Walking Tour

Twin Highway Camps

Forced Labour at Mara Lake

Andrew Farris

In 1915, two forced labour camps were built along the eastern shore of Mara Lake to house Austro-Hungarian internees as they built the road connecting Sicamous to the North Okanagan. It has since been upgraded and expanded over the last century into the highway we drive today.

To build it, these internees blasted a path from the mountainside along the lake's edge and graded a rough road--all without the use of heavy equipment. When they finished the day's hard labour they slept in rudimentary bunkhouses, ate bland and nutritionally deficient meals, and tried to pass the time. They suffered innumerable indignities throughout. They were abused by the guards, forced to work in frigid winter conditions with only summer clothing, and were deprived of all their rights by a government keen to exploit their labour to maximum effect.

When the road was completed in 1917 these camps were closed. The remaining internees were paroled or dispatched to other camps to repeat their ordeal.

Almost all of the internees were people who had emigrated to Canada at the invitation of the Canadian government. Nevertheless, when the war began they were interned solely due to their country of origin. The government knew they posed no threat to national security, but they did not care. The public took little interest in the awful conditions in these camps and it didn’t generate much in the way of outcry. After the war their story was lost for decades.

In this tour we will see how the camps came to be, what life was like for the internees, and how this gross violation of the rights of immigrants was allowed to happen.

Route

This tour has two legs and requires driving along Highway 97A. A car is highly recommended. It can also be biked by experienced cyclists.

The first leg begins just south of Sicamous at Two Mile Point, where Two Mile Road intersects with Highway 97A. The site is now home to Sicamous Houseboats.

To reach the second leg of the tour and Six Mile Camp, you can drive south on Highway 97A for 6.4 kilometres south to Swansea Point. Turn right onto Swansea Point Road, and drive to the end, where you will turn left onto Swanshore Road. Continue along the curving road until you see a beach access on your right. From here you can walk along the beach in front of Hummingbird Beach Resort to see the former site of Six Mile Camp.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Settling Mara Lake

Greater Vernon Museum & Archives 936

ca. 1915

The tour begins in the parking lot of Sicamous Houseboats at this location.

This view of the internment camp at Two Mile Point was taken from the mountainside overlooking the lake. Looking up the lake into the distance, you can see a thin strip has been cut down on the water's edge--the road built by the internees. The camp itself is a simple affair: with 8 bunkhouses, quarters for camp guards, a few support buildings and a boathouse. Looking at it, you can tell that this camp was not built for comfort - especially during the harsh winters.

This was the second of the two road-building camps on Mara Lake. Two Mile Point was used in winter, while Six Mile Point to the south (now known as Swansea Point) was used during the summer.

* * *

The arrival of the railway changed everything. Settlers began pouring in, and Sicamous quickly grew into a town.

In the years that followed, a huge wave of Eastern European immigrants flowed into Canada. Many were from the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire. Though their passports usually said "Austrian," they actually comprised over a dozen different nationalities. They were Polish, Czech, Russian, Romanian, Slovakian, Croat, and Ukrainian, to name a few. The Ukrainians were the largest group, and to make matters even more confusing, the Canadian authorities didn't use the term Ukrainian but instead a variety of other terms: Galician, Bukovynian, Ruthene, Rusyn, Ruthenian or even Greek Catholic. This makes estimating the exact numbers of Ukrainians difficult, but it is thought that by 1914, about 170,000 called Canada home.1

Most had come to Canada for free land promised them if they homesteaded on the prairies. Homesteading, however, was incredibly challenging. It also required some money to get started. Unfortunately, many of these settlers had spent what little money they had just getting to Canada.

To raise the funds they needed to get established, or to survive the seasons between planting and harvest, many turned to seasonal labour. This brought them further west, into the mountains of British Columbia. For young men there was plenty of work in lumber camps, coal mines, and on the railway.

By 1914 thousands of "Austrian" men worked across the province, building new lives on the Canadian frontier. Few could have imagined that a chain of events started in the empire they'd left behind would soon propel them into a life of imprisonment and forced labour in this frigid camp.

2. The Road to Mara Lake

Library and Archives Canada 3550144

1915-1918

In this wintry scene at the Two Mile Camp, several camp buildings are visible under a deep layer of snow. On the left side of the photo, a few figures are visible in the distance. They may have been clearing snow, chopping wood for fires--common duties for the internees--or even taking a moment in the cold to stretch their legs outside the cramped camp buildings.

It must have been a shocking and bewildering experience for the young men swept up by the police and dispatched to this icy "concentration camp" because of a war an ocean away that they had no interest in.1 A November 1914 article in the Morning Albertan remarked apparently without irony that "it comes as a great surprise to Austrians to learn that they are enemies of the British Empire." The article quotes one of the men saying ""I don’t want to be arrested. I like this country very well and do not want to go away or make trouble and don’t see why I should be arrested."2

Today we should ask the same question.

* * *

At the same time, attention immediately fell on the hundreds of thousands of people who had immigrated to Canada from lands controlled by the Central Powers. The War Measures Act officially designated all immigrants from these countries 'enemy aliens'. The press published hysterical reports of foiled sabotage attempts on Canadian soil, captures of spies, and debated the likelihood of some kind of invasion of Canada. We know today that all these claims were entirely bogus, and the Central Powers had practically no capacity to cause mischief within Canada.

Nevertheless, the first main effect of this hysteria was that in an apparent fit of "patriotic zeal," many large employers began firing all those deemed 'enemy aliens' en masse.3

As the historian Kassandra Luciuk notes, it is probably not a coincidence that at many coal mines across Canada, the first to be fired were members of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Party of Canada, which was one of the most active organizations fighting for better rights and conditions for the immigrant working class. The war, as she put it, provided a useful pretext for employers to rid themselves of their most troublesome workers, and "cleav[e] off one of the most vulnerable pieces of the organized left."4

The next step was the fateful Order in Council in October 1914. It clarified that people classified as 'enemy aliens' were forbidden from leaving the country, and those "who lacked the means to remain in the country were to be interned and put to work."5

The groundwork had been laid not just to arbitrarily detain thousands of civilians for an indeterminate length of time, but to compel them to do forced labour.

