Driving Tour

A Planned Community

Kitimat Takes Shape

By Natalie Dunsmuir

Kitimat is unique when it comes to Canadian towns. It was not a town that sprung up naturally but rather, the dream and plan of experienced and passionate town planners. Every aspect of Kitimat's original layout was carefully thought over with the goal of making the town a happy, peaceful, and productive place.

The Aluminum Company of Canada, or Alcan, built the town of Kitimat in the 1950s to be a place that would inspire workers of the nearby aluminum smelter to stay at their jobs long-term. They wanted neither a shack town nor a company town but an independent, thriving community that would attract families to the region. They hired a team of town planners, psychologists, scientists, and architects to attempt to create the perfect town.

In this walking tour through Kitimat's first neighbourhood, Nechako, we will dive into the philosophies that went into creating a completely planned town. In the first stop, at Kitimat's Public Safety Building on the edge of Nechako, we will look at Kitimat's first steps towards independence from the aluminum company that created it. Then, we will turn down Kingfisher Street and walk to the base of Oriole Street, the first street to be constructed in the new town. Here, we will learn about the town planner, Clarence Stein, and the many philosophies that underlay the creation of Kitimat.

Stop three is farther down Kingfisher Street at the Nechako Centre, a shopping complex that was originally key to Kitimat's unique system of neighbourhoods. Here, we will discuss Kitimat's overall layout and the principles which went into the neighbourhood-centred design of the town. At stop four, located nearby at the United Church, we will talk about multiculturalism in Kitimat and how the town's diversity created a thriving community.

To reach stop five, follow the community walkway behind the church to the pedestrian underpass across from the Nechako Centre, where we will learn about Kitimat's unique, highly developed system of walkways and greenspace. Lastly, pass through the underpass to the far side of the Nechako Centre and learn about the lives of women and children throughout Kitimat's early years.

This project was created in partnership with the Kitimat Museum and Archives.

1. Company Town to Community

1956

This photo shows the opening ceremony in 1956 for the town's Public Safety Building with firehall. Officials, RCMP members, and guests gather in front of the building to celebrate its construction. The creation of municipal services such as firefighting, roads and highways, the school board, and a police force were a big part of Kitimat's early steps towards an identity independent of the Aluminum Company of Canada (Alcan).

* * *

"At Kitimat, the setting for a good life must be hewn out of the unknown wilderness. Pioneers must become old-timers bound to Kitimat by their love of the town and its unusual qualities."1

This "good life" was not compatible with the traditional concept of a company town. In these towns, which were fairly common at the start of the twentieth century, the company that provided employment also controlled the town. It owned the real estate and stores and ran the municipal council.

One of the assistant project managers of Kitimat, Frank T. Matthias, pointed out that "Life in a company town has an insidious psychological effect on people."2

In 1953, the town of Kitimat became the first in BC to be incorporated before a single resident lived there. A special act of the BC legislature was required, since incorporation usually involved the election of multiple landowners to a municipal government, and Kitimat only had one landowner at the time: Alcan.

To establish a town government, Alcan gave parcels of land to six of their employees so these men could legally be elected. The land was located on the delta and the conditions of the so-called "sale" forbid the new owners from building on it. It was to be held until the end of the council term, when it would be returned to the Company.5

Within a short time, Kitimat developed infrastructure and public services. The new government passed bylaws, elected a school board, signed a contract with the RCMP, bought the Haisla Bridge over the Kitimat River from Alcan, and worked to establish the medical and emergency services.

Alcan also sold off its real estate in the community. One company official was quoted as saying, "We're in the aluminum business. We don't want to be real estate agents. Not any longer than necessary."6 Alcan offered most of the buildings in the town up for private sale. To help their employees purchase these houses, they offered a unique mortgaging system.

The price for a house in Kitimat was around $14,000. The Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation granted a first mortgage to purchasers; Alcan granted a second. At the same time, the company offered monthly bonuses to every employee who bought or built a house in Kitimat. These employees were given $2.85 per $1,000 of the home's cost every month, or $39.90 a month for a $14,000 home. This was roughly the same as the second mortgage offered by the company: "Alcan writes the mortgage with one hand and pays if off with the other."7

All of this was done with the goal of reducing worker turnover. Alcan had worked hard throughout the construction process to gain a reputation as a company of the future, harnessing the wilderness to create the "metal of the future". The last thing it wanted was to be tied to the company towns of the past. And so, Kitimat's unique identity was born.

