Walking Tour

Horror at Exhibition Park

Lethbridge's Internment Camp

Elyse Abma-Bouma

With war comes suspicion, turning neighbour on neighbour and country on communities. During the First World War, Austro-Hungarians became the scapegoat for Canadians' unease. Widespread fear of these people prompted the government to include certain provisions in the War Measures Act that stripped the rights from immigrants from enemy countries, and laid the groundwork for a system of mass surveillance and internment camps.

Spread across the country (particularly in the National Parks), internment camps were favoured by the federal government, government ministries, and many municipalities as a solution to deal with so-called "enemy aliens", and keep close tabs on their actions.

Opening on September 30, 1914, the Lethbridge internment camp was located on the Expo Grounds, and interned around 600 men who were primarily of Ukrainian and German descent.

The Lethbridge internment camp gained a reputation for being poorly run, with ill-disciplined guards. When neutral diplomats and former internees spoke out about the brutality and abuses they saw at the camp, it caused Canada major international embarrassment. It was one of the few Canadian internment camps where reports of prisoner torture were substantiated by neutral diplomats.

The camp would operate until the end of 1916, when the internees were either paroled to work in various industries, or transferred to one of the few remaining camps that then remained open.1

Route

In this tour we will walk the grounds of Exhibition Park, starting at the main parking lot, and continuing towards the racetrack. The internees were housed in small, cramped chicken sheds and barns near the racetrack. One of them survives to this day.

1. What the Ground Knows

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

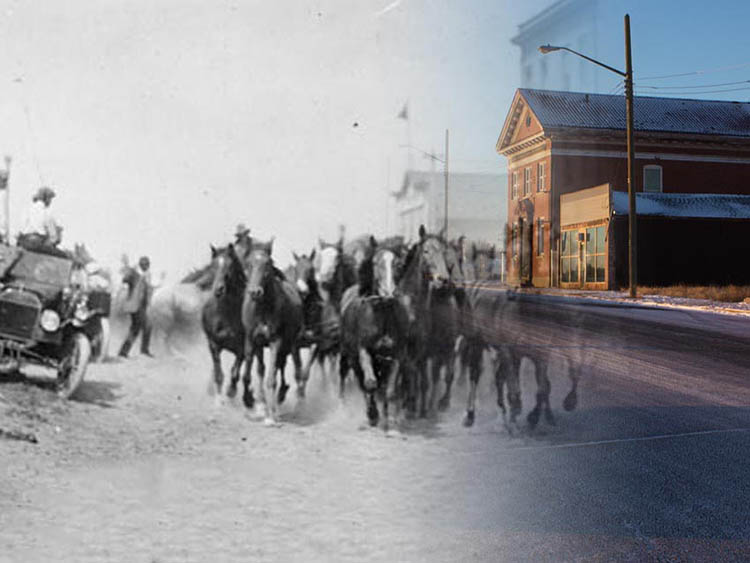

ca. 1900s

Looking around the expo grounds today, you'd never suspect that this was once an internment camp for German and Austro-Hungarian enemy aliens during the First World War. As we go through the tour you'll also notice that the historic photos do not feature the camp or internees at all. Photos and records of the Lethbridge camp are sparse.

* * *

Through the efforts of historians, recollections from the living descendants of internees, and organizations like the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund, we can piece together this dark chapter in Canadian history.

Studying these camps is further complicated by the fact that many of these sites were torn down or repurposed. Some camps, such as the Halifax Citadel, were based out of preexisting military forts, but the majority were built by the internees themselves, and swiftly dismantled when the camp closed. Unlike the Halifax Citadel or Fort Henry at Kingston, camps that were built in baseball diamonds, wilderness clearings, soccer fields, and expo grounds such as these, aren't easily converted into exhibits. However, the Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund has worked tirelessly to erect plaques and monuments at internment sites across the country so these locations are not lost to time.

Looking at the expo grounds today, it is difficult to imagine the scope of the camp, where the buildings were, and how the internees spent their days. From the limited records and photos that exist, we know that the chicken barn, which still stands today, is one of the buildings where internees were held, but there is little else that remains here from this period in history.