3. Not So Divided Loyalties

Enderby & District Museum Society 4251

1915-1917

Here we see several men, at least one guard, and perhaps some internees posing for a photo in front of a dilapidated hut at the Two Mile Camp.

The legal status of the internees was complicated by the fact that most were civilians, and many were naturalized Canadian citizens. Many had little sympathy for the Central Powers, and this was especially true of the many non-German nationalities of the Habsburg Empire. They'd left behind the autocratic Dual Monarchy, and now found themselves fired from their jobs, harassed by police, and robbed of their possessions. Some were herded into internment camps.

This was done to Ukrainians and others "for only one reason," read an open letter by a group of Ukrainian Canadian newspaper editors: "that they were so unhappy as to be born into Austrian bondage."1

* * *

Thousands still had wives and children back in the Dual Monarchy--one report in the Winnipeg Free Press found 43% of registered 'enemy aliens' in the region had wives in Europe who survived on remittances sent by their husbands in Canada.3 Even if these men had money to send home, they were prevented from doing so. What was to be the fate of their families? That was not Canada's concern.

Penniless, jobless, demonised by the press, and forbidden from leaving the country, these men were forced into an impossible situation. In the fall of 1914, an article in the Victoria Daily Colonist estimated that there might be between 50,000 and 100,000 such 'enemy aliens' living on the streets of Canadian cities by the winter.4

Though it might seem like a cruel joke, from the government's point of view, interning these men against their will was an act of mercy: They would be provided food and board, and an eye could be kept on them until the war was over.

The Justice Minister speaking to the House of Commons in 1918 made a revealing admission:

Quite a number of them were interned more largely under the inspiration of the sentiment of compassion, if I may use the expression, than because of hostility. At that time, when the labour market was glutted, and there was a natural disposition to give the preference in the matter of employment to our own people, thousands of these aliens were starving in some of our cities... In many instances we interned these people because we felt that, saying to them "You shall not leave the country," we were not entitled to say, "You shall starve within the country."... We found that the sentiment of every man who came into contact with the Austrian who was interned was that he was absolutely not dangerous.5

The government's mental gymnastics to justify internment had eerie similarities to the creation of the reservation system for Indigenous people decades before.

First, the government destroyed the lives and livelihoods of a marginalized population. Then, once they were helpless and destitute, the government would show them “compassion” by herding them into protective custody where they could be monitored and controlled. This 'compassion' wasn't free, so it was only fair they be forced to work.

If any violence was inflicted upon them, or if any died or went mad in the process, then that was the fault of an overzealous camp commandant or guard--or of the victims themselves. It was not the result of official government policy, which was, after all, well-meaning.