2. Kitimat's Town Planners

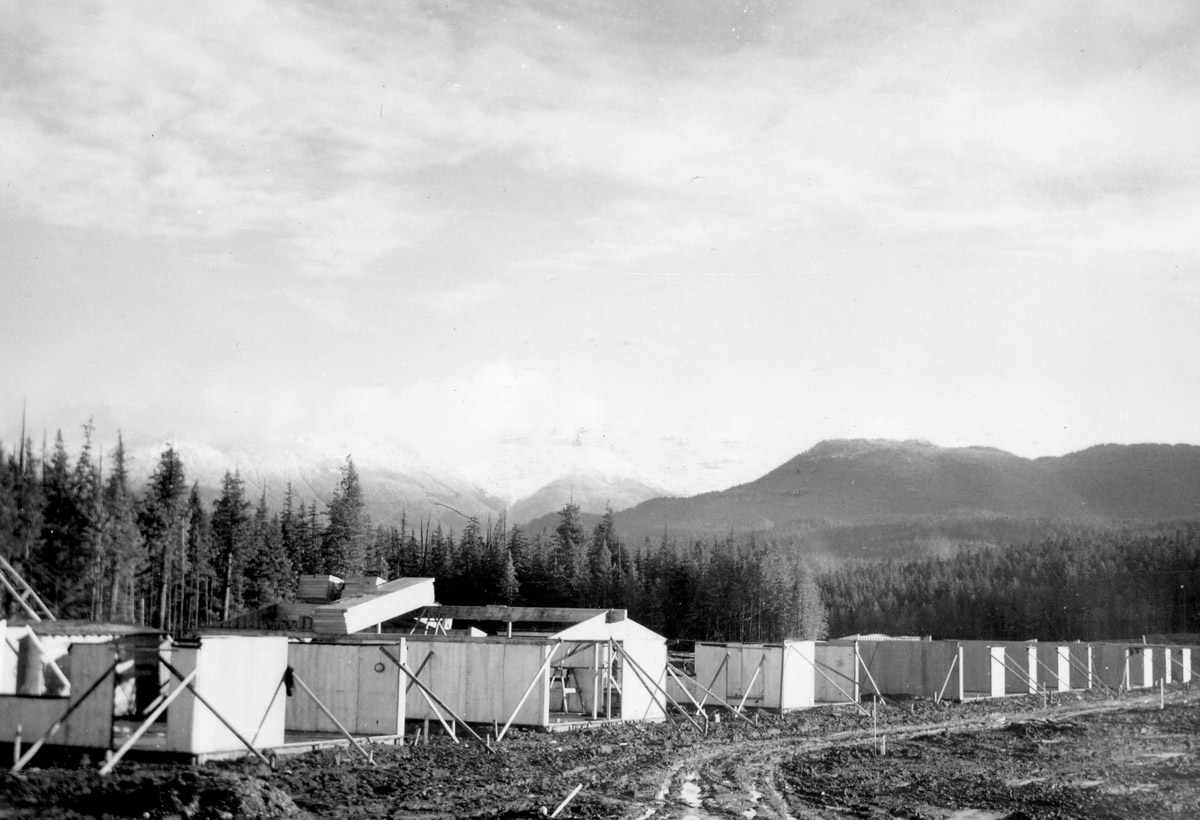

1953

This picture shows Oriole Street, the first street built in Kitimat, during its initial construction. Note all of the mud. Mud features prominently in the memories of early settlers when they recall Kitimat's early days. No matter how intricate and idealized the plan for Kitimat's design was on paper, the process of transferring it to reality was long, complicated and, above all, muddy.

The philosophy and academic thought that went into Kitimat is astounding. Everything was considered. The dreams and ideals of the town planners could hardly fit into Kitimat, with its wild nature, hilly terrain, and people with their own plans. But that didn't mean the town planners weren't going to try.

