Walking Tour

Unearthing Injustice

Archaeology at Morrissey

Alexa Dagan

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, the Canadian government quickly classified any immigrant from an enemy nation as an 'enemy alien, leading to the curtailment of their civil rights, and in many cases, their arrest and internment in camps.

As the war intensified, people around Fernie increasingly viewed those 'enemy aliens' working in the region's mines as competition for scarce jobs. After a labour dispute in June 1915, the government decided to intern these men at the Fernie ice rink.

The story of these men living and working around Fernie, and how they came to be interned, is covered in detail in the Fernie walking tour, Valley of Hope and Betrayal.

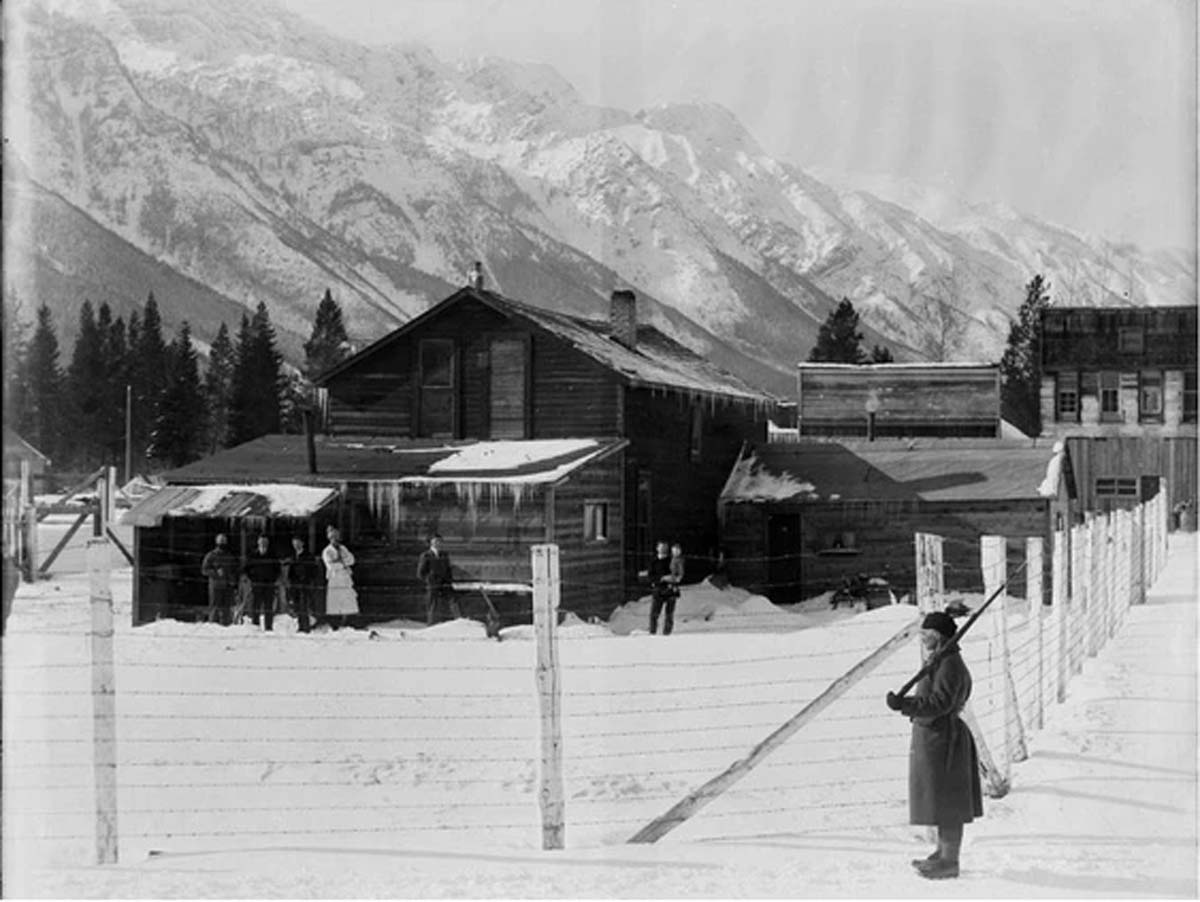

In the fall of 1915, these internees were transferred to an internment camp at Morrissey, just south of Fernie. There these men would endure great privations, abuses, and humiliations at the hands of the Canadian government for years. The camp was finally closed in October 1918, just weeks before the end of the war.

Much information about these internment operations has since been lost, making telling the story of the Morrissey Internment Camp especially challenging.2 Today, there are limited records that survive, and to fill in the gaps, we are turning to archaeology.

This article explores the recent excavations at the Morrissey Internment Camp, conducted by archaeologist Sarah Beaulieu and her team of undergraduate and graduate students from across Canada. Read along as we learn more about the field of archaeology and what buried objects can teach us about the realities of life in an internment camp.

Today the entire Morrissey Camp site is overgrown by thick forest and vegetation. It was located in this general area, just off the road, but we strongly discourage any readers from attempting to find the site's exact location in order to preserve its integrity for future archaeological excavation.

We would like to thank Sarah Beaulieu for providing her thesis and allowing use of her research. We would also like to express our gratitude to the entire archaeological team for their work in helping to bring this important chapter of Canadian history to light.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Rediscovering a Dark Chapter

