Walking Tour

A Nation's Journey

Canada Through Ottawa's Eyes

Alexa Dagan

Library & Archives Canada No. 3194613

For thousands of years, the Ottawa River has been a major artery in the extensive network of waterways that permeates eastern Canada. Indigenous groups first made use of the Ottawa for their extensive trade networks, but by the 1800s, the new frontier town of Bytown used the river as a superhighway for the shipping of lumber. This tour will explore the establishment of the violent, muddy frontier town of Bytown and its humble beginnings as a lumber town through the growth of Ottawa, as officials sought to establish Ottawa as the gleaming capital of an immense and hopeful new nation.

This tour begins at the mouth of the historic Rideau Canal and explores the waterway's role in both early Canada and Bytown, and the unique factors that made Ottawa the first choice for the capital. Then, we cross the Rideau River and stop for a brief moment of reflection at the National War Memorial and the role Canada played in World War I. From there, we wander down the sidewalk gardens and patios of Sparks Street to explore Ottawa's adolescence and troubled growth into a capital. Finally, the tour ends at Parliament Hill where we take in the breathtaking views of the Ottawa River and surrounding cityscape and delve into Canada's slow and careful separation from Britain, the paranoia and icy tensions of the Cold War, and finally, the difficulties of unifying and governing a country with two national languages, dozens of cultural and religious groups, and a geographic size second only to Russia.

1. Founding Bytown

Library & Archives Canada C-011047

1840s

This mid 19th century painting shows what you would have seen standing on this spot in the early days of European settlement. While over a century of development has changed the view somewhat, the mighty Ottawa River and the imposing bluffs of Parliament Hill are just as impressive today as they were in 1826 when the Governor-in-Chief of British North America, Lieutenant Colonel John By, and a crew of invested individuals surveyed the area for a proposed canal.1 The decision to make this spot the entrance to the Rideau Canal would birth a settlement that would eventually become a new nation's capital.

* * *

French fur traders began to use this riverine highway in the 1600s, but it was no easy journey. The Ottawa's swift current and ferocious rapids required careful navigation and frequently forced traders to carry their canoes--portage--over rough sections. Once the fur trade began to wind down, the river began to serve as the primary means of transportation for the logging industry.

As more loggers and a few hardy homesteaders moved into the Ottawa River Valley, the legal rights of the original Algonquin inhabitants were ignored. After the British conquest of Canada in 1759, King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which established government in the territory and also explicitly guaranteed land rights to Indigenous peoples. All land was to be considered Indigenous-owned unless purchased by the crown, or ceded through treaties.

Yet the new European settlers had no intention to honour their end of the bargain. They simply took the land. The Ottawa River Valley was never officially sold or ceded by the Algonquin, and remains within their traditional unceded territory to this very day. Ultimately, the decision of the young settler-colonial society to build its capital on stolen Indigenous land was filled ominous symbolism for the future.

2. A City Divided

Library & Archives Canada No. 3358977

ca. 1900s

This spot offers another spectacular view of Ottawa's natural landscape. Here, the Rideau River swells the waters of the Ottawa as Parliament towers over the city from the river's bluffs. The Ottawa River, being a natural boundary, also runs along the political border between Ontario and Quebec, the two largest and most populous provinces in Canada. From your vantage point in Ottawa, Ontario, you can see the city of Hull, Quebec, on the opposite bank.

While it sounds boring, the moderate compromise is in fact a defining Canadian value. It is rooted in the often fraught coexistence of the Anglophones, and Francophones concentrated in Ontario and Quebec respectively. Most of the work of Confederation was the careful hammering out of compromises between these two groups. The choice of Ottawa as Canada's capital, located as it is right on the border the two territories, then stands as a monument to this spirit of compromise.

* * *

To the politicians of the largely French-speaking Quebec (Lower Canada at the time), Toronto was staunchly Protestant, strongly influenced by the American press, and simply far too British. Kingston was also too Protestant and perilously close to the American border.

As far as the Ontarians (or Upper Canadians) were concerned, Montreal was too violent and unpredictable, its politics strained by bitter cultural conflict. Two major rebellions against British rule by French Canadian radicals in 1837 and 1838 left over 300 dead.1 Moreover, at this time Montreal was the economic centre of the country, and moving the seat of government there would have evoked jealousy from other cities.