* * *

In the US, the town of Radburn, in New Jersey, was built to separate car and pedestrian traffic to avoid accidents. In Maryland, US, the city of Greenbelt utilized ideas from both England's Garden Cities and from Radburn. Different types of traffic were separated and the town was built within a strip of forest and rural land. In this city, greenspace was also of central importance, with parks and recreation areas built into the layout of the town.1

Radburn and Greenbelt had more in common than their traffic patterns: both were designed in part by famed American city planner and architect Clarence Stein. And in the 1950s, Stein was given a new challenge: Kitimat.

Alcan had big dreams for Kitimat. They planned to gradually expand the smelter and, in doing so, expand the town to a population of 50,000. Kitimat was meant, at one time, to be one of the largest cities in BC, third only to Vancouver and Victoria. This did not come to pass, and the town currently has a population of around 8,000.

Kitimat's early town planners were determined to build a thriving utopia, everything in it planned well. During the process, a sociologist wrote that adequate planning could solve "the problem of cross wives frustrating their husbands."2 In the eyes of the town planners, a good life came down to planning.

The same ideals of traffic separation and greenspace inclusion were utilized in Kitimat as in Stein's earlier towns. Everything from the layout of the streets to the design of the houses was carefully planned. Main bedrooms were located on the opposite side of the house from children's play areas with the intention of allowing men who worked nights at the smelter a chance to rest in silence during the day. The town was positioned to prevent smoke from the industrial areas from blowing over it. On streets where snow might pile up, hedges were planted to act as snow breaks.3 Even the empty, unused spaces were planned. Alcan hired a sociologist, Lois Barclay Murphy, to tackle the task of making sure Kitimat's residents would be happy in the town. Murphy pointed out that children need wild space to explore and grow, and even suggested that they need building materials such as bricks, boards, tiles and pipes for forts and toys. Kitimat's architects purposely planned for the inclusion of out-of-the-way spaces where building litter and debris could be left.4 Yet despite all of this planning, the experts in charge of Kitimat were sometimes out of touch with the environment they were working in. They were city people, unused to wild weather and wild spaces. The houses, designed in California, were not built for Kitimat's weather. One house design had an uninsulated aluminum roof upon which the rain would thunder. Another had glass French doors in the living room against which six feet of snow would build up in the winter. A third design had a roof that leaked under the force of Kitimat's weather.5 Demonstrating this lack of connection between the town planners and the wilderness of Kitimat was one suggestion made during the planning process: that in this town nestled among the wild mountains, where bears, moose, and mountain goats roamed, a nature zoo should be constructed so that the children "could see real live squirrels."6 Needless to say, this plan was eventually scrapped. Kitimat's town plan had its flaws and its triumphs, creating a unique foundation on which Kitimat grew throughout the years. As one Alcan engineer reflected long after the town was built, "Kitimat is different. When it was built it had no hinterland. It exists as a result of a conscious decision by a few men… The founding of Kitimat did some good, some harm. Some things were done well, some badly."7

3. Kitimat's Neighbourhoods

1954

Although the oldest buildings of Nechako Centre, which once housed Coghlin Hardware, Shop Easy, Sheardown Coffee Cup, and other commerce, are vacant, other businesses continue. A thriving community centre still exists where Nechako residents can shop. There is a dry cleaner, tattooist, pizza place, corner store, barber and hair stylist, gym, theatre, and medical offices. This photograph shows the Centre during its construction in 1954, when the parking lot was being levelled and prepared for pavement.

The neighbourhood of Nechako was once intended to be the first of ten distinct Kitimat neighbourhoods. Each would be built with its own neighbourhood centre with walking paths throughout so that residents could reach these centres without ever having to share a road with cars.