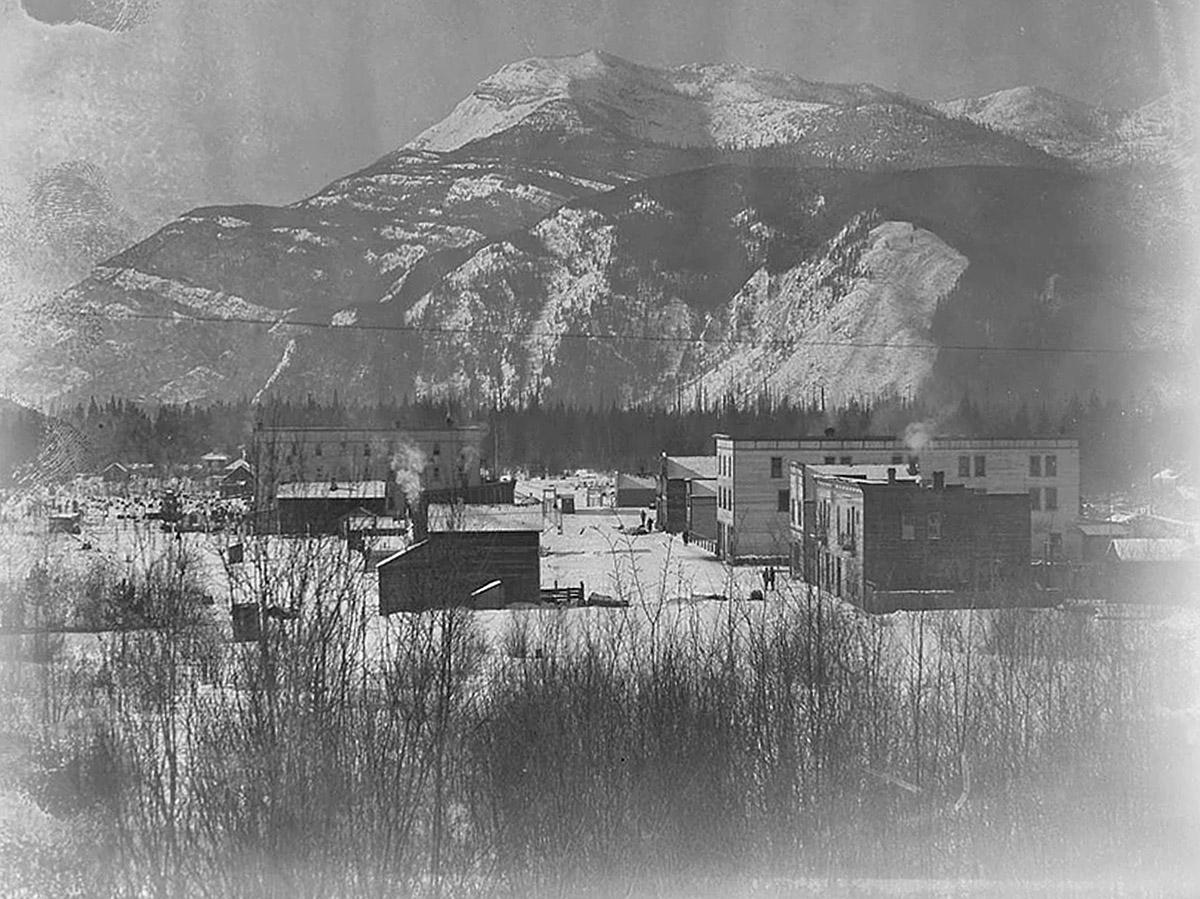

1916

History of Internment at Morrissey

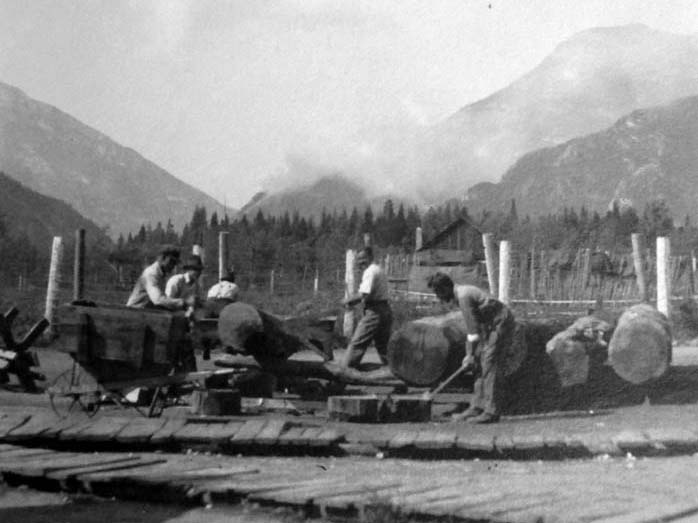

Internment in the Fernie area began with a strike. In June 1915, Fernie was facing high unemployment, and many regarded German and Austro-Hungarian immigrants with suspicion. Many of these immigrants were employed at the Coal Creek Mine, while others were unemployed. In June of 1915, Anglo-Canadian Coal Creek miners went on strike, refusing to work alongside "enemy aliens" when so many miners from Allied nations were out of work.

A disruption in coal production during wartime was a serious concern to officials, and BC's Attorney-General and acting premier, William Bowser, moved swiftly to quell the unrest. He announced that all German and Austo-Hungarian miners who were unmarried or whose families remained in Europe would be interned. This would open up jobs for--as he put it--more "deserving" men.3

290 men were temporarily imprisoned at Fernie's ice rink.

At first, the federal government considered Fernie's internment illegal, as the Coal Creek miners weren't a threat to national security. However, when miners at Hillcrest, Alberta, followed suit, officials feared this could set off a strike wave across Canadian mines. To avoid a potential halt to coal production, the federal government invoked the War Measures Act to take Fernie under the umbrella of national internment operations. 4

As the war dragged on, Canada faced a massive labour shortage as men were sent overseas. The federal government saw the internment camps as a source of underutilized and cheap labour. The internees at Fernie could be made to work on road construction for wages pegged to that of soldiers. This was significantly less than what they would have earned in the same job as free citizens.

Internees earned 55 cents per day of hard physical work but kept barely any of it. Half of their wage was held in trust by the government and was intended to be returned to the internee upon their release. Internees also had to pay room and board for their own forced internment. After all of these deductions, prisoners ended a day of work with only 12 cents.5 Imagine how it must have felt to be imprisoned under dreadful conditions and forced to perform back-breaking labour despite being innocent of any crime, all while still being expected to pay rent.

Thus, that fall, Fernie's internees were moved from the ice rink to Morrissey, a largely abandoned townsite (coal mining town) just south of the town, where they could be put to work.

