Walking Tour

For or Against Canada?

Niagara Falls, Enemy Aliens, and Canada's Defense

During the First World War, the Niagara Armoury served as a receiving station for interned enemy aliens. It was also a focal point for Canada's defense from suspected German sabotage plots originating in the United States.

In this tour we will learn about the fascinating military history of Niagara Falls, and its role in Canada's defense from the War of 1812 to the First World War. We will learn about the anxieties and fears—some outlandish—that gripped Canada during the Great War, and how the Canadian government responded by internin g dozens of men here. Finally we will learn about the so-called 'enemy aliens', who fought bravely for Canada, a country that demonized and persecuted them solely on the basis of their national origins.

Tour Route

This is a brief walking tour around the exterior of the armoury, which is today home to the Niagara Military Museum, a fantastic museum we strongly encourage you to visit after this tour.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. The Niagara Frontier

ca. 1915

Here we see Niagara Falls' Armoury around the winter of 1915.

The Niagara River has been fundamental to the defense of British North America (and later Canada) ever since the Canadian-American border was drawn here. During the 19th century it was the scene of diplomatic jockeying, farcical invasions, and epic battles.

The pivotal War of 1812 battles at Queenston Heights (1812) and Lundy's Lane (1814) were fought within a short distance of this spot. Canada's survival as a British colony—and therefore its current existence independent from the United States—was due in no small part to the outcome of these battles.

* * *

Two centuries ago the situation was rather different. The United States had only just gained independence from the globe-bestriding British Empire, and the British were intent on keeping control of their remaining North American colonies. Thousands of refugees—the United Empire Loyalists—had resettled in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) so they could remain British.

When the War of 1812 broke out, the Americans were wildly overconfident that they could expel the British from the continent entirely. Former president Thomas Jefferson said the conquest of Canada would "be a mere matter of marching."1

The Americans intended to overwhelm the much smaller defending force of British regulars, Canadian militia, and Indigenous allies by launching multiple invasions along different axes. In 1812 these efforts failed in the face of the bold and determined leadership of General Sir Isaac Brock, though he was killed at the head of his men at the Battle of Queenston Heights.

The Americans invaded across the Niagara frontier again in 1813—and again in 1814. These campaigns very nearly succeeded in routing the British from Upper Canada completely. It was only thanks to the doggedness of the Anglo-Canadian-Indigenous defenders, incompetence of the American commanders, and no small amount of luck, that the Americans were finally driven back across the Niagara River. When the war ended the river remained the border. Canada had been saved.

It would be 50 years before this boundary would once again become a battlefield.

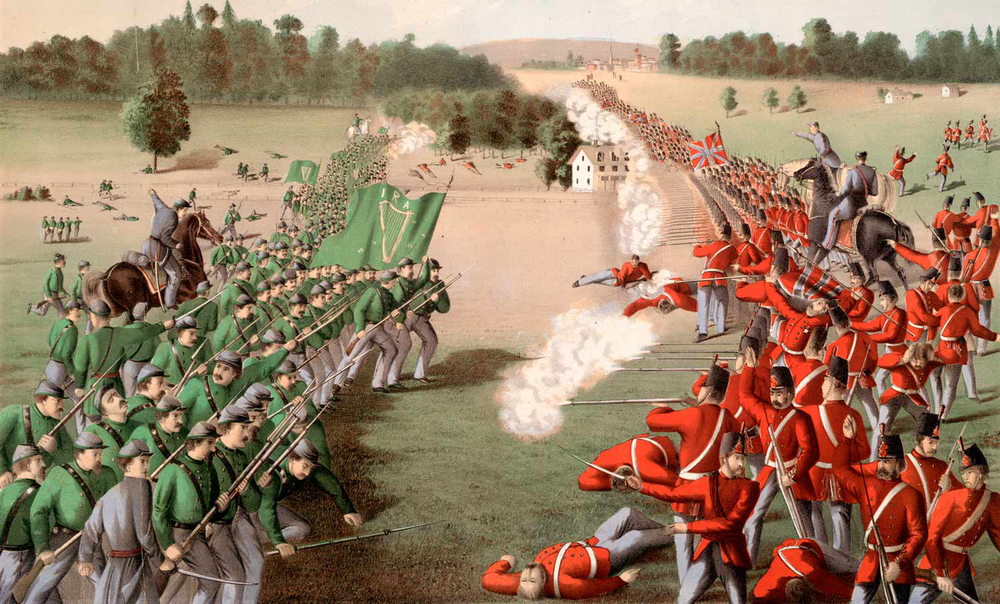

2. The Fenian Raids

1911

A horse drawn buggy in front of the armoury, with four individuals standing in the doorway. This photo was taken in 1911, the same year the armoury was completed.

