Walking Tour

The Village of Alma

The Growth of Salmon River

By Natalie Dunsmuir

The small town of Alma first got its start in the early nineteenth century when Europeans settled here. The region's early economy consisted of logging, fishing, and shipbuilding. Alma, at the mouth of the Upper Salmon River, was well situated for these industries. The plentiful surrounding woodlands were logged, and the lumber floated down the river to the mill in Alma. Shipbuilders constructed boats on the town's shores, and fishermen built a weir to increase the profitability of the herring and shad fisheries. The town thrived.

Today, most of these early industries have faded away, though lobster and scallop fishing remains a major part of Alma's economy. Tourism has become integral to the town due to the presence of Fundy National Park across the river, and Alma is known for its plentiful seafood restaurants.

On this walking tour, we will explore the early identity and economy of Alma. At Stop One, on the hillside above the town, we will learn about the community's roots and initial settlement. Then, we will walk down School Street to the town's wharves and explore the history of shipbuilding in Alma. Stop Three, also on the wharves, goes deeper into this industry, looking at how early boats were built and how the industry transformed throughout the years. Stop Four is farther along the shore and delves into the town's fishing industry.

From here, cross Main Street and walk across the bridge over the Upper Salmon River. Pause at Stop Five to learn about the lumber and sawmill industry in Alma and at Stop Six on the other side of the bridge to discover the history of the original covered bridge that once stood on this spot. Walk along the boardwalk to learn about the ecology and geology of the Bay of Fundy and about the formation of Fundy National Park at Stop Seven. Finally, head over to the Molly Kool Centre across Main Street to learn about Alma's famous female sea captain, Molly Kool.

This project is a partnership with Fundy Tourism.

1. The Salmon River Settlement

1950

This photo from 1950 looks across the town of Alma towards the waterfront. To the left, the main houses and buildings of the village are arranged along School Street and Main Street. To the right, Alma's covered bridge leads towards the then-newly established Fundy National Park. The town of Alma began its life in the early nineteenth century as a logging and fishing community known as the Salmon River Settlement. Life centered on the seasons and the environment, and community was an important pillar of daily life.

* * *

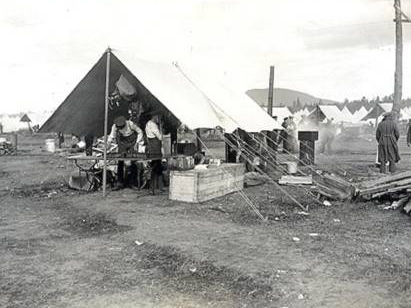

The original industries around which the small town of Salmon River revolved were highly seasonal in nature. In about 1840, a lumbering company from New Hampshire built a large sawmill at the mouth of the Salmon River. Men departed for lumber camps in the winter and spent long weeks felling trees, which were then stacked in so-called "log brows". As soon as spring came, the logs were floated down the Upper Salmon River to the mill, where they were sawn into lumber. The plentiful lumber supported the shipbuilding industry, as well as the sea trade of lumber being shipped to world markets, which employed many men.

Farming was necessary to the livelihood of all families, who raised livestock and planted gardens for food. The women, besides raising their families, also worked in the gardens, harvesting and preserving food for the winter. Fishermen harvested the plentiful shad and herring, which were exported on the trading ships. Salmon was also plentiful. Today, in addition to tourism, lobster and scallop fishing are important industries based out of Alma’s tidal harbour.

The small town changed its name in 1856, when the Parish of Alma was created. The new name was chosen to honour the 1854 Battle of Alma, which took place between allied expeditionary forces and Russian forces on the banks of the River Alma during the Crimean War. The village was officially incorporated in 1966, after governmental changes dissolved the traditional county system around which the region had previously been organized.

