Walking Tour

Life in Early Parry Sound

The Town's Story

Joshua Edmunds

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1335

In this tour we will take a step back in time and look at Parry Sound through the eyes of those who lived here in the town's early days. The significant resource potential of the region, and Parry Sound's strategic location on Georgian Bay, helped it develop from a frontier post into an industrial hub in a few short decades.

As the lumbermen felled the dense forests of white pine, new possibilities came into view. Great companies emerged, themselves headed by dynamic pioneers, such as William Beatty Jr., Patrick McCurry, and J.C. Miller.

Yet a town's destiny is not defined simply by its most prominent citizens. Advances in technology and economic development spurred population growth and led to the building of mills and waterworks, dockyards and fire halls. The quickening pace of change made Parry Sound's citizens forward-looking, and they eagerly wondered what the future held in store. What ensued was a redefining of the old civic traditions, changes that have woven a rich tapestry of history which we may now explore.

This tour will begin at the docks, which were Parry Sound's connection to the outside world. It will then continue into the downtown core, where the shops, schools, and churches that were built gave Parry Sound its unique character.

This project is a partnership with the Parry Sound Business Association and the West Parry Sound District Museum.

1. Arriving in Parry Sound

This is a picturesque view of steamers coming into port at Parry Sound. These vessels carried goods for trade, supplies, and passengers, and were the economic life force of the Great Lakes region in the 19th and early 20th century.

* * *

Until the building of roads and railroads, in the 1860s and 1890s respectively, the dock was the only point of contact with the outside world. During the winter months, when the bay would freeze, the entire community would plunge into isolation from the outside world, unlikely to receive new visitors until the spring thaw.

2. Building the Railway

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1347

1907

To any 19th century viewer, the train was the symbol of modernity. Steam engines were the cutting-edge of technology, and could reduce an overland journey of months to days. Parry Sound's citizens recognized the incredible value of these ships and from the 1880s, adamantly petitioned the Canadian government to subsidize construction of a railway connection. They sought to have a spur line built, linking Parry Sound to the Northern and Pacific Junction railway, which was then in construction to the north. The CPR Trestle bridge pictured here embodies the final pages in the long tale of Parry Sound's struggle for a railroad.

* * *

Building a railway was no simple task: vast amounts of iron would have to be purchased, processed, and fashioned into track; forests would have to be cleared, mountains exploded, and roadways built, all under the watchful eye of hired experts. To raise the necessary money, McCurry lobbied relentlessly for construction subsidies from both the provincial and federal governments. Through incessant petitioning, McCurry convinced local politicians to put forth a request for federal financing for the Colonization Railway. Despite McCurry's efforts, the lobbying in Toronto did not have much effect. In Ottawa he was more successful, obtaining a federal subsidy of $3,200 per mile of track between Parry Sound and the village of Sundridge. But there were conditions to this agreement: the cost of the railway was not to exceed $128,000, and construction was to commence in two years, and be completed within four.

Despite this victory, the PSCR would continue to languish as little more than a dream for four more years. It was clear that more money was needed more funding. What the directors of the railway needed was provincial support. They returned to Toronto in March of 1889, and descended upon the provincial legislature. There, MPP Samuel Armstrong Jr., through a combination of fiery rhetoric and clever statesmanship, attained a provincial subsidy of per $3,000 mile of track. Armed with this renewed support from Ottawa and Toronto, the directors of the railway contracted with William G. Reid of Montreal to complete their project.

The project faced daunting challenges. Chief Engineer S.R. Poulin wrote of the roughness of the terrain, which imposed deviations in the line and dramatically increased its length and raise the costs by 15%. To offset these costs, Poulin proposed the construction of a series of trestle structures over the valleys.1

The trestle bridge you see here is an example of the type Poulin proposed, though it would not be built for another 20 years.