During the First World War the Fenian Raids weighed heavily on the minds of Canadian politicians. These were abortive invasions of Canada by Irish-American Civil War veterans in 1866 and 1870-1. They intended to conquer Canada and use it as a bargaining chip to secure Irish independence from Britain.

It was an outlandish scheme which should have had little hope of success, yet the Canadian defense came off remarkably badly. The Battle of Ridgeway, the first battle ever fought by Canadian troops under Canadian command, was a disastrous defeat. It showed that Canada would have to take its own defense much more seriously. This was especially true as Britain was scaling back its commitments to Canadian defense, and the post-Civil War American republic was resuming its relentless expansion across the continent. The raids were a key contributing factor to Canadian Confederation in 1867.

In 1914, all these events were a lifetime away, yet they still caused worry. Canada's population was 7 million, yet America had almost 9 million German-descended immigrants alone.1 Most of them were concentrated in the midwestern states around the Great Lakes. Many were in Buffalo, just across the Niagara River. Could there be a repeat of the Fenian Raids, but on a vastly larger scale?

* * *

In 1866 America had just finished fighting a brutal and shockingly bloody civil war. Over 600,000 had died, some 2% of the population. With 1,700 casualties, the Battle of Lundy's Lane was the bloodiest battle of the War of 1812. At the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 there were over 51,000 casualties.

With Union victory in 1865, America was once again ready to look outwards. They had already expanded their borders all the way to the Pacific Coast, and stripped Mexico of over half its territory after a short, sharp war. Many American politicians loudly proclaimed it was their nation's "Manifest Destiny" to dominate the entire continent. Some made no secret that they intended to annex Canada too.

The Canadians could be forgiven for being nervous. Canada had undergone the same trends of immigration and industrialization, but only in microcosm. By 1866 in terms of population, industrial production, and military might, Canada was a mouse next to the American elephant.

The end of the US Civil War also meant hundreds of thousands of veterans were now unemployed. Many were Irish immigrants who had fled man-made famines and violent oppression in their British-ruled homeland. The Fenian Brotherhood was an organization of Irish Americans that sought to achieve Irish independence , and they recruited heavily from these demobilized soldiers.

To the Brotherhood's leaders, Canada presented a tempting target. If they could take and hold even a part of it, they might spark a political crisis in London, bringing about a reevaluation of demands for Irish independence.

On June 1, 1866, over 1,000 Fenians crossed the Niagara River near Fort Erie, intending to attack the Welland Canal. This was done without the American government's blessing, and later that day an American warship began blocking further Fenian reinforcements and supplies from crossing over from the American side.

In response, some 850 hurriedly-assembled Canadian militia marched overnight to confront the invaders. They met the Fenians at the Battle o f Ridgeway. The militiamen were "mostly teenage boys and young men, some as young as fifteen years old," and included two companies of University of Toronto students. They had little more than weekend training and fewer than half had ever fired a gun before. They were desperately short on ammunition, food, water, and didn't even have good maps. The Fenians were veterans of bloody civil war battlefields—likely amongst the best soldiers in the world at the time—and they had no shortage of supplies.2

When the militia encountered Fenian skirmishers their commander Lt. Col. Alfred Booker ignored his orders not to engage, and instead ordered an attack. Unfortunately they were walking into a trap, and the skirmishers were luring the Canadians towards the main Fenian force. Yet before they could even meet that force, disaster struck.

It's not clear exactly what happened. In the most common version of events, the Canadians mistook some mounted Fenian scouts for a body of cavalry, and Booker gave the order to form squares to fend off cavalry attack. Forming squares was a complicated order to carry out on a parade ground, let alone under intense and accurate Fenian rifle fire, and it caused chaos to break out amongst the poorly-drilled militiamen. Booker quickly realized his mistake and countermanded the order, but by then his force was turning into a rabble. The commander of the Fenian advance units saw an opportunity and ordered a bayonet charge. The panicked Canadians broke and fled from the field, leaving their dead and wounded behind.3 They lost 9 dead, and several more later succumbed to their wounds.

The Fenians won another small victory later that day at Fort Erie, but cut off from their expected reinforcements, and believing that much larger Anglo-Canadian forces were gathering, they retreated back across the border.

