Driving Tour

Kitimat's Aluminum Smelter

The Arrival of Industry in Kitimat

By Natalie Dunsmuir

This tour is a long distance to walk and a car or a bike is highly recommended.

The town of Kitimat is fairly young on the timeline of Canada and came into being in the 1950s as a settler community based on the establishment of a huge aluminum smelter and associated hydroelectric project. Industry has shaped and founded the community. The Alcan Aluminum project was the largest industrial construction project in the world at the time, and the remote wilderness of the region only added to the complexity and difficulty of the task. Six thousand workers toiled here for nearly five years, living deep in the wilderness in camps only accessible by boats, planes, and helicopters.

They worked to transform the landscape. They built a dam which flooded 92,000 hectares of land. They hollowed out a mountain to build a power station. They dredged the Douglas Channel to create a deep-sea port. All of this was done to create a new resource that was beginning to shape the modern world: aluminum.

Yet before all of this was here, before the hum of the smelter came to dominate the channel and the town of Kitimat sprung up among the mountains, this land was the home to the Haisla First Nation. For thousands of years, the Haisla have lived in this region. The town of Kitimat is built on unceded traditional territory.

On this short driving tour of Kitimat, we will witness the juxtaposition which shapes Kitimat, exploring how deep wilderness intersects with industry. Our first stop will be at Coghlin Park, which provides expansive views across the town and towards the ocean and distant smelter. Here, we will learn about Kitimat's early history, before the Alcan Aluminum project had begun to take shape. Next, we will drive past the City Centre and to the Giant Spruce Park. A short walk leads to the waterfront, where you can see across the Kitimat River to Alcan's so-called "Million Dollar Baby": the sandhill. Here, we will look at how and why Kitimat came to be chosen as the site of the Alcan aluminum smelter, and what it takes to produce aluminum.

Stop three, located down Haisla Boulevard and Alcan Road next to the smelter itself, digs into the immensity of the project and looks at what it took to construct. Stop four explores the steps of the old Hudson's Bay Trading Company which once provided for smelter workers. Here, we will dive into what life was like for the construction workers during Alcan's early years.

Our final stop takes us to Hospital Beach, where Kitimat's first temporary hospital was once located. Enjoy the beautiful views of the Channel and learn about the construction and official opening of the smelter and what came next for the young town of Kitimat and its economy.

This project was created in partnership with the Kitimat Museum and Archives.

1. In The Beginning

1964

The town of Kitimat has long been defined by its identity as "the Aluminum City of Canada." In the picture above, three workmen begin painting a sign with a map of the early town of Kitimat. One stands on a ladder while the other holds it in place and the third looks on. The mountains and trees in the background contrast vividly with the cleared space and power lines around the sign. Industry has come to Kitimat and transformed the landscape.

* * *

The Haisla lived sustainably during this time, harvesting many foods from the ocean and surrounding valleys or wawais. Ownership of resources in wawais are by clan. Traditional foods continue to be harvested and eaten today, when available.

Europeans first came to the area in 1792, when the Spanish frigate the Aranzazu arrived at Kitamaat, captained by Juan Martinez y Zayas. These explorers were looking for the mythical Strait of Fonte, which was said to reach the Atlantic but of course did not exist.2 Their journey was brief—unable to find the mythical passage, they moved on. The next Europeans to arrive were British. Captain George Vancouver explored the region and mapped a portion of it in 1793, renaming with European names the mountains and channels known by the Haisla. Vancouver's crew sailed on the Discovery to the head of the Douglas Channel. This journey was also brief, however.

For nearly a hundred years, no other Europeans travelled to the area. But gradually, in the late 1870s and early 1880s, Christianity arrived in Kitamaat. The missionary Susannah Lawrence arrived in the early 1880s with the goal of establishing a mission house. By 1894, Reverend George Raley was opening the first residential school in Kitamaat.3 This school remained open, in various forms and under various names, until 1941.