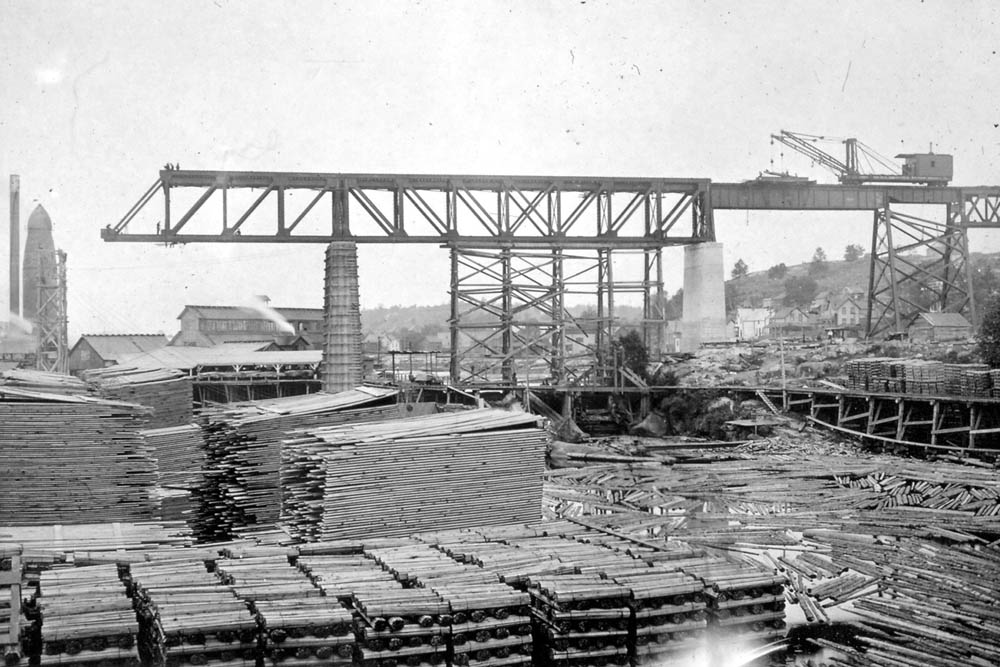

3. Booth's Betrayal

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1350

1907

Construction of the CPR railway trestle, which followed the PSCR in the early 1900s. The difficult terrain was an ongoing problem for the PSCR. The railway corporation struggled to remain solvent, and it seemed every week new obstacles were thrown in their path. In May 1891 the corporation began exploring options of amalgamating with one of the other railways running through Ontario, which If amalgamated, the debts, duties and obligations created under the Colonization Railway would be subsumed by the parent company.

* * *

The inspection did not go well. Although the tracks and roadbeds were constructed in accordance with the contract, the necessary water tank, engine house, turntable and station in the first section had yet to be built. This reduced the payout on the subsidy by $3,990 -- leaving the company with $59,220. Nevertheless, the gambit paid off: Ridout's report was enough to secure a federal approval for the next batch of subsidies to help them complete the line

In the spring of 1893, the PSCR was sold to J.R. Booth, who infamously rerouted it through Parry Island, where he created the port of Depot Harbour. Four years later the line was complete, and a year after that, all the necessary facilities including a massive one-million-bushel grain elevator, over 2000 feet of dock space, and extensive freight sheds.

The inhabitants of Parry Sound, who had invested so heavily in the railway, were livid. Depot Harbour was an existential threat to the town: all the region's people and commerce would be sucked away to Depot Harbour, and Parry Sound would wither away.

What ensued was a storm of lobbying by the businessmen of Parry Sound. They succeeded in having the James Bay Railway agree to connect Parry Sound to their Ottawa and Arnprior line in return for a grant of $20,000. The line was completed in 1902 and offered service to Parry Sound at one coach per day. Parry Sound finally got its railway. This was not the railway you see here however.

In 1904, representatives of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) met in Parry Sound with the Board of Trade to discuss the construction of a railway between Toronto and Sudbury. The CPR made it clear they wanted Parry Sound on their line: the waterfront provided sufficient frontage for docks and elevators.

The James Bay Railway was determined to maintain their monopoly of rail access to the town and sought to bar the CPR's proposal. What ensued was a fierce round of legal actions before the Supreme Court of Canada, who finally declared in 1905 that the CPR did in fact have jurisdiction to build a railway into the town.

