Driving Tour

Story of the South Okanagan

Driving From Peachland to Osoyoos

Lindy Marks

Welcome to the On This Spot driving tour of the South Okanagan.

This tour will take you from the Thompson Okanagan Visitor Centre on the Highway 97C connector just before the turn off to the South Okanagan, leading you all the way throughout the South Okanagan to the town of Osoyoos near the United States and Canadian border.

We will explore the history, geography, and ecology of this unique and rich region of the province.

Along the way, I will point out some of the fascinating and exciting things to do and see in the many towns we will pass through.

The tour is divided into eight segments, each one stretching between two towns and covering a different aspect of South Okanagan history.

A quick reminder, the use of handheld devices while driving is prohibited by law within Canada. Press play on this audio tour before you start driving and keep your eyes on the road.

1. Starting in Peachland

On this first segment of the tour, drive east on Highway 97C from the Visitor Information Centre for three minutes. Take the BC-97 S exit to the right as soon as possible and travel southwest on the Okanagan Highway until you reach the town of Peachland.

For this first tour segment, we will start at the beginning of human history in the South Okanagan, with the history of the Syilx Okanagan First Nations people. Long before the towns of the South Okanagan were here, long before the highway you drive on existed as even a dirt road, the Syilx People of the Okanagan Nation called this place home.

* * *

The Okanagan Nation has long thrived off of a relationship to the land and waters of their territory. According to the Okanagan Indian Band, the "Syilx Okanagan People have come from the land and animals themselves. Before humans were created, animal people lived on the land and gave up themselves along with their ways, beliefs, practices, and experiences for the people-to-be."For centuries, the Syilx People have lived sustainably off of the land, developing a wealth of knowledge about the environment and its cycles and seasons. Traditional forms of food harvesting include berry picking, the hunting of wild game, fishing, and the gathering of roots and other plants. Harvesting food goes beyond the need to eat and holds spiritual and ceremonial meaning, creating a bond to the land and demonstrating respect for all living things.

The Syilx People speak the nsyilxcən language, which is part of the Salish language family. This language is distinct from other Salish languages such as Spokan, Nlaka’pamux, and Secwepemc. It is spoken all across the Okanagan Nation's territory, though different dialects exist throughout the region. Currently, extensive efforts are being undergone to revitalise the nysilxcən language. Residential schools combined with other damaging aspects of colonization led to the decline of the language throughout the twentieth century. As part of national initiatives at First Nations' language revitalization, the Okanagan Nation Alliance is striving to promote language-learning and cultural resources. This includes the development of school curriculum, immersion schools, web-based tools, and language books. The work is being guided by the Elders in the community.

The arrival of Europeans in the South Okanagan in the early nineteenth century disrupted many of the traditional ways of life of the original inhabitants of this land. During the fur trade, new practices, tools and worldviews were introduced. European introduced diseases such as smallpox swept through Canada from coast to coast even before the beginning of the fur trade, with epidemics occurring in the Okanagan as early as 1775 and 1781.

Missionaries began to enter the Okanagan throughout the nineteenth century. The main mission community was formed near Kelowna by Father Pandosy in 1859. It was the first permanent European settlement in the Okanagan Valley. Churches and Residential Schools popped up throughout the Okanagan.When the fur trade began, the Syilx People largely participated through the selling and trading of horses.

The Okanagan was located along the route of the Fur Brigade Trail. Even though there were few of the small animals that fur traders prized, the region was a busy place during the years of the trade. The horse trade was a valuable contribution to the fur trading economy. The local First Nations also worked as horse wranglers for the traders occasionally.

As the fur trade declined and European settlement picked up speed, local relationships with the First Nations people shifted again. As Europeans acquired more and more land through pre-emption and sale from the government, First Nations were restricted to shrinking reserve lands. The creation of the United States/Canadian border in 1846 at the 49th parallel also disrupted traditional ways of life. The territory of the Okanagan Nation was cut in two, and traditional trade routes were stifled.