The Morrissey Camp in particular was notorious for its mistreatment of internees. Samuel Gintzburger, the diplomatic official responsible for inspecting the camp, submitted a report to the Swiss government that stated the food internees were provided was worse than what was given to prisoners at criminal institutions, and that the heating in the Austro-Hungarian's quarters was insufficient for Fernie's severe winter. He also questioned the legality of forcing internees to perform physical labour.6

Gintzburger, as the Swiss Consul, had the power to report such concerns thanks to the Hague Convention. Canada signed this agreement in 1907, and it was intended to establish proper treatment of military prisoners in times of war. One stipulation was that internees could not be forced to perform labour that would benefit the war effort.

Canada had called its internees enemy aliens to justify their confinement but now had to fund these internment operations. To pay the bill, they extracted labour from the internees, making them pay for their own internment. The government then insisted that these internees were civilians, not combatants, and the rules therefore didn't technically apply.

Internees at Morrissey and other camps across Canada suffered through abuses and humiliations. First, as Gintzburger reported, many complained of the insufficiency and poor quality of the food. Many were given clothing inadequate for the harsh winter conditions. The labour was poorly paid and physically damaging; sickness and injury were constant companions. In addition, the avenues available to internees to change these conditions were slim. Refusal to work resulted in punishment, letters were censored, and the prisoners were worked to such extremes that they had little time or energy for anything else.

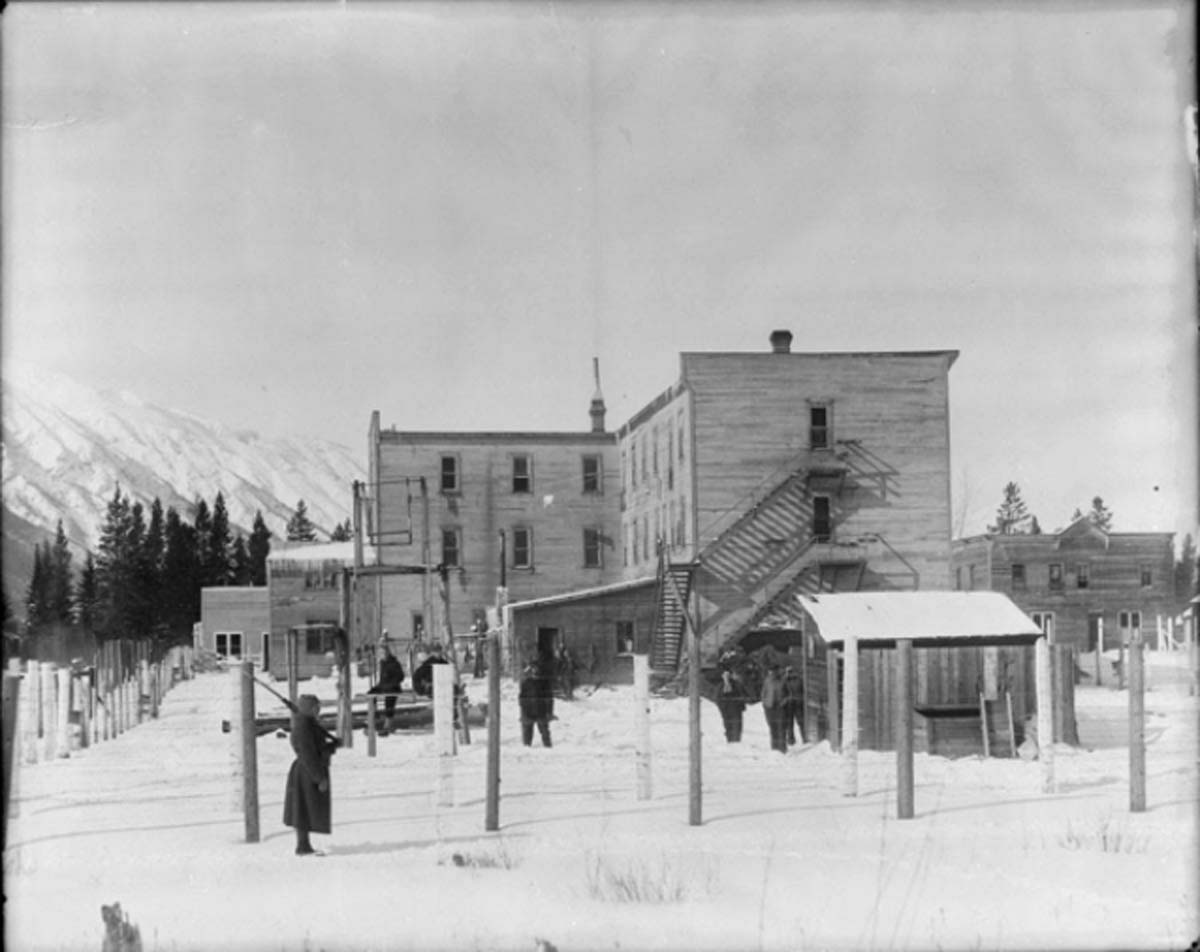

Not all internees were treated equally. The prisoners were sorted into the categories of first and second class based on their nationalities. Germans were considered first-class whereas those from Austro-Hungary were relegated to second-class status. First-class prisoners were treated better and were not compelled to perform labour, unlike those who were considered second-class.

