Partner City

Saskatoon

City of Bridges

In 1883 a group of Toronto-based Temperance Colonization Society methodists established Saskatoon on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River. They aimed to build a society free from the scourge of alcohol. The colony grew only very slowly, even after it was reached by a railway in 1890. In 1901, almost 20 years after its founding, Saskatoon's population was still only 113. Saskatoon's first big break came in 1903, when a huge party of colonists from Britain, led by the Reverend Isaac Barr, began settling west of Saskatoon, but the enterprise was so chaotic and poorly planned that many of the colonists ended up settling in and around Saskatoon, especially on the west bank of the river where some established the village of Nutana. The second break came in 1904, when Saskatoon was designated the divisional centre for the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, which put Saskatoon right in the middle of prairie development. The population boomed, and by 1906 had skyrocketed to 4,500. The third boost came after Saskatchewan became a province in 1905, when Saskatoon was chosen as the site of the University of Saskatchewan. It grew rapidly until 1913 when growth across all Western Canada shuddered to a halt. In the following decades, Saskatoon went through booms and busts, and the Great Depression hit the city especially hard. After the Second World War however the city benefited from the economic trends that were bouying much of Western Canada, and it has continued to grow to this day. Now it is the largest city in Saskatchewan and its main economic centre.

We respectfully acknowledge that Saskatoon is on Treaty 6 territory, the traditional territory of Cree Peoples, and the homeland of the Métis Nation.

Tours

Explore

Saskatoon

Stories

Eaton Internment Camp

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Assoc.

Story Location

The Eaton internment camp was one of 24 internment camps set up in Canada for enemy aliens during and immediately after the First World War. It was the only camp in Saskatchewan, and was an extremely rudimentary facility, with the 65 internees quartered in unheated boxcars on the Eaton railway siding at the height of the Saskatchewan winter.

* * *

Starting in 1914, the Canadian government reclassified all immigrants from enemy nations as "enemy aliens," a status that stripped them of virtually all their civil rights. Any who were suspected of disloyalty were interned, along with enemy aliens who were homeless. The majority of those interned were poor Ukrainian men who had immigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most were sent to remote forced labour camps. By 1916 the wartime labour shortage led the government to begin paroling all the "non-dangerous" internees to work in strategic industries.

Most of the remaining internees were deemed "undesirable" and kept interned until 1920, when they were deported. The "undesirables" were generally men who had alleged sympathies with Canada's enemies, had been uncooperative while being forced to do back breaking labour, or thought to be lazy. As one camp commandant said, they were "a loafing, good-for-nothing lot, and the sooner the country is rid of them the better."1

In addition, from 1917 to 1920, during Canada's first Red Scare, an increasing number of socialists and labour activists were arrested and interned.

The internees sent to Eaton were those unfortunate "undesirables". They were sent to Eaton Siding to do forced labour building railway tracks in the depths of the Saskatchewan winter. They arrived here on February 25, 1919. It was three months after the war had ended. They had come from a railway building camp in Munson, Alberta, which had become untenable as the deadly 1918 Influenza Pandemic swept through the camp, and many internees were stricken, refused to work, or escaped.

Moving 65 of Munson's internees to Eaton was meant to alleviate overcrowding and hopefully make them amenable to doing forced labour. The conditions at Eaton can hardly be said to have been an improvement: the internees were kept in freezing boxcars and expected to do back-breaking railway labour in deep drifts of snow with inadequate winter clothing.

Immediately, at least two internees escaped after subduing a guard. There were likely more escapes, though records from this camp are sketchy. The internees resisted their guards and the demands to work. As a result the government gave up on the Eaton camp, and decided to send them to the more permanent facility at Amherst, Nova Scotia, where they could await deportation.

The camp was dismantled on March 21, 1919. It was only open for 24 days, making it the shortest-lived of the 24 internment stations. The fate of the internees is unknown, though most were probably deported.

