Walking Tour

The Story of Sparwood

Coal in the Crowsnest

Natalie Dunsmuir

Since its beginnings as a small lumber settlement, the town of Sparwood has followed the risings and fallings of resource development in the Crowsnest Pass. Its fate and fortune has been determined by the coal industry, which has shaped the region profoundly. Yet before coal was discovered and settlers and miners first came to Sparwood, the local Ktunaxa First Nations people travelled through the area each year, following the seasons and the movement of the bison on the nearby plains. Their history in the area stretches back for over 11,000 years.

In the late 19th century, the discovery of rich coal lands brought crowds of immigrants, businessmen, and miners to the area. Four towns were established and grew: Michel, Natal, and Middletown, located in the direct vicinity of the mines, and the town of Sparwood, several miles away and originally far quieter than the other two bustling coal towns.

Route

In this tour, we will learn about the interwoven stories of these three towns and how they grew and fell with the fortunes and collapses of the coal industry. At Stop 1, beside the "Welcome to Sparwood" arch on Red Cedar Drive, we will introduce the town of Sparwood and explore its early history and what was located here before it was established. Then, we will travel along Aspen Drive to the Sparwood Museum, where we will learn about coal itself and its role in industrial development. At Stop 3, farther along Aspen Drive, app users can admire the "Terex Titan, the largest tandem axle dump truck in the world, and embark upon the story of coal in the Crowsnest Pass.

Stop 4 takes visitors to the Sparwood Mining Monument to learn about the dangers and difficulties of early coal mining and the many tragedies and disasters which have befallen miners in the region. Stops 5, 6, and 7 continue along Aspen Drive and dive into the rising fortunes of the towns of Michel and Natal. Stops 8 and 9 continue this theme, as well as examining some of the challenges faced by these communities. Stops 10, 11, and 12, which travel towards downtown, chart the fall of Michel and Natal and the rise of Sparwood in their place. The final three stops of the tour continue to explore downtown Sparwood as they look into the town's growth in the latter part of the twentieth century and the changes to the mining industry which have kept it a major part of the community's economy today. The tour ends on Centennial Square Road a few blocks away from where it started.

This project was made possible through a partnership with the Sparwood Museum and Archives.

1. Sparwood's Founding

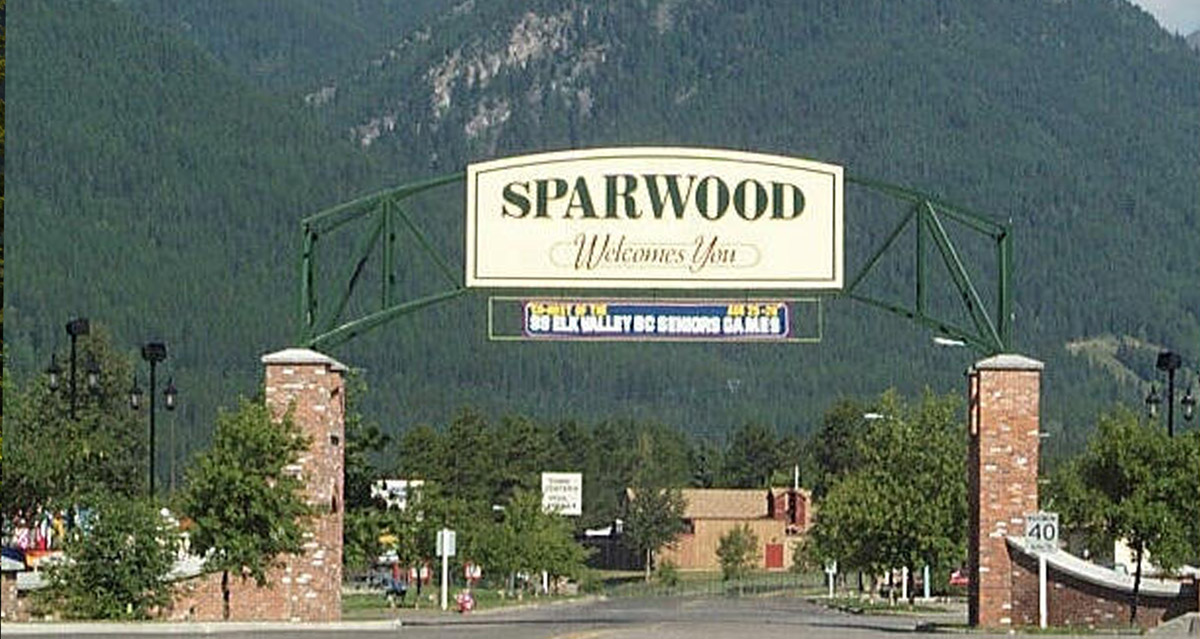

ca. 2000s

This archway has welcomed visitors and residents alike to Sparwood for many years. It stands against a backdrop of the mountains which give this community its character and livelihood. These majestic mountains were formed millions of years ago and are part of the Rocky Mountains which stretch nearly 5,000 km from north to south.

* * *

Europeans first came to the region in the late eighteenth century. The first of these travellers were surveyors and fur traders such as Peter Fidler, a surveyor who worked for the Hudson's Bay Company and was the first European to journey through the Kootenays. European settlement during this time, however, was scarce. It wasn't until a hundred years later, in the 1880s, that interest in the coal in the region began to grow, and Europeans first began to settle in large numbers in the Crowsnest Pass and the Elk Valley.

When they did, however, it was not the town of Sparwood they turned to, which for many years after the establishment of the coal mines in the Elk Valley remained little more than a lumber mill and small collection of homes. The name Sparwood itself was first attached to a railway stop in the area where the town sits. It was so named not for coal but for lumber: the trees in the region were used for "spars", the poles used in shipbuilding to create masts. A post office first opened in Sparwood on April 1st of 1903, but its lifespan was short—it closed in September of 1916. Sparwood was located several kilometers away from the newly opened mines, and this distance slowed its growth while the towns of Michel and Natal to the east, much closer to this key source of employment, began to flourish.

