Partner City

Chichén Itzá

Wonder of the New World

Deep in the jungles of the Yucatan can be found the ruins of the ancient city of Chichén Itzá, one of the best known and most spectacular examples of Maya Civilization's achievements in architecture, art, math, and science. The city was the main political and commercial centre of the Northern Maya Lowlands from the Late Classic period and into the early parts of the Postclassic (roughly 750 CE to 1000 CE). Evidence of the cosmopolitan nature of the society that built this city can be seen by the fusion of distinct architectural styles that came from distant Central Mexico, and from across the Mayan Lowlands. The vast Xtoloc cenote contributed to the site's religious importance, and construction of the many great pyramids, temples, observatories, and ball courts spread outwards from it. Chichén Itzá grew in prominence around the 9th Century CE, coinciding with the fragmentation of the major Mayan power centres of the Southern Lowlands, and the decline of her local rivals, Yaxuna and Coba. Following centuries of rise, peak and decline, it is thought the Chichén Itzá was finally conquered by her rival Mayapan in the 13th Century. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th Century, it is unclear if people were still living at the site, though construction of monumental structures had halted centuries before. A party of Conquistadores set up their base at Chichén Itzá. The Spanish rapidly alienated the local Maya, and found themselves besieged, leading to a bitter battle amongst the ancient ruins. The Spanish fled, but returned some years later and conquered the entire Yucatan Peninsula. The site of the ancient city became a cattle ranch. The ruins were reclaimed by the jungle and forgotten by the outside world. It wasn't until 1843 that an American explorer and diplomat, John Lloyd Stephens, described the ruins in a book, igniting the enduring global fascination with Chichén Itzá. Many subsequent expeditions to the site by archaeologists, anthropologists, and treasure seekers followed, beginning in the 1860s. They resulted in the creation of the historic images you see in this collection.

Explore

Chichén Itzá

Then and Now Photos

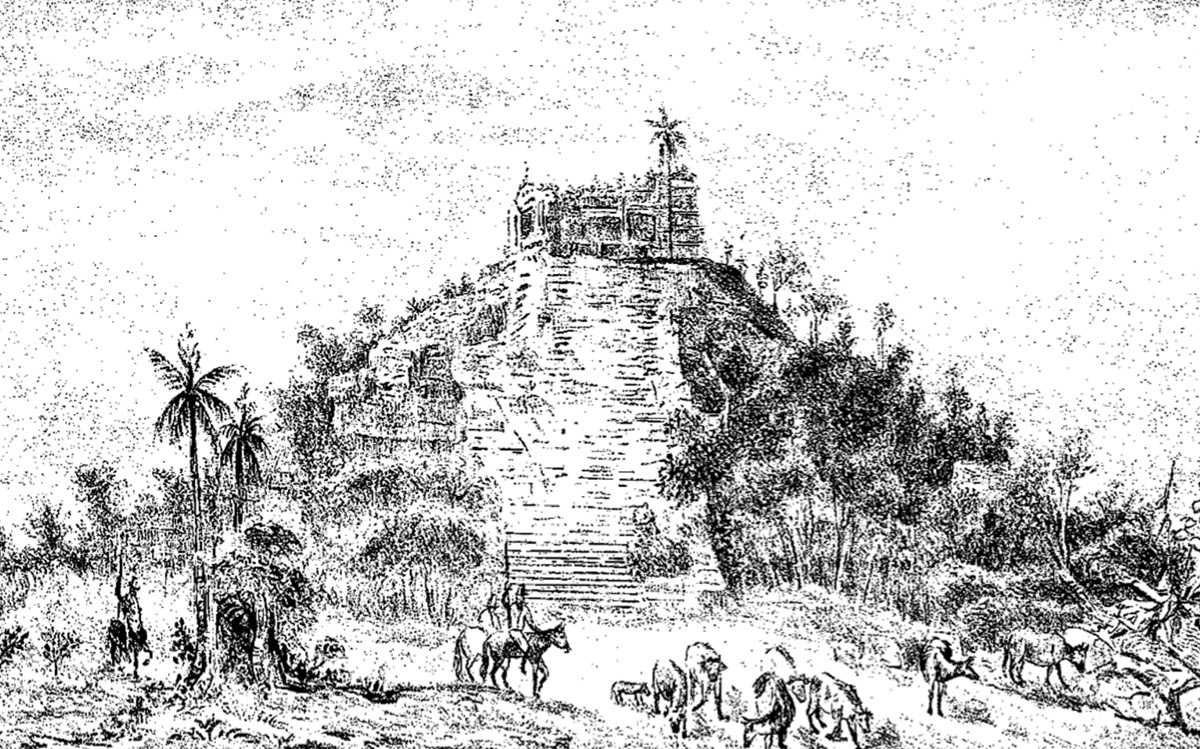

An Early Depiction

Stephens 1843:312 "Castillo, Chichén Itzá

1843

One of the first modern depictions of the site of Chichén Itzá, taken from Stephens groundbreaking book. When they arrived much of the jungle had been cleared away by local herds of cattle that had been grazing there.