The camp's location was forgotten for over 70 years. To avoid confusion with the Saskatchewan village of Eatonia, Eaton Siding was renamed Hawking in 1925, making tracking down the site more difficult for researchers. It wasn't until the 1990s that Bohdan S. Kordan, a University of Saskatchewan professor and prolific writer on Canada's First World War Internment Operations, was able to positively identify the camp's original site. It just so happened to be on the grounds of the Saskatchewan Railway Museum.2

In 2005 the University of Saskatchewan's Prairie Centre for the Study of Ukrainian Heritage partnered with the Saskatchewan Railway Museum to unveil a monument and memorial garden on the museum grounds. The monument entitled "Fortitude," was sculpted by local artist Grant McConnell, and depicts an internee at work laying railway ties, watched over by an armed guard.3

Today, visitors to the Saskatchewan Railway Museum can take tours of boxcars like those that the internees were housed in.

2. "The Camps - Eaton," Armistice Films, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5eGYvty3VZM.

3. "Fortitude memorial in Eaton Internment Camp Site," Ukrainian Places.com, *https://www.ukrainianplaces.com/node/2097.

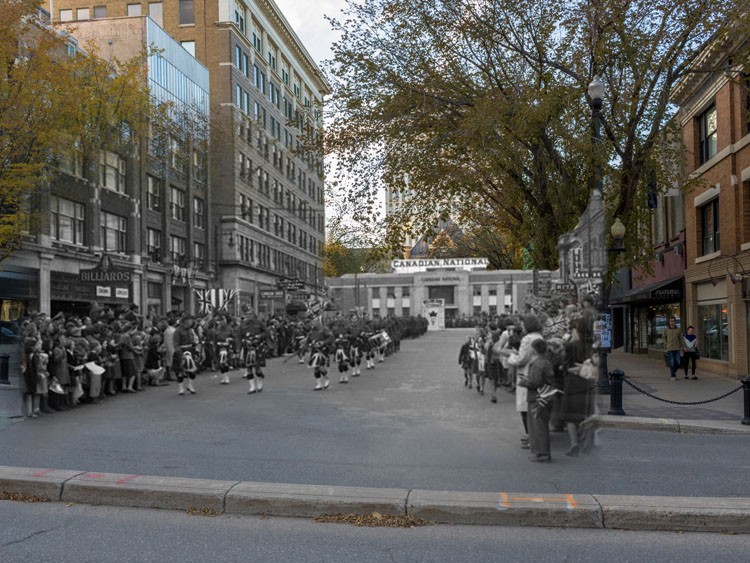

Then and Now Photos

C Troop of the NWMP

Saskatoon Public Library LH-1933

1887

This pictures shows the Royal Northwest Mounted Police of "C" troop of the Battleford post, ready to depart after visiting "F" troop in Saskatoon. This house, built in 1883, was rented by the NWMP for the barracks of the first police post in Saskatoon in 1886.

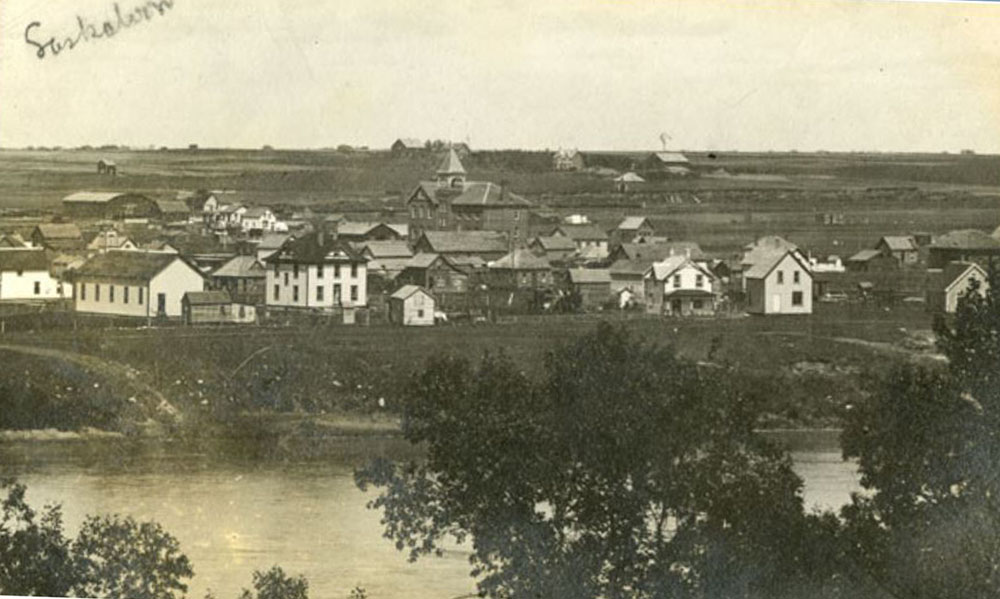

A View of Downtown

Saskatoon Public Library LH-728

1905

A view of downtown Saskatoon and the first King Edward School, which became a temporary site for City Hall after 8 years of operation.