The CPR wasted no time following this decision: they awarded hundreds of contracts for clearing land, grading, constructing bridges, and laying down track. 5,000 working men surged into the town to begin construction.1

The first CPR train crossed the trestle bridge viaduct on June 14th, 1908. It had been a journey thirteen years in the making. It had strained the finances of the community, and wrought deep-seated animosity towards businessmen like Booth, who might renege on their promises.2

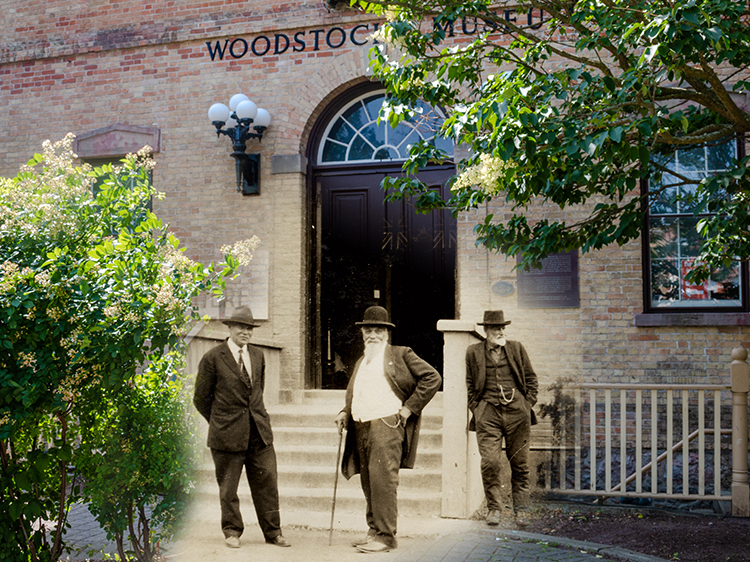

4. The Oddfellows Hall

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1140

1897

This building belongs to the Independent Order of Oddfellows. It has retained a prominent position on James Street since its construction in 1897. Designed by the Toronto firm, Simpson and Ellis, the IOOF temple was on the third floor, while the lower levels housed offices and stores. Steeped parapets, three arched windows, and detailed brickwork were integral to the composition of the Italianate facade, a style popular at the time.

* * *

Without any savings or family to rely on, young breadwinners in England joined "friendly societies"--or fraternal organizations--that filled the gap left by medieval guilds. These societies provided vital disability insurance in addition to countless other benefits. By joining organizations such as these, a young man would be able to establish important business connections, make lifelong friends, and find some degree of protection from the vicissitudes of life.

The I.O.O.F. had over two million members in the United States and Canada, making it one of the largest providers of sickness or disability benefits prior to the existence of any modern insurance corporations. Enamoured with exotic rituals and bizarre clothing, fraternal societies might now be considered as somewhat bizarre, but in the 19th century, organizations like the IOOF played an important community role. Fraternal insurers provided an efficient delivery of working-class sickness insurance that commercial insurers simply could not match.

As interest in the IOOF declined in the 20th Century, the insurance services were retired. This was because they were chiefly for the young men, being a young man's benefit. Without any infusions of new blood into these societies, such services were deemed to be no longer necessary. Instead, the fraternal society turned to social activities and ritual as its main lure for new recruits.1

