Meighen what the reason for that might be, before offering their own suggestions: that the intense stress and anxiety of internment was too much anyone to tolerate and that continuous abuses by the guards compounded these stresses enormously.6 This "insanity" may have been what is now understood to be post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. We know now that PTSD leaves a long legacy, affecting a family even three or four generations later.

10. Passing the Time

Library and Archives Canada 4628431

1915-1918

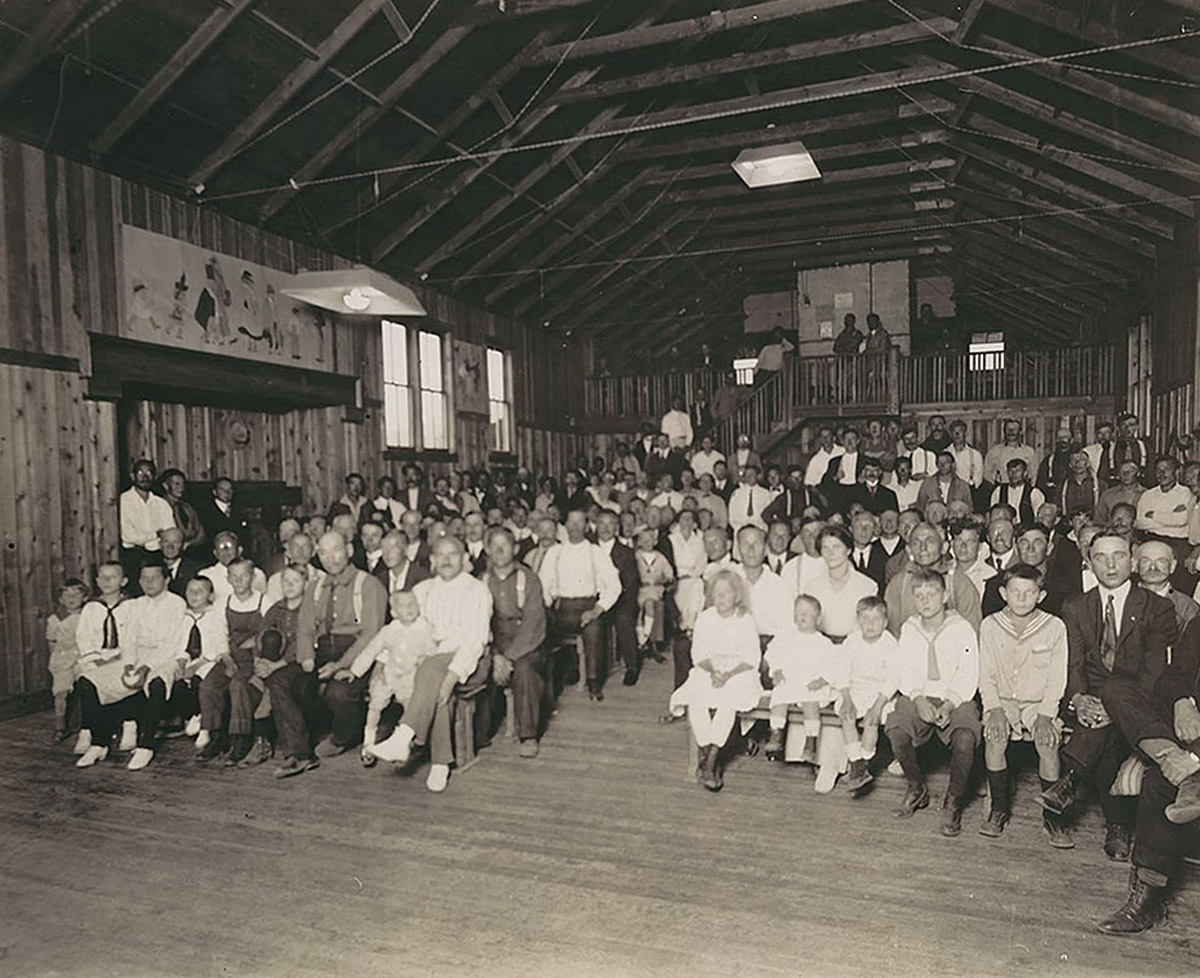

A rapt audience watches a motion picture in the YMCA recreation hall that was once located on this spot. The YMCA was allowed into the camps by the military authorities to organize recreational activities like putting on films, musical performances, and plays for the internees. The prisoners were expected to follow military discipline, but because at the Vernon camp they weren't expected to do much work, they had a lot of time on their hands.