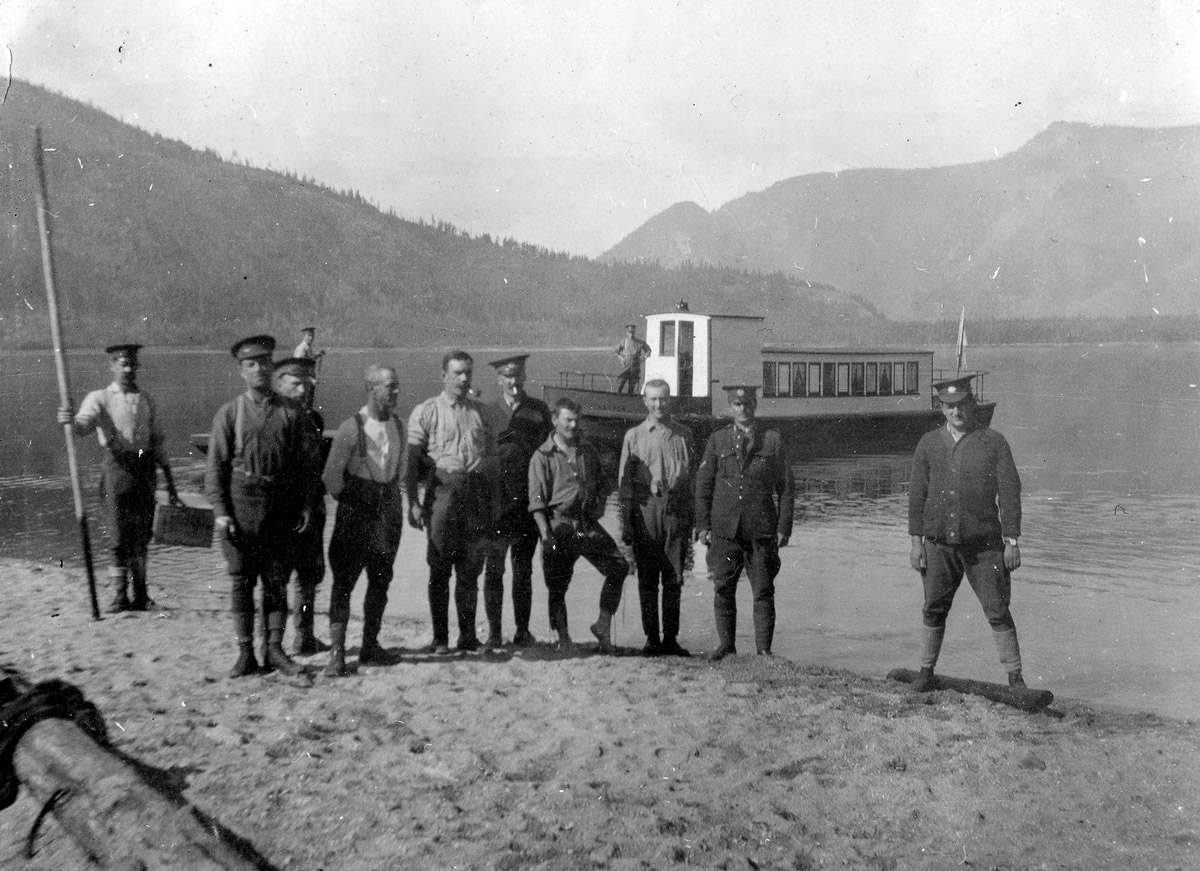

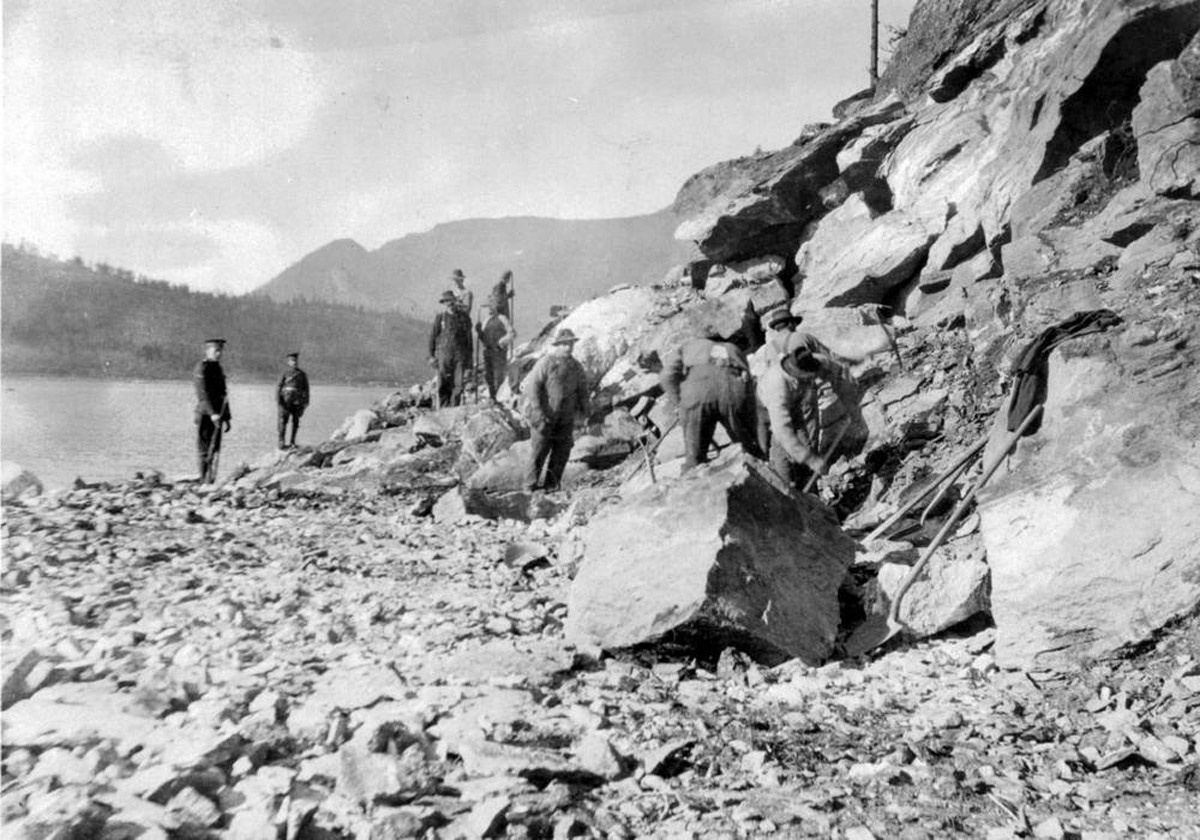

4. Forced Labour

1915-1917

A group of camp guards stand for a photo on the beach at Two Mile Camp. Behind them is the ferry used to shuttle people and supplies up and down the lake. These men were there to prevent any of the internees from escaping as they carved the highway from the mountainside.

The federal government was only too happy to let local authorities put the 'enemy aliens' to work. Imprisoning thousands of civilians was expensive, and at that moment much of Canada's workforce was fighting and dying in the trenches.

There was the awkward question of whether imprisoning and then forcing thousands of civilians to carry out forced labour was a violation of international law (the Hague Conventions were a little vague on this subject). But, as historian Bohdan S. Kordan writes, by virtue of "being able-bodied, they were subject to conscription, which meant they were also potential combatants, to which the laws of war would apply."1

The provincial governments worked out a deal with the military authorities, and began accepting project bids.

A proposal from the settlement of Mara caught the eye of BC's Minister for Public Works.

* * *

Other communities, like Victoria, saw these forced labour camps as a dumping ground for their own unemployed 'enemy aliens', and loudly demanded that all of them should be rounded up and sent away to remote imprisonment. Few apparently had quibbles with the wholesale violation of civil liberties and human rights this entailed.

British Columbia's Minister of Public Works pored over many submissions, and one from Mara, at the south end of Mara Lake, caught his eye. They wanted to build a road between Mara and Sicamous, connecting the Okanagan with the North Shuswap.

As it happened, Minister Taylor was from Mara. So it wasn't a surprise when he immediately approved the proposal, writing that he was, "extremely anxious to see this work undertaken as well as the completion of the road from Taft to Clanwilliam, thereby giving a direct road connection between Revelstoke and Vernon and all points in the Okanagan and Similkameen."3

The Mara Lake internment camp was established just two weeks later, on June 2, 1915. The two road-building camps would remain open for just over two years.

