Walking Tour

The Heart of New France

Quebec City in the French Era

Andrew Farris

The story of Old Quebec is fundamental to the history of Canada. It began as a French colony in 1608 that controlled access to the Saint Lawrence River, and the Great Lakes beyond. Over time it was heavily fortified to defend against France's imperial rivals, and was made the seat of colonial government for all France's possessions in Canada, which were known as New France. In 1759, the city finally fell to the British, a pivotal event that would shape all Canada's future history.

On this tour we will start in the Lower Town where Samuel de Champlain first built l'Habitation, the first permanent European settlement in Canada. Afterwards we will climb the Breakneck Steps and take a tour of the Upper Town, and learn about life in New France in the 17th and 18th Centuries. Finally we'll walk along the Dufferin Terrace and climb the promontory up to the fort for a fantastic view of the city.

The tour route requires walking up two sets of stairs.

1. The Promontory

1890

Here in the shadow of the Quebec promontory, we're standing near the site of the first permanent European settlement in Canada. It's no surprise that this was the site chosen by French explorers for a settlement: The towering bluffs dominate the Saint Lawrence River, the highway to the Great Lakes and beyond. The Algonquin word "Kebec", means "where the river narrows." It's where Quebec gets its name.

The first recorded arrival by Europeans on this spot was in 1535, when a French expedition led by Jacques Cartier made landfall and was led to the Iroquois village of Stadacona, just a short distance from here. Harsh winters and war with the Stadaconiens ultimately meant Cartier's expeditions failed to establish a permanent colony, but they brought Canada, as the Stadaconiens called their village, into the European imagination.

* * *

This was a fateful winter for Canada's Indigenous peoples as well: European-introduced diseases are thought to have killed perhaps 50 of Stadacona's 500 inhabitants.1 It was an ominous sign of what was to come.

Cartier returned to France in the spring, and came back with a larger expedition in 1541, intending to establish a permanent colony. However, relations with the Stadaconiens broke down and the expedition found themselves virtually besieged in their little fort. After another brutal winter, Cartier abandoned the colony and returned to France.

He brought with him barrels of diamonds plucked from the bluffs of Cap Diamant above you now. He hoped to use them to stoke interest in future expeditions. He was shocked and disappointed when French experts decided these "diamonds" were actually just quartz.

Cartier's failure meant no new expeditions up the Saint Lawrence River would be launched for 60 years.

2. The Father of New France

1898

Just ahead of you and to the right is the Place Royale, the exact spot of l'Habitation, the first permanent European settlement in Canada. The buildings no longer survive, but you can see plaques marking out the original area.

The settlement was established by the legendary French soldier, cartographer, and explorer, Samuel de Champlain. On July 3, 1608, he landed on this spot and quickly built a post where the French could trade furs with the Montagnais Indigenous, who controlled this region at that time.

There was no sign of the Stadaconiens that Cartier encountered. At some point since his departure 65 years before, their village had been abandoned--perhaps because of disease or wars with neighbouring Indigenous peoples. By the 1620s Champlain's tireless efforts had put the settlement on a firm footing, and it became known as New France.

* * *

Champlain was "a consummate diplomat", and knew if he was to get the help he needed, he needed to make military alliances with the Indigenous, and aid them in war.2 In the summer of 1609 he forged an alliance with the Algonquins and Hurons against the Iroquois, beginning a long and complicated chapter of Canadian history where shifting alliances of European and Indigenous peoples waged frequent wars.

Champlain's settlement was centered on a remarkable three-storey wooden structure, built somewhat in the fashion of a French aristocrat's manor. It was part castle--including a palisade, watchtower, cannons, and even a moat--and part luxury estate, with fine imported glazed windows and tapestries. Even though it was located at the foot of the promontory, it could still control access to all ships navigating the Saint Lawrence.

Back in France, Cardinal Richelieu was so impressed with the profits from the Canadian fur trade that in 1627 he oversaw the founding of the Compagnie des Cent-Associes, which was to control all trade in New France and manage the colony's development. Champlain was to be the governor.