The school forced students to speak English and learn Christianity. Outbreaks of disease occurred frequently, and a bad string of outbreaks in the early 1920s had a mortality rate of 50%. In response, parents took their children out of the school and refused to put them back in. It was not until a public meeting with the Indian Agent, RCMP, and local missionaries that "a mix of threats and promises from the RCMP constable and the Indian Agent"4 had parents return their children to school. The residential school eventually closed in 1941 and was replaced instead by a day school.

Missionaries were not the only settlers to come to the region during this time. A frenzied moment of excitement in the early 1900s brought settlers to the area when it was briefly believed that Kitamaat would be chosen as the terminus for the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. Charles Clifford, a Hudson’s Bay Company manager and member of the BC legislature for the Skeena riding, came to the area as a land speculator. He opened a hotel and wharf in 1904 and planned the layout of the new town of Kitimaat (a new spelling) with 14 streets and seven avenues, across the water from Kitamaat. Mail service and a registered post office were established in Kitamaat.

But the excitement was not to last. In 1907, the terminus for the railway was chosen, and it was not Kitamaat. Instead, Kaien Island, now home to the town of Prince Rupert, received the honour. The excited speculators for the new town of Kitimaat had defeated themselves. The rumours of railway glory had driven up land prices in the area to such an extent that the railway directors decided to build somewhere cheaper. By 1920, non-indigenous presence and interest in the area had been reduced to a logging camp and four settler families. By 1945, all had left.5

The area was again empty of European presence. But this emptiness was only for a short time. The stage was set for something big. The area was given a short rest before something new arrived: the Alcan project and everything that came with it.

2. The Coming of Alcan

1952

The town of Kitimat exists, like many Canadian towns, due to the availability of important resources. For Kitimat, these resources are hydro-electric power, a transportation corridor through the mountains to tide water, and the sea access of the Douglas Channel. To utilize the water of the Nechako River, an immense revision of geography was needed. The Kenney Dam opened in 1952, the reservoir filling and flooding the land in Tweedsmuir Park. Beginning in 1951, a 10-mile tunnel was cut through the Coastal Mountain range, and the water once bound for the Fraser River from the Nechako River was diverted through the tunnel at the reservoir’s western end at West Tahtsa Lake intake.

Today, the water thunders through the tunnel, falling 790 metres into the powerhouse turbines, eight of them placed in a cavern a kilometre inside Mount DuBose. The tailrace tunnel pours the water out onto Canada’s west coast. The power created is taken over the mountains on an 18-kilometre transmission line to Kitimat where aluminum is produced at the smelter which opened in 1954. The massive Kitimat Project was completed in just five years—dam, tunnel, powerhouse, Kemano, transmission line, smelter, and Kitimat.