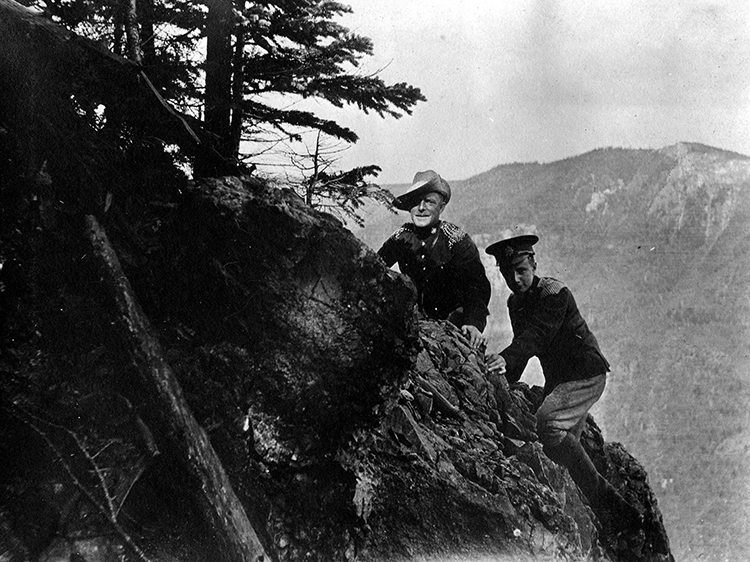

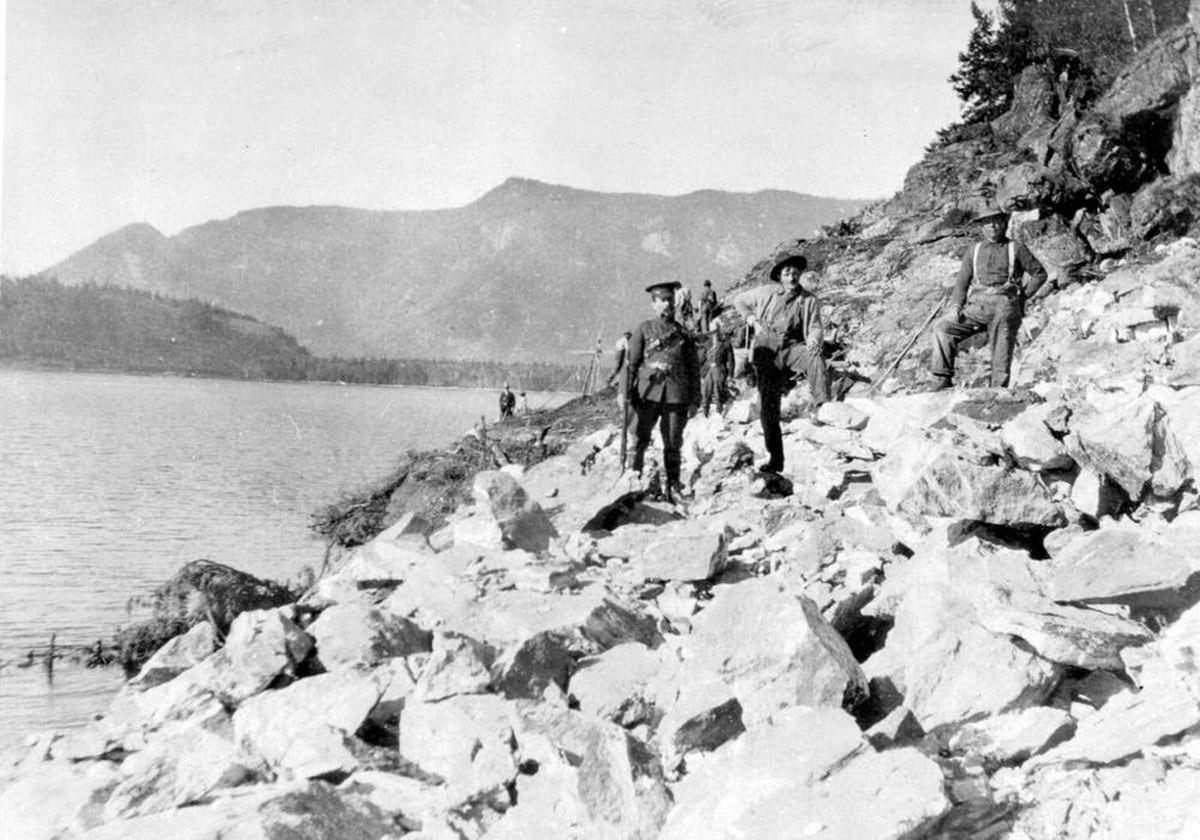

5. Building the Road

Okanagan Archive Trust Society

ca. 1915

A group of men are enjoying a respite from work as they lounge on a jetty on the lake. The military caps indicate that many of them are camp guards, and it is unclear if these are all guards or there are internees amongst them.

These men appear to be having a nice summer day on the lake, and the photo doesn't tell the true story of the back-breaking labour the internees were forced to undertake at gunpoint.

* * *

As the proposal for the Mara Lake road was being approved by Minister Taylor, the citizens of Mara noted that some of the internees working at the Monashee camp had mining experience, which would be useful for such an undertaking.2 Thus, in July 1915 200 internees were transferred from Monashee to begin construction of the Mara Lake road.

Here is a sequence of photos that give one a sense of the huge challenge cutting this road by hand from the stone would have been.

The operation was organized by the provincial government after an agreement with the military authorities. The military would guard the prisoners and force them to work, while the province would supply the tools, explosives, horses, supplies, and prisoners' pay.

Pinching every penny was the priority. and the provincial government audited the finances of the project obsessively, cutting costs at every conceivable point, and insisting on following a dangerously quick timetable. As Kordan writes, "The most important factor determining the value of the camps was whether there was a net benefit. They had to be useful, efficient, and viable."3

The main efficiency that was gained was in the pay of the labourers. They were paid $0.25 a day, about 1/14th of what they could expect to make under normal conditions.4

Further savings could be made by reducing the quality and quantity of food provided to the internees. On paper, the allotted daily ration for an internee was 2,600 calories, though given the haphazard supply situation, historians have good reason to believe this benchmark was rarely met. Even if it was enough food, the government's own policy said 3,000 calories were required to sustain a man labouring.

Compounding this insufficient caloric intake, corners were routinely cut on the quality of the food "and substitutions were routinely made," notes Kordan. "Unleavened flour or pancake substituted for bread, fermented cabbage for vegetables, and rice or rolled oats for meat."5

The province and the military bickered over who was to clothe the internees, with the result that the internees were forced to work--even in wintertime--in boots that were disintegrating, and thin socks that lasted no time at all.

Nevertheless, from the outset progress on the road was swift. The government noted with satisfaction that between September and November 1915 the internees succeeded in blasting, clearing, grubbing (extracting all roots), and grading, a five kilometre stretch of the road. They also built eight culverts and a bridge. Adding in salaries, supply, and equipment expenses, the total cost of this stretch came to $5,963.98, or around $130,000 today. Quite the bargain!