Unfortunately, at that time France and England were at war, and the British privateer Sir David Kirke was determined to conquer Quebec. In 1629 Kirke succeeded in seizing French food shipments to the colony, and forced Champlain and the 100 starving colonists to surrender. England took control of the colony.

After treaty negotiations, Quebec City was returned to France in 1632, but not after Kirke and his men had burned most of it down. Champlain, undeterred, resumed his post as governor and set about rebuilding Quebec City. His boundless energy and expansive vision for New France in those years set Quebec on a path towards a bright future, though Champlain wouldn't be around to see the fruits of his labours: he died on Christmas Day, 1635.

As you walk past the Place Royale ahead, read some of the plaques and think about how much Quebec has changed in the 400 years since Champlain's l'Habitation stood on this spot.

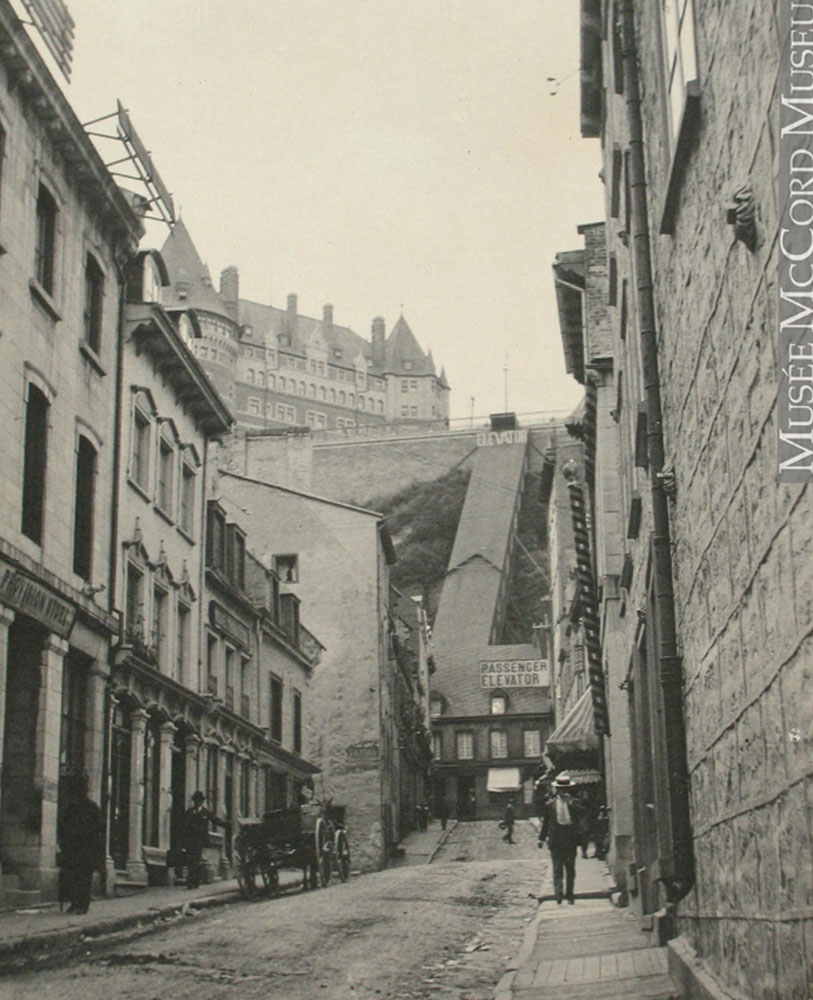

3. The Lower Town

1870

These are the famous Breakneck Steps (though, fortunately there is no record of anyone ever breaking their neck on them).1 The stairs were first built all the way back in 1635, the year of Champlain's death. The stairs connected the two distinct areas of Quebec City that took shape around this time: the Upper Town and the Lower Town.