Trestles

Saskatoon Public Library LH-31

1905

Wooden trestle bridges, like Saskatoon's original Traffic Bridge, were the backbone of the westward expansion of the railway. While the majority of rail technology in the 1800s was developed in Europe, the North American west lead innovation in the development of the towering trestle bridges. The average bridge was 12 - 15 stories high, and relied on the seemingly unending forests of timber in the west. Construction of these bridges depended on the forests, but their installation was key in accessing them. Saskatoon's Traffic Bridge stood until 2010, when severe structural deterioration necessitated its closure for safety of the public. Crowds gathered along the banks of the South Saskatchewan in 2016 to watch as crews destroyed the old bridge with strategic explosions. The new, modern steel truss bridge opened to accommodate the increased volume of 21st century traffic in 2018.

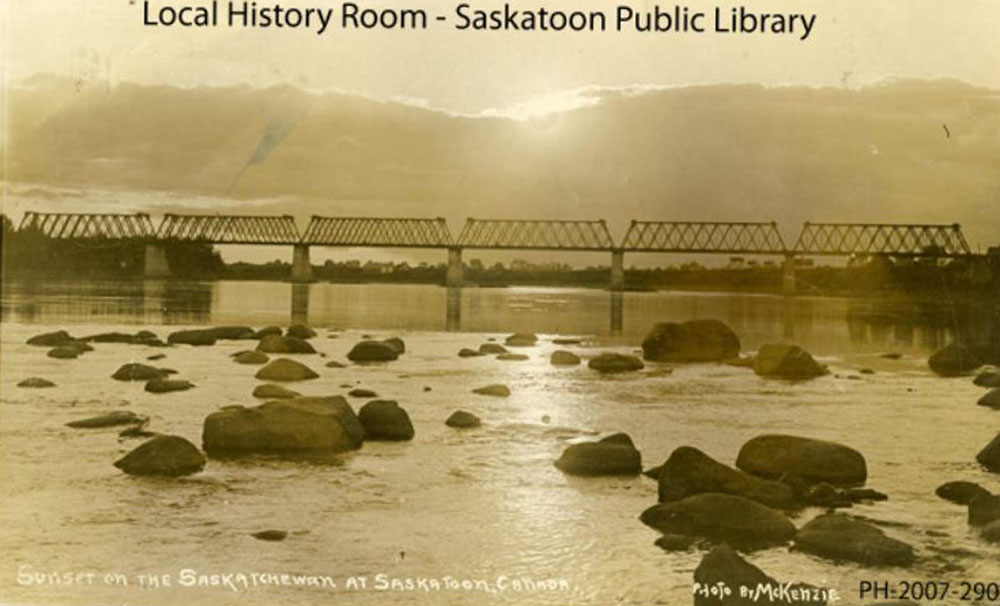

The Best Sunsets

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2007-290

1910

One of the best things about Saskatoon, and the prairies overall, is the stark and uninterrupted beauty of the landscape. This photo of a sunset over Traffic Bridge has a golden hue, even in black and white. British Columbians has their ocean and mountain views, the Yukon has dancing Aurora over a field of white snow, and the Maritimes have their quaint fishing villages, but any Saskatonian will tell you; the prairies have the best sunsets. Walt Whitman, the illustrious American poet, wrote about prairie sunsets in beautiful, sweeping language that any visitor to the prairies can relate to.

Shot gold, maroon and violet, dazzling silver,

emerald, fawn,

The earth's whole amplitude and nature's mul-

tiform power consigned for once to colors;

The light, the genial air possessed by them—

colors till now unknown,

No limit, confine—not the Western sky alone—

the high meridian—North, South, all,

Pure luminous color fighting the silent shadows

to the last.

