Walking Tour

If These Walls Could Talk

Aurora's History told through Architecture

Andrew Farris, Shawna White, Michelle Johnson

In this tour we will discover the history of this town, as told through the buildings where generations of Aurorans lived out their lives. Few buildings survive from the town's humble beginnings as a quiet farming district some two centuries ago. Beginning in the 1850s however, when more people settled here, they brought with them an optimistic outlook on the future, and built homes and businesses designed to stand the test of time. Aurora is, after all, named for the Roman goddess of the dawn--and Aurora's dawn was thought to be especially bright.

The community grew into a village, and then a town, and Aurorans erected buildings to reflect that new status. Many of the buildings we will see on this tour are historic landmarks that have played key roles in the development of the community, such as the Public School, the Armoury, and the Train Station.

Some have not survived to the present. It took a long time for people to begin to awaken the value of preserving heritage buildings, and important buildings like the Inglehurst mansion, the Town Hall, and the Queen's Hotel, were demolished before most people could realize what had been lost.

In the 21st Century the community has made great strides in preserving and rehabilitating the buildings that tell the story of its early years, and with continued vigilance they will hopefully still be standing for generations to come.

This project is a partnership with the Aurora Museum & Archives and the Town of Aurora.

1. Aurora's Early Years

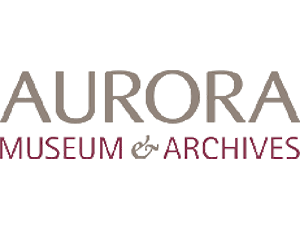

Aurora Museum & Archives 71.14.3-c-t

c. 1900s

This postcard view of Church Street shows the Aurora Public School at left, and the Trinity Anglican Church at the end of the street. The original Trinity Anglican Church building was constructed on this spot in 1846, making it an early pillar of the community.

In those days Aurora was a tiny farming community sitting astride Yonge Street and known as Machell's Corners after Richard Machell, the first man to build a general store at Wellington and Yonge. With the arrival of the railway and industry, the community grew steadily over the rest of the century, and in 1863 incorporated as the Village of Aurora. As a result of continued growth it was upgraded to a town in 1888.

The church building you see here today replaced the original in 1884. It is a fine example of the Gothic Revival architecture so popular at the time in the Victorian era.

* * *

The Governor hoped to populate this land with farmers loyal to the British Crown. With that goal in mind his surveyors divided the land on either side of Yonge Street into farm plots to be granted to those willing to farm and defend it. Two of the first to here were American Loyalists, William Graham and William Tyler, who had fought for Britain in the war and fled to Upper Canada to start new lives.1

The land on the east side of Yonge was simply called Whitchurch Township, and the west side, King Township. A few more farmers arrived, and for decades a small agrarian community continued life here, largely untroubled by the outside world. In the 1830s Richard Machell arrived and established his general store at Wellington and Yonge, and it became the central meeting place for farmers in the area.

The pace of change in these decades was slow. A map from 1851 gives us a sense of the quiet nature of the place. Over half the area was forested. There was a grist mill for grinding grain into flour by the creek on Tyler Street, and a small Methodist log church at Tyler and Yonge. But there do not appear to have been any other buildings on Yonge Street where the town's commercial strip is today.2 This was about to change.

2. The Public School

Aurora Museum & Archives 76.12.94

1904

This fascinating building was the Aurora Public School. It was completed in 1886 to replace an earlier one-room schoolhouse, and would serve as the growing community's main school for years to come. The future prime minister, Lester B. Pearson, began classes here in 1901 and apparently gained the nickname "smarty pants Pearson" for his mastery of Roman numerals.1 The building is no longer a school and escaped the wrecker's ball in 1981 by becoming an activities centre and home to the Aurora Museum.

* * *

Nevertheless, the building of this school showed how prosperous and optimistic a community Aurora was becoming. It was constructed in the exotic British India style that combined aspects of classical Indian architecture with British styles like Gothic Revival, and became popular throughout the British Empire in the late Victorian Era. The style is marked out by the stylized belfry tower over the front entrance, the patterned brickwork, and the bulbous globes on the roof line. The design was carried out by Thomas Kennedy, a remarkably versatile architect from Barrie. He designed over 100 prominent buildings in Ontario around this time in virtually all of the many style that were fashionable at the time.3

As the city continued to grow, the community's needs outgrew the old public school, and new ones were built. In the 1970s some local politicians claimed that the building was 'an eyesore,' and argued for its demolition.4 One of the few buildings in Ontario in the British India style, it is fortunate that the Aurora Historical Society, looking for a new home at the time, fought successfully to have the school turned over to them for use as a museum and activities centre.

Many other valuable historic buildings throughout Aurora have not been so lucky.

3. The Mechanics Hall

Aurora Museum & Archives 987.6.2

1916

This fascinating photo shows a column of infantry marching in the mud past the Mechanics Hall in 1916. They are members of the 12th York Rangers. Muddy unpaved streets were the rule rather than the exception until the 1920s. At that point more people began to buy cars, and the owners of those cars expected roads to be paved to accommodate them.

* * *

During the 19th Century, the sciences and engineering were not nearly as specialized as they are today, so any bright and curious mind could read and quickly grasp the latest academic papers--and perhaps use that knowledge to make their own innovations. After all, automobiles and airplanes were both invented around this time by curious bicycle repairmen. At a time when most libraries entailed expensive subscription fees, the Mechanics Institute allowed Aurora's poorer factory tradesmen and farmers to access books.

The Hall was also used for lectures and concerts such as the Temple of Fame. First performed at the Hall in 1918 to raise money for the Aurora Overseas Auxiliary, the pageant featured great female figures from history making their cases as to why they should be awarded the crown of fame. To celebrate its 100th anniversary, the Temple of Fame was updated and re-staged by the Aurora Museum & Archives over Mother’s Day weekend, 2018.

As for the Institute, in 1895 it became a freely-circulating public library. The library moved to the Town Hall on Yonge Street in 1920, and then moved several more times over the decades until reaching its current location at Yonge and Church in 2001. Today the building the home of the Romanian Orthodox Church.

4. The Town Park

Aurora Museum & Archives 2005.2.20

1945

A crowd of people have gathered in Aurora's Town Park to listen to speeches and celebrate VE Day - the surrender of Germany and the end of the Second World War in Europe. Town Park was originally the community's cricket ground before it was sold to the village in 1867. Ever since the park's founding it has hosted all manner of fundraisers, concerts, dances, political speeches, craft and horse shows. The Aurora Agricultural Society held Fall Fairs here that drew farmers from across York County to sell their goods and participate in competitions. The Aurora Horse Show was also held in Town Park from 1923 until it moved to Machell Park in 1971.

* * *

Writing in the 1920s, the Canadian Historical Review, said "There have been few political speeches in Canada which have been more justly famous, and which have exerted a wider influence on Canadian popular opinion, than Edward Blake's 'Aurora Speech'... In its bold and daring originality it gave a real stimulus to Canadian political thought. A speech which, nearly half a century ago, advocated such advanced ideas as the necessity for the growth of a national feeling in Canada, the reorganization of the Empire on a federal basis, the reform of the Senate, compulsory voting, and proportional representation, can only be described as a landmark in Canadian politics."2

5. The Queen's York Rangers

c. 1970s

Boys enrolled in the Queen's York Rangers Cadet Program parade in front of the Armoury in Town Park. The Armoury was built in 1874 to serve as headquarters of the Aurora contingent of the 12th York Battalion of Infantry (later the Queen's York Rangers). The Rangers continued drilling in the hall until as recently as 2012. In recognition of the long continued use of this unassuming building, it earned protected heritage status in 1991.

* * *

During the Second World War the Rangers were mobilized to serve in a home defence role, though many Aurora men were sent off to fight with other frontline units. All told, some 24 men from Aurora were killed during the First World War. In World War II the grim tally was 55.1

6. A 'Genteel Family' Home

Aurora Museum & Archives 86.36.9

1900s

This house, owned at the time by the Gower Family, was originally built in 1856. You can see members of the Irwin and Gower families standing out front. The simple, symmetrical Georgian style of home you see here was popular in Aurora, and many homes of this style have survived to the present.

* * *

" A comfortable two story dwelling house, newly erected, with every suitable convenience for the residence of a genteel family… situated opposite the railway station… There is also a well of excellent water. The location is healthy and desirable, being within one hour's ride of Toronto by railway."1

Homes like this were the standard for the working classes in the mid-1800s. While they lacked the modern conveniences of electricity and running water--which wouldn't arrive until the 20th Century in many cases--they were well-built and relatively spacious.

7. The Railway

Aurora Museum & Archives 992.16

c. 1900

This has been the site of Aurora's main train station since the first train arrived on May 16, 1853. You can see here some women and children on the platform, including Della Webster (second from right). Behidn them is a cart stacked high with suitcases in front of the old station, which has survived to the present with some minor alterations.

* * *

Railways were a fairly primitive new technology in the 1850s, and it was the pioneering work done on railways like this that laid the groundwork for the vast transcontinental railways that made Canada possible a short time later. It is no coincidence then that the historic railway station has survived to the present.

In an age before cars and highways, the railway brought most visitors to the city, and the station was the first place they saw. In 1886 one visitor to the town described their experience of arriving at Aurora's station to the magazine Rural Canadian:

"On stepping from the [railway] cars the clean and business[like] air of the place is very striking, no loitering, all on business intent. The sidewalks are excellent, and may be placed without fear of a plank springing up and barking your shins, or being tripped up, or stubbing your toes, and I hear ken, ye city fathers of more pretentious places, a man was kept scraping the mud off the roads and keeping them clean!"2

Accounts like this are a reminder of just how much we take for granted in the 21st Century. Who today would think it especially noteworthy that one can walk on the sidewalk without hurting yourself?

8. The Railroad Hotel

Aurora Museum & Archives 999.25.44

1971

This was the Railroad Hotel, built on land adjacent to the train station by the farmer John Kirsopp. In the 1850s he built this hotel to service visitors arriving by railway. (Railway is the Canadian term and railroad the American). In a fairly short time the hotel gained a reputation as a place to engage in the illicit "whiskey business". In 1888 an editor of the Aurora Banner deemed the hotel "without doubt the worst place inside the corporation."1 Nevertheless the building has proven long-lived and survives today in excellent condition.

* * *

"Aurora had and has many fine qualities, but a wealth of tourist attractions has never been among them. The hotels were not occupied by people who came to see the sights, or even by train passengers who wanted to break a journey with a good night’s sleep in a hotel: if you were outbound, you would not yet need to stop for the night, and if you were on your way to Toronto, why not just carry on to the big city and all it had to offer? "If you were visiting family or friends in town, you would stay with them: that is what spare rooms were for. "Much of the overnight trade for small town hotels came from travelling salesmen. "Commercial travellers formed a world unto themselves… They formed friendships as they repeatedly encountered their fellow 'drummers,' some of them rivals for the same business. On a wider scale, they came together in mutual benefit associations which also negotiated good rates with the railways and hotels. They even established charitable organizations to assist those in need beyond their own circles… "For the commercial traveller the hotel was not only a place to lay his head and eat his breakfast: it was a place of business. Here he planned his local campaign, organized his samples, and then, if all went well, wrote up his orders after a day of sales. He might even nip across to the station telegraph office to send those orders back to the home office.. If the traveller stayed at a station hotel he could be on the railway platform two minutes after checking out, ready to move on to the next town on his route. "Then there were the users of the hotel bars, mainly locals. "The tinkle of ice in glasses, some background music, the buzz of conversation and an occasional outbreak of laughter: this was not the ambience of the typical small hotel bar, in Aurora or anywhere else in nineteenth century Ontario. General rowdiness, drunkenness, and fights, all fuelled by inexpensive liquor, were more likely to be found at the Railroad Hotel, as we have seen, and at some other Aurora hotels. The local newspaper had many a report of the collusion of landlords in all this, selling liquor illegally. "But for going on 130 years now, the greater part of its life, the Railroad Hotel building has been quiet and well behaved, very far from its days of being the worst place within the boundaries of the municipal corporation of Aurora."2

9. Kindness of Strangers

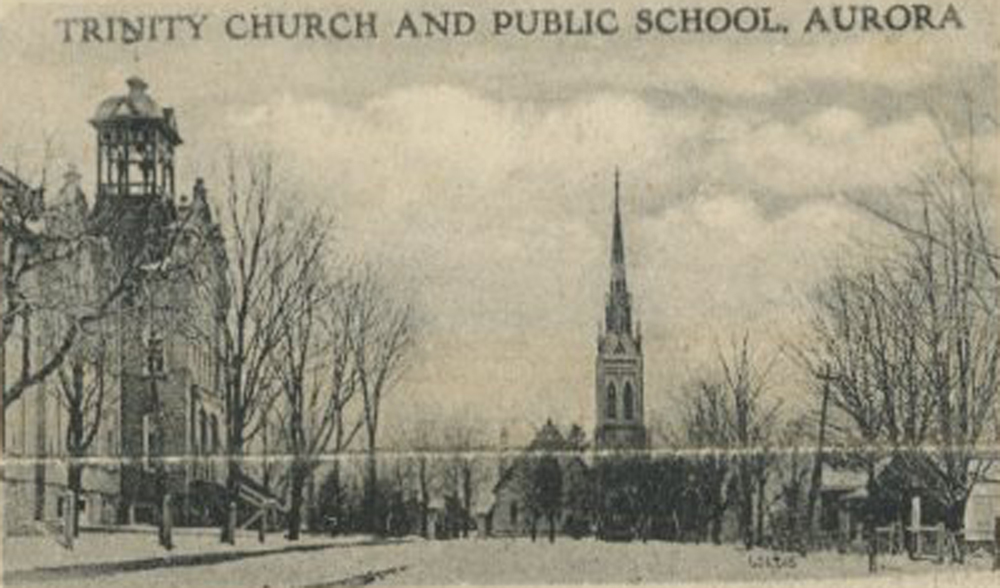

Aurora Museum & Archives 81.57.4

1931

This tower of snow resulted from a huge snowstorm on March 8, 1931. Mr and Mrs. Spalding are seen here posing with the structure on their quiet residential street. Aurora's quiet tree-lined streets, with their assortment of old, colourful homes, can't help but leave the visitor with the most positive impression.

The same was true over a century ago. The Brown family, visiting from Plainfield, New Jersey, visited Aurora in 1894 and wrote home to the Plainfield Courier to describe the experience.

* * *

"One of the unusual things here is the absence of drunkenness. We have not seen an intoxicated person or heard an improper word in the two weeks of our stay.

"We are welcomed by a look of friendliness in the stores and on the streets.

"The butchers on their delivery rounds in the morning call their customers out by a bugle. We first thought them a club of wheelmen [cyclists] coming.

"The town constable is a busy man. He rings the City Hall bell at six o'clock in the morning, at noon and at six o'clock at night, attends to the waterworks business and on market days, Thursday, is at the City Hall to set the prices of the day on farmers' products brought there for sale.

"We have visited the foundry, the brick and the tile kilns and were pleasantly shown about. We have seen no poor degraded persons, but all seem contented and happy. There is no element of the Plainfield hurry and worry."1

10. Inglehurst

c. 1920s

The grand home that once stood on this spot belonged to Joseph Fleury, Aurora's leading businessman and founder of the company that manufactured ploughs sold across North America.

The home he built here, named Inglehurst, was typical of those built by the captains of industry in the Victorian Era: enormous, lavish, and carefully designed to reflect one of the many eclectic architectural styles of the time. In this case the design was Gothic Revival, a style that looked back to to the late Medieval period for inspiration. Aspects of that style noticeable on Inglehurst are the tall arched windows, the tall sloping roofs, and the 'bargeboard'--the ornamental trim along the roofline that casts striking shadows in sunlight.

Inglehurst became one of Aurora's social centres and innumerable social events were held here for over a century.

The grand old mansion was purchased by the neighbouring Our Lady of Grace Church and demolished in 1980 to make way for the parking lot you see in front of you.

* * *

Inglehurst was more than a family home. When Canada’s Prime Minister, Alexander Mackenzie, visited in 1877, this was only the beginning of a fascinating history; Inglehurst became a destination for distinguished guests and community events--a source of local pride. Unfortunately, Joseph lived only four years in Inglehurst. His second wife, Sarah and their very young family continued living there after his death. In 1887, Joseph’s son Herbert, his wife Leila, and their young daughter Marguerite made Inglehurst their home.

Under Herbert, the Fleury home evolved into a centre of social life that reflected his magnanimity and community-minded nature. For example, Herbert opened the grounds for public high teas during World War I to raise funds for the Girls’ Red Cross Auxiliary. These events attracted motorists going through town, raising additional funds for Aurora’s war effort. Pictures of these teas can be found elsewhere in this app.

For many years, Herbert was also a director of the Aurora Horticultural Society. His gardeners carefully tended the grounds at Inglehurst and reports of Herbert’s produce made their way into the local newspaper. In 1919, Herbert’s table bouquet, collection of perennials, lettuce, hickory and endive all won first prize at the summer flower show held by the Horticulture Society – in 1927, his delphiniums.

