Walking Tour

Moving Mountains

Conflict & Construction at Edgewood

Alexa Dagan

Armstrong Spallumcheen Museum and Arts Society 00199

Nestled just above the shores of Lower Arrow Lake is the rural community of Edgewood, British Columbia. The most direct route to Edgewood Highway 6, which winds through the mountains from Vernon to Edgewood and takes a little under two hours to drive.

It may come as a surprise to learn that this scenic highway was built by men interned by the Canadian government during the First World War. The men mostly came from various parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and were forced to labour under armed guard not for any crime they'd committed, but only because of the nation of their birth. While they worked they lived at an internment camp that was once located where Edgewood's baseball diamond is today. They were surrounded by barbed wire, abused and neglected by their captors, and threatened with a bullet in the back if they tried to escape.

This tour will cover the former Edgewood internment camp and explores the experiences of both those who suffered the hardship in the camp, and of the many who avoided internment only to face a grim reality outside the confines of the fence.

Route

The tour begins at the tri-lingual plaque at the entrance to the ball diamond just off of Killarney Crescent. To reach the ball diamond, take the small dirt road leading east off of Killarney Crescent about 30 meters south of where Killarney intersects with Granby Drive. From the plaque, the next six stops are contained in the baseball diamond. To reach Stop 8, return to Killarney Crescent and walk or drive north until you hit Cemetery Road. Take the next right onto Edgewood Road, where you will find the last four stops of the tour.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Breaking Rocks

Before you begin your tour, take a moment to read the plaque at the entrance to the baseball diamond. The plaque displays the same message recognizing the victims of Canada's World War I internment operations in three languages: English, French, and Ukrainian. During and after World War I, Ukrainian language newspapers and publications were suppressed or outright banned. Memorializing the victims in their own language is a small, but important step in recognizing the injustices the internees suffered.

* * *

They were officially paid 55 cents a day, already a fraction of what they would have made doing the same work as free men. However, half of their wages were held by the government in trust until the end of the war. Of the remaining half, the internees received 12 cents. The rest paid for their rudimentary lodgings (which they were forced to build) and their inadequate rations.

There were about 80 men interned at Edgewood, many of whom had been miners in the Crowsnest Pass area. In British Columbia, the majority of internees were confined either because they were unemployed or were working in industries troubled by labour disputes. The coal mines in particular were a major source of workers for the internment camps.

In 1915 many Anglo-Canadian miners began refusing to work alongside so-called 'enemy aliens'. To appease the miners and therefore avoid any interruption to wartime coal production, the government arrested and interned these miners. The vast majority of the men persecuted under this policy came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most were Ukrainian, but there were also Serbs, Croats, Hungarians, Germans, Slovenes, Poles, Italians, Bulgarians, Turks, Czechs, Slovaks, Romanians, and Italians.

2. Coming to Canada

1915-1916

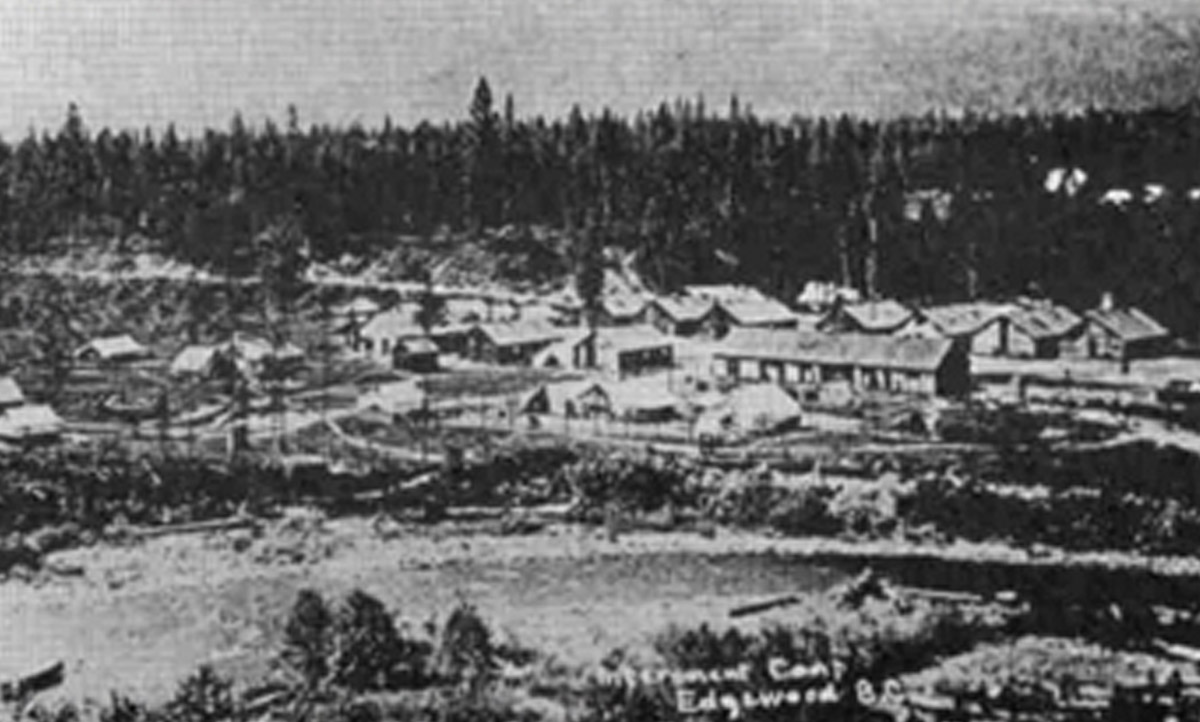

This photo shows a view of the bunkhouses used as living quarters at the Edgewood camp. By this point, some camp buildings have been updated with proper roofs in place of tarps, an important improvement considering the harsh Kootenay winters. Internees are visible in the photo, going about their day as a light dusting of snow covers the ground.

The prisoners were expected to work in all conditions. Refusing work, even due to illness, could result in harsh punishment such as beatings, solitary confinement, and withholding of food.

* * *

Despite these attitudes, potential immigrants from these nations were actively recruited by the Canadian government. In the late 1800s, Canada acquired the massive stretch of land in the centre of the country known as the North-West Territory and feared that if they did not swiftly fill it with settlers, it would be annexed by the United States. They needed settlers, but more importantly given the agricultural potential of the prairies, they needed farmers.

Clifford Sifton, Canada's Minister of the Interior from 1896 to 1905, spearheaded a campaign to attract Ukrainian and Eastern European immigrants, many of whom were impoverished farmers. Later, when defending his decision to recruit these immigrants, he responded with a stereotype commonly held at the time, "I think that a stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born to the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children, is good quality."1

Due to this campaign, the first wave of Austro-Hungarian immigrants largely took up homesteads on the prairies and established tight-knit, block settlements together. This first wave took place between 1891 and 1914 and brought almost 170,000 Ukrainians to Canada, most of whom were attracted by the promise of 160 acres of free land available to those who paid the $10.00 registration fee.