* * *

If you look around the streets of the Lower Town today, you can see the unmistakable stamp of the Ancien Regime urban design the colonists brought with them. As the historian Remi Chenier observed, Quebec City "was a reflection" of 17th Century French society.3

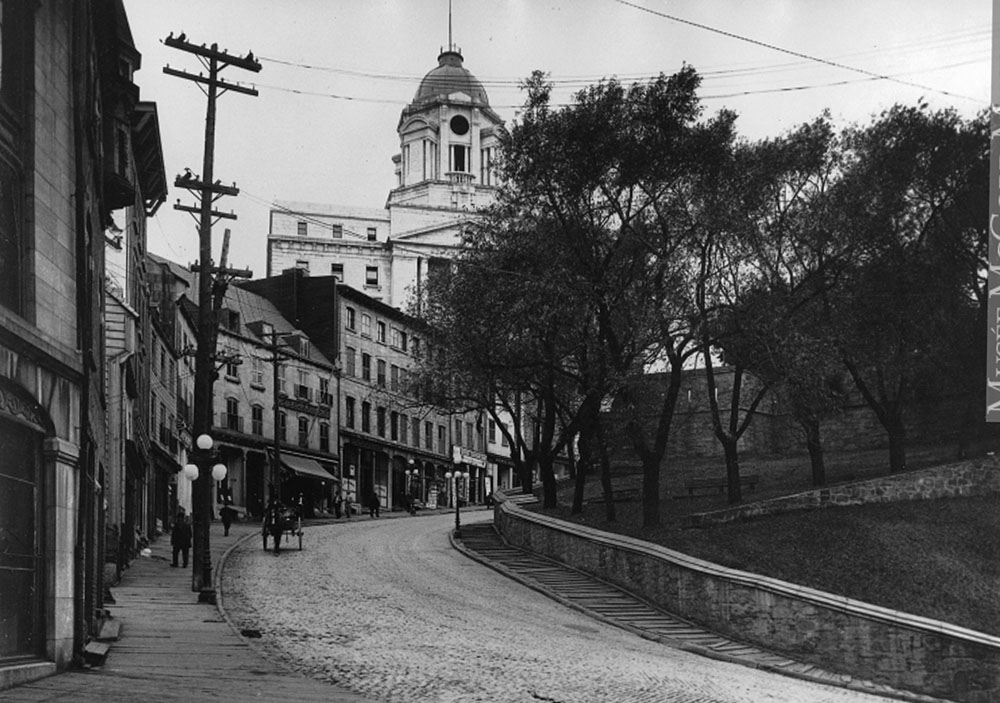

4. Canada's First Immigrants

1916

After ascending the stairs, we have a view up the Côte de la Montagne towards the Upper Town. The cupola of the old post office dominates the view. The post office was built in the late 1800s in the Second Empire Style, but it is a reminder of the importance of the postal service from the colony's earliest days to maintain close bonds with France.

Ships from France and French colonies in the Caribbean frequently called at Quebec City, an average of 40 a year by the 1720s.1 They brought trade goods, colonists, and a surprisingly large number of temporary workers.

* * *

We're proud to note that one of the earliest to arrive in 1634, Zacharie Cloutier, is the direct ancestor of On This Spot's Chief Operating Officer, Sean Edmunds.

The voyage from France to Quebec was long and dangerous: it's thought 5% of those making the crossing died en route. For many, the risk was worth the shot at a fresh start in life. Most were young men, and two thirds were between the ages of 16 and 30. They predominantly came from the overcrowded French cities, and were mostly artisans or craftsmen instead of rural peasants. At the time 80% of French people were rural peasants, but only 27% of the arrivals in New France were.3

As the historian Leslie Choquette writes, "immigrants to New France did not form a representative cross-section of the French population. As single, young adults from dynamic urban areas, they must have been part of an unusually adventurous, enterprising group in contrast to the stereotype of the ignorant, conservative peasant."4

5. Building a Fortress

McCord Museum N-0000.193.188.2

1859

This is the Grand Battery in Montmorency Park. The cannons in front of you are one of the many obvious reminders of Quebec City's turbulent history that can be found throughout the Old Quebec. With batteries like this one, the French could dominate the Saint Lawrence River, and with it access to the continental hinterland. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, when European powers and their Indigenous allies fought savagely for control of the Americas, and a strategic prize like Quebec City needed all the defenses it could get.

* * *

From 1642 to 1698, the French continued Champlain's alliance with the Algonquins and Huron, and fought sporadic wars against the British and Dutch and their powerful ally, the Iroquois Confederacy. This series of wars was fought mostly for control of the lucrative fur trade, so they are called the Beaver Wars.