* * *

The first houses in Kitimat were built on Oriole Street, and in September of 1954, a public auction was held for 118 building lots in Nechako, most centreed around the core area of the neighbourhood where you now stand. The lots were cheap on their own, prices ranging between $880 and $1050, but there was a catch: a house had to be built on the land within 18 months of the purchase.2 Still, families began to flood into Nechako almost as soon as the land had been cleared, eager to begin the creation of a brand new home. By the end of that first year, hundreds of new homes had been built.3

An early resident of Nechako described the neighbourhood during that first year of construction: "the Townsite - just a complete sea of mud in the fall of 1953... It was a sea of mud for darned near the next year until they got house #1 in there which was I think on Oriole Street. So they had the whole of [the Nechako] area cleared... and they had big fires and they burned up all the wood and everything."4

Each neighbourhood had more than just houses in it, of course. In an effort to create a community which appealed to families, the designers of Kitimat centreed each neighbourhood around a central "hub". The Nechako Centre where you stand is a central neighbourhood hub. The idea behind this design was that "No housewife will be more than a five-minute walk from a community shopping centre or baby clinic, and she will never have to push her pram across a busy street to reach them."4 Everything that was needed in daily life would be within easy walking distance. The Nechako Centre would act in part as a general store and gathering spot.

The town planners thought through each aspect of the neighbourhood concept, carefully calculating the ideal size of neighbourhoods in order to best create this type of community hub. Neighbourhoods had to be big enough to sustain their community centres, but not so big that the centre was not within easy reach of even those living on the outskirts.

"Starting from a norm of about 1,500 families and distances not to exceed ½ mi from the centre, we were less concerned with pinpointing an exact standard than with setting the permissible extremes of deviation."6 The optimum neighbourhood number was set as 1,200 families, while the minimum was 500 families and the maximum 1,800 families.

4. A Multicultural Kitimat

1964

This United Church was one of many religious houses of worship which were established in Kitimat during the 1950s and 1960s. From the very beginning, the town was an extremely diverse and multicultural community, and its churches reflected this: there were 13 religious congregations in Kitimat by 1959, and seven had constructed their own buildings. The congregation of this United Church was made up almost entirely of immigrants 1, and its members knew only small amounts of English.

* * *

Early Kitimat had large populations of German, Italian, Portuguese, and Greek citizens, and these were later joined by Sikh, Finnish, Chinese, and Filipino communities. Between 1956 and 1964, over 1,500 people received their Canadian citizenship while living in Kitimat.3 And all of these diverse communities were having to adapt to the same new ways of life, the same peculiarities, challenges, and joys that came with living in such a unique place. The diversity of Kitimat was such that a popular saying in town at the time was, "If you want to study a foreign language, go stand at a bus stop."4

Of course, the language barriers did cause communication difficulties, and efforts by newcomers were made to learn English. Schools taught children the language, while community organizations held classes for adults. The Catholic Church was instrumental within the community for fostering English language skills, while the Anglican and United Churches tended to cross language divides less frequently. Few, if any, members of the United Church congregation spoke English.5

Unlike most diverse communities, Kitimat did not become geographically divided along cultural lines; there were almost no neighbourhoods dominated by a certain cultural or ethnic background. This was largely due to the way in which Alcan sold its initial housing. Houses were allotted to workers on a first-come-first-serve basis, street by street and block by block. Families took the first house that became available, regardless of where it was located or if it was near friends or relatives. A single street could be home to families from four or five different cultural backgrounds. The only street which broke this trend was Albatross Street, which was where management lived. Nicknamed "Brass Alley", it was dominated by Canadians and Americans with largely British backgrounds.6

For the most part, Kitimat's diverse communities lived in harmony, and the multiculturalism of the town enriched it. "It certainly broadened us as well, you know, because you are interacting with different kinds of cultures that you have a much more diverse attitude. Our kids who went to school were actually in the minority of kids that had English as a first language or had any understanding of English... How do you help those children learn in that kind of situation... I think that's probably one of [the] things Kitimat can be most proud of. It is that they managed that, and a lot of communities can't…"7