There were several problems. First, Sifton and other officials believed that the Ukrainians they were targeting were from the central steppelands region, which was similar in climate and terrain to the Canadian prairies. However the majority came from a region more similar to southern Ontario, and the new arrivals were unprepared both for the harsh climate and the dramatic shift to mechanized farming, which was well underway in Canada.

Additionally, the majority of the new arrivals were peasants from small rural villages, and many were illiterate. Their traditional dress, religious and linguistic differences were viewed by Anglo-Canadian society as strange and unsophisticated. They also resisted immediate assimilation into Anglo-Canadian society, understandably preferring to settle in Ukrainian communities where they could maintain their language, and cultural and religious practices.

Establishing a homestead was no easy feat either. New homesteaders had to manually clear the land, prepare fields for cultivation, and purchase cattle and machinery. Few could afford these start-up costs, leading many men to seek employment in mines or lumber camps to raise the capital they needed. Due to this, by the outbreak of World War I, many Ukrainians found themselves in more urban areas, some employed and many seeking work. Outside of their block settlements, they faced discrimination and prejudice which made it difficult to find employment.

3. Register and Report

1915-1916

This view of the camp shows a mix of wooden structures and tents at the camp. The mountains visible behind the camp give a clue as to the area's geography. The rugged mountain terrain and isolation of Edgewood made the camp difficult to access and supply. It also made it incredibly difficult to escape. In 1916, a trapper found the body of a man in a cabin not far from Edgewood. At the time, newspapers reported that the remains may have belonged to an internee who had escaped from Edgewood the year prior. Successful escapes from internment camps were rare, but even in the case that someone did escape Edgewood, there was little outside the fence except wilderness to flee to.

* * *

Manitoba newspaper The Brandon Sun explained the humiliating procedure for registering and reporting:

When first reporting, each man is given a card which must be signed every month by the chief of police, postmaster, or justice of the peace, at the place where he is staying. Thus a record of the movements of each foreigner is kept. Should a policeman see a foreigner's card that has not been properly signed by an official, the man is liable to be placed under arrest for breaking parole and interned with the other alien enemies [at the Winter Fair Building.] There are a few of the foreigners enrolled in Brandon who have not been reporting and these are being hunted up and placed under arrest.2

All 'enemy aliens' had their movement, freedom of speech, and associations restricted as well. They were not permitted to leave the country, and municipalities were advised to keep lists of any local Austro-Hungarians or Germans and watch them for any suspicious behaviour.

Many employers also took it upon themselves to fire 'enemy aliens' who worked for them, despite not being asked to do so. The mass firings across the country swept up tens of thousands of men and women. Those who suddenly found themselves unemployed and struggling to find more work sometimes attempted to flee to the United States, which had not yet joined the war. This was a risky choice as it broke the prohibition against leaving the country. Any who were caught trying to cross the border were interned.

In one case that was reported, a man who was in dire straits due to the new rules made a desperate move to save himself from starvation by asking to be interned.

The representative of the enemy did not have employment and his appearance bore out his statement that he was suffering from hunger. He applied to [Private] McDonald at the armoury door for a berth at the internment camp, and met the reply that there was nothing doing unless he was guilty of some offence which brought him under the attention of the military authorities.

"I'm a good man,' said the Austrian. "Speak no English but want to go to camp."

"Start something," said Mac. "Otherwise beat it. You're not on the report list and you're behaving yourself."

"What can I do?" said the Austrian, "I must go to the camp or starve."

"Go down there and cuss the guard," said Mac. "He'll fix you up."

"No! No! He'll shoot me," said the applicant for Government favour.