2. Albert County's Shipbuilding Industry

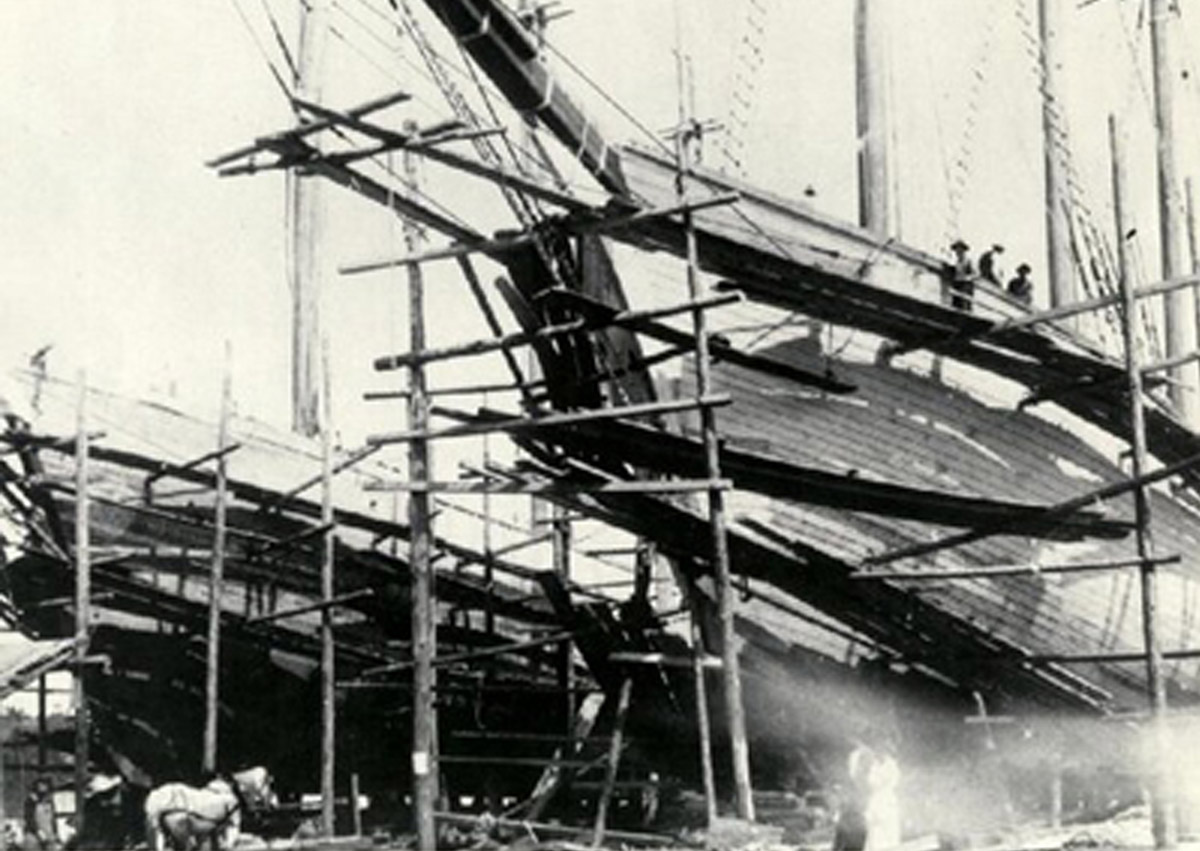

1918

This photograph shows the tall ships the Meredith A White and the Vincent A White under construction in Alma's harbour in 1918. Scaffolding surrounds the vessels to allow workers to finish the sides of the hulls. Note the small white horse to the left of the image, which provides a scale for the size of the vessels. The Meredith and Vincent were the last tall ships to be constructed in Alma, putting an end to an industry that had long been of integral importance to the region.

* * *

Alma wasn't the only spot in Albert County with a shipyard, though it was one of the most prominent. Along the Petitcodiac River and the shores of the Bay of Fundy, there were at least 23 shipyards scattered between Salisbury, to the west of Moncton, and Point Wolfe, southwest of Alma. The plentiful marshes, lowlands and mudflats provided ideal spots for boat construction, and many of the creeks that flowed into the Petitcodiac and the Bay of Fundy had shipyards at their mouths. Hopewell Cape, northeast of here, was particularly important for shipbuilding, and by 1874, 52% of the ship tonnage constructed in Albert County was constructed there.1

The two vessels pictured here were built for the company C.T. White and Sons Limited and were later launched at Apple River in Nova Scotia. They were named after White's children, Meredith and Vincent, and would go on to sail to South Africa.