The Temple of Kukulcan

Catherwood 1844: "Plate XXII Teocallis, at Chichén Itzá"

1844

An early drawing of the Castillo, or Temple of Kukulcan, which dominates the site of Chichén Itzá.

The building sits on a rectangular platform 55.5 meters wide and 24 meters high. Precision and intention are part of the essence of the building, each side of the pyramid has a grand staircase, 91 steps per side and one more that leads to the upper temple, giving 365 steps, one per day of the year.

Stone balustrades flank each stairway, and at the base of the north stairway are two colossal feathered serpent heads, effigies of the god Kukulcán. It is on these stairs, and very particularly on their parapets or balustrades, where the shadows of the edges of the superimposed platforms or bases that make up the great building are projected around the equinoctial day, thus configuring the image of the body of the serpent, which As the hours go by, it seems to move down and end at the aforementioned stone head located at the bottom base of the stairs.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

View of the Castillo

Peabody Museum Archives, Harvard University

1892

A view of the Castillo looking towards the southeast.

The Shadows of the Serpent

A. D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library

1895

A man and woman by one of the serpents at the foot of one of the stairways to the top of the Castillo.

Testimony to the amazing advancements of the Maya in architecture and astronomy is the phenomenon of "lights and shadows" that takes place on the north staircase of the Castle during the Spring Equinox on March 21 and the Autumn Equinox on September 21. Around three in the afternoon on the days of the equinox, the sun casts seven triangles of light on the balustrade on the northeast side of the Castle. These begin to move up and down along the balustrade to form the silhouette of a snake.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

The Cenote Below

Getty Research Institute, 94.R.31

1882

In 1997, the universities of Minnesota and San Francisco conducted radar studies in the area that revealed a hidden cenote under the El Castillo pyramid at Chichén Itzá. In 2015, the Institute of Geophysics of the National Autonomous University of Mexico carried out magnetic resonances that allowed it to graphically represent the cenote, eight meters hidden under the pyramid. In 2017, the Great Maya Aquifer research team began explorations in nearby caves to discover an entrance to this body of water. However, the entrance was blocked by stones that were probably placed there intentionally. It is believed that this cenote was kept hidden because it represented the center of the world.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com.