He never came back.3

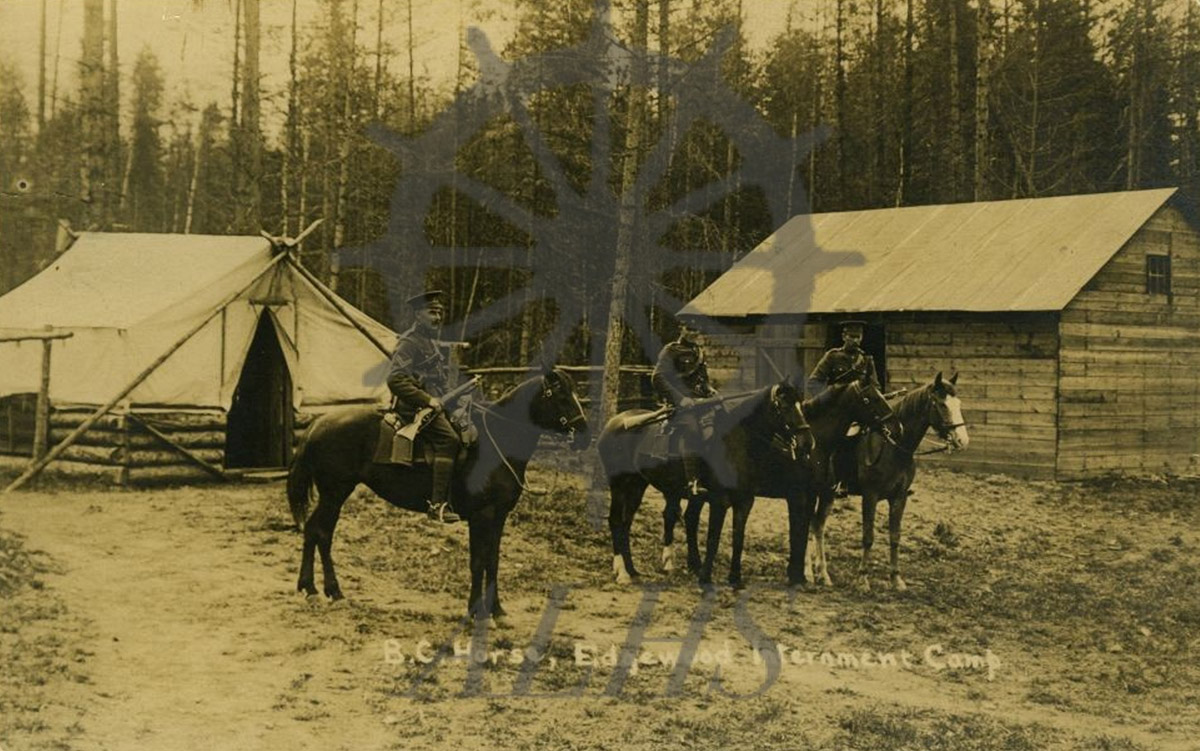

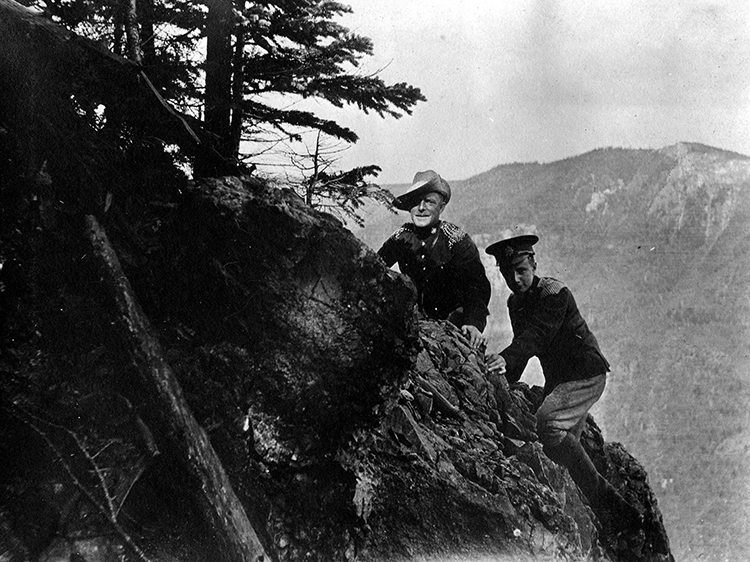

4. Mounted Guards

1915-1916

Three mounted guards stand inside the camp. Behind them is a rough log building with a tarp roof, and another more permanent wooden building. Those who guarded the internment camps were military personnel who were not sent abroad to fight the war in Europe. Many considered the assignment humiliating, including the guards themselves, as well as other military personnel and civilians. Many on guard duty soon began to resent their task and the reputation it gave them, and this translated into apathy, prejudice, and sometimes violence towards their charges. Internees in many camps reported regular abuse from the guards.

Edgewood was among several camps that became notorious for their lack of discipline, control, and organization. Commanding officers at remote labour camps claimed that the remoteness of the camp, difficulty controlling the prisoners and exercising jurisdictional authority, and poor quality of the guards they were sent, all made managing these camps extremely challenging.1

* * *

When men with families were interned, their wives and children were left behind to carry on. Out of the 8,579 people interned during the First World War, 81 of them were women and 156 were children. Only two camps in Canada allowed families to be interned together: Vernon, British Columbia, and Spirit Lake, Quebec.

Interning a family's primary male breadwinner left women and children with few ways to provide for themselves. Some elected to join their husbands in camp to keep the family together, and to avoid the uncertainty and food insecurity they would face in their husbands' absence.

Many Ukrainian women who had had jobs before the war were fired for their nationality, much like the men were. After the war began, many were unemployed, saw their husbands and male relatives shipped off to camp, and struggled to pay rent and feed their children. While some relief was provided to these families, not everyone received it, and many who did found it insufficient. One letter sent by a young girl in Edmonton to her father interned thousands of kilometres away at Spirit Lake is particularly heart-wrenching:

My dear father:

We haven't nothing to eat and they do not want to give us no wood. My mother has to go four times to get something to eat. It is better with you, because we had everything to eat. This shack is no good, my mother is going down town every day and I have to go with her and I don't go to school at winter. It is cold in the shack. We your small children kiss your hands my dear father. Goodby my dear father. Come home right away.

A rather shocking example of government negligence of these 'enemy alien' families appeared in the Globe in 1918:

No Civic Aid for Alien Enemy Baby

Under the order recently passed by the City Council the authorities at the City Hall have decided that an eight-weeks-old baby, born of Austrian parents, is an alien enemy, and it has been denied civic assistance at one of the hospitals.

A city official has undertaken to pay for the infant for two days to see if in the meantime some way out of the difficulty cannot be found.2

Any correspondence between internees and their friends, families, or consular officials outside the camp were subject to heavy censoring. Few letters that detailed the harsh conditions made it intact to their intended recipients. Internees were also cut off from any news regarding the war, and many passed their days in the camps with little idea of what was going on in the rest of the world.

The effects of internment were also not limited to Canada. Any 'enemy alien' caught sending money home to relatives in Europe could be punished. In 1916, the Sault Daily Star reported the outcome of the trial against Helen and Stanley Konopka, who had taken money to Buffalo before sending it on to destitute relatives in Austria. The couple was fined $100 each, or they could choose imprisonment in the Ontario Reformatory for three months.3