5. Kitimat's Famous Walkways

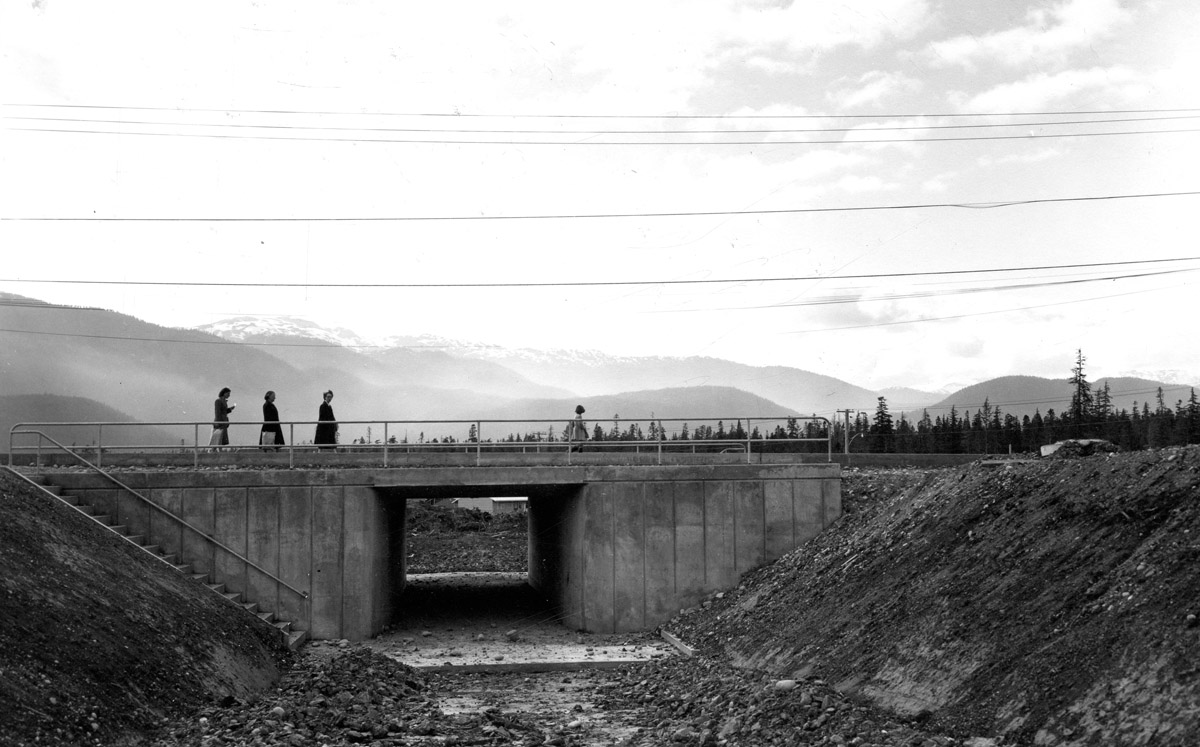

1955

This photo was taken shortly after this pedestrian underpass was constructed in the early days of Kitimat. In it, three women and a child walk across the top of the underpass, which is still rough and unpaved. The neighbourhood of Nechako is still in its early stages, muddy and empty of many of the buildings which were to come.

Walkways such as this one were key to Kitimat's design. Clarence Stein and the other members of the planning team wanted the city's residents to be able to get anywhere they needed without either getting in a car or being put at risk by cars. Vehicle and foot traffic would be completely separate where possible.

* * *

"Not only does this system offer safety for children (and to a small boy on a tricycle, a rolled curb between sidewalk and highway is no barrier at all) but the children become accustomed to use the paths separated from the auto roads, and do so; and parents are more likely to stay in a town where their youngsters are safe."2

Other reasons for the walkway system were many: to create a more pleasant experience for walkers, to reduce the difficulties of clearing snow off of sidewalks, and to prevent water from splashing onto sidewalks from passing cars and freezing overnight to create dangerously slippery surfaces. The city's planners' "Master Plan" also included the later installations of designated cycling paths, though these were never built.

Construction on the walkways began in the summer of 1955, a year after the first residents of Nechako had first moved in, and by 1957, 32,829 linear feet of walkway had been installed. Early surveys showed that Kitimat residents had taken to their new transportation system; in 1957, only 58% of surveyed residents owned cars, and walking was the main form of transportation for 60% of residents.3

Yet that wasn't quite good enough for members of the Town Planning Department, and in a 1957 report on the walkway systems, they recommended that the Municipal Code be revised to include a bylaw requiring pedestrians to use these walkways where they were available.

