Walking Tour

A Tenacious Community

The Acadians of Albert County

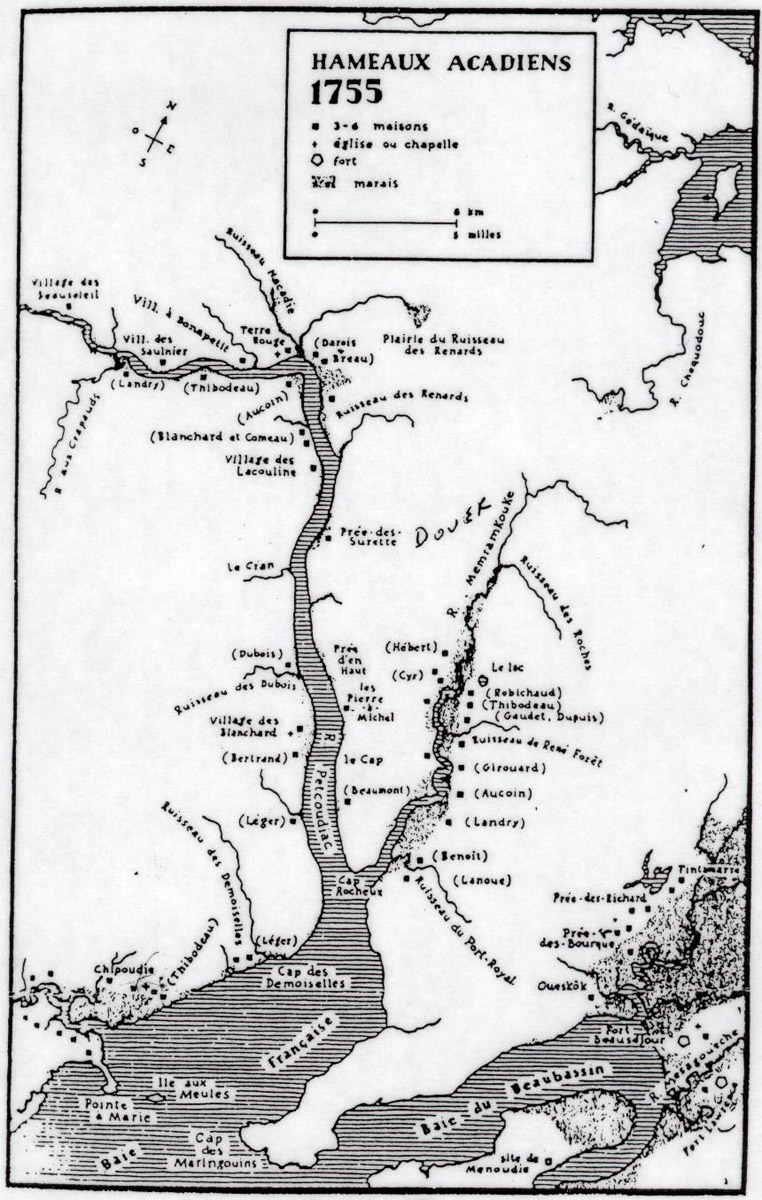

Who were the Acadians of Albert County? Where did they live? What were their daily lives like before they were deported from the Maritimes during Le Grand Dérangement (The Great Expulsion)? During this On This Spot highway driving tour through present-day Albert County, New Brunswick we will meet the Acadian families who lived in this area, which the Acadians called Trois-Rivières, prior to and during the Expulsion.

Each tour stop will introduce you to an Acadian family and give you a glimpse into their daily lives and culture. We will end by learning about the ongoing efforts to commemorate the families that lived in Trois-Rivières.

Please remember that in Canada, the use of handheld devices while driving is prohibited by law. Press play on this audio tour before you start driving and keep your eyes on the road.

This project is a partnership with Fundy Tourism.

1. La Pointe-Du-Coude

If you are beginning this tour from Moncton, head southeast on Vaughan Harvey Boulevard, crossing the Gunningsville Bridge. At the first intersection after the bridge, turn left onto Highway 114. Travel along the highway for 1.5 km, then turn left onto Point Park Drive. At the intersection of Point Park Drive and Avondale Drive, turn left. Facing you at the end of Avondale Drive is a large pullout. Park here. This was the settlement of Pierre Saulnier and Madeleine Comeau and the beginning of our tour.

* * *

The Acadians are the descendants of the French settlers who arrived in the French colony of Acadia in 1604. Some are also descended from French settlers and local Indigenous people—the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqiyik, and the Peskotomuhkati. Acadia encompassed mainland Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, along with some parts of Québec and the state of Maine. The colony was formed primarily in Mi’kma’ki, the territory and homeland of the Mi’kmaq people. Mi’kma’ki includes all of present-day Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, as well as most of New Brunswick, the Gaspé Peninsula, and Newfoundland.1 Western New Brunswick and parts of Maine are the homelands of the Wolastoqiyik and the Peskotomuhkati.

The original French settlers were not Acadian—we can only speak of Acadians and an Acadian culture when referring to subsequent generations. While some food, clothing styles, celebrations and more were passed down from their French ancestors, Acadians also adopted traditions and ways of living from the Mi’kmaq whose land they settled on. They learned how to build and use canoes to navigate rivers, how to make shoes from animal hides and more.

In 1737, Pierre Saulnier, the son of Pierre Saulnier and Madeleine Comeau, settled on this spot. He was engaged to Madeleine Hache, the daughter of Michel Hache and Madeleine LeBlanc. The couple built a home on the downstream side of a brook and were married a year later. Eventually, Pierre and Madeleine were joined at this location by Pierre’s sister Anne, who was married to Jean-Baptiste Aucoin, the son of Charles Aucoin and Anne-Marie Martin.

In 1755, during the Expulsion of the Acadians, three British ships arrived here and set fire to the houses, barns, and crops.

In the next segment of this tour we will travel to the area known by the Acadians as Les Anses de l'aval. This is where François Martin and François Comeau established a settlement in 1723.

2. Les Anses de l'aval

François Martin and François Comeau settled on this spot in 1723. Martin chose to settle near the larger of the creeks, which had more marshland, while Comeau chose the smaller creek for its better meadow. Martin married Angélique Bertrand, who gave birth to a son. Tragically, Martin died less than two years after their marriage. Angélique then married Toussaint Blanchard, and the couple took over the property. Due to a lack of land in the area, the sons of Martin and Comeau chose to establish themselves in Grand-Prée.

* * *

The family and the household formed the basis of daily life for Acadians. Kinship ties also impacted relationships with others in the community. Most marriages occurred between Acadians whose families had been settled in L’Acadie for a generation, but it is estimated that 25% to 30% of marriages were formed between an Acadian and someone from another place, like Québec or France. Marriages also took place between Acadians and the Mi’kmaq, whose lands the original immigrants from France had settled on. Some Acadian families married each other often—Blanchards, LeBlancs, and Landrys frequently intermarried, as did members of the Trahan and Granger families.1

Most Acadian families were large, but the number of children in a family depended on how old a woman was when she married. Those who were younger than twenty when they wed usually had 10 or 11 children, while a woman who married in her late 20s would have seven or eight. This high birth rate meant that multi-family households would welcome a new baby almost every year.2 Family was an important aspect of Acadian life, as demonstrated by a court case where grandparents fought over who would be able to raise a child born out of wedlock.