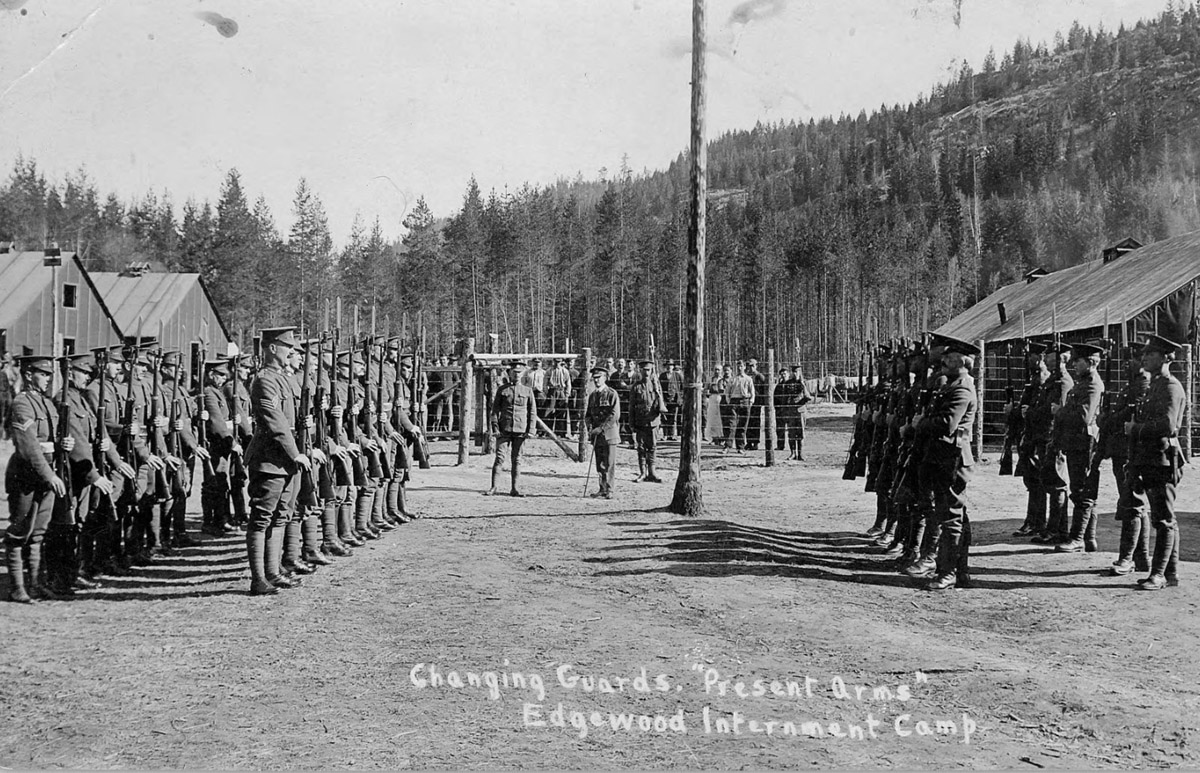

5. The Press

Armstrong Spallumcheen Museum and Arts Society 00199

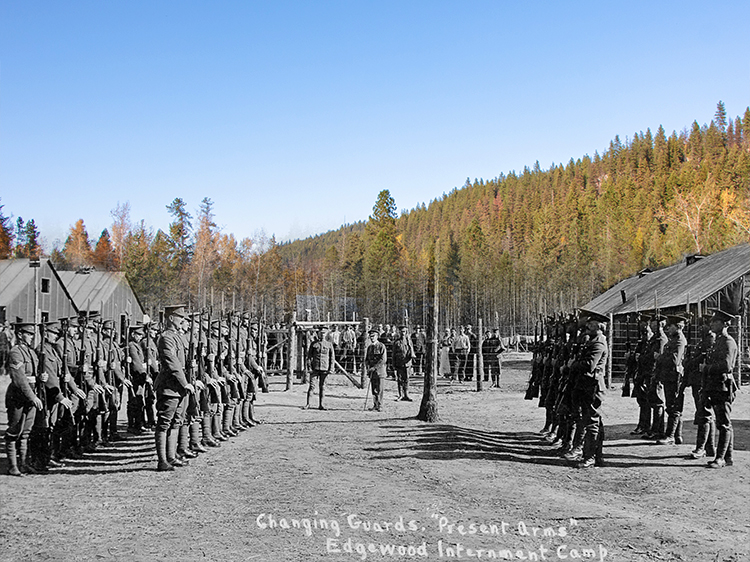

1916

This photo captures Edgewood personnel presenting arms at the changing of the guard just outside the camp fence, while internees observe from within the camp boundary. When it came to outfitting the prisoners for their work, officials did not hesitate in cutting costs. John Black, the road superintendent at Edgewood reported that internees were working in temperatures close to -30 C in the same clothing they wore in the summer.

They wore only a sweater over a light cotton shirt, with no mittens or coat, and additionally, they had not had a change of underwear for six months. Black added that while the internees were prepared to work, it was far too much to expect them to do so while they were so ill equipped.1 In December, it was so cold that the camp lost 11 days of work as the internees were otherwise fully occupied gathering wood for fires to keep from freezing to death.

* * *

An article titled "Alleged German Spies and Supplies Seized" was published in October 1914, reporting on a 90-ton gasoline launch boat bearing a three person crew which was halted near Comox, British Columbia. The article claimed the three occupants carried the last name "Kohse" and that the ship left Victoria carrying a wireless apparatus for communication, nine months worth of supplies, and no clearance papers.2

The article lacked some crucial context: The occupants were in fact Frederick Kohse, his British wife and their 8-month-old son. The boat was obviously not a spy vessel but rather an unregistered fishing boat. They would be interned in Vernon until 1920. Nevertheless, articles like this fueled a climate of paranoia and fear.

When newspapers printed alarmist stories about enemy spies sabotaging railways or planning attacks across the American border, they were almost always revealed to be false. Nevertheless, the press's love for drama and the fear and xenophobia of the general public did a great deal of harm in the early days of the war, when officials were still deciding on the best course for handling Canada's 'enemy aliens.'

Frequent editorials and opinion pieces also reflected the attitudes of many towards the Germans and Austro-Hungarians in their midst. Occasionally an article supported the rights of "enemy aliens," and called on officials to treat them with the dignity and humanity that was afforded to every Canadian. One article published near the end of the war in 1918 captures a sympathetic tone that was rare at the time:

In striking contrast with the convention that Canadians are fighting for freedom, democracy and the observance of national obligations, is the mean and unworthy spirit of persecution displayed towards the so-called "alien enemies" who are quietly attending to their own business here. These people are here on our invitation. For many years successive Governments both Liberal and Conservative, despite the protests of the labour unions, have spent millions of dollars in scattering over Europe invitations to men of all nationalities to settle in Canada, where they would be free from military despotism and be accorded equal opportunities with our own people… Suddenly on the outbreak of the war they found themselves ostracised… Bear in mind that the great majority of these people are only enemies in a technical sense, being about as loyal to Hohenzollern or Hapsburg as a Sinn Feiner is to the British Empire.3 This was a minority view. This opinion piece from 1916 is far more representative of the bulk of articles published:

When peace is declared will the enemy aliens who are now confined to internment camps in Canada be sent to the country of their allegiance as part of the process of exchanging prisoners?

That they will be turned loose into the free life of this country to share in the abounding opportunities it presents is hardly conceivable, says a Toronto paper. Men who were a public danger in time of war ought not to be trusted in time of peace, and ought not to have thrown open to them all the careers and advantages that should be reserved for our own loyal people and brave defenders. Canada has nurtured too many serpents in its bosom…

They cannot be put on the same footing as our own people. They cannot be allowed to snap up the prizes of business and industry before our own men have returned to Canada and been discharged from military service. We must give first thought to our own.5

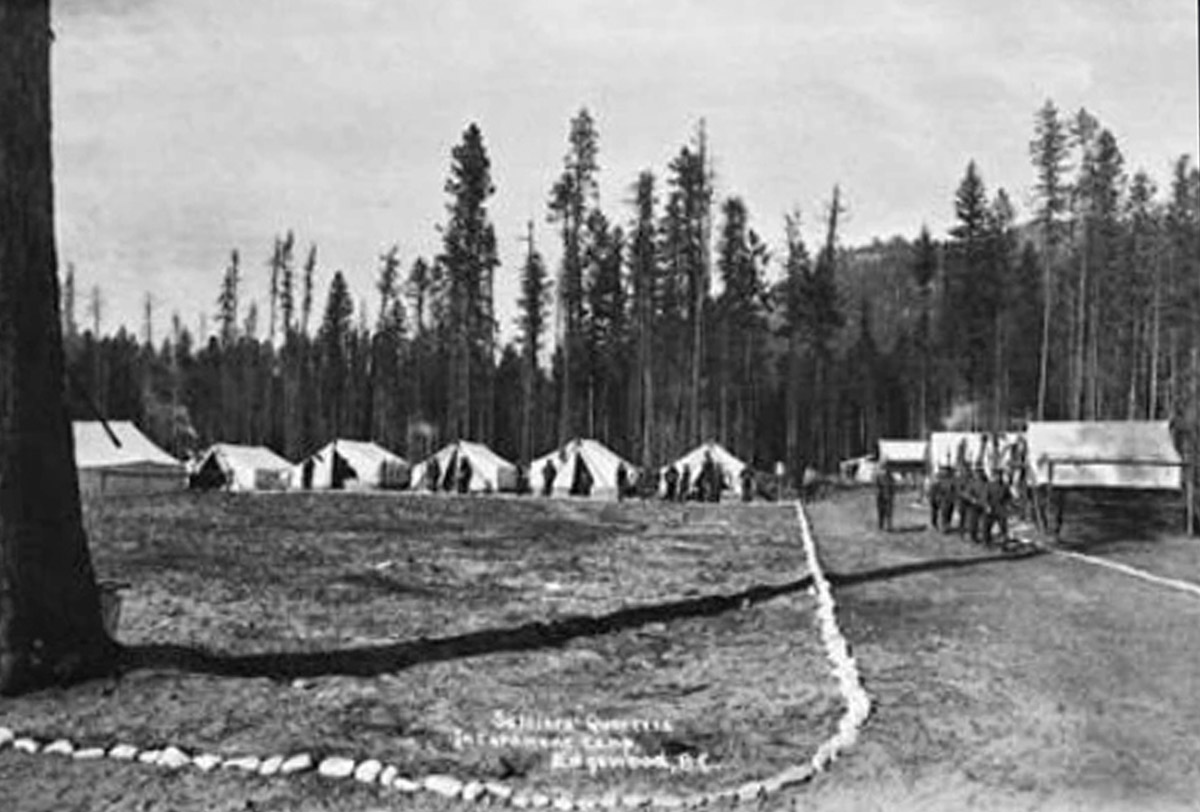

6. The Value of Labour

1915-1916

The caption on this photo appears to read "Soldier's Quarters, Internment Camp, Edgewood BC". A laneway lined with stones curves around a cleared field, and several tents face onto the road. On the right, some guards appear to be marching.