* * *

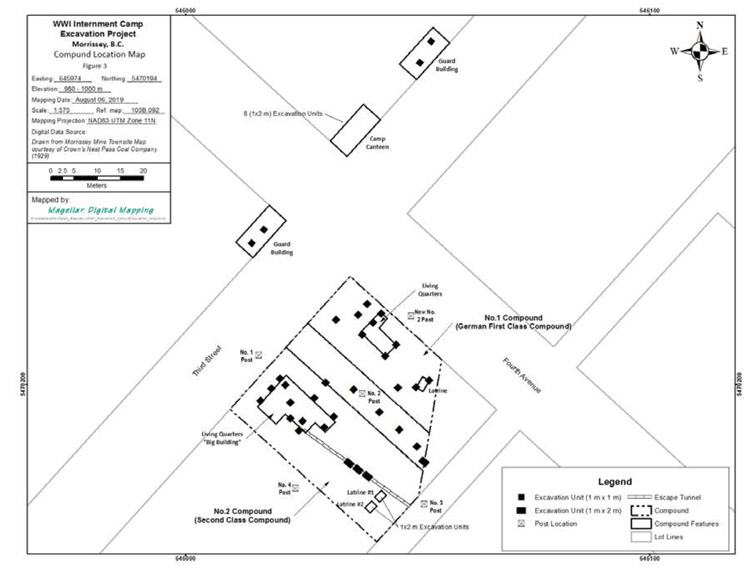

Several buildings made up the camp at Morrissey, but the entire complex was dismantled when the camp closed. When the archaeological team began to excavate, all that remained were the building footprints. First- and second-class internees lived in separate compounds. The second-class prisoners lived in the "Big Building", which was once a hotel in Morrissey. The third floor housed sleeping quarters for the prisoners, and the second floor contained the camp's rudimentary hospital and more sleeping quarters. The kitchen, dining room, reading room, and guards' room were all on the first floor. The first-class internees had indoor plumbing in their building, while second-class internees used outdoor privies that forced them to leave the heated buildings in winter.

Aside from the prisoner compounds, the camp also contained guard stations, a camp canteen, some privies, and an escape tunnel that was discovered shortly before a planned escape.

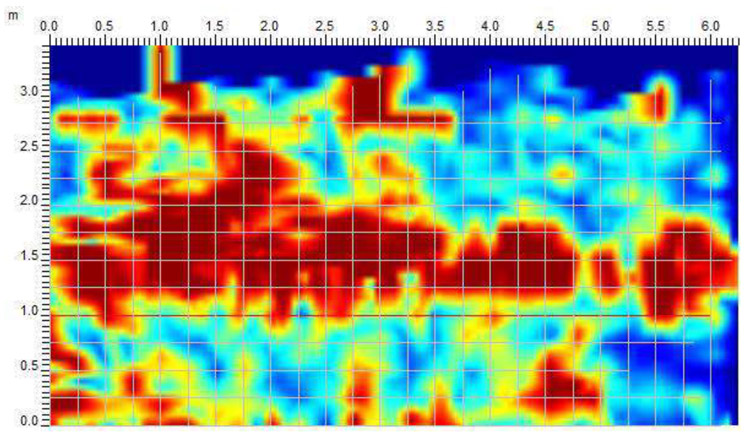

A nearby cemetery is also associated with the camp and contains the graves of those who died at Morrissey while it was in operation. When the cemetery was surveyed, only a few graves were visible on the surface. The use of Ground Penetrating Radar revealed 20 potential graves in total.7

An Archaeologist's Role

Archaeologists needed to consider several factors before excavating Morrissey. In studying the past, an archaeologist will sometimes work with the descendents of the community they are researching. For Morrissey, the events are still raw and researchers are only removed from internment by two or three generations. When planning a study such as this, an archaeologist has to consider how the descendents of internees and the local community might feel about a team of researchers digging up the lives of their ancestors. Do they consent to the dig? If so, what is the most respectful way to go about it? How can the community in question be included in and benefit from this study?

Archaeologists must also decide the extent of the excavations they plan to conduct. Archaeology is inherently destructive; the act of excavating and removing artifacts disturbs the context of a site—the location, position, and depth of artifacts and their relationships to other artifacts, graves, or structures. Each of these factors gives an archaeologist clues about the significance of the artifacts and the site itself. Therefore, when archaeologists are planning their approach, they often choose to do as little excavation as possible in order to preserve the integrity of the site.

New technology also makes it less common for archaeologists to perform unnecessary excavations. However, in cases when land is about to be developed or artifacts are at risk of being damaged or lost by natural erosion, excavation is necessary. In other cases, such as Morrissey, archaeologists excavate a site for public education or on behalf of a consenting descendent community who wishes to learn more about their ancestors. Conducting archaeology without the consent of the descendent community, as was frequently done in the past, is extremely unethical.

At Morrissey, excavation has not only raised awareness of a dark chapter in Canadian history but created an opportunity for closure for the descendents of those who were interned or stationed at Morrissey. Archaeologists consulted with the local community and ensured they had opportunities to be involved in the process. Before excavation began on the internment site, members of the descendent and local community were invited to attend a ceremony where Father Andrew Applegate, a Ukrainian Catholic priest, blessed the site.

On the final day of the excavation, a ceremony was held at the Morrissey Cemetery to honour the prisoners who died at the camp. Prior to the ceremony, community members, businesses, archaeologists, and the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund (CFWWIRF) all contributed physically and financially to rebuild the cemetery, install memorial plaques, and clear brush and debris from pathways. During the ceremony, two Ukrainian Catholic priests and one Ukrainian Orthodox blessed the site. Members of the CFWWIRF, local political representatives, museum directors, and community members all attended to mark the end of the dig.

Preparing to Excavate Morrissey

Sarah Beaulieu and her team began their survey of Morrissey by using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR). GPR detects objects and variations in soil composition by emitting pulses into the ground. When an electromagnetic impulse hits something, a signal bounces back, like an echo, and a receiver records the data. Software built into the GPR system then translates these signals into hyperbolic images that the archaeologist interprets in order to determine the location, shape and size of the objects (anomalies) hidden in the soil. Archaeologists can get a sense of what structures, objects, or graves might lie beneath the surface without breaking ground.

Using GPR, maps, historical sources, aerial photographs, and metal detectors, the archaeologists at Morrissey were able to accurately map the site's structures. Then, they conducted tests every five meters with shovels and augers to detect any subsurface anomalies. Testing this way allowed them to pinpoint which areas to excavate.