Kordan wryly noted the "significant saving [were] because of the nature of the labour."6

6. The Guards

1917

The photo above shows soldiers of the Rocky Mountain Rangers preparing to disembark from one of the ferries that transported guards and internees around Mara Lake. Behind the wheel is pilot Maurice Gillis, who ran the supply boat for both Two and Six Mile Camp. The Rangers were founded in 1908, around the same time that thousands of Ukrainians were immigrating to Canada.

The soldiers and the internees experienced the war from very different perspectives, but they did have one thing in common: neither wanted to be stuck in camp while war raged in Europe.

* * *

Many of the guards felt ashamed of their assignment. They had enlisted to earn glory at the front fighting for King and Empire. There was no glory to be found guarding 'enemy aliens'--most of whom were civilians.

Many of the guards came to deeply resent their charges, and this contributed to a camp culture of arbitrary, disrespectful, and even violent abuse. Commanding officers at camp frequently ignored or condoned many of the punishments guards routinely inflict on internees for infractions such as refusing to work. beatings, pistol whippings, bayonetting, solitary confinement, and dietary restrictions were reported from camps across Canada.

Major-General William Otter, commander of internment operations, admitted as such in a letter: "The various complaints... as to the rough conduct of the guards I fear is not altogether without reason, a fact much to be regretted, and, I am sorry to say, by no means an uncommon occurrence at other Stations."1

He was particularly offended by one type of punishment that was reported in the Lethbridge camp, a type of torture known as strappado. This consisted of handcuffing a prisoner's hands either behind their back or above their head, then hanging them by the hands until their toes were barely touching the ground. At Banff, there is evidence that internees were dragged through a river against the current as punishment for offences. Elsewhere there are reports of prisoners being physically crucified, that is, tied spread-eagled to a wagon-wheel and left there.2

We have fairly limited records from Mara Lake, but there is some evidence to suggest that severe physical punishment may have been less common than at other camps. This wasn't necessarily seen as a good thing by the road construction superintendent R. Bruhn, as he felt it meant the work fell behind schedule.3