The British and their American colonists sent a fleet to conquer Quebec City in 1690, but were beaten back by the punishing bombardment from guns like the ones you see here. Another attempted invasion in 1711 failed when the British fleet foundered on the shoals.

Seizing Quebec City would be no easy task.

6. Church and State

1908

This is the Seminaire de Quebec, a school for Jesuit priests founded by New France's first bishop, Francois de Laval in 1663. The school trained parish priests to be dispatched as far away as Louisiana, while missionaries were trained to fan out amongst the Indigenous peoples and work to convert them to Roman Catholicism, though these efforts met with only limited success. Sprawling compounds of the various Catholic religious orders occupied much of Quebec City's Upper Town, a dramatic illustration of the church's proximity to state power.

* * *

Catholicism was not, however, a monolith. Instead it contained a whole spectrum of religious orders. Among those orders that maintained a presence in the Upper Town were the Recollets, Jesuits, Augustinians, Ursulines, Sulpicians, Soeurs Grises, and Capuchins.

After the British conquest the Seminaire became a teaching college, and later formed the nucleus of Universite Laval, which was officially established in 1852, making it the oldest university in Canada.

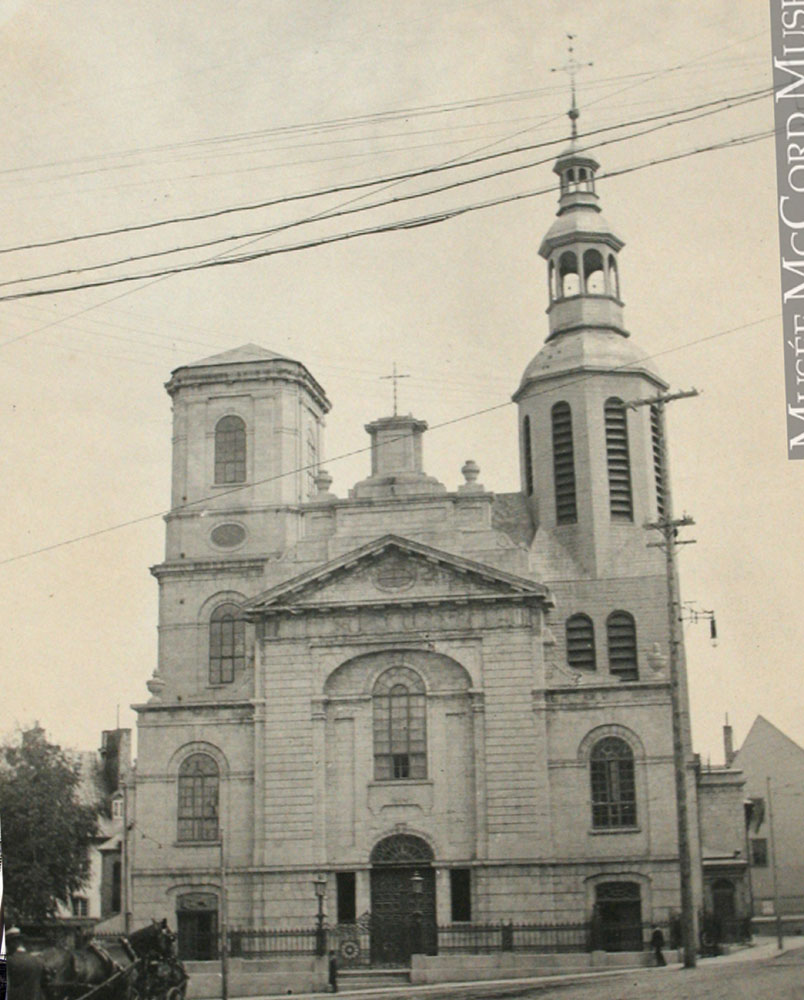

7. The Catholic Way of Life

1898

You're standing now in front of the Notre-Dame de Quebec Basilica, "probably the most extensively expanded and transformed structure in Canada's history still dedicated to its original purpose."1