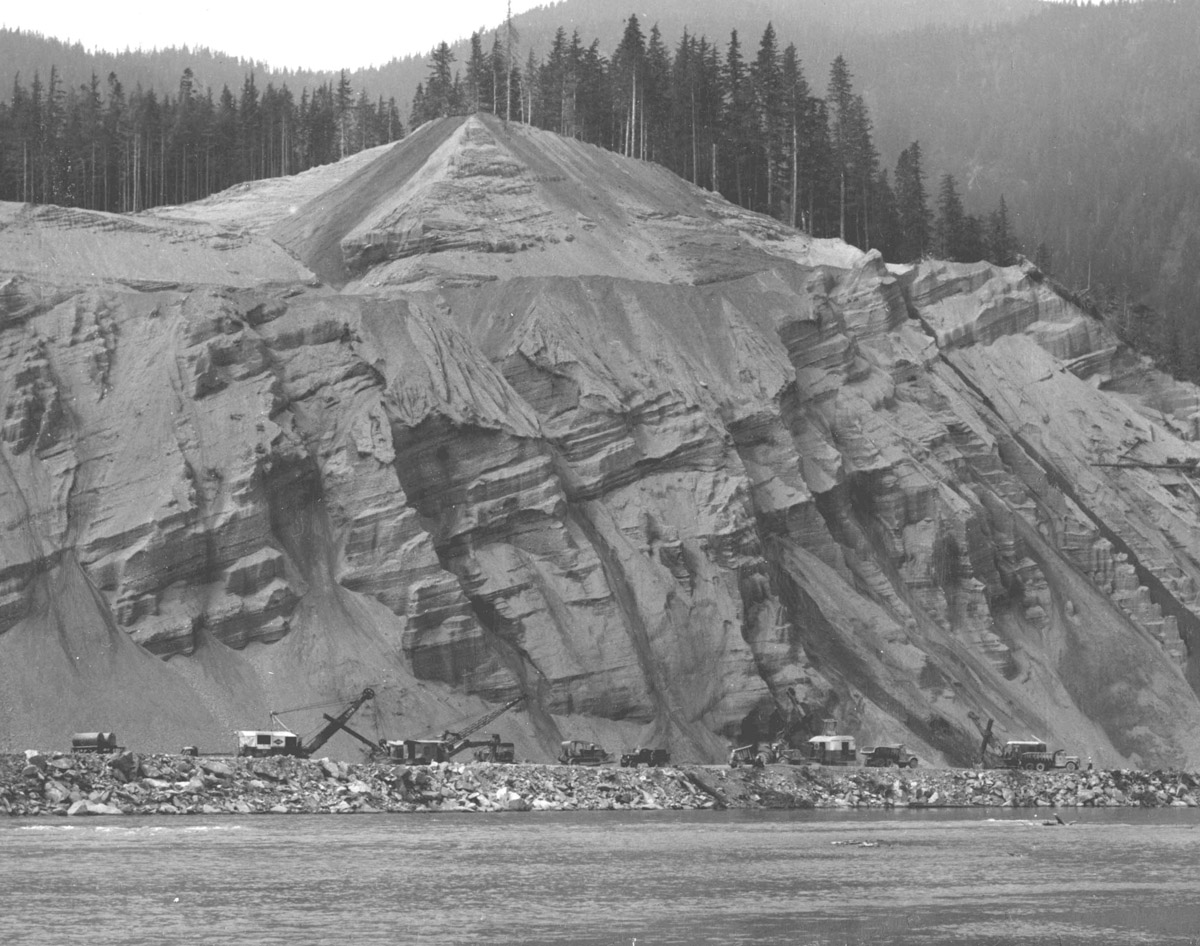

The sandhill, pictured here across the Kitimat River from the townsite, was an unexpected, very welcome bonus to those building the smelter and town. Known to Alcan engineers such as Hugh Meldrum as "Alcan's million dollar baby" 1, the massive deposit of gravel and sand has continued to be used by industry in Kitimat since it was first discovered. In the construction of Alcan, it was used to reinforce the mud flats on which the aluminum smelter at the head of Douglas Channel was built. Originally, it stretched all the way to the banks of the Kitimat River. During the construction of the smelter and town, however, it decreased in size by an average of 14,630 cubic metres a day.2

The Kitimat Power Project generates cheap electricity, and lots of it. The thing aluminum production requires most of all, almost as much as the bauxite ore from which the metal is made, is electricity. And so, Kitimat was put on the maps of industry professionals across the world.

* * *

New technologies in the twentieth century allowed for the production of electricity from water. This electricity was cheap, clean, and, in Canada, available in incredibly large quantities. It therefore attracted the sort of industries that require these massive amounts of power. The aluminum industry was one of them, spurred on in the 1940s by the Second World War, which required this light metal for aircrafts and other tools. Canada's aluminum production increased during World War II by about 500% as the country turned more and more towards manufacturing and industry.4

Aluminum is very much a global affair. The bauxite ore is mined in tropical and semi-tropical regions far from Canada, such as Australia, South America, Africa, and the Caribbean. But these regions generally lack the amount of electricity needed to process this ore, and so the mineral is sent on a journey north. Aluminum does not appear in nature. Or at least, it does not appear in nature in its pure form. Unlike gold or other metals, it must be chemically refined. Bauxite ore is made up of three primary oxides: silicon, iron, and aluminum. These must be separated, a process which involves a lot of power.

In 1939, Canada's aluminum output was 165.7 million pounds. By 1945, this number had increased to 431.4 million pounds.5 Driving this production was the company Aluminum Limited, a Canadian off-shoot of the Aluminum Company of America. This company built several smelters and hydroelectric plants throughout Quebec, in the Saguenay Valley. Eventually, the company changed its name to the Aluminum Company of Canada, or Alcan for short.

