Walking Tour

Manotick

Dickinson Square - The Heart of a Village

By Lindy Marks

This project is a partnership with the Rideau Township Historical Society & Watson's Mill Manotick Inc.

1. Geology

This large boulder is better known as a glacial erratic—a boulder scattered at random in the countryside. Several smaller erratics are nestled next to the western flank of the larger one. The large erratic is slightly rounded and grey in colour with parts of its surface smooth and somewhat polished. Rub your hand over the surface and locate some of these smooth areas.

* * *

Erratics are boulders scattered at random about the countryside. This erratic is more appropriately known as a limestone erratic or a limestone glacial erratic as it is composed of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) with some fine clay mixed in. It is interesting to explore how limestone is formed and how this limestone boulder became an erratic, developed its round shape, and became so smooth in places.

This limestone glacial erratic started its journey some 480 million years ago in a marine or ocean basin where calcium carbonate was precipitated from the sea water by a chemical or organo-chemical process. Some fine clay was deposited with the calcium carbonate. This calcium carbonate was covered by other sediments and slowly sank into the crust of the earth, where elevated temperatures and pressure converted it into a consolidated rock known as limestone. Later, through uplift and erosion, the limestone became exposed on the surface of the earth.

At one time, approximately two-thirds of North America was covered by an ice sheet known as the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached its maximum extent 20,000 years ago. This ice sheet, the largest in the world, was up to three kilometres thick in some areas. The south-moving sheet broke off a block of limestone and carried it within or at the bottom of the ice. As it was moved, the limestone ground against other rocks and ice, and in the process, its rough edges were rounded, with local areas smoothed and polished. It eventually got incorporated into the ice mass and moved along with it.

At this point in its journey, the erratic could have followed one of several paths. One possibility is that when the ice mass started to recede and break up, large blocks of ice formed ice bergs, one of which carried the rounded boulder. When the iceberg melted, the boulder sank to the earth's surface. These erratics are known as drop stones. Another option is that the boulder was transported by the glacier and then left behind when it melted.

The remains of living marine organisms are commonly referred to as fossils. Most limestone contains visible fossils, but none are visible in this limestone erratic. Limestone is used in road and railway construction, concrete, roofing granules, cement plants, blast furnaces, glass factories, and fertilizers, and is also used as building stone. To witness the latter, examine the rocks in the wall of the Mill. They are approximately the same age and composition as the limestone erratic. Local history suggests that the rocks used in the construction of the Mill were quarried locally. They were cut and shaped by stone masons who creatively arranged and mortared them to form the walls of the Mill. They have been in place for over 160 years.1

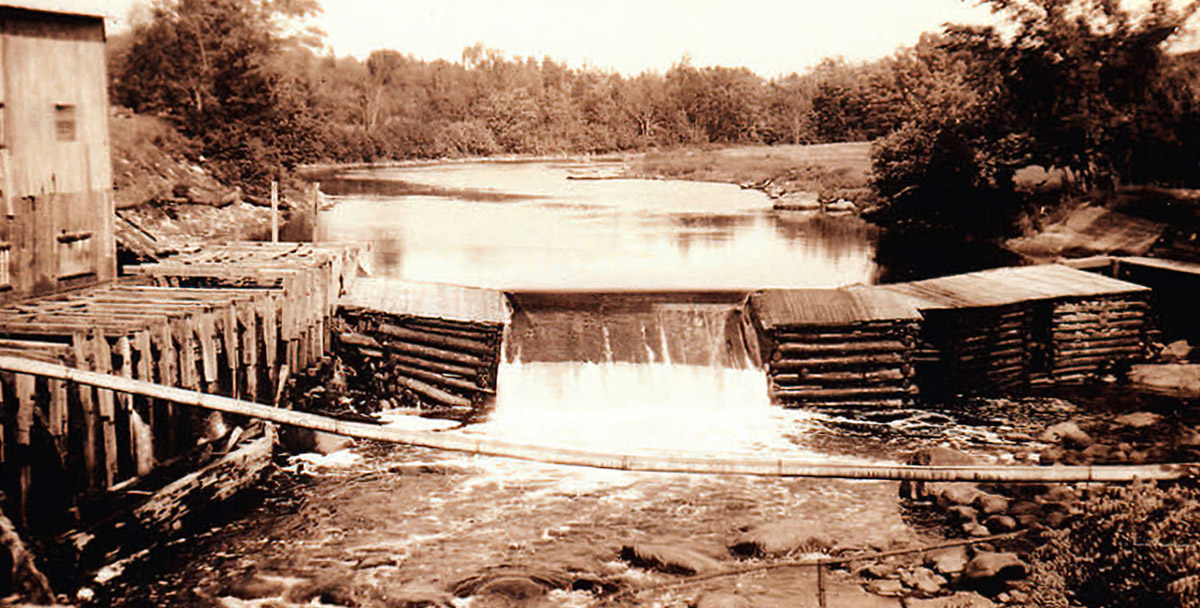

2. The Weir and First Sawmill

This photograph shows a weir that predated the current bulkhead dam and was located just upstream from the current dam location. On the left side of the photo is a building that is believed to be an early sawmill.

* * *

A weir is a low dam built across a river to control and often increase the upstream water levels. This might be done for a number of reasons, like running a water wheel or making a section of the river easier for larger boats to navigate.1 Another type of weir is a waste weir, which is used on a canal to remove excess water from storms or the emptying of locks. Excess water can lead to the erosion of the banks of a canal, which can in turn lead to washouts and flooding.

Canals and rivers were the only ways to move large amounts of goods cheaply during the early industrial revolution; there were no trains yet and the roads that did exist were uneven and often in poor condition. When the ground thawed in the spring, for example, roads turned into mud slicks that were dangerous, if not impossible, for horses to travel.

The St. Lawrence River route was the primary shipping route prior to 1815, but it had upstream rapids which made navigation difficult for larger vessels. Steamboats regularly ran the rapids when going downstream but could use the Ottawa River/Rideau Canal route to avoid the rapids when travelling upstream. In addition, it follows the international border and was used heavily by American shipping companies. In the event of war it could easily be blockaded by the United States, severing the maritime link between Upper and Lower Canada. During the War of 1812, American troops crossed the St. Lawrence into Canadian territory a number of times.

Shortly after the war, it was discovered that the Americans had made plans to cut off access to the St. Lawrence, which would have devastated business and military operations on the Canadian side of the border. These plans highlighted the vulnerability of the river and the need to have a second, more secure route.

This second route would link Kingston and Montreal, like the St. Lawrence, but it would instead follow the Ottawa River from Montréal to the mouth of the Rideau River at present-day Ottawa and then continue south along the Rideau and Cataraqui Rivers to Lake Ontario at Kingston. In other words, it would follow an all-Canadian route, which would protect it from American interference.

Some parts of this new route were only navigable by canoe, so a series of locks had to be built between Ottawa and Kingston. Most of the work was done by hand, though some was done with the help of horses and oxen. Most of the labourers were Irish immigrants and French Canadians. This was the creation of the Rideau Canal, which opened in 1832.

3. Bulkhead Dam

Following the washing out of a weir located at the north end of Long Island in 1858, the bulkhead control dam was built. This dam was central to the development of Manotick and was expanded in the 1870s.

* * *

The history of the Rideau Canal and the villages that grew up beside it is a common story in Canada's early industrial revolution: resourceful pioneers harnessed new technologies to create a thriving community.