The team then excavated plots measuring one by two meters or one by one meter at the German first-class prisoner living quarters, the camp canteen where guards and internees could purchase goods, the "Big Building" in the second-class compound, the escape tunnel, and two of the camp's privies.

The Artifacts

The collection of artifacts recovered from Morrissey reflects the many interconnected facets of daily life, such as diet and health, self-care and leisure, resistance and expression, and faith and identity. For internees, sickness, abuse, discomfort, exhaustion, and an insufficient diet contributed to poor physical health, but mental health suffered as well. During and after internment, several internees in BC were sent to psychiatric facilities for the trauma they suffered in confinement. Some Morrissey prisoners were sent to BC's provincial psychiatric facility, Essondale Hospital (later named Riverview), beginning in 1917 and 1918.8

In response, the YMCA intervened at Morrissey and provided aid to boost prisoner morale. In addition to supplying reading material, they also set up a schoolhouse where Prisoners of War taught courses in arithmetic, accounting, carpentry, languages, art, and motor engineering. While this was a positive development, it was relatively late in the camp's operations. In the years prior, internees occupied themselves with camp labour, playing in or listening to the camp's PoW orchestra, gardening, and arts and crafts.

Leisure outside of labour helped internees' mental health by providing them with camaraderie, a sense of control over their circumstances, and an outlet for self-expression.9 Evidence of these activities can be seen in some of the artifacts at Morrissey. Paint vessels and inkwells were found in the tunnel that internees dug during an escape attempt.

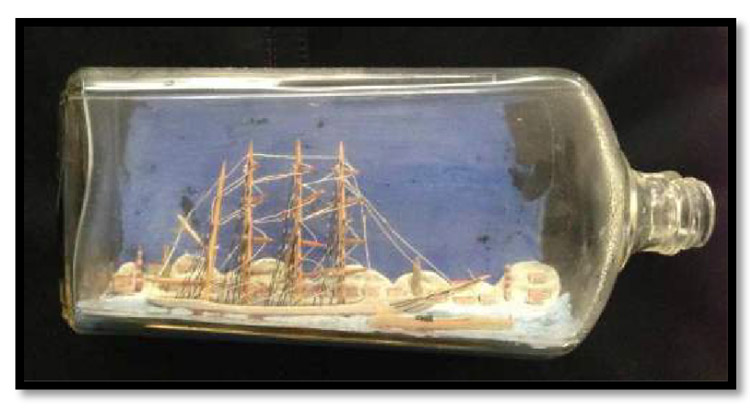

Several of the internees were skilled woodworkers, and archaeologists found 42 woodworking files in the second-class compound. These files, along with other craft supplies, could be purchased at the camp canteen. Archival photos also show us internee creations: ships in bottles or in lightbulbs, frames containing collected butterfly specimens, "swagger" or walking sticks, board games, grandfather clocks, paintings, and musical instruments. These items could be sold or traded for other goods to supplement an internee's meagre income.10

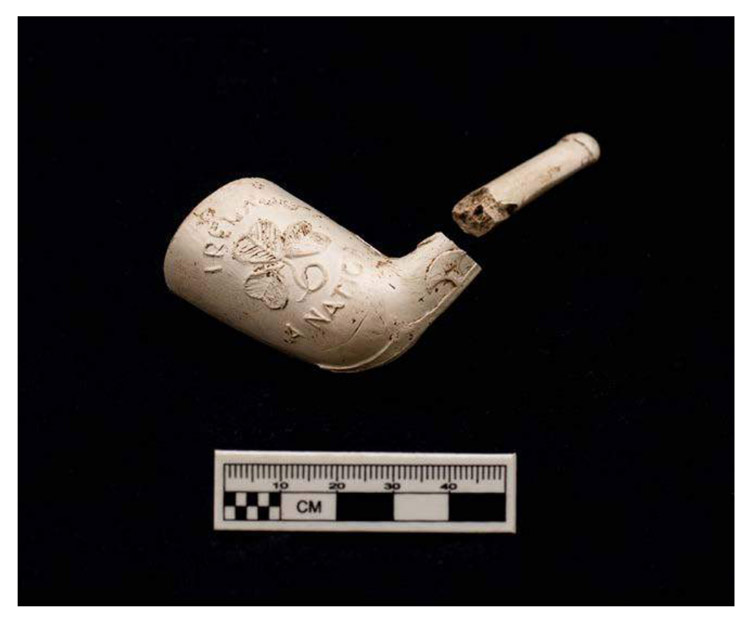

Tobacco and alcohol consumption also provided a distraction from the realities of internment. Archaeologists found numerous tobacco tins representing a wide variety of brands and types of tobacco. A plastic mouthpiece attachment for a pipe and an intact Irish clay pipe were both excavated from a second-class privy.

Interestingly, this pipe has strong ties to Irish nationalism. It reads "Ireland A Nation" on one side and "Who fears to speak of '98" on the other. A nationalist Irish pipe may seem like an odd find in a camp composed primarily of Ukranians, but it indicates an act of resistance against internment. Germany made alliances with nationalist groups in Ireland and India during the war to weaken Britain. Additionally, the Irish cause of liberation and freedom from British rule may have been relatable for some in the camp.11

In Ireland, clay pipes became a medium to express political thought, either through subtle symbolic imagery with the round tower, Irish wolfhound, or shamrock, or with more direct inscriptions such as those on this clay pipe. “Through the act of smoking it was possible to support the Irish nationalist movement without uttering a single word; it was only necessary to raise a pipe and puff” (Hartnett 2004: 140–41). These political pipes were symbolic of the smokers’ anti hegemonic principles and were subtle enough to be appreciated only by those in the know.