Today, the Okanagan Nation Alliance includes seven First Nations bands which inhabit the territory. This includes the Upper Nicola Band, the Okanagan Indian Band, the West Bank First Nation, the Penticton Indian Band, the Osoyoos Indian Band, the Lower Similkameen Indian Band, and the Colville Confederated Tribes.

In 1987, the Syilx People signed the Okanagan Nation Declaration, which states their sovereignty and right to traditional ways of life and land. The declaration reads:

“We are the unconquered aboriginal people of this land, our mother; The creator has given us our mother, to enjoy, to manage and to protect; we, the first inhabitants, have lived with our mother from time immemorial; our Okanagan governments have allowed us to share equally in the resources of our mother; we have never given up our rights to our mother, our mother’s resources, our governments and our religion; we will survive and continue to govern our mother and her resources for the good of all for all time.”

This driving tour takes place on the unceded, traditional territory of the Syilx People. Throughout the rest of the tour, we will continue to explore First Nations' history in various aspects. It is important to remember as we continue on in our drive throughout the region that we are travelling on this ancestral territory.

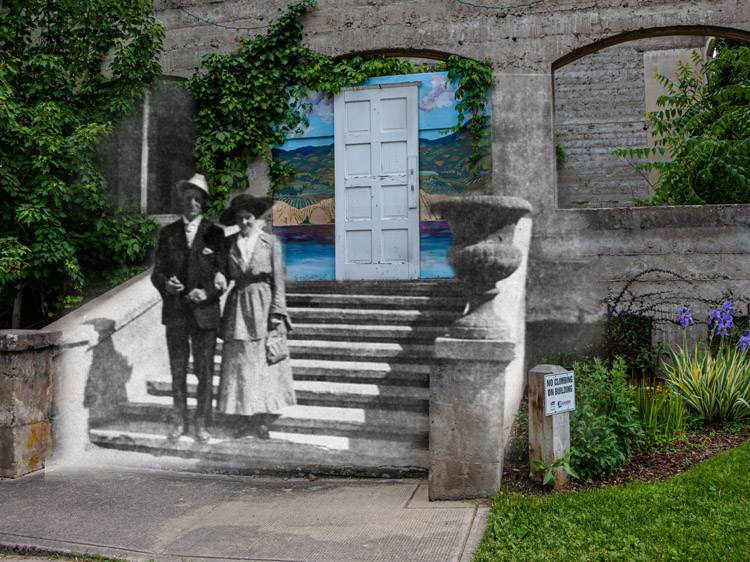

You are beginning to enter the outskirts of Peachland now. This small, lakeside town is known for its beaches, historic buildings, and of course peaches. The Peachland Historic school houses the Visitor Centre and Artisan Gift Store. The Peachland Art Gallery features new exhibits monthly and is home to one of the largest bat colonies in BC. Turn left at Princeton Avenue and take another left on Beach Avenue to enter the town proper. The Peachland Museum will be on your left, housed in the historic Baptist Church building. Here, you can dive deep into the history of the Baptist community in Peachland at our On This Spot story location. Or, visit the museum to check out the town's hist orical artifacts and a fully functional model train track.Spend some time in Peachland and explore our many then-and-now photo opportunities stretched throughout the downtown core. Read about the Fur Brigade Trail which passed through the area in the 1800s, or learn about Peachland's first school house. Our Peachland content is easily available on this app.

In the next segment of this tour, we will explore the geological and geographical history of the Okanagan Valley. We will also learn about the climate and ecosystems of the South Okanagan and touch upon the legends of the mythical Ogopogo.

2. Peachland to Summerland

From Peachland, we will drive to the town of Summerland on the western shores of the Okanagan Lake. From the Peachland Museum, travel southwest on Beach Avenue and turn left onto Highway 97. Stay on the highway for the next twenty kilometres, until you reach Summerland.