Outside of the area around Port-Royal (now Annapolis Royal, NS), family was critical in determining the creation of settlements. There was no official survey work carried out along the Petitcodiac and Shepody Rivers. Instead, agreements between Acadian settlers regarding land use were structured and shaped by family ties.

Often, one or two households would leave an area to establish themselves elsewhere before sending word to members of their extended family to join them. Fathers could permit their sons-in-law to build homes near theirs, while uncles could do the same for nephews and their households.

3. La pree-des-Lacouline

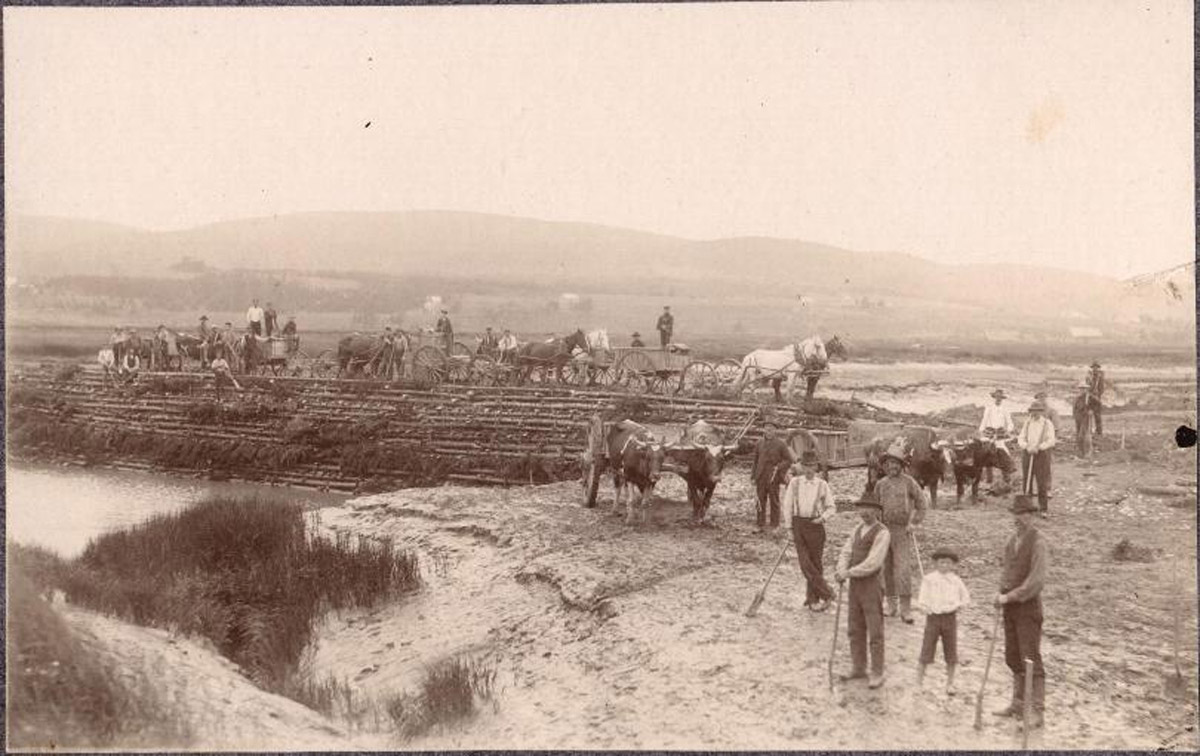

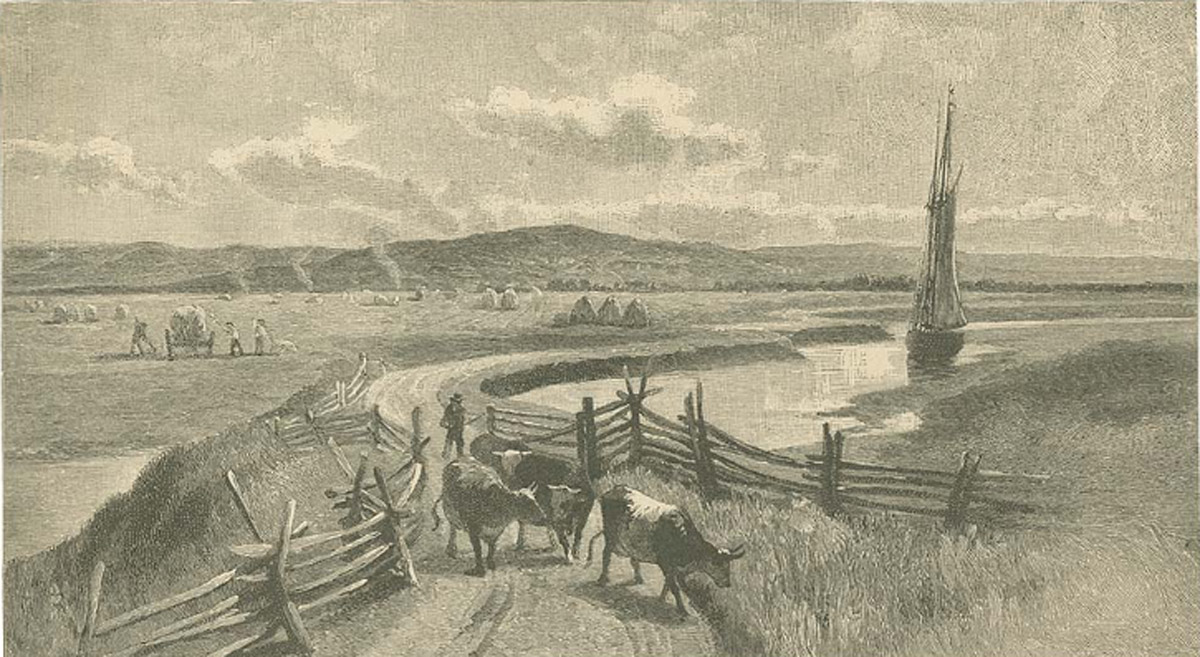

Acadians built dykes in order to use the fertile marshlands for farming. This photo of a group of men, oxen, and horses constructing a dyke on Shepody Marsh in 1870 illustrates how labour-intensive they were to build.

Around 1738, brothers Pierre and Joseph Saulnier, along with their fiancées, the sisters Marie and Isabelle Boudrot, dyked the marsh and built their homes on this spot. Claude, the younger brother of Pierre and Joseph, also helped improve the land for farming, and in 1750 he and his fiancèe, Françoise Aucoin, built a home here as well. The couple wed two years later.

The Saulnier family also had the nickname of Lacouline, which is where the name of this settlement came from.

* * *

Mutual aid and cooperation was critical to survival for the early Acadians. The most enduring of these cooperative projects are the dykes that have permanently altered the topography of present-day New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Many are still present and visible today. The system of dykes surrounded the lands of several families, which meant that whole communities had to work together to build and maintain them.

Many of the early French settlers, who were the ancestors of the Acadians, came from lowland regions of France where the inhabitants were already using dykes to reclaim marshlands for agricultural activities—these areas include Poitou, Vendee, and Saint Onge.