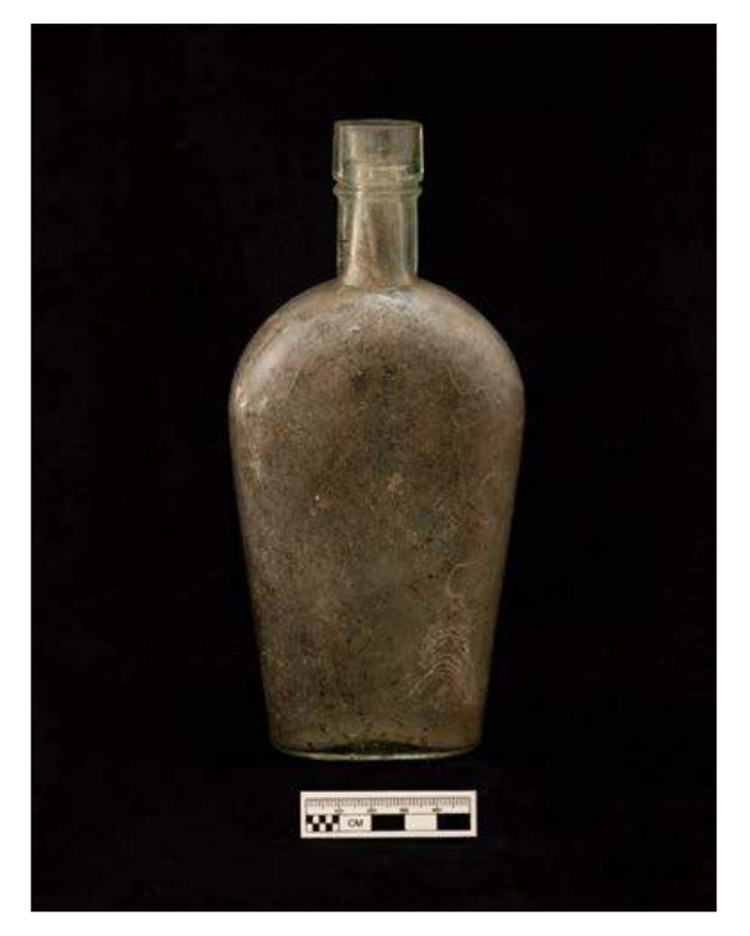

Beverage bottles thought to have contained alcohol were also excavated from both the first- and second-class compounds and the canteen. While internees weren't allowed to purchase alcohol from the canteen, the guards could and would sell or trade alcohol to the prisoners. Since the guards benefitted from this arrangement, it is likely that they looked the other way as long as internees didn't cause trouble while drinking.

22 kilograms of bottle glass was excavated in total. The majority came from Privy 1, while only three kilograms of glass was pulled from Privy 2. The disparity in these numbers relates to wartime prohibition laws. BC introduced wartime alcohol prohibition in 1917, and this was made national in 1918. Based on a variety of factors, archaeologists estimate that Privy 1 was used prior to 1917 and prohibition, while Privy 2 was used after. Prohibition shut down the sale of alcohol at the camp canteen entirely, meaning that any bottles that were disposed of in Privy 2 were camp contraband.12

Artifacts also reveal details about internee health. Archaeologists excavated pharmaceutical bottles at the canteen and at both compounds. Although the German prisoners made up only about 20% of the inmate population at Morrissey, their compound contained roughly the same amount of medicinal bottles as the Austro-Hungarian compound. Due to this, Beaulieu suggests that the so-called first-class prisoners may have received better medical treatment.13

Out of these medical bottles, only two can be identified. Archaeologists often rely on all of their senses to identify artifacts; a sniff of a bottle found in Privy 1 led the team to believe it contained eucalyptus. This ingredient was, and still is today, commonly used to treat chest and sinus ailments. The other bottle contained St. Jacob's Oil, which was intended to relieve muscular pain due to exertion or exhaustion. The active ingredients are herbal substances like camphor, oil of camphor, and oil of thyme, but the drug also contains more insidious chemicals such as chloroform, aconite, and turpentine.14

An iron tonic bottle was also found in Privy 1. People who took iron tonic believed that it had recuperative and strength-building effects and could treat the anemia suffered by tuberculosis patients.15

Each of these bottles reflects some of the common health concerns at camp. Both tuberculosis and influenza outbreaks occurred at Morrissey. Out of the four inmate deaths that were officially recorded, three were attributed to tuberculosis.

For some at the camp, faith may have provided some comfort among the dehumanizing and often abusive conditions. While priests were permitted to visit internment camps across Canada, there is no evidence that they visited Morrissey nor that the camp held any official church services or routine prayers. Additionally, there is little documented evidence that any organized religious activity took place at Morrissey. This makes the discovery of a handmade cross constructed from barbed wire all the more evocative.

The cross was discovered in Privy 1—how it got there is anyone's guess. The barbed wire invokes biblical imagery such as the crown of thorns placed on Jesus Christ's head at the crucifixion, drawing a powerful parallel between the suffering of the internees and the suffering of Christ.16 It also reveals the resourcefulness of the internees in using what was available. This artifact and the rest of the collection from the Morrisey excavation are now housed at the Canadian Museum of History.

Meat and Bone

Archaeology often involves sorting through the garbage of the past. What may be considered waste to many is a vast source of valuable information to archaeologists. A kitchen trash bin containing the remains of your weeknight dinner can say a lot about you, if someone knows how to look.

Official documents detail the supplies that were provided to the Morrissey Camp to feed the internees, but these reports miss vital details. On paper, it appears that Morrissey closely followed the rules laid out by the 1907 Hague Convention, which stipulated that Prisoners of War must be provided with basic human sustenance. Following these recommendations, the official rations for Canadian internment were set at 2,595 calories per day per adult man. This caloric requirement is slightly higher than what Canada's modern nutritional guide recommends, which is 2,500 calories a day in order for most men to maintain their weight.17

While the paper records seem to indicate that Morrissey was closely following these rations and that the prisoners were adequately fed, internees reported otherwise. Complains about the lack of food and its poor quality were frequent. One prisoner attempted to write a letter to the Swiss Consul stating that the internees' rations had been significantly reduced, but the complaint was censored.18

The official daily ration for the prisoners consisted of 2 lb of bread, ¾ lb of meat, 1 oz. of bacon, 1 lb of vegetables, 1.5 lb of potatoes, 4 oz. of jam, and 2 oz. each of coffee, sugar, and butter. Eggs were only provided once a month, rice or oats frequently took the place of meat, and fermented cabbage replaced fresh vegetables.19 While this supports the complaints that the food lacked variety, the official documents call into question the internees' claims that they were on starvation rations. There were some official cuts to the rations over the course of the war in accordance with wartime rationing, but even with these reductions the records meet the minimum for a basic sustenance diet. The archaeology suggests otherwise.