Built in 1647 as the first stone church in the city, it was the seat of the Quebec City Diocese and the Bishop of New France. This makes it the "ancestor of all the Catholic parishes that have spread across Canada and the United States."2

* * *

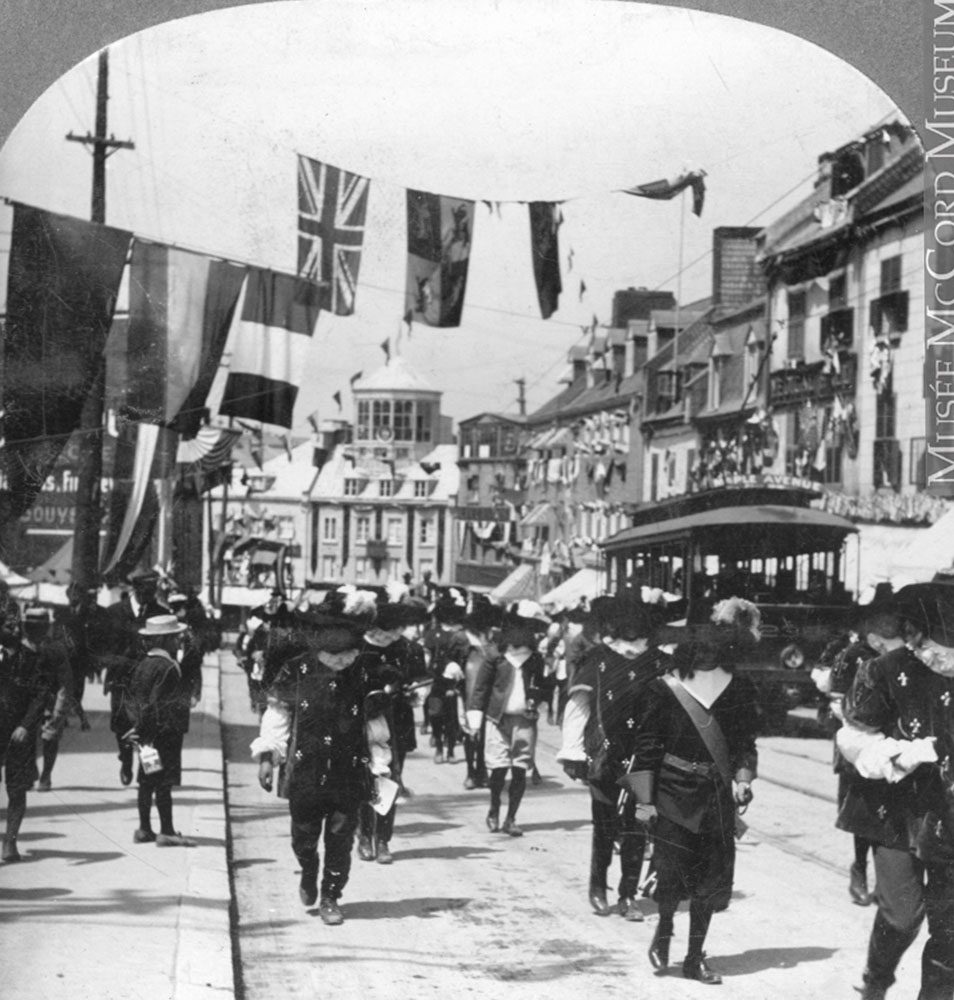

8. Culture of New France

1908

A parade marking the 300th anniversary of the founding of Quebec. The occasion was the largest celebration the city had ever seen, including weeks of parades, festivals, and reenactments, and were attended by the soon-to-be-crowned British monarch George V. As we can see, the participants are wearing 17th Century period costume, the kind worn by the early colonists of New France.

* * *

It's no surprise then that the colonists of New France were extremely proud of the culture they brought to North America. They designed Quebec to look like a French ville, kept up with the latest fashions popular at the court of Versailles, ate French cuisine, read French writers and philosophers, and imported French art. After the British conquest of Quebec in 1759, the original colonists were forced to fight to maintain these traditions in the face of a new Anglo cultural hegemony.