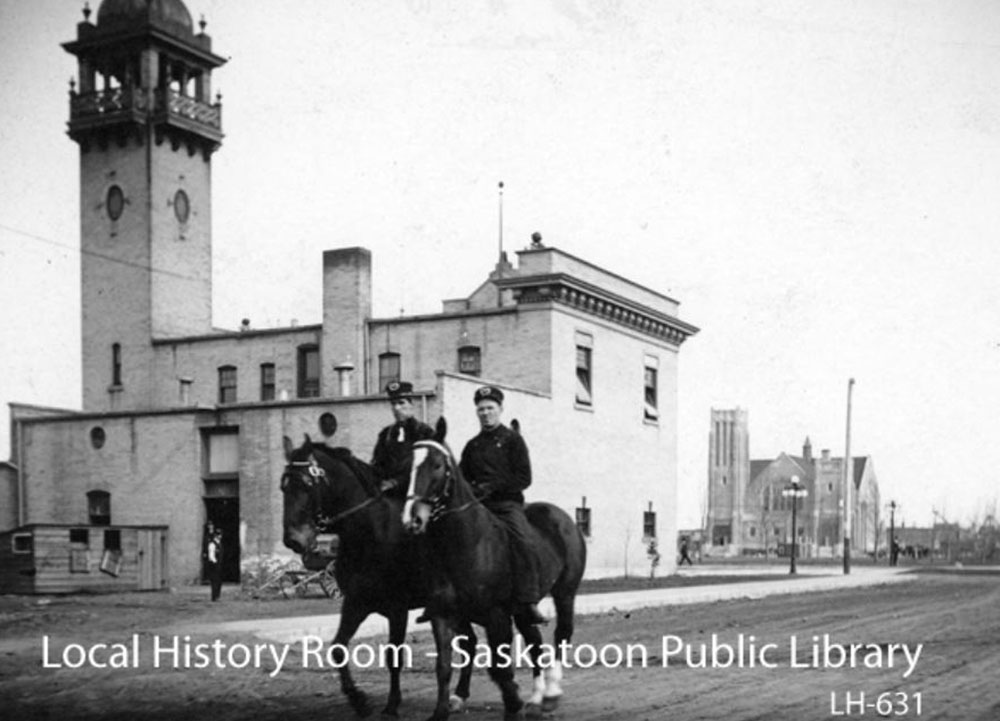

Fire Hall No. 1

Saskatoon Public Library LH-631

1910

Two firefighters on horseback pose in front of Fire Hall no. 1 in 1910. The firehall stood for almost 60 years before it was demolished in 1965.

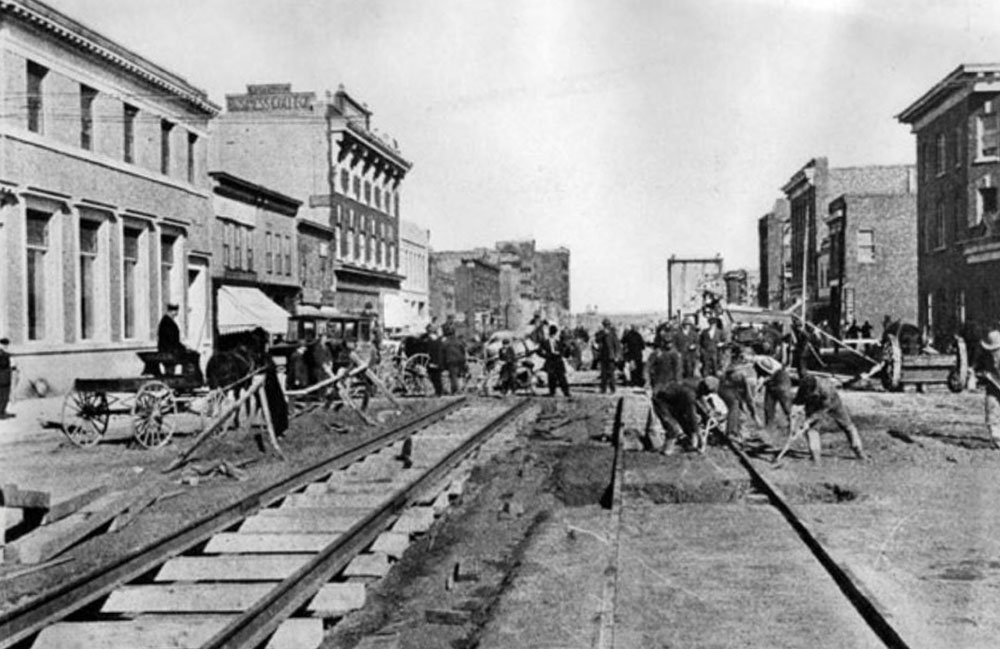

Paving Work

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2015-168

1912

A crew of workmen pave the intersection of 1st Avenue and 21st Street East in 1912 in the searing July heat.