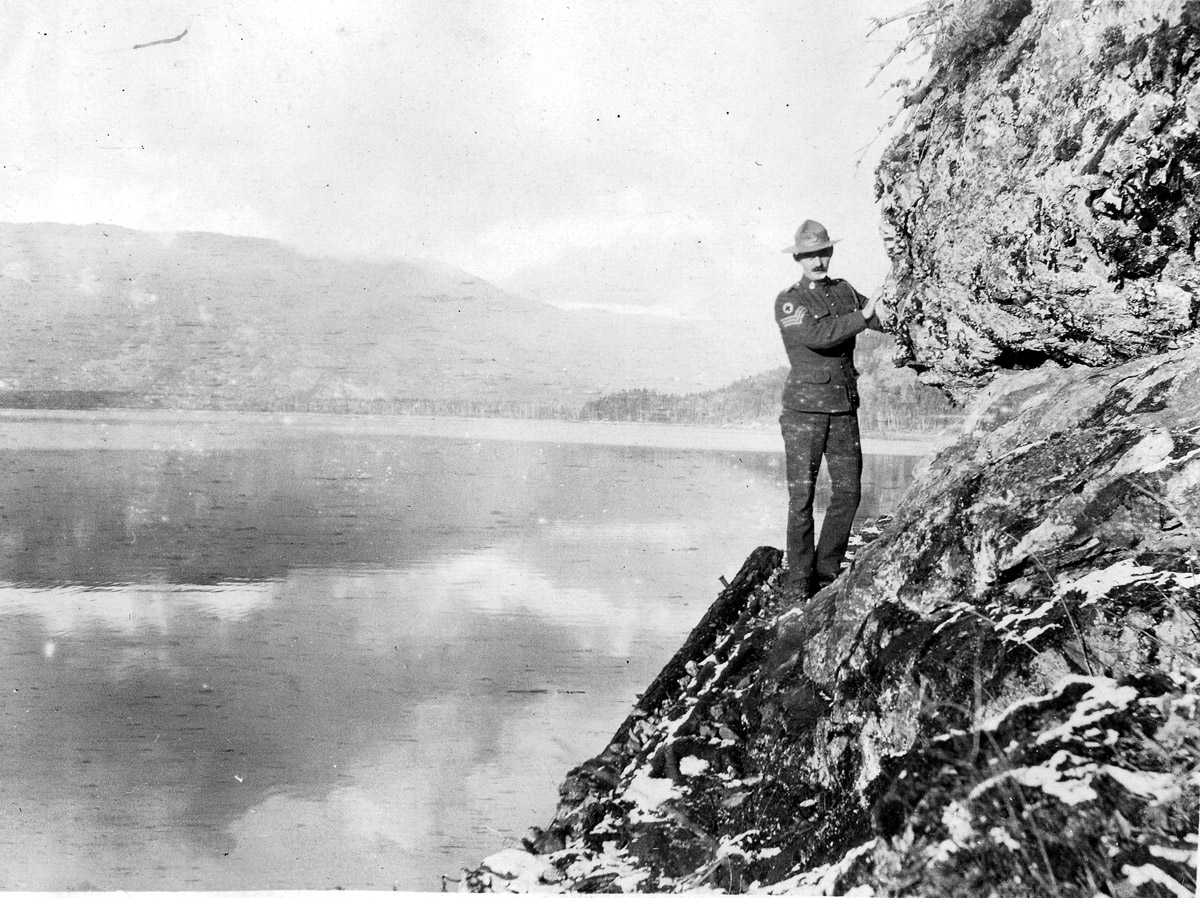

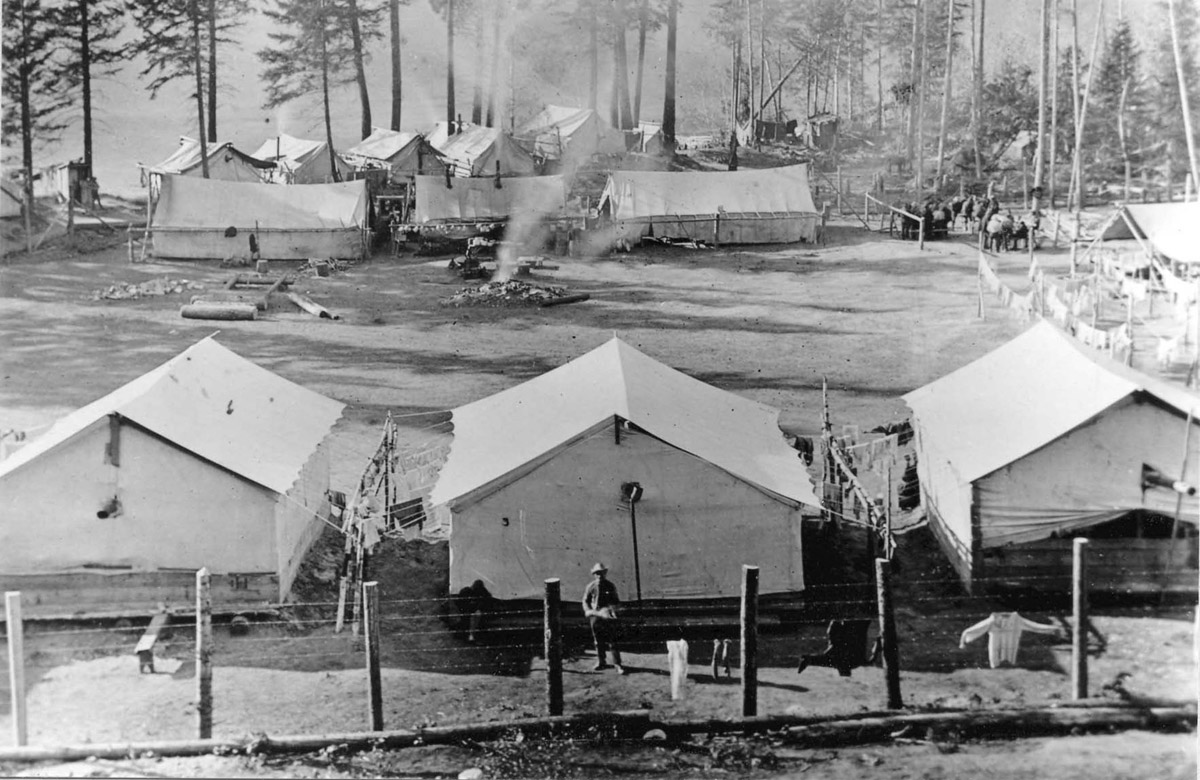

7. Facing the Elements

Library and Archives Canada 3550134

1915-1917

In this photo, several of the buildings at Two Mile Camp are visible under a deep layer of snow. The buildings are all rough, simple structures, some are made out of cutn logs with thin roofs.

During winter minimal provision was made for the care and comfort of the internees. Even when several feet of snow blanketed the ground they were expected to work in the same pair of clothes they wore during the summer. A hard-driving construction superintendent and a company of heavily armed guards urged them forward in their back-breaking toil.

Conditions in summer were better, but still presented great challenges. Compare this photo to the photos of Six Mile Camp, which we will be visiting next. Six Mile Camp was the summer camp, where the bunkhouses were little better than tents, roofed only with tarps. Even in the summer these structures would have been cool at night, and likely full of mosquitos and black flies.

* * *

The winter of 1915 at Mara Lake was an especially cold one and in December and January, Bruhn complained that very little work was done because of the poor quality clothing provided to the internees.

Bruhn framed this issue in financial terms:

if General Otter, in giving this instruction, is looking at this matter from a financial standpoint, I consider this point very poorly taken, as one pair of good lumberman's socks will last all winter when two pair of the socks now provided are only good for a very short time. With the socks now in use, it is impossible to keep the snow out of the shoes and rubbers, causing the men's feet to be cold and wet. This again causes dissatisfaction; it is impossible to get the men to work as they should and the cost of a pair of suitable socks is lost in a few days' work.1

He bemoaned the fact that the guards were reluctant to use "sterner" methods to force the prisoners to work and enforce discipline.

The situation was resolved when a group of internees were transferred to another camp, reducing the internee to guard ratio, but also slowing down the work.