Herbert Fleury died at Inglehurst in 1940. Upon her return from Paris in 1946, Marguerite sold the house and, in 1980, it was demolished.

Its tall, striking front doors with frosted glass panels, and a marble mantlepiece, still reside in Aurora. They await new life as a memorial to their grand past, on display or in a building to come.

11. Horton Place

c. 1880

This home is known as Horton Place. It is one of three fine homes that dominated the northern entry to Aurora on Yonge Street, the others being Inglehurst and Hillary House which are located just up the street. It was built in 1875 by Dr. Robinson, Aurora's dental surgeon. The house was an excellent example of the Italianate style which was popularized in Ontario by the Canada Farmer journal in 1865.

* * *

The third of the three prominent homes is Hillary House, located just north of Horton Place. Built for the town's doctor, the home was also threatened with the wrecking ball. The Hillary family, Aurora Historical Society, Ontario Heritage Foundation, and Parks Canada all banded together to save the home, and succeeded in turning it into a museum and home to the Aurora Historical Society.

12. Queen's Hotel

c. 1930s

Looking back east up Wellington, we see that even during the 1920s the streets were yet to be paved. On the left you can see the front of the Queen's Hotel. The Hotel was originally built in 1860 as Machell House, named after the man who first chose to build a store at this intersection. It was Aurora's largest and most elegant hotel.

* * *

Public awareness of the value of heritage preservation rose markedly in the 1960s and 1970s, but it would not come soon enough to save this important building. It was demolished in 1971 to make way for the TD Bank that remains there today.

13. The Fleury Works

Aurora Museum & Archives 987.4.4

Across the street from you were once located the factories of J. Fleury's Sons. They manufactured ploughs and agricultural implements that became so well known across North America that a Fleury plough was incorporated into the official town crest. The factories here had an enormous impact upon the development of the community, and would continue churning out ploughs until the 1960s.

The industrial buildings in this complex have survived to the present by taking on new tenants including present day owners Bacon Basketware Limited.

Tannery Creek runs to the west of Yonge Street was an excellent source of hydropower for Aurora's early industries, and it was here that a variety of mills and factories were situated. They included a grist mill and a tannery.

* * *

Like other successful pioneer owners of foundries in Ontario, Joseph had exceptional personal qualities: he combined inventiveness with good business sense, dogged determination and resilience. In 1862, an agent of R.G. Dun & Company of New York, paid a visit to Aurora and assessed the credit worthiness of five of its businessmen. In his judgment, Joseph was, “Honest and industrious (and) works hard at the trade. Has small means but intends doing business in a (professional) small way and thinks will pay his debts.”1

The following year, after noting that Joseph owned the foundry and a house worth $1,200, as well as 100 acres in Simcoe County, the agent sized him up as “Sharp and active, attends well to business, prospects good, means small but gaining.”2

As a testament to his extraordinary energy level, throughout his professional life Joseph would face the demands of running a successful business, raising a growing family, managing a political career and playing the role of an influential community leader in Aurora, and wider afield, in York County.

In 1937, J. Fleury's Sons merged with the Bissell Company. The head office and primary manufacturing plant was based in Elora, Ontario, and the Aurora location operated as a branch office. The following year, a notice was posted in the local paper stating that J. Fleury's Sons Limited was submittng an application to surrender their Charter, which would formally disolve the independent Fleury firm. In April 1940, the decision was made to centralize all Fleury-Bissell operations in Elora and permanently leave Aurora, bringing with them 35 employees.

14. Downtown Aurora

Aurora Museum & Archives 2002.19.31a

c. 1910

Aurora's downtown 'skyscraper', located at the far left, is the Medical Hall. Completed in 1885, it was intended to house pharmacies and medical offices, as well as other businesses and community organizations. The pharmacist who commissioned the structure died of tuberculosis shortly after its completion, and it was sold to John Rutherford who housed various pharmacies in it until 1969.

* * *

The Radial Line into Aurora was one of three that radiated out from Toronto (hence the name), and probably first reached Aurora in 1899. The streetcars ran straight up the centre of Yonge Street to a station located where T.C.'s Burgers is today, just south of here.

The line was never profitable and only lasted until 1930. In Aurora, as in most North American cities, competition from cars, which were faster and offered more flexibility, drove the streetcars to extinction. Not without a touch of symbolism, the streetcar station was sold to Imperial Oil in 1930 and converted into a gas station.

