Walking Tour

City of Bridges

Life on the South Saskatchewan

Alexa Dagan

Saskatoon Public Library LH-3805

Every city needs a backbone - here in Saskatoon, it’s the slow moving waters of the great South Saskatchewan River. The river once provided water for the legions of buffalo who roamed the prairies, and the plains First Nations who hunted them, and now feeds the taps of every house in Saskatoon. As the backbone of the city, the river is a prominent character in almost every story from the city's history. Follow us on this tour as we follow the South Saskatchewan River through Saskatoon's major life events and growth into one of Canada's most prominent prairie cities.

This scenic riverbank tour starts at River Crossing on Spadina Crescent East, where you can see the devastating effects of the extreme prairie climate on the environment. After that, we’ll follow the promenade under the Senator Sid Buckwald Bridge, where we will find the next stop and learn about the geological foundations of Saskatchewan, along with the sad fate of the prairie buffalo. Then we’ll cross over the historic Traffic Bridge to learn about the settlement of Saskatoon by the Colonial Temperance Society. Mere steps away, we’ll see the “Worst Nautical Disaster In Prairie History,” that shook the foundation of the Traffic Bridge. We’ll leave the bridge for a nice walk along Meewasin Trail to Broadway Bridge, where we’ll learn how the site for Saskatoon was chosen and how the Great Depression spurred the bridge’s construction. After that stop, we’ll continue along the trail until we reach Saskatchewan Crescent East and 15th Street East, where we’ll learn about some of Saskatoon’s worst accidents, along with the affect wartime had on the city. Finally, we’ll end our tour at University Bridge for a reflection on the South Saskatchewan River’s continued importance to this day.

1. The Sea of Grass

Saskatoon Public Library LH-396

1905

In this 1905 photo, a collection of spectators take in the destructive results of the spring ice breakup. When Saskatoon's first bridge was built, it faced an impressive foe: the yearly breaking up of the ice which brought blocks of dense and incredibly sharp ice downriver, and the wooden foundations of the bridge (or pilings) were no match. Finally, in 1904, the settlement's only bridge washed away with the melting ice. Only a year later, the exasperated community gathered on the banks to watch the replacement bridge meet the same fate.

* * *

My father came west in the 'eighties To a land where the wheat grew like grass He got hit by the dust in the 'nineties Now he's going back East second class

It's forty below in the winter And it's twenty below in the fall It rises to zero in springtime And we don't get no summer at all1

The intensity of Saskatchewan's weather was matched only by the persistence of its insects. Rather than the traditional four seasons, pioneers insisted that there were actually five: Black fly season, mosquito season, horse fly season, house fly season and, winter.2 Despite these obstacles, settlers established themselves in the grain belt and by 1883, enough people lived here for Saskatoon to incorporate as a city.

2. The Bottom of the Sea

Library and Archives Canada 3393103

1910

In this photo, a ferry landed on the muddy banks of the South Saskatchewan River to load passengers for the river crossing. Two horse drawn carriages took up most of the room, but a handful of foot passengers were able to squeeze on by crossing a precarious ramp over the deep mud. Before Saskatoon became the city of bridges, settlers could only cross the river by ferry. The ferry was rather unreliable due to the fact that they only had a part time ferry driver, along with the yearly ice, shifting sand bars, and the river’s slow current.

Standing here, try to picture what it looked like 100 million years ago, this riverbed and the grassy prairie was the sandy bottom of a sea so vast that it practically split North America.

* * *

Around 11,000 years ago, while the glacier was receding, the ancestors of Saskatchewan’s Plains First Nations arrived.. While central Saskatchewan is the traditional land of the Cree and Nakota (Assiniboine) First Nations, other groups such as the Sioux and Saulteaux moved into the region, fleeing violence and persecution from white settlers. Now that the Ice Age was over with, the Cree and Assiniboine nations adapted to the newly available resources and quickly became masters of the buffalo hunt.

