Colonial Church & School Society

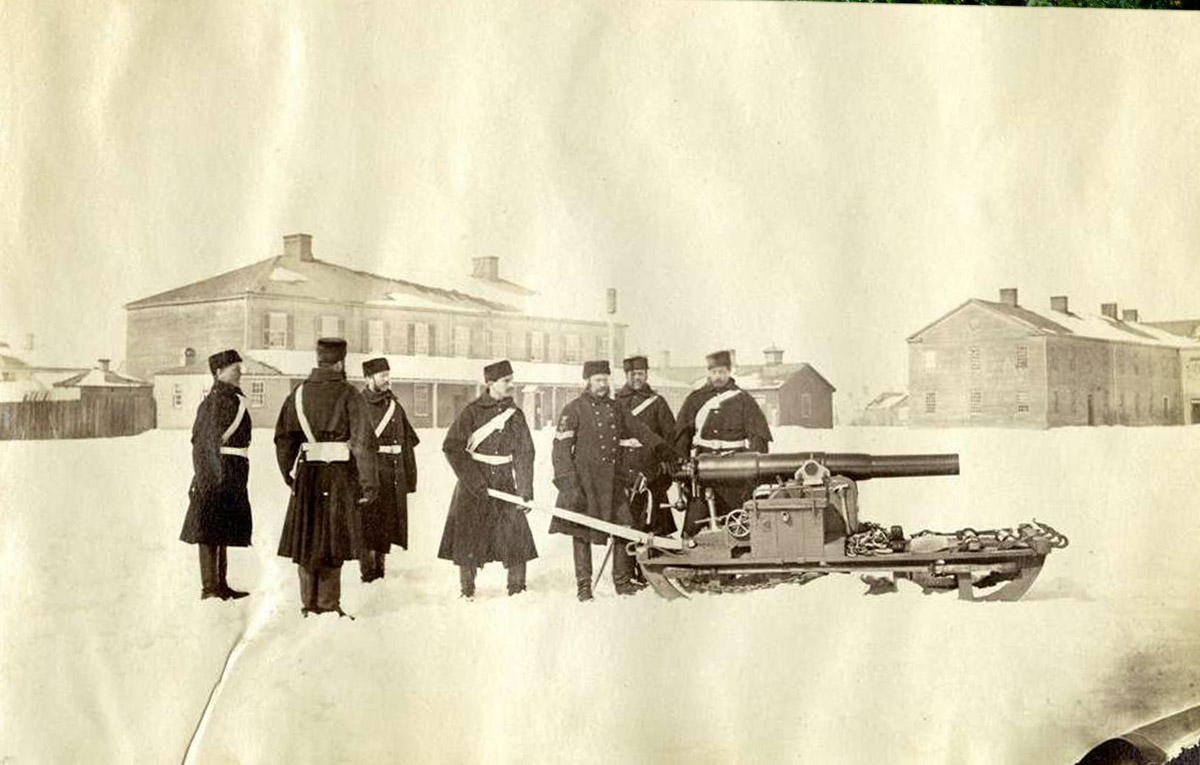

An artillery gun sleigh, drawn up in front of the British Army barracks in what is now Victoria Park.

Following the Rebellion of 1837, regiments of the British Army were posted to various places in the Canadas. In London, a base covering a large area was established on the north edge of town, part of which would later become Victoria Park. The barracks, which usually housed part of a regiment, were almost empty during the 1853-56 Crimean War and immediately thereafter.

It was during this time that the Colonial Church and School Society was offered part of the Royal Artillery barracks for use as a school. The Society had been organized to minister to settlers in far-flung reaches of the colonies. One section was set up to provide schooling to those in the colonies who had been freed by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and to the formerly enslaved who had escaped to Canada. They located their Canada West school in London, where the rapidly growing Black population had reached an estimated 350 by 1855. There was also support there from the Anglican clergy and laity. During this period, few Black children were attending the common schools because of the vociferous opposition to their presence from white parents. This prejudice often extended to the teaching staff.

The school was led by the Rev. M. M. Dillon, a member of the Society in England and a proponent of integrating the Society’s schools. He had volunteered to lead the mission to Canada West himself. Prominent white families impressed with the discipline and a religiously-infused curriculum also sent their children to the school. In June of 1855, Benjamin Drew, an American abolitionist then touring Canada West, found 175 students at the school, 50 of whom were Black. The total number of school-aged children in the Black community was 96 in 1862. Rev. Dillon left London in 1856 due to ill-health and, losing its driving force, the school closed two years later.

Not everyone supported the initiative. Mary Ann Shadd, editor of the Provincial Freeman newspaper in Chatham, called it misguided charity. She argued that Blacks, who paid taxes to support the public schools, should have equal access to them. However, it was very difficult to overcome the widespread white opposition to integrated schools. In fact, in 1863, the school board decided to build a separate school for Black students. This did not happen, possibly because of the decline in the Black population following the end of the Civil War.

Following the Rebellion of 1837, regiments of the British Army were posted to various places in the Canadas. In London, a base covering a large area was established on the north edge of town, part of which would later become Victoria Park. The barracks, which usually housed part of a regiment, were almost empty during the 1853-56 Crimean War and immediately thereafter.

It was during this time that the Colonial Church and School Society was offered part of the Royal Artillery barracks for use as a school. The Society had been organized to minister to settlers in far-flung reaches of the colonies. One section was set up to provide schooling to those in the colonies who had been freed by the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and to the formerly enslaved who had escaped to Canada. They located their Canada West school in London, where the rapidly growing Black population had reached an estimated 350 by 1855. There was also support there from the Anglican clergy and laity. During this period, few Black children were attending the common schools because of the vociferous opposition to their presence from white parents. This prejudice often extended to the teaching staff.

The school was led by the Rev. M. M. Dillon, a member of the Society in England and a proponent of integrating the Society’s schools. He had volunteered to lead the mission to Canada West himself. Prominent white families impressed with the discipline and a religiously-infused curriculum also sent their children to the school. In June of 1855, Benjamin Drew, an American abolitionist then touring Canada West, found 175 students at the school, 50 of whom were Black. The total number of school-aged children in the Black community was 96 in 1862. Rev. Dillon left London in 1856 due to ill-health and, losing its driving force, the school closed two years later.

Not everyone supported the initiative. Mary Ann Shadd, editor of the Provincial Freeman newspaper in Chatham, called it misguided charity. She argued that Blacks, who paid taxes to support the public schools, should have equal access to them. However, it was very difficult to overcome the widespread white opposition to integrated schools. In fact, in 1863, the school board decided to build a separate school for Black students. This did not happen, possibly because of the decline in the Black population following the end of the Civil War.