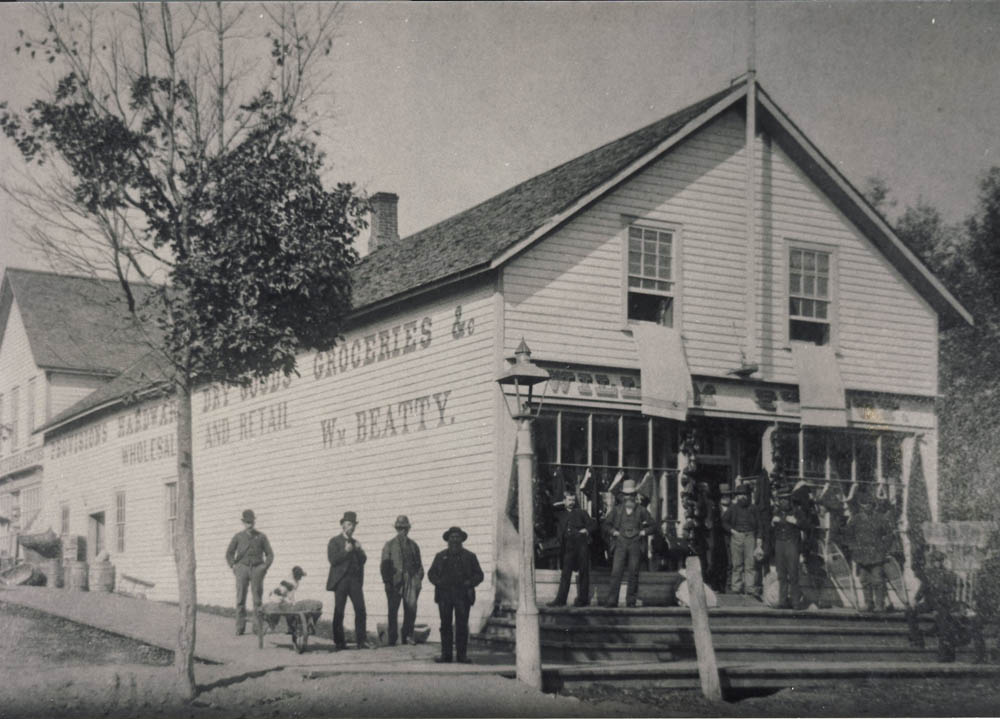

5. Founding Parry Sound

West Parry Sound District Museum 1998.135.001

Pictured here is the Beatty Grocery Store, owned by William Beatty Jr., the most prominent figure in Parry Sound's early history. The store, which survives with some heavy alterations today, was the centre of activity around which the community of Parry Sound grew.

* * *

The Beatty's were impressed by the natural resources on the land around what would become Parry Sound, and quickly obtained timber rights to 234 square miles of land around the area. The mill took off and was producing 3.2 million board feet of lumber by 1871, employing more than eighty men. One of three owners, Beatty Jr. demonstrated the most interest in the investment and began funding infrastructure development of the area. He increased accessibility to the sound by overseeing the construction the Parry Sound Road in 1867, which connected to the Muskoka Road. It was Parry Sound's first real land link to the outside world, though a crude one at that.

In May 1867, J.W. Beatty & Company purchased 2,198 acres at the mouth of the Seguin River, marking out a townsite called Parry Sound. Beatty Jr. worked hard to attract settlers to his burgeoning community. Within two years Parry Sound had a doctor, a schoolteacher, a newspaper, a stagecoach service, and a grist mill. For his leadership, Beatty was awarded the name "Governor." Modern Parry Sound had been born. 1

6. Trekking to the Store

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1293

1905

Here's a picture of the City Meatmarket, a local butcher that operated in Parry Sound in 1904. Within the rural Canadian consciousness, stores held a firm role within the community, and were centres of public life.

* * *

John Macfie describes his own childhood, where he spent many a night migrating from store to store:

"During winter, no small measure of that warmth radiated from a roaring box stove. Around its perimeter, men [and women] gathered after completing their purchases, and foot travellers soaked up a reserve of heat before heading home in the cold darkness…

"Temperatures could plummet, or flurries swell to blizzards between seven and ten p.m. If a gang started together, horseplay kept us warm the next mile. Then the crowd thinned as lanes and sideroads were passed, and blankets of silence descended, especially in the brooding groves of spruces in whose branches wildcats were said to lurk. The handle of the coal oil jug passed steadily from cold hand to cold hand until the welcome farm gate was attained."1

For kids, the store was the place to be: boys from outlying farms would regularly hike into town on those store nights. To them, visiting the store meant being somewhere that was illuminated and had a crowd. For Macfie, that might involve a seven-mile round trip trek. Many a Toronto Maple Leafs fan came into existence within the walls of the village store, when youngsters, sequestered away in some corner, might congregate and listen, wide-eyed, to every Maple Leafs game broadcasted over CBC Radio. Few rural homes had radio back then, so the store was the known nexus where one could catch up on the latest hockey news.