The raid was a stinging humiliation for Canada. Even though the government had known for months such a raid was likely, its preparations had proven completely inadequate. The militia had disintegrated before it even encountered the main Fenian force. If the US Navy hadn't halted Fenian reinforcements, it may have proven embarrassingly difficult to eject the raiders from Canadian territory.

Numerous investigations sought to pin the blame on the militiamen themselves, while protecting the reputations of Booker, the other officers, and the minister of militia, who had put such poorly-trained and equipped men in an unwinnable position.

The minister of militia, managed to emerge from the debacle with his reputation intact thanks to "two military board of inquiries staged to explicitly cover up the extent of the disaster."4 The minister's name was John A. Macdonald, and he became Canada's first prime minister a year later.

The historian Peter Wronski called the Fenian Raids "a kind of 'big bang' to Canada's gathering universe of nationhood." It is difficult to understand Canadian Confederation in 1867 without putting it in context of the raids.5 However, because these events were so embarrassing for everyone involved, they were largely wiped from the national memory and their history "distorted and falsified," so as to protect the reputations of men like Macdonald.6

3. The Militia's Armoury

ca. 1920s

A quarter view of the Niagara Armoury. It was one of a series of armouries built across the country in the years before the First World War as part of a scheme to modernize and expand the militia. Like most Canadian armouries from this period, it was built in the Gothic-Revival style to mimic the appearance of a castle of the late middle ages; it includes exaggerated 'turrets' at the corners, a crenellated parapet, and tall, narrow Gothic-style windows.

The armoury was a base, depot, and training centre for the Lincoln Regiment, a militia unit based here and at St. Catharines. The Regiment was activated to fight against the Fenian Raids in 1866 and 1870, and then reactivated at the outbreak of the First World War. During the war the regiment wasn't sent overseas, but instead contributed troops to several infantry battalions, including the 4th (Central Ontario), 81st, and 176th (Niagara Rangers). The latter two were sent to Europe and broken up to provide replacements for the devastated Canadian units already in the field.

The armoury also served as a receiving station for interned enemy aliens.

* * *

Today, relatively little is known about the actual conditions of the internment and detention facilities inside the armoury during the war. However it is thought that the rifle range in the basement was converted into cells for the internees.

A peak of 42 internees were held here before being transferred, along with 21 others in regular detention. Cramming over 60 men in the dark, dank, and smelly basement would have been a profoundly uncomfortable experience.1

We know of one escape from this station: In 1917 one George Heinovitch, an Austrian who had been arrested in Windsor, found the armoury's back door had been left unlocked. He took his chance and disappeared into the night. All of the guards and officers on duty at the time were severely disciplined for their lax adherence to security protocols—an ongoing problem at all the Canadian internment camps.

Most of the internees confined here did not stay long, but were sent onwards to camps at Fort Henry or Kapuskasing. On one occasion, when a number of those arrested in Fort Erie were being held here, wild rumours began to spread that their friends in Buffalo were planning a daring cross-border raid to seize the armoury and free the prisoners. These fears were taken seriously enough that the internees were hurriedly transferred to the more secure and distant internment camp at Fort Henry in Kingston.2

4. Reservists, Spies, & the Destitute

1911

A quarter view of the armoury, which between 1914 and 1918 was used as a receiving station for interned 'enemy aliens'. Who were the men that were imprisoned here, and what had they done to warrant such treatment? As we will see, the criteria for interning these men was arbitrary, unfair, and cruel.

* * *

It also reclassified several hundred thousand immigrants from enemy countries as 'enemy aliens,' depriving them of most of their civil rights, preventing them from leaving the country, requiring they register with the authorities and report regularly. It also threatened them with internment in a nation-wide network of camps. Which 'enemy aliens' were liable to be sent to one of these camps was left to the whim of local authorities across Canada.

Many of these 'enemy aliens' were men who had trained as reservists in the German or Austro-Hungarian armed forces, and were being called back home to fight. Those in this group who were apprehended at the border were arrested and processed at receiving stations like this one. In one instance in October 1914, 17 Austro-Hungarians were arrested trying to cross into America. It was claimed they were trying to join the Austrian army, but it's more likely they had probably been fired from their jobs and were going to America to find work rather than starve in Canada. This was certainly the case for the vast majority of enemy aliens arrested trying to get to America. Nevertheless, the Niagara Falls Evening Review described the prevention of their "escape" as a "coup" by the Immigration Authorities, and further noted that a "Toronto Ticket Agent" who allegedly assisted them could be charged with treason and face the death penalty.1 In addition to those caught trying to cross the border, those accused of spying or sabotage could be interned. Enemy aliens could be sent to an internment camp for nothing more than a careless remark, or an unlucky encounter with a police officer. Most of those brought to the Niagara Armoury receiving station fell into these categories.