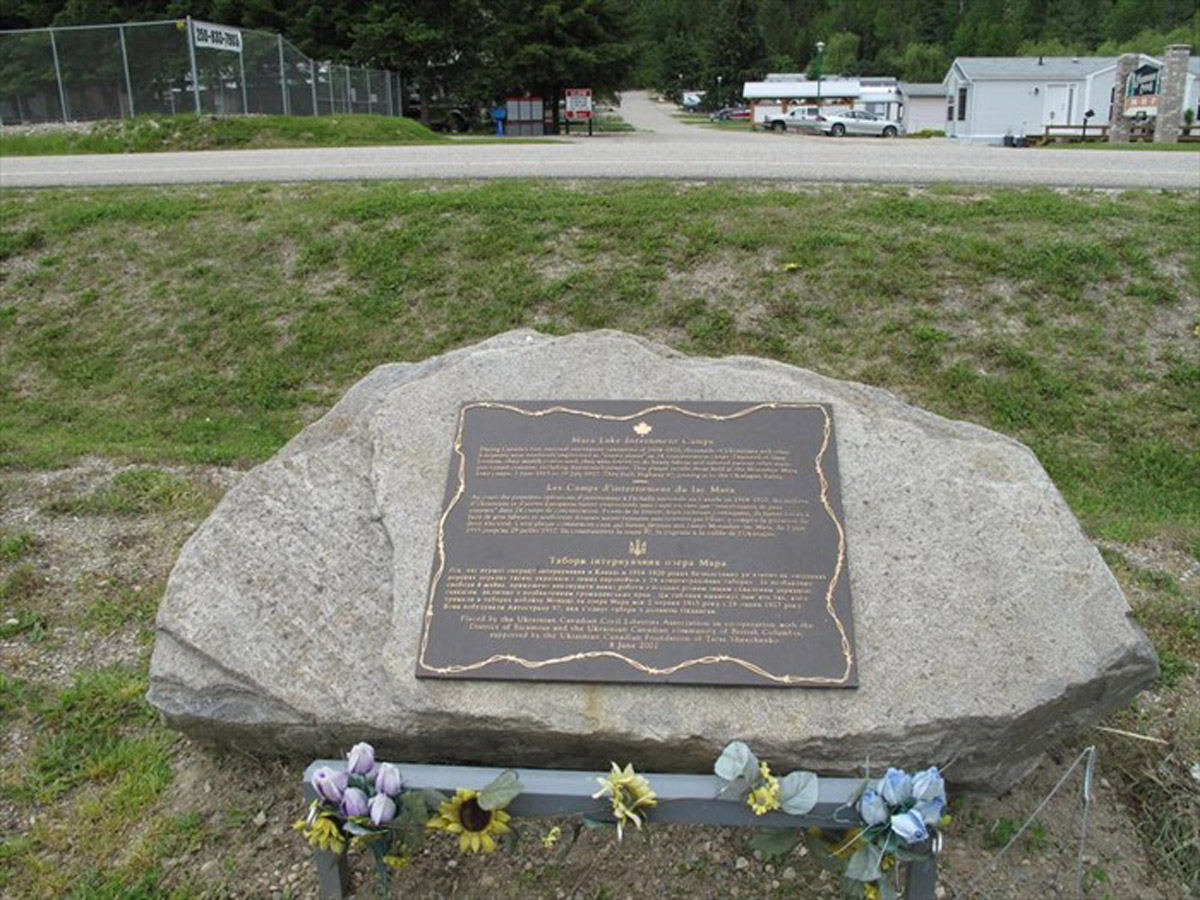

As you leave this site and drive south to Six Mile Camp, you can take a quick stop to see a plaque erected by the Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund that honours the memories of the internees.

To visit the plaque, take the first right onto Wolfe Road while driving south, and then another right where you can see the stone marker just beside the highway.

8. Six Mile Camp

Library and Archives Canada 3379222

ca. 1916

To reach this next stop you must drive or cycle down to Swansea Point. Drive south on Highway 97A for6.4 kilometres. Turn right onto Swansea Point Road and drive to the end, where you will turn left onto Swanshore Road. Continue along the curving road until you see a beach access on your right.

This map marker is located at the beach access.

This is an overhead view of the Six Mile Camp taken from the mountain overlooking the lake. You can see the camp in the foreground at the right, which consists of a small collection of huts in the clearing now occupied by the Hummingbird Beach Resort.

* * *

When the Six Mile Camp opened, many internees who were previously held at the Monashee camp were relocated here. Monashee had closed after only a month due to the trouble supplying and accessing the camp, and the internees were sent either to Mara Lake or the new camp at Edgewood. Unfortunately, not a lot is known about the Mara Lake camps.

Researching the First World War internment camps more generally is challenging for a few reasons.

For the survivors, the memories of their time in camps were unpleasant, violent, and shameful; many simply wanted to forget their time in the camps. Family members and descendents of internees report that they often never knew their parent or grandparent was interned, or, if they did, they never spoke of it.

There were also prevailing attitudes of the time. The widespread prejudice towards the so-called enemy aliens persisted long after the war, and the fear of 'enemy aliens' working with the Central Powers transformed into fear of them working with the Bolsheviks in Russia. As Herbert Clements, a Member of Parliament from Ontario told the House of Commons in 1919:

I say unhesitatingly that every enemy alien who was interned during the war is today just as much an enemy as he was during the war, and I demand of this Government that each and every alien in this dominion should be deported at the earliest opportunity. Cattle ships are good enough for them.1

For the Ukrainians, Poles, Romanians, Germans, and all the other nationalities who were persecuted, it is entirely understandable they'd rather keep their heads down than publicly seek attention and redress. They'd seen how quickly a country that had invited them in could suddenly turn on them.

So, as one survivor wrote, "Memories of the camp gradually began to fade away [but] one could never really forget."2

As the decades wore on, many of the survivors passed away without ever telling their stories. The decision by the National Archives to destroy all internment records in 1954 further handicapped any researchers hoping to uncover this important story.

This means today researchers and descendents are left with many questions about how the internees felt about and experienced internment.

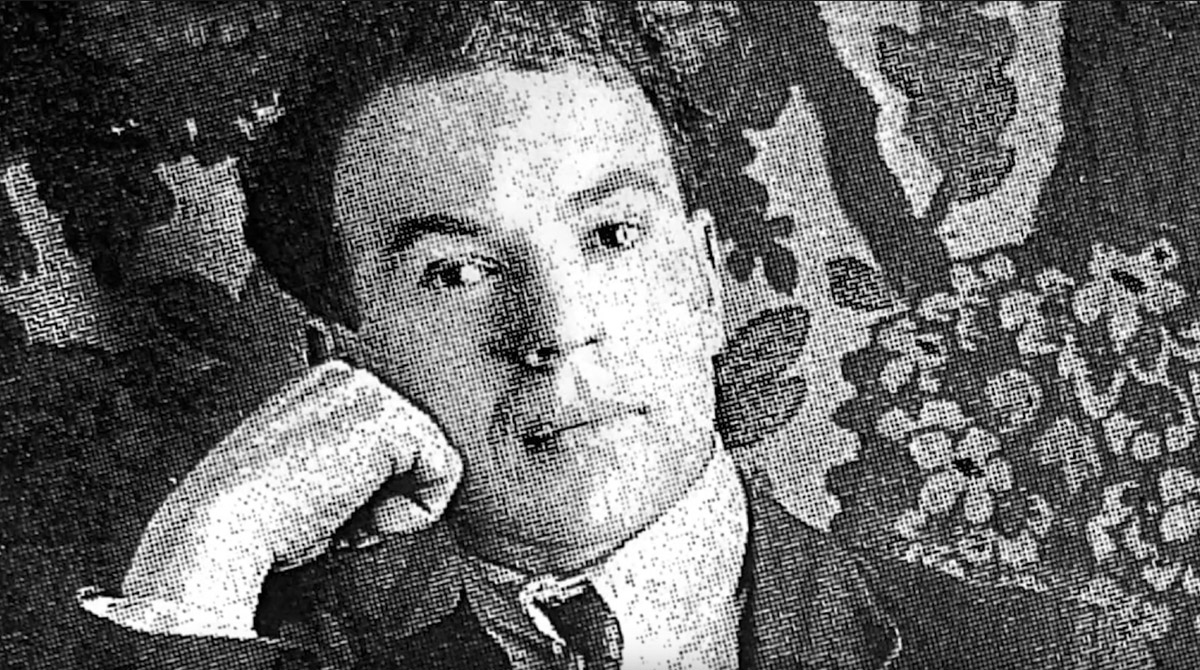

9. Vasyl Doskoch

Enderby & District Museum 4258

1915-1917

You may need to cross a narrow stream to reach the beach where the camp was located. Please use caution when crossing the stream, and only do so if it is safe.