Finally, Quebec City was considered to be the symbolic centre of Roman Catholicism and situated too far east to be a practical choice. One Anglophone politician couldn't help but add "Quebec [City], to an Upper Canadian, Is about the most miserable place considerable".2

By contrast, Bytown was a muddy and inconsequential frontier town and had a well-earned reputation for being the toughest town in British North America. Until 1863 it lacked a proper police force and instead depended on a small, volunteer constabulary who struggled to prevent frequent drunken brawls, thefts, and all the other vices characteristic of towns inhabited almost exclusively by young men working dangerous jobs..

The worst was the so-called Shiner's War of the 1830s and 1840s. The "Shiners," rowdy Irish labourers recently left jobless by the completion of the Rideau Canal, terrorized Bytown for almost eight years with assaults, property damage, and petty violence, giving rise to the saying, "Il n’y a pas de Dieu à Bytown" or, "There is no God in Bytown."3

Despite Bytown's reputation, it was also free from much of the jealousies that plagued the other contenders: It had a large population of Catholic, French Canadians, wasn't influential in either Upper or Lower Canada and, with westward expansion appearing increasingly likely, would soon become geographically central.

In 1844, the newspaper, the Kingston Statesmen released a statement advocating for Bytown as the capital: "Let it, [the seat of government in Canada] be taken to Bytown, and we are content, its situation is central, its public grounds are ample, its position unassailable, its climate wholesome, its population loyal, its approach to friends easy, to foes difficult, its fertile land and splendid forest, almost inexhaustible."4

3. The Rideau Canal

1901

Looking down from the bridge towards the Ottawa River you can see the first eight locks of the Rideau Canal. Completed in 1832, this impressive feat of Canadian engineering kickstarted this city's growth. In the 19th Century roads in most of Canada spanned the spectrum from 'muddy rutted tracks' to 'nonexistent.' Moving goods along these roads was prohibitively expensive, if it was possible at all. So the only good way to move goods and people--and armies-- was by water. Canals like this were absolutely crucial to early industrializing economies. This particular canal, however, was built not for prosperity, but for defense. \

* * *

An alternative waterway sufficiently far from the American border was required and the Rideau River fit the bill, though it needed huge investments to be made navigable for the large craft that could move troops and supplies in the event of a war.

Ultimately, the canal's utility in defending the country would never be put to the test, but its construction did lead to the establishment of Bytown at its mouth. Upon completion in 1832, the canal's 200 km length included 24 dams and 47 locks.1 It was one of Canada's first major infrastructure projects.

The canal enabled an economic boom in Bytown, as a huge lumber industry sprang up and grew to dominate the economy. At its peak in 1902, the amount of lumber carried by about 52,000 modern logging semi trucks would be shipped from Ottawa.2

Soon thereafter the industry fell into decline, as did the canal's usefulness. The depletion of the Ottawa Valley's forests, and the opening up of new areas across Canada for logging, spelled the end of Ottawa's days as a lumber town. The last log raft would sail down the Ottawa River in 1904.

As for the Rideau Canal, it enjoyed a short period of importance, but was forever competing with the St. Lawrence shipping route and never quite reached the same level. The canal was expensive, and slowed by its many locks and awkward hours of operation.

As early as 1828 Montreal mechant Simon McGuillivray correctly predicted the canal's fate, "The Rideau Canal, I should think, will never bring down much produce, it is an important improvement in the country with a view to its military defence, but whilst the St. Lawrence is open, and whilst considerable craft can come down the St. Lawrence without impediment, I should think that many of them will never come down through the Rideau Canal." 3

The expansion of the railway and the invention of motor vehicles would cause the Canal to sink even further into redundancy. The last of the cargo barges sailed up the canal in 1920. Since then it has served as a tourist attraction, and a fun trip for pleasure boaters.

4. Wilfrid Laurier

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec P600,S6,D5,P1293

1919

Just over a century ago, on February 22, 1919, over 100,000 spectators strained to catch a glimpse of the funeral procession of one of Canada's most celebrated political figures.1 You can see them here lining the snowy streets to pay homage to the life and legacy of Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister from 1896 to 1911. Laurier presided over the years of Canada's most explosive growth, when a million immigrants settled the West, the country rapidly industrialized, and everything seemed possible. Laurier's optimism reflected the national mood. In 1904 he declared:

“Let me tell you, my fellow countrymen, that all the signs point this way, that the 20th century shall be the century of Canada and Canadian development… For the next 100 years, Canada shall be the star towards which all men who love progress and freedom shall come.”2

* * *

Laurier's long and illustrious career he negotiated some of the thorniest issues of the country's adolescence. This period of Canada's growth, which was characterized by expansion into the prairie provinces was nonetheless fraught with growing pains which would cause deep divisions in the country on more than one occasion.