They filled that time with physical activities like gardening and hockey, and more cerebral ones like self improvement through education. Some of the ideas spreading in the camp—socialism chief among them—were viewed as alarmingly subversive by the Canadian government.

* * *

Through the grinding years of boredom it was the exchange of ideas between prisoners that created the most interesting opportunities for leisure.

Gerald Kohse tells us about the many skills his parents had the opportunity to develop in the camp:

One of the things that my dad mentioned was in that camp you could run across people from every walk of life. If you wanted to learn how to speak Russian, there was somebody that could teach you Russian... If you wanted to learn how to brew beer, there was a person who knew how to do that there. My mother said that one of their close friends and neighbours was a man that had been a professional baker and he taught her how to bake bread. And she learned how to skate.1

Anne Sadelain, Vasyl Dosckoch's daughter, described the intellectual ferment Vasyl found in the Vernon internment camp:

My father found there were a lot of educated Germans there who had books and time for hobbies. The prisoners worked with wood, carving and building for recreation. He wasn't constantly harassed by his guards in Vernon, and so it was more free…

Very important for my father - he found the books that he could read and discuss with people. It was there that he first learned about Karl Marx and the Communist Manifesto. Another book that he brought from the camp and I still have it. It is called Socialism and the Ethics of Jesus. It was one of the first books he read when he was in the camp and he really treasured it. It was a time when ideas, socialist ideas, were taking hold in Canada too, although he certainly wasn't part of the Canadian fabric, being in that prison. But the ideas were getting to him too. He was a thinker and cared about those around him.2

Developments like this were extremely alarming to the Canadian government.

The world had changed dramatically since enthusiastic crowds had thronged city streets in August 1914. The war that was expected to be over by Christmas had gone on for years, consuming millions of lives in an endless meat grinder stalemate. Few understood why they were going to war in 1914. Fewer still understood in 1917—except by then many had been exposed to the previously undreamt of horrors of modern war.

By 1917 the war's insatiable demands for men and munitions had brought most of the war's major combatants to the brink of collapse. French soldiers, who had been ordered over the top on innumerable suicidal offensives, now marched into German guns literally bleating like sheep, knowing they were going to the slaughter. Soon nearly half of the French Army's divisions were mutinying. The Italian Army had crumbled under a combined Austrian and German offensive at Caporetto. Worst of all, the Russian Army had disintegrated entirely, and revolution had overthrown the Czar. The Bolshevik Party, promising Russia's peasantry "peace, land, and bread," seized power in the capital, Petrograd and exited the war. They then proclaimed history's first socialist state.

Canada too, was buckling under the strain. The Canadian Expeditionary Force was desperate to fill the gaps left in its ranks by the tens of thousands of dead and maimed, and in response the government introduced conscription. Francophone Quebec had little love for the British Empire and many there argued it was futile to send their sons to die in a pointless foreign war. Soldiers fired on anti-conscription rioters in Quebec City, killing 5. The Conscription Crisis of 1917 was the worst unity crisis in Canadian history, and very nearly brought about the breakup of Confederation.

Canada's government realized the real threat to the existing order wasn't enemy spies or saboteurs, but the overthrow of Canada's ruling class by a socialist revolution that wanted to end the war, whatever the cost.

The growing fear of socialism prompted the internment authorities to look at the remaining internees in a harsh new light.