That struggle continues to this day, and it's been a remarkably successful one. For over 250 years the Quebecois have safeguarded their unique cultural patrimony in the face of a relentless drive to assimilate. It's impossible to overstate the cultural legacy left on that nation of Quebec, and Canada as a whole, by the 150 years of French rule.

9. Centralizing Tendencies

1915

The building on the left is the City Hall of Quebec City, completed in 1896. The city hall is the seat of the municipal government, which was only actually founded in 1796, after the French era. The curious fact that Quebec City did not have a municipal government when it was a French colony was a deliberate decision by Louis XIV, and sheds some light on the highly centralized government he established in the Royal Colony in 1663.

* * *

The royal takeover established Quebec City as the capital of New France. Two royal appointees would carry out the king's will in New France: a Governor General who commanded the military, and an Intendant with a vast portfolio for domestic administration. They answered to the king's dynamic Minister of Marine Jean-Baptiste Colbert at Versailles. These two officials, housed in the opulent Chateau Saint-Louis and Intendant's Palace respectively, exercised direct control over all the French settlements in Canada. A Sovereign Council of local elites acted as a final court of appeal, but true power lay with the Governor General and Intendant, "which inspired historians to speak of a two-headed government."1

As part of Louis's drive to centralize the government under his control, no municipal government was ever founded to prevent any potential for deviation from the royal will.

This structure of government proved very successful in overseeing dramatic growth of the colony from 1663, right up to the twilight of New France in 1759.

10. Women in New France

1865

This complex of buildings holds a special place in history: This is the Ursuline Convent, the oldest institution of women's education in North America. The Ursuline Sisters first arrived in 1639, and moved into a monastery built on this spot soon after. Some buildings in the complex date to the 1680s, making them the largest surviving 17th century buildings in Canada. In the early years the nuns educated Indigenous girls, and soon after began educating the young Canadien girls born in the colony. They have continued to do so ever since.

* * *

Nevertheless the preponderance of men became a major issue, and when Louis XIV took control of the colony in 1663 he began sponsoring women of a marriageable age who wanted to travel to Quebec--the famous Filles de Roi, or King's Daughters. In all some 850 young women took the king up on his offer.

The gender imbalance remained an issue throughout the French era, and by one estimate male immigrants outnumbered their female counterparts 4 to 1.1

For those women who made a home in Canada, life was often one of unremitting toil. Women were expected to cook, maintain the house, sew, and, of course, bear children. Many women had ten or more children.2 Yet there were opportunities open to them, and it was relatively common for women to own property, manage businesses, and work as teachers and nurse

11. The Seven Years War

1930

This is the house that the mortally wounded Lieutenant General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm was carried to after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. By the next morning he was dead, and with him the dream of France's North American empire.The battle was the culmination of years of fierce campaigning in the North American theatre of the Seven Years War.

* * *

Though Samuel de Champlain founded Quebec 12 years before the Pilgrims ever landed at Plymouth Rock, the French government's belated and intermittent efforts to settle Quebec were entirely outmatched by the explosive growth of Britain's American empire: When the war started in 1756, New France had a population of 60,000, but over two million British settlers lived in the Thirteen Colonies.1

The French relied heavily on their Indigenous allies to even the score, the Wabenaki Confederation, Algonquin, Ottawa, and many others. Montcalm himself was able to win a number of tactically brilliant victories against the British and their American colonists around the Great Lakes. But outnumbered and deprived of French aid by a British naval blockade, the French and their Indigenous allies were driven back. By 1759 they had retreated to their final redoubt: Quebec City. It was here they made their final stand.

12. The Fall of Quebec

1761

This painting was created two years after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Conquest of Quebec. We're looking across the Place d"Armes towards the Recollect Friars Church on the left. Look closely and you can see the walls of the buildings are perforated by cannonfire, and their interiors gutted by fire. This was the work of General Wolfe's artillery in the three month siege leading up to the battle. The troops drilling in the square are British regulars.

* * *

By mid-September, with winter closing in, Wolfe was nearly ready to raise the siege and move to winter quarters. In a final gamble, he decided to sneak his ships under the guns of the fortress, navigate the treacherous currents of the Saint Lawrence, and land his entire army at L'Anse-au-Foulon, a couple kilometres upriver from Quebec--all at night. Once ashore he and his men would scale a 50 metre cliff and then deploy on the fields behind the fortress before the French could counterattack. This was an almost unbelievably risky amphibious operation, which could have just as easily ended in total disaster for the British.