7. The Cars Arrive

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1970

1920s

Here we see James Street, well in the midst of the travel revolution brought on by the personal automobile. The popularization of the automobile brought Parry Sound into a new age. Vehicles and newly improved road access brought a new source of tourists to town. Suddenly the steamships, which had been the main way for visitors to visit, began to fall into decline.

* * *

The first wagon roads into Parry Sound, now known as Provincial Highway 124, go as far back as 1867, when William Beatty took the first contract to build the first few miles of the Great Northern Colonization road. Early on, the traffic on the road was largely limited to vehicles pulled by oxen or horses. It was not until the First World War that self-propelled vehicles with internal combustion engines saw regular use. Their increasing popularity meant a reimagining of the roadways, and the way they were managed. Potholes and poorly draining surfaces were unacceptable, and infrastructure was reworked to be resilient to the ravages of time and weather.

The new visitors brought money with them, which benefited the whole community. Local businesses sought to reorient themselves to cater to this new demographic. Muskoka blossomed, and the tourism industry entered into golden age of the weekend cottage retreat.

8. Kids' Life

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1477

A group of teenage boys on James Street. You can see the fire hall in the background at centre left. To the right is an old blacksmith shop which does not survive. At left is the old Brunswick Hotel before it burned down. In an age before computers, TV, or even radio, one could reliably expect hordes of kids to be wandering the streets until their curfews. The rationale for hanging around was simple: get out of the house, and meet up with some other kids. The natural point to gravitate towards was the store or the schoolyard, where kids could meet, play, share gossip and hockey scores.

* * *

9. The Baptist Church

West Parry Sound District Museum 1998.003.019

The First Baptist Church has sat quietly on the corner of McMurray and James since its construction in 1888. Notable design features include its shingle style, with patterned shingles, rubble coursed stone foundation, and multi-paned windows.

* * *

The Church brought many devout worshipper together. During this time of celebration, many more members demonstrated their love for God and the church, by supporting deacons, clerks, treasurers, committees of property, music, Christian education, and the Women's Association. Some members even moved to support the Temperance Laws (a personal stand), and a War Services Committee who saw the church "take special care of its own 'boys and girls' who had enlisted."1