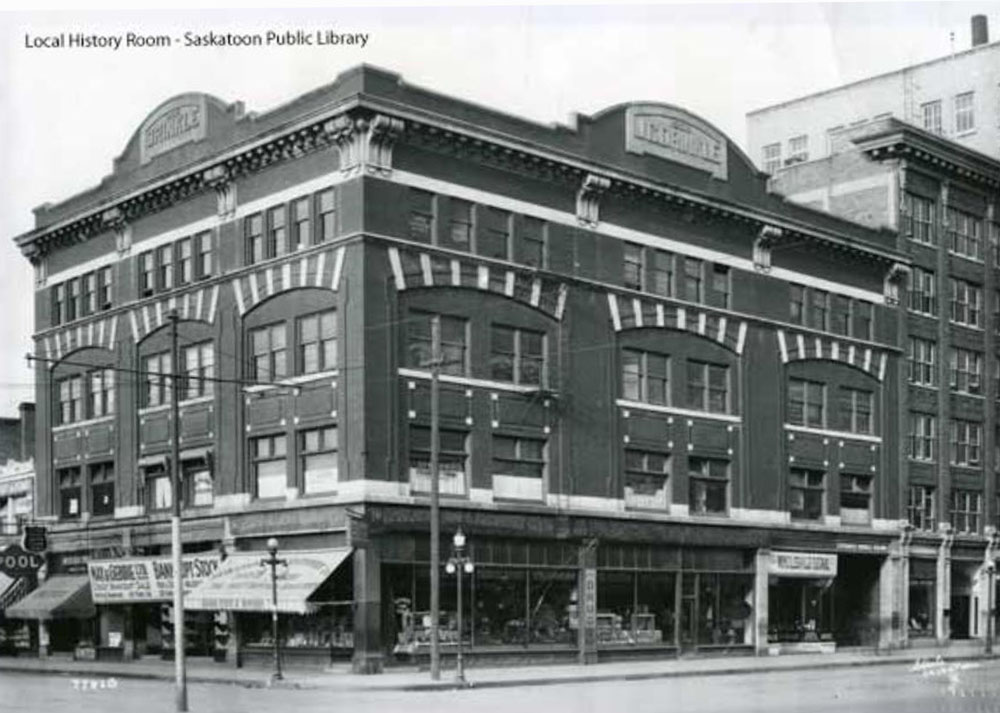

Secrets in the Concrete

Saskatoon Public Library LH-1583

1912

Like many other Canadian cities in the first decades of the 20th century, Saskatoon introduced streetcars as a method of public transportation in 1913. The streetcars officially opened for business on New Year's Day 1913 under the name of the Saskatoon Municipal Railway. 5,200 customers used the streetcars that first day, nearly half of the population at the time. Each rider paid the conductor five cents to experience the novelty. The streetcars served Saskatoon until 1951 when they were decommissioned, but that wasn't the last that Saskatonians would see of the old lines. In 2015, city crews conducted an emergency repair to a water line on the intersection of Broadway and 12th St. E. Upon digging up the old concrete, the surprised crew discovered a chunk of the old streetcar rail which had been sitting, hidden in the street for over 65 years.

Drinkle Building

Saskatoon Public Library LH-2025

1912

When John Clarence Drinkle built his self-titled Drinkle Building in 1909 it was the first large and modern business block in the city and boasted elevators and telephones, the latest innovations. It was destroyed by fire in 1925.