2. The Lure of Coal

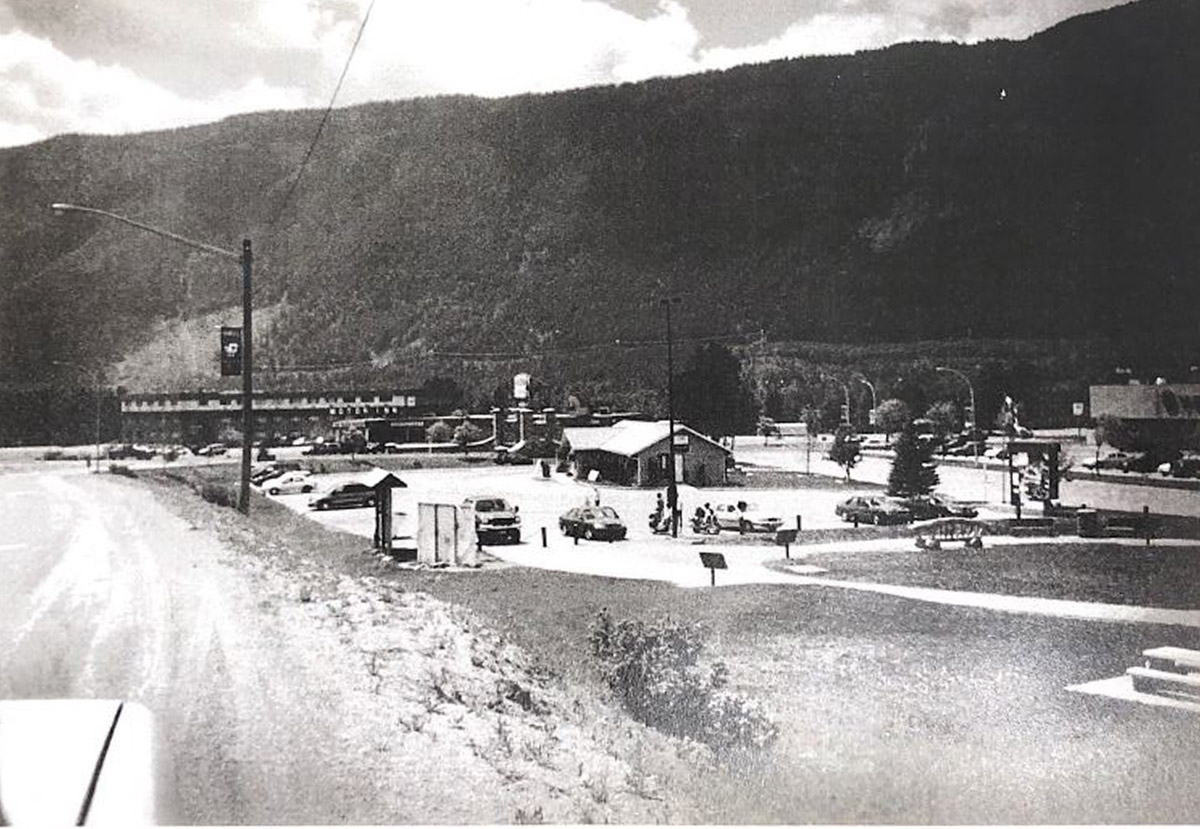

ca. 1990s

The Sparwood Museum, pictured here, is an important part of the community, documenting and sharing the stories of not only the town of Sparwood but the towns of Michel and Natal and the history of coal mining in the Elk Valley. The museum is run by the Michel-Natal/Sparwood Heritage Society, which was established in 1985.

* * *

Coal is a nonrenewable resource, and the process of its formation takes millions of years. Yet the burning of coal to create energy is one of the largest sources of electricity generation in the world, and coal itself is the most abundant fossil fuel on the planet.1 The coal which is mined in the Crowsnest Valley is bituminous coal, which is a high grade of coal formed under immense pressure and heat between 100 and 300 million years ago. Coal which is younger or has undergone less pressure is typically of a lower quality, creating less energy when burned and producing more ash.

Coal has been used by humans for thousands of years. The Romans and Aztecs, for example, used coal to heat public baths and as ornaments and fuel respectively.2 Yet this fuel source did not take centre stage in the economy until the Industrial Revolution, when it became a core factor in the rise of industry and was used to create steam to power factories, machineries, trains, and ships. Coal was a central part of Canada's industrial revolution from the mid-19th Century, just as it had been in the British industrial revolution which began there a century earlier. It was used not just to heat people's homes but to power factories, sawmills, smelters, and mines. Perhaps more crucially in Canada's story, coal was also to power trains, whose development radically altered the course of Canadian history. The coal of the Crowsnest Valley was a large part of this story.

3. Birth of the Coal Industry

ca. 1990s

This colossal truck, known as the 'Terex Titan', was the largest of its kind in the world. It is a tandem axle dump truck, and while it now serves as a tourist draw, it was once an important part of Sparwood's mining operations. The Titan was built in 1973 by General Motors of Canada and arrived in Sparwood five years later, disassembled and riding on the backs of eight flatbed railway cars. It worked in Sparwood's open-pit coal mines until it was retired in 1990. The truck could carry immense loads of up to 317 metric tons and could travel at speeds of nearly 48km per hour when fully loaded. High fuel costs, however, ensured that only one such truck was made, and after the vehicle was retired, it was donated to the town of Sparwood as a monument to the region's mining and to attract visitors.

* * *

But development was coming. In 1884, a geologist with the Geological Survey of Canada, George Mercer Dawson, travelled to the area, and his 1886 report documented the coal seams in the Elk Valley. By the next year, the eyes of industry had turned to the valley. Colonel James Baker, who was a prominent landowner in nearby Cranbrook, set his sights on the region, along with his business partner William Fernie, former Gold Commissioner, and a syndicate of other businessmen. They wasted no time in getting started, and by 1896, the group had acquired 250,000 acres of coal land in the Elk Valley.

Yet ironically, the business could not begin until a railway was constructed. The coal industry might have fuelled Canada's railways, but it also relied upon them. By 1896, Baker's and Fernie's syndicate had acquired a charter from the provincial government for a railway that would stretch from the Elk Valley to the West Kootenays, where smelters would allow for the processing of the Valley's coal. Yet money was tight in the railway business and construction was expensive. It was not until the next year, when Canadian Pacific Railway president William Cornelius Van Horne struck a deal with the Dominion Government, that construction could begin. The government would give the CPR $11,000 per mile of track laid down, and in exchange would receive 50,000 acres of coal land and the promise that coal would be supplied to it at a reasonable price. It was a common form of exchange between the government and railway companies in those days.

With these subsidies secured, the first mines opened in the Elk Valley, and in 1897, 10,000 tons of coal was produced. The railway was completed the next year, spurring the industry on further as the markets available to it expanded.

4. The Dangers of Mining

Outdoor Exhibit

This monument stands to commemorate the many people who were lost in mining disasters in the Sparwood area throughout the years. The coal mines of nearby Michel, Natal, and Middletown may have offered employment for hundreds of men, many of whom were recent immigrants to Canada, but they were also the site of many tragedies. Coal mining was dangerous, fraught by hazards both big and small, and a total of 181 men were killed in mining disasters in the Elk Valley throughout the years.1

* * *

Mines were cold, wet, and dark, and the air was often dangerous to breathe. Falling rocks were a constant danger, as was the ever-present threat of an explosion. Coal itself contains high quantities of methane, and pockets of methane can be ignited by the smallest spark or heat source and cause enormous explosions. It was estimated in a 1920s study that the mines in the region produced 3,640 cubic metres of methane gas per ton of coal mined.2

Coal dust also made the air toxic to breathe, and long exposure to it throughout the years could lead to the development of "black lung", or pneumoconiosis, a disease which leads to lung impairment, difficulties breathing, coughing, and, often, fatality. The danger was such that the mines in Michel, Natal, and Middletown included large ventilation fans which sucked toxic air out of the mines and replaced it with fresh air from the outside world.

The conditions under which miners laboured for many years were encapsulated in 2017 by Ewan Gordon, a retired miner who well remembers the dangers of the mines: "You were kinda listening to the earth talkin' to you, hoping it wasn't gonna fall on your head. You felt a lot closer to your maker when you were listening to the ground crack around you."3

Men died in the mines in Michel-Natal almost every year. Some years were worse than others however. In 1904, seven miners died in an explosion and two more were injured. In 1916, 13 men were killed. In 1938, three more died in an explosion. And in 1967, an explosion killed a total of 15 miners, along with injuring ten more. The Balmer North Explosion shocked the small communities: "A pall of grief and disbelief hangs over this community and the entire coal mining area of the Crowsnest Pass on both sides of the B.C. - Alberta border today. In Natal groups of men stand in silence on the street corners, women walk in hushed groups carrying food between homes and children wait news of the loss of relatives and men they knew well."4

As one survivor of the Balmer Explosion said, “We said every day, we go in but we’re not sure if we’re coming out. We knew it was gonna be happening…There was too much dust…A mine is a mine. You go in, you never know if you’re going to come out.”5 And yet mining continued in the Sparwood area, and miners returned underground over and over again. Gradually, improvements in technology increased the safety of the job, and today, the large, open-pit mines in the region have few of the same hazards of the old, underground mines from the early 20th Century.