2. The Internees

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

ca. 1900s

The story of internment begins with the arrival of central and eastern European immigrants to the Canadian West in the preceding decades. After a long and sordid history of land disputes between the Indigenous peoples of the prairies and the British Crown, Canada began to parcel out land for European settlement. This displaced the Indigenous peoples of the prairies, who were herded onto tiny reserves, where an astonishing number of them starved. These included the Siksika (Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Piikani (Peigan), Stoney-Nakoda, and Tsuut’ina peoples, just to name a few.1 The Canadian government wanted hardy agriculturalists to settle and farm the prairies, and aggressively advertised free or extremely cheap land to potential settlers in eastern Europe.2

It is a tragic irony that the eastern Europeans, who were encouraged to settle here by the Canadian government, would soon be persecuted in ways that bore striking similarities to the persecution of the Indigenous peoples upon whose land they were settling.

* * *

"When I speak of quality I have in mind, I think, something that is quite different from what is in the mind of the average writer or speaker upon the question of Immigration. I think a stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children, is good quality."3

Though an ultimately problematic characterization of Eastern Europeans, it was this sentiment that contributed to the wave of Austro-Hungarian immigration prior to the First World War. During this period parts of what are today 12 separate nation-states, were under the domain of the sprawling and polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire. By far the largest proportion of Austro-Hungarian immigrants who settled on Canada's prairies were from the empire's frontier provinces of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia. Today these are regions of today's western Ukraine, and the vast majority of immigrants from those areas were ethnic Ukrainians.

While Ukrainian and other Austro-Hungarian immigrants were welcomed by the Canadian government, many Canadians were less enthusiastic about the new arrivals:

"How are we going to maintain in this new land, which we proudly call 'the Great Britian Beyond the Seas,' those principles and usages and ideals that have made Great Britain so strong and prosperous and influential? We have inherited the genius of the Anglo-Saxon race, a genius that is the product of the thought and toil of a thousand years." 4

This statement by a Presbyterian reverend reflected a tone employed by many British Canadians at the time. Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire settled on the prairies from 1896 to 1914. According to the 1911 census, immigrants from those nations amounted to nearly 14% of Canada's total population of seven million. These immigrants frequently settled in bloc communities where they could continue their language, culture, and traditional practices. Many also settled in the cities, and became an important part of the proletarian working class and often aroused the ire of the Anglo-Canadians who they worked alongside.

As one British writer noted:

"When a Ukrainian went into construction business…he trailed a small army of other Ukrainians behind him…It was the same with the Germans."5

3. Resentment and Discrimination

1912-13

Discriminatory attitudes towards the Ukrainians and Germans in Lethbridge were prevalent even before the war broke out, but war supercharged these tensions. Many Canadians, including government officials, escalated their distaste for Ukrainian immigrants from merely inferior, to an outright threat. In a sense, many Canadians were waiting for an excuse to ostracize Austro-Hungarian nationals—even those who had become Canadian citizens. The war presented them such an opportunity.

* * *

Failure to register could land you in an internment camp. Once they had registered, their movements were monitored and they had to report to the police for a regular interview. If during this interview, the 'enemy alien' was found to be unemployed or homeless, they would be sent to an internment camp.

The criminalization of unemployment and homelessness amongst enemy aliens was one of the most unfair and arbitrary aspects of the camps. 1914 was a time of economic recession and high unemployment. The situation for the 'enemy aliens' was made worse when many thousands were spontaneously fired from their jobs by employers who saw it as their patriotic duty, and at the demand of "Allied" workers who saw enemy aliens as competition for scarce jobs.

Since there was almost no social safety net at the time, the government feared that the streets of Canadian cities would soon be overrun by homeless, starving 'enemy aliens.' Britain had ordered Canada not to let any of these 'enemy aliens' leave the country, lest they somehow make it back to Europe to sign up in the German and Austro-Hungarian armies. So the government tried to tell itself it was acting benevolently by putting these people in internment camps. As the justice minister would later say: "We interned these people because we felt that, saying to them 'You shall not leave the country,' we were not entitled to say, 'You shall starve within the country.'"4

In the internment camps they could be put to work for 25 cents a day (about 1/14 the average wage for free labour), working in appalling conditions on jobs that free labourers did not want to do. Some Ukranians found themselves in such dire circumstances that they would ask to be given work at a camp because the bare minimum of food and pay offered by the camps was better than starving on the streets. 1

The Lethbridge Camp was housed at the fairgrounds in town. Several of the buildings were temporarily repurposed for barracks and kitchen, including the chicken barns on the east side by the train tracks and another barn structure on the west side near the nursery. Prisoners worked on the grounds to upkeep the camp or were often taken off site for work projects.