On September 13, 1759, Wolfe's men pulled it off. The British achieved complete surprise. When the sun rose that morning 4,500 British regulars were arrayed in battle order on the fields opposite the fortress.

Up to this point Montcalm had wisely declined to offer battle despite Wolfe's best efforts. Many military historians argue he could have easily done the same that morning too, and waited out the British again from inside the walls of Quebec City. For whatever reason, history doesn't record what happened in those crucial moments, he decided to march his army out onto the plain. Some decisions in history ripple down through the centuries.

While the forces were evenly matched in numbers, many of Montcalm's troops were poorly trained militiamen, while the entire British force consisted of battle-hardened regulars. The two armies met and exchanged volleys of musket fire. 15 minutes later the French were routing, and both commanders lay dying--one of the only battles in recorded history with this distinction.

Most of the French army escaped, but moved west towards Montreal, leaving Quebec poorly defended. The British renewed the siege, and five days later the new French commander signed the Articles of Capitulation, turning the city over to the British.

Endnotes

1. The Promontory

1. Bernard Allaire, "Jacques Cartier," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Aug. 29, 2013, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

2. The Father of New France

1. M. Trudel, M. d'Avignon, J. Marsh, "Samuel de Champlain," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Aug. 29, 2013, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

3. The Lower Town

1. "Breakneck Stairs and Mountain Hill," Ville de Quebec, accessed Feb. 21, 2021, online.

2. Leslie Choquette, "Population: Immigration," Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

4. Canada's First Immigrants

1. Timothy Foran, "Economic Activites: Fur Trade." Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

2. Leslie Choquette, "Population: Immigration," Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

3. Choquette, online.

4. Choquette, online.

7. The Catholic Way of Life

1. "Notre-Dame de Quebec: Basilica-Cathedral," Quebec City Holy Door, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

2. Claire Gourdeau, "Population: Religious Congregations," Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

9. Centralizing Tendencies

1. Marie-Eve Ouellet, "Colonies and Empires: Governance and Sites of Power," Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

10. Women in New France

1. Leslie Choquette, "Population: Immigration," Virtual Museum of New France, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

2. Choquette, online.

11. The Seven Years War

1. National Battlefields Commission, "1759: From the Warpath to the Plains of Abraham," Virtual Museum of Canada, 2005, accessed Feb. 25, 2021, online.

Bibliography

Allaire, Bernard. "Jacques Cartier," The Canadian Encyclopedia. Aug. 29, 2013. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jacques-cartier

Choquette, Leslie. "Population: Immigration." Virtual Museum of New France. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/immigration/

Foran, Timothy. "Economic Activities: Fur Trade." Virtual Museum of New France. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/economic-activities/fur-trade/

Gourdeau, Claire. "Population: Religious Congregations," Virtual Museum of New France. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/population/religious-congregations/

National Battlefields Commission. "1759: From the Warpath to the Plains of Abraham," Virtual Museum of Canada. 2005. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/edu/ViewLoitLo.do%3Bjsessionid=CB75229632D22337FFE2300D27C81FD8?method=preview&lang=EN&id=23881

Ouellet, Marie-Eve. "Colonies and Empires: Governance and Sites of Power." Virtual Museum of New France. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtual-museum-of-new-france/colonies-and-empires/governance-and-sites-of-power/

Quebec City Holy Door. "Notre-Dame de Quebec: Basilica-Cathedral." Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. http://holydoorquebec.ca/en/cathedral

Trudel, M., d'Avignon, M., Marsh, J. "Samuel de Champlain," The Canadian Encyclopedia. Aug. 29, 2013. Accessed Feb. 25, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/samuel-de-champlain

Ville de Quebec. "Breakneck Stairs and Mountain Hill." Accessed Feb. 21, 2021. https://www.ville.quebec.qc.ca/en/citoyens/patrimoine/quartiers/vieux_quebec/interet/escalier_casse_cou_cote_de_la_montage.asp