After the Second World War, Alcan set its mind towards expansion. The company began to turn towards British Columbia for their next project, where the untapped hydroelectric potential was astonishing, the government friendly to industry, and the coastline poised to access Japanese markets. Between 1948 and 1951, the company conducted surveying work and examined possible locations for the new project.

In the beginning, Kitimat was not even considered as a potential spot. Powell River, the Bute Inlet, Dean Channel, and Kemano Bay were all options first. Yet gradually, they were eliminated, and a new contender took shape. Both Kemano and the Dean River were discarded due to their inaccessibility. McNeely DuBose, the so-called "commander" of the Kitimat project, did not believe workers would want to remain permanently in a town that had little hope of ever receiving a road or rail link and was only accessible by boat or plane.6

Eventually, Kitimat was chosen as the site. The Douglas Channel would provide access to the wider ocean and the Nechako Reservoir would provide the needed electricity. Additionally, Kitimat was located in a long, relatively flat valley, near the already established town of Terrace, meaning that rail and road connections were not so distant a dream. An agreement was struck between the government of British Columbia and Alcan on December 30th, 1950. It gave the company a lease on the region's land and water for 50 years, along with the ability to flood up to 300 square miles of land in order to tap into the hydroelectric potential of the area. In exchange, Alcan proposed the spending of up to $500 million on the project, which was 2% of Canada's Gross National Product at the time.7

The paperwork was signed and the site chosen. But there was still a long way to go before the smelter could open and aluminum be produced. First, the company would have to create the power project—dam, reservoir, tunnel, powerhouse, and transmission line for the smelter—completely transforming the land in the Northwest, a difficult task by any standard but made more difficult by the remoteness of the region. Then the smelter would need to be constructed and a town would be needed to house the workers. The story of Alcan and Kitimat had only just begun.