3. How Ships Were Built

ca. 1900s

This photo shows Alma's busy wharves, with schooners and tugboats tied at the dock. Lumber is piled on the wharves, awaiting export. Many of the ships here were likely built in Alma or elsewhere in Albert County. Shipbuilding was a long, in-depth process overseen by a Master Shipbuilder. Albert County's shipbuilding industry lasted from the 1790s to the late 1910s, when new technologies and a changing global economy led to its demise.

* * *

The first step of the building process was to create a blueprint for construction. Rather than drawing this on paper, shipbuilders carved and constructed small wooden half-models to show the proportions and shape of the vessel. Only once this design was approved by the buyer did it go onto paper, and from there it was drawn onto the floor to-scale. The keel and frame were built based on these drawings, and planks and caulking affixed to them. The final touch to the hull was a paint which repelled both wood rot and barnacles. The deck and deck houses were then built, and the mast raised.

In Albert County as a whole, at least 330 ships were constructed throughout the nineteenth century, although the true number is likely much larger due to poor record keeping. This prolificacy was not to last, however. The rise and fall of the industry matched the so-called "Golden Age of Sail." Towards the end of the century, it began to decline in Alma and throughout the county. By the 1920s, it was gone.

This was due to a number of reasons, but chief among them was a change in shipping technology. Wooden sailing ships were being replaced by larger boats of steel and iron, powered by steam. Alma's shipyard had no way to make this switch—the industry was based around the area's lumber, and shipbuilders had no access to the necessary metals. Importing iron and steel was too expensive. Many of the shipyards across the Maritimes folded, and only larger shipbuilding centres such as those in Britain survived the modernization of the industry.

The other reasons for the closing of Alma's shipyards were based on global markets. Demand for new boats fell, and prices for cargo shipping declined. Bigger boats became more profitable, as more cargo could fit in one vessel. Alma's yards specialized in smaller vessels and therefore got left behind. Furthermore, the British Isles stopped prioritizing the markets of its colonies, so access to this lucrative market was no longer guaranteed. The last vessels were built in Alma in 1918. The town's economy took a hit.

4. The Fishing Industry

Library and Archives Canada 1971-271 NPC

ca. 1960s

In this photo from the 1970s, a family of three, with a man, woman and small child, pose beside a stack of lobster traps. The man holds a live lobster in his hands. Lobster has become part of Alma's cultural identity and is available in most of the town's many seafood-based restaurants.

* * *

Alma's location on the shores of the Bay of Fundy has shaped its identity. Life for many of its residents revolves around the sea. Alma's tides, the largest in the world at up to 14 metres high, make fishing an intense process. Fishermen can not keep daily schedules but must live their lives around the tides, even if this means leaving the wharves in the middle of the night or the early morning. Fleets of boats take to the water as soon as there is enough water to do so and return as the tide goes out again. Misjudging the tides could mean stranding your boat on a sandbar far from shore.

In the early years, fishing, along with farming and gardening, kept new settlers fed all year round, allowing the region to be nearly self-sustainable. When the lumber industry and the shipbuilding industry collapsed, the fisheries were still there. Originally, Alma's fishing industry centred on herring, salmon, and shad. A weir was built in 1840, adapted from First Nations herring weirs, to increase the productivity of these fisheries.1

Yet the intense tides of the region are not the only challenge Alma's fishermen have had to face. Towards the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, pollution threatened to destroy the fishing industry. Refuse from the area's sawmills clogged the Upper Salmon River and the Bay of Fundy, crushing the herring fisheries and devastating the population of Atlantic Salmon, who were unable to make it up the rivers to spawn. Particularly bad was the sawdust that clogged waterways. An 1889 government report on the problem described beds of collected sawdust in New Brunswick's waterways as "a long, continuous mantle of death."2 The fishing industry declined, and the population of Alma and nearby communities with it.

Gradually, however, the industry came back, especially as the logging industry collapsed and the sawmills shut down. Today, an annual festival kicks off the start of lobster season every autumn, and the town also hosts a chowder festival each year that pits local restaurants against each other to create the best seafood chowder.