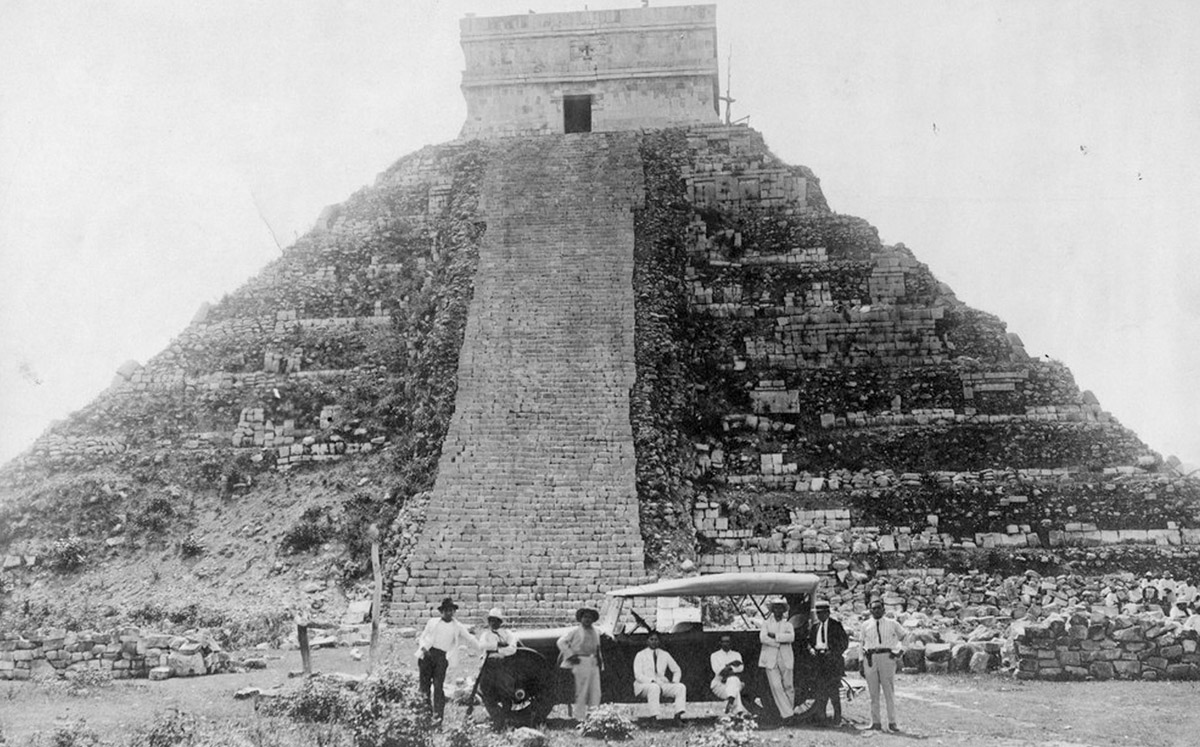

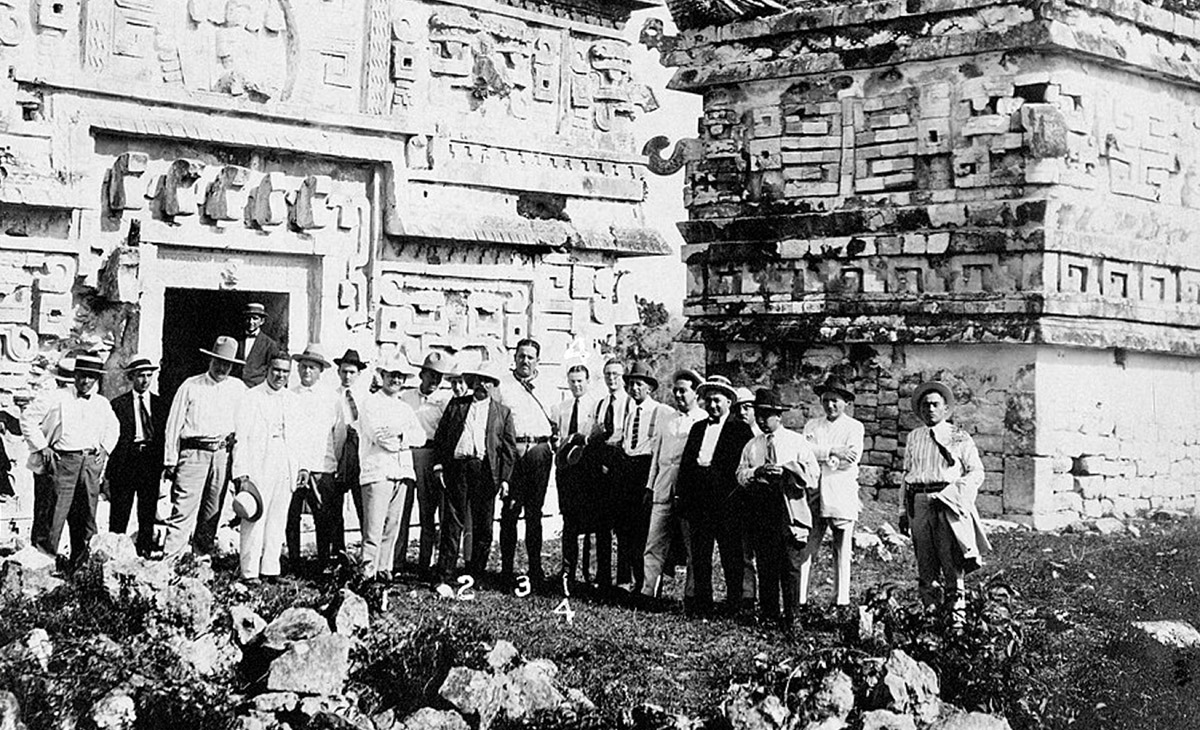

Governor's Visit

1924

The State governor and his retinue pose for a photo during a visit to Chichén Itzá.

The Ball Court

Field Museum Library Collection

1899

This is the famous Ball Court of Chichén Itzá. At 166 metres long and 70 metres wide, it is the largest Mayan ball court that has been discovered.