The arrival of the Europeans began the calamitous decline of both the buffalo and the Great Plains First Nations. For thousands of years, the buffalo provided them with food, clothing, shelter, and tools. In only a few short decades, the fur trade and mass hunting by Europeans pushed the buffalo to the brink of extinction. Even after the great herds were practically gone, the buffalo had one more gift to give. For a brief period in Saskatoon's early history, a line of buffalo bones lay stacked alongside the river in boxcar loads that stretched the length of approximately five city blocks. They were shipped from the prairies to be ground into fertilizer, and one other surprising commodity: a type of dishware made from a mix of ground bone and porcelain known as "bone china." The heavy, dense bones of the buffalo made for high-quality bone china, and even before Saskatchewan's agriculture burst into bloom, many consider the bones of the once plentiful buffalo to be the province's first major export.1

As high society British sipped tea from cups made of the bones of critically endangered buffalo, the indigenous populations of the plains were starving and facing total economic collapse as the buffalo herds, the primary basis of their subsistence and way of life, vanished.

3. Full Steam Ahead

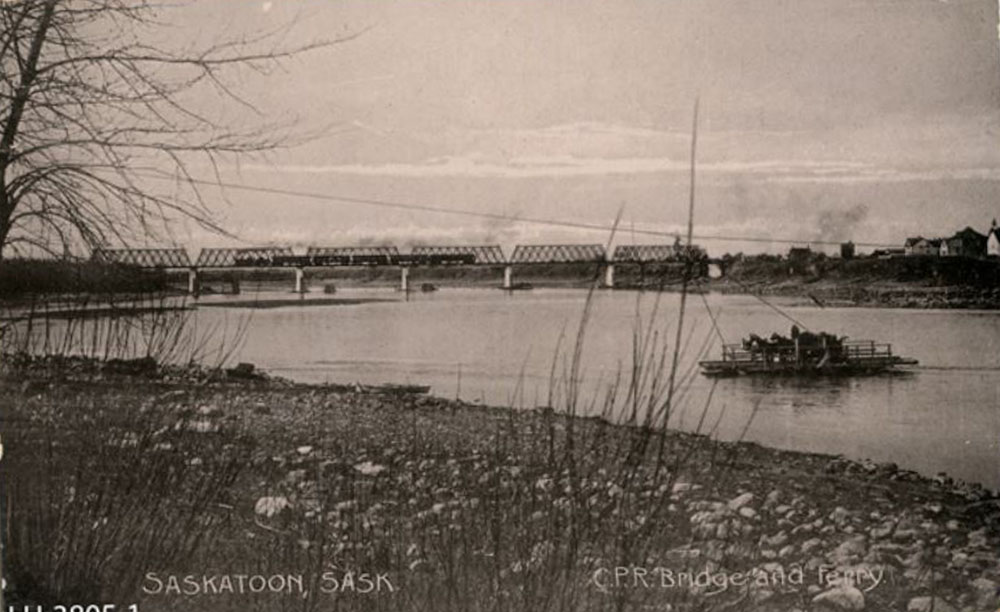

Saskatoon Public Library LH-3805

1905

This photo features the newly built Canadian Pacific Railway Bridge connecting the two halves of the recently incorporated city of Saskatoon. Spanning from eastern Alberta across Saskatchewan to Manitoba, the prairies are the nation's breadbasket, and Saskatoon is right in the middle. Throughout the 20th century and beyond, Saskatchewan's fertile soil and extensive river system supported vast fields of grain that were exported to a hungry world by these railways. The construction of railway lines and the trestles helped bridge not only the river, but also the geographical isolation of the prairies by anchoring Saskatoon as one of the primary railway hubs between eastern and western Canada.

* * *

Saskatoon was originally established by the Temperance Colonization Society, who believed that alcohol was responsible for many societal evils and wanted the community to be rid of it. They acquired land on the banks of the South Saskatchewan River in the hopes that the river would become the major shipping waterway of the plains. This hope was short-lived: the South Saskatchewan was too shallow, and had far too many shifting sand bars to compete with other major shipping arteries such as the Mississippi. While the river had been a good route for fur traders in canoes, it was incapable of supporting large scale 20th century shipping.

Despite the disappointment of the river, the settlers of the steadily growing community found another solution. If the river failed to connect them to the rest of the province, then they would forge that connection by rail.

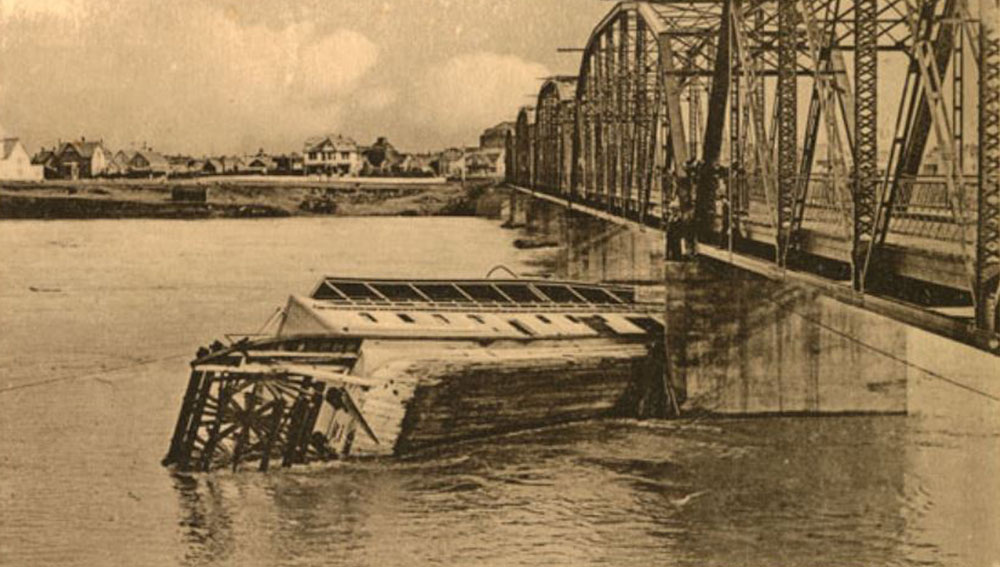

4. SS City of Medicine Hat

Library and Archives Canada 3364281

1908

In this photo, a ladder is lowered from Traffic Bridge to rescue the crew of the rapidly sinking luxury steamer, SS City of Medicine Hat. The spring of 1908 brought an unusually high volume of run-off, and the South Saskatchewan River surged with the elevated water. In what newspapers proclaimed the "Worst nautical disaster in prairie history," the steamship slammed into the columns of the Traffic Bridge. Fortunately, the passengers had disembarked before the accident, and the crew was able to safely escape by climbing up the bridge before the ship sank. In 2012, archaeologists uncovered over 1,000 artifacts from the riverbed that they are confident belong to the wreckage of the City of Medicine Hat.1

* * *

Initially, this future seemed almost out of reach. Out of Canada's three major railways, only the Canadian Pacific Rail planned to run through Saskatoon. Only after two years of lobbying by Saskatoon's new Board of Trade did the Grand Trunk Railway and the Canadian Northern finally agree to pass their lines through Saskatoon.

With all three railways secured, and new settlers flooding to the region daily, Saskatoon's meteoric ascent was undeniable.