The transformation was stark. In 1827, decades before the Dickinsons arrived, Long Island, the land area at the far end of the dam was described thusly: “A piece of rougher wilderness could with difficulty be found in Canada.”1 By the time the canal was finished in 1832, a small settlement known as Long Island had formed adjacent to the locks of the same name at the north end of the island. Long Island consisted of just 11 buildings.2

Access to hydropower shaped settlement patterns in this era of Canadian history, and the bulkhead dam seen here, along with the mills built by Dickinson and Currier, ultimately spelled the end of the settlement at Long Island, as people were now drawn to the mill site instead. When the dam was built in 1858, Moss Kent Dickinson and Joseph Currier leased the water rights from the federal government and acquired about 30 acres of land on both sides of the channel.3 This was the beginning of Manotick.

4. The Grist Mill

1920

This photo shows the limestone grist mill, built in 1859, which now houses the Watson's Mill Museum. Still powered by water turbines just as it was when it was built, the mill remains partly operational today.

* * *

Grist mills were often the heart of the community in nineteenth-century Canada. They were where farmers, merchants, and townspeople interacted with each other. Community ordinances, like marriage notices, were often posted on the doors of the village mill.2 Operating the mill required cooperation between the mill's owners, the farmers, and the community; Dickinson and Currier, for example, provided a scow for farmers to bring their grain to the mill, which doubled up as a ferry until the late 1860s.3

The mill was built with state-of-the-art machinery manufactured by Ottawa's Victoria Foundry, of which Joseph Currier was a part owner.

Four sets of grinding stones quarried in France produced up to 100 barrels of flour each day.4 Farmers could have their grain ground at the mill either for cash or for payment in kind, and the mill also ground provender, or animal feed. In 1870, 50,000 bushels of grain were processed. A year later, production had increased by half, to 75,000 bushels.5

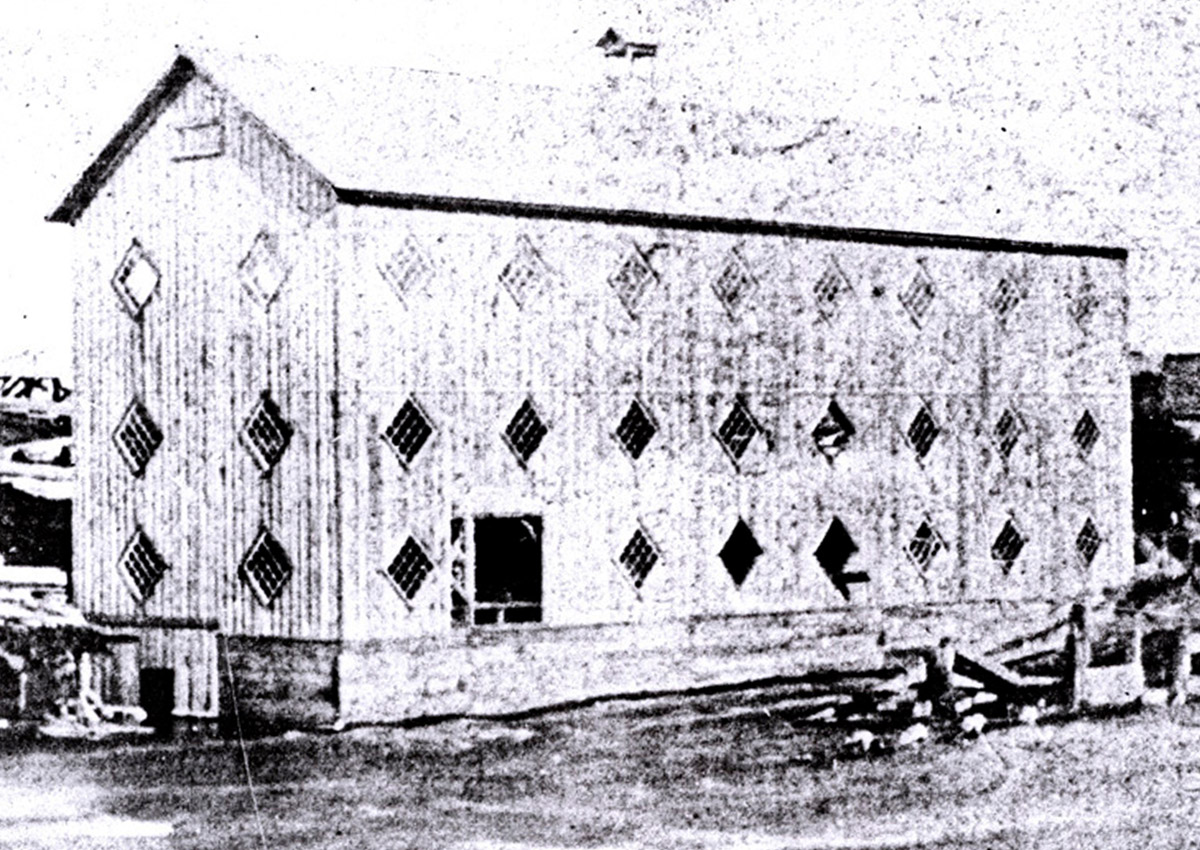

5. The Carding Mill

Here, we see a model of the carding mill that stood on this spot from 1861. The model is today found in the Watson's Mill Museum.

* * *

Carding prepares fibres like raw wool for being made into felt or yarn. In this process individual fibres are oriented lengthwise by the carding process forming a loose orderly roll of parallel wool fibres called sliver or roving. The roving was spun elsewhere into yarn which was then woven into finished textiles.

This process was traditionally done by hand, but in the nineteenth century, water-powered carding mills like this one became popular because they sped up the process significantly—some mills could card as much wool in one hour as a hand carder would produce in one week! This is a clear example of the transformational effect of the industrial revolution. The ability for a machine to speed up work by this much changed everything.

The Dickinson carding mill offered both custom and commercial carding. The machinery for this mill was built as early as 1860, and the building that housed it was built in 1861. At this time, the mill also had equipment to dye cloth.

The building was expanded sometime between 1861 and 1871 to make space for the manufacturing of cloth. It is believed that the carding mill burned down at some unknown date—the last mention of it in official documents is on a map of Manotick dated 1879.1

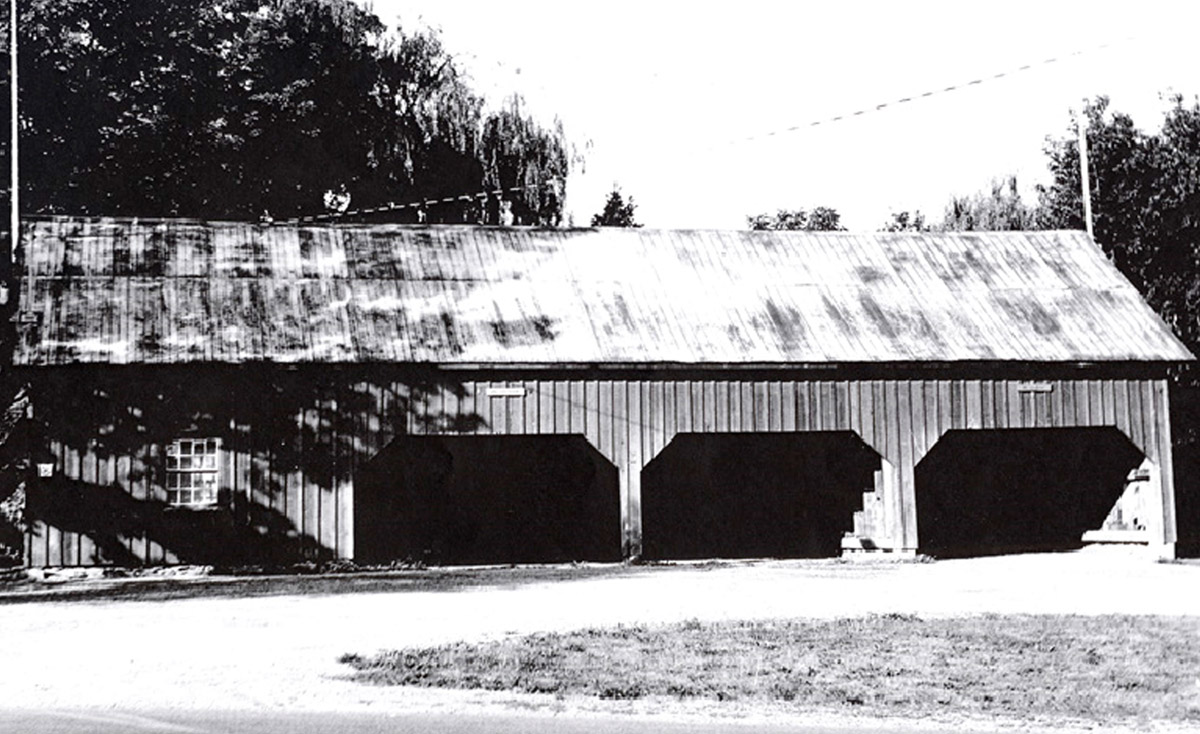

6. The Carriage Shed

Here, we see one of the two carriage sheds that originally stood on this spot. These carriage sheds are where the Dickinsons would have stabled their driving horses, light carriages, and sleighs which were used extensively for both business and personal matters.

* * *

While we might assume that the introduction of industrialization reduced the amount that humans relied on horsepower, the opposite is true.

Throughout the nineteenth century, horses were an important intermediary form of power between human muscle and steam power. Firemen, for example, pulled fire engines until the introduction of steam-powered pumps made them too heavy and a team of horses was needed instead.1

The demand for horsepower was so great that the global population of horses is estimated to have peaked between 1910 and 1920 at approximately 110 million horses. This was double the number of horses that existed just a century earlier and four times the number of horses that existed before the onset of industrialization! In Canada specifically, the population of horses sometimes grew faster than the population of humans. This was true of Ottawa and the surrounding area.2

The importance of horses was felt keenly during an outbreak of equine influenza in the 1870s. Beginning in the Toronto area, the disease followed transportation routes across Canada. It disabled 80-90% of working horses for a week or longer, while 1-2% of the horse population died from the illness. Entire cities ground to a halt when horses were too ill to work. Deliveries suddenly needed to be made by hand, and there are some reports that wagons had to be pulled by teams of men. Horses in cleaner, airier, and more spacious lodgings weathered the illness better than their counterparts in underground stables in larger cities, which may have helped the Dickinson horses kept in these carriage sheds.3

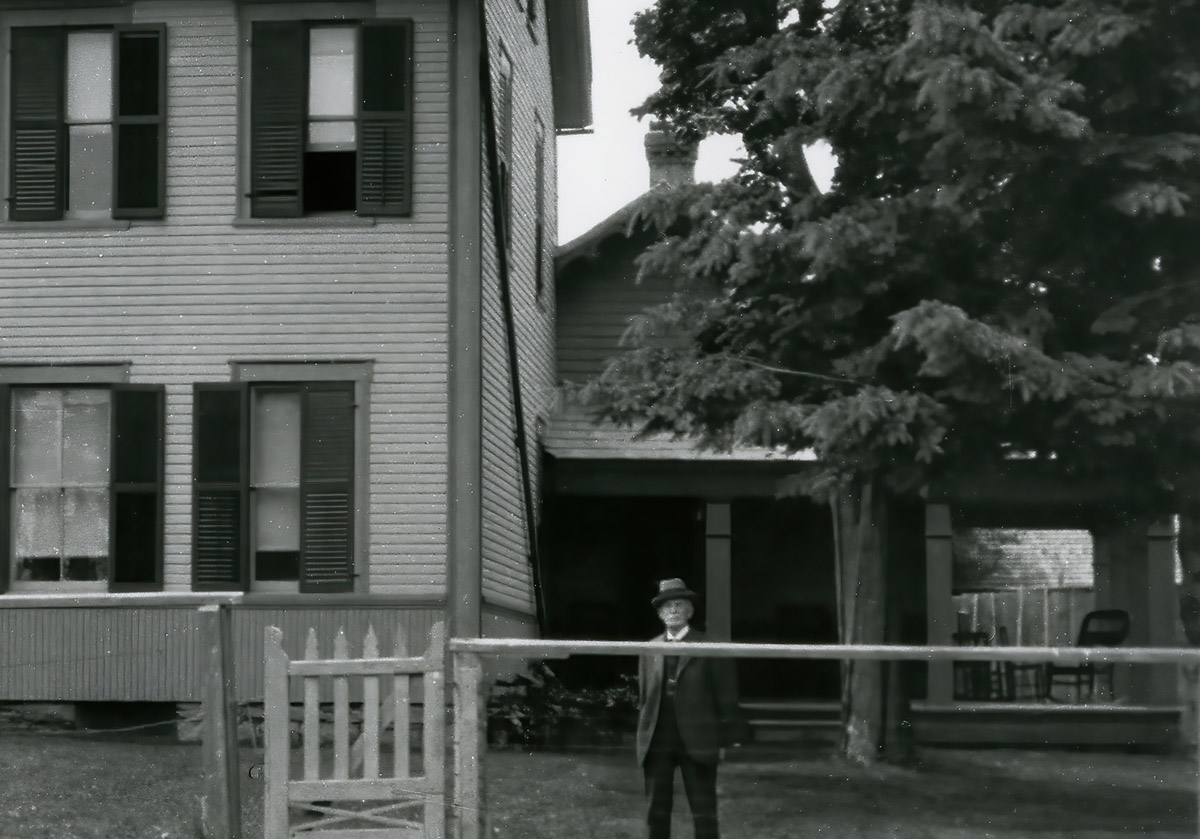

7. Willie Dickinson

Library and Archives Canada LAC3317751

In this photo, Moss Kent Dickinson's son William (Willie) is standing in front of the Currier cottage, named after Joseph Currier, business partner to Moss Kent Dickinson. He was also a lumber baron and Ottawa's first Member of Parliament. In this role, Currier advocated for Ottawa to become the national capital. When Dickinson House was constructed in 1867, it was attached at the northwest rear corner to what was known as the Currier cottage.

* * *

Willie was heavily involved in running the family businesses: he managed the financial ledgers, co-owned a farm on Long Island, and may have run the grist mill, if an 1886 newspaper is to be believed. After George was elected to the House of Commons in 1888, Willie became the Manotick postmaster and remained in this role until 1897. He also remained involved in the family businesses, becoming a co-owner of the grist mill with his siblings in the 1920s.

Perhaps in connection with his business life, Willie was a member of the Independent Order of Foresters (IOF), which was originally a British friendly society. Before modern insurance or pension programs, friendly societies were mutual aid organizations made up of individuals who banded together to provide these types of financial and social services to their members. These groups usually formed around religious, political, or business affiliations.

While not a lot has been written about Willie, we do know that he was not simply a quiet, business-minded man. In 1886, the IOF held a special banquet during which the members prepared a banquet for the women in their lives. After the banquet, one of Willie's sisters formed a chorus and began singing songs. The big hit of the night, however, was when Willie sang his own version of 'Miss Fogarty's Christmas Cake.' Willie altered some of the words to the song and called his version 'The Foresters Christmas Cake.'1

Like his siblings, Willie never married. He was, however, engaged for a time to a woman from Richmond. Their engagement was broken off just weeks before the wedding when his fiancée eloped with one of Willie's friends—the one who was meant to be the best man at their wedding. Willie lived out the rest of his life in Dickinson House, dying at home in March of 1930. He was 76 years old.

8. The Dickinson House

Library and Archives Canada LAC3317751

A wider view of the previous image, this photo shows the way Currier cottage was integrated into the design of Dickinson House when it was built in 1867. The man on the left is Moss Kent Dickinson's oldest son, George.

A two-and-a-half storey Classical Revival building, Dickinson house draws upon New England architecture from the Georgian period. The building was originally used as the mill offices, a general store, and a post office. Even after the Dickinson family moved into the house in 1870, it remained a central community hub.

* * *

Many meetings, including those of both the Manotick Women's Institute (WI) and the Ladies' Guild of St. James Anglican Church were held here. In the early 1900s, the Ontario Department of Agriculture sent representatives to visit villages in the interest of establishing branches of the WI. An organizing meeting of this nature was held in Manotick on January 6, 1909, and in February of that year, the first Manotick Branch meeting took place. Several fundraising socials took place on the lawn of Dickinson House.

The house was also important for its gardens. Gardens were critical in providing fresh, healthy food for families and communities during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They were so important, in fact, that Bessie Dickinson, as part of the Programme Committee of the Manotick Women's Institute, organized educational presentations on gardening, health, and food preparation and preservation.

Many of these home gardens also grew herbs, which have been prized for centuries for their medicinal, culinary, and household uses.

Nineteenth-century herb gardens were built as “door-yard” gardens—gardens that were located just past the kitchen door. These gardens were planted both with seeds imported from Europe, and domestic species whose properties and uses settlers learned from the Indigenous peoples. Indigenous people across Canada use more than 1,000 different plants and settlers have benefited greatly from the knowledge these communities generously shared with them.

The Heritage Herb Garden that is located behind Dickinson House today reflects these two sources of plants and contains herbs that were commonly found in nineteenth-century Ontario gardens. The fresh crushed leaves of North American bergamot, for example, were used to calm irritation caused by insect bites. Bergamot tea was used to soothe stomach aches and the leaves could be boiled to treat acne.

Household uses for herbs included marigold as colouring for cheese or a hair rinse for brunettes and soapwort which produces a mild soap or shampoo when mixed with water.

9. The Dickinson Complex

Library and Archives Canada LAC200356

1867

Taken circa 1867, this photograph shows what the full Dickinson milling complex looked like around the time of Confederation. All of these mills provided services and employment to the residents of Manotick and the surrounding area, making the complex central to the village economy.

* * *

Over his lifetime, Moss Kent Dickinson was heavily involved in local and federal politics. He was the mayor of Ottawa and a Member of Parliament. First elected as mayor in 1863, Dickinson became Ottawa's tenth mayor and eventually served three one-year terms from 1864-1866.

During his tenure as mayor, Dickinson negotiated an agreement for the Grand Trunk Railway to take over the nearly bankrupt Bytown and Prescott Railway. He petitioned for Majors Hill to be used as a public park, and he was the mayor in office when Ottawa established a horse-drawn tram car service in the city.

He did not, however, address the lack of running water, the bad roads, or any of the other infrastructure problems facing the city.1 He chose not to seek re-election in 1867. After moving to Manotick in 1870, Dickinson remained involved in municipal politics. He made numerous presentations to the North Gower municipal council and was appointed to chair council meetings on various occasions.

Dickinson became directly involved in federal politics when he was nominated as the Conservative candidate for Russell in the 1882 election. He ran in Russell because the race for the nomination in Carleton County was quite crowded.

In Russell, there were four other nominees, but Dickinson won the nomination. He went on to defeat the Liberal candidate in the election.

Dickinson was not very active in the House of Commons, making his first speech three years into his term. In this speech, he congratulated the Minister of Finance for his “masterly and exhaustive Budget Speech” before reiterating his support of the Conservative government's fiscal policies by claiming that “it is not difficult for any unprejudiced, impartial mind, to establish that the policy of the present Government is eminently in the best interests of our country.” Dickinson was particularly pleased that tax rates had decreased by 10 cents per person under the Conservatives.2

He sat on several committees but was not involved in any of them in a major way. He seemed to enjoy his responsibilities to his constituents, however; he often attended picnics and agricultural fairs. He worked hard to bring better mail service to the county.3

Dickinson chose not to run again in 1887, refusing a nomination. He did, however, agree to run again in the 1891 election. He lost this election to the Liberal candidate, and this marked the end of his career in federal politics.

10. The Second Sawmill

Library and Archives Canada LAC_a191438-v6

ca. 1875

Note that the photos for this spot were taken further along in A.Y. Jackson Park.

On the left of this photograph, across from the grist mill, is the second sawmill on this site. It was built in the 1870s to replace the original sawmill.

11. The Iron Bridge

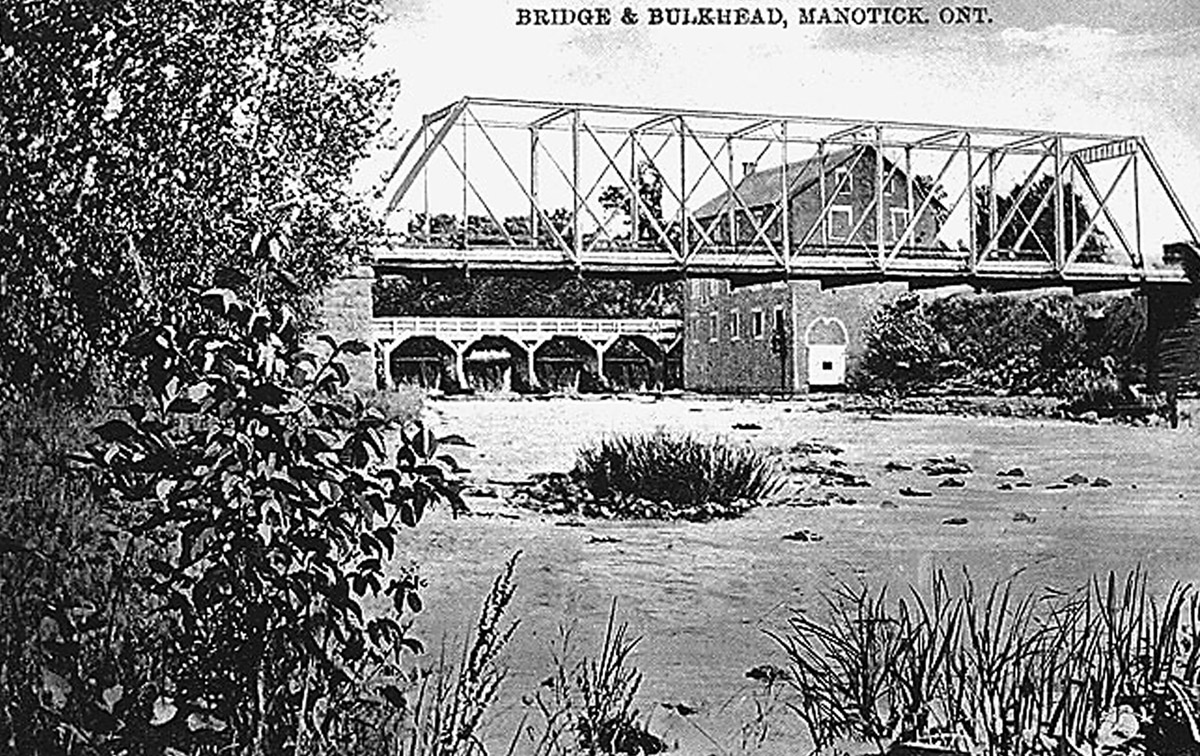

This photograph shows the iron bridge and, visible in the background, the bulkhead dam and the grist mill. The bridge was finished in 1885 and aligned with present day Clapp Lane. The supporting foundations of the bridge are still visible from the War Memorial, and on the opposite side of the channel in A.Y. Jackson Park.