5. Michel, Natal and Middletown

ca. 1930s

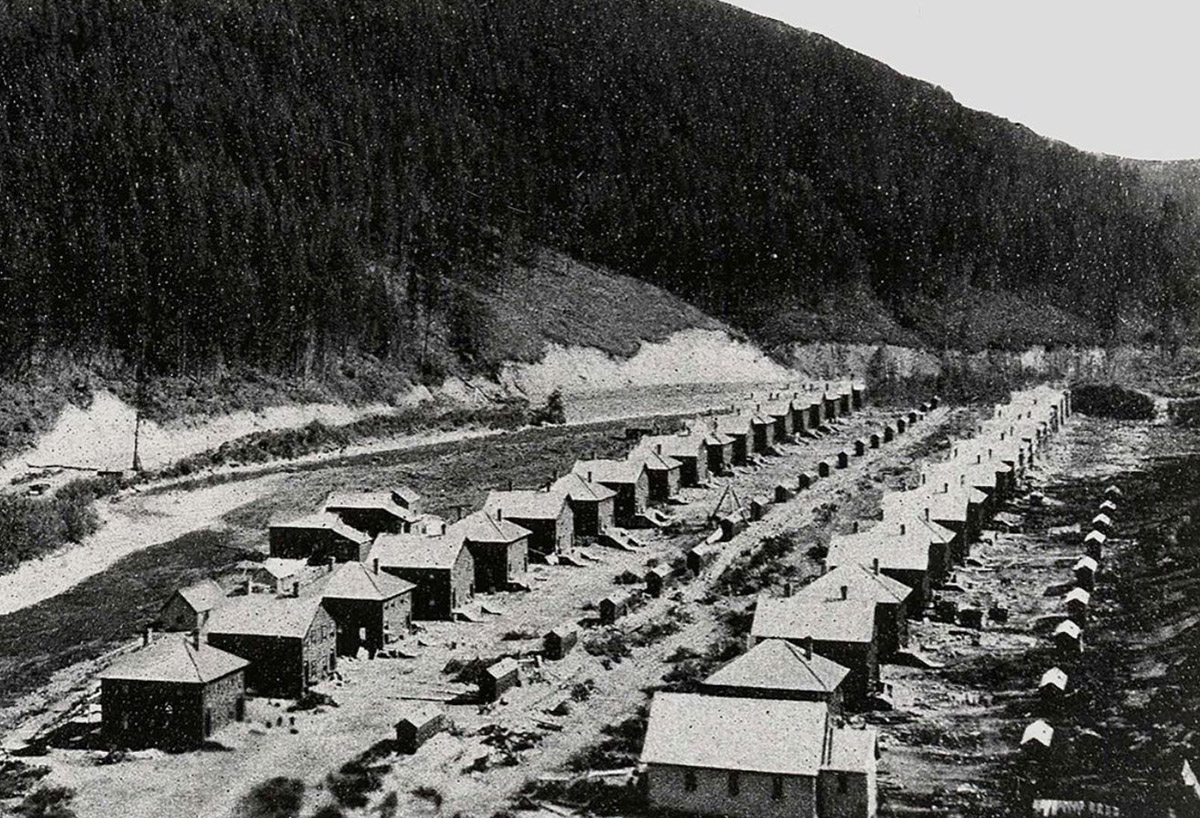

This photo from the 1930s shows the town of Michel in winter, where the miners of the Elk Valley lived and worked. Michel was one of three small communities nestled in the vicinity of the mines and largely inhabited by those who were employed there, along with their families. The small towns came into being towards the end of the nineteenth century and slowly grew in size during the first several decades of the twentieth century.

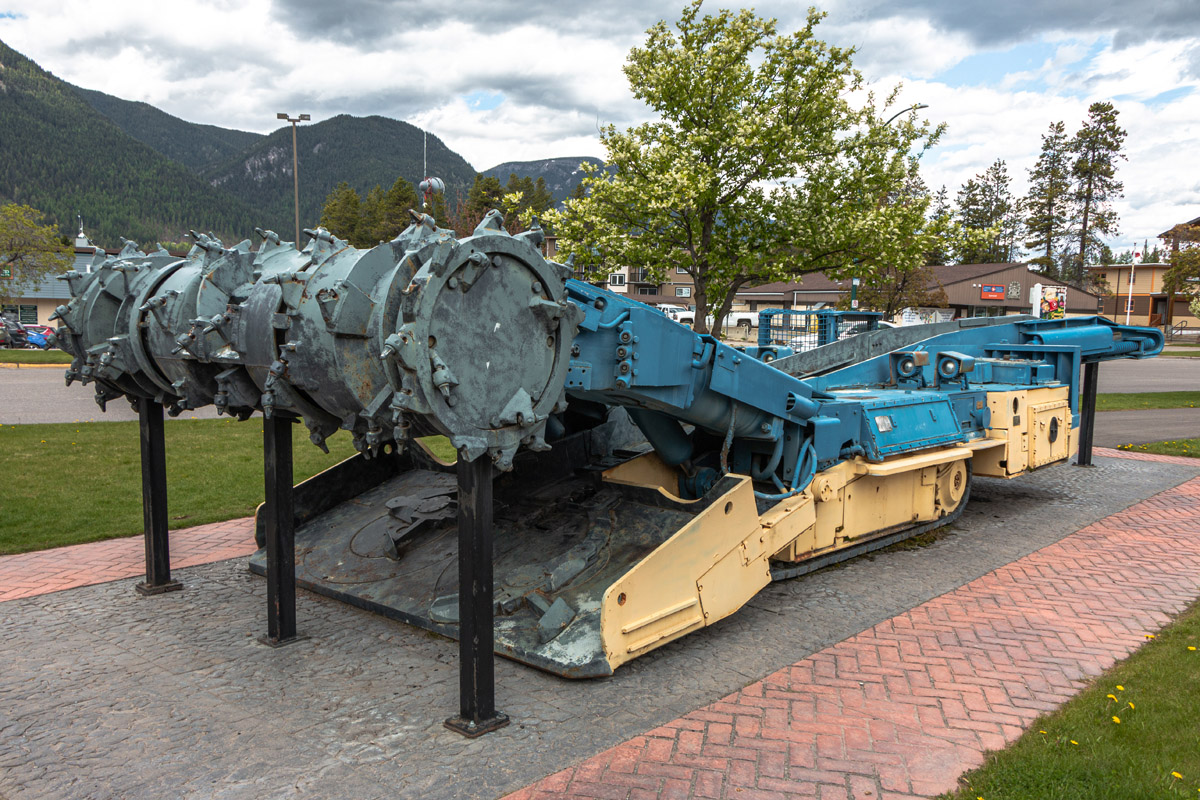

You are currently standing in front of a rock saw. Resembling a large chainsaw, a rock saw can break through tough stone and was often used in mining. It joined many larger, more powerful tools that became a part of mining as the industry evolved throughout the twentieth century, leaving behind the era of small hand picks and shovels.