Take this incident described in a press account from December 1914. At the Dominion Chain Company's Christmas party, an "official of the company" named Frank Pfeiffer, was "called upon for a speech and replied with a German ditty. The song failed to make a hit and the banqueters dispersed after a heated war argument." Pfeiffer and the company's general manager, another German named V.O. Ryckman, were arrested and interned at the Niagara armoury.2

The Canadian government also made unemployment and destitution among 'enemy aliens' an internable offense. Of the 8,579 people interned during the war, it turned out that the majority were poor Austro-Hungarian men—mostly ethnic Ukrainians. At the Niagara Falls receiving station however, these seem to have accounted for only a small proportion of the internees.

5. Invasion Rumours

ca. 1910s

This was the location of the Hydro Electric System building, located at the corner of Victoria and Armoury avenues, just across the street from the armoury. Throughout the early years of the war there was widespread fear in Canada that the large numbers of German and Irish immigrants living across the border could mount sabotage attacks on the critical infrastructure around the Niagara frontier.

Especially worrying was the critical Welland Canal, which connected the four western Great Lakes with Lake Ontario, and from there the St. Lawrence seaway and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. It was, as one August 1914 newspaper report put it, "the main artery for wheat from the Canadian northwest to England."1

* * *

Reports that there were 8,000 more Germans in Buffalo than usual, sparked fears they were gathering for a Fenian-style raid.

Reports of sensational German designs on the Niagara Frontier continued for years. In February 1916, the Toronto Daily News ran an article with a headline blaring "PLOT IS UNEARTHED TO INVADE CANADA?"

The article reprinted claims in the New York Herald that described how "the Canadian Secret Service had uncovered a plot of enormous proportions." It included: 200,000 Mauser rifles stored at secret depots on the Niagara border to arm a German-American invasion force. There were apparently "scores of German army officers recently arrived in the United States in the guise of Belgian refugees… with the object of heading an armed force for the invasion of Canada." It also claimed that a third of American weapons output had been "purchased by German agents masquerading as agents for the Allied governments."3

This was all of course a fantasy. Sometimes the press tried to tamp down these rumours, such as in this article by the Toronto Daily News:

"The chances of an armed invasion of Canada along the Niagara frontier, by any considerable body of Germans or German sympathizers across the river in Buffalo are so slight as to be practically none at all… A careful investigation by The News… has proved the fear of such an occurrence to be absolutely groundless.

A local official in Fort Erie told the paper: "The whole scare is the result of mischievous newspaper talk which cannot but have a bad effect and stir up ill-feeling where nothing but the best good-will exists."4

Nevertheless, invasion rumours continued to be taken seriously until America joined the Allies in April 1917. Throughout that time these reports fueled public paranoia and contributed to the denouncement and internment of many 'enemy aliens.'

6. German Plots

1914

This 1914 view down Armoury Road shows the armoury and, at right, the Carnegie Library, which was one of hundreds donated to cities across the English-speaking world by the Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

It is easy to dismiss out-of-hand fears of a German-American invasion, and conclude that Canadians were simply in the grip of wartime hysteria. Yet the German government did seriously entertain such schemes, including a failed plot to blow up the Welland Canal.

Some of their plans, in which they invested considerable time and energy, make the most preposterous reports in the Canadian press look like sober-headed analysis.

* * *

This scheme was pretty much the only active German attempt to launch a sabotage attack on Canada during the war. Captain von Papen was expelled by the United States for his poorly-laid scheme. Interestingly, von Papen would go on to become the last chancellor of the Weimar Republic in the 1930s. Much to the misfortune of all mankind, he handed power to Adolf Hitler, who he foolishly believed he could control.

Back in Germany, officials delighted in imagining schemes to strike Canada that went well beyond merely dynamiting the Welland Canal. Arthur Zimmermann, at the time an under-secretary at the German Foreign Office, envisioned an invasion of Canada with an army of 650,000 Irish- and German-Americans. This army would achieve the element of surprise by approaching the border wearing cowboy costumes instead of military uniforms, though it was debatable if cowboy costumes would be admissible as military uniforms under international law. "Much legal expertise was devoted to this tricky point," writes the historian Martin Kitchen.2

Apparently more thought was given to the cowboy costume question than the head-scratching logistics of arming, training, and organizing a secret army of some 40 divisions within the United States—a force four times larger than America's own military.