* * *

At first, barges had to be used to transport goods and people across the east and west channels of the river. This was very inconvenient and impeded the growth of Manotick, especially because three levels of government had to be involved due to the existence of the Rideau Canal.

The introduction of bridges across the Rideau was a significant development that began with a swing bridge completed in 1867 spanning the eastern channel of the river that complemented a wooden bridge built across the western channel. A swing bridge is a bridge that swings open to allow boats to pass through. Joseph Currier was heavily involved in the construction of this bridge through his role as a Member of the Provincial Parliament. He was part of the group discussing the need to build a bridge over the Rideau Canal using public funds. A major part of the debate was where the bridge should go. Two locations were considered, but Currier “insisted that the bridge be built in Manotick or not at all.”1

This decision shaped history. A village named Long Island had been established at the north end of Long Island in the 1830s, and by the time Manotick was settled in 1860, the village was thriving. As Manotick began to develop, however, the growth of Long Island slowed; in comparison to the new village, Long Island had little to offer to the working class in terms of steady work. Long Island was dealt another blow when its citizens lost their chance to have the new swing bridge built at the site of their village rather than at Manotick. People left Long Island for Manotick, and the village's churches and businesses closed down. Hardly anything is left of the Long Island settlement today. The bridge directly benefited Manotick by providing easier access to the railway at Manotick station, which was critical for moving mail, freight, and passengers.2

George Dickinson, in his capacity as Carleton County councillor, was involved in the construction of the iron bridge, the other major bridge in Manotick. In 1885, the county council began to consider building a replacement bridge over the western channel of the Rideau River. A committee determined that the old bridge, which had been in place for 14 years, was unsafe. The committee also recommended that the council investigate the cost of replacing the wooden bridge with an iron one. George was part of the three-member committee that oversaw the construction of the new bridge, which was completed and opened to the public in December of 1885.

12. Clapp Barns & Express Service

Wearing a newsboy cap in this photo, Johnston Clapp turns towards the camera in the middle of harnessing two horses to a wagon. Clapp operated the horse-drawn express wagon service that met the train at Manotick Station.

* * *

As previously discussed, horses were central to transportation in this period. Horses drew wagons, carriages, and recreational vehicles like sleighs. Ottawa during this time even constructed a horse-operated tram system that ran throughout the city.

In the 1850s and 1860s, transportation by rail was beginning to replace transportation by steamboats and barges, which led to investments in railways. Dickinson's brother Walt and his brother-in-law Alpheus Jones were two of the founding investors of the Bytown Prescott Railway.

The Bytown and Prescott Railway had unfortunately bypassed Manotick proper. Manotick station was at least three miles away from the village. It was too far for passengers or delivery people to easily walk, especially when burdened with luggage or heavy parcels. Products made in the Dickinson mills were also shipped by rail. This created a need for transportation between the village and the station, and a horse-drawn express wagon service was set up for this purpose.

In 1892 there were discussions about building a railway from Kingston through Smiths Falls to Ottawa. Dickinson knew that having this railway pass directly through Manotick would increase property values, business opportunities, and transportation efficiency in the village.1

Dickinson became a staunch advocate of this plan. For it to work, however, it would have to be supported by Marlborough and North Gower through either tax subsidies or direct investment in the railway company itself. Meetings of ratepayers were held throughout the counties, and the community of Manotick was particularly enthusiastic. The results of these meetings are not known, but a rail line through Manotick was never built. Being continually bypassed by the railway took a financial toll on Manotick and led to the village's gradual decline for a number of years.2

13. Second Sawmill from West

Library and Archives Canada LAC_c000724

This photograph is of the second sawmill from a westward view. The lengthening of the bulkhead dam in 1870 forced Dickinson to replace the original sawmill with this larger one. Unfortunately, it burned down in 1887.

* * *

George Dickinson, who was born in 1848, was an outgoing and engaging man. He was the postmaster of Manotick from 1869 until 1888, when his brother Willie took over the role. He had an active political life at both the local and federal level.

In 1877, George was elected deputy reeve of the Township of North Gower. George was one of five men nominated for the position. Three of the others declined to run, so the race was between George and John O'Callahagn, a man from a prominent Irish family who lived in the Kars area. George won the election by 26 votes.

Moss Dickinson had been calling for a gravel road to be built from North Gower to Manotick, and this was George's first project as deputy reeve. At his second council meeting, George introduced Bylaw 114, which stipulated that the gravel road Moss desired would be built using the municipal fund set aside for road construction. The bylaw passed and was George's first victory on council. This victory, however, was short lived; at George's third council meeting, just three weeks later, Bylaw 115 was introduced and passed—it rescinded Bylaw 114!

George was acclaimed to the position of deputy reeve in 1878 but did not run for re-election in 1879. Georgina and William Tupper speculate that this was because he was needed at home, managing the Dickinson family businesses during a time of financial crisis.1

When the Carleton County federal seat became vacant shortly after the 1887 election, George sought the Conservative nomination. After four rounds of voting, George won the nomination and was endorsed by his brother, William. He went on to win the by-election.

His interest in the position, however, seemed minor at best. He never made a major speech in the House and concerned himself primarily with passing a private member's bill to regulate fraternal and benevolent societies. This bill ultimately failed while George was trying to increase the value of a timber lease he held in Saskatchewan.2

George was embroiled in a minor scandal when conflict of interest charges were levelled against him for voting for a bill that would give a land grant to the Manitoba Canal and Railway Company—the same company in which his father, Moss, had a financial interest.3 After Parliament was dissolved in 1891, George ran for the seat again but lost to his opponent, William T. Hodgins.

This defeat ended George's political career, though he was later appointed a Justice of the Peace. He died of heart failure in Ottawa in 1930. Like his brother Willie, he never married.

14. The Bung Mill

The bung mill, pictured here, was built after the large sawmill, where the bungs were originally made, burned down in 1887. It was one of only two bung mills in Canada and continued to operate until 1904. Bungs are tapered wooden plugs that are used as stoppers or barrel plugs, while spiles are wooden taps used for drawing liquids out of barrels.

* * *

In 1875, a 20-foot addition was added to the sawmill to accommodate the making of bungs and spiles. It was known as the Canada Bung, Plug & Spile Factory, and advertisements named George Dickinson as the proprietor.