* * *

Michel

The town of Michel was first founded at the end of the 19th Century as a home to the miners flocking to the Elk Valley in the late 1890s. This small community, located off of where Highway 3 now runs, was centred on the mines of the Crowsnest Pass Coal Company, which employed most of the population. Its name came from Chief Michel, an important member of the Ktunaxa First Nations.

The town originally consisted of 60 single family dwellings and three company-owned boarding houses.1 As the mines grew, the town's population grew as well, numbering over 1,000 by 1907. The Michel Hotel and a 19-bed, three-storey hospital were built as well.

Natal

The town of Natal began to take shape nearby in 1907. It was originally known as "New Michel", but was later renamed "Natal" after a province in South Africa. While Michel remained the business centre of the valley, Natal took on a reputation as the cultural centre, with three hotels, an opera house, a movie theatre, and even, eventually, a basketball hall.

Middletown

The smaller community of Middletown was established between these other towns, hence the name. “In Middletown, there was room for three unequal rows of houses, bordered by Michel Creek on one side and the highway, railroad, some of the coke ovens and a service road on the other. At the eastern end of Middletown were located the slag dumps."2

Still, these three towns developed a strong sense of industry and community. Residents were bound together by their shared reality, and the three settlements were places of life and vibrancy.

6. Life in Michel-Natal

ca. 1940s

This photograph from the 1940s shows the community of Middletown, which was located between Michel and Natal. It was largely a residential area where workers of the mine made their homes. Despite the small size of these mining towns, life in Michel, Natal, and Middletown was rich and busy.

The intimidating piece of machinery you stand in front of was used in mining to break open and crush rocks. Like the rocksaw in the above tour stop, this tool was part of the technological change which overcame mining in the twentieth century, creating an industry which relied on heavy machinery in the place of hard manual labour.

* * *

The population itself was a diverse one. Immigrants came from all over North America and Europe to work in the mines and brought their families with them. Miners born in Canada worked alongside Americans, Brits, and a large population of Italians, among others. There was a "Little Italy" neighbourhood and a "Little Chicago" neighbourhood in Michel-Natal.1 The shared experiences led to a shared sense of camaraderie between these diverse populations.

Community organizations were an important part of the town spirit. They gave residents a chance to socialize, let off steam, and work to improve their communities. Events and gatherings were an important way to stay connected and happy in remote communities such as Michel-Natal. There were dances, sports' games, dinners, picnics, and charity events. Local clubs and lodges helped to fundraise for local charity efforts as well as for larger organizations such as the Canadian Cancer Society. Sports such as soccer, baseball, and basketball gave a physical and social outlet to the miners and their families as well.

Despite the challenges of life in these towns, the residents created a community they could be proud of, and the demolition of their homes in the late 1960s must have been difficult. Neighbourhoods were bulldozed and buried, and the tight-knit relationships that had been formed were scattered. Most of the clubs and organizations which had been so important in Michel-Natal came to an end. Memories and photos are now the only thing that remain from these fledgling towns.

7. The Coke Ovens

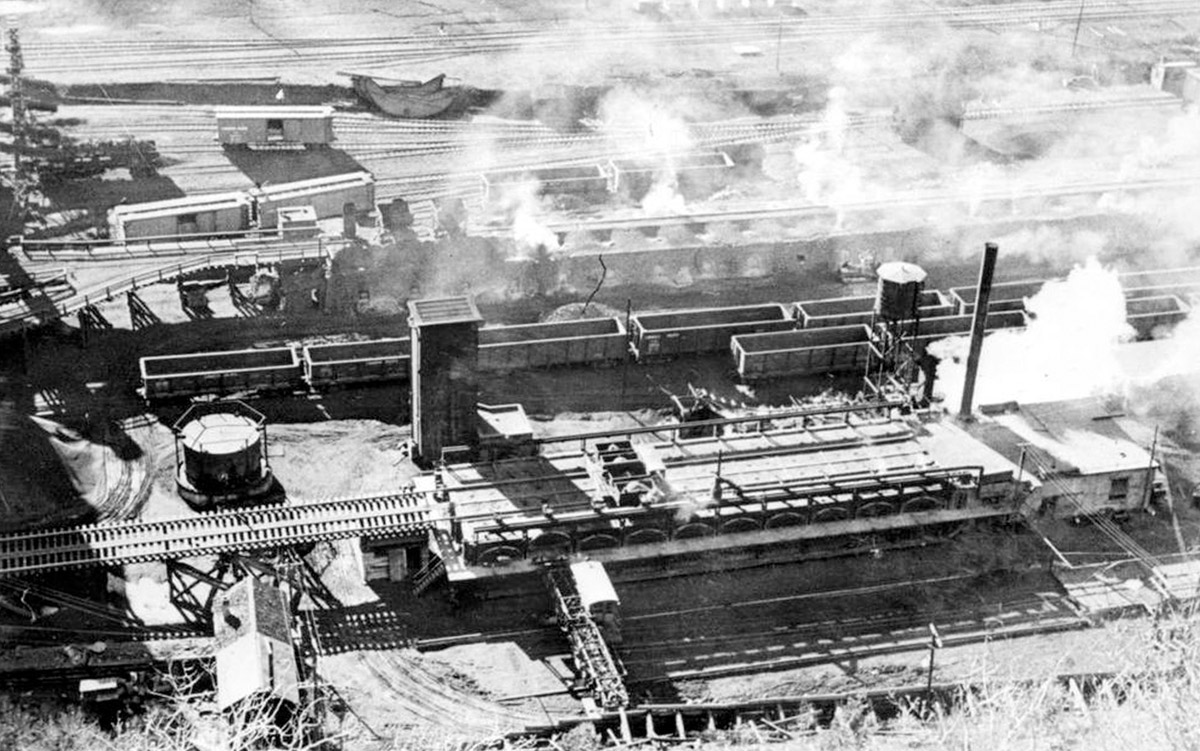

ca. 1940s

This aerial photo shows a crucial part of the mining industry in Michel-Natal: the production of coke in large coke ovens. In the Elk Valley, there was a second side to the coal industry which kept many in the town employed. Coal was not only mined and transported here, but it was also transformed into coke, a substance used in smelters and crucial in the production of steel. Michel-Natal's coke ovens were a key part of the community's economy.

You are standing beside a "joy loader", a piece of mining equipment which was used for loading material such as ore, rock, and coal. This well-worn piece of equipment was likely used in the mines in the Elk Valley during its years of operation.

* * *

Not all forms of coal are suitable for such a high-intensity process, but the coal mined in the Elk Valley and Crowsnest Pass region was highly prized for coke production—more so than the coal mined on Vancouver Island, the other main coal production area in British Columbia. Not long into the lifespan of the Crows Nest Pass Coal Company, coke became a major focus. Each year, new ovens were built and opened, and production increased. Coke ovens were located throughout the region, at Fernie, Morrissey, Hosmer, and, of course, Michel-Natal.

Coke production required a lot of coal, and much of what was mined at Michel-Natal was then directed to the nearby ovens. To produce a tonne of coke required 1.43 tonnes of coal, and by 1904, 54% of the coal mined here—350,800 tonnes—was being transformed into coke.2 From there, it travelled to steel smelters in Nelson, Trail, and across the US border in Northport.