The hard labour of clearing land for the camp and the guard's quarters was done by the internees. In addition to the road and land clearing work, the internees also did most of the labour around camp, including shovelling snow and cutting firewood. In some cases, internees resisted performing labour on behalf of the guards, such as gathering wood to fuel the stoves in their dwellings.

* * *

The road from Monashee to Edgewood, which would connect this district with that settlement on Arrow Lake, has long been asked for, but under existing conditions there is no chance of the Provincial Government undertaking the work in the usual way. The 20 odd miles of road that would have to be built to connect Monashee and Edgewood might, however, [Mr. Ellison] stated, be constructed by this means, as the expense to the province would be very light if the aliens were put to work on the job.1

Labour tensions and prejudice towards the 'enemy aliens' made many in British Columbia angry when Germans and Ukrainians were sent to work in mines and lumber camps. Many British-Canadians felt that jobs in these industries should be reserved for men like themselves who were out of work. However, these same people also resented the idea of internees sitting idle in camp. One Alderman in Nanaimo strongly asserted his views on the matter stating that internees were, "Sitting in the lap of indolence and luxury… when they might be more cheerfully occupied in breaking rocks on roadways or some similar form of light exercise."2

While building roads by hand is no one's idea of light exercise, for the military authorities and provincial government, it looked like an attractive way to make the most out of their newly imprisoned labour force. Road building paid poorly compared to most industries, making it far less desirable. This meant that internees could be forced to build roads without competing with Anglo-Canadian workers for jobs in the mines and in the lumber camps.

On New Year's Eve 1915, one newspaper provided a rough estimate of the value of the labour performed by the internees. By clearing land, building roads, and completing other construction projects, internees proved a labour value of around $1.5 million per year. According to the article, "Although it is costing a good deal to maintain the internment camps, there will be, therefore, a large amount of valuable work accomplished to show for the expenditure which was itself unavoidable."3

However much internment operations may have cost the provincial government and military authorities, it was more than made up for by the pittance paid to the internees and the awful conditions they were forced to work under. Suddenly many long deferred road projects were financially viable.

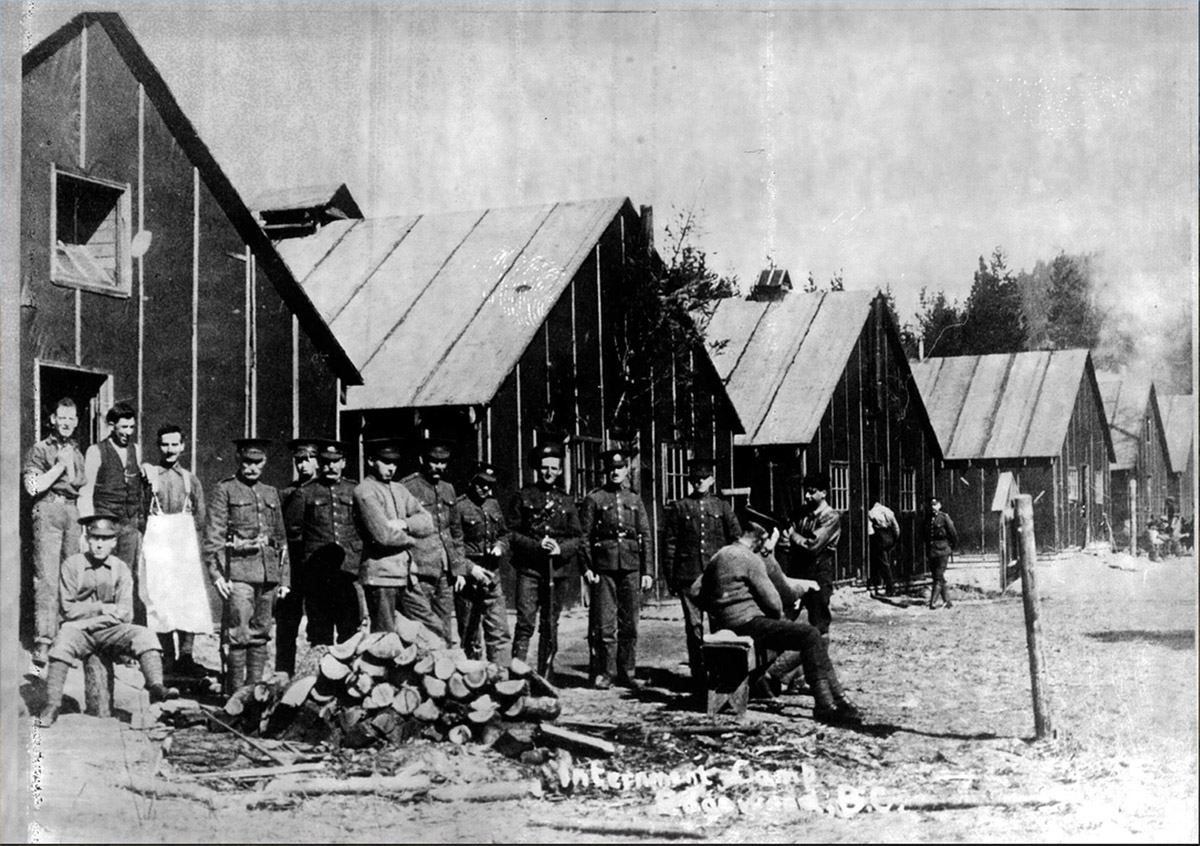

7. Ukrainians Fighting for Canada

Library and Archives Canada 3194048

ca. 1916

A group of men assemble outside a camp building behind a stack of firewood for a photo. The three men on the left appear to be either visitors or camp staff, while the remainder are guards.

In the early years of the war, some detachments were assigned to home front duties such as guarding internment camps, but as the war progressed, many of these battalions were sent to the front lines. Increasingly, candidates for guard duty were pulled from a pool of men ineligible for service, primarily because of their advanced age.

While much of Canadian society questioned the loyalty of their neighbours, many Ukrainian Canadians wished to serve their adopted country and tried to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force to fight for King and Empire.

They had to overcome many obstacles to enlist, since anyone with Austro-Hungarian or German origins was forbidden from enlisting, and any who tried to enlist were suspected of being spies and arrested.