3. An Immense Undertaking

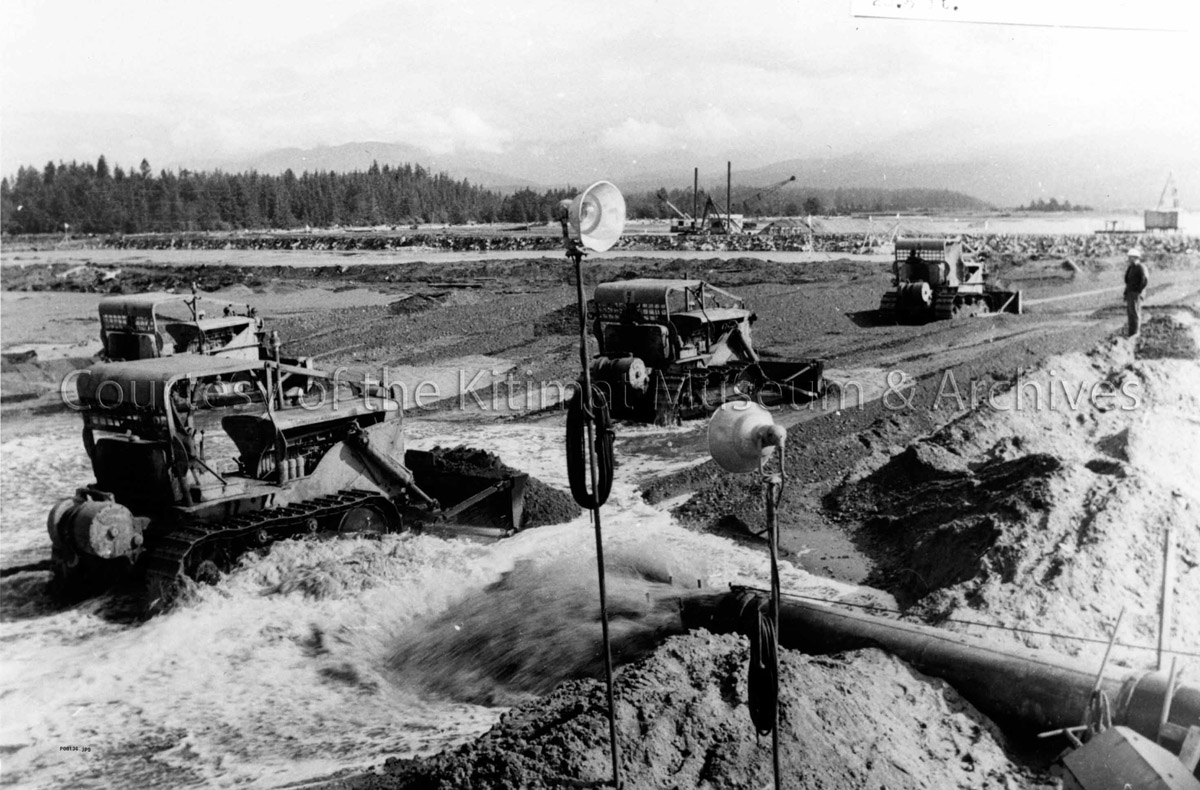

The magnitude of Alcan's Kitimat project was astounding. During its construction, it was the largest industrial construction project in the world, and when it first opened it became the largest aluminum smelter in the world as well.1 If you look to your left, you will see the smelter beside you, covering kilometres of land and operating 24/7. The picture above shows this behemoth of industry's initial construction, as machines work to reinforce and flatten the mudflats on which the smelter is located. Construction on the project lasted nearly five years and involved thousands of workers.

* * *

"I like these Canadians. I admire them for the way they shovel up mountains and throw the map all around the place and dam up rivers to make them run backwards through a mountain--to make aluminum."2

This rather colourful description of Alcan's work was not inaccurate. The project sought to transform the wilderness, harnessing it for the sake of industry. Alcan and its construction workers saw the project as a competition, humans against nature to "tame" the wilderness. They envisioned themselves as pioneers setting out onto a bold new frontier.

A statement released by Alcan described Kitimat as "A frontier that is like no other newly-opened in history… The spur for civilization’s march into this fog-ridden, mountainous wilderness is one of the largest single efforts ever made by man to turn natural water resources into productive power."3

The Alcan construction project involved six unique aspects. The first was the damming of the Nechako River, the second, the creation of a ten-mile long transmission tunnel, and the third, a huge power plant located inside a mountain. The fourth aspect was a transmission line to carry the resulting power 77 kilometres to Kitimat, and the fifth was the smelter. The sixth, of course, was the construction of the town itself.

Construction began in 1951 and lasted until the smelter opened in August of 1954. Over the course of these years, 6,000 workers toiled in the wilderness. The first aspect of the project, the dam, was completed in 1952, and the waters soon began to rise. Upon completion, it was the third-largest rock-filled dam in the world and had a maximum generating capacity of 1,680,000 kilowatts. It flooded 92,000 hectares of land, most of which was located in Tweedsmuir Provincial Park. At the time, environmental activism had yet to emerge as a force with any power, and if anyone protested this massive loss of habitat, their voices gained little attention.

Far more of an issue was those who lived on the land which would soon be underwater. At the time, the land was the home of 79 scattered European farmers and about 200 Cheslatta T'En First Nations living in four villages. The settlers fought Alcan for proper compensation for their land throughout a long process of public meetings and succeeded in securing a settlement: Alcan would buy their land for $15,000 a quarter section, a price which was five times the amount that Alcan had originally offered them.

The Cheslatta T'En First Nations did not get the same deal. The Band was informed that their land would be underwater a week before it was, and though they were asked to vote on a settlement arranged for them by the Indian Affairs Department, only twenty of the thirty-six voting members knew of the meeting—the others were surveying their trap lines. The vote passed, and the Nation received little in the way of compensation. Likely, they felt they had no other alternative.4 The flood, after all, would soon begin. It was not until 1993 that the Cheslatta T'En received proper compensation for the 1,053 hectares of reserve land they were forced to give up. A $7.4 million settlement from the Canadian government was finally given to the Nation that year.5