It has remarkably perfect acoustics, so that if one whispers at one end of the court, it can be heard at the other. This effect is barely impeded by wind or weather conditions.

Temple of the Jaguars

A. D. White Architectural Photographs Collection at Cornell University Library

1895

The Temple of the Jaguars was built on the east wall of the Ball Game. An interesting mosaic repeats along the length of the frieze: two jaguars advance, from different directions, towards a round shield. The upper tableau is filled in with the bodies of two plumed serpents, with their heads at the edges of the frieze and the tails interlocked in the center.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

The Ball Game

A. D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library

1899

It has only been possible to partially reconstruct the rules of the ball game, thanks to pictorial representations and stone monuments. We know that at the beginning of the game the ball was thrown onto the court by hand, and that from that moment it could only be touched with the hips and thighs. We do not know the number of players, the scoring system, or how the winner was decided; according to information in the Popol Vuh we can infer that the game could be played one on one, in pairs, or in teams. In the depictions, the players appear in various attitudes, showing the different plays in this contest.

The ball for the game was made from liquid latex extracted from rubber trees. When heated, the resin formed threads that were first rolled up and then squeezed by hand or pressed in a mould.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

Restoring the Ball Court

1932

Restoration work underway on the Temple of the Jaguar overlooking the Ball Court. The remarkable acoustic properties of the site have enthralled people since the site's modern discovery. In 1931 the acoustic engineer Leopold Stokowski spent days at the site trying to unravel the principles that allowed sound to travel so effectively, so that he could use them in his theatre designs.

He failed to discover the Mayans' secret. It continues to defy the best efforts of scientists and engineers to this day.