5. "Last Best West"

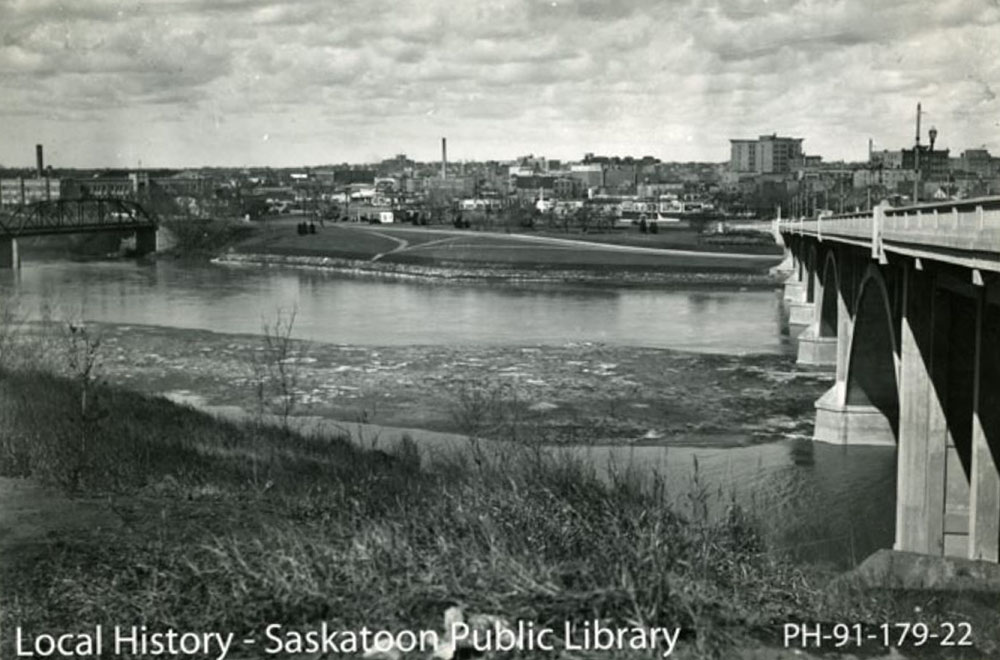

Saskatoon Public Library PH-91-179-22

1940s

By the time this photo was taken in the 1940s, the city's skyline had developed significantly since its boom period in the early 20th century. Forty years earlier, there were only 26 houses on the west side of the river. During the city's early heyday, the river served as a geographical boundary between the two sides of the city. The western side of the river had a few houses. As most of the land was devoted to industry and the railroads - the majority of the population had settled on the east bank.

* * *

The Temperance Colonization Society surveyed a number of sites along the river before finally deciding on the location of their new community. They began by surveying a 42 km long stretch of the river, and found the site on the east side of the Saskatchewan River perfect. The river was shallow here and was suitable for a ferry crossing. The grade on the east bank was also gentle enough for wagons.

The original settlement on the east bank originally chose the name Saskatoon, a name derived from the Cree name for the reddish berry that grows alongside the river. However, in 1901, the west side was officially incorporated as a town, and chose the name Saskatoon. Feeling as though their name had been stolen, the east side began going by the name Nuntana, until both settlements eventually amalgamated with the nearby settlement of Riversdale, and became the city of Saskatoon.1 Today, the neighborhood on the east side of the river, a couple blocks behind where you are standing, still goes by the name Nuntana.