However, when it came to the Bay of Fundy, the Acadians had to modify their practices due to the tides being among the strongest in the world. These powerful tides were what made the soil of its salt marshes so fertile, but in order to be able to use this land for farming, the Acadians had to deal with the flooding caused by the high tides.

To drain and desalinate the fertile marshlands, Acadians built a series of drainage ditches and each was equipped with an aboiteau—a one-way water gate that opened and closed automatically with the movement of the tides. The aboiteau allowed fresh water to be drained from the marshland at low tide while also preventing salt water from flowing into the farmland during high tides.

The system of dykes and aboiteaux was so complex to maintain that after the Deportation, the English had to release some of the imprisoned Acadians to maintain the dykes and prevent the marshlands from being reclaimed by the sea.

4. LeCran

Another of Samuel Scott’s 1751 paintings of Acadian life, this image depicts an Acadian homestead and farm. The settlement on this spot was named "Le Cran" because the homestead and farm were located in a natural notch, or cran, in the cliffs.

In 1739, Paul Martin, the seventh son of Grand-Pierre Martin, confronted Jean DuBois. DuBois was occupying land that had been claimed by Paul’s brother, François Martin of Les Anses de L'aval. The disagreement was resolved by forming kinship ties: Paul and Geneviève DuBois, Jean’s daughter, were married and settled on this spot. DuBois also promised to help develop neighbouring land to the south.

Another of Paul’s brothers, named Pierre Martin after his father, moved to Le Cran in 1745. When Paul died a few years later, Geneviève married Joseph Gaudreau and the two continued to develop the farm in the notch.

During the Expulsion, a traitor named Daniel told the British the location of the homes and farm in the notch, and British soldiers set fire to the entire settlement.

* * *

Acadians depended on what they could grow and raise on their land and the dykes that allowed the fertile marshlands to be farmed. Daily life for everyone changed with the seasons—ploughing, planting, and harvesting are all seasonal activities.

Reading the accounts of travellers from the seventeenth century gives us a glimpse into what kinds of fruits, vegetables, and grains were grown by the early Acadians. Cabbage, turnips, onions, shallots, carrots, and beets are some of the vegetables listed. The Acadians also grew a number of grains that were common to Western Europe at the time, including wheat, oats, rye, barley, and peas. They also grew hemp and flax. Many families also had orchards that grew apples, pears, cherries, and plums.1 During his travels to Acadia in the late 1750s, Captain John Knox wrote that “finer flavoured apples and greater variety, cannot in any other country be produced.”2

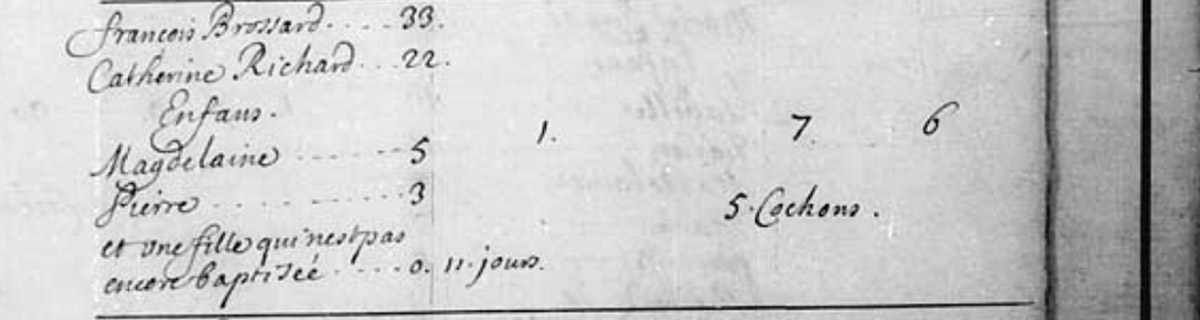

Raising livestock was also important to sustaining life in early Acadian settlements. The 1698 Port-Royal census shows this clearly—in addition to noting the amount of land each household held, there are columns tallying the number of pigs and sheep. Pigs added protein to the Acadian diet, and sheep were raised for their wool. Poultry provided meat and eggs, but feathers could be used to make down-filled mattresses and coverlets as well. Some families were able to raise enough livestock that they could trade with other settlements like Louisbourg.3

5. La Pres-des-Dubois

This photo shows a mosaic representing the Vincent family. It is part of the mosaic sidewalks at the Acadian Memorial Meditation Garden in St. Martinville, Louisiana. The Vincent family's shield includes a cross to represent the Catholicism of the Acadians, which is a common symbol in the shields of many Acadian families.

This is the land that Paul Martin and Jean DuBois had a disagreement over. Paul’s brother, François, attempted to settle here before settling Les Anses de l'aval instead.

DuBois and his wife, Anne Vincent, began preparing the land for farming in the late 1720s before moving here with their children in 1730. Anne later gave birth to Paul, Olivier, Honoré, and Alexis. Another of their sons, Jean-Pierre, became engaged to Hélène-Josephe Celestin, and the couple built their home on the north bank.

* * *

Like their French ancestors, the Acadians were largely Catholic. Though originally part of the Beaubassin parish, a church dedicated to Our Lady of the Visitation was built in Chipoudie sometime before 1740. Some nineteenth-century historians have indicated that this church was built on Hopewell Hill, northeast of the Ruisseau de l'Église (Church Creek).1 The church was burned down by British soldiers on September 1st, 1755 but a new chapel, built by the Chipoudie residents who had fled from the British and hid in the woods, was in place by March 1756.2

Most of the smaller settlements, like those in what is now Albert County, did not have resident priests and instead were visited by one annually 3. Priests would also be encountered when they presided over marriages, baptisms, and funerals. Acadians considered themselves good Catholics, but were as unwilling to submit totally to Church authorities than they were to political authorities.

Perhaps this distance from religious authorities played some role in the behaviour that so upset the archdiocese of Quebec in 1742. He complained bitterly that in some Acadian settlements, bars were open on Sundays and even during Mass. He also expressed his outrage that some communities allowed men and women to dance together after sunset while in others des chansons lascives (lascivious songs) were sung.

6. Le Village-des-Blanchard

This photo, taken in the 1920s, shows the monument commemorating the Battle of the Petitcodiac shortly after it was erected.

Recruited by Pierre Thibeaudot in 1698, Guillaume Blanchard was one of the first known Acadians to settle in this area. It was decided that he would settle lands between Chipoudie and Memramkouke (Memramcook). Present-day Hillsborough was where Blanchard established a village.

In 1699, Blanchard’s daughter Jeanne married Olivier Daigle, who joined Blanchard and his sons in dyking the marshland here. In 1704, English raiders attacked and burned the settlement, but it was rebuilt.

On September 4th, 1755, the village was the site of the Battle of Petitcodiac between British colonial troops and Acadian resistance fighters protecting themselves and their families from deportation.

* * *

With the winter came more time for social activities like singing, dancing, and storytelling. Acadians observed many Catholic feast days, such as Christmas, Easter, and All Saints Day, but it was Candlemas Day in early February that was celebrated the most. A feast and a dance would take place in one of the houses in the settlement or village; in eastern New Brunswick celebrations, most of the food that was collected ahead of the feast was set aside for a family in need.1

Another type of celebration took place in the warmer seasons. A frolic was a kind of celebration that focused on the community coming together to do their yearly chores, like wood cutting.2

Christmas was celebrated before the Expulsion, though not much is known about what this may have looked like. We do know that celebrations were quite simple. Some merchants continued to keep their shops open on Christmas Day, perhaps because the main focus of Christmas celebrations was Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve.