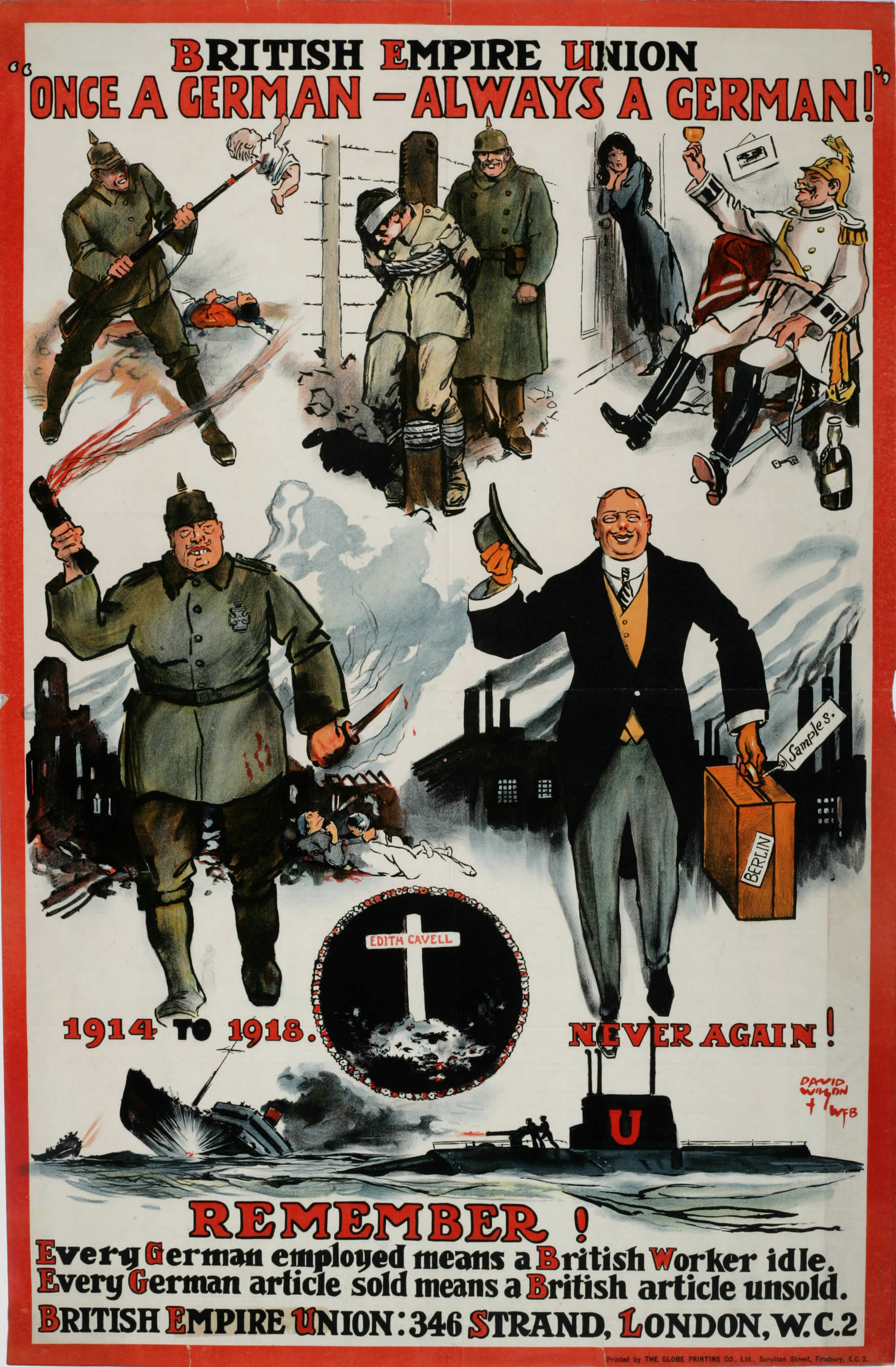

Most in Lethbridge turned a blind eye to the plight of the Germans and Ukrainians in the camp, while others fully supported their imprisonment. The reasons for detainment varied but were usually flimsy and arbitrary. Austro-Hungarian reservists were viewed with extreme suspicion as many thought their loyalty still laid with their mother country. In many cases, the Ukrainians were viewed as dangerous simply because their language, culture, and religion differed from that of British Canadians and they were often willing to do more dangerous work for lower wages. Posters like this one highlight the disdain and distrust many held towards 'enemy aliens', even for long after the war.