11. Interning Women and Children

1915-1920

This photograph shows Fred Kohse and his cousin Victor Heiny as toddlers inside the Vernon internment camp. Fred stands on the left holding a branch almost as tall as he is, and Victor is on the right. Just beside Victor you can make out a stretch of the barbed wire fence that forced these little boys to remain inside the camp.

The military authorities allowed women along with their children to voluntarily enter internment with their husbands. At Vernon they were kept in a "prisoners village" separate from the rest of the camp quarters. The conditions for these families were far better than those faced by the interned men doing road work on mountainsides, but they were still deprived of freedom and spent years languishing in boredom behind barbed wire.

Over the course of the war some 24 children were interned alongside their parents at the Vernon Camp. Some of them knew of no other life before their release; three babies were born in the camp.1

* * *

The women who were interned in the camp were expected to carry out a staggering amount of work. They cleaned the buildings of the camp and maintained the gardens that provided food for the internees. Women were responsible for caring and educating children, hauling water, and bringing in wood for the fire.

The case of Fanny Priester shows that once a woman was interned, she was not simply free to leave, even if her relationship with the internee broke down. In a rather curious situation, Priester, a German, was hired by several of the German male internees as a cook and cleaner. She was allowed to live in the camp and assigned a POW #5003, though she wasn't technically an internee, nor did the government have any grounds to intern her.

Following a dispute with her employers and another cook, Priester wrote to Major General Otter requesting release. 'I am a girl and have nothing to do with the war…" she wrote. "[I have] never had the slightest idea of harming anybody and don't see how I could."

Otter refused on the absurd grounds that Priester was a security threat—her time in captivity meant she knew the layout and operations of the camp too well. He also pointed out that public opinion in British Columbia was strongly opposed to releasing any enemy aliens—even women.

Priester appealed directly to the justice minister. Otter continued to object fiercely: "I have personally seen the woman, who is decidedly German, young, and to my mind a cunning, determined type... she is now well housed as others of her class, and therefore has no cause for complaint on that score." After eight months the minister overruled the general and approved Priester's release.2

Along with the men, many women and children continued to be held in the camp for years after the war ended. In July 1919 there were still 139 inmates at the Vernon Camp, including 20 women and 24 children.3

Gerald Kohse, Hilda's son born after internment, recounts how his family's internment ended:

One day, after the war ended, Mother was out with friends in the compound in the Vernon camp. This lady on the other side of the fence was playing tennis. She tossed a ball over the fence to my mother and my mother picked it up and there was a note in it. Mother read it and scribbled something on the note and threw it back. And they developed a, you might say, a friendship, by tossing notes over the fence.

The war had been over for more than a year and… it seemed… that the internees were going to be there forever. So she wrote a letter to the minister of justice wanting to know why they were still in jail when the soldiers had gone home—the war was over. It was 1920. She rolled the letter up and put it in the tennis ball and tossed it over the fence. Then she asked this lady if she would mail it for her… I guess that lady on the outside did mail it because apparently when they were released the guy that did the office, snarled at her, "How did you get that letter out?"4

After their release, Fred and his family moved to the northern part of Vancouver Island. Fred spent sixty years in the fishing industry as a fisherman and a troller captain. He returned to Vernon briefly in 1997 to attend the unveiling of the memorial plaque we saw at the entrance to this park. He never forgot the first six years of his life spent behind the barbed wire that surrounded this field.

12. Resistance

Greater Vernon Museum and Archives 16123

1915-1920

A lone soldier stands guard by the barbed wire ringing the internment compound. A total of 107 internees died in captivity in Canada during the First World War. Six of these were men shot trying to escape.

The conditions at the Vernon internment camp were generally much better than those of the road construction camps in the mountains, but they were by no means pleasant. It was humiliating and boring, and they were deprived of most of life's pleasures and opportunities.

The conditions inspired many acts of resistance, the most spectacular of which was escape. In Vernon the endless monotony of camp life and the high proportion of first-class German prisoners not forced to work meant there was ample time to plot intricate and ingenious escape attempts.