One Christmas tradition that was likely brought over from France was the baking of naulet—a type of Christmas cookie shaped like a doll and given to children. Though they look similar to gingerbread men, naulet was made from a white pastry like bread or sugar cookie dough. They were often decorated with raisins.3

7. The Battle of Petitcodiac

This is the marsh where the Battle of Petitcodiac took place in September 1755.

As part of the Grand Dérangement, nearly 200 British soldiers were dispatched to destroy all of the Acadian settlements along the Petitcodiac River and round up the inhabitants for deportation to the American colonies. Under the command of Major Frye, these forces burned the settlement at Chipoudie before moving up the river towards other villages.

* * *

The Battle was a resounding defeat for the British. Even after the remainder of the troops under Frye arrived at the scene, the British could not gain the upper hand. After three hours of armed conflict, they were forced to withdraw. This victory against the British meant that nearly 200 Acadian families in the Trois-Rivières area (the settlements along the Petitcodiac, Memramcook, and Chipoudy Rivers) were able to escape deportation for the time being.

8. La Pree-Des Bertrand

This seventeenth-century engraving by Claudine Bouzonnet-Stella depicts a group dancing le branle, a popular form of dance in France at the time. Le branle de Poitou is a folk dance from the region of Poitou that was adapted into the minuet by the French court. Many of the Acadian families of New Brunswick are descended from French settlers who came from Poitou.

Originally settled by the Bertrand family, this site was then abandoned until the mid-1720s. At that time, Jean Bertrand, his wife Françoise Léger, and her brother P’tit Jacques Léger returned and dyked the lands upstream and downstream before building homes.

The settlement on this spot was expanded in the 1740s when Bertrand’s daughters, Marguerite and Madeleine, arrived with their husbands, Claude Paul Brasseur and Joseph Pinet.

* * *

Many of the dances found in Acadian communities before the Deportation were ones that had been brought over from France. Some of these dances were done in circle and chain formations where all the dancers would join hands and move in unison. According to Barbara Le Blanc, some of these dances “did not encourage individual accomplishment, but instead re-enforced adherence to the group and egalitarian social relations among community members.”1

A specific type of chain dance that was most likely brought to Acadia was the branle, a term which is derived from the French verb branler which means “to sway” and refers to one of the motions of the dance. Originally a rustic folk dance, a number of the French provinces had their own type of branle. The Poitou branle, for example, was danced in triple time.2

The branle was performed by alternating large sideways steps to the left, followed by an equal number of smaller steps to the right. Through these steps the chain of dancers would move slowly to the left in a circular or serpentine figure.3

9. L'Anse-des-LaRosette

This mosaic shows the family shield of the Louisiana descendants of the Léger family. The gold star represents Our Lady of the Assumption, the Patroness of the Acadians.

The settlement established on this spot gets its name from the nickname of the Léger family: Larosette. The Léger family was also sometimes known as the Richelieu family. Today this area is known as Edgett’s Landing.

In 1735, Jacques Léger and his son P’tit Jacques Léger (Jacques the Younger) colonized the cove. They were joined later by two sons of P’tit Jacques, Jean-Baptiste and Joseph. Joseph was married to Claire LeBlanc, and Jean-Baptiste was married to Madeleine Saulnier, who sadly died at just 25 years old. After the Expulsion, Jean-Baptiste wed Marie Cécile Poirier in Saint-Jacques (Saint James), Louisiana.

* * *

Bread and other grain-based foods were staples of the Acadian diet. Most of the various grains grown by Acadians were ground at community grist mills, but each household had mortars and pestles to grind coarse flour to make porridge with. Bread was baked at home and pancakes were also common. Buckwheat pancakes were commonly eaten and this tradition may have been brought to Acadia by settlers from the French regions of Normandy or Ille-et-Vilaine.1

Acadians also ate a kind of doughnut; according to a 1744 document these doughnuts were referred to as croxsignoles.2 This may be an alternate spelling of croquignole, a dessert of French origin that also exists in different forms in Louisiana and Quebec. It may have been brought to Louisiana, where it is known as a croquesignole, by the Acadians who moved there after the Deportation.

In Louisiana croquesignoles are called ‘French donuts’ by the English-speaking population. They are always square or rectangular in shape, are dusted with powdered sugar, and most often made in the winter.

Another staple of Acadian cuisine was a beverage that was enjoyed daily by eighteenth-century Acadians: spruce beer. They claimed the drink made them healthier, and it most likely did. The process of brewing beer would have killed any bacteria present in the water, and fresh spruce is a natural source of vitamin C. Using evergreen plants like spruce and pine to prevent scurvy was a practice developed by Indigenous people living on Turtle Island (North America) who then taught French explorers to do the same. The Acadian tradition of spruce beer was probably passed down by the first French settlers in Acadie.

Recipes varied, but one version of Acadian spruce beer was made from a base of rye, wheat, spruce, dandelions, and hops. Then water, yeast, and molasses would be added. A recipe from 1757 states that the tops and branches of the tree were used. These were to be boiled for three hours, strained, and then added to casks with molasses. Once it was cold it was ready to drink.