As in most periods of Canadian history, the largest points of contention centred around the conflict between Francophones and Anglophones and, the former's right to their language, religion, culture, and autonomy. Even as the Francophone minority was struggling against assimilation, Canada was expanding ever westwards following the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Settlement of the prairies and agricultural expansion was one of the great achievements of Laurier's government. During Laurier's fifteen years as Prime Minister, the number of immigrants exploded from 17,000 in 1896 to 331,000 in 1911.3 This vast increase in population, while contributing to the country's growth, nonetheless exacerbated the feelings of marginalization in French-Canadians communities as the large majority of new settlers were not French speaking. In addition to juggling conflicts between Canada's linguistic and religious groups, Laurier was also laying the groundwork for Canada on the international stage in his relationships with both Britain and the United States. While abroad, Laurier continually represented Canada as an proud, autonomous nation and demanded respect from the leaders of both nations in their dealings. Laurier's time in office would see the rise of a national pride and identity that would carry on into World War I.

In 1887, years before his death, Laurier spoke to the legacy he hoped to leave behind, "When the hour of final rest comes, when my eyes close forever, if I may pay myself this tribute, this simple tribute of having contributed to healing a single patriotic wound in the heart of a single one of my compatriots, of having thus advanced, as little as may be, the cause of unity, concord and harmony among the citizens of this country, then I will believe that my life has not been entirely in vain."4

5. Canada Goes to War

Library & Archives Canada No. 3194609

1939

At seventy feet tall, the National War Memorial cuts an impressive figure. Originally unveiled in 1939 by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, the monument was originally dedicated towards those who served in World War I. The sculptor, Vernon March, named his design "The Response," he chose this title and the design, "to perpetuate in this bronze group the people of Canada who went Overseas to the Great War, and to represent them, as we of today saw them, as a record for future generations..."1

* * *

The awe-inspiring size of the memorial is a reminder to every visitor of the staggering loss of life resulting not only from the first World War, but in every subsequent conflict Canada took part in. World War I in particular is remembered for its horrors, memories of squatting in a muddy trench while shells rained down and exploded nearby, or watching as a poisonous green gas crept across a battlefield. The National War Memorial stands to remind us not of only of those whose lives were taken by war, but the experiences of those who lived.2

On the fateful day of August 4, 1914 Britain declared war against Germany. As a Dominion in the British Empire, Canada was automatically at war as well, although not necessarily obligated to fight it. However, public opinion was largely willing if not hugely enthusiastic about supporting Britain in a European war and with a surge of imperial pride, Canada geared up for war. The Great War spanning a total of fifty-one months, would claim the lives of 66,651 of the 600,000 men and women serving in Canada's armed forces.3

Before The Great War, the majority of Canadians were English-speaking and of British descent. As such, many Canadians had a strong loyalty to Britain and considered themselves to be equally Canadian and British. In Ottawa, on the evening of August 4, crowds gathered outside of Chateau Laurier and on Sparks Street celebrating an outpouring of patriotic feeling and singing "God Save the King."3 Similar crowds could be seen on the streets of Toronto and Vancouver, yet communities dominated by French Canadians remained largely quiet.

While many British Canadians celebrated the cause of the war, the majority of French Canadians viewed it as a British war on foreign soil in which Canada had no invested interests. While it was true that many squabbles between the Federal and Provincial governments were suspended and that those in power were united in their contribution to the war effort, The Great War was also hugely divisive. Many French Canadians felt no loyalty to the British Empire or its war, and among the 400,000 German-born immigrants there was little outward display of enthusiasm for a war against their homeland. In fact, one of the largest points of contention during the war was the issue of conscription, which deeply divided the country.

Regardless of the differing levels of support across the country, Canadians served with distinction and incredible bravery in the Great War. Of course, the legendary conflict at Vimy Ridge would have the most lasting effect on the Canadian cultural imagination. The victory at the Vimy Ridge is called one the most decisive victories of first World War and in 1967 Brigadier-General Alexander Ross reflected on the impact of that victory, "It was Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific on parade. I thought then, and I think today, that in those few minutes I witnessed the birth of a nation.” While Canada had long been a nation before Vimy Ridge, this moment in Canadian history was the first time Canada had had a moment of national pride on an international stage.