Nevertheless, many Ukrainian Canadians were able to enlist by hiding their origins and enlisting under assumed names. Though the actual number who fought for Canada is difficult to ascertain, one scholar, estimates that as many as 10,000 Ukrainian Canadians volunteered with the Canadian military during World War I.1 However

* * *

Wasyl Perchaliuk had been interned at Castle Mountain, but was one of thousands who were paroled to work for private corporations in 1916. Rather than working for the Canmore Coal Company, he enlisted with the 211th Battalion in Calgary. He never made it overseas. Two days before his battalion was due to depart for Europe, Perchaliuk was detained by the Calgary police and charged as "an alien enemy joining overseas forces."2 He was held while the police tried to determine if he was an escaped internee. On the day his battalion was scheduled to depart, Perchaliuk was still in jail. He committed suicide in his cell.

Nick Chonomod, another Ukrainian Canadian, was interned in a camp near Halifax. He was a naturalized British subject and had been living in Canada for seven years. Additionally, he held a homestead in Alberta, and was married to a woman who had been born in Canada. In August 1914, Chonomod had joined a battalion based in Edmonton, but once his "Austrian" origins were discovered he was arrested and interned. In a letter he sent from the camp to Captain Adams of the 6th Military Division, he repeatedly asserted his loyalty to Canada and Britain, and stated that he could not understand, "on what charge I am being kept here."3

Furthermore, any volunteers with German-sounding names were removed from the ranks and placed under arrest. Many of them had served with the armed forces for years, including with the British forces in South Africa. According to one witness, several of these men "had medals pinned on their breasts by the late Queen Victoria, and one of these wept bitterly when he was taken from the ranks."4

Many Ukrainian Canadians who enlisted with the armed forces during the war did so by changing their names and hiding their origins. Ukrainian immigrants were often registered as Austro-Hungarians by immigration officers, while many were defined by their regional identity, such as Ruthenian or Galicean.

In the case of one man, Filip Konowal, the complicated nature of Eastern Europe nationalities during this period actually worked in his favour. Corporal Konowal is the only Ukrainian Canadian to receive the Victoria Cross, the British Empire's highest award for valour.

Konowal was born in the Ukrainian village Kutkiw, which was in a portion of Ukraine held by Russia, rather than Austro-Hungary. Although Konowal considered himself Ukrainian, immigration officials noted his nationality as "Russian" when he arrived in Canada in 1913. While this was not entirely accurate, the error did save Konowal from being categorized as an 'enemy alien' like so many other Ukrainians. It also allowed him to volunteer in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. He received the Victoria Cross for his bravery at the Battle for Hill 70, where he was credited with single-handedly killing 16 enemy soldiers before receiving a severe gunshot injury to the head.

His Victoria Cross citation shows how he exposed himself to incredible danger over the course of two days:

His section had the difficult task of mopping up cellars, craters and machine-gun emplacements. Under his able direction all resistance was overcome successfully, and heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy. In one cellar he himself bayoneted three enemies and single-handedly attacked seven others in a crater, killing them all.

On reaching the objective, a machine-gun was holding up the right flank, causing many casualties. Cpl. Konowal rushed forward and entered the emplacement, killed the crew, and brought the gun back to our lines.

The next day he again attacked single-handed another machine-gun emplacement, killed three of the crew, and destroyed the gun and emplacement with explosives.

Corporal Filip Konowal is remembered at the Canadian War Museum, by several plaques and memorials in Canadian cities, at his home village in Ukraine, and at a memorial near Loos, France, where the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Hill 70 is commemorated. King George V personally bestowed the Victoria Cross on Konowal with the words, "Your exploit is one of the most daring and heroic in the history of my army. For this, accept my thanks."5

8. Crunching Numbers

1915-1916

This photo shows a full view of the internment camp from across the river. While the labour projects internees worked on outside the camp were physically strenuous, their downtime in the camp had scarcely more to offer. In camp, internees had few outlets for leisure activities. Any hobby or craft supplies had to be purchased from the camp canteen with their limited funds. However, woodworking still became a popular pastime for internees when they weren't working. Internees at camps across Canada made ships in bottles, chess boards, and musical instruments. Walking canes, especially those with a snake motif, were common, and many are associated with the Vernon, Edgewood, and Morrissey camps.

The canes made by internees bear many symbolic images: crossed swords, flags, hearts, crowns, crosses, deer, and oak and holly leaves. Bullet cartridges were often used as tips, which added to the canes' durability. Additionally, crafts such as these could be traded or sold to supplement an internee's meagre income.

* * *

However, an estimated $30,000 in cash was left over in the Receiver-General's Office after the end of internment operations - the equivalent of approximately $439,000 today. Property and other confiscated valuables were also rarely returned. The approximate monetary value of this loss has never been fully calculated.

There were also the economic losses from lost potential. A 1992 report by the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated that between 3,300 and 5,000 Ukrainians lost potential income ranging from $21.6 million to $32.5 million in 1991 dollars, or between $37.4 and $56 million today.3

The report also states that not only internees, but the entire Ukrainian community was affected economically by Canada's actions during the war, "based on wide-ranging discriminatory measures waged against it by the government. For example, the Ukrainian ethnic press was censored, Ukrainians were deprived of naturalization rights [i.e., gaining citizenship rights] for 10 years after the war and the War Time Elections Act prohibited enemy alien immigrants naturalized after 1902 from voting."4

These economic losses were even more devastating considering that many in the Ukrainian community were struggling prior to the war. High unemployment, the difficulty of starting a homestead, and the seasonal nature of much of the work available to immigrants meant that any assets, monies, or valuables confiscated under the internment act was all that many possessed.

9. After the War

1915-1916

This shot looks across the river towards the camp blanketed under a layer of snow. Clearing snow from the camp and cutting firewood to warm the buildings was one of the internees' primary tasks outside of road construction. All of the work performed by the internees, including road work, was performed manually with hand tools such as axes, pickaxes, and shovels. While today we have complicated vehicles such as excavators, backhoes, and graders to handle the majority of road construction, during the first World World War, every meter of road had to be carved through the mountains by hand. The internees at Edgewood did this labour throughout the year, sometimes in the coldest months, from dawn to dusk, using only these handheld tools to break the rugged West Kootenay terrain.

* * *

All of these factors lead to a state-sanctioned campaign to find and prosecute anyone with socialist sympathies. This led to a ban on literature, organizations, and even associations perceived as communist. This included some labour unions, several foreign language papers, specifically those that were left-leaning, and some foreign organizations. While British and native-born Canadians were affected by these bans, immigrants from Russian, Ukraine, and Finland were the majority of those who were arrested and fined.

Even though the war had ended, several camps remained open after the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Several 'enemy aliens' who were caught with "Red" literature or engaging with illegal organizations were interned, and some were even deported. In 1915, several of the leaders of the Ukrainian Democratic Socialist Party (UDSP) were arrested and interned, despite being Canadian citizens.