In the meantime, the Cheslatta were forced to move 30 miles to the north, to Grassy Plains. And while they eventually received small compensation cheques, they were also forced to pay for their new land and farms. They had to travel during a difficult spring thaw, living in cold, inhospitable tents until new land was assigned to them.6

The transmission tunnel, line, and powerhouse were far less controversial, though their construction was certainly not easy. The transmission tunnel is 16 kilometres long and drops in elevation nearly 800 metres. It is wide enough for four cars to drive through side by side. The dangerous work of construction killed sixteen workers.7

The powerhouse, located inside a mountain, was also a work of engineering genius and became one of the world's largest human-made caves. It is 25 metres wide, 41 metres high, and nearly 215 metres long, containing eight turbine generators.

The transmission line running from this powerhouse to Kitimat did cause some problems. McNeely DuBose, the vice-president of the Kitimat project, did not want to build the line on the coastline, as it would be a long, indirect journey to take. The alternative, however, was to cut through the mountains, where ice and snow would be major threats to the lines. And, not wanting to incur the cost of building the towers along a tall ridge, the lines were put through a hanging valley.

They did not last long. In the winter of 1955, an avalanche destroyed three of the towers, cutting off power to the town and smelter. It took nine days to restore the power, during which time Kitimat lived off of the temporary diesel sets that had been used during initial construction. The avalanche problem in that valley was solved by stringing cables from one end of the valley to the other at a height of 150 metres at their lowest point.8 All of this work took place over the course of just a few years. It took massive amounts of energy, innovation, and physical labour. And while the dam, tunnel, powerhouse, and transmission lines were being constructed, work was also beginning on the smelter and townsite.

4. Life During Construction

The men in this photograph are standing on the steps of Kitimat's first Hudson's Bay Company store. The store was located in Smeltersite, a worker camp that operated before the townsite of Kitimat was officially laid out. This building was not only the community's first department store and home to the post office, but a place for single smelter workers to gather and eat together.

Life for Alcan's employees in the early years was full of challenges, from Kitimat's remoteness to the physical, sometimes dangerous nature of the job, to the loneliness of living in small wilderness work camps. But there were benefits too, including the feeling of being part of something big, a project which was changing the very landscape of the area. Work on construction of the Alcan project was at least never dull.

* * *

Whatever job an employee worked was bound to come with its own unique set of challenges. No work was easy, whether you were constructing the dam, carving out the tunnel, or just painting signs to mark the work sites. A certificate was given to employees of the project by Alcan and catalogues some of the challenges they faced:

"From the tortures of the elements, barrack blues, camp and maintenance maladies, tundra trembles, glacier giddiness, transportation tempest, jeep jitters, highline heaves, helicopter hops, equipment evils, penstock pitches, tunnel-torments, powerhouse punches, transmission-line laments, design deliriums, construction cussedness, and all devious delusions of grandeur acquired while in front of a snowball—too far from a highball or behind the 8-ball—in this wilderness where travail has been great and in which has now been caused to be damned and dented and ornamented and heralded to the four winds: The Alcan Project."3

Some camps gained reputations for being more modern equivalents of gold rush communities—crazy frontier towns full of gambling and alcohol. And there was some truth to this. Isolated from the outside world with little to do after work except eat, many workers turned to gambling for some evening amusement.

"Gambling and boozing certainly took place at Kenney Dam. We had our own gambling tent. It was mostly blackjack and dice. Some players were professionals. They would hire on as bull-cooks or labourers just to get a chance to gamble. There was a lot of money made and there was probably a lot more lost. I remember the Melange Brothers, French-Canadian chaps who won a Ford - a brand-new Ford one night, but they never did see it because they lost it again that night."4

There were also plenty of more innocent forms of entertainment in the early work camps, however. Most camps eventually got their own recreation halls, which would host movie nights, talent shows, art exhibits, amateur theatre performances, and concerts. These halls were crucial gathering spaces for the men after long days at work. Social clubs were even formed, and photography was an extremely popular hobby among workers who were no doubt inspired by the wilderness they were immersed in. The work camp at Anderson Creek even got a twelve-lane bowling alley.