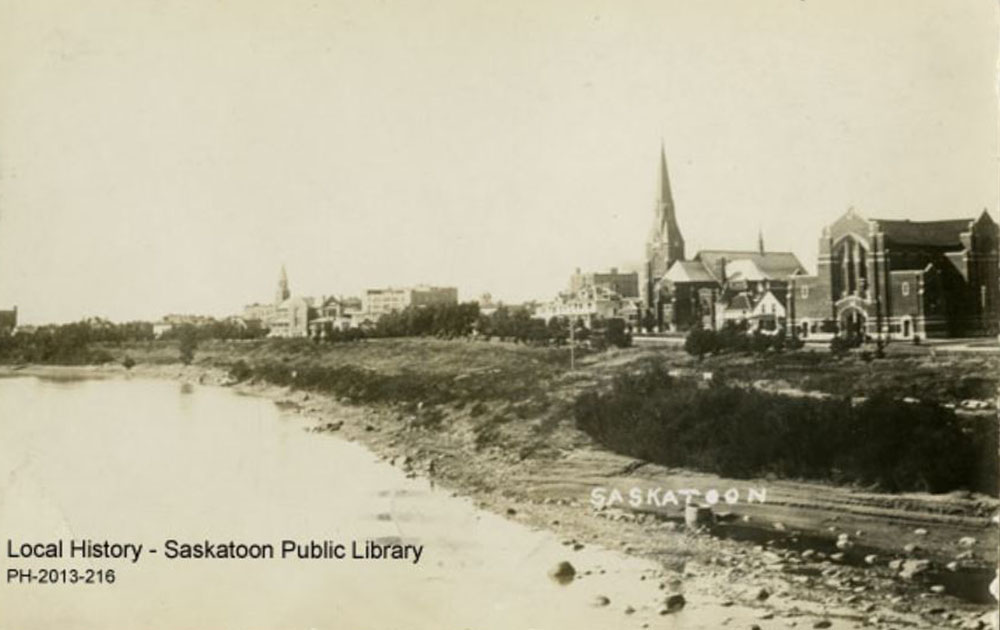

The Three Churches

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2013-216

1913

From University Bridge, you can spot three of Saskatoon's historic Churches. On the left, St. Paul's Roman Catholic Cathedral, St. John's Anglican Cathedral in the middle, and Knox Presbyterian Church on the right. These three churches represent only a fraction of the religious diversity that early Saskatoon had to offer. Saskatchewan as a whole was largely settled by groups of religious and ethnic minorities who formed bloc settlements on farmland. Between 1901 and 1921 the majority of Saskatonians were Protestant or Catholic, with a scattering of Methodists, Congregationalists, Lutherans, Doukhobors, Mennonites and Hutterites. But, as the city grew, the census began to reflect belief systems from around the world such as, Ukranian Catholics, Jewish, Orthodox, Budhists and several others.

Fighting a Fire

Saskatoon Public Library LH-5228-A

1922

Firemen fight to control a blaze on 2nd Avenue South in the 1920s as the structure collapses in a plume of smoke.

The University Bridge

Library and Archives Canada 3315922

1925

The University Bridge, named for its proximity to the University of Saskatchewan, was Saskatoon's first reinforced concrete arch bridge. While the new design was innovative, the bridge was plagued with controversy from the beginning. The original contractor, R.J. Lecky low-balled on the bid for the construction contract, and cut corners on expenses, leading to issues with sourcing quality concrete. He was subsequently slapped with a conflict of interest charge. One section of the bridge had to be rebuilt, but due to the outbreak of World War I and an economic depression the contracting company went under and the provincial government was forced to bear the burden of finishing construction themselves.

Aside from the legitimate scandals surrounding the bridge's construction, a few urban myths cling to the bridge as well. Some say that Lecky was so desperate to save money that he mixed straw into the concrete. Others claim a worker fell into the concrete molds during construction and perished, and that his remains are still in the bridge foundations. These legends, while entertaining, are only rumors and not supported by any historical evidence.

Fierce Winters

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2011-38

1927

Saskatoon is no stranger to winter storms. In this photo, an unknown man stands up to his shoulders in a massive snow drift that blocks the road. The caption on the photo captures some of the excitement of the event, "1st time we beat New York. Snow storm of March 14-15-1927." While the city received an impressive amount of snow in this storm, it was by no means Saskatoon's worst blizzard. The 10-day blizzard of January 1947, which blocked roads and rail lines from Calgary to Winnipeg, is named by Environment Canada the "Worst Storm in Canadian Railroad HIstory." The storm swept across the prairies, and in some communities, the only thing visible under all the snow were the very tops of telephone poles.