Beaulieu and her team excavated not only man-made artifacts, but also a variety of animal bones. Faunal analysis, or the study of the remains of non-human species, can reveal information about the diets of people in the past.

The majority of the faunal remains were found in the second-class compound privies and at the camp canteen. Camp expense reports detail the dates that certain cuts of meat were provided. By comparing these documents with the specimens that archaeologists found in the privies and the known manufacturing dates of other artifacts found in the privies, the archaeologists could establish the years during which each bathroom was used and verify other information in the written documents.

To analyze the faunal bones, archaeologists had to answer a few questions. What species do the bones belong to? How old were the animals? And is there any evidence of butchery marks or burning on the bones? Once the specimens' ages and species were identified, researchers could discover what cuts of meat the bones represented based on the marks left by the butchers who cut them.

The most common species in the assemblage was sheep, followed closely by cow. Pig, wild turkey, mule deer, bear, and chicken were also present in smaller amounts. Researchers further deduced that based on the cuts of meat that they could identify and the dates of the privies, the quality of the meat declined between 1916-1917 and 1917-1918. While all of the cow specimens they found were mature animals, the sheep bones came from animals of a variety of ages; some showed signs of advanced age, which would indicate poor quality meat. The pig bones that were found were also from the cheapest and toughest cuts of meat.20

Sarah Bealieu writes:

The AGWMA [Auditor General's War Appropriation] reports document a 27,650-lb reduction in meat supplied to the camp between 1916–17 and 1917–18. Specifically, beef was reduced from 109,904 lb in 1916–17 (Privy 1) to 82,253 lb in 1917–18 (Privy 2). The same report indicated that mutton was reduced from 1,559 lb to 976 lb during the same period. This is significant since 80 additional PoWs were imprisoned in Morrissey in 1917–18. Interestingly, the excavations reveal an observable increase in Bovinae [Cow] (52%) and Caprinae/Ovis aries [goat/sheep] bones (64%).21

These recorded reductions occurred due to wartime rationing, but this statement raises an important question. If the internees were receiving less meat, why did the number of bones increase?

The answer is the declining quality of the meat that was provided to Morrissey. Lower quality cuts of meat typically contain more bone. On paper, these cuts were the same weight as the better quality cuts, but more of that weight consisted of bone and not meat. This meant that as internment continued, the internees were getting far less edible material out of the cuts of meat that they were sent. This allowed officials to disguise unofficial reductions to the internees' diets on top of the rationing cuts they recorded. It also helped them cut costs. Despite the reduction in both the quality and quantity of meat, internees usually did not pay any less for their room and board.22

There are several other clues that support the conclusion that the internees' diets were insufficient. First, several of the bones were cracked open for their marrow. Marrow would have added some nutritional value to the food of an underfed prisoner population. Second, bones found at the camp canteen suggest that the internees were spending their hard-earned, meagre wages buying additional food. Finally, some of the bones belonged to wild game species, which were never officially supplied to the camp. The internees were not hunters and had any weapons taken from them before arriving at camp. Wild meat was probably sourced from local hunters either through purchase or trade.23 If the meals were sufficient, why would internees spend what little money they had on basic subsistence foods like meat?

However, survival staples were not the only option at camp. The excavation also revealed containers for some comfort foods that could be purchased at the camp canteen. These include containers for syrup, cocoa, chocolate, coffee, sardines, and corned beef. Significantly, these items were found in limited amounts, and they were only present in the escape tunnel. Not only are these foods high in calories and easy to preserve but they are also highly portable. This led Beaulieu to propose that these high-value items were stockpiled as supplies for an escape attempt.24

In this case, the historical record is misleading. The documents suggest that while some foods were reduced due to wartime rationing, the meals were still adequate for the prisoner's needs. However, the archaeological record tells us that meals contained more bone than meat and that internees relied on outside sources for dietary supplements and stockpiled precious foods for a risky attempt to escape their dire conditions.

Escape Attempts

Despite exhaustion, malnourishment, and illness, internees at Morrissey were not passive victims of internment. Rather, evidence suggests that they resisted in whatever ways they could. While refusal to work, strikes, and the breaking of camp rules all provided avenues for the internees to express their unhappiness, these methods rarely produced positive change and invited severe punishment. Punishments could include confinement in a camp cell, cuts to their rations, or a transfer to a harsher camp. The most high risk, high reward way to resist captivity was to escape it.

Escape from a PoW camp took one of two routes: either over the barbed wire or under it. Going "over" the barbed wire was the simpler of the two and was usually attempted during work details outside of camp. An entire work party from Morrissey labouring on a road project near Cranbrook successfully escaped. Another year, three internees escaped into the forest while their work party was cutting wood. A fourth internee shouted "porcupine!" to distract the guards while the other three successfully disappeared into the forest. In April of 1918, another man attempted to make a break for it but was caught after 45 minutes.25

If escaping during a work detail outside of the camp wasn't possible, the only option was to escape under the wire. Morrissey is one of only four camps in western Canada known to have had escape tunnels. The Vernon, Lethbridge, and Yoho Field camps also had escape tunnels, but they were only used successfully at Vernon and Lethbridge. Significantly, at these two camps, it was the German first-class prisoners who escaped.