10. La Pree-Des-Brun

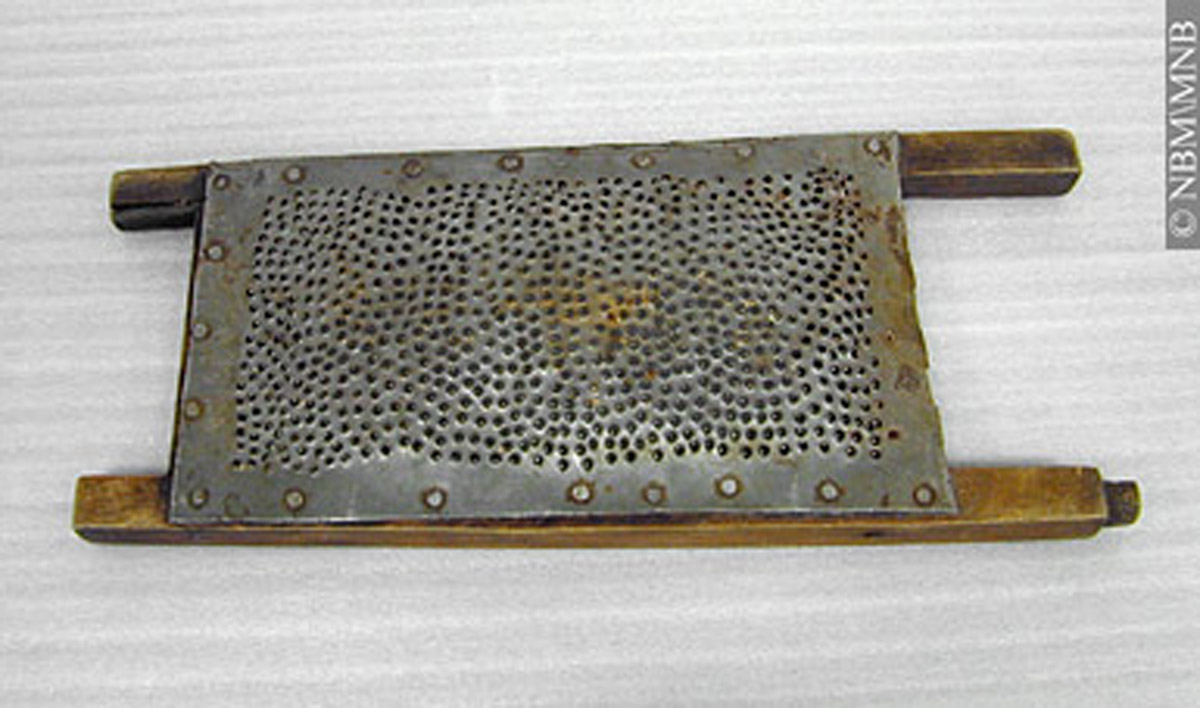

This photograph is of a potato grater circa 1800. The wooden parts of the grater are made out of chair legs, demonstrating that Acadians created tools and kitchen instruments out of what they had on hand. It is still debated whether Acadians had potatoes before the Expulsion or not, but potatoes are now central to what we know as Acadian cuisine.

Brothers François and Jean-Baptiste Brun reclaimed the marshes and settled on this spot in 1740. After the death of his father, Joseph Laurie settled in this area as well.

* * *

Not a lot is known about particular dishes that were prepared and eaten by the Acadians prior to the Deportation, but we do know that pigs were an important part of every farm. Pork fat was a staple of pre-Deportation Acadian cuisine. It was often cooked with cabbage in the winter, but it could also be fried and added to the vegetables that were seasonally available or that a family had on hand at any given time.1

Pork fat was also used in a wide variety of other dishes such as soups, meat pies, fish cakes, and even desserts. One such dessert was a pork fat and molasses pie. Fresh or salted pork covered in molasses was also eaten on bread.

A debate continues to this day about the place of potatoes in Acadian diets prior to the Deportation. Potatoes were not routinely eaten in France until the 1790s or early 1800s due at least partially to a fear that potatoes could cause leprosy. Historian Naomi Griffiths has found some sources which claim that potatoes were popularized as a foodstuff in France by Acadians who landed there after the Deportation, but it is the French pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier who has been publicly credited with revolutionizing the French attitude to potatoes.2

Regardless, potatoes were a critically important crop for the Acadians who returned to New Brunswick after the Deportation. These Acadians could not return to their own farms and were not permitted to settle on land with fertile soil. Potatoes were one of the only crops suited to this new land and they form the backbone of what we consider Acadian cuisine today.

One of the most iconic Acadian dishes, poutine râpée, unites the staples of both pre- and post-Deportation cuisines by combining pork and potatoes. Poutine râpée is particularly popular in the region around Moncton and consists of dumplings made from a combination of grated and mashed potato with salt pork in the centre. Traditionally the dumplings were boiled for three hours and served with molasses.

11. L'Anse-DesDamoiselles

This is an inset of the 1686 Port-Royal census showing the information collected about the Broussard family. While living in Port-Royal, the family had one rifle, six sheep, and five pigs.

Before settling at L’Anses-des-LaRosette, P’tit Jacques Léger joined Jean, Joseph, and François Comeau, along with Jacques Laurie, in colonizing the Cove des Demoiselles. A few years later, sisters Marguerite and Agnès Thibodeau moved to this spot with their fiancés, the brothers Alexandre and Joseph Broussard.

Just a few days before the Battle of the Petitcodiac, English soldiers anchored in Cove du Barnabe. The soldiers travelled north to this spot and burned the homes, barns, stables, and crops.

* * *

As we can see, waterways impacted and shaped Acadian history. The sea provided food, communication, and along with agriculture, structured seasonal work. The high tides of the Bay of Fundy in the fall and spring, for example, dictated when the building and repairing of dykes could take place.

We can see how important the sea was to the Acadians by looking at their language. An Acadian vocabulary was compiled in 1746 that contained only maritime words with an explanation of their meaning. Some of the explanations provided show that the words were also used to refer to non-maritime activities. The French word “appareiller” means to set sail, but the Acadians also used it to mean getting ready to leave, but not necessarily by sea.1

Genviève Massignon has written about how many nautical terms were used in Acadian speech to refer to land-based contexts and situations. One example she provides is “amarrer” which means to moor or tie up a boat. The Acadians also used this word to refer to tethering a horse.2