World War I, while highly divisive in Canadian politics, also served to heighten Canadian patriotism and began to foster in Canadians a desire to grow away from the British Empire. Those who served, and lost their lives in this and future wars would be commemorated in this memorial and in several others both in Canada and worldwide..

6. Becoming a Capital

Library & Archives Canada No. 3400446

1901

At the turn of the last century, when Canada was undergoing the worst of its growing pains as a young nation, Ottawa was also growing into its role as the country's capital. As you can see in this photo of a bustling Sparks Street, Ottawa had come a long way from its roots as a rambunctious logging town. Sparks Street was the first street to be paved in 1895, and it was seen as symbolic of the new era and Ottawa's emergence as a modern city.A colourful newspaper ad published by the R.J Devlin Fur Store gives an idea of how grateful Ottawa's citizens were for this momentous development:

"Take a final look at Sparks St. as it is. This is your last chance to see a panorama of Alpine scenery, the ruins of Pompeii, a section of South Dakota after after a cyclone and about two acres of the slough of despond. You will spear no more frogs in the gutter. You will catch no more mudouts at crossings. For behold, the asphalt cometh."1

* * *

Even as the physical character of the city was changing, the population was as well. The greatest wave of immigrants in Canada's history arrived in this period, helping double the country's population from 3.5 to over 7 million in the 40 years 1871 and 1911.3 While most of the new immigrants headed out further west, Ottawa attracted the bureaucrats, professionals, and politicians required to administer and govern a modern nation state. The capital's population more than quadrupled in that same period, from 21,000 to over 87,000.4

Ottawa also nurtured the growth of several small, diverse communities. Italian and German immigrants made their homes in the city, and by 1911 Ottawa's Jewish community had built three synagogues, a few Hebrew schools, and founded a couple benevolent organizations. Some Chinese settlers found a home in Ottawa, although in smaller numbers than in the Chinatowns of western Canada. Economic depression and world war brought this boom in construction and population to a shuddering to a halt in the 1910s, though when the Centre Block of Parliament burned down in 1916 work was immediately undertaken to rebuild it.

After World War II, efforts to beautify Ottawa continued, with priority given to clearing up congested and unsightly railway lines, and creating green spaces. In 1968, city planners proposed to close Sparks Street to vehicular traffic permanently and make the street into a pedestrian mall, one of the many efforts made by the city government to make Ottawa a city not just for housing the government, but for the enjoyment of residents and tourists alike.

7. Canada's Cold War

Library & Archives Canada No. 4717353

1950s

This provocative artistic rendering produced by the Canada Emergency Measures Organization paints a grim visual of Parliament reduced to a smoking ruin against a backdrop of charred trees and twisted road signs. This troubling scene was meant to impress upon the public the grave danger a nuclear war with the Soviet Union posed to Canada and its institutions.

After the Second World War the world was divided into two armed camps led by the United States and the Soviet Union. The half century long standoff became known as the Cold War, and the nuclear brinkmanship between the two superpowers brought humanity perilously close to catastrophe on more than one occasion. Canada was a founding member of the US-dominated NATO alliance, so if the Cold War ever turned hot then Canada and its seat of government would find themselves squarely in the crosshairs of Soviet bombers and ICBMS.

* * *

This event began a period of extreme suspicion towards communism and the Soviets, but also coincided with a period of continuous immigration that would forever change the character of Canada's population. Between 1946 and 1962 over 2.1 million immigrants would arrive in Canada, a country which had only 11.5 million people in 1941.1 Many of these new arrivals were European refugees, displaced persons, or simply those who were leaving their war-torn countries for better opportunities across the Atlantic. These new arrivals from Europe were often greeted with sympathy, with Canadian newspapers such as the Toronto Star publishing harrowing accounts of refugees escaping with their lives. One such story published in Mcleans' in 1953 told of one family's escape from behind the Iron Curtain from Vienna to Paris through swamps, woods, and barbed wire fences while all while barely evading patrols. The title of the article was simple, but effective,"We are escaping bad men in the forest, and if you cry, they will get us," a mother's warning intended to shush her young children during a particularly close call.2

However, tales of bravery and hardship such as these were not enough to quell the feelings of suspicion and distrust many Canadians had of these new arrivals. Even while newspapers and magazines were publishing Iron Curtain escape tales celebrating the heroism of new arrivals, the RCMP worried that Soviet spies might lurk undetected among the families now entering the country and urged Ottawa to tighten security around immigration.