Beaulieu writes:

Escape 'under the wire' required a vast amount of time and energy, not only to dig the tunnel but to prepare for travel upon reaching the other side of the barbed wire: stockpiling food supplies, increasing physical fitness and endurance, acquiring civilian or military clothing, reading maps and memorizing escape routes, procuring essential escape tools such as compasses, wire cutters, and language translation books—and keeping everything concealed from the guards.26

While the German prisoners had ample leisure time to adequately prepare for an escape, the second-class prisoners were forced to perform exhausting labour. They had little time or energy to conduct escape attempts, and the small chances of success and severe punishment if caught made the endeavour too high a risk for many.

Despite this, conditions at Morrissey were dire enough for the second-class prisoners to take the chance. The first step to digging an escape tunnel was to secure the aid of any internees with mining experience. These men were accustomed to digging underground and had the expertise needed to build a secure and structurally sound tunnel. The Morrissey tunnel shows evidence that internees pulled slats from their beds to reinforce the walls and ceiling. A shovel recovered from the tunnel is similar to those used in coal mines but appears to have been handmade based on that example rather than manufactured.27

The story of the tunnel's failure can also be deduced from the archaeological record. The tunnel was discovered shortly before the planned escape, opened from above, and filled with camp garbage that was then burned to prevent future use. Paint cans, jars, inkwells, and crafting items coated in a layer of ash and melted glass were all found, suggesting that items were pulled from the camp's refuse and tossed into the tunnel to block it before the guards burned the whole thing. Other artifacts such as food containers and personal items were likely packed in preparation for the escape.28

Escape attempts were common in internment camps across Canada, but in most cases, they were unsuccessful. For those who were recaptured, the punishments were severe. In addition to the usual punishments used in camp, in some cases, corporal or capital punishments were employed. Court records explain how internees were punished if they were too sick to get out of bed: "Prisoners found on their beds at daytime, were punished with as much as 6 days in the cells at half rations and in spite of their feeling unwell immediately arrested and forced to do humiliating work for the guards in the guardroom. Anybody refusing to do this was treated with bodily punishment."29

Aftermath

When the war ended, the camps were slowly shut down and the internees released. Yet despite the abuse and despair caused by the camps, the federal government again enacted the same strategy during World War II and interned "enemy aliens". Many internees were German Prisoners of War, but Japanese and Japanese-Canadian civilians, as well as some Italians, Mennonite conscientious objectors, and Jewish refugees from Europe were interned as well. Japanese civilians represented the largest proportion of internees in Canada during WWII, and the injustices of these camps are well-documented through records and the words of survivors.

Notably, the First World War camps interned mostly men. Only 81 women are on record as being interned, and only two camps in Canada housed women and children: Spirit Lake in Quebec and Vernon in British Columbia. During the Second World War, however, entire Japanese families were interned together. Sixty per cent of these internees were Canadian-born and 77 per cent were Canadian citizens.30

Decades after Canada's first internment operations ended, Ukrainian survivors began to pursue redress for their ordeal. The campaign was led by the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA) and internment survivor Mary Manko Haskett, who was interned at Spirit Lake as a child. Her younger sister did not survive the ordeal. Haskett and the UCCLA didn't ask for an official apology from the Canadian government, nor did they seek financial compensation for the victims. Instead, their campaign focused on raising public awareness about internment and remembering both those who died in the camps and the trauma suffered by survivors.

In 2008, as part of the initiative started by Haskett and the UCCLA, a $10 million community settlement fund now known as the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund (CFWWIRF) was established to continue supporting commemorative projects and initiatives to educate the public about internment. The settlement was signed at a significant location: the Stanley Barracks in Toronto, which served as a “receiving station” for internees during the war.31 Sarah Beaulieu's excavation of Morrissey and the publication of the article you just read are both beneficiaries of this grant and part of the effort to honour and remember the people who lived and died in Canada's internment camps.

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

- 1. Desmond Morton, "First World War (WWI)," The Canadian Encyclopedia, Aug. 5, 2013. Updated August 24, 2021. Webpage.

- 2. Andrew McIntosh, "Ukrainian Internment in Canada," The Canadian Encyclopedia, June 5, 2018. Webpage.

1. Rediscovering a Dark Chapter

3. Sarah Beaulieu, "Archaeology of Internment at the Morrissey WWI Camp," Phd thesis, (Simon Fraser University, 2019), 28.

4. Beaulieu, 29.

5. Beaulieu, 48.

6. Beaulieu, 29.

7. Beaulieu, 3.

8. Beaulieu, 30.

9. Beaulieu, 36.

10. Beaulieu, 39.

11. Beaulieu, 49.

12. Beaulieu, 53.

13. Beaulieu, 51.

14. Beaulieu, 51.

15. Beaulieu, 52.

16. Beaulieu, 46.

17. Beaulieu, 57.

18. Beaulieu, 57.

19. Beaulieu, 58.

20. Beaulieu, 81.

21. Beaulieu, 68.

22. Beaulieu, 86.

23. Beaulieu, 81.

24. Beaulieu, 86.

25. Beaulieu, 110.

26. Beaulieu, 100.

27. Beaulieu, 115.

28. Beaulieu, 116.

29. Beaulieu, 105.

30. Patricia E. Roy, "Internment in Canada," The Canadian Encyclopedia, June 11, 2020. Webpage.

31. Patricia E. Roy, "Internment in Canada."

Bibliography

Beaulieu, Sarah. "Archaeology of Internment at the Morrissey WWI Camp." PhD thesis. Simon Fraser University, 2019. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/PDF/documents/Sarah%20Beaulieu_Thesis_official%20Aug%2012-compressed.pdf

McIntosh, Andrew. "Ukrainian Internment in Canada." The Canadian Encyclopedia. June 5, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/ukrainian-internment-in-canada

Morton, Desmond. "First World War (WWI)." The Canadian Encyclopedia. August 5, 2013. Updated August 24, 2021. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/first-world-war-wwi?gclid=CjwKCAjwkvWKBhB4EiwA-GHjFraAREOIPMvcq5_EzfUyvi_zxxfvTYVvlLZ4Iq3wayBJibhhNLsMxhoCQTsQAvD_BwE

Roy, Patricia E. "Internment in Canada." Canadian Encyclopedia. June 11, 2020. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment