Walking Tour

Characters of the Stampede

The Origins of Calgary's Favourite Event

Elyse Abma-Bouma

For thousands of years people have come here to this in the Bow valley at the junction of the Bow and Elbow Rivers, Calgary has been a place where people from across the prairies gathered to meet, hunt, and trade.

Prior to the 1600s the First Nations in the area did all of their bison hunting and travel on foot. When the Spanish reached what is now Mexico they brought with them horses which quickly became a useful tool to indigenous populations. Eventually, horses made their way North through escape and trade changing hunting and transportation for the Plains First Nations

When Europeans settled in Southern Alberta they were intrigued by the bison and began to hunt the bison for their coats. While the First Nations had been strategically hunting the buffalo and using every part of the animal, Europeans hunted the herds en masse fur and drove them to the edge of extinction.

Without the bison the Bow Valley was left with rolling hills and empty fields, so ranching and agriculture became a feature of the region. Soon cattle were brought in replacing the bison and vast ranches were everywhere.

Ranching life was the height of the Western aesthetic. Roping, busting broncos, cowboy hats, and wrangling became how easterners and others outside of the prairies envisions the 'Wild West.' The Calgary Stampede has become a preservation of cowboy life out on the prairies, imprinting a 'Wild West' past on a modern present.

1. Beginnings

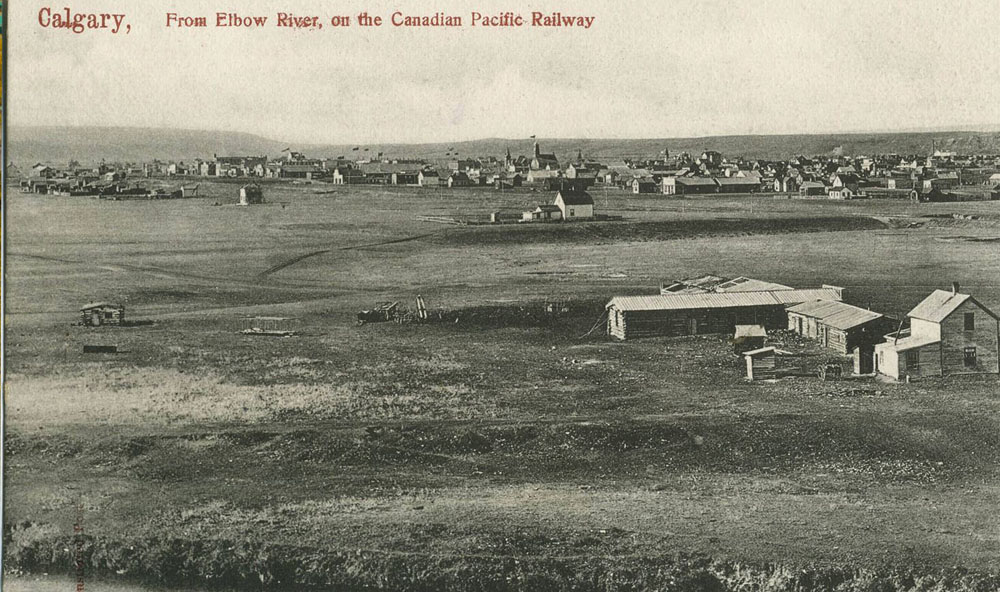

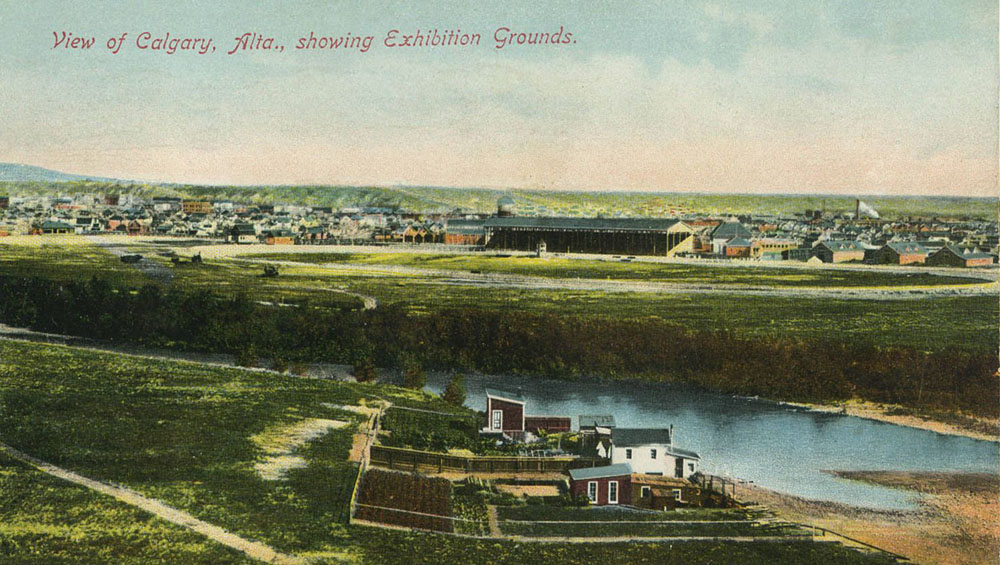

Calgary Public Library pc 1680

1904

Here is Calgary at beginning at time when the age of ranching was coming to an end. At the turn of the 19th century Calgary was about to experience great growth and expansion. You can see the scattering of homes, churches, and businesses that made up early Calgary.

The Calgary Stampede is one of the city's defining events and, in many ways, the embodiment of Canadian Frontier culture. Now known as the "Greatest Outdoor Show" the Calgary Stampede is the legacy and brainchild of cowboy and 'Wild West' performer Guy Weadick.

* * *

The first Calgary Stampede was held in 1912. During the early 20th century southern Alberta experienced an increase in immigration from America, as a result, the Americans brought with them 'Frontier Culture' and a fantasization of the "West" from the travelling 'Wild West' shows popular in the United States. Guy Weadick initially proposed the Calgary Stampede as an “authentic western experience” to bring together southern Alberta in the spirit of the 'West'.1

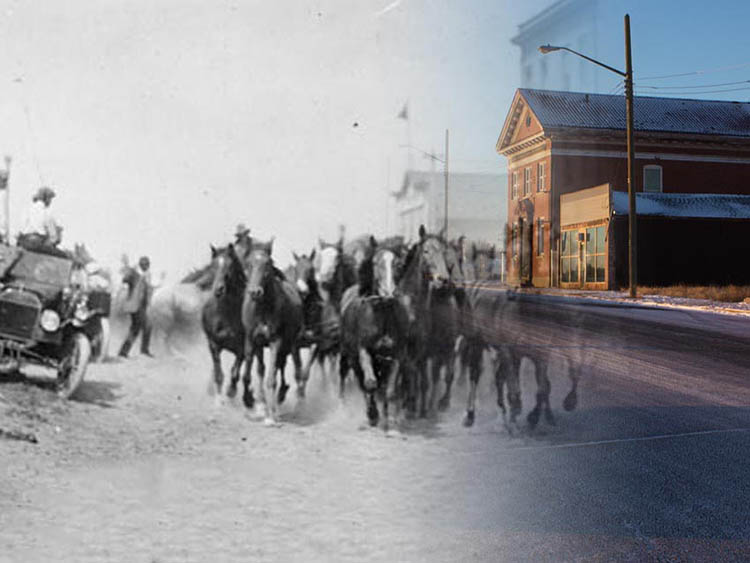

Paired with different views of the where Stampede grounds now stand, we will explore the lives of some of the earliest competitors and officials involved in the world renowned rodeo. All of these characters interacted with these grounds and, on this spot, they made history.

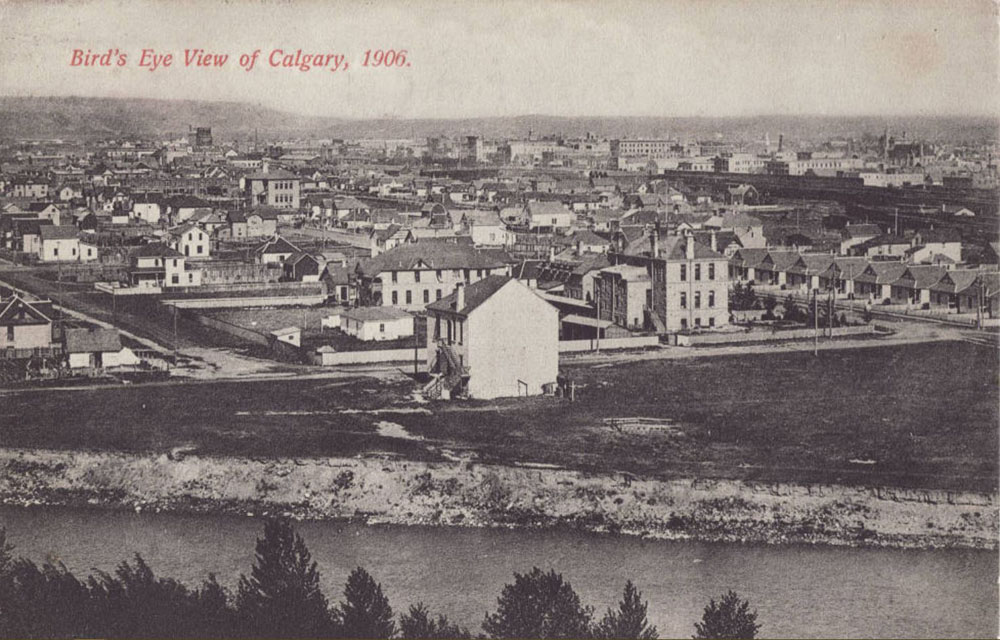

2. The Founder

1906

Guy Weadick is best known for creating the Calgary Stampede. Hailing from Rochester, New York, Weadick had been a Wild West performer, rancher, and planned the first Stampede all before his 30th birthday. Though he eventually fell out of favour with the planning committee of the Stampede, his legacy lives on to this day. From this spot one you can see the landscape where Weadick imagined his Stampede and made his vision come to life.

* * *

As a young man Guy Weadick learned his skills as any cowboy does, by working on a ranch. Between being a ranch hand in New York and performing in 'Wild West' shows throughout the United States, Weadick developed a love for the cowboy life. Having toured across America he came to Calgary hoping to put his roping and wrangling skills to practical use again. The idea for the Stampede was to marry the event aspect of 'Wild West' shows with an authentic experience of working on a ranch. Weadick and his wife Florence LaDue, who was a “fancy roper” and fellow 'Wild West' performer alongside Guy, moved to Calgary around 1908. It was here that Weadick would discover his talent for promotion and create the Calgary Stampede.1 Weadick first pitched his idea for the Stampede to the Canadian Pacific Railway commissioner in 1908. While the commissioner liked the idea, he told Weadick that Calgary was not yet ready for such an event because the city could not feasibly host such an elaborate event. This age saw Calgary's population explode and the economy expanded dramatically. Calgary would soon be capable of hosting Weadick's dream.

In 1912 Weadick pitched the idea to Calgary’s “Big Four” (the most influential businessmen of the time) and they were so inspired by his vision and charisma that they agreed to finance the Stampede providing Weadick with a $100,000 line of credit, over $2 million in today's currency. He was 27-years-old and planned the whole event in just a few months, but Weadick’s tireless work paid off and the first Stampede was a great success with a competitors from across North America and massive support from Calgary's residents and businesses.2

Guy Weadick’s ambition for parading the 'Western Spirit' was admirable and surprisingly inclusive. Weadick’s 'Wes't included anyone who lived in the west regardless of gender, race, or status. In creating his first Stampede Weadick went against the wishes of the Indian Affairs department and sent letters to the Treaty 7 First Nations bands inviting them to participate in the rodeo competitions. Women’s events were also hosted, although they were not permitted to compete for prize money and their events were less publicized. Weadick envisioned a West united under the authentic Stampede experience and he went out of his way to make sure of the authenticity.4 Between the Great War, economic turmoil and the rapid industrialization of Calgary, the Stampede was placed on a backburner. In an effort to boost morale after the post-war recession, the stampede was reinaugurated in 1923 and became an annual event that continues to this day.3

Unfortunately, Weadick’s time as the Stampede manager ended bitterly. The Great Depression of the 1930s cratered Calgary's economy and, as a result, the Stampede had less funds. To save the Stampede it was joined with the Calgary Exhibition and Weadick believed that the integrity of the Stampede experience was compromised. The strain wore on Weadick, who became prone to angry outbursts and slandered the Stampede board behind their backs. The board dismissed him in 1932. Though Weadick filed a lawsuit for wrongful dismissal, nothing ever came of it and Weadick was never involved with the Calgary Stampede again. He retired to his ranch where he wrote and lived until his death in 1953.5