4. The Camp

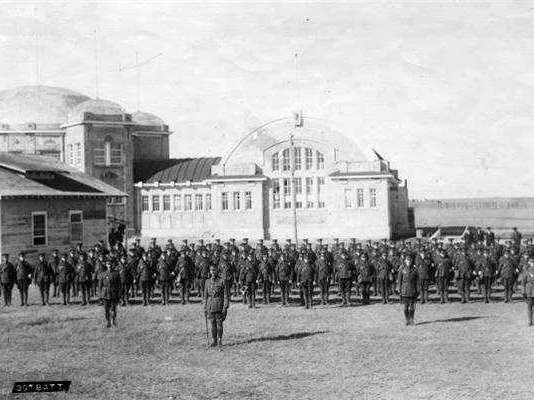

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

ca. 1915

In this photo of troops from the 39th Artillery Battery on parade on the Exhibition Grounds, you can also see at left part of one of the chicken barns that served as the internee barracks. At its peak, 300 prisoners were kept in this camp, and housed at this and several other barns. They were guarded by 60 soldiers who kept the prisoners working and contained.1

The camp's grounds spanned the area around the barn and was enclosed by barbed wire fencing. The surviving accounts from prisoners are limited, but there are enough to draw some conclusions about the conditions and people who were detained there. However, the accounts contradict each other and differ depending on whether the speaker was a guard or military officer (who tended to think the camp's conditions were excellent), or an internee (who tended to think the conditions were horrifying and dehumanizing).

* * *

Prisoners reported that the guards were abusive and violent towards them in many ways, including denial of food, beatings, bayonetings, prolonged solitary confinement, and torture. Of course the camp authorities denied these allegations.2

Initially, the Canadian government viewed Germans, Ukrainians, Turks, Hungarians, Austrians, Bulgarians, and a number of other nationalities as a uniform category of 'enemy aliens.' Yet each represented a distinct cultural group with different understandings of social class, and of politics. Almost all of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Turk internees came from the subordinate nationalities within those empires, and actually saw the Austrian and Ottoman governments as hated oppressors. Often they had come to Canada to flee persecution by these governments. The most galling example of this were the hundred or so Armenians in Brantford, who were interned as Turks. At that same time, in 1915, the Ottoman state was carrying out a genocide of Armenians, that is thought to have killed around a million people. In the same way, the many Ukrainians in Lethbridge, who fiercely hoped for their own countries emancipation from Austrian rule.

These national rifts caused tensions amongst prisoners, most commonly with altercations between Austro-Hungarian and German internees. These altercations resulted from the Austrian prisoners blaming Germany for the war and their current predicament. Thus the Canadian government decided to start segregating the camps by nationality to the extent that Germans were separated from the other internees.

The government also divided the prisoners into first and second-class. Second-class prisoners were made to chop firewood, carry water and generally fend for themselves on top of the other labour assigned to them. First class prisoners, on the other hand, were not forced to work, and allowed privileges such as better living quarters and the opportunity to hire second class prisoners to work on their behalf. Due to stereotypes and class prejudices, Austro-Hungarians were often placed in the second class category, whereas Germans tended to be first-class prisoners.3 In the end most of the Austrian second-class prisoners would be sent to forced labour camps at places like Banff and Jasper National Parks, whereas the Lethbridge camp became predominantly reserved for first-class German prisoners.

5. Differing Fates

1912

When the Lethbridge internment camp was established in 1914, Austro-Hungarians and Germans from all of southern Alberta were sent there if they were unemployed, unhoused or were deemed to be of some threat. As the war dragged on it was increasingly Germans who were detained at the Lethbridge camp.

Ukrainians, Poles, Croatians, Slovaks, and other members of the subject nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were transferred from Lethbridge to forced labour camps in places like Banff, where they endured appalling conditions and abuse while working to improve Canada's national parks.