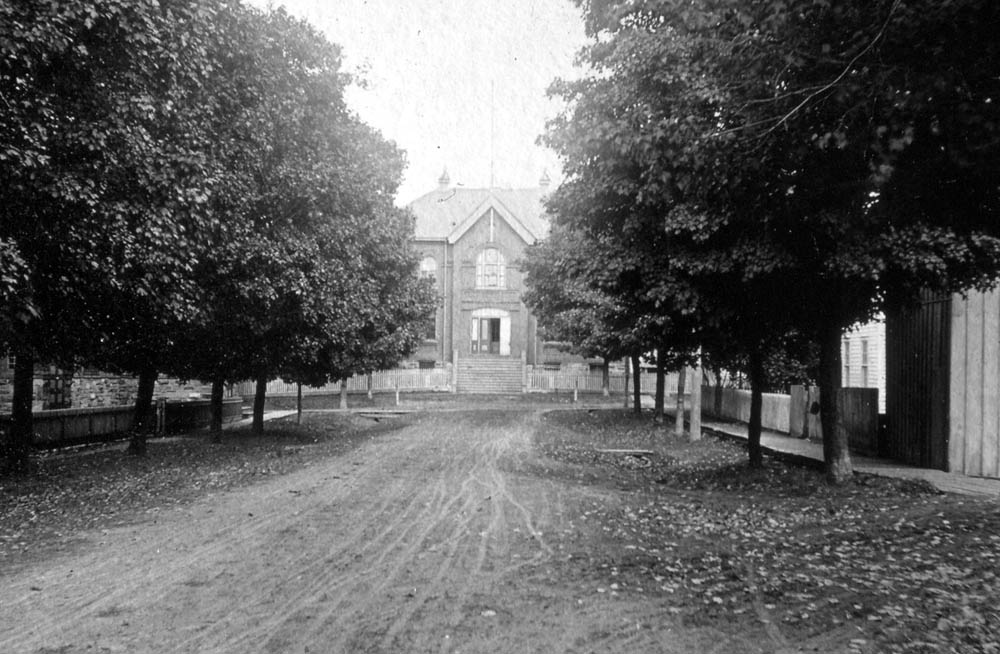

10. Crime and Punishment

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.973

Pictured here is the Parry Sound Court House, the first courthouse built in Northern Ontario. Designed in 1871 by Kivas Tully, the architect of Victoria Hall in Cobourg, the Courthouse began its life as court of law, jail, and registry office. Its iconic features are the central pavilion with wings, its arched windows, and low relief brick detailing, indicative of the extremely British style of Georgian architecture popular in Ontario at the time.

* * *

It was the savage murder of seventy-year-old Michael James Davis in his hotel room 1910 that horrified the little community. The accused, Louis Young, was a young man from Philadelphia, who had been travelling throughout Ontario, eking out a meagre existence as a transient labourer.

In those days, transients often travelled by foot, and hitchhiking, or hopping on passing freight trains. Young already had a criminal record in the United States for petty crimes when he arrived in Parry Sound in 1910. He lived in the East Ward, then a magnet for transients. Such rogues sometimes targeted naïve, and all-too trusting people.

Davis had made the trip to Parry Sound with the intent of negotiating a loan of $300 from the Bank of Ottawa. A considerable fortune at the time, Davis' loan made him a prime target for someone with cruel purposes. Davis' friendly nature didn't help.

The old farmer met Young on the streets outside of the hotel, where Young described his own story of hardship and deprivation. Moved by his words, Davis invited the young man inside the hotel, offering to buy him a meal. It was then that Davis disclosed his reason for being in Parry Sound, telling him of the considerable loan which he was about to receive. No doubt this information sunk into Young's mind. Having been fed, Young parted company with Davis, and no more was noted of either until later that evening.

At around 11 pm, the night manager, Chris Dixon, noted another transient, by the name of James Donaldson, had entered and inquired about Louis Young. Donaldson was a friend of Young's.

Dixon had had no recollection of meeting Young, who was not staying at the hotel. Upon further nudging, Donaldson insinuated that Young could be found in Davis' room. On Donaldson's urging, Dixon climbed the hotel steps towards Davis' room, and tried the door--which was locked. Past the door there was an absolute silence. Not wanting to wake his guest, Dixon returned to the lobby and informed Donaldson that he must have been mistaken: Young was not in the room. To make doubly sure, Dixon rifled quickly through the register, upon which all guests and visitors were documented.

It was then that Young appeared and descended the stairs; moving in the direction of the washroom and clearly trying to look inconspicuous. Donaldson noticed him and cried with alarm: there was blood on the young man's shirt.

Young broke into a sprint clearing the lobby and the hotel doors, running out onto Parry Sound Road. In hot pursuit was the hotel manager, Joseph Rawson. Young was caught by Rawson less than two hundred yards from the hotel, where he offered very little resistance. Upon being bound and secured, he was marched back to the scene of the crime.

It was a grim scene that awaited them: the body of Michael Davis was found lying atop his hotel bed, fully clothed and facedown. His head and face bore severe blunt force trauma and lacerations, a terrible end for a kind and gentle pillar of the community. His pockets had been turned inside out, and the hotel room had been ransacked.

When the authorities interrogated Young, he disclosed that while he had intended to rob Davis of the loan sum, he did not intend to kill him. The beatings Davis' suffered were part of his plan to force him to reveal where the money was. Refusing to believe that he did not have the money, Young had continued to beat Davis' to death. What the authorities discovered on Young when they seized him was not the expected $300 fortune, but a paltry 65 cents. The farmer hadn't yet received his loan.