The prominence of leftwing organizations such as the UDSP in Ukrainian communities, and Ukraine's relationship with the new Soviet Union only exacerbated lingering xenophobic sentiments as the first "Red Scare" began in the winter of 1918. Many of the Ukrainians that were deported in the immediate post-war period were those accused of being "Red" agitators. In 1920, an article in the Vancouver World stated that 100 "Reds" were taken to the Kapuskasing camp and subsequently deported.1

While the general public still held strong anti-immigrant prejudices in the years following the war, some of the most vocal objectors to 'enemy aliens' were veterans who had just returned home from service abroad.

10. Seizing what was Earned

1915-1916

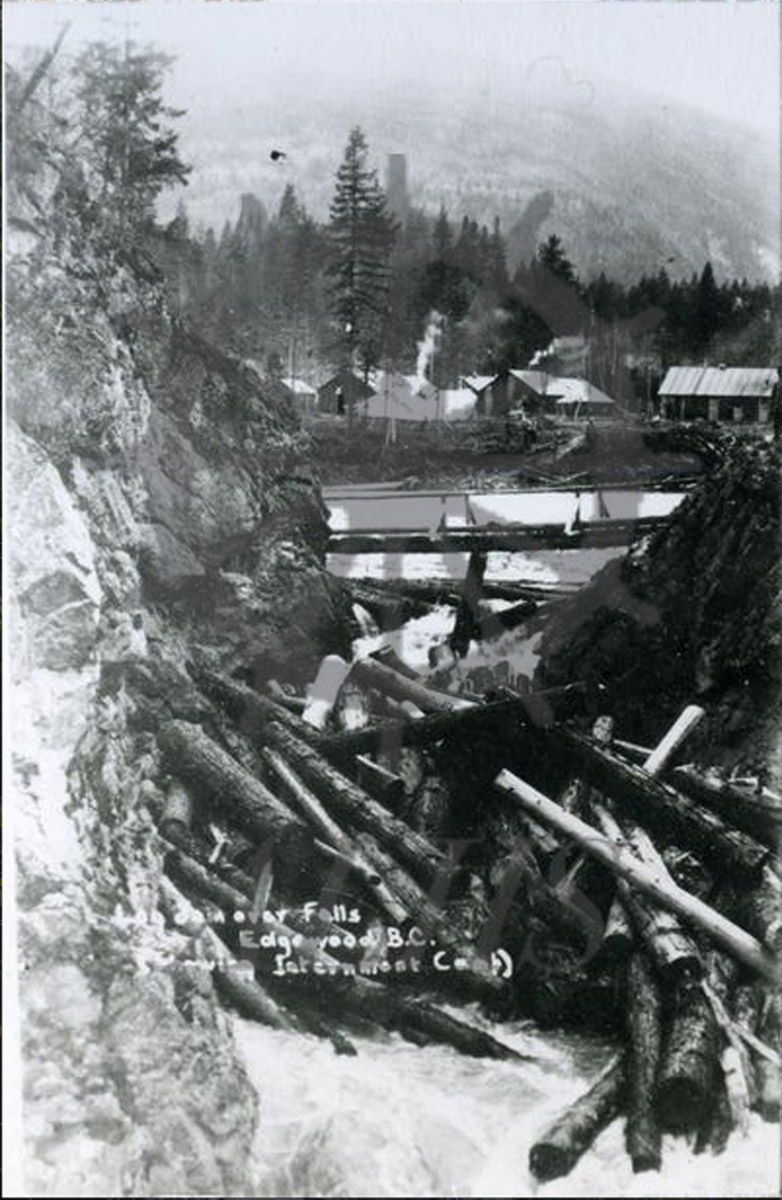

This shot of the Edgewood camp looks across the creek where dozens of cut logs have jammed the narrow channel. On a number of occasions, internees at Edgewood refused to work on account of the poor quality and insufficiency of the food. The supervising road engineer, John Black, blamed the problem on the camp commandant, Captain Harvey, who he viewed as being too soft on the internees. However, Black was impressed with the work of a junior officer who took it upon himself to impose a punishment of six days on a diet of only bread and water for anyone who refused to work and threatened resistant internees with beatings. The result was a camp-wide strike.

The image that Black paints of the internees' resistance is quite different from the one printed in the newspapers. In June of 1915, the Vernon News reported, "[The internees] are giving no trouble to the authorities, and work steadily and well, accomplishing their daily tasks in a manner that calls forth praise from those who are in charge of them."1

* * *

To the returned veterans, it was unconscionable that they be expected to work alongside 'enemy aliens', especially in any industries considered vital to Canada's war effort. Securing employment for returned soldiers was a considerable concern for the government and the public. Organizations such as the Great War Veterans Association quickly gained considerable influence and support for their initiatives. Often their goals aligned with those of the federal government.

One of the largest issues for the government early in the war was the question of the German and Austro-Hungarian Canadian vote. Many in Canada believed that the highest duty to citizenship was serving Canada and the British Empire in the war, but also that Canadians who originated from enemy nations should not be forced to take up arms against their former countrymen.

Since 'enemy aliens' could not perform the duties of citizenship that society expected of them, many government officials, veterans associations and much of the public felt that they should not be allowed to weigh in on issues regarding the war - Namely, conscription. Prime Minister Borden and his government wanted to implement conscription, but they feared that naturalized German and Ukrainian Canadians would vote against it. Organizations such as the GWVA and the press were swift to publicise the issue, pressuring the government to decide what they would do about the 'enemy alien' franchise.

In August 1917, the War Time Elections Act was passed alongside the Military Service Act, which introduced conscription. The War Time Elections Act is most often remembered as the first bill that gave the franchise to women, specifically the wives, mothers, and sisters of soldiers serving overseas. However, it also stripped the franchise from any 'enemy aliens' who were naturalized within the last 15 years. German and Ukrainian Canadians were caught between a rock and a hard place. Much of the Canadian public largely viewed them as freeloaders benefitting from their exemption from service while other Canadians were fighting in the trenches, but even if they had wanted to enlist, and many did, 'enemy aliens' were prohibited from doing so.

Due to this, the Great War Veterans Association, and many civilians supported the idea of conscripted 'enemy alien' labour, and were persistent in pushing the government to impose it. However, the federal government resisted. Primarily due to the fact that organized labour would violently oppose such a measure, and that this opposition would result in strikes that would ultimately slow production.3

As the war drew to a close, the GWVA and other veterans associations were equally insistent that all 'enemy aliens' be deported. In December 1918, the Vancouver World reported that in Victoria the Comrades of the Great War passed a resolution calling for the deportation of all enemy aliens in Canada.4

In Hamilton, Ontario, a February 1919 meeting of the GWVA urged the Canadian government to immediately deport all 'enemy aliens' and other undesirables. A few months later, a delegation of several hundred GWVA members came before the Manitoba premier at the parliament building demanding that all 'enemy aliens' in Manitoba be interned, swiftly deported, and any money or property worth over $75 be seized and instead used for the benefit of widows and orphans of soldiers.5

An article published in early 1919 in the Ruthenian Canadian explains the turmoil faced by the Ukrainian Canadian community during this time,