Throughout the mid-20th century, the Cold War continued to unsettle both Canadian citizens and the Federal government as the threat of nuclear war loomed. Canada would join NATO and followed the United States into the Korean War, yet simultaneously mediated in peacekeeping missions in areas divided by communist conflicts, and criticised the US for their actions against communism in other countries. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union would effectively end the Cold War in Canada in 1991, and the illustration of Parliament in ruins would remain merely a picture of a future that never came to pass.

8. Journey to Independence

Library & Archives Canada No. 4297693

This photo, taken in 1959 shows Queen Elizabeth inspecting the parliament guards on her second visit to Canada. Since her ascension to the throne in 1952, Queen Elizabeth has visited Canada on official royal visits twenty-two times, and these visits are always met with popular support and large crowds. By Queen Elizabeth's visit in 1959, Canada was independent in almost every regard. However, Canada's journey to independence is often misunderstood as having been fully achieved on the day of the Constitution Act, which united the three colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada (soon to be split into Ontario and Quebec), into the Dominion of Canada on July 1st, 1867.

* * *

Canada's relationship with Britain began to shift during the interwar period. Having proved itself as a nation during World War I, Canada further asserted its position as a fully-fledged nation by signing onto the League of Nations in 1919, and began to negotiate other international relationships, especially concerning the United States, without Britain's participation. Canada was growing up. However, it wasn't until the Statute of Westminster in 1931 that Canada would gain almost full legal autonomy from Britain. This act, which concerned all of Britain's Dominions, gave legislative independence not only to Canada, but to New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa as well.

However, there remained one crucial limit to Canada's new legal autonomy, the ability to amend, appeal, or alter Canada's Constitution would remain under control of British Parliament, an exception agreed upon by Canada's federal and provincial governments. The business of full Canadian Independence would finally be settled in 1982 with the Constitution Act, which enshrined the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the Constitution and allowed Canadians to amend their own constitution without Britain's supervision.