"The pedestrian must be encouraged when possible or made when necessary to use available walks, not only for his own protection but for the protection of the driver."4

Today, the walkways are a point of pride for many Kitimat residents. They are still maintained to this day, though no bylaw requiring people to use them is currently on the books. Likely, it wasn't necessary.

The other main aspect of planner Clarence Stein’s greenspace model hasn't stood the test of time quite as well as its walkways. When Kitimat's houses were first constructed, house orientation had the living room and front door facing greenspace, and the kitchen facing the roadway. In effect, the houses were turned around. The idea behind this orientation was to encourage walking via greenspace to the neighbourhood centre rather than travelling by automobile. One could step out of their front door and into a community greenspace. From there, one could get to school or to a friend's house without once stepping onto a road. Much of the initial housing was oriented this way, but later house construction saw a return to the traditional orientation. Stein made efforts to educate the residents of Kitimat, explaining to them the ideals behind the new, unique house orientation.5 Evidently, it did not work.

Despite bumps in the road and changes throughout time, the greenspace model still defines Kitimat's layout and design. The walkways are still in use, and the many parks and public spaces make the town a walkable, pedestrian-friendly community.

6. Family in Kitimat

1964

This photograph shows the Nechako Centre in its prime, when every building was occupied by a bright new store and the lawns and gardens were neatly manicured. On the pathway towards the Centre, two women stand talking with a kid in a stroller between them. The arrival of women and children in Kitimat signalled the end of the construction period and the beginning of a true, balanced community. Women helped shape almost every aspect of life in Kitimat.

While the population of Kitimat was originally largely male, with only a few women on site, these demographics shifted rapidly once Kitimat's townsite began to be laid out. Families flooded into Kitimat, and there was a massive baby boom that filled the town with young children. Life wasn't always easy in the new community, and the remoteness of the town made building a home here an adventure, but the women who arrived embraced everything Kitimat had to offer and helped create the town's unique identity.

* * *

Alcan, however, thought a town full of single men would be lonely and disruptive. The sociologist hired by the company to help plan the town pointed out, "Loneliness of adults might well reproduce symptoms from North American pioneer life of the nineteenth century: aggressive roughhousing, brawling, disorganized sex behaviour, especially if the settlement was made quickly by lonely and unmarried men."3

Alcan promoted Kitimat as a family friendly community. Families began to populate the town. Men who wanted to work at the smelter and live in Kitimat permanently sent for their families or were hired and brought their families with them. Kitimat was planned from the beginning to be a model family town.4

Alcan's push to attract families paid off. The first settler woman arrived in the town of Kitimat in 1952, and the first settler baby was born in the town that same year, luckily just after the construction of the hospital. And once houses began to be built in the Nechako neighbourhood in 1954, families flooded in. Men who had left their wives and children behind in the city while they worked for Alcan were able to bring their families to the community at last. Soon, there was a baby boom, and school officials struggled to expand temporary classrooms to deal with the arrival of hundreds of new students. In 1956, Kitimat's hospital recorded an average of 40 births a month.4 By 1958, there were 3,500 children in Kitimat despite the population being only 9,000. Around 300 babies were born every year.6

The first school in the area began at Smeltersite, at the head of Douglas Channel, in 1952 with 26 students. In the official town of Kitimat, located upriver from the Smeltersite, the first school was the Nechako Elementary, built in 1955 with nine classrooms—a very large jump from the 26 children who lived at Smeltersite just three years previously. In the following years, other schools opened in other neighbourhoods to accommodate the population spike.

Many aspects of domestic life in early Kitimat were challenging. The main challenge, of course, was the town's remoteness. Everything that arrived in the town had to come by boat, and the initial process of moving in was hectic and messy. The furniture of dozens of families was delivered on pallet boards to the wharf on Douglas Channel and covered in tarps. A foreman at Alcan remembers that it was "a horrible mess—we couldn't find our fridge for a week."7 Electricity was often unreliable and the townsite was muddy.

There were few stores in those earliest days. But remoteness was short lived. In 1957, City Centre commercial properties opened. The Terrace-Kitimat rail line and the Terrace-Kitimat Highway opened respectively in 1955 and 1957, connecting Kitimat with the rest of North America.