In most early camps, the men lived either in rough, quickly built bunkhouses, tents, or trailers. But near the Smeltersite at the head of Douglas Channel a different solution to the problem of accommodation was found: The Delta King.

The Delta King was a steamship from California, launched in 1925 to travel the rivers between San Francisco and Sacramento. The boat ran between these two cities for fifteen years, but was eventually retired in 1940 as the popularity of river travel declined with the rise of the automobile. It then worked as a Navy ferry until 1946, when it was again retired. Alcan bought the vessel in the 1950s to act as worker accommodation in Kitimat. The engine and sternwheel were removed and put in storage, and the boat was towed by tugboat to Kitimat, arriving at the head of the Douglas Channel on May 8th, 1952. She was then beached on shore, where she acted as living quarters for some 200 men.5

The early Kitimat work camps were made up almost entirely of men. The women who did arrive in Kitimat in the early years, starting around 1952, worked office jobs or in the hospital. These women had to face being outnumbered a hundred to one by lonely men who had been living in the wilderness for far too long. In 1954 at the townsite camp, for instance, there were only three women.6 Unsurprisingly, they received many marriage proposals.

As the project began to move towards completion, a more balanced community gradually formed. The townsite of Kitimat began to take shape, and workers moved their families into permanent accommodation. And when the smelter opened with a permanent workforce and the work camps closed, Kitimat became an established, independent town.

5. The Smelter Opens

The construction of the smelter itself was a massive job, not least due to where it was located. As you can see from this aerial photograph, taken sometime after construction, the smelter occupies a massive amount of land at the head of Douglas Channel. The whole space had to be flattened and reinforced so that the heavy buildings of the smelter would not sink into the mudflats. The channel itself had to be dredged so that the big, deep-sea boats which would bring in fresh shipments of ore and take away smelted aluminum would be able to dock at the smelter wharf.

Construction was finished in 1954, and the smelter opened for business. Life in Kitimat became more stable, with a permanent workforce operating the smelter and the community taking shape. The economy of the town eventually diversified, with more forms of industry setting up shop in the community.

* * *

The mudflats at the end of the channel were made up of deep layers of loose silt, often as much as a hundred metres deep. This, of course, was not a stable foundation for a large industrial project to sit upon. Alcan, therefore, layered gravel from the sandhill onto the mud, often as much as eight metres deep. The weight of the gravel squeezed water from the silt and the entire surface gradually settled to become something more stable. The only unforeseen consequence of this method is that the sediment settled more than the company expected, sinking over a metre throughout the process. Many of the concrete columns that held up the first smelter buildings had to have extensions added to them.1

The other major part of building the smelter, besides the actual construction of the building, was the dredging of the port and construction of the wharf. While the Douglas Channel did provide access to the open ocean of the Pacific, it wasn't perfect; it simply wasn't deep enough for the types of freighters that would be needed. Alcan therefore was forced to dredge the harbour, digging three million cubic yards of material from the seafloor.

Work on the smelter itself took place around the clock, 24 hours a day. It was the only way the company could complete such a massive undertaking in so short a time. Night workers toiled using only the lights provided by their equipment. Between the beginning of construction in 1951 and 1958, when the last buildings were finally finished off and the smelter could begin work at its full capacity, 28,000 tons of steel was erected on the mudflats.2