12. L'Anse -des- Barnabe

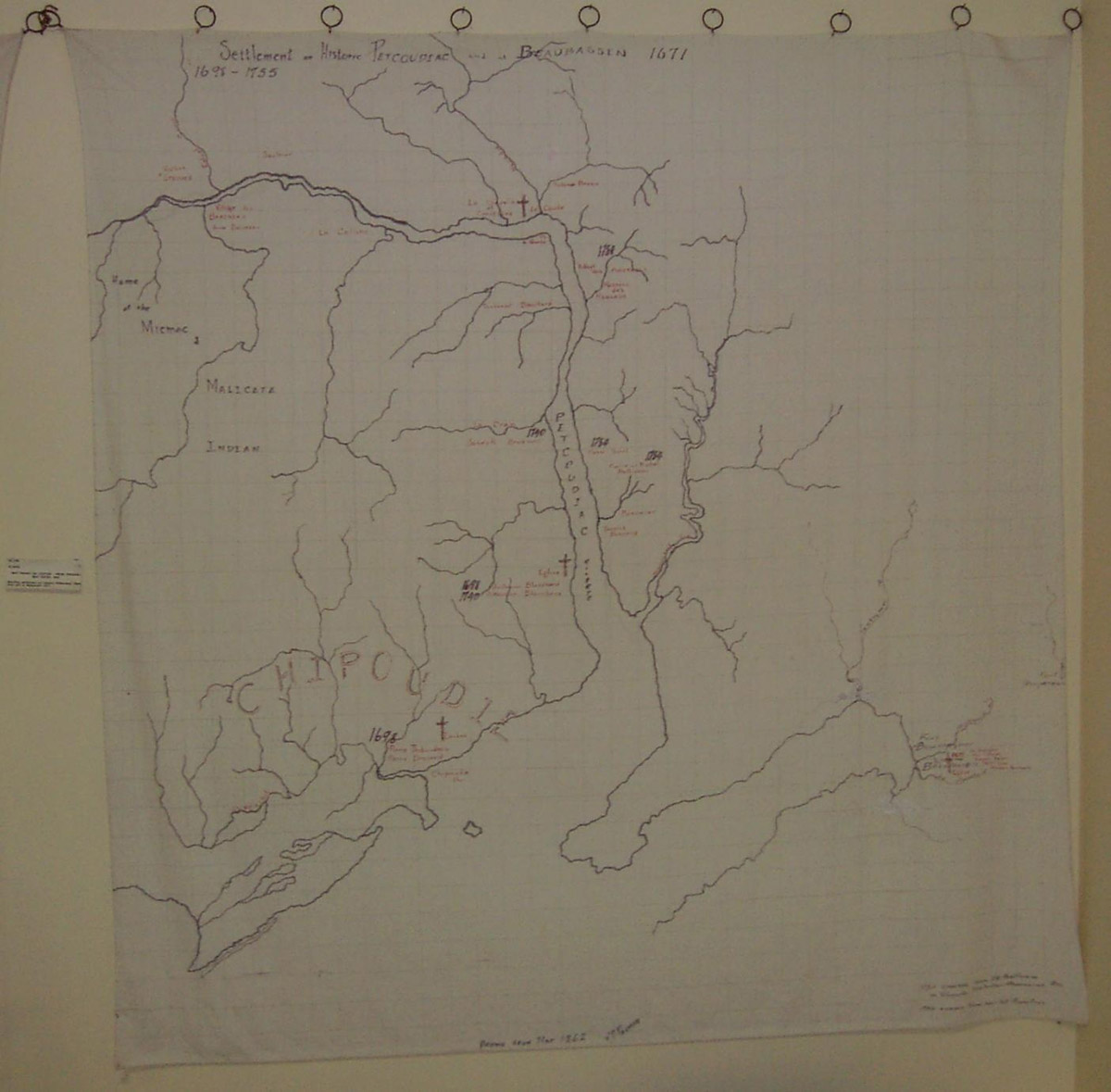

This photo is of a reproduction of a map showing Acadian settlements in Albert County from 1698-1755. The crosses on the map indicate the location of churches which demonstrates the centrality of religion in the lives of the Acadians.

In 1736, Jean Blanchard and his fiancée, Marie Rose Thibodeau, moved to the foot of the hill here. The two were later joined by Jean’s brother Paul, who married Marie Josephe Martin. Marie Josephe invited her family to the settlement, and the group was joined by Marie Josephe’s cousin Pierre, Pierre’s father René, and Pierre’s nephew, P’tit Pierre. P’tit Pierre’s three younger brothers, Charles, Claude, and Joseph also moved here.

Due to the number of Martins living here, the settlement was named L’Anse-des-Barnabé after the Martin family’s dit name of Barnabé.

* * *

A number of Acadian families, including some of those we have met on this tour, have what is called a dit name. A dit name is an alternate surname, usually derived from a personal or familial attribute. Dit is a form of the word dire which means “to say”; in this case, dit is loosely translated to mean “called.”

Dit names were developed for a variety of reasons, such as distinguishing between families with a common surname, particularly if more than one family with that surname lived near each other. It also allowed adopted children to keep both the surname of their birth and adopted families.1

The Martin family who settled on this spot differentiated themselves from other families with the same surname by adopting the dit name Barnabé which was the first name of Barnabé Martin who was most likely the first person of this Martin family to arrive in Acadia, though nothing is known of his parents.

Other dit names could be based on physical appearance (dit Leblond, dit Leroux), ancestral place of origin (dit Beauregard), or profession (dit Boucher). Some dit names are taken from a mother’s maiden name. A number of dit names were also related to military service; before identification numbers were used, early French military policy required a nom de guerre (“war name”) for all regular soldiers for identification purposes.

One way of writing a dit name is Claude Martin dit Barnabé, but the same man could be referred to as Claude Martin or Claude Barnabé. The dit name had the same legal recognition as the original surname which accounts for this interchangeability.

13. La Pres-des-trois-soeurs

This swatch of fabric was made by Marguerite Richard LaPierre circa 1800. It was woven in a style that is now thought to have been traditional among Acadians before the Grand Dérangement.

This spot was the second-to-last location in the area to be settled by Acadians. Joseph-Bernard Brun began diking this marsh in 1740.

Three women of the Thibeaudot family lived here with their husbands. Elisabeth Thibeaudot was married to a son of Charles Pellerin, while Marie Thibeaudot was married to Michel Girouard.

* * *

Providing clothing and other textiles for the family was usually the job of Acadian women. Most clothing was made of wool from the sheep that were kept. Wool was important because it provided warmth in the cold winters. The Acadians also grew flax which was used to make lighter summer clothes. Women used looms to weave the raw materials into cloth. All of this work was difficult, time-consuming, and done by hand so clothes were worn until they fell apart; the cloth was then repurposed into other textiles. Most clothing was red or black, with red cloth being used in a decorative way.1 Black dye was obtained from natural sources found in the nearby woods while red threads or fibres were taken from English-made cloth. Women unravelled this cloth then respun the red fibres for use in their own projects, like adding stripes to skirts.

Men were also involved in the making of clothing; they provided the raw materials used to make shoes. Hunting brought meat for food and furs for trading, but it also provided sealskin and moosehide which were made into shoes worn by everyone in the community.2 Special wooden shoes, known as sabots, were worn when working on boats or in the marshes.

A French travel writer who visited Acadian settlements in the early 18th century wrote about the clothing that he saw. Men wore collarless shirts with knee-length breeches and stockings. They usually wore hats—wool in the winter and straw in the summer. Women wore blouses, stockings, and ankle-length skirts bound with ribbons. Women also wore hooded capes covering their head and shoulders when outside. The writer noted that these were fashioned in a style that was popular in France fifty years earlier.3

Demonstrating their tenacity and perseverance, the Acadians who made their way to Louisiana after the Deportation adapted to making clothing from coton jaune or what is now known as Acadian brown cotton. Acadian women applied their skills in making cloth out of wool to this new type of fabric to provide blankets, bedding, and clothing for their families.

In the nineteenth century, gatherings in which many members of the community would come together to undertake large tasks were known as ‘bees.’ Acadians who returned to New Brunswick after the Deportation held fouleries which were fabric fulling bees. Fulling is the process of pressing pieces of woven wool fabric together to make them thicker. This thicker fabric would then be used to make warm and durable clothing. Fouleries often had a festive atmosphere. The men pressing the heavy pieces of fabric together would sing songs to coordinate their movements while women prepared a hearty meal for everyone to share. The evening would usually end with a dance.4

14. Le Village-des-Savoie

This photo shows the mosaic representing the Savoie family at the Acadian Memorial Meditation Garden. The plough on the family shield represents François Savoie, who was a farmer and the first of the Savoie family to settle in Acadia.

In 1699, Germain Savoie and his sons, together with Pierre Thibaudot, founded Chipoudie and dyked the large marsh here. Thibeaudot and his family settled at the foot of the mountain, while Savoie and his sons settled on the marsh between the mountains and the sea.

In 1704, the English raider Benjamin Church attacked and destroyed the settlements here, forcing everyone to return to Port-Royal. Germain Savoie’s sons, Jean and Paul, returned to the area in the early 1730s. They were joined by their nephews, François Richard, “Jani” Jean Savoie, and Jean-Baptiste Savoie. The eldest sons of Paul and Jean established themselves in neighbouring L'Anse-Des-Demoiselles.

* * *

It was rare for Acadians to pay each other for goods or services except in kind. Most of the economic relationships between Acadians were “barter-based, cooperative, or communal.”1

While the Acadians grew and produced much of what they needed to sustain themselves, there were some items that could only be gotten through trade with non-Acadians. Mattresses and coverlets filled with down were a noted Acadian product and feathers were often exported to Louisbourg. Families with an abundance of animals also traded livestock to Louisbourg in exchange for iron, French linens, rum, molasses, wine, and brandy.2 Most of the ceramics and china products in Acadian households came from France via Louisbourg. There were also economic relationships between the Acadians and the Mi’kmaq.