* * *

German prisoners however, were often reservists in the German armed forces who had immigrated to Canada before the war. They were often aware of their rights under the Hague Convention. This international agreement limited what governments could subject prisoners of war to and mandated standards of living for them. German detainees made clear that they not only knew what they were entitled to, but would file complaints about their treatment with diplomatic go-betweens from neutral countries. Reports of mistreatment could result in retaliation towards Canadian and British prisoners of war in Germany. The same could not be said for Ukrainians in Canada, for whom the Austro-Hungarian government cared little. As a result, German prisoners were treated better than their Ukrainian counterparts.1

Once most of the Ukrainian prisoners were transferred to forced labour camps in the Rockies, there were reports of German internees being allowed privileges such as golfing and escorted excursions into the town of Lethbridge. This was much to the dismay of Lethbridge residents who preferred that prisoners were kept out of sight and out of mind. Captain J.A. Birney, commandant of the Lethbridge camp confirmed that these privileges were extended to only two prisoners. The experience of such privileges were quite rare and the response from townsfolk shows us the attitude towards Germans and Ukrainians at the time.2

6. Brutality

1912-13

Enforcing discipline at the camps was left to the guards, who weren't always prioritising the welfare of their charges. Few outside the camps concerned themselves with the internees' well-being either, due to the growing resentment towards Eastern Europeans in British Columbia and Canada as a whole.

In 1915, the Lethbridge camp drew international attention when a letter was published by the Chicago Tribune with accounts of abuses by guards; the most noteworthy one being that of a prisoner who was beaten by a sergeant and bayoneted in the upper legs and back, then brought to an office and chained.

* * *

"At the end of October, 1914, one Fritz Mathias, Hungarian, was condemned to carry stones with closed hands on account of a sarcastic criticism. Jollman Curke was beaten until blood came, innocent, through misunderstanding.

"Hans Schulz had his ears boxed and was chained and pulled up on chain on account of a haircut. Bringendatt complained about bad butter and was therefore chained.

"Ivanichatz, a Galician [Ukrainians were known as Galicians at the time], complained about his torn shoes and would not stand in the water and was therefore chained and pulled up on same.

"Imprisoned on bread and water on account of refusal to work out of doors: Three days, Klingenstein. One day, Hill. One day, Olsen. Four hours, Hulsman, without breakfast, on account of refusal to sign blank paper."1

Outraged at the accusations, the camp's commandant Captain Birnie and General Otter (overseer of the national internment operations) went through the accusations with the Lethbridge Daily Herald, refuting each allegation.

In regards to Fritz, Captain Birnie said "[I] was not there at the time but believ[ed] the man was deservedly punished for some offense." As for Jollman Curke, Birnie stated:

"This evidently refers to Solomon, a Turk…[he] had been acting strangely and suddenly became insane one day, attacking and severely wounding one of his fellow-country men, it being necessary for the guard to use force in overpowering him. The Turk is now in the asylum at Ponoka."

"[Hans Schultz] was formerly a teacher in a Calgary college, a professor who had long hair. The rule of the camp is that the hair must be cut short. This man not only refused to have his hair cut, but actually fought the barber when he got into the chair. He was handcuffed and made to hold his hands above his head for an hour."

As for Bringendatt, Birnie thought that this was probably a reference to Bringenwalt, as prisoners who were "found actually destroying pound after pound of butter, and was given the same punishment as Hanz Scultz."

In addressing the fate of "the Galician," Birnie admitted the claim was "substantially correct" because he refused to work and the s ame was for the others who were imprisoned and denied food.2

Though this article was meant to set the record straight, it is clear that Captain Birnie was preoccupied with trying to offer his take on the events, which would have been more well received by readers of the paper because of his position of authority. Notably, however, Birnie admitted to most of the accusations, finishing by saying "Occasionally [I am] compelled to use a certain amount of force."

These non-denial denials were widely published in the Canadian press and depicted as complete and utter exoneration of the conduct of the camp's officers and the guards. Regardless of how the denials were framed, they still demonstrated that the Lethbridge internment camp was indeed staffed with abusive guards who quickly resorted to violence in response to insubordination, and also were not hesitant to use the torture technique of strappado. Strappado is the practice of tying a man's hands behind his back, and then suspend him by his hands till his feet are barely touching the ground.3

Despite Otter and Birney's official denunciation of the accusations in the Canadian press, and Otter's confident public assurances that conditions in the camps were excellent and in keeping with Canada's international and humanitarian obligations, in private he took quite a different tone.

A neutral American diplomat wrote to Otter demanding an explanation for the many complaints of internee abuse he had heard when visiting the Banff camp. Otter replied:

"The various complaints made to you by the prisoners as to the rough conduct of the guards, I fear, is not altogether without reason, a fact much to be regretted and, I am sorry to say, by no means an uncommon occurrence at other Stations."4

As for Commandant Birney, Otter was embarrassed by the reports of strappado happening under his watch, and wrote of him: "a repetition must not occur… if a more close supervision cannot be exercised over the officers and men of his command… the good name of Canada [will be] brought to a level with the Huns." 5

The embarrassment caused by Birney's poor camp administration would soon cost him his job.