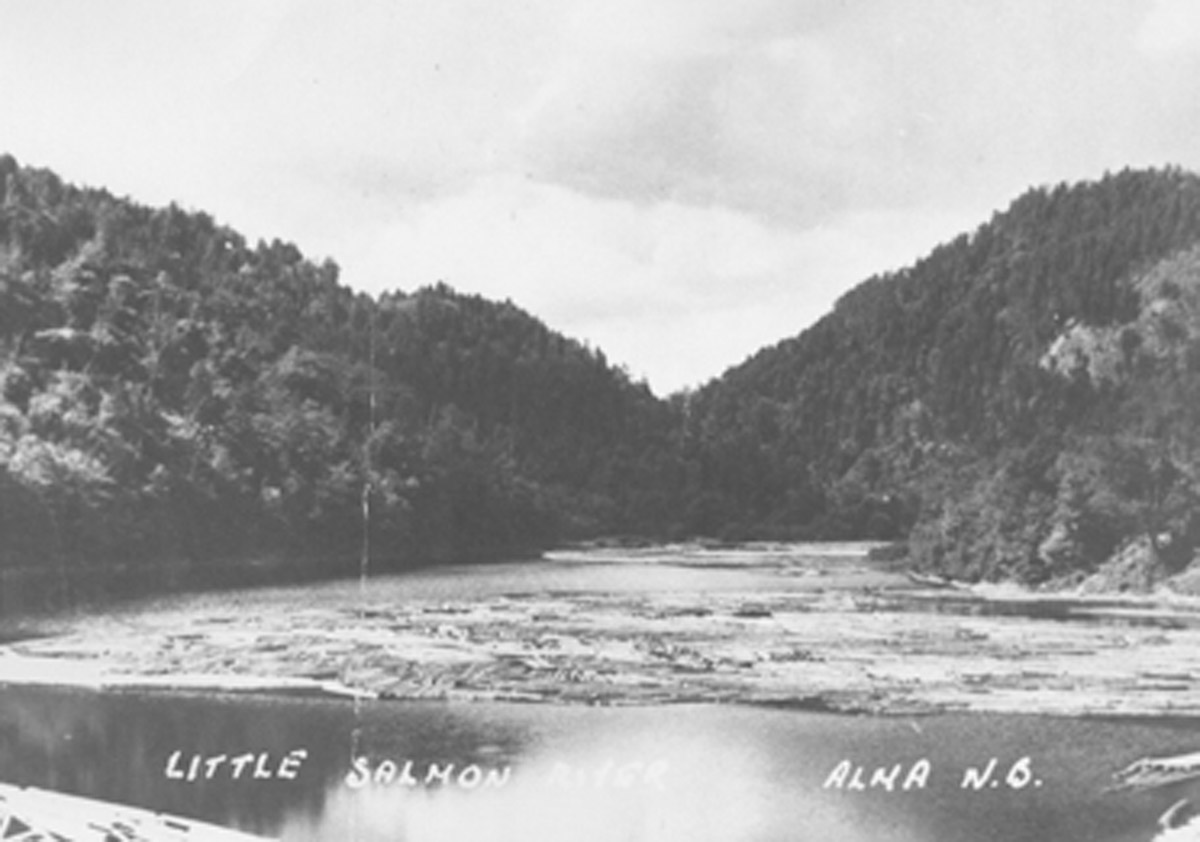

5. Logging in Alma

This photo shows a log jam on the Alma River during spring, when timber cut in the winter logging camps was floated to the mill at the river's mouth to be processed and shipped to market. Logging was a major industry in Alma from the town's founding in the early nineteenth century all the way until the mid-twentieth century. The cycles of the industry defined the lives of many Alma residents, and the highs and lows of the lumber economy shaped the town's prosperity.

* * *

Throughout Albert County in the early nineteenth century, sawmills and lumber camps sprung up, located on dozens of the rivers and creeks that ran into the Bay of Fundy and the Petitcodiac River. By 1851, there were 97 sawmills in the county, though many of these were small operations that cut timber within a few square kilometres of the mill. The largest mills developed at Alma, Point Wolfe, the Pollett River, and Crooked Creek. These mills grew to process between 5 and 6 million board feet of wood every year.