The coke ovens were kept busy at Michel, and many of the town's residents worked to keep them running. It may have been a job that took place above-ground, but it was still dangerous work. The coke ovens were extremely hot, and, like coal, emitted toxins into the air which could have extremely damaging long-term effects. The ovens sent a mixture of dust, gas, and vapour into the air which often included such substances as arsenic and cadmium, carcinogens linked to cancer.3

Over time, Michel became the centre of coke production in the region, with 464 ovens in operation, more than anywhere else in the Crowsnest Pass. Production of coke peaked before World War I, after which the industry entered a period of slow decline. Nearby, the smelters at Grand Forks and Greenwood closed their doors, reducing the nearby available market for coke. By 1922, Michel's ovens only produced 61,497 tonnes of coke, using only 11% of the coal produced that year.

Still, coke production continued to be a major part of Michel-Natal's economy for several more decades. In 1952, the old ovens were demolished, but they were then replaced by 52 new, more modern and advanced ovens, and these did not shut down until the 1970s.

8. Pollution in Michel-Natal

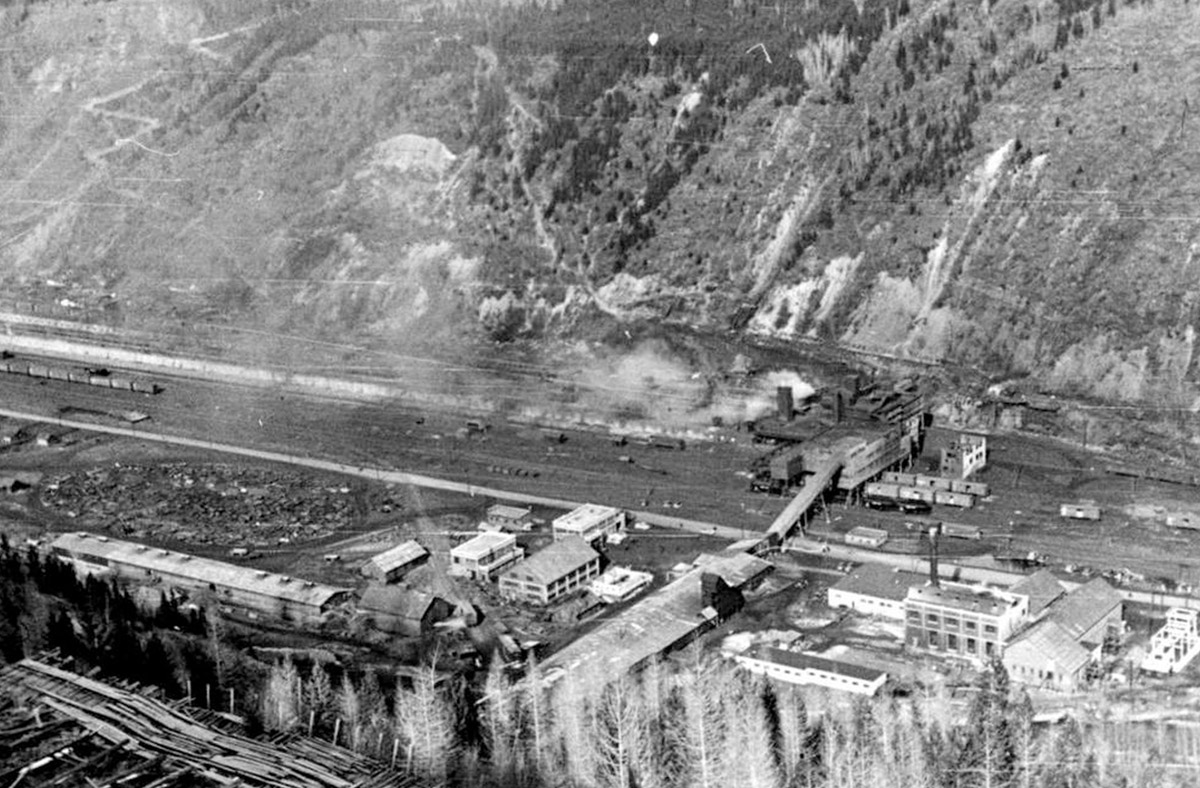

ca. 1940s

This aerial photo dates from the 1940s and shows the mine and tipple at Michel-Natal during its operations. Here, the ore mined by the many miners of the town was processed and then loaded on railway cars, bound for markets in both Canada and the US. Note the smoke wafting upwards and sideways from the mine tipple. Increasing awareness of the damage caused by air and water pollution in the 1950s and 1960s meant pollution became a central issue in these communities.

You are currently standing beside a "shuttle car", another vehicle used in mining to load and transport earth, ore, and rock.

* * *

In the 1960s, a shift in the coal markets worldwide only increased the pollution levels in Michel-Natal. Previously, the Crows Nest Pass Coal Company's major buyer had been the Canadian Pacific Railway, which burned lump coal. When this transportation system evolved away from coal-powered trains, the destination of much of Michel-Natal's coal became the global steel industry, which required coal of a very fine texture—a texture which led to an increased dispersal of coal dust.1

Coal dust is not just an eyesore: it can also lead to many dangerous and often fatal diseases. Exposure to coal dust for long periods of time can lead to a number of pulmonary diseases, which affect the lungs and respiratory system. In particular, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affected many of Michel-Natal's residents, causing coughing, difficulties breathing, and sometimes the development of more serious conditions such as heart disease and lung cancer..2

It wasn't only the coal dust which caused pollution in Michel-Natal, although that was certainly the main cause. In Natal, the water was contaminated by the septic system. The problem was a difficult one to solve, and would have taken a great deal of money to do so. With neither clean air to breathe nor clean water to drink, the residents of Michel-Natal began to consider new solutions.

9. The Mid-20th Century

Memorial

This stone archway memorializes the Michel and Natal residents who fought and died in the First World War, Second World War, and Korean War. It was erected shortly after the First World War by Michel's branch of the Royal Canadian Legion. It includes three base stones that honour those who fought in three of Canada's biggest battles: Ypres, Passchendale, and Vimy Ridge. Later, a new stone was added for the Second World War, and a plaque memorializing the Korean War was affixed to the cenotaph in the 1950s. The cenotaph originally stood in Michel-Natal, on the grounds of the public school. However, it was moved in the 1960s, during the lengthy process of relocation from Michel-Natal to Sparwood.

* * *

In the first half of the twentieth century, the decline of the coal market was slow, with some fluctuations. By the 1950s the industialized world was turning away from coal. Oil and gas began to take its place as the main energy sources across many industries. including the railways, which for decades had served as the Crows Nest Pass Coal Company's main market. The Canadian Pacific Railway, for instance, first began to experiment with diesel-fuelled locomotives in 1937, and by the 1960s had transitioned entirely away from coal. Likewise, the Canadian National Railway purchased more than 100 diesel-run locomotives in 1952.2 By the 1960s, BC's coal industry had lost its main buyer.

Hydroelectricity also threatened the prosperity of the coal industry. Increasingly, this clean energy source was being used to power domestic households and more, replacing coal as a power source. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, major hydroelectric projects were constructed across BC, and today, 87% of the province's electricity comes from hydro.3

The coal industry in the Crowsnest Pass faced extinction, unless new markets could be tapped. The Crows Nest Pass Coal Company went searching farther afield. In the early 1960s, they began to ship coal to the steel manufacturers of Japan, and this new market only broadened as the decade progressed.