7. Escapes

ca. 1920s

As you may imagine, the prisoners resisted the abuse, even going so far as to try and escape. Both German first-class prisoners, and Austro-Hungarian second-class prisoners, concocted remarkably daring escape plans. A June 1916 article in the Lethbridge Daily Herald wrote:

"So far nothing has been learned of the two prisoners who escaped from Camp No.2 last week. Their getaway was well planned. They had just come in from exercise on the race track and filed into the gate of the compound. The [guard] in charge had failed to post his men on their beats about the camp before sending the prisoners in. The result was that the two Germans walked right through the sleeping quarters and jumped the fence at the back taking a chance that the guard would not be there yet. They guessed right and beat it off north to Hysson's bottom from which point all trace of them was lost."1

This particular escape was the final straw for General Otter, who had grown tired of the constant stream of embarrassments that Captain Birney's camp adaministration had led to. He fired Birney and replaced him with one Major Date, a Montreal businessman who was a no-nonsense disciplinarian. Date had become something of a fireman for Otter, who shuttled him from camp to camp, relieving commandants whenever there were too many escapes, or too many reports about the brutality of the guards got out. As the Lethbridge Daily Herald wrote, "he has been in charge of other camps and hopes to be able to handle the situation here."2

* * *

"As soon as the frost was out of the ground, work began. Near the centre of the sleeping section of the camp…a portion of the floor large enough for a man to crawl through was sawed out by a saw made out of a butcher knife from the culinary department…A hole was sunk to a depth of 4 and a half feet and plenty large enough for a man to work comfortable in…In the dead of night a working party of two or three would slip under the floor and commence operations. One man would dig and load the earth removed into a box on a little sled which was drawn back by means of a rope which had been braided out of all manner of strings, ribbons, and bits of cloth…With no suspicion that any attempt of the kind was in progress, the working parties went out every night and extended the tunnel to the limit." 3

The tunnel was worked on in secret for months, according to authorities. The internees dug the tunnel using tools they constructed themselves from scrap scavenged from camp, such as tin cans, string and scrap wood. The tools consisted of digging implements, mallets, a tamper, auger, and most impressively, a functional ventilation fan similar to those used in mines. A former coal miner, whose knowledge was indispensable for the operation, built the fan directly under the guards' supervision, after convincing them it was merely a hobby.

They planned every aspect of the escape carefully; they made careful measurements to make sure they ended up outside of the wall and to remove the soil without notice. However, only six prisoners managed to escape, and they were never recaptured. Fortunately for the guards, the seventh man got stuck—apparently he was a portly fellow. He was apparently stuck so badly that his fellow internees had to give up trying to pull him through, and sheepishly requested help from the guards to extricate him. If that hadn’t happened, who knows how many of the prisoners could have successfully escaped? The papers seem to think the guards would have awoken to an empty camp.

Prisoners continued to escape from Lethbridge, even with Major Date in charge. The frequent escapes helped contribute to the closure of the camp in late 1916.

8. William Perchaluk

In the two years this camp was in operation, over 600 internees passed through its gates. Many of the stories of these men are lost to time. Few kept records or wrote memoirs of their experiences, and the government had little interest in most of them after their release. The biographies of some of these men have been pieced together, and help illustrate the tragic pointlessness and cruelty of Canada's First World War Internment Operations. One example is the story of William Perchaluk.

* * *

William was part of the first group of internees from Lethbridge to be moved to the Castle Mountain internment camp. As we have seen in our Banff tour, the conditions at the Castle Mountain and Cave & Basin camps in Banff were appalling and intolerable.

Fortunately for Perchaluk, he was one of the first to be paroled from the internment camp as he was deemed "non-dangerous" and released to go work at the Canmore Coal Company, where he laboured in the mines. Mining was difficult and dangerous work, but it was even more difficult for William due to the fact that he had a serious lung condition that was aggravated by the coal dust and poor ventilation.

On June 26, 1916, William Perchaluk was granted leave to Calgary. While in Calgary, he enlisted in the military. Two days before he was set to leave for France, a former guard recognized him and had him arrested. At the time of his arrest, he was wearing his full uniform.1

William knew that he would be sent back to Castle Mountain. Rather than suffer through that experience again, on December 5, 1916, William used his puttees to hang himself in his cell.

