Walking Tour

Canadian Dream to a Canadian Nightmare

First World War Internment in Banff

Andrew Farris

Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund

The story of the Banff internment camp is part of a dark chapter in Canadian history. From 1915 to 1917, hundreds of men were brought here to do forced labour in appalling conditions. They were housed at a seasonal camp at Castle Mountain from roughly May to November, and then spent winters and springs at a camp here at the Cave & Basin. They were forced to labour at gunpoint constructing roads, bridges, and amenities like the Ice Palace and toboggan slide in Banff itself.

The men were forced to work in old and torn clothing in almost all conditions, including in temperatures of -40°C (-40°F). They were shot at if they tried to escape. If they refused to work the guards beat them, bayoneted them, threw them into tiny solitary confinement cells for weeks, and reduced their diet to bread and water.

The men interned here were not enemy spies or saboteurs. They had committed no crimes. Almost all of them were immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire (primarily from the empire's ethnic-Ukrainian provinces) who had been designated "enemy aliens" at the outbreak of the First World War. For the most part, they were interned to keep them from competing with Canadian-born workers for jobs.

As the historian Bill Waiser writes in Park Prisoners:

"It is doubtful whether the Canadian public knew, let alone cared, what was going on at Banff and other internment facilities across the country."1

Tour Route

In this tour, which travels around the former camp site at Cave & Basin, we will learn the stories of these men and hear about the trials they endured. We will also explore the stories of the men who guarded them and try to understand how such cruelty could be allowed to happen.

The Banff camp is perhaps the best documented of the 24 internment camps that were set up across Canada during the First World War. The story of these camps was almost totally forgotten after the war, but in recent decades, awareness of this history has grown. Through the tireless efforts of researchers, the internees' descendants, and organizations like the Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund and the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, we now have a wealth of information about this place.

Readers should be warned that the story is sometimes shocking.

Today, Banff National Park is a playground for millions of people every year. It is important to understand and reflect upon the forgotten injustices that contributed to our enjoyment of the park today.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. The Internees

ca. 1916

This group portrait of internees and guards was taken in front of the Cave & Basin site during the First World War. The spectacular vista of Cascade Mountain does not appear to have impressed these exhausted men, who wear blank and bemused expressions. Their clothes are tattered, and at centre, two guards stand at attention with bayonets fixed.

In most images taken of the guards at this camp, their bayonets are fixed. These weapons weren't just for self-defence—they were tools. The guards jabbed the internees with them whenever they showed resistance to labouring in appalling and inhumane conditions.

Most of the internees in this photo were likely Ukrainian, which was the predominant nationality in the camp. An American diplomat reporting on the condition of the approximately 400 internees said that in addition to Ukrainians there were "Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Russians, Serbs, Romanians, Croatians and Bulgarians." There were also two German prisoners.1

These men had been welcomed into Canada as immigrants years before. How then did they find themselves in a frigid and remote forced labour camp?

As we will see, the journey from Canadian dream to Canadian nightmare took a few steps.

* * *

Some of those immigrants were reservists in the German and Austrian armed forces and heeded the call of their Fatherlands to return home and fight. Almost immediately, the government began arresting and interning reservists who were caught at the border. This seemed like a reasonable step to save the shedding of Allied blood.

Then, reports of spies and sabotage started to roll in. Canada was swept by hysteria. Every fire, assault, or accident was blamed on enemy saboteurs. The sensationalist press had spent the previous decades fomenting racism and xenophobia against these same central and eastern European immigrants, so the Canadian public was well primed to believe that immigrants were now trying to blow up trains or help prepare the way for the Kaiser's armies.

The Canadian government quickly concluded that there was no vast network of spies or sleeper agents in the country. An overwhelming preponderance of police reports indicated that most German and Austro-Hungarian immigrants were loyal to Canada or at the least felt that the war was none of their business. Nevertheless, the government used the sweeping and draconian War Measures Act, passed on August 22, 1914, to redesignate immigrants born in enemy countries as "enemy aliens." They then began interning any "enemy alien" who was suspected of disloyalty. It was left up to local authorities to decide who to arrest, which meant that across the country, people started denouncing as traitors any neighbour they didn't like or business competitor with a suspiciously foreign-sounding name.

Records show that most government officials had little antipathy towards German and Austro-Hungarian immigrants. Yet they wanted to minimize risk, and in their calculations, the risk of looking soft on enemy aliens was greater than that of stripping civil liberties from immigrants.

As the government erected a nationwide network of internment camps, many businesses, acting on public pressure or private conviction, began firing enemy aliens. In October of 1914, the Victoria Colonist estimated that by winter, as many as 100,000 enemy aliens would be destitute and living on the streets of Canadian cities.3 Mass starvation was a real possibility. Many immigrants asked to go to the neutral United States to look for work, but they were not permitted to leave the country, lest they join an enemy army.

This left the difficult question of what to do with these people. The government answered by criminalizing homelessness among enemy aliens and moving people into internment camps. Justice Minister Arthur Meighen would later put it succinctly: "We interned these people because we felt that, saying to them 'You shall not leave the country,' we were not entitled to say, 'You shall starve within the country.'"4

The great majority of those who were interned were neither reservists nor suspected spies, but destitute men, primarily from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most were from nationalities that chafed under Austrian rule and had no loyalty to Canada's enemies—the majority of the 8,579 internees were ethnic-Ukrainian. By this stage, however, loyalty was beside the point.

As the camps filled, the press fanned public outrage by claiming that these supposed "traitors" were reposing in pampered luxury in what they termed 'summer camps.' "Who would not be an alien enemy?" sneered the Red Deer News.5 The historian Bill Waiser explained the result:

"The Canadian public was not simply content to see enemy aliens interned; they had to be put to work and not allowed to laze about at government expense while Canadian soldiers lost their lives on the battlefields of Europe."6

Thus, the government decided to save money by putting these immigrants to work. As the Interior Minister said, "it would be better for the men to be doing some work rather than eating their heads off."7

But what work would these internees do?

James B. Harkin, commissioner of the Dominion Parks Branch, had some ideas.

2. Harkin's Parks

ca. 1916

In this image, internees march into the Cave & Basin carrying logs, presumably firewood. A guard with a rifle slung over his shoulder looks at the camera while the faces of the internees are bathed in shadow. This was the second camp in Banff to which they had been dispatched. They had previously been at a tent camp near Castle Mountain, some 60 km to the west, where they had worked to build the road to Lake Louise. In the winters, they came here, to a hastily established camp at the Cave & Basin where they were set to work on various projects around Banff's townsite.

The lobbying of James B. Harkin, the commissioner of the Dominion Parks Branch (the forerunner to Parks Canada) was partially responsible for the government's decision to use internee labour here. He was the first to hold the position of commissioner, and is now commonly remembered as the Father of Canada's national park system. Harkin was a visionary who believed in the therapeutic power of nature to heal souls. He had vast ambitions to develop parks like Banff and open them to all Canadians. Yet when the war broke out, his department's budget was cut in half and his grand plans were stymied.1 When he heard that internees were being used as labourers at Kapuskasing in Ontario and at Spirit Lake in Quebec, he persuaded the government to have internees brought to Banff and other national parks to help realize his ambitions.