9. An Excess of Geography

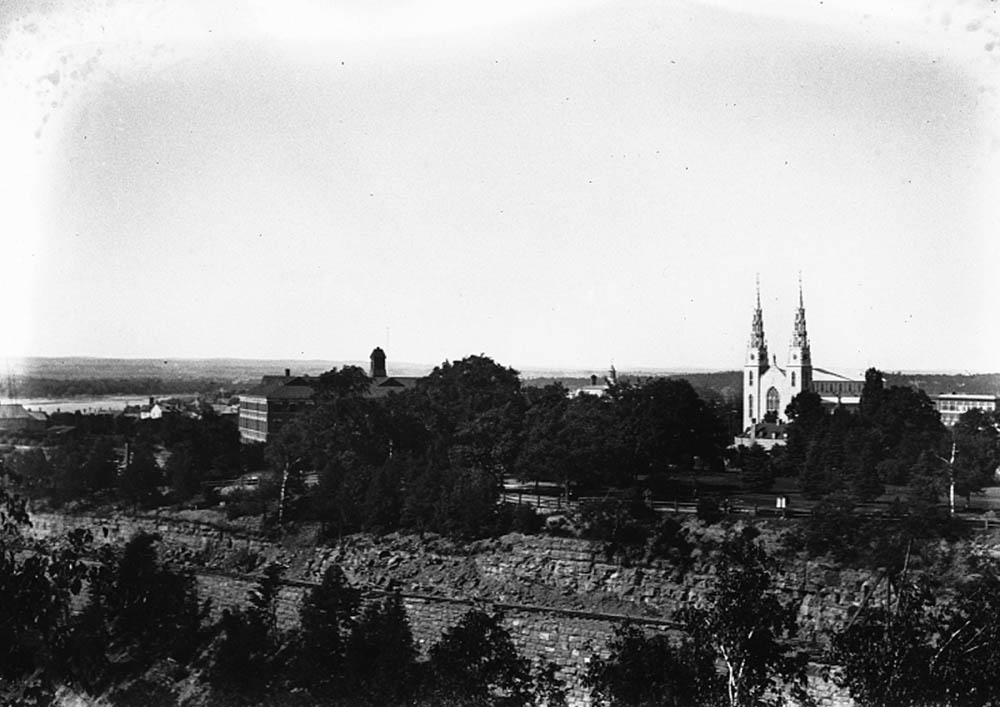

1900

This spot, on the edge of parliament hill provides an outstanding viewpoint of some of Ottawa's most iconic structures. The Fairmont Chateau Laurier, the Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica, the first 8 locks of The Rideau Canal, and the Alexandra Bridge. However, all of these grand structures, with their rich histories and backstories are still not the most impressive man-made structures visible from this spot. Directly below you, almost on the banks of the Ottawa River, is a section of the Trans-Canada Trail.

* * *

Former Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King is quoted as saying, "if some countries have too much history, we have too much geography" in a speech to the House of Commons in 1936.2 Geography isn't the only challenge though, from coast to coast, Canadians often must balance a regional identity with a national one. An Albertan community whose economy is based on the oil sands has different needs than a small coastal town dependent on ecotourism, or a northern First Nations community, and groups such as these often come into direct conflict with one another. Connecting the country on a geographical scale required the federal government to build thousands of kilometers of infrastructure, namely railroads, highways, bridges, and tunnels, but connecting such a diverse collection of people has proved far more challenging.

Parliament Hill, as the seat of government, has long been the site of protests and rallies as various groups fight for visibility, support and, in many cases, direct government action. Some of the most important protests in Canadian history have occurred on Parliament Hill. In 1971, around one hundred people assembled here to fight for gay rights in the first large-scale public protest on LGBT rights in Canadian history. In 1982, labour unions assembled in the single largest demonstration on Parliament Hill in Canadian History to protest high interest rates and unemployment.

These protests are a testament to the diversity of the Canadian people, who can differ in every possible regard, but are united by a unique, underlying Canadian identity which sets us apart.

10. The Long Journey

1900

The last photo on this tour shows the view from the top of Parliament Hill as it would have looked in 1900. The Ottawa River still commands respect, as its waters churn in the rapids below the hill, but the surrounding landscape is busier now with glass and concrete buildings dominating the skyline and thousands of cars crossing the Alexandra Bridge every day. Ottawa has grown since its rough beginnings as Bytown, becoming a beautiful and polished capital city, and its growth mirrors that of the nation it represents.

* * *

Endnotes

1. Founding Bytown

1. Robert Haig, Ottawa, City of the Big Ears: The Intimate, Living Story of a City and a Capital (Ottawa: Haig and Haig Publishing Co., 1975), 34.

2. John Taylor, "Ottawa" The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 2017, online.

2. A City Divided

1. Philip A. Buckner, Rebellion in Lower Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. July 24, 2013, online.

2. David B. Knight,Choosing Canada's Capital: Conflict Resolution in a Parliamentary System (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1991), 30.

3. James Powell, Today In Ottawa's History, "The Shiner's War," August 4, 2018, online.

4. Haig, 111.

3. The Rideau Canal

1. Haig, 79.

2. Haig, 97.

3. John H. Taylor, Ottawa: An Illustrated History (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, Publishers and Canadian Museum of Civilization, National Museums of Canada, 1986), 23.

4. Wilfrid Laurier

1. Andre Pratte, Extraordinary Canadians: Wilfred Laurier (Toronto: Penguin Publishing, 2011), location 2080, Ebook.

2. Wilson-Smith, Anthony. "Canada's Century: Wilfrid Laurier's Bold Prediction," November 15, 2016., online.

3. Pratte, Location 1656

4. Pratte, Location 2074.

5. Canada Goes to War

1. "National War Memorial" Veteran's Affairs Canada, Feb. 18, 2019, online.

2. Haig, 197.

3. Hair, 178.

4. Brian Douglas Tennyson, Canada's Great War, 1914 - 1918: How Canada Helped Save the British Empire and Became a North American Nation, (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014), 19.

6. Becoming a Capital

1.Haig, 162.

7. Canada's Cold War

1. Franca Iacovetta, Gatekeepers: Reshaping Immigrant Lives in Cold War Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2006), 10.

2. Iacovetta, 40.

9. An Excess of Geography

1. Trans-Canada Trail, "The Great Trail," online.

2. "Geography," Statistics Canada, last modified 2009, online.