His autopsy showed that his lungs were "darkened from coal smoke and dust." When no one stepped forward to claim his body, government departments bickered over who had to pay for the burial: internment operations or the military. William was not the only internee to suffer unimaginably, or to choose death over imprisonment, but his heart wrenching story highlights the despair that many felt during their internment and the failure of officials to provide adequate care to those in their charge.

William was eventually buried in Calgary and given the kind of headstone reserved for those who have died in Canadian military service.2 His is the only military headstone for a Canadian serviceman who was also an internee.

9. Families on the Outside

ca. 1915

Internment applied almost exclusively to men of Austro-Hungarian or German descent who were of eligible age for military service. While women, children, and the elderly were rarely interned, internment deprived these people of their sons, brothers, husbands, and fathers, and left them to fend for themselves in a harsh and cruel world.

In the early 20th century, men were usually the primary providers for the household. So, with their menfolk interned for an indefinite length of time, their families were left destitute and with no source of income. Many women tried to find employment, but few industries welcomed female workers in the early years of the war (something that would change by 1916-17). Even those that did hire women rarely hired enemy alien women (something that would take much longer to change). The families that were torn apart by internment were given little aid by the government.

* * *

"My condition here is very poor. You know very well that they do not want to support me with food and fuel, and I am in trouble in regards to the rent. I haven't any money to pay the rent, and the landlord doesn't want to keep me any longer in the house… I don't know what I shall do. I was in the City Hall asking for support for myself and for my child. They sent me to the Government Office and they told me to go to work and give my child to the creche. Now I write you to ask you what I shall do. Shall I give our dear child to a creche - or not."1

The Mudry family faced a horrifying choice: give up their child to earn a meagre wage or starve, since Mr. Mudry was imprisoned and unable to help his family. This situation wasn’t unique to the Mudry’s - families across Canada faced impossible choices when their men were interned.

10. Forgetting & Remembering

ca. 1915

The Lethbridge internment camp closed on November 11, 1916. Officials dissolved the camp primarily because it was poorly run and escapes were regular occurrences. "Non-dangerous" internees were paroled to work in strategic industries, since by 1916 the job shortage had turned into a huge shortage of labour. Those prisoners deemed dangerous or "undesirable" were transferred to other camps (Primarily in British Columbia and at Spirit Lake, Quebec). There they would remain for the rest of the war. Some would never be released back into Canada, but deported back to Europe in 1920.1

* * *

"As for reaping the advantage, the bulk of it goes to the enemy foreign element. If these men, by reason of their standing, cannot be conscripted, and, as stated, are taking advantage of the situation which their predominance gives them, then it is high time that this class of labour should be conscripted, and contribute to the war by working at a wage, in true measure of the value received, without being placed in an envious position in the eyes of those who have already of their free will been called away to war."2

With the economy suffering due to the shortage of labour, it was thought by some that internment was a waste of resources and the enemy aliens would be better used working wage jobs to stimulate the economy.

With the closure of the camp, it quickly began to fade from the public consciousness. News of escapes and changing guards kept the camp in the newspapers while it was open, but afterwards the dark history of the camp faded from thought. As a result, few people today are aware that hundreds of men were stripped of their rights and interned on this exhibition ground a little over a century ago.

Even the families of survivors struggle to preserve their history. As one descendant of a Lethbridge internee recounts:

"When we [feel] in danger with no chance of escape. What we do is make ourselves disappear… Like chameleons, we blend into the world around us, into the very thing that threatens us, in order to protect ourselves."3

Sharing these memories can be difficult for the communities and families because of the trauma or loss they experienced. Many of them chose to repress their memories and hid the details of their experiences even from their children. Many of these men who survived chose to keep their heads down and soldier on with their lives the best they could after being released.

This is a dark chapter of Canada’s history, making it equally important to preserve. Camps like those at Lethbridge are particularly at risk of being forgotten as there is little remaining here as a reminder. Losing the history of these sites robs us of the chance to honour the strength of a community that persisted despite imprisonment, xenophobia, discrimination, and hate, and also to mourn those that were lost before their time.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

- 1. Weistra, Benjamin. "Internment 100: The Lethbridge internment camp Story." Ukrainian Canadian Congress Alberta. Published October 6, 2020. [Video]

2. The Internees

1. Tesar, Alex. "Treaty 7." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published August 19, 2016; Last Edited November 06, 2019.

2. Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914." Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. January 28, 2022.