Since this camp was also the main hub for all the other camps in British Columbia, many second-class prisoners were rotated in and out of Vernon from the road-building camps, and shared their nightmarish experiences with those interned here. The Vernon prisoners took it upon themselves to advocate for their comrades toiling in the mountains, writing to neutral diplomats and pursuing all available legal means to have the abuses put to an end.

* * *

The most dramatic escape attempt came in September 1916. Gwen Cash, a former reporter for the Vancouver Province, described what happened:

Under the leadership of a young civil engineer, the prisoners tunnelled from under the dining-room of the second-class prisoners. They used, we found afterwards, to carry loose dirt out in their pockets and put it down the holes in the floors of their shacks. The tunnel was about sixty yards long--went way under the barbed wire and ditches, which in summer were dry. One dark night the engineer leading the way escaped, but the second man, fat anyway, tried to take too much dunnage with him, dislodged some dust and sneezed. He, with eight others, was caught in the tunnel.3

Contemporaneous newspaper reports claimed the entire 30th BC Horse Regiment—several thousand men—was sent to scour the hills for the engineer. A man was arrested and accused of being an accomplice because he apparently had escape cars waiting at the other end of the tunnel. According to the Vancouver World, the accomplice had been a former internee in the camp, but was released because "he produced papers showing that he had come from Russia." The investigation revealed a most damning revelation about this man however: according to the World, "It is said, however, that while he lived in Russia, he is in reality a German."4

Afterwards Cash says that all the camp buildings were raised on pilings to prevent another tunnelling attempt, "but the prisoners, ever hopeful, started another [tunnel]. This time the authorities knew all about it from the beginning. Used to in fact go along it and inspect its progress. The prisoners were furious when, in the course of time, they found they had been allowed to dig to 'keep them happy.'"5

The prisoners in Vernon also fought for the rights of their fellow prisoners in the road-building camps. Internees at Morrissey, Monashee, Field, and Edgewood all reported violent physical abuse at the hands of captors who forced them to work in intolerable conditions. Work stoppages and strikes became common as the internees fought to maintain a shred of their own dignity. The military authorities responded with either harsher measures, closing down the camps entirely and starting over elsewhere, or trying to remove any ringleaders from the group. In the latter cases those ringleaders were usually sent to Vernon.

Vasyl Doskoch, an Ukrainian in his early 20s, had been forced to work at Mara Lake, and later Morrissey. In early 1918 he was transferred to Vernon. Doskoch was the first of six signers of an impassioned letter to the Swedish consul on behalf of their fellow prisoners who remained at Morrissey. The letter reads:

We beg to inform you that our fellow Prisoners in Internment Camp at Morrissey are exposed to the very brutal treatment of the Canadian soldiers and non-commissioned officers doing police duty there. As we know that it is impossible for them to write to you stating the facts, and that complaints to the Officer Commanding at Morrissey results only in making things worse for them, we must request you, for the sake of humanity, to inform the Royal Consulate of Sweden, the legal Representative of our Interest in Canada, of these conditions and to beg him to exercise have a stop to the cruel treatment of Prisoners of War in Morrissey.6

13. The End of Internment

Greater Vernon Museum and Archives 21289

1915-1920

We've returned to the entrance of the camp, showing an official vehicle carrying military officers departing the camp as guards stand at attention.

The Vernon internment camp stayed open long after the war, as the internment authorities spent years making arrangements to deport the last prisoners. When it finally closed in 1920 the buildings were dismantled and eventually the grounds turned over from the provincial government to the City of Vernon, where it became a children's playground. Ultimately the W.L. Seaton High School was built here. The dark chapter of internment faded into Vernon's history. It is only through the efforts of many dedicated historians, descendants of internees, and organizations like the Vernon Family History Society, and the Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund, that the story can now be told in such detail.

* * *

Throughout 1917 and 1918, many prisoners were paroled into industries that were experiencing labour shortages. The men in Vernon were paroled in the eastern provinces rather than being released locally due to public pressure. Those who were considered difficult, infirm, or were experiencing mental health challenges remained interned.