A group of internees sitting on boats at the beach in front of Six Mile Camp during a moment of down time. Finding out more about these men, who they were, what their lives were like, and what happened to them is an immensely challenging task. The eyewitness stories have come down to us almost exclusively through a handful of individuals who shared their stories with their children and grandchildren later in life. One of these stories belonged to Vasyl Doskoch.

* * *

In a recent interview Anne Sadelain, the daughter of internee Vasyl Doskoch, shared some memories of her father. Doskoch was interned for five years in five different camps, including Morrissey, Monashee, Mara Lake, Vernon, and eventually Kapuskasing. Sadelaine recalled the devastating impact the experience had upon him.

It was never a surprise what had happened. It seems to me I've always known that there was something in his background that was negative - bad. But as we grew older we started to ask questions. When I started to hear more and look into what had happened in the camps I became quite outraged. Many of them did not speak a word of English, and the camps were terrible places for them. There was a lot of illness. There was mental illness. People committed suicide. Everything they wrote was censored and it would take weeks for them to get a censor in and so their communication with their family was often nil - and these boys needed help. The food at the internment camps was always terrible, and their clothing was not good for the weather, and often their shoes were completely worn out. My father spoke about taking all his newspapers and making soles for his shoes, out of them, so that he could go to work. And they were badly treated by most of the guards. They felt like slaves. My father felt like a slave.1

10. The Power of Memory

1915-1917

A photo of internees returning to Six Mile Camp after a hard day's labour. While this lake is an idyllic getaway today, we cannot forget that it was once a prison for hundreds of men forced to build the road under armed guard and in deplorable conditions. It is an important cautionary tale for a country that prides itself as a champion of the values of tolerance, human rights, and justice for all.

* * *

The researchers Natalka Yurieva, Roman Zakaluzny, Amelia Fink compiled the exhaustive Roll Call, listing the 8,579 men, women, and children interned by Canada during the First World War. So we know the names of those at Mara Lake. Some of the dozens were POW #130 Mike Babich, POW #130 Turay Bishufovich, POW #160 Joe Diduck, POW #185 John Krenbovich, and POW #241 Cassia Portolowsky.1

Think about what was done to those men while you stand on this beach. These were men who came to Canada upon our government's express invitation, hoping to follow their dreams and build a better life. That they were so quickly and callously betrayed is a sobering lesson for our own day.

This country has committed gross injustices to minorities many times before, and it is only with an awareness of the past, and vigilance in the future, that we can prevent any more dark chapters of Canadian history from being written.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

1. Settling Mara Lake

1. Lubomyr Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian-Canadians 1914-1920 (Kashtan Press, 2001), 5.

2. The Road to Mara Lake

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 63.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 89.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 10.

4. Kassandra Luciuk, Reinserting Radicalism: Canada's First National Internment Operations, the Ukrainian Left, and the Politics of Redress, (online) 5.

5. Bohdan S Kordan, No Free Man, (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 6 .

3. Not So Divided Loyalties

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 30.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 30.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 57.

4. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 71

5. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 67.

4. Forced Labour

1. Kordan, 103.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 78.

3. Kordan, 114.

5. Building the Road

1. H.D. Gibson, "Orogenic superstructure and infrastructure and its role in the Tectonic Evolution of the Southern Canadian Cordillera", Canadian Tectonics Group, (Simon Fraser University, 2017), 5.

2. Kordan, 143.

3. Kordan, 144.

4. Kordan, 161.

5. Kordan, 145.

6. Kordan, 145.

6. The Guards

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 20.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 18.

3. Kordan, 145 - 146.

7. Facing the Elements

1. Kordan, 145.

8. Six Mile Camp

1. Kordan, 97.

2. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 50.

9. Vasyl Doskoch

1. Greg Laychuk Monashee Internment Camp, Youtube Video, (Vancouver, BC: The Community Health and Social Innovation Hub, University of Fraser Valley, 2021), online.

10. The Power of Memory

1. N. Yurieva & R. Zakaluzny, "Roll Call: Lest We Forget," Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund, online.

Bibliography

Gibson, H.D. "Orogenic superstructure and infrastructure and its role in the Tectonic Evolution of the Southern Canadian Cordillera." Canadian Tectonics Group. Simon Fraser University, 2017. https://www.canadiantectonicsgroup.ca/uploads/1/0/9/2/109291477/ctg2017_fieldtrip_guide.pdf.

Kordan, Bohdan S. No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the enemy alien experience. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016. E-book.

Laychuk, Greg. Monashee Internment Camp. Youtube Video. Vancouver, BC: The Community Health and Social Innovation Hub, University of Fraser Valley, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEXBrZG5kyg

Luciuk, Kassandra. Reinserting Radicalism: Canada's First National Internment Operations, the Ukrainian Left, and the Politics of Redress. University of Toronto. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/PDF/documents/Reinserting%20Radicalism%20by%20Kassandra%20Luciuk.pdf

Luciuk, Lubomyr. In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914-1929, Kingston, ON: Kashtan Press, 2001. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/ebff0f_30f6760f27d54baa8fb170503346967e.pdf

Tahirali, Jesse. "First World War Internment Camps a Dark Chapter in Canadian History." CTV News, Aug. 3, 2014. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/first-world-war-internment-camps-a-dark-chapter-in-canadian-history-1.1945156

Yurieva, N. & Zakaluzny, R. "Roll Call: Lest We Forget." Canada First World War Internment Recognition Fund. http://www.infoukes.com/history/images/internment/pdf/roll_call.pdf