3. Only Farmers Need Apply: Sir Clifford Sifton, “The Immigrants Canada Wants,” Maclean’s magazine, April 1, 1922, pp. 16, 32-4.

4. Carter, Sarah. Imperial Plots. University of Manitoba Press (Winnipeg, MB). 2016. 255.

5. Loewen, Royden & Gerald Friesen. Immigrants in Prairie Cities. University of Toronto Press (Toronto). 2009. 16.

3. Resentment and Discrimination

1. Smith, Denis. "War Measures Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published July 25, 2013; Last Edited March 13, 2020.

2. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press. 85-6.

4. The Camp

1. Lee, Isabella. "Lethbridge Internment Camp During the First World War." Galt Museum and Archives. Published July 10, 2018.

2. "Charges Published in US Against Prison Camp Here are Shown to Be Ridiculous." Lethbridge Herald. December 3, 1915. 5-6.

3. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press.141

5. Differing Fates

1. Avery, Donald H. "Internment (Canada)." International Encyclopedia of the First World War, 1914 to 1918 Online. Updated March 27, 2015.

2. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press,142.

6. Brutality

1. Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1915. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

2. Lethbridge Daily Herald, December 3, 1915. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

3. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man, 166-184.

4. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 170.

5. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 171.

7. Escapes

1. "Major Date Takes Charge Detention Camp Here". Lethbridge Daily Herald, June 19, 1916. As found on the Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

2. "Major Date Takes Charge Detention Camp Here". Lethbridge Daily Herald, June 19, 1916.

3. "Six German Prisoners Tunnel Their Way to Freedom". Lethbridge Daily Herald, April 29, 1916. As found on the Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

8. William Perchaluk

1. Weistra, Benjamin. "A Prisoner's Story." The Galt Museum and Archives, March 17, 2020. https://www.galtmuseum.com/articles/a-prisoners-story

2. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press.156.

9. Families on the Outside

1. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press. 156.

10. Forgetting & Remembering

1. "Lethbridge and Banff to Lose Camps." Blairmore Enterprise, October 27, 1916. Internment Canada. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/15/1916-10-27-BLENT-Lethbridge-and-Banff-to-Lose-Camps.pdf

2. Kordan Bohdan. No Free Man. McGill University Press. 222.

3. Semchuk, Sandra. The Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019. XLVI.

Bibliography

Avery, Donald H. "Internment (Canada)." International Encyclopedia of the First World War, 1914 to 1918. Online. Updated March 27, 2015.

Carter, Sarah. Imperial Plots. University of Manitoba Press, Winnipeg, MB. 2016.

Gagnon, Erica. "Settling the West: Immigration to the Prairies from 1867 to 1914." Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21. January 28, 2022.

"Charges Published in US Against Prison Camp Here are Shown to Be Ridiculous." Lethbridge Herald. December 3, 1915. 5-6.

Chicago Tribune, November 28, 1915. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

Lee, Isabella. "Lethbridge Internment Camp During the First World War." Galt Museum and Archives. Published July 10, 2018.

Lethbridge Daily Herald, December 3, 1915. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

"Lethbridge and Banff to Lose Camps." Blairmore Enterprise, October 27, 1916. Internment Canada. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/15/1916-10-27-BLENT-Lethbridge-and-Banff-to-Lose-Camps.pdf

Loewen, Royden & Gerald Friesen. Immigrants in Prairie Cities, University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, 2009.

"Major Date Takes Charge Detention Camp Here". Lethbridge Daily Herald, June 19, 1916. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

Only Farmers Need Apply: Sir Clifford Sifton, “The Immigrants Canada Wants,” Maclean’s magazine, April 1, 1922.

Semchuk, Sandra. The Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps, Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019. Ebook.

"Six German Prisoners Tunnel Their Way to Freedom". Lethbridge Daily Herald, April 29, 1916. Galt Museum and Archives Website: https://www.galtmuseum.com/exhibit/internment-in-canada

Smith, Denis. "War Measures Act." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published July 25, 2013; Last Edited March 13, 2020.

Tesar, Alex. "Treaty 7." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published August 19, 2016; Last Edited November 06, 2019.

Weistra, Benjamin. "A Prisoner's Story." The Galt Museum and Archives, March 17, 2020. https://www.galtmuseum.com/articles/a-prisoners-story

Weistra, Benjamin. "Internment 100: The Lethbridge internment camp Story." Ukrainian Canadian Congress Alberta. Published October 6, 2020. [Video]