Choosing Sides

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2011-223

1934

By the 1930s, cars were really beginning to come into their own as a new innovative technology. Before this photo was taken, cars began to diversify and new companies were coming on to the market, some of which are recognizable today: Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Dodge, Fiat, Ford, Lincoln, and Oldsmobile. But, by the 30s, cars had developed even further, now boasting luxuries such as radios and heaters. The cars themselves advanced as well, with the development of automatic transmission and V-8, V-12 and V-16 engines. For Canadian drivers in the 1920s, each province fell into one of two parties, those who drove on the left, and those who drove on the right. Until the 20s, British Columbia and the Maritimes stuck to the staunchly British tradition of driving on the left hand side, despite most of central Canada, including Saskatchewan, choosing the left, like the majority of their American neighbors. Saskatchewan was on the winning side, and fortunately never had to adjust to the change.

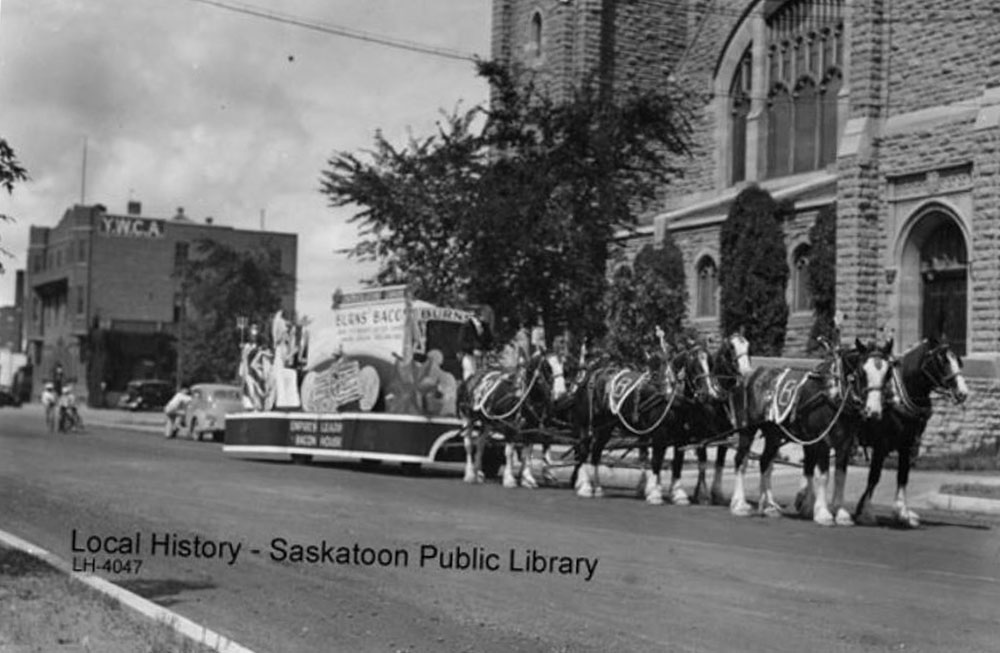

A Parade Float

Saskatoon Public Library LH-4047

1935

The burns float cruises down 24th Street East during the Saskatoon Exhibition Travellers Day Parade.