What the American government might have to say about this was also an afterthought. Given that Zimmermann is best known to history as author of the infamous Zimmermann Telegram, perhaps his questionable grasp on reality is not all that surprising.

The telegram was a secret proposal Zimmermann made to Mexico in 1917, asking them to invade America. In return Germany would give them financial aid and give Mexico the states of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. It was not clear how Germany could send Mexico this money, nor was it clear how Germany could ever take these states from America and give them to Mexico. Furthermore, Mexico was in the midst of a civil war, and its military was tiny, poorly organized, and equipped with many of the same antique weapons that it had fought and lost the Mexican-American War with some 70 years before.

The telegram was intercepted by British intelligence who published it. The Germans might have gotten away with calling it a fake, given how ludicrous the proposal was, but bafflingly, Zimmermann publicly admitted that the proposal was genuine. In response an outraged America declared war on Germany. This was a decisive factor in Germany losing the First World War, making the Zimmermann Telegram arguably the most fateful and idiotic diplomatic blunder in history.

7. Friend or Foe?

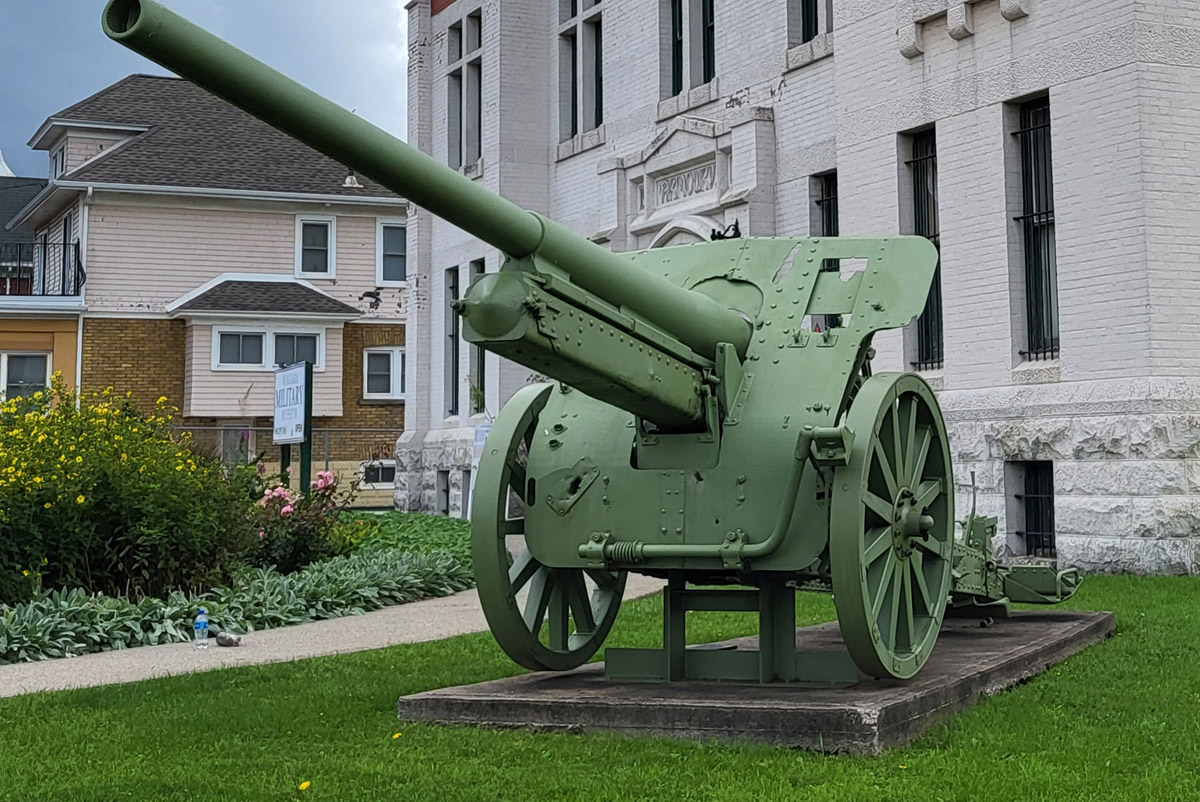

1982

A German field gun captured during the First World War by the Canadian Expeditionary Force is mounted in front of the Niagara Armoury. Hundreds of war trophies like this were distributed to communities across Canada after the war, reminders of the formidable fighting prowess and great victories of the Canadian Corps.