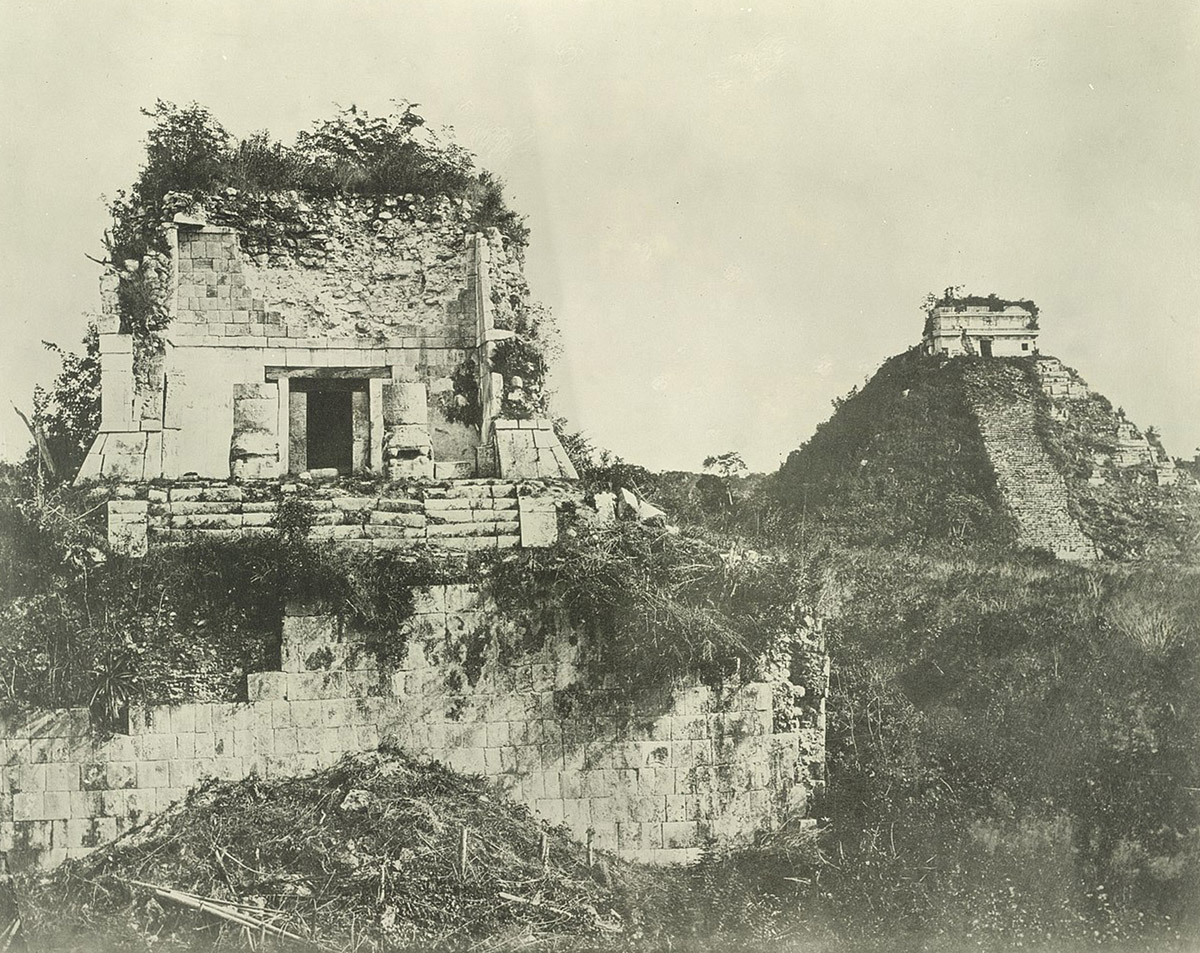

The Nuns' House

Percival Maudslay, A Glimpse at Guatemala

1899

The House of the Nuns or Nunnery, are the names given to certain Maya buildings, for example those in Uxmal. The Spanish conquistadors were the ones who chose most of the buildings' names.*

The House of the Nuns and the Church are the names of two constructions of the old Chichén Itzá, which date from the Classic period and occupy the southern part of the site.

The Nunnery has particular characteristics, one of them being a construction of Puuc style, however, the facade of the building itself, which faces east, is not of the style of the region, but of another classic Mayan style known as "Chenes" style because it is frequent in the region so called, in the northeast of the State of Campeche.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

Nunnery Friezes

1917

A man sits in front of the elaborate friezes of the so-called Nunnery.

Clearing the Jungle

1923

Workers clear the jungle away from the columns at the Temple of the Warriors.

The Iglesia

Percival Maudslay, A Glimpse at Guatemala

1899

The Church is a Temple dedicated to Chaac, god of rain. The building its located in the oldest side of the whole Archaeological Site of Chichén Itzá, right next to the “Nuns Complex” or “Nunnery”. It consists of only one chamber and one door that gives acces to the main part of the building. It’s similar to a rectangular chapel, and that’s why the Spaniards named it The Church.

This building stands out from others because of its preserved state, you can see the details on the bas-relief and stone carvings. The most notable motifs of the decoration are the masks of the rain god with a hooked nose protruding from them, located in the corners.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

The Caracol

1924

The so-called Caracol or Observatory is a structure built in the form of a larger circular tower set on a platform with a central staircase. The base sits on another rectangular platform, decorated with a cornice with rounded corners at the top. El Caracol is actually built with three superimposed buildings.

Its priests, the greatest astronomers of the time, managed to calculate with great precision the solar and lunar eclipses, the rising and setting of Venus and the movements of stars and planets, as well as the solar year.

Even today, scientists are amazed by the development of Mayan astronomy. For the ancient Maya, astronomy and cosmogony were closely linked in their mythical conception of the universe.

Known as the "Lords of Time", the Maya were the only ones to raise to the rank of gods not only the idea of time, but also the periods into which it is divided. They represented time as supernatural beings whose mission was to maintain order in the universe. The Mayan gods of time completed their life cycle in a constant circular movement beginning with their birth, developing with the manifestation of their characteristics, and ending with their death. Then they were born again and a new cycle of birth and death began.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

Governor at the Nunnery

1924

The state governor and his retinue pose for a photo outside the spectacular friezes of the Nunnery.

Red House

1925

The Red House or Chichanchob.

Chichanchob at Chichén Itzá is the largest and best preserved of the four buildings surrounding the main plaza. Chichanchob translates as "small holes" from the Maya. The name is given after the small holes in its raised ridge. It is also commonly known as Casa Colorada o Casa Roja (Red House), due to a strip painted in red inside the vestibule or first bay.

This structure itself corresponds to the Puuc style, although later the Itzáes built a small ball court attached to the back wall or east side of the structure.

The final inscription of "un tun" was found inside the Chichanchob building that refers to the year 850, which allows to establish the antiquity of the building.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

Platform of the Skulls

1923

The Tzompantli of Chichén Itzá, or Platform of the Skulls, is dedicated to the dead, and can be found in different Mayan Archaeological sites. This one is one of the oldest Tzompantli found ever. Habitants of Chichén Itzá would gather long wooden beams in which they would hang their enemies' heads. Archaeologists have found buried figures of Chaac Mool in the Tzompantli of Chichén Itzá, along skull offerings and a broken ring from the Ball Game court.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

House of the Deer

A. D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library

1895

Also known as The Temple of the Deer, this building is now very much destroyed. It must have been similar to the Chinchanchob, but more than half of the structure has collapsed.