Logging was a dangerous, intensive job. Loggers lived in work camps in the woods for weeks during the winter months, cutting trees with axes or with two-person cross-cut saws. White pine was prized for ships masts, although tamarack and spruce trees were also cut. After they were felled, trees were dragged by teams of horses to form large piles on the river banks that often grew to cover the entire slope of the valley.

In the spring, the job grew even more dangerous. A dam, built above the lumber camps, would collect melt waters. When the water began to reach the top, men would open the gates and a massive flood would sweep down the river valley, picking up the waiting logs on the banks. Men would push any logs that the waves missed into the current before it had a chance to subside. In this way, the season's timber supply would reach the mill at the river's mouth for processing. It would then be milled and loaded onto the ships waiting in Alma's harbour.

The logging industry in Alma lasted well into the twentieth century, but it began to decline towards the end of the 1800s. By then, most of the easily accessible timber had been cut and the shipbuilding industry was crumbling. Most of the large mills closed by 1922, as lumber barons eyed the northwest of Canada for fresh supplies of untouched forest. The sawmills that did still exist converted to steam or gas power rather than water, and smaller, portable sawmills replaced many of the larger operations. The last log drive in Alma took place in 1951.

6. The First Female Deep Sea Captain

The Molly Kool Centre, pictured here, celebrates the life and legacy of Molly Kool, North America's first female deep sea captain. The Centre is housed in Molly's restored childhood home and is filled with exhibits that tell her fascinating story.

* * *

When Molly graduated high school, she had few options for work; it was the 1930s and the Great Depression was lying heavy on the country. Jobs were scarce, so Molly went to sea with her father, working on his boat, the Jean K, which was named for her older sister. After working on the scow with her father for two years, she decided to enrol in the Merchant Marine School in Saint John to earn a Mate’s license, even though no woman had ever done so before. She knew that if she got her Mate’s license, she could then work towards obtaining her Master’s certificate. She passed her Mate’s license with distinction and returned to work on the Jean K as Mate Molly Kool. After two years, the time came for Molly to put in her application at the Marine Institute in Yarmouth for her Master’s certificate. Her application was refused, but Molly applied again, only to receive another refusal, this time stating that women were not allowed to apply because there was no “she” in the Canadian Shipping Act. Molly persisted, and the Shipping Act was changed to be gender neutral, so her application was accepted. Molly passed her exams and graduated with her “Master’s Certificate of a Cargo Steamship in the Home Trade”, becoming the first woman in North America to attain this title. Molly sent a telegram home reading, “Call me Captain from now on.” 1

After this triumph, Molly returned to Alma to captain the Jean K. Her father retired, and she took over the family business. For five years, she sailed on the treacherous waters of the Bay of Fundy, with its extreme tides, currents and weather. Over the years, she earned a reputation as a fierce and capable captain.

Yet Molly's sea career was relatively short. When she had been captain for five years, a gasoline explosion in the Jean K caused extensive damage to the boat. It was sent for repairs in Maine, and Molly intended to continue as captain when it returned. However, her time on land waiting for it must have made her change her mind. Molly retired after five years at sea, got married, and moved to Maine, where she lived for the rest of her life. She died in 2009, and her ashes were scattered in the Bay of Fundy.