The Ukrainians were invited to Canada and promised liberty, and a kind of paradise. Instead of the latter they found woods and rocks, which had to be cut down to make the land fit to work on. They were given farms far from the railroads, which they so much helped in building - but still they worked hard and came to love Canada. But liberty did not last long. First, they were called "Galicians" in mockery. Secondly, preachers were sent amongst them, as if they were savages, to preach Protestantism. And thirdly, they were deprived of the right to elect their representatives in Parliament. They are now uncertain about their future in Canada. Probably, their [property] so bitterly earned in the sweat of their brow will be confiscated.6

11. Forgetting the Trauma

Arrow Lakes Historical Society 2016.013.5.5

1915

A snowy view beyond the small river ravine shows the Edgewood internment camp. The Edgewood camp closed permanently on September 23 1916 after just over a year of operation. For 13 months, internees lived in the tents and small log structures at camp, while working on the Monashee to Edgewood Road. The reports of poor clothing, insufficient food, and threats of physical punishment, as well as these photos of the camp in a frozen winter landscape, give us only a small idea of what life at Edgewood was like for the men who were imprisoned here. After the camp closed, the majority of the internees were returned to the Vernon internment camp, which was the second-last camp to close in Canada in 1920.

* * *

World War I internment operations also set a precedent for another dark period in Canadian history. In World War II, the Canadian government pulled from the blueprint that had served them so well during the Great War, and commanded the internment of much of the country's Japanese-Canadian community. Unlike internment in the First World War, entire Japanese-Canadian families were interned regardless of age, sex, or citizenship status. Road construction was one of the primary labour projects assigned to Japanese internees, much like it had been for the Ukrainians before them.

Studying World War I internment operations is challenging for historians today as well. In addition to the reluctance of many survivors of internment to discuss their experiences, the government also destroyed many of their internment records in the 1950s. Few records and first-hand accounts from survivors remain today.

In the years after the Second World War, the Ukrainian Canadian community began to seek acknowledgement and redress for the wrongs the government committed against them during the war.

In November 2005, the Internment of Persons of Ukrainian Origin Recognition Act, was passed, obliging the Government of Canada to negotiate “an agreement concerning measures that may be taken to recognize the internment” for educational and commemorative projects. The enactment initiated negotiation work with the Ukrainian Canadian Congress, the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association and the Ukrainian Canadian Foundation of Taras Shevchenko.

In May 2008, representatives of the Ukrainian Community reached an agreement with the Government of Canada providing for the creation of an endowment fund to support commemorative, educational, scholarly and cultural projects intended to remind all Canadians of this episode in our nations’ history.

The Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund exists to support projects that commemorate and recognize the experiences of all the ethno-cultural communities affected by Canada’s first national internment operations of 1914-1920.

At Edgewood, there is little evidence of the camp's existence. The grounds are now a baseball diamond, and the only indication of the site's history is the plaque we visited at the start of this tour. The plaque, like many similar ones across the country, is a direct result of the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association's work to ensure all these sites are recognized.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

2. Coming to Canada

1. John Douglas Belshaw, "5.4. The Clifford Sifton Years 1896-1905" in Canadian History: Post-Confederation (2nd ed) (Victoria, BC: BCcampus, BC Open Textbook Project, 2016), online.

3. Register and Report

1. Lubomyr Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1929 (Kingston, ON: Kashten Press, 2001), 6.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 7.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 11.

4. Mounted Guards

1. Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the enemy alien experience (Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 137. E-book.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 41.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 70.

5. The Press

1. Kordan, 163.

2. The Globe, "Alleged German Spies and Supplies Seized," Oct. 16, 1914, online.

3. The Globe, "Alien enemies," (Toronto, ON), 29 March 1918. In Lubomyr Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1929 (Kingston, ON: Kashten Press, 2001), 49-50.

6. The Value of Labour

1. "Alien Prisoners May Be Employed" Vernon News (Vernon, BC), May 6, 1915, online.

2. "Favor Internment of Alien Enemies - Royal City Aldermen Deal With Nanaimo City Council's Resolution" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Oct. 3, 1916, online.

3. "Value of Internment Work" Crossfield Chronicle (Crossfield, AB), Dec. 31, 1915, online

7. Ukrainians Fighting for Canada

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 98.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 98.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 35.

4. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 98.

5. Lubomyr Luciuk, "Filip Konowal, VC" The Canadian Encyclopedia, April 24, 2015, online

8. Crunching Numbers

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 20.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 20.

3. Christopher Guly, "Report details Ukrainian Canadian losses during internment" in Lubomur Luciuk (ed.) Righting an Injustice (Toronto, ON: The Justinian Press, 1994), online.

4. Guly, online.

9. After the War

1. "Canada deports enemy radicals" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Jan. 20, 1920, online.

10. Seizing what was Earned

1. "Monashee-Edgewood Roadwork is Satisfactory" Vernon News (Vernon, BC), June 24, 1915, online.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 218.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 222

4. "Would Expel Enemy Aliens" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Dec. 21, 1918, online.

5. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 105.

6. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 106.

Bibliography

Belshaw, John Douglas. "5.4. The Clifford Sifton Years 1896-1905" in Canadian History: Post-Confederation (2nd ed), Victoria, BC: BCcampus, BC Open Textbook Project, 2016.

Guly, Christopher. "Report details Ukrainian Canadian losses during internment" in Lubomur Luciuk (ed.) Righting an Injustice (Toronto, ON: The Justinian Press, 1994), PDF.

Kordan, Bohdan S. No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the enemy alien experience. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016. E-book.

Luciuk, Lubomyr. "Filip Konowal, VC" The Canadian Encyclopedia, April 24, 2015. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/filip-konowal

Luciuk, Lubomyr. In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians. 1914-1929, Kingston, ON: Kashten Press, 2001. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/resources-bibliography.cfm

**Newspaper Articles**

"Alien enemies," The Globe (Toronto, ON), 29 March 1918. In Lubomyr Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1929 (Kingston, ON: Kashten Press, 2001), 49-50.

"Alien Prisoners May Be Employed" Vernon News (Vernon, BC), May 6, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles_by_camp.cfm?lid=13

"Alleged German Spies and Supplies Seized" The Globe, Oct. 16, 1914. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles_by_camp.cfm?lid=14

"Canada deports enemy radicals" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Jan. 20, 1920. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/20/1920-01-20-VW-Canada-Deports-Alien-Radicals.pdf

"Favor Internment of Alien Enemies - Royal City Aldermen Deal With Nanaimo City Council's Resolution" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Oct. 3, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/14/1916-10-03-VW-Favor-Internment-of-Alien-Enemies.pdf

"Monashee-Edgewood Roadwork is Satisfactory" Vernon News (Vernon, BC), June 24, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/13/1915-06-24-VN-Monashee-Edgewood-Roadwork-is-Satisfactory.pdf

"Value of Internment Work" Crossfield Chronicle (Crossfield, AB), Dec. 31, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/13/1915-12-31-CROSC-Value-of-Internment-Work.pdf

"Would Expel Enemy Aliens" Vancouver World (Vancouver, BC), Dec. 21, 1918. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/14/1918-12-21-VW-Would-Expel-Enemy-Aliens.pdf