* * *

After the Eocene Epoch came the Oligocene Epoch, in which the Okanagan Fault developed. This fault line runs down the middle of the valley from north to south. It travels under Skaha Lake and zig zags through the southern part of the valley as it approaches Osoyoos. During the fault's development, rock material in the valley moved up to 100 kilometres to the west. The marks of this great change still remain in the valley today. On the western side, the rocks are mostly sedimentary and volcanic. In the east, on the other hand, the rocks tend to be either metamorphic or plutonic. This is caused by the fault's division of the valley.

The next major change which shaped the development of the Okanagan Valley was the Ice Age that began around 1.8 million years ago. Throughout this time, temperatures rose and then fell again, creating at least four distinct glacial periods and interglacial periods. The ice sheets would often cover everything but the highest peaks. The pressure and movement of the ice deepened the Okanagan Valley, carving away the land until the valley was below sea level.

The last ice sheets melted between 11,000 and 9,000 years ago. The melting ice created a great lake known to scientists as Lake Penticton. Massive melting blocks of ice formed a dam near Oliver. The water was trapped in the valley and rose to the tops of the cliffs. This lake extended north from the area of Oliver all the way to the Thompson River Valley hundreds of kilometres away. Gradually, the barriers holding the waters of Penticton Lake in place wore away and melted down. The water rushed free, flowing out of the valley. As it went, it dropped silt, sand, and boulders. Much of that silt is today used for agriculture and has helped to create the rich and abundant orchards and vineyards celebrated in the region today.The retreating waters scoured the bottom of the valley and left behind silt cliffs. Keep an eye out for these formations as we travel on. Silt cliffs are easily visible along the west side of Okanagan Lake between Summerland and Penticton in our next tour segment. You can also see the remnants of the ancient shore of Lake Penticton in the terraced benches which climb the valley walls and are today home to dozens of vineyards.

As for Lake Penticton itself, some water did remain behind, creating what is known today as the Okanagan Lake. If you look to your left, that's the lake beside you.It is over 350 square kilometres. It stretches from Penticton in the south all the way to Vernon in the north. At its deepest, the lake is 230 metres deep, but it has an average depth of only 70 metres. However, the lake would be much deeper if not for the vast quantities of sediment that the melting glaciers deposited at its bottom. In fact, if the sediment in the Okanagan Lake was removed down to the bedrock, the Okanagan Valley would be deeper than the Grand Canyon itself.

The Okanagan Lake holds more secrets than just the depths of its sediment, however. Legend has it that the mysterious lake-dwelling creature the Ogopogo lives in the lake. Its home is said to be Rattlesnake Island, just across the water from where you are currently driving. The Ogopogo is first recorded in the legends of the Syilx First Nations People of the Okanagan. Its original name is "N'ha-a-itk", which means "something in the water". According to Chief Byron Louis of the Okanagan Indian Band, its story has cultural and religious significance to the Syilx People. First Nation hunters believed the mythical beast lived in a cave below the lake near Rattlesnake Island. They would occasionally bring sacrifices of horses or other, smaller, animals to the monster. According to the stories, the animals would be pulled beneath the waves by something large, and the canoes would be flooded. The monster was believed to be a sea serpent with the head of a horse. The legend of N'ha-a-itk became popular among the white settlers of the Okanagan early on.

It is unclear where the name "Ogopogo" truly comes from. Some say it was derived from an anglicized version of N'ha-a-itk. Others believe it is a nonsense word made up by the band Cumberland and Strong. The band published a vaudeville song in 1924 in which the name appeared.

Wherever the name comes from, the legend of the Ogopogo has certainly captured the imaginations of visitors and residents alike. Even today, so-called "Legend Hunters" still search for it. Many sightings have been eagerly recorded. The creature is generally said to be between 30 and 70 feet long, with either two or three humps. It emerges from calm stretches of the lake as a mysterious, fast-moving swell which leaves behind a large wake.

As for its origins and identity, there are many theories. Some think it is a giant sturgeon fish. Others believe it is a dinosaur which escaped extinction due to the depths of the Okanagan Lake and the cooler temperatures of the water. Whatever the answer, both individuals and the local governments have embraced the legend of the Ogopogo. The BC Attorney General declared the Ogopogo an endangered species under the Fisheries Act. In the 1990s, the creature appeared on Canadian stamps. In 1983, the Okanagan/Similkameen Tourist Association offered a $1 million reward for a proper photograph of the Ogopogo.