* * *

Harkin had a philosophy that tied together conservationism, morality, and economics. He felt that access to parks would rejuvenate what he called the "play spirit" in Canadians by getting them into the outdoors and making them better, happier, and more moral people.2 He also advocated for the parks on economic grounds. He submitted a formula to his superiors that argued that an acre of "Canadian scenery" was worth $13.88, whereas an acre of Canadian wheat fields was worth only $4.91. Furthermore, the scenery was permanent.3

At the outbreak of war, Harkin bemoaned the catastrophic 50% budget cut to his fledgling department, but he also saw opportunity. He wrote admiringly of the "virile and efficient manhood so visible in Canadian military training camps" and argued that after the war, the parks would provide soldiers with a soothing balm to ease their traumas.4

Harkin also had modern ideas. By his time, cars had been invented, and they were becoming much more widely available. He argued that "the twentieth century [was] to be the century of the automobile as the nineteenth century was the century of railway."6 If roads were built, far more Canadians would be able to drive to the parks, and this would be better both patriotically and economically.

Harkin therefore convinced the government that internee labour could be invaluable in building a road to Lake Laggan (now Lake Louise). It could also help with the construction of all manner of other amenities across the Banff townsite. Ultimately, internee labour would also be used at Jasper, Yoho, and Mount Revelstoke National Parks.

As Harkin would later write:

"It was felt that it was not good for the prisoners to live for months in a state of idleness; that it would be advantageous for them to have work to do and that, having to maintain them in any case, it would be good business for the Government to secure with such labour the construction of roads and other public works in the park."7

One of Harkin's political patrons, Alberta MP and future prime minister R.B. Bennett, threw critical support behind the internee labour plan on the condition that the prisoners were kept isolated from the public and not "coddled or indulged in any way."8

He didn't have much to worry about.

3. Off to a Bad Start

ca. 1916

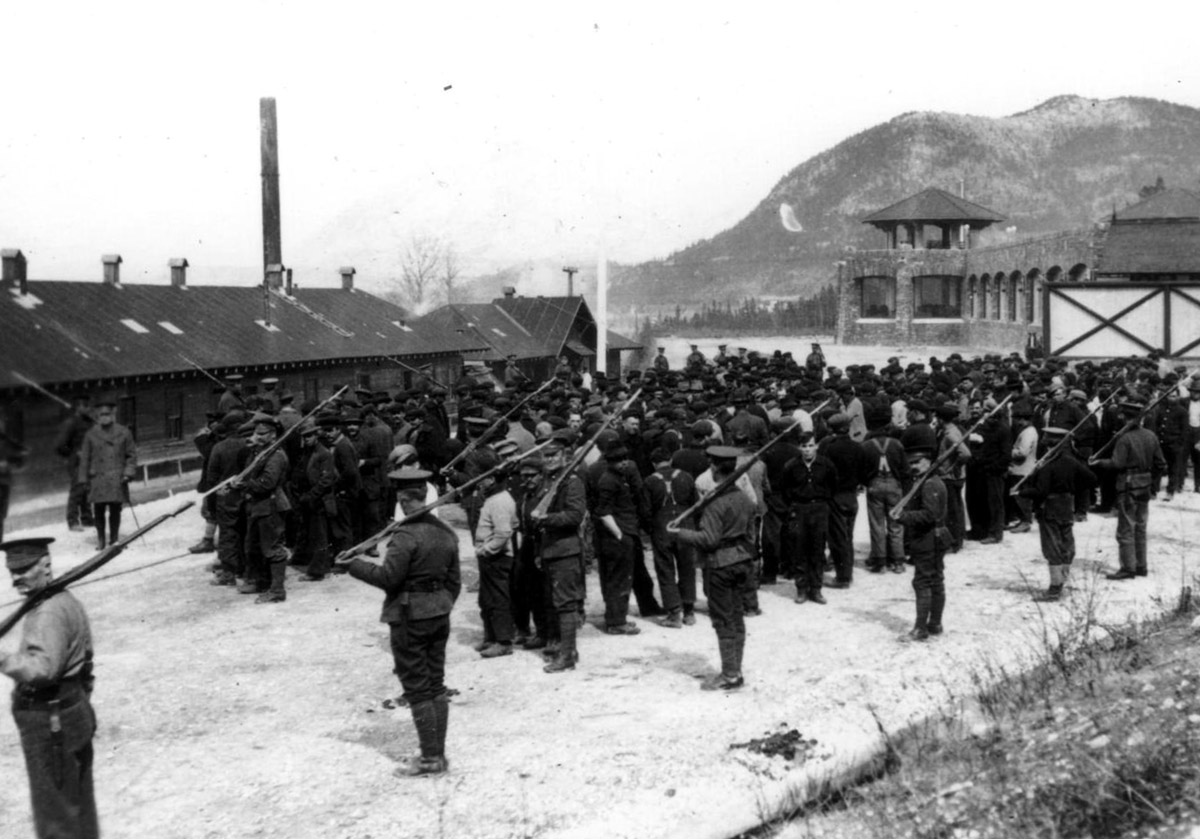

In this image, prisoners under guard are gathered on the parade ground during a fire drill. Fire drills were a frequent occurrence, if the camp's official diary is anything to go by. That remarkable document has been published as a book called In The Shadow of the Rockies, edited and annotated by Bohdan S. Kordan and Peter Melnycky. The diary gives us insight into life in this camp, describing the ill-disciplined guards, poor provisioning, and frequent escapes.

* * *

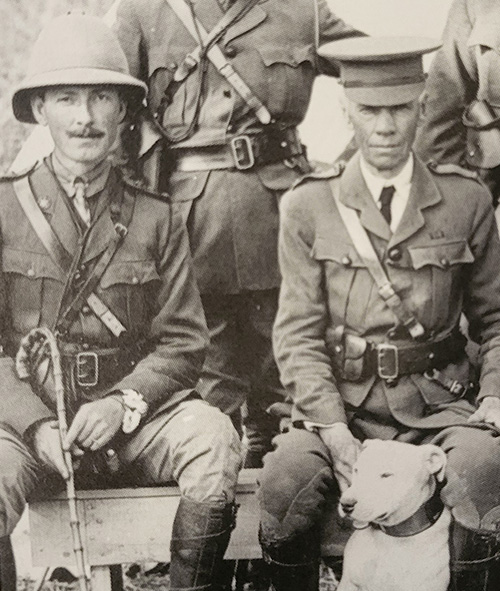

The internees were under the supervision of a body of guards headed by Captain Peter Spence. Spence was a wiry and prim man of military bearing, sporting a neatly-trimmed moustache and pith helmet.

As he oversaw the camp's setup, Spence complained of endless rain, a camp that had been "very poorly built" by "government teamsters," incompetent railwaymen who dropped food and supplies at the wrong spot, and rotting tents supplied by the Hudson's Bay Company. The site was so poorly chosen that it had to be dismantled and relocated a few kilometres down the road to a patch of forest that had to be cleared.1 It was an inauspicious beginning.

Major Duncan Stuart arrived to take command and commended the "unremitting zeal and industry" of the guards (neglecting to credit the internees who were actually doing all of the industry). He requested more prisoners as it would give the guards the "feeling that we are doing something the more worthwhile."2

He also requested twice as many guards as the 35 he had since "if [the prisoners] wanted to escape I consider the men we have totally inadequate."3 Escapes were going to be a major problem at the camp, and would soon help cost Stuart his job.

For the rest of 1915, the prisoners succeeded in extending the road bed about 6.5 kilometres towards Lake Louise. This was not a fast enough pace for Harkin and the Parks Branch, who complained bitterly.

The arrangement between Dominion Parks and the military was bound to cause conflict. The Parks Branch paid the prisoners a miserly wage (25 cents a day, 1/12 the going rate for labour), and provided foremen who directed the work.4 Harkin wanted the most bang for his buck, which meant making the prisoners work as fast as possible for as long as possible.

The military supplied the guards, and their overwhelming imperative was to prevent escape.

In practice, these goals were at odds. If work was pushed too hard, the misery of the prisoners was exacerbated and the guards spread too thin. As a result, prisoners would find opportunities to escape or refuse to work. If security was tightened or guards sent out to search for escapees, the work would slow to a crawl. The harsh military discipline and punishments imposed on the prisoners also interfered with the work. On August 17, a work gang returned to camp too early, and the commandant ordered that they be denied dinner. In an early act of defiance and solidarity amongst the internees, they all went on a hunger strike in protest. The next day, an internee collapsed from weakness. The frustrated Parks foreman "refused to continue working the prisoners in their present condition" and demanded that they be given food. Major Stuart relented.5

It's hardly surprising that the first escape was just over a week after Duncan took command. The diary entry for July 21, 1915 reads: "Prisoner of war No. 14 J. Jelinick from No. 1 company escaped while working beside motor road. Patrols sent out east and west and all neighbouring police notified."6

This escape wasn't to be the last.

4. Building Banff

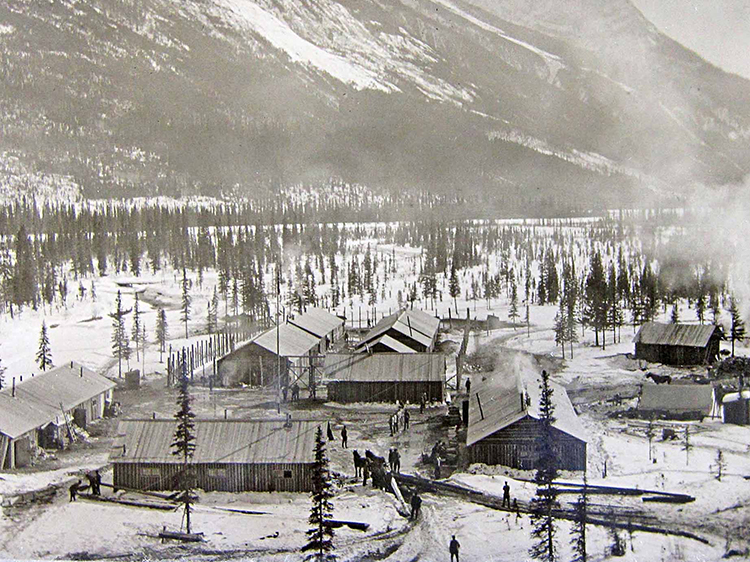

ca. 1916

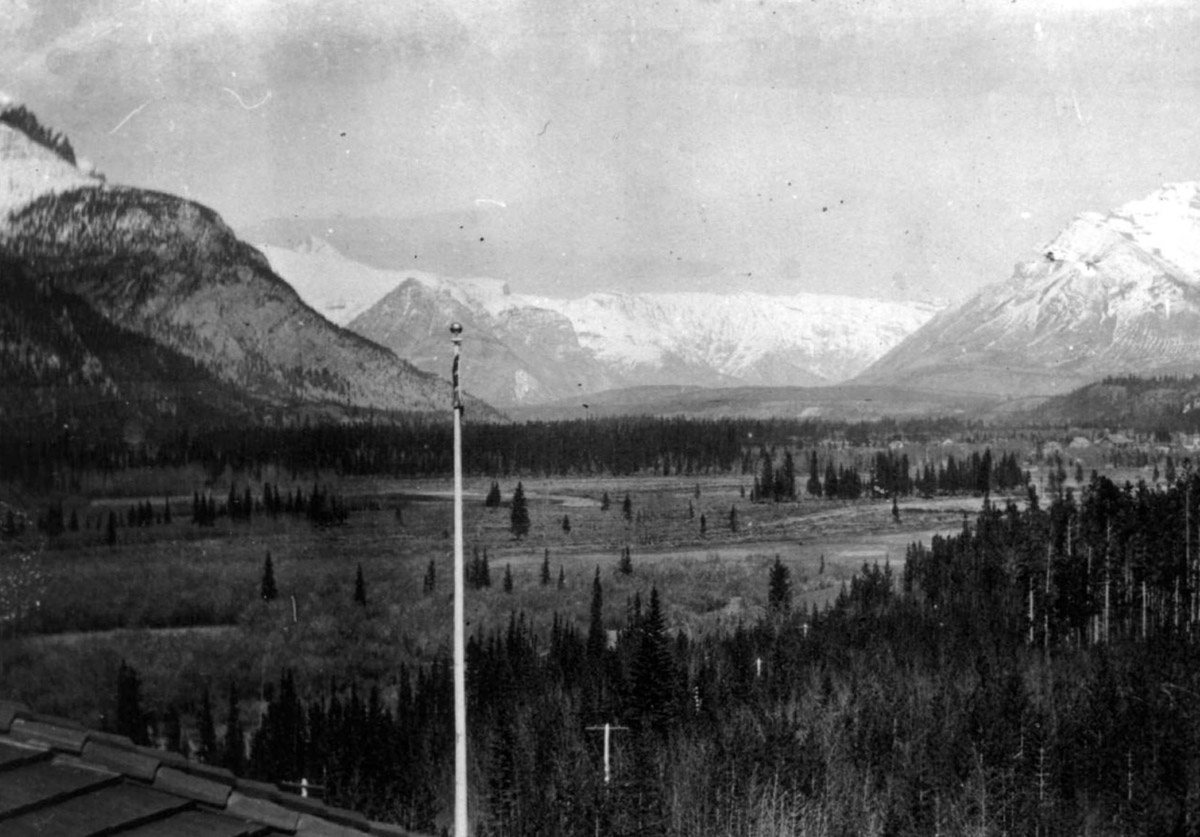

In this image, the winter camp at the Cave & Basin is seen from the balcony atop the Cave & Basin building, which is now a National Historic Site. It is home to the famous sulphur springs that have been sacred to the Indigenous peoples of this region since time immemorial, and which have attracted millions of tourists since the 19th century.

As winter bore down on the tent camp at Castle Mountain, the camp authorities decided to move the internees to somewhat more permanent lodgings here. The building you see at right in the historic photo was used to house construction workers before the war, and it now became the guards' quarters. In the background of the image, you can see the prisoners' bunkhouses, set on the side of a steep slope—an odd choice that indicated how little planning had gone into this site. The bunkhouses were rudimentary, poorly-heated, and overcrowded.

While in their winter quarters, the prisoners were still made to work around the Banff townsite on whatever tasks the Parks Branch could devise for them. Conditions for the 400 internees (200 more had arrived from the Brandon internment camp) rapidly deteriorated throughout 1915 and 1916.

The internee Nick Oliynick wrote to his wife: "As you know there are men running away from here every day because the conditions here are very poor, so that we cannot go on much longer. We are not getting enough to eat. We are hungry as dogs. They are sending us to work, as they don’t believe us, and we are very weak."1

* * *

Once they were settled here, internees began a new winter routine which involved marching out in deep snow to work at various odd jobs around town. If you've spent any time in Banff, you've almost certainly been somewhere where they worked.

As the historian Bohdan S. Kordan writes, aside from clearing land for the new St. Julien subdivision and draining the marsh that is today the Banff Recreation Grounds, they had many other tasks:

"Brushing the buffalo paddocks, building the retaining rock wall at Bow Falls, and repairing sidewalks and streets in town. They were also put to work on a variety of projects in and around Banff for the amusement and leisure of the locals and visitors alike: building a ski run and toboggan glide, an ice palace for the winter carnival, and hiking trails for the Alpine Club of Canada; clearing land for horse pastures, tennis courts, and a shooting range; extending the golf links and constructing an access road to the golf course at the Banff Springs Hotel."2

Their main task, however, remained road building. They built the roads to the Middle Springs and Upper Hot Springs, straightened out the corkscrews on the road on Tunnel Mountain, and spent enormous energy building a bridge over the Spray River.

For their part, the people of Banff were thrilled to have this forced workforce improving their community.

5. The Nightmare

ca. 1916

This photo of internees having a snowball fight with guards on the other side of the wire shows a rare moment of levity in the camp. It's a curious scene that belies the many reports we have of the miseries inflicted on the internees.

Some prisoners who refused to work were chained to trees. One prisoner who said he was too sick to work was struck with the butt of a guard's rifle and called a "son of a bitch." Argumentative prisoners had bayonets jabbed into their bodies. Prisoners who didn't get out of their bunkhouses fast enough were driven out at gunpoint. A guard fired his rifle at a man who was taking too long in the latrine. The most common punishment for refusing to work was being shackled and thrown in a solitary confinement cell (the "hoosegow") for up to 14 days on a diet of bread and water.1 2

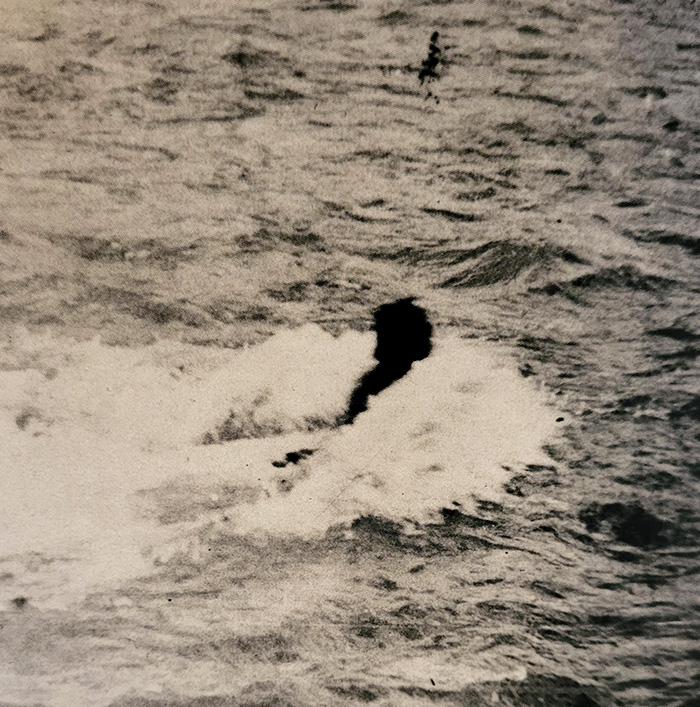

One creative and cruel punishment used at the camp was to tie a rope to a man and throw him into the frigid and fast-flowing Spray River. There's even a picture of it, originally captioned "Immediate and Effective Punishment", though Bohdan S. Kordan has noted it is unclear whether the image shows an internee being given this treatment, or a guard who has committed a disciplinary violation.

All of this was well-documented and reported up the chain of command.

Canada's official legal position was to claim that all internee labour was voluntary. Forcing civilian internees to work violated international law and made Canada an outlier among the First World War's combatant nations. Germany, Britain, Austria-Hungary, and France did not inflict this upon their "enemy alien" civilians.3 When the United States joined the war in 1917, they specifically studied Canadian practices to avoid repeating them.4

* * *

Publicly, Otter maintained the treatment of internees was beyond reproach. In his final report to parliament on internment operations at the end of the war, he wrote: "Apart from the natural irritation consequent upon a deprivation of liberty, the general disposition of prisoners was philosophical acceptance of the situation, the policy adopted being that of humane treatment throughout." He asserted that "little complaint can be made," about the treatment of internees.6

General Otter's correspondence shows that his private views were quite different.

Wasyl Tkachuk was an internee who successfully escaped from Banff on March 8, 1916. He detailed his experiences in a letter to the Robochyi Narod, a Winnipeg-based Ukrainian-language newspaper. (Later in the war, the Robochyi Narod was banned along with many other "enemy alien language" publications).

Tkachuk described being "mercilessly driven on by the English guards". He told the story of one internee who refused to work and was therefore "chained by his arms and legs and placed in the cell for fourteen days on bread and water with only one blanket, emerging from confinement completely crippled by rheumatism."7

A neutral American consul representing the interests of Germany and Austria-Hungary visited the Castle Mountain Camp in the fall of 1915 and heard many complaints of abuse and appalling conditions. For example, two prisoners named Bilk and Botha told him that they were threatened with being shot for refusing to work. A guard pistol-whipped Botha and then put his revolver to the man's temple.

The consul sought clarification from General Otter, who wrote back:

"The various complaints made to you by the prisoners as to the rough conduct of the guards, I fear, is not altogether without reason, a fact much to be regretted and, I am sorry to say, by no means an uncommon occurrence at other Stations."8

When another American consul, Gebhard Willrich, inspected the Spirit Lake camp in Quebec, the camp commandant realized that he'd made a mistake in allowing the consul to speak with the internees alone and take letters from them. It was clear that Willrich was going to make an unfavourable report. The commandant frantically notified Otter to see if the consul could be stopped by police and have his materials confiscated.

Fearing another international embarrassment caused by leaked details of Canada's abuse of civilian immigrants, Otter went directly to Prime Minister Robert Borden. Borden had his officials complain to the Americans that Willrich's German-sounding name was evidence that he had pro-German sympathies and was therefore not a neutral arbiter. The Americans fired Consul Willrich.9

Otter was privately embarrassed by some of the allegations. In that aforementioned Chicago Tribune report, it was claimed that "strappado" was used in the Lethbridge camp. Strappado is a kind of torture during which a person's hands are tied behind their back and they are suspended in the air with their feet barely touching the ground.

Otter privately conceded that this form of torture was happening in the camp, and wrote of the camp's commandant that "a repetition must not occur… if a more close supervision cannot be exercised over… his command… the good name of Canada [will be] brought to a level with the Huns." 10

Preservation of Canada's 'good name' was a major concern since reports like this were causing Canada (and by extension Britain) international embarrassment, as both sides in the war sought to portray their enemies as barbaric. These ongoing reports were a propaganda coup for Germany, who sought to draw attention away from the widespread reports of their own mistreatment of Allied prisoners of war they'd captured in battle. They focused their outrage on the forced labour of German civilians, and they threatened to reciprocate this treatment on British Empire civilians in their own lands. The British were furious that excesses committed against German civilians in Canadian camps could lead to the mistreatment of their citizens, and urged Canada to rein in the abuses.11

Fortunately for the Canadian government, Austria-Hungary showed almost no interest in the welfare of their citizens in internment camps, especially those from one of the dozen or so non-German ethnic minorities that constituted the empire. It just so happened the vast majority of those in the camps were destitute Ukrainian men who had immigrated from the Austrian Empire. Canada responded by only sending these men to the remote forced labour camps, while German and ethnic-German Austrians were kept in more traditional prisoner of war camps at places like Fort Henry and the Halifax Citadel. It worked because Canada's mistreatment of civilian internees only mattered if the victims had an advocate. The Ukrainians and other subject nationalities of the Austro-Hungarian Empire did not have one.

6. Winter

ca. 1916

In this picture, guards exchange snowballs with prisoners within the barbed wire enclosure. The winter conditions were brutal for the internees, and they were still forced to work in them.

During the winter, the camp diary recorded the temperature each day and whether or not internees were sent out to work. It appears that the prisoners were excused from work only on Sundays and when it was colder than -30°C, or -22°F (the original diary entries were recorded in Fahrenheit and we have here also converted them to Celsius). The entries for January 1917 show that it was never warmer than -5°C (23°F).1

When they were sent out, the internees were expected to work eight hours without regular breaks in addition to the march to and from the work sites. These marches, through snow drifts and freezing wind, could be up to 10 km each way. Their lunches were frozen and their feet frostbitten. Their tattered clothing was grossly inadequate.

On the many days when it was colder than -30°C (-22°F), the internees were still forced to work around the camp in one hour shifts. They spent the rest of their time in the poorly-heated bunkhouses. There was no respite for them.

* * *

When the winter clothing finally arrived some time later, one historian notes it "had more to do with the upcoming inspection than Stuart's pleading."3

The next winter, it happened again. The diary records that most shipments of winter clothing weren't distributed until January 1917, and many of the internees had once again been working for months in subzero temperatures in summer clothes.4

Reading between the lines in the bland, terse language of the camp diary, one can scarcely imagine what these days were actually like.

January 12th: Fine, very cold, windy at night and milder. Temperature, Max. -18°C (0°F), Min. -32°C (-26°F). Too cold for park work [in morning]. At 1:00 p.m. 93 prisoners of war were sent out on park work.

January 13th: Some gangs refused to work.

January 16th: Very cold, clear, fine. Prisoner of war No. 582 injured himself by being hit in the eye by a piece of stone from a rock he was breaking.

January 22: 10 prisoners of war [locked] up having lost or destroyed their rubbers, and 3 for malingering.

January 24: 155 prisoners of war went out on park work, 2 returned as malingerers and placed in Guard Room. Prisoner of war No. 439 returned to camp at 10:35am being injured at Ice Palace by piece of ice falling on his foot… reported bone broken.

January 31: Fine, cloudy, extremely cold. Temperature Max -32°C (-25°F) and Min -42°C (-44°F). In afternoon 20 prisoners of war escorted by 25 troops worked at toboggan slide. Extremely cold with raw east wind.

February 1: Fine, cloudy, extremely cold. Temperature Max -20°C (-4°F) and Min -46°C (-51°F)… 24 [internees sent to] Ice Palace and 40 for toboggan slide.5

There is something disturbing about the frivolousness of starving, frozen, poorly clothed men working at gunpoint in -30°C (-22°F) weather to build an ice castle and toboggan slide.

7. The Guards

ca. 1916

In this picture, a guard stands over an internee as he is forced to pick up a boulder. The photo's original caption reads "A Stubborn Prisoner." It's doubtful that the guard in this picture had this job in mind when he was enlisting to fight in the First World War.

Most of the camp guards were drawn from the 103rd Regiment Calgary Rifles. Others were directly enlisted in Banff and given a uniform and a gun before being put on duty with virtually no training. Ironically, many of the guards were unemployed working class immigrants, just like the men who they were guarding. In most cases, both guards and internees had come to Canada from Europe. The only difference between them was the country from which they'd come.

This internment camp was in many ways a supercharged, real life Stanford Prison Experiment. In that famous 1971 psychology study, volunteer students were randomly assigned the role of prisoner or guard and then put in a simulated prison. Researchers were shocked to find that within days, the "guards" began to brutally abuse the "prisoners", both physically and mentally. A number of the "prisoners" had mental breakdowns. The experiment was terminated after only six days, and it remains widely regarded as the most unethical study in the history of psychology.1 The Banff internment camp was open for two years.

The conditions in which the guards lived were miserable too and contributed to their despondency and brutality. There were not enough guards in the camp, so each man was on duty for 85 hours a week and was often required to pull 24 hour shifts.2 They were so poorly trained that they had more success accidentally shooting each other than they did shooting the escaping prisoners. At least one of them was just 16-years-old.3 Drunkenness on duty was endemic and resulted in many court martials. If prisoners escaped under a guard's watch—which happened often—the guard was subjected to a humiliating board of enquiry and severely disciplined if found negligent.

* * *

Just over a year later, Lomax lay dead on a shell-pocked battlefield in Europe.5

Private J. Elliot's story demonstrates the razor thin line that separated those with guns from the men they guarded. Elliot sent a letter to the commandant asking to be discharged from his duties so that he could support his destitute, widowed mother. "I find it almost impossible to make both ends meet," he said.

His request was denied. Spence wrote that the private "was apparently absolutely destitute when he was taken on to this detachment last December," and that therefore, his release would not help his mother.6

Had Elliot been born in Austria-Hungary, his destitution would have been grounds for internment. A month later, he was accused of allowing two prisoners to escape and court martialled.

Internee John Dykun served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force for a full eight months before someone realized that he had been born in an enemy country. He was denounced as a spy and interned. While being forced to work at Castle Mountain, he and two other men made a dash for the forest. The guards opened fire. One man, named Konowalczuk, was hit twice in the chest and collapsed.

Konowalczuk survived his wounds (the local paper, the Crag and Canyon, crowed that he'd received a "deserved lesson"), but Dykun and the other escapee quickly surrendered to the guards. They had not originally thought that the guards were actually shooting to kill. Dykun can hardly be blamed for believing this, as he had been wearing the same uniform as the guards just weeks before.7

There were dozens of instances during which guards shot at escaping prisoners, yet Konowalczuk was the only one to ever get shot. This could have been due to the guards' natural reluctance to kill, but it might also have been because they were genuinely bad shots. Most had almost no training. Commandant Spence was irritated by the prisoners' belief that the guards weren't shooting to kill. To intimidate the internees and discourage more escapes, he had his men participate in loudly trumpeted marksmanship competitions.

The treatment of the guards by their officers also contributed to abysmal morale.

Private J.S. Grindlay took ill with influenza on February 4, 1916. The camp's chief medical officer refused to send him to Banff's hospital and instead confined him to his bunk for a week as his condition deteriorated. This was far more than he often did for sick internees, who he would sometimes send back to work with the note "He is just tired of work. Nothing wrong."8 Nevertheless, after a week, Private Grindlay was delirious with fever and "speaking of the fourth dimension." The medical officer relented and sent him to the hospital in an open horse cart in temperatures that the diary indicates were probably around -20°C. Grindlay died the next day. The other guards blamed his death on the medical officer's neglect and were reportedly greatly distressed.9

The strain of the job was too much for Private A.H. Brearly. He walked into a Banff recruiting station on December 15, 1915, and within two weeks, was doing 24-hour guard duty shifts at the camp. Like Grindlay, he fell ill with influenza, but unlike Grindlay, he was sent to the hospital before it was too late. However, his case was serious enough for the Banff doctors to recommend that he be sent to Calgary for proper care. Commandant Spence denied the request, saying that he couldn't spare a single guard. Brearly returned to duty without fully recovering and remained sickly thereafter. On May 20, he walked into the forest behind his Banff home and cut his own throat with a razor.10

Trapped as they were in this horrible situation, many guards turned to alcohol, which also contributed to the frequent violence they inflicted upon the internees. Commandant Spence banned his guards from going into Banff's bars and liquor stores, but these orders were ignored.

8. Escape

ca. 1916

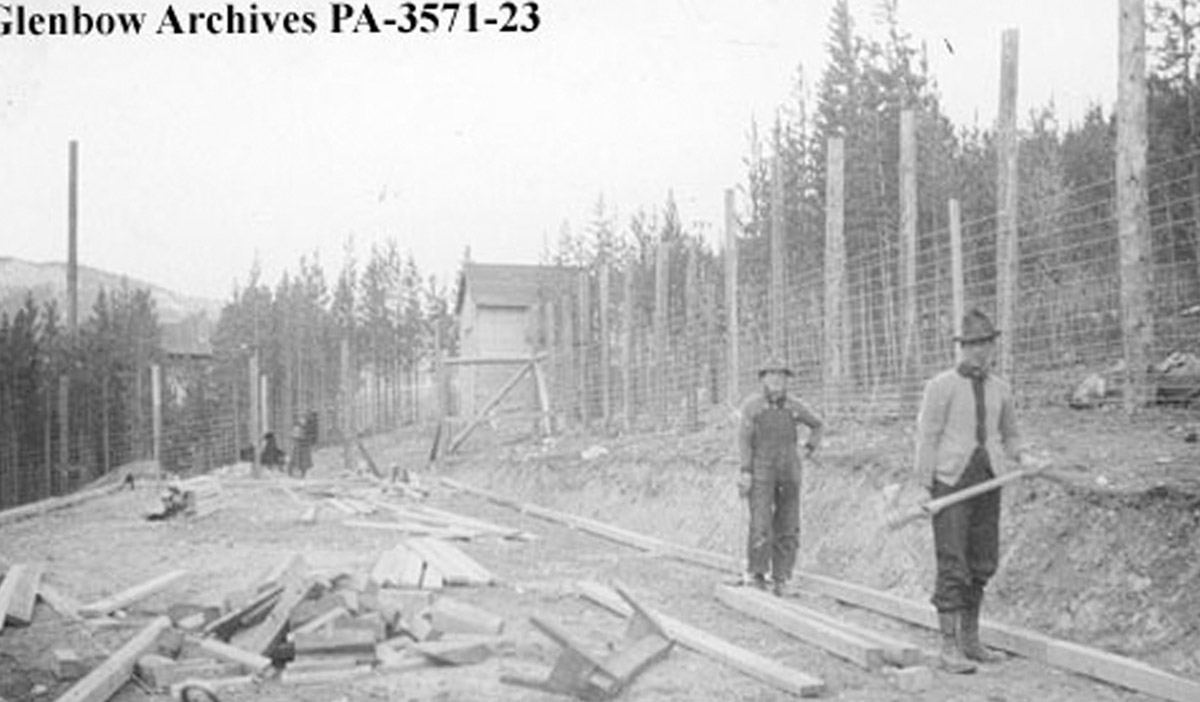

In this photo, two internees work to erect their own prison at the Cave & Basin. Barbed wire enclosures like the ones these prisoners built were effective at preventing escapes. Yet when a handful of exhausted guards are tasked with shepherding prisoners from worksite to worksite and watching over them for long, tedious hours as they labour at the edge of a vast forest, things become more complicated.

Escapes were a constant occurrence throughout the camp's two year existence, and they began right away. There were eight in just one week in August of 1915.1 Escapes couldn't be concealed from the public, and they were extremely damaging to the reputations of the camp's officers. Enormous effort was therefore made to track down escapees, and the guards were strongly warned to prevent them from happening.

For the internees, escape was a dicey proposition full of great risk. They could be shot, as happened to Konowalczuk, and if they were recaptured, they faced many days of solitary confinement and near-starvation. If they got away, they had few settlements to which they could run, and hiding in the woods could mean death from exposure.

Nevertheless, many prisoners felt that it was a worthwhile gamble. In the first 10 months of the camp's operation, 61 men escaped, and only 22 were recaptured.2

* * *

John had been living in Canada for eight years when he was interned at Banff. On February 4, his father Jacob wrote a letter to the authorities asking why this had happened and saying "I do not think that Canada would take their own people and put them in an Internment Camp. I am naturalized as a citizen of the Dominion of Canada. Please let him go."

Upon investigation, it did indeed seem that there wasn't any real reason for John Kondro to be there. As John's father was a naturalized citizen, the camp authorities weren't sure if that meant that Kondro—who had lived in Canada since the age of nine—counted as one as well. Commandant Spence was asked to report how Kondro had behaved. Evidently, the decision to release him was more contingent on his good behaviour as a prisoner than it was on the legality of his imprisonment. Spence reported that Kondro was a good prisoner: quiet and usually obedient. He had been put in solitary confinement "only once for several days for refusing to go to work."3

Kondro's file was sent to Ottawa and circulated amongst various departments for comment. Unfortunately, decisions to free people who had been wrongly interned were not a priority. Months passed.

Kondro grew tired of waiting. On April 10, he escaped with six other prisoners. The others were recaptured, but Kondro was never seen again. He died somewhere in Banff National Park.

The best hope for escaping prisoners was to hop on a train or find some compatriots who could shelter them. On one occasion, four escaped prisoners made it to the Georgetown Collieries, a coal mine east of Banff, and were taken in by some other "enemy aliens" who worked there. They were tracked down and caught. As for their hosts, the Crag and Canyon remarked "Four fellow Austrians, who were enacting the part of the good Samaritan and harbouring the runaways were also gathered in and added to the menagerie of the Internment camp."4

For some, death was the only means of escape. George Luka Budak was Romanian, and therefore on the Allied side, yet he was called an Austrian liar and interned anyway. In one of the camp buildings in December of 1916, he found a razor and slit his own throat.5

9. The Officers

ca. 1916

In this image, guards drill with their rifles in front of the guards' quarters on the main parade ground. The entirety of the Banff camp's existence was plagued by poor leadership, managerial incompetence, and official neglect.

The Crag and Canyon was thrilled to have enemy aliens doing work around the park, but even they were concerned about the camp's running: "Conditions are just not what they should be at the camp."1

These problems characterized most of the internment camps that were set up across Canada, although the remote forced labour camps in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec were particularly bad. Banff was especially bad, and the terrible leadership contributed enormously to the misery of the prisoners.

Some abuses resulted from the desire of the camp's officers to preserve their reputations, and many went on to illustrious post-war careers. The internees who they had traumatized and abused, however, were forever cursed with mental and physical scars, and most lived in fear of Canadian society turning on them again.

We should also understand, however, that the choices these officers made were in the extraordinary circumstances of a cataclysmic world war and in the context of prevailing political and economic systems that placed almost no value on the well-being of "enemy aliens".

* * *

Stuart was fired at the end of 1915. Brigadier General Ernest Cruikshank, commander of Alberta's Military District, wrote that Stuart "complained that he had been treated unfairly."

Nevertheless, after the war Stuart became a "lawyer and community leader" in Calgary and a respected expert in land and soil management. He also went on to found the city's Earl Grey Golf Course.4

His subordinate, Captain Peter Spence, was promoted to Major and given Stuart's job. His orders from Cruikshank were to prevent escapes, improve his soldiers' discipline, and stop their abusive behaviour. He was also told to make the internees work much faster, as Harkin was loudly complaining about the slow pace of progress.

Spence was a harsh disciplinarian—he once wanted a sentry who had been caught sleeping to be given a lengthy prison sentence "as an example to the other soldiers."5 However, his harsh discipline likely further damaged morale. Shortly after he took over, Private Grindlay died in hospital and Private Brearly committed suicide.

The poor discipline, drunkenness on duty, and prisoner abuses continued unabated. The camp diary makes it sound as if Commandant Spence spent much of his time going to and from the military court in Calgary to testify in the court martials of his own men.

Spence remained commandant until the camp closed in August of 1917. After the war, he became a journalist at the Calgary Herald and the publisher of the Vancouver Province.6

Spence's superior, Brigadier General Cruikshank, demanded that Spence put a stop to the abuses of the internees. Yet one incident annotated in the camp diary by Kordan and Melnycky demonstrates how the brigadier general prioritized his own career over the lives of the internees.

After one of his inspections, Cruikshank reported to Ottawa that the camp was extremely overcrowded. There were four bunkhouses for 420 men. They were poorly heated in a season during which temperatures regularly dropped to -40°C (-40°F). To heat water, the internees in one bunkhouse had to thaw snow in a discarded tin over a tiny cook stove.

To relieve overcrowding, Ottawa ordered the transfer of some internees to another camp. Cruikshank seems to have realized that this might hurt his reputation as an effective administrator, and he retracted his initial report. He claimed that he had been mistaken and that there was in fact room for another 140 prisoners.7

The prisoner transfer was cancelled, and Cruikshank's reputation was preserved. After the war, he was appointed the first Chairman of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada and made a member of the Royal Society of Canada.

As for James B. Harkin, the father of Canada's National Parks, he seems to have felt little compunction that his scheme had turned into a nightmare. The first and primary justification he had originally given for the plan was that it was "advantageous" for the internees.8 Nevertheless, when some internees at the Mount Revelstoke camp went on strike, Harkin complained to General Otter that the commandant wasn't more vigorously coercing them back to work. Ignoring the internees' demands for adequate food or warmer clothes, Harkin instead demanded a commandant who would use harsher measures. Otter fired that commandant.9

After the camps in the national parks were shut down in 1917, Harkin tried unsuccessfully to persuade the government to have the internees replaced by the inmates of the country's jails. During the Great Depression, he oversaw the opening of relief work camps for the unemployed in the parks. Conditions in these were bad enough to help spark the famous On to Ottawa Trek, as thousands of men streamed out of relief camps and rode the rails to the capital to demand that the government treat them like human beings. Harkin retired in 1936, but Japanese internee labour was again used to improve Canada's National Parks during the Second World War.

10. The Chapter Closes

ca. 1910s

To access this viewpoint, you can climb up the stairs at the front of the Cave & Basin building, which lead to the viewing platform.

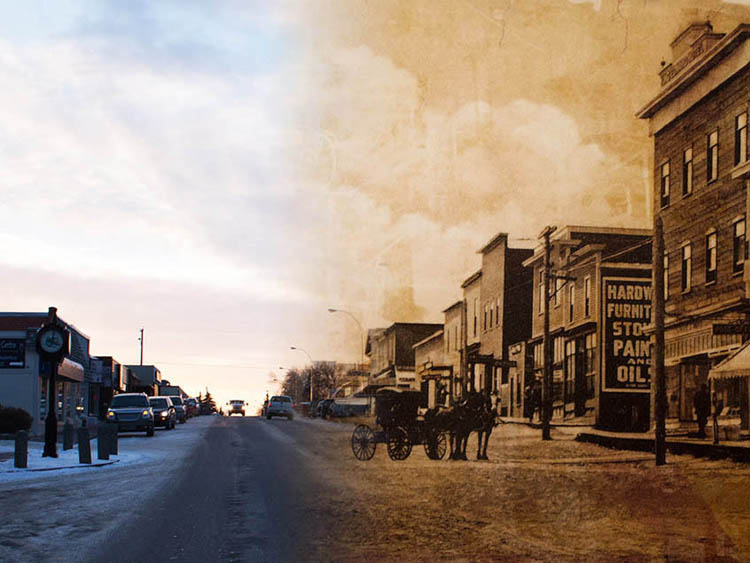

This photo shows a view of the fledgling townsite of Banff, which benefited so much from the forced labour of the men imprisoned here.

The camp slowly began to wind down in the late spring of 1916, and it closed in August of 1917. From the military's point of view, there was simply no more need for it. The main reason that these people had been interned was to keep them from competing with Canadian-born workers for scarce jobs in 1914 and 1915. By 1916, the war's voracious appetite for the lives of men meant that there were now not enough workers left to fill all the jobs. Industry clamoured to have the internees work for them, and the government slowly began paroling internees to work in mines, on the railways, in factories, and on farms.

The Dominion Parks Branch was not pleased with this development. In May of 1917, Banff's superintendent Clarke demanded more internees so that they could finish building the Banff Springs Hotel's golf course. "It is imperative that we get more soon to finish what we have in hand before removal to Castle."1

As Bill Waiser writes in Park Prisoners:

"One must try to fathom the emotions of the patrons of the Banff Springs Hotel as they looked down from on high at the scores of internees working under the threat of bayonet and rifle on the golf course below."2

* * *

There are, however, articles like this one from April 1916:

"A bunch of interns took a fancied exception to the quality of the 'grub' served to them, quit their job and marched back to the corral… It might not be a bad idea to 'gentle' a few of the leaders with a pickaxe handle, or cut down the food supply when they refuse to work."4

Another time, the Crag and Canyon said they'd received reports that the internees' work gangs were catcalling women in Banff. After claiming that "this paper does not countenance brutality," it went on to warn that if the guards didn't "suppress this growing evil… some muscular Canadian… will wade into the gang of foul-mouthed, leering Austrians, and armed with a club or some other persuasive weapon, teach the brutes a lesson."5

The paper reported cheerfully on the progress of works across the townsite, although it neglected to mention who was doing the work. This quote is about the internee-built toboggan slide: "The slide was built this year without the expenditure of a dime, all labour, coal, and water hauling, etc. being donated free."6

The articles in the Crag and Canyon help us to understand how so many Canadians were content to see their government treating people in this way. They simply didn't think much about them. We must also remember that at the time, many thousands of young Canadians were dying horrific deaths in a pointless war in Europe, and the nation was coping with a collective tragedy that is hard for us to comprehend today. Hearts were hardened by the horrific sacrifices. No matter how unfair it was to do so, people held the internees partially responsible for it.

We will end this tour with an excerpt worth quoting at length. The passage is by a reporter for the Crag and Canyon who visited the Castle Mountain internment camp and was treated as an honoured guest.

As you read through this, reflect on everything we've learned about this camp: the abusive guards and careerist officers, the bayonetings and solitary confinements, the back-breaking labour and punishment diets. The misery and the despair.

Then, think about what this writer chose to see.

"Three miles further along the trail, an internment camp, a veritable white city, is reached. The camp is ideally located beneath the shadows of the Castle mountain, laid out with all due attention to the laws of hygiene, and cleanliness is one of the watchwords. Pure water is piped down from a stream up the side of Castle Mountain and every attention is given to the health and well-being of the inmates of the camp, in fact the sick bay at the time of the visit contained not a single inmate. The officers from Commandant major Spence down to the non-coms have a conception of the true meaning of the word hospitality, which they dispense with lavish hands, and a dinner in the officers' mess tent leaves nothing to be desired by the most fastidious epicurean…"

Staying overnight, he continued:

"If there is anything more delightful than listening to the patter of rain drops on a tent roof the writer has yet to find it. And to be awakened in the morning and introduced to a plate of hot buttered toast and a huge cup of steaming coffee with the request or command to partake of it before arising to the acme of hospitality. A substantial breakfast in the officers' mess, followed by the run to Banff in the fresh, cool air of the morning makes one think that this old world is a mighty pleasant place to live in."7

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

- 1. Bill Waiser, *Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada's National Parks,* (Toronto: Fifth House Publishing, 1995), 20.

1. The Internees

1. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, *In the Shadow of the Rockies: Diary of the Castle Mountain Internment Camp 1915-1917,* (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1991) , 66.

2. Desmond Morton. "Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada during the First World War," *Canadian Historical Review,* (Vol. 55 Issue 1, March 1973 pp.32-58), 32.

3. Lubomyr Luciuk, *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920,* (Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001), 71.

4. Luciuk, 71.

5. Waiser, 4.

6. Waiser, 6.

2. Harkin's Parks

1. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 116.

2. Alan MacEachern, *Natural Selections: National Parks in Atlantic Canada, 1935-1970,* (Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001), 31.

3. Leslie Bella, *Parks for Profit*, (Harvest House, 1987), 63.

4. MacEachern, 31.

5. MacEachern, 31.

6. MacEachern, 31.

7. Kordan, *No Free Man,* 116.

8. Kordan, *No Free Man,* 116.

3. Off to a Bad Start

1. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 27.

2. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 31.

3. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 35.

4. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 161.

5. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 35.

6. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 29.

4. Building Banff

1. Bohdan S. Kordan, "Enemies of our Country," published in *Military, Civilian, and Political Internments: Examining Great War Internments Together.* (Cornell University Press, 2022), 166.

2. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 153.

5. The Nightmare

1. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 170.

2. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 18.

3. I. Rachamimov & R. Kowner, "Military, Civilian, and Political Internments: Examining Great War Internments Together." From the book *Out of Line, Out of Place.* (Cornell University Press, 2022), 17.

4. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 13.

5. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 171.

6. 5. V.J. Kaye & J.B. Gregorovitch, eds, *Ukrainian Canadians in Canada's Wars: Materials for Ukrainian History,* (Toronto: Ukrainian Canadian Research Foundation, 1983), 81.

7. B. Kordan & P. Melnycky, 50.

8. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 170.

9. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 187.

10. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 171.

11. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 181.

6. Winter

1. Bohdan & Melnycky, 113-115.

2. Kordan, 161.

3. Waiser, 20.

4. Bohdan & Melnycky, 114.

5. Bohdan & Melnycky, 114.

7. The Guards

1. Jared M. Bartels, "The Stanford prison experiment in introductory psychology textbooks: A content analysis," *Journal of Psychology, Learning & Teaching,* (Vol. 14, Issue 1, March 2015, pp. 36-50), 37.

2. Kordan & Melnycky, 55.

3. Kordan & Melnycky, 93.

4. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 167.

5. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 167.

6. Kordan & Melnycky, 81.

7. Kordan & Melnycky, 195.

8. Kordan & Melnycky, 111.

9. Kordan & Melnycky, 54.

10. Kordan & Melnycky, 67.

8. Escape

1. Kordan & Melnycky, 35.

2. Kordan & Melnycky, 73.

3. Kordan & Melnycky, 60.

4. "Escaped Internees Recaptured," *Banff Crag and Canyon*, April 22, 1916, online.

5. "Prisoner Suicides," *Banff Crag and Canyon*, April 22, 1916, online.

9. The Officers

1. Waiser, 16.

2. Waiser, 16.

3. Kordan & Melnycky, 48.

4. "Major Duncan Stuart, officer and lawyer," *Calgary Herald,* June 20, 2014, online.

5. Kordan, *No Free Man,* 166.

6. Kordan & Melnycky, 26.

7. Kordan & Melnycky, 56.

8. Kordan, *No Free Man,* 116.

9. Kordan, *No Free Man,* 171.

10. The Chapter Closes

1. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 131.

2. Waiser, 21.

3. "Bohunk Escapees Recaptured," *Banff Crag and Canyon*, May 6, 1916, online.

4. "Internees Unhappy with Food,"*Banff Crag and Canyon*, April 15, 1916, online.

5. "Compel them to be Decent," *Banff Crag and Canyon*, November 25, 1916, online.

6. "Banff Toboggan Slide," *Banff Crag and Canyon*, January 15, 1916, online.

7. Kordan, *No Free Man*, 178.

Bibliography

Bartels, Jared M. "The Stanford prison experiment in introductory psychology textbooks: A content analysis." *Journal of Psychology, Learning & Teaching.* Vol. 14, Issue 1, March 2015, pp. 36-50.

Basheva, A. & Nikolov, G. *Silence Cries Behind the Barbed Wire: The Internment of Bulgarians in Canada during the Great War (1914-1920).* Winnipeg: Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund, 2020.

Bella, Leslie. *Parks for Profit.* Harvest House, 1987.

Kordan, Bohdan S. *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience.* Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Kordan, B. & Melnycky, P. *In the Shadow of the Rockies: Diary of the Castle Mountain Internment Camp 1915-1917.* Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1991.

MacEachern, Alan. *Natural Selections: National Parks in Atlantic Canada, 1935-1970.* Kingston & Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001.

Luciuk, Lubomyr. *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920.* Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001.

Morton, Desmond. "Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada during the First World War." *Canadian Historical Review.* Vol. 55 Issue 1, March 1973 pp.32-58.

Rachamimov, I. & Kowner, R. "Military, Civilian, and Political Internments: Examining Great War Internments Together." From the book *Out of Line, Out of Place.* Cornell University Press, 2022.

Waiser, Bill. *Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada's National Parks.* Toronto: Fifth House Publishing, 1995.

**Newspaper Articles**

"Banff Toboggan Slide." *Banff Crag and Canyon*. January 15, 1916.

"Bohunk Escapees Recaptured." *Banff Crag and Canyon*.May 6, 1916.

"Compel them to be Decent." *Banff Crag and Canyon*. November 25, 1916.

"Escaped Internees Recaptured." *Banff Crag and Canyon.* April 22, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/7/1916-04-22-BCC-Escaped-Internees-Recaptured.pdf

"Internees Unhappy with Food." *Banff Crag and Canyon*. April 15, 1916.

"Major Duncan Stuart, officer and lawyer." *Calgary Herald.* June 20, 2014. https://www.pressreader.com/canada/calgary-herald/20140620/281835756779683

"Our Interned Aliens." *Red Deer News*. June 12, 1918. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/31/1918-06-12-RDN-Our-Interned-Aliens.pdf

"Prisoner Suicides." *Banff Crag and Canyon*. April 22, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/7/1916-12-30-BCC-Prisoner-Suicides.pdf