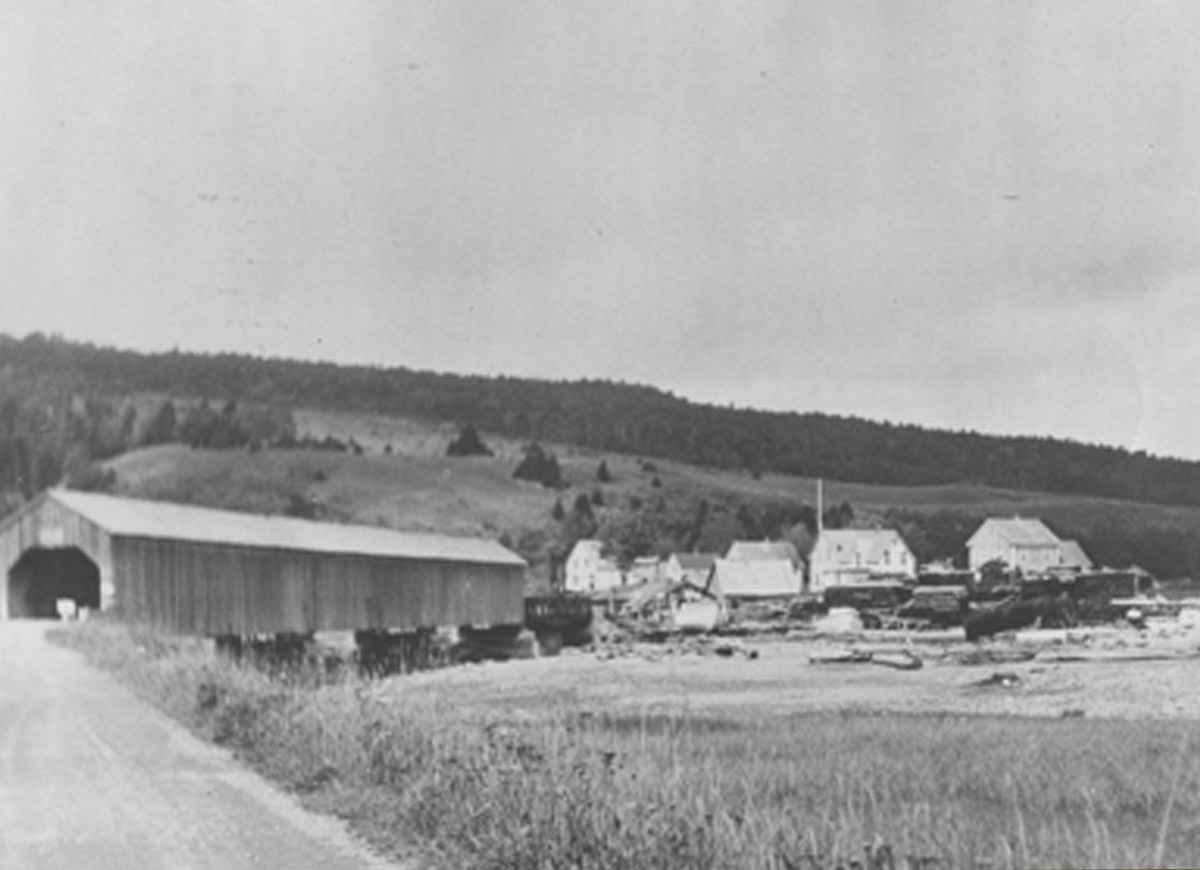

7. Albert County's Covered Bridges

The covered bridge in this photograph stood in Alma for many years. Here, the bridge is shown from the west looking across the river to the main Alma townsite. Covered bridges like this one were constructed all across New Brunswick in the thousands, though today, only 58 remain in the province. Alma lost its covered bridge in the early 1970s when it was dismantled and replaced with a more modern construction of metal and concrete.

* * *

As for why the bridges were covered, the answer is quite simple: covered bridges lasted longer. The ceiling and walls protected the roadway from the elements. Since the bridges were wooden, they were highly susceptible to rot. A bridge left uncovered would last around ten years. A covered one could last more than eighty years, and longer with the right repairs and reinforcements. Covered bridges are not only a New Brunswick phenomenon either—they can be found across Europe and North America in places where wood is abundant and the weather fierce.

Constructing a covered bridge was difficult. The timbers were first felled and shaped by local labourers, then the frames assembled on land in order to "test" the bridge. Afterwards, builders created stone abutments on the river banks to act as the bridge's foundation. The roadway of the bridge was erected over the river first, the siding and roof later on, often after the bridge had already opened to car and wagon traffic. Most bridges were left unpainted, since the siding was high quality, seasoned wood and therefore did not need the protection of paint. Some bridges were given windows to let in light, particularly after the rise of cars increased the risk of head-on collisions on the one-lane bridges. After the completion of a bridge, builders would test it by driving a team of cattle across it.

Depending on the length of the bridge and the difficulty of the terrain it was built upon, teams of builders could range from three to thirty men. The cost of a bridge was, on average, around $1,050, or about $35,000 in today's dollars once inflation is accounted for.1 One man and a pair of horses was paid $2.20 (around $77 dollars today) for a ten-hour shift. A man and an oxen team had the wage of about $2 ($70 dollars today) per shift.

Today, efforts are being made to conserve the last of New Brunswick's remaining covered bridges. While the Alma bridge did not survive, others have. Just down the road in Hopewell Hill, the Sawmill Creek Bridge was recently restored with a new roof.

8. Alma's Environment

This photograph shows Alma's harbour with lumber piled on the wharf and a two-masted ship ready to be loaded with timber. While the town's early economy focused on resource use and harvesting, this later evolved into a focus on tourism and the environment. Where lumber was once piled, popular seafood restaurants and gift shops now sit. The boardwalk you stand on is a testament to this changing attitude. It was built to protect the shoreline from erosion and allow tourists to better experience Alma's extreme tides.

* * *

These high tides create unique ecosystems for shorebirds and marine life. The expansive mudflats of low tide are a feeding ground for shorebirds such as the semipalmated sandpipers who stop to rest and feed here each summer during their migration from the Arctic. The Alma tidal flat extends up to one kilometre during its lowest tides, and animals such as mud shrimp and clams thrive here.

These unique environments have faced many challenges over the years. During the height of the logging boom in Alma, debris from sawmills and other pollution devastated the environment surrounding the town. Yet in 1948, the area became the site of New Brunswick's first ever National Park. The land previously occupied by lumber barons was instead transformed into a tourism and conservation area. The park officially opened in July of 1950 with the goal of protecting the environment and helping out Alma's fragile economy, which had suffered for decades due to the decline of logging and the loss of the shipbuilding industry.

Today, nearly 300,000 people visit Fundy National Park each year, and tourism makes up a major part of Alma's economy.

Endnotes

1. The Salmon River Settlement

1. "Fundy National Park: History." Parks Canada, Government of Canada. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nb/fundy/culture/parc-national-park/histoire-history.

2. Albert County's Shipbuilding Industry

1. "The Shipbuilding Industry." Albert County Museum and RB Bennett Centre. https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/shipbuilding.

4. The Fishing Industry

1. "History of Fishing in Canada." Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters. http://www.fishharvesterspecheurs.ca/fishing-industry/history.

2. Allardyce, Gilbert. "'The Vexed Question of Sawdust': River Pollution in Nineteenth Century New Brunswick." The Dalhousie Review, vol 52, issue 2, pp. 177-190.

6. The First Female Deep Sea Captain

1. "Molly Kool." Albert County Museum and RB Bennett Centre. https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/molly-kool.

7. Albert County's Covered Bridges

1. "Covered Bridges: A Part of New Brunswick's Heritage." Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, 2021. https://archives.gnb.ca/exhibits/CoveredBridges/Introduction.aspx?culture=en-CA.

8. Alma's Environment

1. "Bay of Fundy: The Highest Tides in the World!" BayofFundy.com, 2021. https://www.bayoffundy.com/about/highest-tides/.

Bibliography

Allardyce, Gilbert. "'The Vexed Question of Sawdust': River Pollution in Nineteenth Century New Brunswick." The Dalhousie Review, vol 52, issue 2, pp. 177-190.

"Covered Bridges: A Part of New Brunswick's Heritage." Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, 2021. https://archives.gnb.ca/exhibits/CoveredBridges/Introduction.aspx?culture=en-CA.

"Fundy National Park: History." Parks Canada, Government of Canada. https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nb/fundy/culture/parc-national-park/histoire-history.

"History of Fishing in Canada." Canadian Council of Professional Fish Harvesters. http://www.fishharvesterspecheurs.ca/fishing-industry/history.

"Molly Kool." Albert County Museum and RB Bennett Centre. https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/molly-kool.

Shortt, Kirstin. "A Brief History of Alma." Connecting Albert County: Culture and Heritage, April 32, 2020. http://www.connectingalbertcounty.org/culture--heritage/a-brief-history-of-alma.

"The Lumbering Industry." Albert County Museum and RB Bennett Centre. https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/the-lumbering-industry.

"The Shipbuilding Industry." Albert County Museum and RB Bennett Centre. https://www.albertcountymuseum.com/shipbuilding.