'Enemy aliens' were barred from serving in the Canadian military, but many were still able to enlist by adopting assumed identities. Some, however, were identified and denounced as spies. They were arrested, stripped of their uniforms, and sent to internment camps.

Determining who was an 'enemy alien' and who an allied citizen was not as simple as one might think, and made doubly difficult by the complex political geography of Europe. Eastern Europe and the Balkans had been carved up by the great powers with little regard for ethno-linguistic boundaries. Therefore ethnic Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, Serbs, and Italians, among others, could have immigrated from both enemy countries (Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Turkey) or allied countries (Russia, Italy, Serbia, Romania).

* * *

Take the example of Nikola Yerich. He was a Serb immigrant who was arrested at Welland in 1914, passed through the Niagara Receiving Station, and then sent to the internment camp at Kapuskasing. Serbia was an Allied power—indeed the invasion of Serbia started the whole war—but some Serbs still lived in Austrian territory. Yerich had come from those Austrian borderlands, so despite his hatred for that oppressive regime, he was nevertheless interned as an enemy alien. Yet his own nephew, Milan, died fighting in the Serbian army in 1918.1

The press carried frequent reports of men with Slavic-sounding names being denounced and arrested. A July 1915 article in the Niagara Falls Evening Review wrote: "Matthew Kaliejuk, who enlisted here a few days ago, giving his nationality as Russian, is an Austrian, and it is charged he is an enemy spy. He has been made a prisoner of war and stripped of his uniform."2

That November one J. Maychrzak was arrested in Fort Erie since it was claimed he was a "German Pole."3 Four men "who stated they were Roumanians," were arrested at the border because their papers "proved they were Austrians."

On another occasion, the body of John Ryarczuk was found in the railyard at Niagara Falls, after apparently being crushed while trying to hop a train and cross the border. He was described as an "Austrian reservist" carrying both Austrian and Russian passports, though the Russian passport apparently belonged to someone else.4

The Niagara Falls Evening Review opined: "The immigration authorities have their hands pretty full just now in preventing aliens from making their way East to join the enemy's forces."5 It was always assumed these men were trying to join an enemy army. But in the overwhelming majority of cases, they were leaving Canada out of desperation. Finding a job as an 'enemy alien' was close to impossible in the early years of the war. For many, their choices were go to America to work, starve on a Canadian street, or languish in a Canadian internment camp.

Some of these men may very well have been allied citizens who were wrongly accused of being enemy aliens by authorities that didn't bother to carefully investigate the complicated geography of eastern Europe. There were many embarrassing cases where Italian, Russian, American, Danish, and Romanian nationals were mistakenly interned as enemy aliens. Outraged consular officials from these countries had to intervene to secure their release while chastising the clumsiness and ignorance of Canadian officials.6

On another level, what these examples illustrate is the absurdity of a system of classifying and condemning immigrants to Canada based solely on the status of Europe's borders in August 1914. The entire concept is so arbitrary it makes a mockery of the fundamental principles of Canadian justice.

8. Fighting for Canada

ca. 1916

A wartime photo of some of the soldiers in the garrison, along with two men and a woman who appear to be civilian staff. The soldiers seen here were likely the ones tasked with guarding the internees held in the armoury's basement.

There were certainly some 'enemy aliens' in the Canadian Army who evaded detection and fought for Canada. For obvious reasons, historians have struggled to make even an approximate guess at their numbers.

One estimate based on analysis of last names puts the number of ethnic Ukrainians in the Canadian armed forces at 3,000 to 4,000, out of an estimated 6,000 with Slavic origins—though what proportion were allied citizens or enemy aliens remains unclear.

Many of these men distinguished themselves on the battlefield. One Ukrainian-Canadian, Filip Konowal, received the Victoria Cross, the British Empire's highest award for valour. He is one of only 94 Canadians to have ever received it.