A noted trade existed between the Acadians and New England merchants. This economic relationship continued despite the British rules of mercantilism. Mercantilism is an economic system in which all colonies must trade with the home country exclusively. Raw materials were to be sent from New England to Britain and any manufactured goods that the colonists in New England wanted or needed had to be purchased from Britain. British colonies were not permitted to trade with each other, and certainly not with the Acadians who were perceived by the British to be French.

Nevertheless, these trade relationships were maintained. Acadians sold surplus grain to the English colonies and purchased goods such as tobacco, soap, and pipes.

15. Le Village-des-Thibaudot

This photo is of a grindstone used to mill wheat into flour. It is believed to be the original grindstone used by Pierre Thibodeau, who was also known as “Pierre the Miller,” at this location.

In 1689, Pierre Thibeaudot and his sons began diking the best location in the area, which became Chipoudie. Joseph Robinau de Villebon had granted Thibeaudot authority over Chipoudie, but this was contested in 1702. Claude-Sébastien de Villieu claimed that the Chipoudie, Petitcoudiac, and Memramkouk settlements had been granted to his father-in-law, the former Acadian governor Michel Le Neuf de la Vallière et de Beaubassin. De Villieu further claimed that Le Neuf had then granted those lands to de Villieu himself.

After the 1704 raids during which New Englanders had destroyed all of the settlements in the Trois-Rivières area, a number of Acadians, including the Thibeaudots, were forced to return to Port-Royal.

In the late 1720s, two of Pierre’s sons, P’tit Pierre and Charles, resettled and rebuilt Chipoudie. The sons of P’tit Pierre and the sons of Jean Breau built their homes here, locating them along what is now Tingley Brook.

A few years later, Abbe e’Entaige settled in the area, and a church, Notre-Dame-de-la-Visitation, was built where the dykes next to the enclosed meadow ended. By the late 1730s, the population of Chipoudie had doubled.

* * *

The way in which Pierre Thibodeau and de Villieu tried to resolve their dispute over land offers us a glimpse into how law and politics functioned in Acadian settlements. The case had to be referred to France so that the government there could decide who had the right to the lands in question. All of this land distribution occurred without the consent of the Mi'kmaq peoples, whose land the Acadians were occupying.

In this case, we again see that family ties could shape how land use was governed by the Acadians. The representative of the French king in Port-Royal, the centre of Acadia, was Mathieu de Goutin, a son-in-law of Pierre Thibeaudot. De Goutin sent a report to the King’s ministers explaining to them the improvements Thibeaudot had made to the land, including the dykes that had been created and the sawmill and gristmill that had been set up.

In 1703, the Council of State at Port-Royal issued a decree that the settlers of Chipoudie and Petitcoudiac could continue to live on the lands they had settled, but a later decision by the French Conseil d'État upheld de Villieu’s seigneurial rights to the territory. The settlers could continue to live and work on the lands they had claimed, but the rest of the area belonged to de Villieu. Thibeaudot never knew of this, however—he died at Port-Royal before the final decree was issued.

16. La Pree-des-Pitre

This is a photograph of the Wall of Names at the Acadian Memorial in St. Martinville, Louisiana. The Wall of Names lists approximately 3000 people who were identified as Acadian refugees in early Louisiana records. The Wall of Names includes members of the Pitre and Robichaud families.

In the early 1730s, Pierre Pitre and François Robichaud, who would later marry Pierre’s sister Angelique, moved their families to this spot and dyked a section of land along the Grand Ruisseau (now Sawmill Creek). Shortly afterwards, François passed away and Pierre’s father Claude moved to the settlement to help out. The Pitre family dyked another large section of marsh before Claude Pitre passed away in 1744 at the age of 75.

* * *

François Robichaud’s father and uncle are believed to have been passengers on the Pembroke, a ship that was meant to take more than 200 exiled Acadians to North Carolina during the Expulsion.

The Acadians on board revolted and seized control of the ship when it became separated from the rest of the fleet during a bad storm. They sailed for the Saint John River, an area that was still controlled by the French military.

The Acadians were discovered by an English ship that was disguised as a French one, with men dressed in French military uniforms and a flag in the French colours. They armed themselves and fired on the English ship. One Acadian was captured by the French, while eight English crew members were captured by the Acadians, who then burnt the boat to prevent it being used by the English again. Many of the passengers of the Pembroke travelled up the Saint John River, seeking refuge in the Acadian villages there.1

While the seizing of this ship may seem a small victory, for a group of people being forcibly removed from their culture, their homes, and their families it offered a moment of hope. Seemingly small moments of resistance remind us that even under extreme duress and oppression, the people of the past rose up and pushed back.

The story of the Pembroke is an important Acadian story and has become part of the rich tradition of Acadian storytelling; many of these stories come in the form of legends, folktales, and songs. Some of these stories and songs were brought to Acadie by the first French settlers in the area and were passed down through generations. Most Acadians were unable to read or write, so these important traditions were transmitted orally.

17. Le Village-des-Comeau

An imprint of an engraving by F.R. Schell, this image depicts cattle being herded along dykeland road. The image was originally published in the second volume of G.M. Grant's Picturesque Canada.

In the early 1720s, the sons of Pierre Comeau, with the understanding of their Thibeaudot brothers-in-law, chose settlement sites on the Chipoudie River to the west of the Grand-Ruisseau. They settled on a knoll next to meadows that were able to produce crops quickly. Joseph Comeau undertook the reclamation of the most demanding area, and his brothers Maurice and Ambroise helped. The brothers built new homes at the mouth of the ravine, and in the late 1740s, Joseph permitted his daughter Marguerite and her fiancé, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Levron, to build next to him.

* * *

The Acadians have always had a strong oral tradition and folklore has been passed from generation to generation and between members of small communities. This has allowed Acadians to maintain parts of their culture in spite of the Deportation.

Studying folklore can help us to learn about social histories and the values held by people in the past. Over 80 percent of Acadian folk songs are ones that were composed in France and brought over by some of the first French settlers in what would later be known as Acadia. Many of these songs were written during the Medieval period.1

Most of the themes found in Acadian legends and tales are related to religious beliefs. Stories featuring Purgatory, the devil, and priests are the most common. In some stories, people whose souls are in Purgatory are called back to earth in order to make amends for a wrongdoing they committed before they died, while in others priests use the powers invested in them to defeat the devil, fires, and sorcerers.2

Religion and folklore among the Acadians are linked through practices focused on seasons or celebrations as well. Quiet, solemn ceremonies were held in cemeteries to mark the beginning of nature’s dormant season in early November. The counterpoint to these ceremonies came with the rebirth of nature in May when outdoor altars would be covered in flowers.3

18. Le Pree-des-LaBauve

This is a photo of the Chipoudie Monument in Riverside-Albert taken at its unveiling in 2019. The committee formed to establish this monument was led by William Savoie and consisted of descendants of the other families who settled in the area. A group from the United States, all descendants of Pierre Thibeadau, travelled to attend the unveiling.

In 1741, Louis Labauve and Jean-Baptiste Levron chose to settle here, the only undeveloped area of the Grand-Prée. Homes were built at the entrance of a small stream leading to the marsh.