15. The Town Hall

Aurora Museum & Archives 2005.28.95n

c. 1870s

This photo shows a group of people gathered in Yonge Street for a photo. To the left the building with the steeple was the Town Hall. Built in 1876 the Town Hall served a huge array of community functions, from fire hall to council chamber, farmer's market and auditorium. For decades much of Aurora's community life revolved around this Italianate-style building.

* * *

Historian Jacqueline Stuart lamented the apparent lack of interest in preserving a building of such obvious heritage value:

"There should have been a public outcry at the destruction of the old town hall: a good-looking building whose size and style were appropriate for one of the "gateposts" of the main business block of town- the towered United Church performed the same role across the street. For eighty years it had been where decisions, large and small, which had directed the town's course had been made. It was a landmark!

"There was no public outcry, if the local papers are to be believed. The publisher of the Aurora Banner made a few pro forma comments, and invited readers to share their memories of the old building. " There was only one respondent. "There was no photo essay about the last hours of the building, as the old bell was removed, the tower taken down, and the dignified brickwork reduced to rubble.

"Perhaps it was because at that time people were consciously looking forward to a bright, new, modern world, and were not interesting in being reminded of the old world, which in the memories of all adults in 1956 included at least one world war. Perhaps Aurorans were just realistic: the old building was held together with iron rods and had an awkward interior layout and for a long time had not worked as the town office."1

Endnotes

1. Aurora's Early Years

1. W. John McIntyre, Trinity Aurora: A Parish History. (Aurora: Trinity Church Committee, 1996), 8.

2. Jacqueline Stuart, An Aurora ABC: Stories from Aurora's Forgotten Past. (Aurora: Aurora Historical Society, 2016), 62.

2. The Public School

1. Stuart, 40.

2. Statistics Canada, "Census Profile: Aurora." Online.

3. Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada. "Kennedy, Thomas." Online.

4. Stuart, 40.

3. The Mechanics Hall

1. C.M. Turner, "Politics in Mechanics' Institutes 1820–1850." (Leicester University Research Library), Online.

4. The Town Park

1. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. "Blake, Edward." Online.

2. W.S. Wallace, "Edward Blake's Aurora Speech, 1874," Canadian Historical Review. Vol. 2, No. 3, Sept. 1921, p. 249.

5. The Queen's York Rangers

1. Stuart, 150.

6. A 'Genteel Family' Home

1. W. John McIntyre, Aurora: A History in Pictures. (Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1988), 19.

7. The Railway

1. N & H Mika, Historic Sites of Ontario. (Belleville, Ont.: Mika Publishing Company, 1974), 21.

2. Stuart, 103.

8. The Railroad Hotel

1. Jacqueline Stuart, "The Worst Place Inside the Corporation," The Auroran. May 16, 2018. Online.

2. Ibid.

9. Kindness of Strangers

1. Stuart, 104.

11. Horton Place

1. Greenhill, R., MacPherson, K. & Richardson, D. Ontario Towns. (Oberon Publishing, 1974), 59.

12. Queen's Hotel

1. Stuart, 104.

13. The Fleury Works

1. R.G. Dun & Company, Credit Reports Collection, Harvard Business School.

2. Ibid.

15. The Town Hall

1. Stuart, 149.

Bibliography

Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada. "Kennedy, Thomas." Online.

Dictionary of Canadian Biography. "Blake, Edward." Online.

Greenhill, R., MacPherson, K. & Richardson, D. Ontario Towns. Oberon Publishing, 1974.

McIntyre, W. John. Aurora: A History in Pictures. Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, 1988.

McIntyre, W. John . Trinity Aurora: A Parish History. Aurora: Trinity Church Committee, 1996.

N & H Mika. Historic Sites of Ontario. Belleville, Ont.: Mika Publishing Company, 1974.

R.G. Dun & Company, Credit Reports Collection, Harvard Business School.

Statistics Canada, "Census Profile: Aurora." Online.

Stuart, Jacqueline. An Aurora ABC: Stories from Aurora's Forgotten Past. Aurora: Aurora Historical Society, 2016.

Stuart, Jacqueline. "The Worst Place Inside the Corporation," The Auroran. May 16, 2018. Online.

Turner, C.M. "Politics in Mechanics' Institutes 1820–1850." Leicester University. Online.

Wallace, W.S. "Edward Blake's Aurora Speech, 1874," Canadian Historical Review. Vol. 2, No. 3, Sept. 1921.