There was a feeling of community and safety, along with "a feeling of belonging to a great adventure out of which grew a strong community spirit."8 Children were able to run wild in relative safety. Community groups formed and teas and coffee parties were held. Neighbours had to help each other—there was no other way to get by. It wasn't a perfect set-up, but it was one which, years later, many of the original settlers could look back on with fondness.9 And despite all of the planning, despite the academic thought and deep philosophy that went into building the town, it was the people who truly created Kitimat:

"I think Kitimat people made it happen. You know I think the fact that the plan didn't develop the way that they wanted to, didn't deter the people from saying 'well it's not going to stop us from doing what we want to do'".10

Endnotes

1. Company Town to Community

1. Beck, Janice. Three Towns: A History of Kitimat. Kitimat Centennial Museum Association, 1983. 49.

2. Bodsworth, Fred. "How to Start A City from Scratch." Macleans, May 1954. URL: https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1954/5/1/how-to-start-a-city-from-scratch.

3. Kendrick, John. People of the Snow: The Story of Kitimat. NC Press Limited, Toronto, 1987. 140.

4. Barman, Jean. The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007. 189-215.

5. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project." Royal BC Museum. https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/northwest/kitimat/memories.html.

6. Boyer, David S. "Kitimat—Canada's Aluminum Titan." National Geographic, Volume CX, Number Three, September 1956. 387.

7. Bodsworth, Fred.

2. Kitimat's Town Planners

1. "Kitimat: A New City." Special Reprint from the Architectural Forum, 1954.

2. Kendrick, John. 136.

3. Bodsworth, Fred.

4. Bodsworth, Fred.

5. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

6. Kendrick, John. 169-174.

7. Kendrick, John. 174.

3. Kitimat's Neighbourhoods

1. "Alcan Project History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/alcanproject.

2. Beck, Janice. 59.

3. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

4. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

5. Bodsworth, Fred.

6. "Kitimat: A New City."

4. A Multicultural Kitimat

1. Kendrick, John. 143

2. Kendrick, John. 142.

3. "Alcan Project History."

4. "Alcan Project History."

5. Kendrick, John. 143.

6. Kendrick, John. 144.

7. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

5. Kitimat's Famous Walkways

1. "A Walkway Programme for 1958". The Corporation of the District of Kitimat, Town Planning Department. December, 1957. 3

2. "A Walkway Programme for 1958." 4.

3. "A Walkway Programme for 1958." Appendix D.

4. "A Walkway Programme for 1958." 14

5. Cross, Brad. 12.

6. Family in Kitimat

1. Beck, Janice. 55.

2. "Settling In: Highlighting 50 Years of Kitimat's History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/settlingin.

3. "Kitimat: A New City."

4. Bodsworth, Fred.

5. Boyer, David S. 384.

6. Beck, Janice. 64.

7. Beck, Janice. 60.

8. Beck, Janice. 60.

9. Beck, Janice. 60.

10. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

Bibliography

"A Walkway Programme for 1958." The Corporation of the District of Kitimat, Town Planning Department. December, 1957.

"Alcan Project History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/alcanproject.

Barman, Jean. The West Beyond the West: A History of British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007.

Beck, Janice. Three Towns: A History of Kitimat. Kitimat Centennial Museum Association, 1983.

Bodsworth, Fred. "How to Start A City from Scratch." Macleans, May 1954. URL: https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1954/5/1/how-to-start-a-city-from-scratch.

Boyer, David S. "Kitimat—Canada's Aluminum Titan." National Geographic, Volume CX, Number Three, September 1956.

Cross, Brad. "Modern Living "hewn out of the unknown wilderness": Aluminum, City Planning, and Alcan's British Columbian Industrial Town of Kitimat in the 1950s." Urban History Review, Vol 45, Issue 1, Fall 2016. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042292ar.

Kendrick, John. People of the Snow: The Story of Kitimat. NC Press Limited, Toronto, 1987.

"Kitimat: A New City." Special Reprint from the Architectural Forum, 1954.

"Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project." Royal BC Museum. https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/northwest/kitimat/memories.html.

"Settling In: Highlighting 50 Years of Kitimat's History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/settlingin.