The first part of the smelter was completed and opened on August 3rd of 1954. In a mark that highlighted Alcan's presence on the world stage, the plant was officially opened by Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, who stamped the first ingot of aluminum. After years of hard work on the construction, Alcan was open for business. Kitimat wasn't to remain a one-company town, however. Alcan knew that would not be sustainable. The company wanted Kitimat to diversify economically. It therefore encouraged other industries to join it in Kitimat. The first one, a sawmill and pulp and paper mill, began construction in 1968. Owned by Eurocan, the mill went into operation in 1970 and remained a major employer for 500 people in the community until 2010 when it closed.3 A methanol and ammonia plant was later constructed in the 1980s by Calgary-based company Ocelot, and was later sold to the company Methanex. This plant was located farther up the Kitimat River, inland from the smelter. It reduced operations and staff in 2005. A liquefied natural gas company, LNG Canada, purchased the Methanex site, and Kitimat LNG purchased the Eurocan site. The Haisla Nation and Pembina Pipeline Corporation plans to develop an LNG floating facility on Douglas Channel, Cedar LNG. Project completion is planned for 2027. Today, these industrial ventures must consider complex issues including climate change, global fossil fuel use, and the impacts of construction and operations on habitat. Unlike when the power project was first constructed in the 1950s, environmental considerations are now a priority. Overcoming and taming the wilderness are no longer options. Kitimat's aluminum smelter is in operation today and recently modernized, though a planned expansion has not happened. Falling aluminum prices and environmental concerns have prevented the use of the second transmission tunnel to increase power and aluminum production. But while these expansions did not take place and Kitimat never became the city of 50,000 first envisioned by its creators, the town remains a thriving community located amid breathtaking mountain scenery.

Endnotes

1. In The Beginning

1. "Understanding Nuyem." Kitimat Museum Exhibit. “Haisla! We Are Our History,” Kitamaat Village Council, 2005.

2. Kendrick, John. People of the Snow: The Story of Kitimat. Toronto: NC Press Limited, 1987. 10.

3. Beck, Janice. Three Towns: A History of Kitimat. Kitimat: Kitimat Centennial Museum Association, 1983. 15.

4. "Kitamaat: Elizabeth Long Memorial Home." The Children Remembered. https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-histories/kitamaat/.

5. Beck, Janice. 38.

2. The Coming of Alcan

1. Beck, Janice. 47.

2. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project." Royal BC Museum. https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/northwest/kitimat/memories.html.

3. Cross, Brad. "Modern Living "hewn out of the unknown wilderness": Aluminum, City Planning, and Alcan's British Columbian Industrial Town of Kitimat in the 1950s." Urban History Review, Vol 45, Issue 1, Fall 2016. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042292ar. 7.

4. Easterbrook, W.T. and Hugh Aitken. Canadian Economic History. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1967. 520.

5. Easterbrook, W.T. and Hugh Aitken. 547.

6. Kendrick, John. 32.

7. "Alcan Project History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/alcanproject.

3. An Immense Undertaking

1. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

2. Boyer, David S. "Kitimat—Canada's Aluminum Titan." National Geographic, Volume CX, Number Three, September 1956. 398.

3. Cross, Brad. 9.

4. Kendrick, John. 90.

5. "Alcan Project History."

6. Kitimat Museum Exhibit

7. "Alcan Project History."

8. Kendrick, John. 123.

4. Life During Construction

1. Kendrick, John. 142.

2. Beck, Janice. 53.

3. "Alcan Project History."

4. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

5. "The Delta King." Kitimat Museum Exhibit.

6. Beck, Janice. 55.

5. The Smelter Opens

1. Kendrick, John. 115-116.

2. "Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project."

3. "Alcan Project History."

Bibliography

"Alcan Project History." Kitimat Museum & Archive Collection. http://collections.kitimatmuseum.ca/exhibits/show/alcanproject.

Beck, Janice. Three Towns: A History of Kitimat. Kitimat: Kitimat Centennial Museum Association, 1983.

Boyer, David S. "Kitimat—Canada's Aluminum Titan." National Geographic, Volume CX, Number Three, September 1956.

Cross, Brad. "Modern Living "hewn out of the unknown wilderness": Aluminum, City Planning, and Alcan's British Columbian Industrial Town of Kitimat in the 1950s." Urban History Review, Vol 45, Issue 1, Fall 2016. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1042292ar.

Easterbrook, W.T. and Hugh Aitken. Canadian Economic History. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1967.

Kendrick, John. People of the Snow: The Story of Kitimat. Toronto: NC Press Limited, 1987.

"Kitamaat: Elizabeth Long Memorial Home." The Children Remembered. https://thechildrenremembered.ca/school-histories/kitamaat/.

"Living Landscapes: Memories of the Project." Royal BC Museum. https://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/northwest/kitimat/memories.html.

"Understanding Nuyem." Kitimat Museum Exhibit. 2021.