In 1967, Kaiser Resources, based in California, began the process of acquiring Crows Nest Industries, formerly the Crows Nest Pass Coal Company. They also began negotiations with Japanese businessmen to sign long-term coal contracts. By the following year, both business transactions had taken place: Kaiser now owned the mining operations in Michel-Natal, and Japanese steel manufacturers had signed coal contracts which ensured the survival of BC's coal industry into the twenty-first century.

10. The End of Michel-Natal

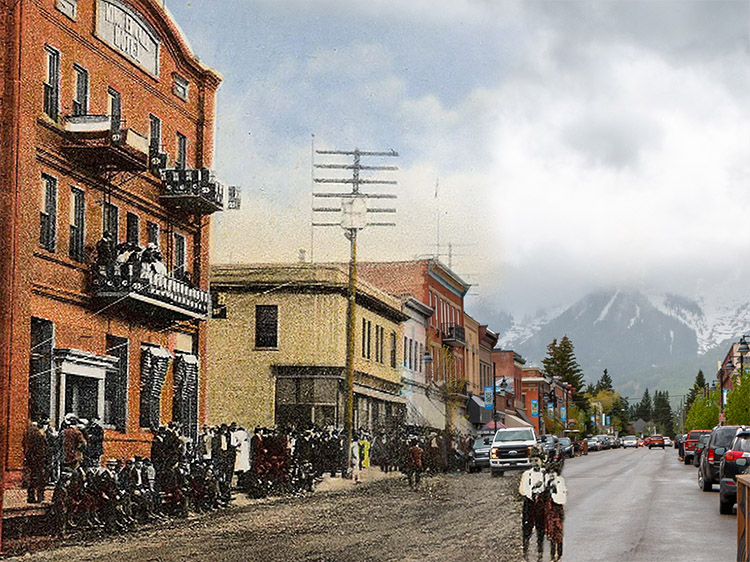

Fernie & District Historical Society FMP_00008

ca. 1930s

This photo, taken in the 1930s, shows many of the houses of Michel-Natal where the miners and their families made their homes. Bodie Creek is to the left. Today, this area is empty of any sign of human habitation, a green strip of grass and trees located beside Highway 3. Many factors contributed to the ultimate abandonment and demolition of the towns of Michel, Natal, and Middletown. The process of relocating these communities was long and filled with controversy, and while residents were at first hopeful, the long, drawn out process and heavy hand of the provincial government left many with feelings of bitterness.

The massive piece of mining equipment which you are currently standing beside is a belt conveyor, a crucial piece of equipment in Sparwood's mining operations. It was used to transport massive amounts of ore throughout the mines.

* * *

Presented with such a plan, the residents of Michel-Natal agreed nearly unanimously. In 1965, the councils of both Natal and Sparwood agreed without reservations, and a district plebiscite in April of 1966 passed with 95.6% support.1

The reason for this overwhelming support was simple: pollution in Michel-Natal had become nearly intolerable. Coal dust choked the skies and settled across the ground, and the water in the town of Natal had become contaminated. Women, in particular, were in favour of the relocation plan. They were the ones, after all, who toiled daily to attempt to fight the pollution and dirt, cleaning endlessly to create safe homes for their families.2

The provincial government had reasons for encouraging the relocation as well. For one, 50% of the funds for the move would not have to come from them—the federal government's National Housing Act would cover half of the relocation. And for two, the plan allowed the government to continue to build British Columbia's reputation as a beautiful, natural, and innovative place. Currently, travellers from the rest of Canada to the east drove past Michel-Natal along Highway 3 almost the moment they entered BC. Their first impression of the province was of “a devastated, run-down, mining community.”3 Removing this town would remove this negative first impression.

Initially, the relocation process seemed as though it would be straightforward and uncontroversial. The stage was set for an easy transition from Michel-Natal to Sparwood. The Crows Nest Coal Company agreed on the move, the government supported it, and the residents had voted in its favour. Even the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation called the plan "visionary" and "experimental".4 A feasibility and planning study which was undergone in 1966 was adamant in its support for relocation, and in that same year, the new District Municipality of Sparwood was created to smooth the transition.

And yet, things did not go as planned, and the relocation process was anything but smooth. Rising tensions and controversies marred the process, and it would not be until 1978 that the communities of Michel and Natal were finally demolished. The relocation was the end of an era, and for many, the end of their stay in the Elk Valley.

11. Moving to Sparwood

ca. 1970s

In this image from the 1970s, a parade float travels through downtown Sparwood, pulling a recreation of the Terex Titan, one of the largest trucks in the world and a local landmark that honours the community's mining history. Throughout the 1970s, Sparwood gradually became the home of many of those miners and their families who had once lived in Michel-Natal. The transition, however, was anything but smooth. A change in the ownership of the mines of Michel and Natal led to another year of negotiations, in which both the mine owners and the provincial government threatened to abandon Sparwood as a relocation site in favour of Fernie instead. It took immense protest efforts on the part of local residents to ensure their relocation to Sparwood, and even then, many community members found themselves unable to afford the move. With the demolition of the town of Michel-Natal, these residents were forced to leave the Elk Valley entirely.

* * *

This announcement was met with a wall of opposition, particularly from a group of thirty-five local women who suggested protest actions ranging from suing the coal company to marching on Victoria. The chair of Natal's council, Orlando Ungaro summed up the town's feelings when he said, “When industry hampers a community, it is time for the community to take a stand."1

This stand paid off. After a year of protest, both the provincial government and Kaiser reversed their position, and the move to Sparwood began to take place at last. For many residents of the area, the decision came too late. The Regional District of the East Kootenay had begun the process of buying the houses of Michel-Natal residents a year before, and by 1968, they had purchased over 150 houses. The people who had owned these houses left town, and without the completion of Sparwood, many did not stay in the Elk Valley.

Even after Sparwood was completed, many miners and their families could not afford to move there. The money they were given for their homes in Michel-Natal was far below what was required to buy a property in the new town. Exacerbating this problem was Kaiser's desire for a complete demolition of Michel-Natal to make room for new offices and warehouses. Many residents had nowhere to go, and yet staying behind was becoming impossible. Demolitions began in the early 1970s, and Kaiser evicted tenants living in coal-company houses in Michel, regardless of whether or not they had managed to secure other accommodation in the valley.

While some houses were simply picked up and moved to Sparwood, most were destroyed. As a way of marking which houses could be saved, large 'X's and 'O's were spray-painted onto the sides of buildings—the 'O's could be saved, while the 'X's were to be destroyed. By 1978, the final buildings of Michel-Natal were torn down and municipal services officially came to an end. All that remained standing was the Michel Hotel, which stood as a marker of the old town until 2010, when it too was demolished.

The process of relocation had been messy and, for many, painful. It stretched on for over a decade, leaving many residents feeling betrayed and abandoned. “The organizers of the urban renewal project treated everyone like a statistic rather than consider the human needs of special social classes.”2

12. The Difficulties of Relocation

1966

This photo from the 1970s shows the communities of Michel-Natal from the air just years before they were demolished. The image shows both the residential and commercial sections of the small town, along with the mines. It was a landscape deeply familiar to many, but one which would not exist for long after this picture was taken. Despite the initial positivity surrounding the relocation of Michel-Natal, negotiations over land and finances drew on, leaving residents feeling betrayed by both the provincial government and the Crows Nest Coal company, who were accused of putting corporate interests in front of the needs of the community.