On September 1st, 1755, two English ships sailed up the river and soldiers set fire to the entire settlement.

* * *

If you have looked up any information about the Acadians on the internet, you probably encountered numerous websites focused on genealogy. Genealogy is critically important to the Acadians because of what happened during and after the Expulsion when the Acadians were sent to the Thirteen American Colonies, the Caribbean, England, and France. Some Acadians left these places to establish a new homeland in Louisiana.

Most Acadian settlements, like the ones we have encountered on this tour, were settled by kin groups and large, extended families lived close to each other. The Deportation changed this; families were split up into smaller groups intentionally.

There was some effort to keep younger children with their parents, but this was not necessarily done for adult children. Even in cases where many members of a family were deported to the same place, some of the American Colonies divided them. Brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents could be sent to different locations within the same colony.

Genealogy reconnects the families scattered by the Expulsion. Not everyone returned to New Brunswick or Nova Scotia when they were permitted to. Some stayed in the original Thirteen Colonies, and there is a thriving community of the descendants of Acadians—Cajuns—in Louisiana. Tracing family ties across the globe has helped reinforce and maintain the distinct Acadian culture and lifestyle that we see today.

Endnotes

1. La Pointe-Du-Coude

1. The Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq, Kekina’muek: Learning about the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia (Truro, NS: Eastern Woodland Print Communication, 2007), 1. https://native-land.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Mikmaq_Kekinamuek-Manual.pdf.

2. Les Anses de l'aval

1. Naomi Griffiths, The Contexts of Acadian History, 1686-1784 (Montréal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992), 47.

2. Naomi Griffths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748,” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 26.

4. LeCran

1. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 27-28.

2. John Knox, An Historical Journal of the Campaigns in North America for the Years 1757, 1758, 1759 and 1760, ed. A. G. Doughty, 3 vol. (Toronto, 1914-18), 105. Qtd in Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 28.

3. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 28.

5. La Pres-des-Dubois

1. Régis Brun, The Acadians Before 1755 (Global Heritage Press, 2012), 61.

2. Régis Brun, The Acadians Before 1755 (Global Heritage Press, 2012), 61

3. Naomi Griffiths and Mount Allison University, The Contexts of Acadian History, 1686-1784 (Montréal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992), 74.

6. Le Village-des-Blanchard

1. Ronald Labelle, “Offering New Lamps for Old Ones: The Study of Acadian Folklore Today,” in Teaching Maritime Studies, ed. Phillip A. Buckner (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986), 198.

2. Ronald Labelle, “Offering New Lamps for Old Ones: The Study of Acadian Folklore Today,” in Teaching Maritime Studies, ed. Phillip A. Buckner (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986), 198.

3. Georges Arsenault, Acadian Christmas Traditions (Acorn Press, 2007).

8. La Pree-Des Bertrand

1. Barbara Le Blanc, All Join Hands: A Guide to Teaching Traditional Acadian Dance in School (Halifax: Dance Nova Scotia, 2004), 1-1.

2. Percy A. Scholes, The Oxford Companion to Music, ed. John Owen Ward, 10th ed. (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), 125.

3. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Branle,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/art/branle.

9. L'Anse-des-LaRosette

1. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 30-31.

2. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 30.

10. La Pree-Des-Brun

1. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 28-29.

2. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 31.

11. L'Anse-DesDamoiselles

1. Naomi Griffiths, The Contexts of Acadian History, 1686-1784 (Montréal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992), 52.

2. Genviève Massignon, Les parlers français d'Acadie: Enquête linguistique (Paris: Librairie G. Klincksieck, 1962), 443.

12. L'Anse -des- Barnabe

1. Stephen White, Patronymes acadiens/Acadian Family Names (Moncton: Éditions d'Acadie, 1992).

13. La Pres-des-trois-soeurs

1. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 29.

2. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 30.

3. Sieur de Dièreville, Relation of the Voyage to Port Royal in Acadia or New France,

ed. J.C. Webster (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1933), 96.

4. “Acadia: Lifestyle in the Days of our Ancestors,” Village Historique Acadien Virtual Museum.

14. Le Village-des-Savoie

1. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 30.

2. Naomi Griffiths, “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 28.

16. La Pree-des-Pitre

1. Paul Delaney, <<La reconstitution d’un rôle des passengers du Pembroke>>. Les Cahiers de la Societe historique acadienne vol. 35, nos. 1 & 2 (2004): 4-75.

17. Le Village-des-Comeau

1. Georges Arsenault, “Folklore and Social History,” in Teaching Maritime Studies, ed. Phillip A. Buckner (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986), 184.

2. Ronald Labelle, “Offering New Lamps for Old Ones: The Study of Acadian Folklore Today,” in Teaching Maritime Studies, ed. Phillip A. Buckner (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986), 197-198.

3. Ronald Labelle, “Offering New Lamps for Old Ones: The Study of Acadian Folklore Today,” in Teaching Maritime Studies, ed. Phillip A. Buckner (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986), 198.

Bibliography

“Acadia: Lifestyle in the Days of our Ancestors,” Village Historique Acadien Virtual Museum.

Arsenault, Georges. “Folklore and Social History.” In Teaching Maritime Studies, edited by Phillip A. Buckner, 184-189. Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986.

———. Acadian Christmas Traditions. Charlottetown: Acorn Press, 2007.

Brun, Régis. The Acadians Before 1755. Milton, ON: Global Heritage Press, 2012.

The Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq. Kekina’muek: Learning about the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia. Truro, NS: Eastern Woodland Print Communication, 2007. https://native-land.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Mikmaq_Kekinamuek-Manual.pdf

Dièreville. Relation of the Voyage to Port Royal in Acadia or New France. Edited by J.C. Webster. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1933.

Delaney, Paul. <

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Branle.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, July 20, 1998. https://www.britannica.com/art/branle.

Griffths, Naomi. “The Golden Age: Acadian Life, 1713-1748.” Social History 17, no. 33 (1984): 21-34.

Griffiths, Naomi and Mount Allison University. The Contexts of Acadian History, 1686-1784. Montréal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1992.

Kennedy, Gregory. “Marshland Colonization in Acadia and Poitou during the 17th Century.” Acadiensis 42, no. 1 (2013): 37-66.

Knox, John. An Historical Journal of the Campaigns in North America for the Years 1757, 1758, 1759 and 1760. Edited by A. G. Doughty, 3 vol. Toronto, 1914-18.

Labelle, Ronald. “Offering New Lamps for Old Ones: The Study of Acadian Folklore Today.” In Teaching Maritime Studies, edited by Phillip A. Buckner, 196-205. Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1986.

Le Blanc, Barbara. All Join Hands: A Guide to Teaching Traditional Acadian Dance in School. Halifax: Dance Nova Scotia, 2004.

Massignon, Genviève. Les parlers français d'Acadie: Enquête linguistique. Paris: Librairie G. Klincksieck, 1962.

Scholes, Percy A. The Oxford Companion to Music. Edited by John Owen Ward, 10th ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Saint Croix Island International Historic Site General Management Plan: Environmental Impact Statement. 1998.

White, Stephen. Patronymes acadiens/Acadian Family Names. Moncton: Éditions d'Acadie, 1992.