On April 24, 1910, Young went on trial in the Parry Sound courthouse. There, he was found guilty of manslaughter, and sentenced to life imprisonment in Kingston Penitentiary.

11. Francis Pegahmagabow

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1629

The 23rd Northern Pioneers were the local regiment of Canada's pre-war militia, who had been organized in 1903 upon request by the Department of Militia and Defence. The ranks of the Pioneers were comprised of men coming from the district of Parry Sound and the surrounding towns. They served with distinction in the First World War. One of their number was Francis Pegahmagabow, a 25-year-old Anishnaabe man who became the deadliest sniper of the entire war, credited with killing 378 German soldiers.1

* * *

This was a time when the government only reluctantly allowed First Nations people to enlist. Pegahamagabow, one of the few First Nations people to be allowed to serve in the Canadian Army in the First World War, boldly asserted his indigenous identity amongst his white comrades by raising a decorated wigwam during training at Valcartier, which stuck out amidst the sea of standard tents. It was during the war that the skills he had honed as a youth were wielded with deadly purpose.

The long hours spent shooting and stalking game in Northern Ontario proved ideal training for the battlefield sniper role. On the battlefields of First World War, snipers were the most steel-nerved of fighting men. Unless engaged in attacks or raids, soldiers would shelter below the defensive parapets of the trench. Snipers on the other hand would crawl alone through the muck and filth of the blasted and cratered landscape of no mans land for days at a time, hunting other men.

In this grisly pursuit, Pegahmagabow excelled. An incredible shot, he was known for not only his effectiveness, but also his bravery. It was not unlike him to infiltrate the German lines to find a perfect concealed firing position, firing at them from behind, before slinking back to the safety of Canadian lines.

His loyalty and dedication to the 1st Battalion was without peer -- Pegahmagabow risked his life again and again to save his comrades. He would engage with other elite snipers, always operating under the extremely high likelihood of death. He is credited with 378 kills. The odds against his surviving the war were astronomical, yet somehow he made it through.1

Following the war, Pegahmagabow returned to Parry Island, where he was appointed Chief. He was the most decorated First Nations Canadian in military history.2

12. Fighting Fires

West Parry Sound District Museum 2001.016.1335

1907

This photo from 1907 shows the local fire brigade outside of the fire hall. Designed in 1893 by S.L. White, the fire hall sits on the far side of Market Square. In its early days, the fire hall served as the focal point for social events and holiday celebrations. Its bell, which now sits in Market Square, used to call the curfew for those under 16 until World War II.

* * *

After three children were killed in a fire in 1890, Parry Sound council got serious about the fire question. What was needed was a fire engine, capable of pumping high-pressure water, along with a hall to house it, ladders, water tanks, and a fire bell.

The council voted to rent a Waterous Steam Engine, an engine capable of throwing water within seven minutes of coal being fed. An impressive innovation, it still relied on a dependable source of water for it to work.

The local volunteers were to practice daily with the new engine, so that they might be ready for the inevitable. To better prepare, numerous coal boxes were situated around town so that the engine might have ready access to fuel at any given time and place. They also built platforms to facilitate the operation of the steam pump throughout the east ward and on both sides of Seguin Street.

For many within the town, these measures were still woefully inadequate. One journalist for the Parry Sound North Star lamented, "If there is any crime which can be laid at our doors it is not the crime of undue haste… our zephyr thoughts are caught on another breeze and the need of a fire brigade is relegated to the future until another fire breaks out."1

With the election of Mayor John Galna, fire prevention rose to a top priority. In December 1891, council passed a number of bylaws designed to raise money for the creation of waterworks, so that the town could have access to water mains and fire hydrants. The contractor they had chosen, John H. Armstrong, was less than fastidious in his hydrant designs. Although he had initially promised the creation of a waterworks system that could produce 750 gallons of water per minute, many issues plagued the project. For one, the pipes were not buried deep enough, causing them to freeze and burst in winter.