The mural you stand beside celebrates the history of mining in the Elk Valley, showing some of the many miners who spent their lives toiling in Sparwood's mines.

* * *

The coal company attached new conditions to their willingness to make the Sparwood land available to their workers and their families. For one, they wanted to be exempt from municipal taxes, a concession which, if granted, would make it nearly impossible for the District Municipality of Sparwood to find enough funds for relocation. And perhaps even more contentiously, the company also wanted to be exempt from any bylaws that would restrict pollution in the District.2

Negotiations drew on for long months—months in which the residents of Michel-Natal were left to deal with the pollution in their town: "We wait week by week for news of something to happen better for us, but alas, no one seems to be interested in us – while all the time the dust and the smoke becomes worse, enveloping all and sundry."3

The provincial government at first accepted both of Crows Nest Industries' conditions, but they later rejected the second after considerable pushback from the town of Sparwood. As for financing, the tax concession was granted, and the nearby District of Fernie was brought into the project to help with funding. The Sparwood Council, unwilling to agree to this financial plan, was told that they either accept the new financial terms or witness “the entire project be dropped.”4 Accordingly, in March of 1967, they agreed. Two months later, Crows Nest Industries also accepted the new agreement, offering to sell 400 acres of land for the development of Sparwood. The relocation plans seemed to be back on track.

13. The New Town

ca. 1940s

The Michel Hotel, photographed here in the 1940s, was a large, three storey building which stood in the Elk Valley for over eighty years. The hotel was the last remaining building in Michel-Natal and stood alone for years, marking the site where the town used to stand. It was demolished in 2010 by Teck Coal, the current owners of the coal mines near Sparwood. The demolition took place after the building was abandoned in 2005.

You are currently standing beside a minecart, an iconic and crucial staple in the mines of the Elk Valley. Minecarts were used by miners to push ore throughout the tunnels of the mines.

* * *

After relocation, the town took on a new character. It was a diverse community, a mix of the original inhabitants and the newly relocated miners. In addition to these two groups, Kaiser's mine expansions meant the arrival of hundreds of new employees.

The official opening of the new Sparwood townsite after the relocation occurred on June 21, 1970. It was attended by many of the people who had worked so hard to ensure the relocation project met with success. The town was blessed by Natal Catholic priest Father Leslie Trainor. Orlando Ungaro, who in his role as mayor of Natal had played an instrumental part in the relocation process, also spoke.2

Many people built the new town of Sparwood together, but one person stands out, and is today considered a key founder: Loretta Montemurro. Montemurro began her career in local government in 1961, becoming the clerk of the Village of Natal. When the District Municipality of Sparwood was created in 1966, she was appointed the chief administration officer and treasurer for the new town. The new office for the District of Sparwood contained only three people: Loretta and two assistants.

In a 2013 interview just a year before her death, Loretta summed up her crucial involvement in the creation of Sparwood: “I had my hands on everything. I believed in giving out work, in delegating, but always in control."3 Loretta remained in her position in Sparwood for 35 years, until her retirement in 1995.

14. A Changing Industry

ca. 1970s

This photo dates from the 1970s and shows the Marshall Wells store during a parade through downtown Sparwood. Once relocation was complete and the new town had opened, residents began to make their new community home, with parades, celebrations, and other community events. The Marshall Wells store is no longer in operation, and the building currently houses the offices of Teck Resources Ltd, the current owners of the mining operations surrounding Sparwood.

* * *

Open-pit mining involves digging wide benches into the soil to extract resources. As opposed to creating a tunnel down to the coal, miners simply remove all of the earth which is on top of the coal seams, allowing the coal to be harvested in the open air. Dirt and rock is removed through excavation, drilling, and, occasionally, blasting. Waste rock is piled into large waste dumps. Open-pit mining, therefore, requires more land than underground mining, and has a much greater effect on the landscape. After an open-pit mine is closed, an extensive rehabilitation process must be undergone to attempt to minimize the environmental damage.

Yet open-pit mining is far safer than the underground mines of the early twentieth century. Workers no longer face the risks of rock falls, explosions, bad air, and tunnel collapses, and therefore, worker casualties have largely become a thing of the past. Labour is also far more mechanized and involves much smaller crews. Much of the mining operations are undertaken by massive trucks, bulldozers, and rock scrapers. Technology is now at the core of coal mining, and it allows for the movement and production of far more coal than could be extracted in the early days of mining.

15. Today's Sparwood

ca. 1970s

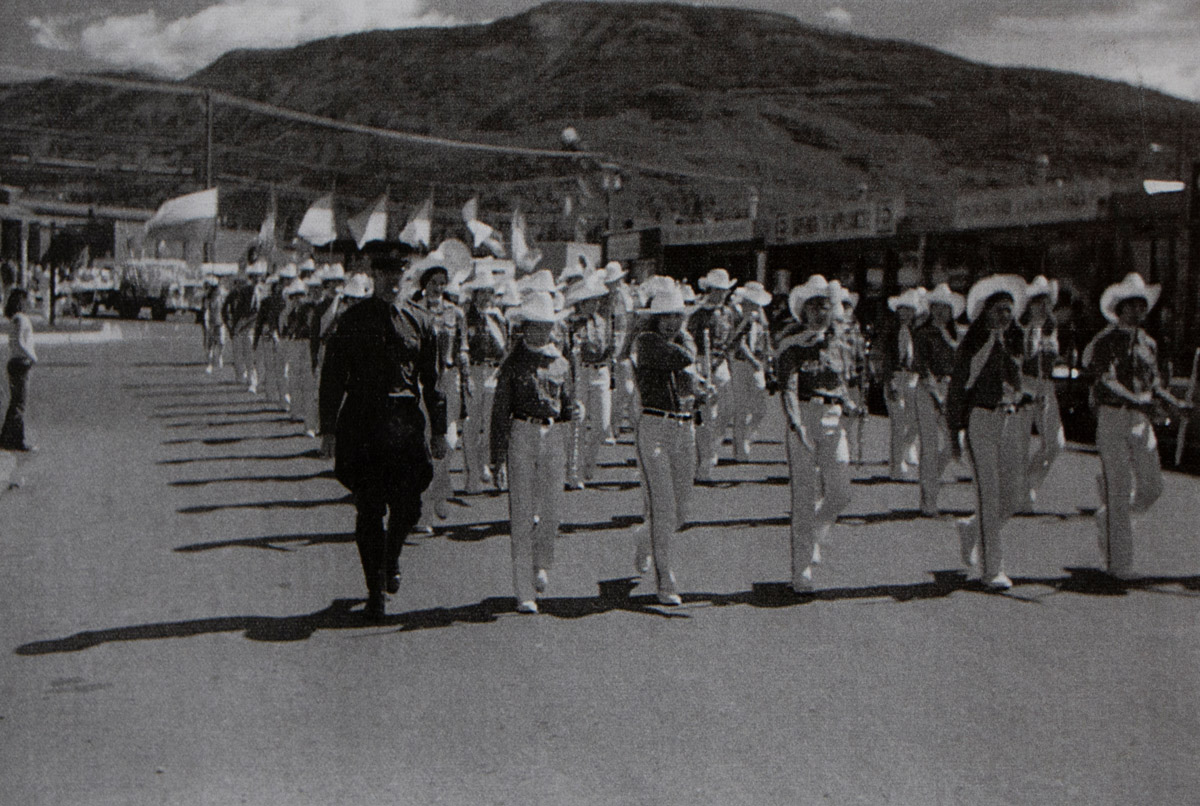

This photo from the 1970s shows another parade in downtown Sparwood, as a marching band in white hats plays along Centennial Street. A police officer marches with them on the left. Throughout the latter part of the twentieth century, Sparwood continued to grow and evolve, facing new challenges as it adapted to the modern world.