In November 1918, General Otter requested that all of the internment camps that remained open send him a list of internees that were considered 'undesirable.' This was done with the idea of deportation in mind. The commandant of the Vernon camp declared only 86 of the prisoners there to be well-behaved. The others he found 'undesirable' on a variety of grounds. Some he felt were pro-German or pro-Austrian; others were viewed as bitter towards Canada or Britain, and the remainder he considered "feeble", "insane", or "decidedly eccentric."1

Otter arranged for the deportation of 200 unmarried men who were interned in Vernon and determined to be a threat. After this first wave of deportations, 20 women and 24 children were among those who remained imprisoned in Vernon. Otter hoped to deport all of them as he believed that the women were "'as a rule even more disloyal than the husbands.'"2

The camp finally closed on February 20, 1920. It was the second-to-last camp to do so. The released internees were forced to start their lives over. The government had seized their assets and rarely if ever returned them. The internees who remained in Canada were dispossessed and permanently affected by their experiences.

In 1992, an accounting firm produced a report estimating that the economic losses suffered by internees could be valued between $21.6 and $32.5 million (between $36.9 and $55.5 million today).

Efforts to have Canada's first national internment operations recognized began in 1978 when Nick Sakaliuk gave testimony to historians about his experiences as an internee. Mary Manko Haskett, Honorary Chair of the Redress Campaign was instrumental to the movement's recognition. She was one of the children interned in the camps and her younger sister, Nellie, died during internment.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

1. Going to War

1. Gwynne Dyer, Canada in the Great Power Game 1914-2014, (Toronto: Random House Press, 2014), 55.

2. R.F. Bridge, "The British Declaration of War on Austria-Hungary in 1914," The Slavonic and East European Review Vol. 47, No. 109 (July 1969), pp.401-422, 409.

3. Canadian War Museum, "Canada at War," warmuseum.ca, online.

4. Dyer, 56.

5. Pierre Berton, Marching as to War: Canada's Turbulent Years 1901-1953, (Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada, 2002), 130-131.

6. Berton, 133.

2. Canada Turns on the "Enemy Aliens"

1. Al Hiebert, "Ukrainian-Canadians and the Vernon Internment Camp of WW1," in The Sixty-Sixth Report of the Okanagan Historical Society (Kelowna: Okanagan Historical Society, 2002), 24.

2. Vernon News, "Our German Friends," August 20, 1914, online.

3. Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience, (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 26.

4. Semchuk, 3.

5. Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience, 12-13.

3. The Asylum

1. Darren Handschuh, "Hospital for the Insane," Castanet News, Jan 12, 2020, online.

2. Hiebert, 26.

3. Vernon News, "Special Notice to Alien Enemies," September 17, 1914, online.

4. Vernon News, "Eleven Prisoners of War Brought to Vernon," September 17, 1914, online.

5. Vernon Cadet Museum, "Vernon Military Camp," vernoncadetmuseum.com, online.

6. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," Canadian Military History 29, no. 2 (2020): 1-28, 6.

7. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 12.

4. Legal Acrobatics

1. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 14.

2. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 9.

3. Paul Harris, "'Spin' on Boer Atrocities, The Guardian, December 9, 2001, online.

4. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 25-26.

5. First and Second Class Prisoners

1. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 26.

2. Kordan, "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," 25-26.

6. The German Prisoners

1. Hiebert, 26.

2. Vernon Museum & Archives, "The Vernon Internment Camp," vernonmuseum.ca, September 17, 2021, online.

3. Hiebert, 26.

4. Vernon News, "Alien Residents," December 17, 1914, online.

5. Vancouver World, "German is Arrested," August 6, 1915, online.

7. The Second Class Prisoners

1. Luciuk Lubomyr, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920. (Kashtan Press, 2001), 86.

8. The Fate of Families

1. Hiebert, 26.

2. Kordan, No Free Man, 166.

3. Kordan, No Free Man, 166.

4. Semchuk, 17..

5. Semchuk, 17-18.

9. Camp Life

1. Hiebert, 27.

2. J. Griffith, BC Deputy Minister of Public Works, to Lieutenant-Colonel W. Ridgway-Wilson, BC Dept. of Alien Reservists, 1 February 1916, RG 13 A2, vol. 1929, file 10/1917, LAC cited in Kordan, "Internment in Canada," 20.