Over the roof, the remains of the crest are barely conserved. The name of the temple, according to tradition, comes from a painting of a deer in the interior that, as time passed by, has faded away. From what remains to be seen today it’s possible that the building suffered from a water tract that washed away the stucco from the walls, where this painting might have been.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

Ruins of the Ossuary

1923

Vegetation has been removed from the steps to the ruined Ossuary.

The Ossuary is one of the most complex buildings on site. It is known to be built over a deep cave. It is possible that this cave was considered a door to the underworld. Its architecture is very similar to the Pyramid of Kukulkan, with 4 staircases and an upper temple.

The most remarkable aspect of the Ossuary is its bust decoration. Full of different bas-relief snakes, birdmen, men with god-like masks and other representations.

- Excerpt from ChichenItza.com

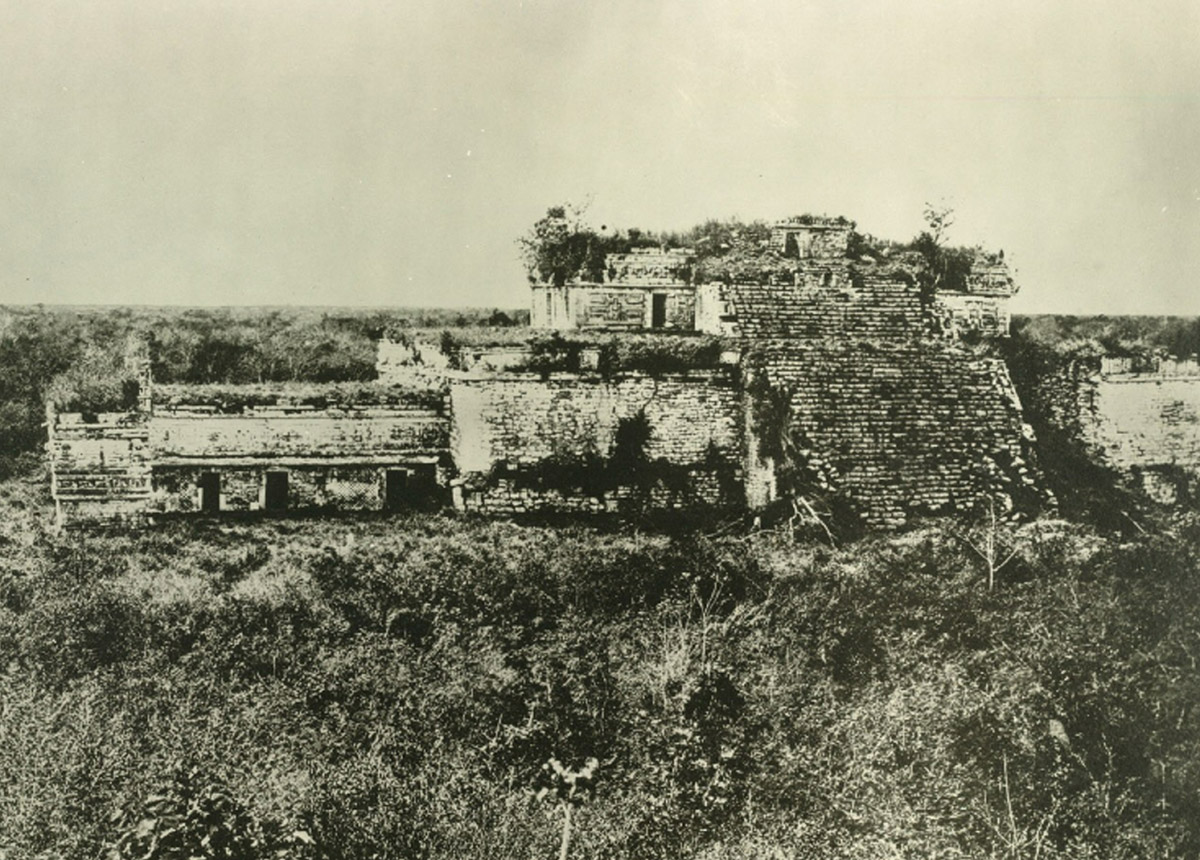

Restoration of the Castillo

A. D. White Architectural Photographs, Cornell University Library

1895

This photo of the Castillo shows early restoration work has cleared the jungle away from half of the pyramid.