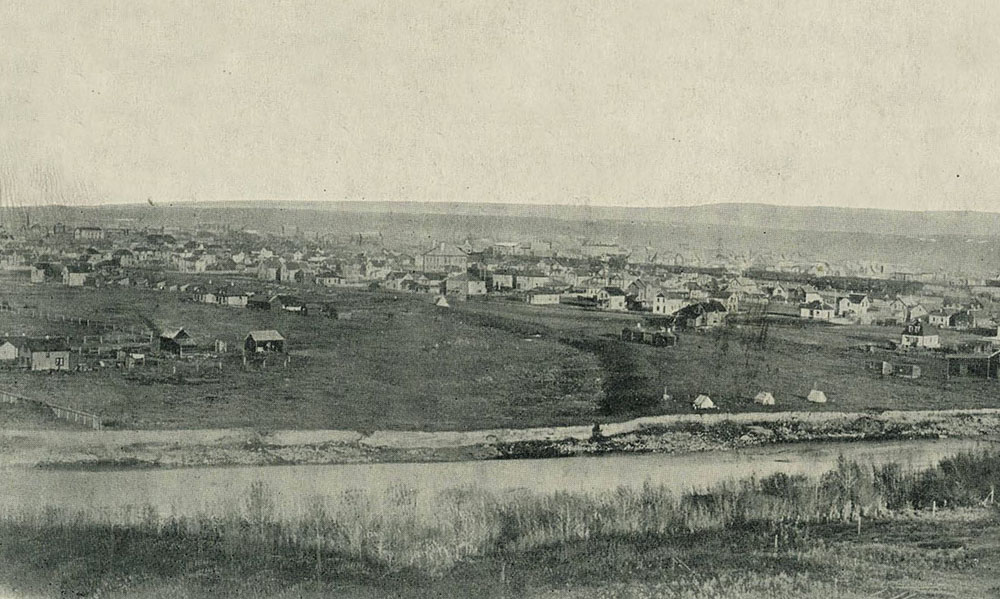

3. The Legend

1905

Tom Three Persons became one of the most legendary cowboys of the stampede, and his exploits setting the standard by which future competitors were measured. He was Niitsitapi, part of the Blackfoot Confederacy, and his fame and reputation continue to embody the ideal of the "Frontier Cowboy". From this spot you can see the sprawling Stampede grounds where Tom Three Persons masterfully rode broncos and roped steers.

* * *

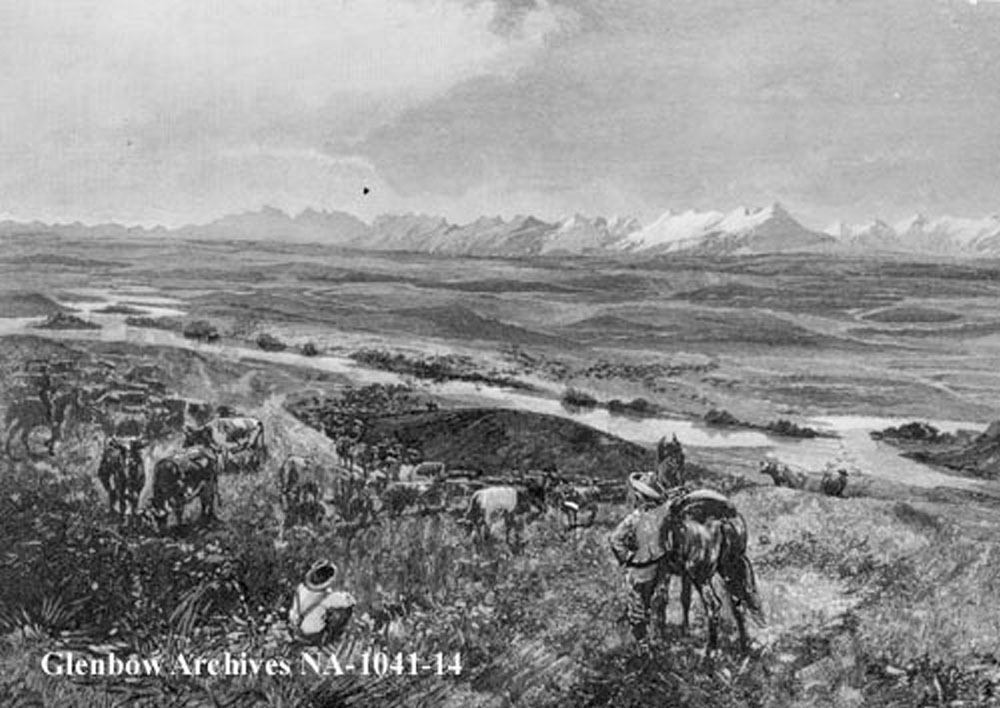

4. The Rancher

1882

This drawing shows some Northwest Mounted Police climbing Scotsman Hill. This very landscape is where rancher John Ware made his life riding these very hills.