* * *

Few eyewitness accounts exist of what the experience of war was like for these men, of whom a number spoke only little English, and many more were illiterate. One rare account from a Ukrainian Canadian veteran recalled the comradeship amongst his countrymen in the trenches:

"Our boys always tried to gather together in foxholes or trenches and there hummed the Ukrainian language and song. They were usually joined by intruding Muscovites and Poles, for the latter felt themselves more 'at home' among our boys, than among the English or French… Usually friendly conversations went on about village life in various parts of Ukrainian lands - about the land, harvest, customs, and such vital events as important holidays, religious feast days, weddings, and evening parties."3

The best known Ukrainian to fight for Canada was Filip Konowal. He was one of those who identified as Russian officially, but came from Ukrainian lands and considered himself Ukrainian. He worked as a lumberjack in British Columbia and Ontario before enlisting in 1915 with the 77th Ottawa Battalion.

He fought at the Somme in 1916, and with distinction at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where he led a squad of Japanese Canadian soldiers in the capture of an important defensive position known as "The Pimple."

It was at the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917 that he earned his Victoria Cross. Gaining distinction in the titanic and horrifying battles of the First World War required truly staggering personal bravery and determination. His medal citation makes it evident that Konowal was a one man army:

"For most conspicuous bravery and leadership when in charge of a section in attack. His section had the difficult task of mopping up cellars, craters and machine-gun emplacements. Under his able direction all resistance was overcome successfully, and heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy. In one cellar he himself bayonetted three enemy and attacked single-handed seven others in a crater, killing them all.

"On reaching the objective, a machine-gun was holding up the right flank, causing many casualties. Cpl. Konowal rushed forward and entered the emplacement, killed the crew, and brought the gun back to our lines.

"The next day he again attacked single-handed another machine-gun emplacement, killed three of the crew, and destroyed the gun and emplacement with explosives.

"This non-commissioned officer alone killed at least sixteen of the enemy, and during the two days' actual fighting carried on continuously his good work until severely wounded."4

9. The End of Internment

1934

A post-war photo showing the cast of a performance dressed in period costume. They are marking the rededication of Old Fort Niagara in a ceremony in front of the armoury.

The receiving station in the armoury's basement was shut down in August 1918, just a few months before the end of the war. While it was one of the last receiving stations to close, some of the internment camps wouldn't close until 1920, with the deportation of those internees deemed "non-desirable".

The entire episode is a blot on Canadian history; a betrayal of the promises made to these immigrants by a country that invited them in with open arms. Yet the story of the persecution of these so-called 'enemy aliens' didn't end with the closing of the camps. For decades afterwards they faced racism and discrimination from a society that regarded them with contempt. The effects on their communities would echo down through the generations.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

1. The Niagara Frontier

1. "The acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching," *National Park Service*, (2016), online.

2. The Fenian Raids

1. Katja Wustenbecker, "German-Americans During World War I," *Immigrant Entrepreneurship,* Sept. 19, 2014, last updated Aug. 22, 2018, online.

2. John Grodzinski & Peter Vronsky, "Fenian Raids," *The Canadian Encyclopedia,* March 3, 2014, online.

3. Peter Wronski, "Combat, Memory and Rememberance in Confederation Era Canada: The Hidden History of the Battle of Ridgeway, June 2, 1866," PhD Thesis, (University of Toronto, 2011), ii.

4. Wronski, iii.

5. Wronski, 6.

6. Wronski, ii.

3. The Militia's Armoury

1. "Niagara Military Museum Exhibits," *Niagara Military Museum,* 2021, (online), 11.

2. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 53.

4. Reservists, Spies, & the Destitute

1."Sensational Sequel to arrest of Austrians," *Niagara Falls Evening Review,* October 19, 1914, online.

2. "Two Men arrested following banquet at Niagara Falls, Ont.," *Brandon Daily Sun*, December 11, 1914, online.

5. Invasion Rumours

1. "Arrested by Wellend Canal Men," *Morning Star,* August 8, 1914, online.

2. "Enough Irish Policemen in Buffalo to Stop Invasion," *Toronto Daily News,* November 20, 1914, online.

3. "Plot is Unearthed to Invade Canada," *Toronto Daily News,* February 7, 1916, online.

4. "Danger of German Raid on Fort Erie is Very Remote," *Toronto Daily News,* November 2, 1914, online.

6. German Plots

1. Alun Hughes, "Terrorist Attacks on the Welland Canal," *Newsletter of the Historical Society of St. Catharines*, (Alun Hughes, 2008) 10.

2. Martin Kitchen, "The German Invasion of Canada in the First World War," *The International History Review.* VII, 2, (May 1985, pp. 175-346), 249.

7. Friend or Foe?

1. John Mrmak, "The Plaque on the Stone: Niagara Serbs Remember the Internment," *Voice of Canadian Serbs,* September 25, 2014, online.