3. Kordan, "Internment in Canada," 18; Kordan, No Free Man, 170.

4. Hiebert, 27-28.

5. Hiebert, 27-28.

6. Kordan, No Free Man, 249.

10. Passing the Time

1. Semchuk, 143.

2. Semchuk, 117.

11. Interning Women and Children

1. Semchuk, 17.

2. Kordan, No Free Man, 169.

3. Kordan, No Free Man, 255.

4. Semchuk, 144.

12. Resistance

1. Vernon News, "Three Germans Escape from Internment Camp," April 1, 1915, online.

2. Vernon News, "German Prisoner Escapes from Vernon, April 6, 1916, online.

3. Semchuk, 12.

4. Vancouver World, "Germans Escape Through Tunnel, September 16, 1916, online.

5. Semchuk, 12.

6. Semchuk, 116.

13. The End of Internment

1. Kordan, No Free Man, 236.

2. Kordan, No Free Man, 250, 253.

Bibliography

Berton, Pierre. Marching as to War: Canada's Turbulent Years 1901-1953. Toronto: Penguin Randomhouse Canada, 2002.

Canadian War Museum, "Canada at War," warmuseum.ca. https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/history/going-to-war/canada-enters-the-war/canada-at-war/

Dyer, Gwynne. Canada in the Great Power Game 1914-2014. Toronto: Random House Press, 2014.

Hiebert, Al. "Ukrainian-Canadians and the Vernon Internment Camp of WW1." In The Sixty-Sixth Report of the Okanagan Historical Society, 19-34. Kelowna: Okanagan Historical Society, 2002.

Kordan, Bohdan S. "First World War Internment in Canada: Enemy Aliens and the Blurring of the Military/Civilian Distinction," Canadian Military History 29, no. 2 (2020): 1-28.

Kordan, Bohdan S. No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Lubomyr, Luciuk. In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1920. Kashtan Press, 2001.

Semchuk, Sandra. The Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019.

Vernon Cadet Museum. "Vernon Military Camp." https://www.vernoncadetmuseum.com/history-vernon-military-camp.html

**Newspaper Articles**

"Alien Residents." Vernon News. December 17, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1914-12-17-VN-Alien-Residents.pdf

"Eleven Prisoners of War Brought to Vernon." Vernon News. September 17, 1914, online. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1914-09-17-VN-Eleven-Prisoners-of-War-Brought-to-Vernon.pdf

"German is Arrested." Vancouver World. August 6, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1915-08-06-VW-German-is-Arrested.pdf

"Germans Escape Through Tunnel." Vancouver World. September 16, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1916-09-16-VW-Germans-Escape-through-Tunnel.pdf

"German Prisoner Escapes from Vernon." Vernon News. April 6, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1916-04-06-VN-German-Prisoner-Escapes-from-Vernon.pdf

Handschuh, Darren. "Hospital for the Insane." Castanet News. Jan 12, 2020. https://www.castanet.net/news/Vernon/274435/Vernon-once-had-a-hospital-for-people-who-were-thought-insane

Harris, Paul. "'Spin' on Boer Atrocities." The Guardian. December 9, 2001. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/dec/09/paulharris.theobserver

"Our German Friends." Vernon News. August 20, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1914-08-20-VN-Our-German-Friends.pdf

"Three Germans Escape from Internment Camp." Vernon News. April 1, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1915-04-01-VN-Three-Germans-Escape-from-Internment-Camp.pdf

"Special Notice to Alien Enemies." Vernon News. September 17, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1914-09-17-VN-Special-Notes-to-Alien-Enemies.pd