John Ware was a legend of the 'West', surrounded by speculation and myth his life attracted the attention of prominent figures such as Grant MacEwan who wrote his story. As the child of slaves in Georgia (and perhaps a slave himself), Ware was an unlikely candidate to create two profitable ranches in Southern Alberta. Though he was not exempt from experiencing the racism of the settlers, his fellow ranchers deeply respected him and spoke highly of his work ethic and ranching skills.

* * *

5. The Queen

1900s

Since 1947 Calgary has chosen a Stampede Queen to represent Calgary at the Stampede and across North America. In 1954, nineteen-year-old Evelyn Eagle Speaker of the Kainai nation was competed for the title of Stampede Queen. She won the title and remains the first and only indigenous woman to hold the title. Eagle Speaker desired to overcome racist stereotypes of indigenous people, and demonstrate to Canadians and people around the world that embodied the 'Western Spirit' as much as any white person.1

* * *

Endnotes

1. Beginnings

1. Mary-Ellen Kelm. "Manly Contests: Rodeo Masculinities at the Calgary Stampede." The Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 4 (2009): 714-29.

2. The Founder

1. Brian W. Dippie. "Charles M. Russell and Guy Weadick: A Match Made in Stampede Heaven." Alberta History 60, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 15-16.

2. Dippie, 16.

3. Dippie, 20.

4. Mary-Ellen Kelm. "Manly Contests: Rodeo Masculinities at the Calgary Stampede." The Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 4 (2009): 729.

5. Max Foran. "A Lapse in Historical Memory: Guy Weadick and the Calgary Stampede." American Review of Canadian Studies 39, no. 3 (2009): 256-65.

3. The Legend

1. Robert Kossuth. "Busting Broncos and Breaking New Ground: Reassessing the Legacies of Canadian Cowboys John Ware and Tom Three Persons." Great Plains Quarterly 38, no. 1 (2018): 58.

2. Kossuth, 69.

3. Hugh A. Dempsey. Tom Three Persons. Purich Publishing (Saskatoon), 1997. 36.

4. Mary-Ellen Kelm. "Manly Contests: Rodeo Masculinities at the Calgary Stampede." The Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 4 (2009), 740.

5. Kossuth, 60.

4. The Rancher

1. Kossuth. 58.

2. Kossuth, 58

3. Kossuth, 61

4. Kossuth, 26

5. Kossuth, 63

5. The Queen

1. Alvin Finkel, Sarah Carter, and Peter Fortna. The West and Beyond New Perspectives on an Imagined Region. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2014. 113-155

2. Finkel et Al., 137.

3. Jennifer Hamblin. "Queen of the Stampede: 1946-1966." Alberta History 60, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 33-43.

4. Finkel et Al.,138-40.

5. Hamblin, 38.

6. Hamblin, 40.

Bibliography

Dippie, Brian W. "Charles M. Russell and Guy Weadick: A Match Made in Stampede Heaven." Alberta History 60, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 15-23.

Finkel, Alvin, Sarah Carter, and Peter Fortna. The West and Beyond New Perspectives on an Imagined Region. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2014.

Foran, Max. "A Lapse in Historical Memory: Guy Weadick and the Calgary Stampede." American Review of Canadian Studies 39, no. 3 (2009): 253-70.

Hamblin, Jennifer. "Queen of the Stampede: 1946-1966." Alberta History 60, no. 3 (Summer 2012): 33-43.

Kelm, Mary-Ellen. "Manly Contests: Rodeo Masculinities at the Calgary Stampede." The Canadian Historical Review 90, no. 4 (2009): 711-51.

Kossuth, Robert. "Busting Broncos and Breaking New Ground: Reassessing the Legacies of Canadian Cowboys John Ware and Tom Three Persons." Great Plains Quarterly 38, no. 1 (2018): 53-75.