2. "Spy Joined Army at Brantford," *Niagara Falls Evening Review,* July 31, 1915, online.

3. "Pole Arrested as Alien Enemy, *Ottawa Journal,* November 26, 1915, online. 4. "Austrian Reservist Killed," *Toronto Daily News,* June 10, 1915, online. 5. "Sensational Sequel to Arrest of Austrians," *Niagara Falls Evening Review,* online.

6. See On This Spot's tours in Halifax (Locked in the Citadel), Toronto (Internment at Stanley Barracks), and Lethbridge (Horror at Exhibition Park) for examples.

8. Fighting for Canada

1. Peter Broznitsky, "For King, not Tsar: Identifying Ukrainians in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1918," *Canadian Military History* 17, 3 (2008), 21.

2. Broznitsky, 21.

3. Broznitsky, 35.

4. Lubomyr Luciuk, "Filip Konowal, VC," *The Canadian Encyclopedia*, April 24, 2015, online.

Bibliography

Hughes, Alun. "Terrorist Attacks on the Welland Canal." *Newsletter of the Historical Society of St. Catharines*. Alun Hughes, 2008. https://brocku.ca/social-sciences/geography/wp-content/uploads/sites/152/Terrorist-Attacks-on-the-Welland-Canal.pdf

Grodzinski, John & Vronsky, Peter. "Fenian Raids." *The Canadian Encyclopedia.* March 3, 2014. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fenian-raids

Kitchen, Martin. "The German Invasion of Canada in the First World War." The International History Review.* VII, 2, May 1985, pp. 175-346.

Kordan, Bohdan S. *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience.* Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Mrmak, John. "The Plaque on the Stone: Niagara Serbs Remember the Internment." *Voice of Canadian Serbs.* September 25, 2014. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/2014-09-25-VCS-The-Plaque-on-the-Stone.pdf

Luciuk, Lubomyr. "Filip Konowal, VC." *The Canadian Encyclopedia*. April 24, 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/filip-konowal

*National Park Service*. "The acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching." 2016. https://www.nps.gov/articles/a-mere-matter-of-marching.htm

*Niagara Military Museum.* "Niagara Military Museum Exhibits." 2021. https://issuu.com/niagara_military_museum/docs/exhibits_at_niagara_military_museum

Wronski, Peter. "Combat, Memory and Remembrance in Confederation Era Canada: The Hidden History of the Battle of Ridgeway. June 2, 1866." PhD Thesis. University of Toronto, 2011.

Wustenbecker, Katja. "German-Americans During World War I." *Immigrant Entrepreneurship.* Sept. 19, 2014. Last updated Aug. 22. 2018. https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/german-americans-during-world-war-i/

**Newspaper Articles**

"Arrested by Welland Canal Men." *Morning Star.* August 8, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1914-08-08-MSTAR-Arrested-by-Welland-Canal-Men.pdf

"Austrian Reservist Killed." *Toronto Daily News.* June 10, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1915-06-10-TDS-Austrian-Reservist-Killed.pdf

"Danger of German Raid on Fort Erie is Very Remote." *Toronto Daily News.* November 2, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1914-11-02-TDN-Danger-of-German-Raid-on-Fort-Erie-is-Very-Remote.pdf

"Enough Irish Policemen in Buffalo to Stop Invasion." *Toronto Daily News.* November 20, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1914-11-20-TDN-Enough-Irish-Policemen-in-Buffalo-to-Stop-Invasion.pdf

"Pole Arrested as Alien Enemy. *Ottawa Journal.* November 26, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1915-11-26-OJ-Pole-Arrested-as-Alien-Enemy.pdf

"Plot is Unearthed to Invade Canada." *Toronto Daily News.* February 7, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1916-02-07-TDN-Plot-is-Unearthed-to-Invade-Canada.pdf

"Two Men arrested following banquet at Niagara Falls, Ont.." *Brandon Daily Sun*. December 11, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1914-12-11-BDS-Two-Men-Arrested-Following-Banquet-at-Niagara-Falls.pdf

"Sensational Sequel to arrest of Austrians." *Niagara Falls Evening Review.* October 19, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1914-10-29-NFER-Sensational-Sequel-to-Arrest-of-Austrians.pdf

"Spy Joined Army at Brantford." *Niagara Falls Evening Review.* July 31, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/23/1915-07-31-NFER-Spy-Joined-Army-at-Brantford.pdf