The bungs produced here were made from a variety of woods. Bass was the most popular, but they were also made from oak, spruce, and maple. Pine was the preferred wood for spiles, but here again there was a variety of woods used, including pine, oak, maple, and bass. Each product came in several sizes, ranging from 1.25 to 4.5 inches in diameter.

Customers could purchase individual bungs and spiles, but they were most commonly sold by the barrel. A barrel of bungs could hold up to 2,900 bungs. The bungs and spiles manufactured in the Dickinson complex were sold globally and even won awards in Scotland, throughout Asia, and in the Caribbean.1

In Scotland, the bungs were used primarily for whisky barrels. They were used for this purpose in Canada too—some of the clients of the bung mill were companies now known as Canada's oldest distilleries. These include H.R. Molson and Brothers, J.P. Wiser, and Hiram Walker & Sons.2

15. Bessie Dickinson

This photo shows a view of Dickinson Square after the Union Bank was built in 1902. The women are both wearing long, dark dresses with full length sleeves, and the woman to the right sports a large hat. These outfits are consistent with women's fashion in the first decade of the 20th century. The bank was built at a time when bank managers were expected to live above the bank for security purposes.

* * *

Bessie was an active and integral member of the Manotick community. She was one of the eleven women who founded the Ladies' Guild of St. James Anglican Church in 1893 and was elected secretary at the first meeting. In 1902, she became the Guild's vice-president, and from 1905-1916, she held the role of treasurer.

The main purpose of the Ladies' Guild was to fundraise for the upkeep and furnishing of St. James. The women put on concerts, bazaars, flower shows, church suppers, and lawn socials. Many of these lawn socials were held at Dickinson House, and they included games and music and the sale of lemonade, homemade treats, and embroidery. It was Bessie who suggested that the Guild sell ice cream at the Long Island Locks during the summer of 1915. By July, she reported that this activity had become “a flourishing business.”2

Bessie was also a founding member of another women's organization at St. James—the Women's Auxiliary (WA), which started in 1904. The WA was another fundraising organization, but in this case the money supported Anglican Church missions that aimed to convert people to Christianity. These missions took place globally and in Indigenous communities across Canada.

Bessie was well-known and well-liked in Manotick. When she left the village to go to Ottawa for breast cancer treatment in 1930, the Ladies' Guild of St. James sent flowers to Bessie, and members took turns writing to her every week. This was done for the next year and a half.

Bessie died in Ottawa on April 25, 1933. She was 71 years old and the last surviving member of the Dickinson family.

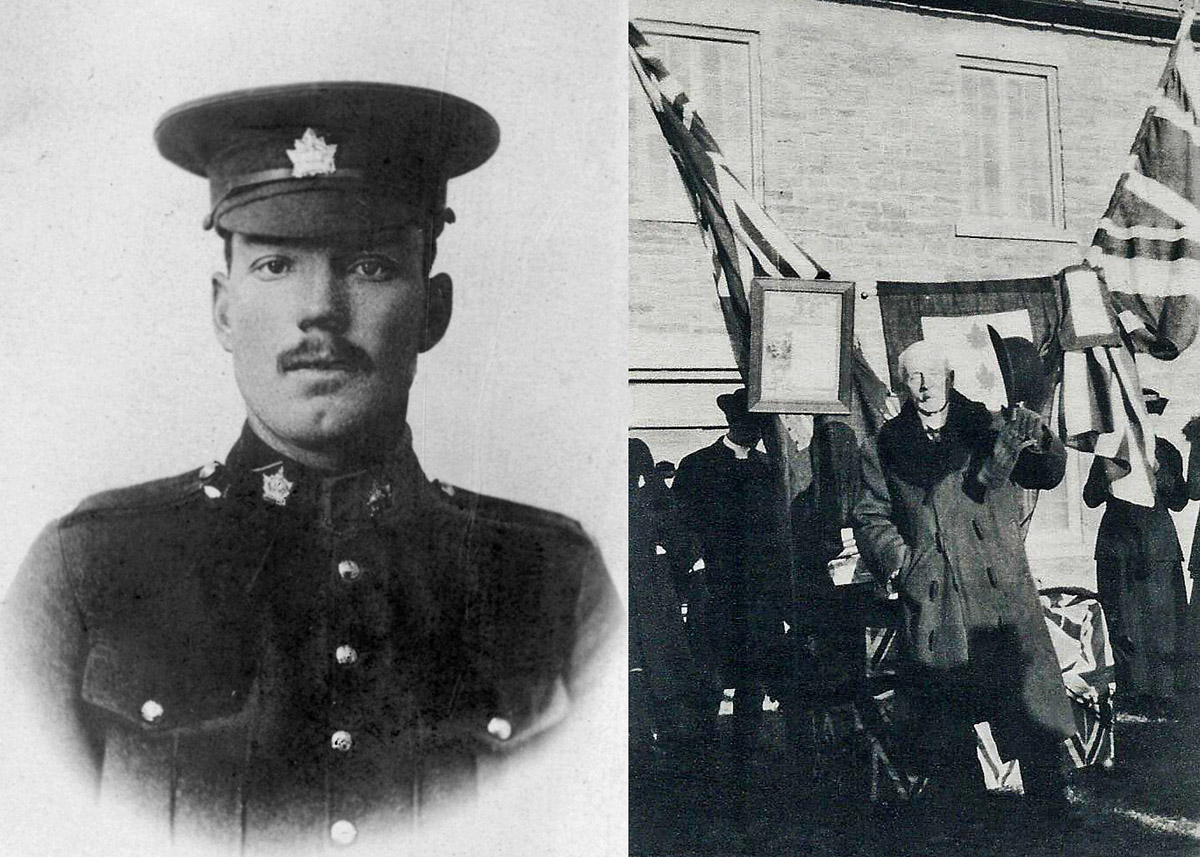

16. Memorial Park

The man in the photo on the left is Hugh Stamp, who enlisted as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force on July 17, 1915. He was one of many local residents who served during the First World War. He was killed in action on August 18, 1917. The photo on the right shows George Dickinson in front of the grist mill on Armistice Day.

* * *

The two Dickinson sisters, Charlotte and Bessie, were close and had many friends in common. They were an integral part of the Manotick community, and both joined the Manotick Women's Institute (WI). The WI records are the only source of information available giving any insight into Charlotte Dickinson's character, perhaps reflecting that since she was ten years older than Bessie and the eldest female member of the Dickinson family, her life was more focused on home and family duties.

At the outbreak of the First World War, contributions to the war effort became the major focus of the WI, beginning when Bessie Dickinson moved that the group contribute $20.00 to the Red Cross Fund in August, 1914. It was after this time that the group, began to hold hour-long meetings for the purpose of sewing and knitting for the Red Cross

The WI continued to support soldiers and the Red Cross throughout the war in a variety of ways. The women made jam, knit socks, and sewed nightshirts. For Christmas in 1915, they filled 50 stockings for soldiers overseas. Two years later, they held a quilting bee to support Belgian relief. Charlotte called for 'silver money' to be collected at the end of each meeting, a practice which “contributed significantly to the collection of funds for the Red Cross by the Manotick WI.”1 The 'silver money' Charlotte was referring to may have been Canada's first domestically produced coin: a silver fifty-cent coin with the profile of Edward VII on it. The WI continued to support soldiers after the war ended. They arranged to greet soldiers returning home to Manotick, and when the Soldiers' Settlement Board appealed for help for soldiers who had settled in the north and were suffering a lack of crops, the WI carried a motion to make clothing for their children. Bessie made baby dresses and Charlotte made booties. The contributions of the Manotick WI to the war effort should not be forgotten.