* * *

Yet dropping coal prices and market fluctuations in the 1980s led to an uncertain economy in Sparwood. In 1992, Westar Mining, formerly Kaiser Resources, filed for bankruptcy after closing its Balmer Mine near Sparwood in May due to labour unrest and mounting debt. The over 1,000 members of the local branch of the United Mine Workers Union refused to agree to new contracts that cut workers' pay and benefits.2 Buried in debt and estimating that the operations of the Balmer Mine would cost $40 million a year for the next five years, Westar sold both it and the Greenhill Mine to Teck Corp and Fording Coal Ltd, respectively. Union workers at Balmer signed a new five-year contract that October, and mine work began again.3

Since then, the market has continued to grow and change in the Elk Valley. Today, there are five mines in the region, all owned by Teck Resources, which has become the world's second largest seaborne exporter of steelmaking coal.4 The Elk Valley is currently home to the second largest, fifth largest, and sixth largest mines in BC, with the Elkview Mine earning $1.05 billion in revenue in 2012.

Yet despite the important role of the coal mining industry in Sparwood, the community today is multifaceted and diverse, with other economic drivers playing a large role in the economy of the town. Tourism in particular is an important part of life in Sparwood. Visitors can ski at the nearby ski hill, take tours of the coal mines, view the town's heritage murals, go golfing, or visit the famous Terex Titan truck.

Sparwood's history is one of change and growth, with deep roots in the coal mining industry and in the story of the small communities of Michel, Natal, and Middletown. It is a town made up of people and stories from other places, brought together by the desire to make a living and a home.

Endnotes

2. The Lure of Coal

1. "Virtual Museum: Mining Coal - Economics," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

2. Andrew Turgeon and Elizabeth Morse, "Coal," National Geographic, 2012, online.

3. Birth of the Coal Industry

1. "Virtual Museum: Natural History," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

4. The Dangers of Mining

1.Jillian Clark, "A Town Built on Coal Remembers its Fallen," RVWest, 2017, online.

2."Virtual Museum: Mining Coal - Costs," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

3. Liam Britten, "50 Years Ago Today, 15 Men Died in a BC Coal Mine Explosion, CBC News, 2017, online.

4. "Natal Mine Explosion Kills 15," Lethbridge Herald, Alberta, 1967, online.

5. "Virtual Museum: In Memorandum," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

5. Michel, Natal and Middletown

1. Arlene B Gaal, Memoirs of Michel-Natal, 1899-1971, 1971, 3.

2. Naomi Norton and Wayne Miller, The Forgotten Side of the Border, Plateau Press, 1998.

6. Life in Michel-Natal

1. Jillian Clark, "A Town Built on Coal Remembers its Fallen," RVWest, 2017, online.

7. The Coke Ovens

1. Gulhan Ozbayoglu, Comprehensive Energy Systems, Elsevier, 2018.

2. "Virtual Museum: Mining Coal - Economics," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

3. "Coke Oven Emissions," National Cancer Institute, 2019, online.

8. Pollution in Michel-Natal

1. Tom Langford, "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78," BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016, 33.

2. "Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in Canada," Government of Canada, 2018, online.

9. The Mid-20th Century

1. "Virtual Museum: Mining Coal - Economics," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

2. "Railways and the Coal Mining Industry," Atlas of Alberta Railways, University of Alberta Press, 2005, online.

3. Charlotte Helston and Andrew Farris, "Large Hydropower," Energy BC, 2016, online.

10. The End of Michel-Natal

1. Tom Langford, "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78," BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016, 32.

2. Tom Langford, 36.

3. Tom Langford, 38.

4. Tom Langford, 38.

11. Moving to Sparwood

1. Tom Langford, "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78," BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016, 45.

2. "Virtual Museum: The Move to Sparwood," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

12. The Difficulties of Relocation

1. Tom Langford, "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78," BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016, 40.

2. Tom Langford, 40.

3. Tom Langford, 31.

4. Tom Langford, 42.

13. The New Town

1. Tom Langford, "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78," BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016, 32.

2. "Virtual Museum: The Move to Sparwood," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

3. "Sparwood Marks Passing of Loretta Montemurro," District of Sparwood, 2014, online.

15. Today's Sparwood

1. "Virtual Museum: The Move to Sparwood," Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019, online.

2. John Davies, "Westshore Facility Hit Hard By Bankruptcies at Mines," The Journal of Commerce, 1992, online.

3. John Davies.

4. "A Recent History of Mining," Fernie & Elk Valley Cultural Guide, Tourism Fernie Society, 2022, online.

Bibliography

"A Recent History of Mining." Fernie & Elk Valley Cultural Guide, Tourism Fernie Society, 2022. https://elkvalleyculture.com/stories/industrial-heritage-a-recent-history-of-mining.

Britten, Liam. "50 Years Ago Today, 15 Men Died in a BC Coal Mine Explosion. CBC News, 2017. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/balmer-north-explosion-1.4054012.

"Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in Canada." Government of Canada, 2018. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/datalab/copd-blog.html.

Clark, Jillian. "A Town Built on Coal Remembers its Fallen." RVWest, 2017. https://www.rvwest.com/article/sparwood/a_town_built_on_coal_remembers_its_fallen.

"Coke Oven Emissions." National Cancer Institute, 2019. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances/coke-oven.

Davies, John. "Westshore Facility Hit Hard By Bankruptcies at Mines." The Journal of Commerce, 1992. https://www.joc.com/westshore-facility-hit-hard-bankruptcies-mines_19921213.html.

Gaal, Arlene B. Memoirs of Michel-Natal, 1899-1971. 1971. 3.

Helston, Charlotte, and Andrew Farris. "Large Hydropower." Energy BC, 2016. http://www.energybc.ca/largehydro.html.

Langford, Tom. "View of Class and Environmental Justice Politics in The Demolition of Natal and Michel, 1964-78." BC Studies, no 189, Spring 2016. 33.

"Natal Mine Explosion Kills 15." Lethbridge Herald, Alberta, 1967. http://www.gendisasters.com/british-columbia/12387/natal-bc-coal-mine-explosion-apr-1967.

Norton, Naomi, and Wayne Miller. The Forgotten Side of the Border. Plateau Press, 1998.

Ozbayoglu, Gulhan. Comprehensive Energy Systems, Elsevier, 2018.

Turgeon, Andrew, and Elizabeth Morse. "Coal." National Geographic, 2012. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/coal/.

"Railways and the Coal Mining Industry." Atlas of Alberta Railways, University of Alberta Press, 2005. https://railways.library.ualberta.ca/Chapters-1-3/.

"Sparwood Marks Passing of Loretta Montemurro." District of Sparwood, 2014. https://www.e-know.ca/news/sparwood-marks-passing-loretta-montemurro/.

"Virtual Museum." Sparwood Museum, District of Sparwood, 2019. https://sparwood.ca/parks-recreation-culture/arts-culture-heritage/#gsc.tab=0.