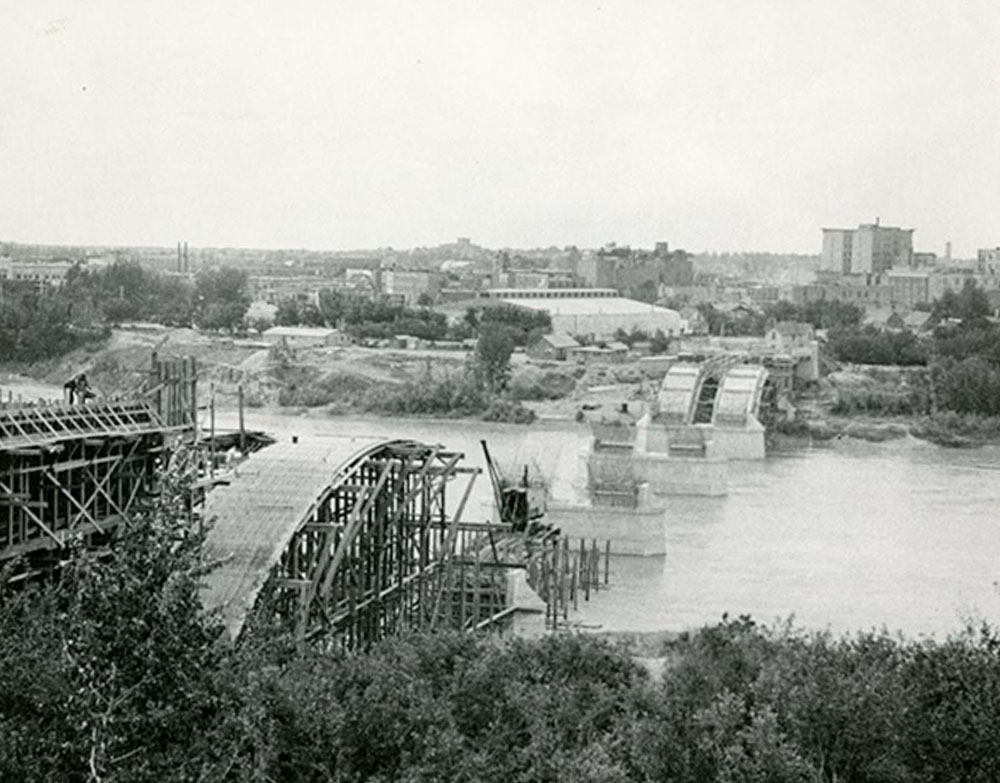

6. Black Storms

Saskatoon Public Library LH 3258

1932

In this captivating photo, the arches of Broadway Bridge are beginning to take shape against the backdrop of the west side of Saskatoon. While towns across Canada felt the strain of the Great Depression, Saskatoon, as an agricultural community, was hit particularly hard. The Broadway Bridge was a large scale unemployment relief project to help those who lost their jobs in the Depression. Starting in 1931, the bridge was built almost entirely by hand to maximize the amount of work required to employ the city's jobless masses. As you stand on this spot, take a moment to admire the bridge's structure, and imagine the amount of effort it must have required to build this bridge by hand.

* * *

For much of the 1930s, the net agricultural income of the province was negative; Saskatchewan was hemorrhaging money. By 1930, not even a year after the crash, the number of men in the unemployment relief camp in the exhibition grounds swelled to 500. That was only the beginning, and the number on the unemployment rolls continued to grow relentlessly. The Civic Relief Board, and the city's charities buckled under the flood of people needing assistance, and an attempt to move some working class political organizers to a camp in Regina ended with a riot in which one police officer was killed. The city limped along through much of the thirties, but by the time it regained its financial footing in the last years of the decade, the tension in Europe was boiling over into a conflict that threatened Saskatoon's tenuous regained stability.

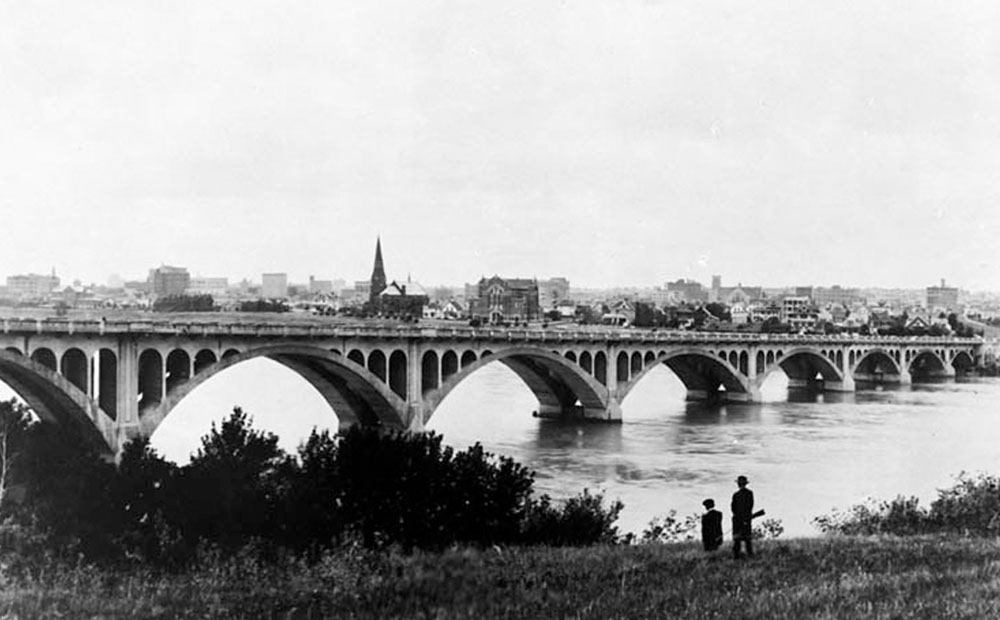

7. "The Hub City"

Library and Archives Canada 3315918

1923

In this 1923 photo, the city hugs the shores of the river and has spread to where the land meets the horizon. Although the city seems extensively developed in this photo, like most of Saskatchewan, the young city of Saskatoon was plagued by bad infrastructure. As a population who made their living from agriculture, most Saskitonians relied on automobiles for transport of people and goods. In the early 1920s, Saskatchewan had the most automobiles per capita in the country. However, despite this dependence on vehicles, throughout the entire province there was only a grand total of ten miles of gravel road, with most transport relying on dirt tracks, or rail.1

* * *

The worst accident, which happened at the height of the Second World War, caused a flurry of controversy. As the city readied itself for the possibility of an enemy attack, however remote it might be, city officials organized frequent fire, police, and first raid drills, and coordinated mock attacks on city governance and communications. If these measures kept citizens on their toes, overzealous military officials only aggravated tensions by urging Saskatonians to fear the presence of enemy agents hiding in their midst.

It was in this uneasy climate that caused speculation when a Canadian National freight train plowed into a Canadian Pacific Railway passenger car in 1943. The first thought on many people's minds was that it had to be an act of sabotage. Both trains had received green signals to progress through a railway crossing and collided violently. Most of the passengers escaped injury but, Colin Sands, the engineer of the CN train, was gravely scalded by the escaping steam from the engine and died of his injuries in hospital the next day. While both train lines called it a terrible accident, some remained convinced it was the work of enemy saboteurs.3

8. The Bessborough Hotel

Saskatoon Public Library A-2077

1940s

This photo shows the nighttime Saskatoon skyline illuminated by lights reflected in the slow-moving waters of the South Saskatchewan. The river begins as runoff from the Rocky Mountains, and passes through three provinces and several lakes before finally completing its epic journey by flowing into the ocean at Hudson's Bay. Despite this route to the ocean, Saskatoon remains a landlocked city. However, for the sailors who trained at Saskatoon's HMCS Unicorn, the distance from the ocean was a small obstacle, and the men trained there distinguished themselves in World War II in many engagements.1For a province battered and bruised by the depression, World War II came as a brilliant shock that resuscitated Saskatoon's industry. Just as the city recovered and the price of crops and cattle rose, the city mobilized for a war unlike any they had ever seen. During the First World War, students and faculty at the university enlisted and the school emptied. However, for World War II, the focus was on keeping the students enrolled and training both in their studies and in the military or war industries. Soon, the city took on the feel of a training camp. The college offered radio, ordnance, and technical training, the Royal Canadian Air Force opened a flight school, while the navy installed the HMCS Unicorn's naval barracks. While the name may seem ridiculous to some, it comes from one of the first ships to explore Hudson's Bay, and represents the remarkable record of brave sailors from an entirely landlocked province.

The HMCS Unicorn trained a total of 3,600 sailors in World War II, an impressive number for a small prairie city.2 According to Gail A. McConnell, while some mocked the sailors of the Unicorn as "bath tub sailors," the men overseas proved themselves distinguished and brave sailors.3 Today, the base remains in operation, and around a dozen recruits a year learn basic naval skills at the prairie barracks.

9. Beer and Bread

Library and Archives Canada 3315840

1920

When a photographer took this photo in the 1920s, the University Bridge was only a few years old. The bridge was meant to provide an easy link for those going back and forth between the west side of Saskatoon and the University of Saskatchewan on the east bank. The descending size of the bridge's arches were designed to mimic the arcs of a stone skipping across water.

* * *

Walking along the Meewasin Trail gives one an appreciation for how closely linked Saskatoon and the South Saskatchewan River are. The city's drinking water is drawn from the South Saskatchewan, and the power station at Gardiner Dam generates enough electricity to power 100,000 homes.1 The river also provides the water needed to irrigate wheat fields, and its massive watershed supports wildlife across Alberta and Saskatchewan.

The South Saskatchewan is in the backdrop of practically every scenic photo taken in Saskatoon, and the collection of bridges needed to cross its impressive width gives the city the title "Paris of the Prairies." Any loaf of bread made from central Saskatchewan wheat, or any beer produced in one of Saskatoon's much praised breweries, is grown or brewed with water from the South Saskatchewan. Because of this, people across Canada, without

Endnotes

1. The Sea of Grass

1. Gail A. McConnell, Saskatoon: Hub City of the West, (Saskatoon: Windsor Publications (Canada) Ltd., 1983), 16.

2. McConnell, 15-16.

2. The Bottom of the Sea

1. William P. Delainey, John D. Duerkop, William A. S. Sarjeant, Saskatoon: A Century in Pictures, (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1982), 13.

3. Full Steam Ahead

1. Delainey, Duerkop, and Sarjeant, 45.

4. SS City of Medicine Hat

1. The Globe and Mail, "Shipwreck from 1908 found in South Saskatchewan River," Nov. 15, 2012, online.

2. McConnell, 37.

5. "Last Best West"

1. McConnell, 28.

6. Black Storms

1. McConnell, 48.

7. "The Hub City"

1. McConnell, 25.

2. CTV News Saskatoon, "From streetcars to hybrids: the history of Saskatoon transit," July 24, 2013. Online.

3. Bill Waiser, "Trains collided on Saskatoon's west side during second world war," Bill Waiser. Website. January 3, 2018.

8. The Bessborough Hotel

1. McConnell, 54.

2. Jacqueline Wilson, "Inside HMCS Unicorn, Saskatoon's navy recruiting base," Global News, April 23, 2016. Online.

3. McConnell, 54.

9. Beer and Bread

1. Meaghan Craig, "Saskatchewan's Gardiner Dam turns 50 and it's still pretty spectacular," Global News, July 14, 2017, online.

Bibliography

Anderson, Alan B. Settling Saskatchewan, Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013.

Craig, Meaghan, "Saskatchewan's Gardiner Dam turns 50 and it's still pretty spectacular," Global News, July 14, 2017. https://globalnews.ca/news/3600416/saskatchewan-gardiner-dam-50/

Delainey, William P., John D. Duerkop, and William A. S. Sarjeant, Saskatoon: A Century in Pictures, Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1982.

McConnell, Gail A. Saskatoon: Hub City of the West, Saskatoon: Windsor Publications (Canada) Ltd., 1983.

Waiser, Bill. "Trains collided on Saskatoon's west side during second world war," Bill Waiser. Website. January 3, 2018. https://billwaiser.com/trains-collided-saskatoon-second-world-war/

Wilson, Jacqueline. "Inside HMCS Unicorn, Saskatoon's navy recruiting base," Global News, April 23, 2016. Online. https://globalnews.ca/news/2657609/inside-the-hmcs-unicorn-saskatoons-navy-recruiting-base/

"From streetcars to hybrids: the history of Saskatoon transit," CTV News Saskatoon, July 24, 2013. Online.

"Shipwreck from 1908 found in South Saskatchewan River," The Globe and Mail, Nov. 15, 2012. Online