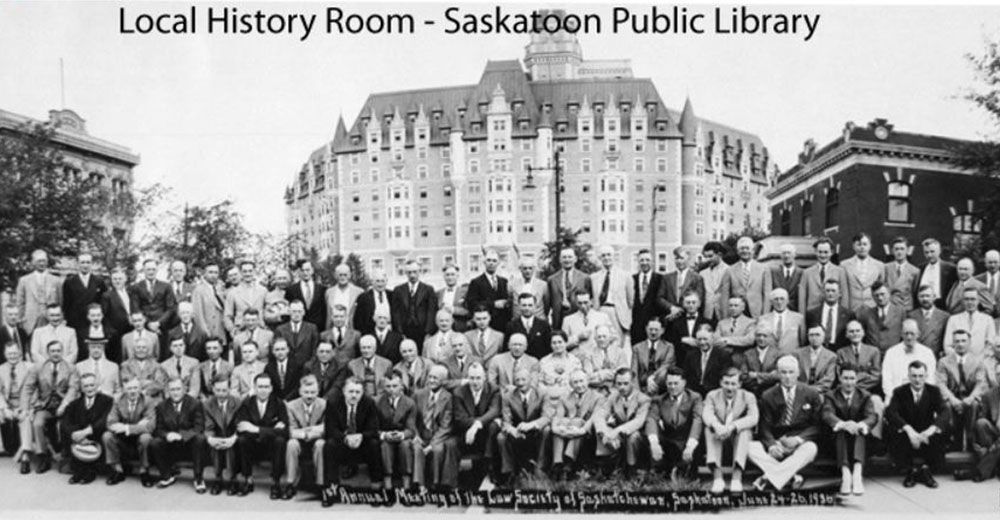

The Law Society of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon Public Library LH-3888

1936

Members of The Law Society of Saskatchewan assemble for a group photo at their first annual meeting June 24-26, 1936. The man in the centre is J. G. Diefenbaker. In this large group of men, one woman sits in the second row from the bottom, near the centre.

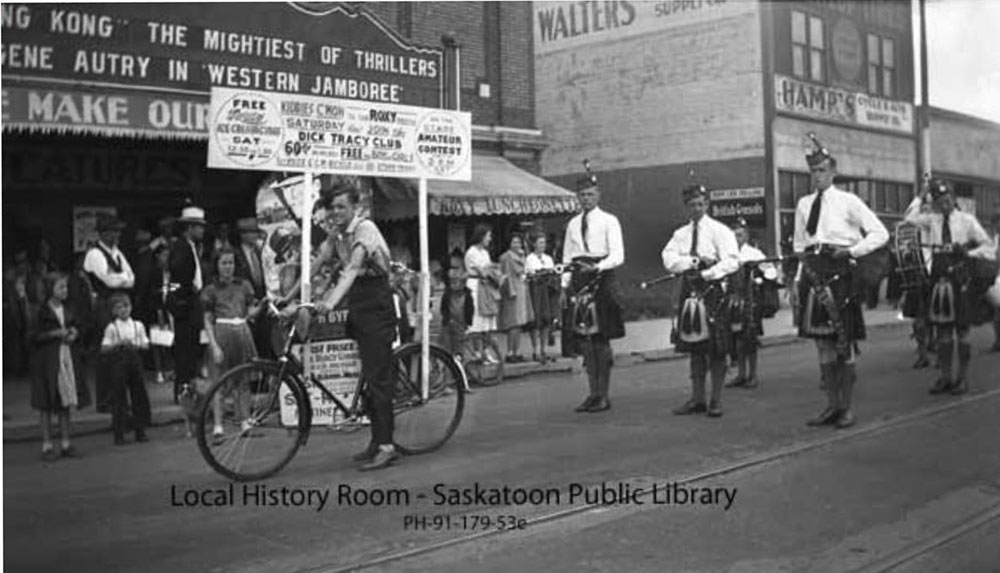

The Roxy Theatre

Saskatoon Public Library PH-91-179-53-E

1930s

This parade in front of the Roxy Theatre was orchestrated as a promotional spectacle to advertise the current films showing at the theatre; King Kong, and Western Jamboree.

Tommy Goon

Saskatoon Public Library PH-2014-384-1

1941

Tommy (Nee Foon) Goon stands in front of his barber shop in December 1941. Nee Foon Goon came to Canada in 1921 before the implementation the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which excluded almost all forms of Chiniese immigration.

"Your Country Needs You"

Library and Archives Canada 4315997

1940s

A couple fashionable women cross 21st Avenue East during World War II. On the left side of the street, a recruitment poster hangs on a lamppost encouraging young men to enlist. The design of the poster is one that is immediately familiar to many people, with most associating the classic pointing pose with America's Uncle Sam. However, the image originated with a British World War I campaign using the image of Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State during the Great War. Kitchener was a controversial figure, but is now remembered mostly for his foresight in predicting World War I's several year duration, and for his role in propaganda images.

Like the poster in this image, Kitchener's pointing likeness was accompanied by the slogan "Your country needs you." which played on nationalistic sentiments. David Bownes, from the National Army Museum in the United Kingdom, claims these words were so highly effective because "They evoke patriotism and guilt in those yet to enlist without straying as far as emotional blackmail." Kitchener's poster was so evocative that it was replicated and used worldwide for recruitment campaigns, including in Canada.