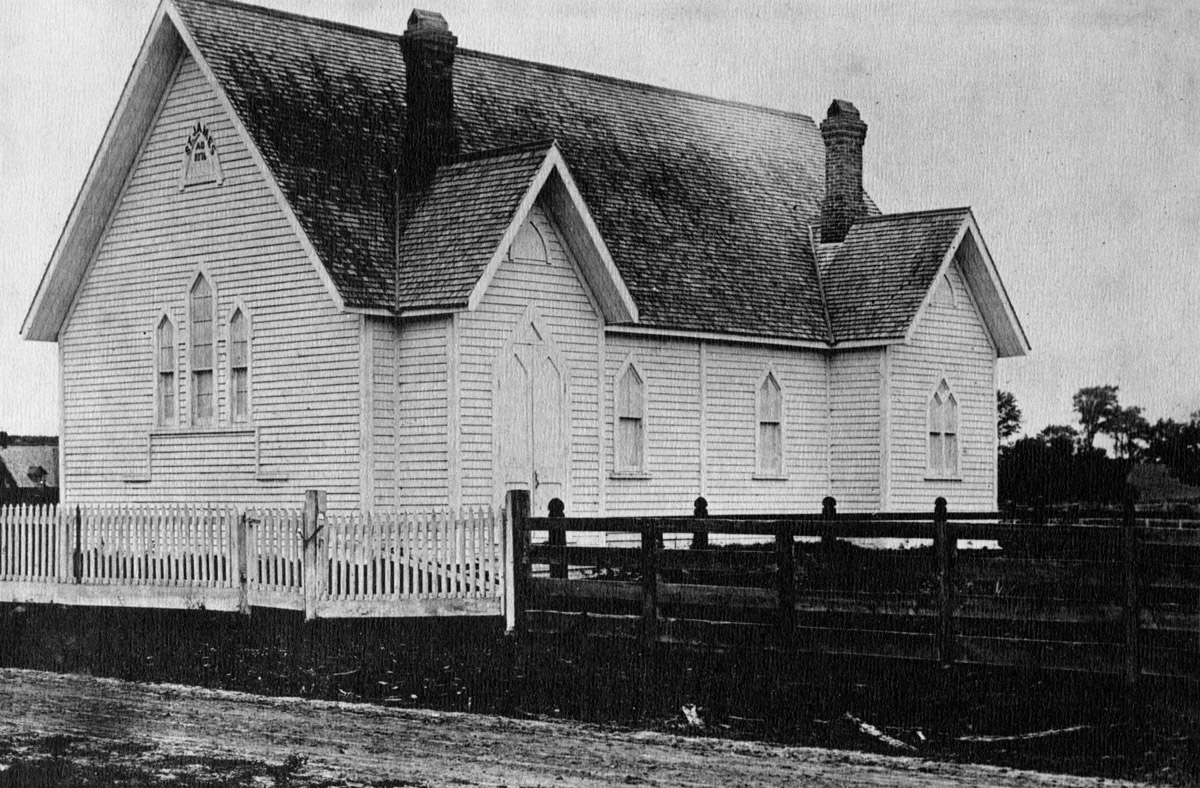

17. St. James Anglican Church

Older than the current Presbyterian Church in Dickinson Square, St. James Anglican Church was built on land donated by Moss Kent Dickinson, who also sat on the church's building committee. The church that stands here today is a 1985 expansion of the original church, which was built in 1876. The church has retained its original stained glass windows, plaques, and furnishings.

* * *

The close cooperation of people from different Protestant congregations is notable in Manotick in this period. In 1873, Father O'Loughlin was the Anglican priest of North Gower parish. He conducted his services in the First Line schoolhouse about four miles north of present-day Kars. Just a few years later Moss Dickinson, himself a Presbyterian, donated land for the construction of an Anglican Church for O'Loughlin's congregation. Moss even served on the church's building committee. St James Church was consecrated in 1876.

These differing faiths could be practised within families, and were apparently fluid. Charlotte was a staunch Presbyterian, while Bessie was committed to Anglicanism.

The same flexibility in religious affiliation can be seen in the lives of the Dickinson sons George and Willie.

Willie was listed as Presbyterian in the 1881 census but considered an Anglican by 1892. Manotick Presbyterian Church Communion Rolls, however, included Willie again in 1905.

There is a similar story for George. He was listed as a Presbyterian in the 1881 census, but shortly before that, like his father and brother, had been contributing to the salary of the Anglican rector, though his last contribution was made the same year the census considered him a Presbyterian. George made it onto the Presbyterian Church rolls in 1907, but when he died in 1930, he was buried in Beechwood Cemetery with Anglican ministers officiating.

When Bessie died in 1933, she left bequests to the Manotick Women's Institute, the church fund at St. James, and the Ladies' Guild. The Ladies' Guild used the $100.00 that Bessie had left them to purchase a church altar, inscribed with the following words: 'To the Glory of God, and in loving memory of Elizabeth Dickinson.' The altar still stands in the church today.6

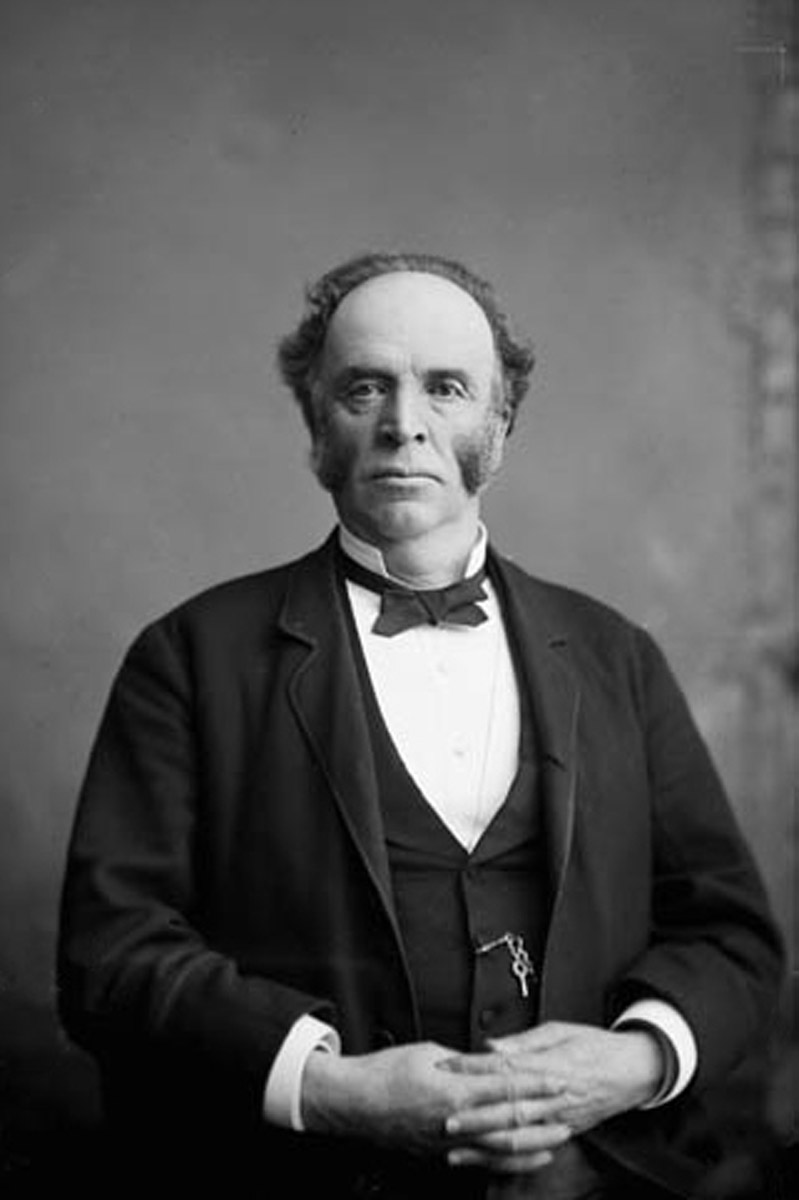

18. Dickinson Plaque

Library & Archives Canada 3419966

This plaque was erected by the Rideau Township Historical Society to honour the memory of Moss Kent Dickinson, founder of Manotick.

In this portrait, Moss Kent Dickinson sits in a dark suit with a waist-coat and a bow-tie, his hands clasped in front of him. He appears to be a broad-shouldered, slightly heavy-set man with a Roman nose, wide mouth, and prominent mutton chops. The plaque on this spot commemorates Dickinson's role in the founding of Manotick. As the last act of the Dickinson family, Bessie Dickinson, the last surviving member, conveyed this plot of land to the village for $1.88 just two years before her death in Ottawa.1

* * *

The 1870s was a time of economic depression in Canada, and this devastated the Dickinson enterprises. From 1887-1880 the amount of grain ground in the grist mill declined. Moss took out a loan in 1876, but by 1887 was struggling to make payments on it. He renegotiated the loan so that he could sell a number of lots in Manotick and reduce the amount he owed.

A meeting of Dickinson's creditors was held in February of 1879. The Union Bank took possession of the sawmills, the grist mill, and Dickinson House along with its yard and gardens. The bank also decided, however, to lease all of these properties to George Dickinson for $100.00 per month.1

The financial challenges facing the family continued to grow. In 1887, the grist mill was only producing 31,000 bushels of flour.2 That same year, the sawmill burned down, which dealt a serious blow to the family's income. George was unable to make any lease payments to Union Bank that year.

After some timber dealings in the first years of the twentieth century went badly, the company that owned the Dickinson's Manotick properties decided to cut their losses and sell the properties for a fraction of what they were worth. George was able to purchase the land, Dickinson House, and the mill for $5,500.3

Charlotte, George, and William passed away within 17 months of each other, from June 1929 to November 1930. Bessie left Manotick to receive breast cancer treatment in Ottawa in late 1930. In 1931, she agreed to sell Dickinson House and land to Alexander Spratt, the new mill owner. Spratt later sold the home to the Watson family in the 1940s. The Watson family gave their name to present-day Watson's Mill.

The departure of Bessie from the village in late 1930 marked the end of an era in Manotick. Over the previous 60 years, the Dickinson family had built and nurtured the community as it grew from a sparsely populated mill site to a bustling village. All three of the Dickinson men were active in local or federal politics, and the whole family actively participated in global events such as providing support for local soldiers during the First World War. Their legacy lives on in Dickinson Square, especially through Dickinson House and Watson's Mill, which have been turned into vibrant museums that pay homage to an earlier time and Manotick's founding family.

Endnotes

1. Geology

1. Special thanks to geologist Dr. William Tupper for writing this tour stop.

2. The Weir and First Sawmill

1. Ron Wilson, “The Rideau Canal at Manotick, Early Days,” Rideau Township Historical Society Newsletter, May, 2009, online.

3. Bulkhead Dam

1. James MacTaggart, qtd. in Catherine Carroll and Barbara Humphreys, A History of Long Island Manotick, 1827-1997 (North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 1997), iii, 1.

2. Carroll and Humphreys, 2.

3. Carroll and Humphreys, 6.

4. The Grist Mill

1. William Tupper and Georgina Tupper, The Dickinson Men of Manotick (North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2015), 61-62.

2. Felicity L. Leung, Grist and Flour Mills in Ontario: From Millstones to Rollers, 1780s-1880s (Ottawa: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, 1981), 72.

3. Carroll and Humphreys, 7.

4. Andrew Narraway. “I Am, Gentlemen, Your Obedient Servant”: Joseph Merrill Currier (1820-1884), (North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2009), 18.

5. Tupper and Tupper, 64-65.

5. The Carding Mill

1. Tupper and Tupper, 68.

6. The Carriage Shed

1. Joanna Dean and Lucas Wilson, “Horse Power in the Modern City,” in Powering Up Canada: A History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600, ed. R.W. Sandwell (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 101.

2. Dean and Wilson, 100-101.

3. Dean and Wilson, 102.

7. Willie Dickinson

1. Tupper and Tupper, 85-86.

8. The Dickinson House

1. Felicity L. Leung, Grist and Flour Mills in Ontario : From Millstones to Rollers, 1780s-1880s (Ottawa: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, 1981), 72.

9. The Dickinson Complex

1. Tupper and Tupper, 19.

2. Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates 5th Parl, 3rd Sess: Vol. 1 (24 March 1885).

3. Tupper and Tupper, 139.

11. The Iron Bridge

1. Narraway, 31.

2. Tupper and Tupper, 28.

12. Clapp Barns & Express Service

1. Tupper and Tupper, 41

2. Carroll and Humphreys, 16.

13. Second Sawmill from West

1. Tupper and Tupper, 73-74.

2. Tupper and Tupper, 80.

3. Tupper and Tupper, 82.

14. The Bung Mill

1. Tupper and Tupper, 56, 58; Carroll and Humphreys, 16.

2. Tupper and Tupper, 57.

15. Bessie Dickinson

1. Maureen McPhee, The Women of Dickinson House and Their Place in Manotick Village Society, 1870-1930 (North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2014), 33.

2. McPhee, 12.

3. McPhee, 16

4. National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, vol. 7, 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3).

6. McPhee, 27-28.

16. Memorial Park

1. McPhee, 22-23.

18. Dickinson Plaque

1. Tupper and Tupper, 31-32.

2. Tupper and Tupper, 32.

3. Tupper and Tupper, 33.

Bibliography

Carroll, Catherine and Barbara Humphreys. A History of Long Island Manotick, 1827-1997. North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 1997.

Dean, Joanna and Lucas Wilson. “Horse Power in the Modern City.” In Powering Up Canada: A History of Power, Fuel, and Energy from 1600, edited by R.W. Sandwell 99-128. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016.

Leung, Felicity L. Grist and Flour Mills in Ontario: From Millstones to Rollers, 1780s-1880s. Ottawa: National Historic Parks and Sites Branch, Parks Canada, 1981.

McPhee, Mauren. The Women of Dickinson House and Their Place in Manotick Village Society, 1870-1930. North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2014.

Narraway, Andrew. ‘I Am, Gentlemen, Your Obedient Servant’: Joseph Merrill Currier (1820-1884). North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2009.

National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, vol. 6810, file 470-2-3, vol. 7, 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3).

Stamp, Dora. Manotick Then and Now: Reflections and Memories. 2nd ed. North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2009.

Tupper, William and Georgina Tupper. The Dickinson Men of Manotick. North Gower: Rideau Township Historical Society, 2015.

Wilson, Ron. “The Rideau Canal at Manotick, Early Days.” Rideau Township Historical Society Newsletter, May, 2009. http://rideautownshiphistory.org/Newsletters/RTHS%20May%202009.pdf