What ensued was a protracted lawsuit between the township and Armstrong. During the suit, a revolving door of subcontractors were brought in to fix the problems, with little success. The episode sorely tested Parry Sound's finances, and provided a strong argument for the retention of wise legal counsel!

13. The Brunswick Burns

Pictured here is the Brunswick Hotel burning down in 1961. Although promptly rebuilt, the loss of the old building was a blow, as it had been a mainstay in Parry Sound for decades. Its destruction really drove home the importance of having a well-developed fire prevention system. Firefighting is difficult and dangerous work, and having ready access to firefighting resources like pumps, running water, and hoses makes all the difference.

* * *

The fate of Depot Harbour serves as another example. On VJ Day August 15, 1945, the citizens of Parry Sound took to the streets to celebrate the official end of the Second World War. Shortly after dark, the revelers saw a red glow on the western horizon, which gradually swelled into brilliant inferno encompassing half the sky. It came from Depot Harbour, which was then being used as a storage area for millions of pounds of cordite, a highly explosive propellant for artillery shells that was produced at the Defense Industries plant in Nobel. Making matters worse, four million pounds of flammable Australian fleeces were stored there.

The fire started when a store of seasoned lumber, lodged in Depot Harbour's disused grain elevator, caught a spark. The derelict structure was the perfect tinderbox and he flames spread ravenously, burning so hot they turned rails and railcars into "twisted masses of steel."1 Windborne embers blew across the harbour to the freight sheds, where the cordite and wool was stored. It was a perfect storm -- the vast supply of woolens were incredible accelerants for the rapidly expanding inferno. The light cast by the flames was so "bright that you could read a newspaper out on the street" in Parry Sound.1

The local firefighting resources were totally outmatched by the fire and could do little more than watch the fireworks. Many feared an explosion of the cordite, but quick action on the part of a watchman helped confine the blaze to the waterfront -- keeping the cordite out of reach of the flames. One could imagine the level of devastation which might have ensued had the cordite erupted into flame. The fire burned all day and night, and the evacuated population of Depot Harbour was able to return the next day.

Yet after the fire Depot Harbour never recovered. It was soon abandoned, and today only rusted pieces of metal and concrete foundations are evidence of its existence.

Endnotes

2. Building the Railway

1. Hayes, Parry Sound Gateway to Northern Ontario, (Natural Heritage Books, 2005).

3. Booth's Betrayal

1. Hayes, Parry Sound Gateway to Northern Ontario.

2. John Macfie, Parry Sound: Now and Then, (Georgian Bay Beacon Publishing Company Ltd, 1983).

4. The Oddfellows Hall

1. George and Herbert Emery, The Independent Order of Odd Fellows and Sickness Insurance in the United States and Canada, 1860-1929. (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999).

5. Founding Parry Sound

1. Hayes.

6. Trekking to the Store

1. Macfie, Parry Sound: Now and Then.

9. The Baptist Church

1. D. Hammel & L. Ramsay, “The First Baptist Church has served Parry Sound for 130 years," Parry Sound North Star, Mar. 23, 2018.

10. Crime and Punishment

1. Hayes.

11. Francis Pegahmagabow

1. Hayes.

2. Macfie, Parry Sound Old Times

12. Fighting Fires

1. Hayes.

Bibliography

Emery, George & Emery, Herbert. A Young Man's Benefit: The Independent Order of Odd Fellows and Sickness Insurance in the United States and Canada, 1860-1929. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1999.

Hammel, Dougal, and Louise Ramsay, “The First Baptist Church has served Parry Sound for 130 years” ParrySound, https://www.parrysound.com/opinion-story/8346980-the-first-baptist-church-has-served-parry-sound-for-130-years/.

Hayes, Adrian. Parry Sound: Gateway to Northern Ontario. Natural Heritage Books, 2005.

Macfie, John. Parry Sound: Old Times. Hay Press, 1996.

Macfie, John. Parry Sound: Now and Then. Georgian Bay Beacon Publishing Company Ltd, 1983.