Largely, the legend of the Ogopogo has been used as a tourist draw. The monster now appears as plushie toys in gift shops and statues in local parks. It is sold on t-shirts, hats, and mugs and decorates billboards and business logos. This "Disneyfication" of the legend has not been without controversy, however.

Since 1956, the City of Vernon has held the copyright for the Ogopogo. It has been in complete control of who uses the name, story, and image, and for what. Recently, this has raised concerns over cultural appropriation. The Ogopogo or, more rightly, the N'ha-a-itk, is a legend of cultural and religious significance to the Syilx People, after all. In March of 2021, therefore, the City of Vernon voted to give this copyright to the Syilx Nation instead.

There are more than just mythical creatures living in the Okanagan Valley, of course. The climate and ecosystems of the South Okanagan are unique in British Columbia and include an astounding amount of biodiversity. Around 190 species of birds breed in the South Okanagan. The desert grasslands are home to sagebrush, cacti, rattlesnakes, and groves of ponderosa pine trees.

In fact, the Okanagan Valley as a whole is home to more species of plants and animals than most areas of Canada. This is largely due to the unique climate of the area, which lies in a rain shadow created by the Coast and Cascade Mountains. The climate is hot, sunny, and dry, with about 2,000 hours of sunlight every year. The South Okanagan only receives about 300 millimetres of precipitation a year. This allows the desert ecosystems to thrive.Nowadays, however, this ecosystem is endangered.

Agriculture has transformed the sensitive habitats of the South Okanagan into lush farm land through extensive irrigation. The original grassland ecosystem is listed as "one of the four most endangered ecosystems in our country." Like glaciers or the movements of fault lines, humans have transformed the Okanagan Valley in major ways. While we haven't created mountains or drained mega-lakes, we have changed the ways in which water flows across the land.

You are now approaching the town of Summerland. This town is split into two distinct neighbourhoods. Originally, Summerland's townsite formed on the shores of the Okanagan Lake. It soon moved inland, to West Summerland.

To learn the story of Summerland's development, turn towards the water and towards our On This Spot story location "Summerland's Early Days". Turn left on Rosedale Avenue and then take a right onto Biagioni Avenue. From there, turn left onto Peach Orchard Road and travel towards the water. There is a campground along this road for those wishing to stay awhile. When you reach Lakeshore Drive, take another right. You can park anywhere along here at one of Summerland's many beaches.

Summerland is full of interesting history and things to do. Go hiking on Giant's Head. Or, learn the history of agricultural science at the Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre with the On This Spot story location "The Science of Agriculture". For an authentic South Okanagan experience, head to the Kettle Valley Steam Railway Historic Site. There, you can ride the last remaining section of the Kettle Valley Railway and cross over the Trout Creek Trestle. Explore the history of the KVR with our story location "The Coming of the Railway" and visit our many historical photo opportunities throughout town.

Our next tour segment dives into the history of the first Europeans to arrive in the South Okanagan. It will cover the history of the fur trade in the region, along with the placer and hard-rock mining which came after it. It will also delve into the stories of the early cattle kings who owned much of the South Okanagan in the late nineteenth century.

3. Summerland to Peachland

We will leave Summerland behind and proceed to the bustling city of Penticton, the largest community on our tour, which is nestled between the Okanagan and Skaha Lakes. It is one of only two cities in the world situated between two lakes. The other is Interlaken in Switzerland.

From the Summerland waterfront, head southwest on Lakeshore Drive until you reach Highway 97. Make a left turn here and remain on the highway for the next twelve kilometres. Then, cross the Okanagan River canal and enter the City of Penticton.

In this segment of our South Okanagan tour, we will learn about the first Europeans to arrive in the Okanagan Valley and the gradual beginning of European settlement. We will explore the story of the Fur Brigade Trail and then journey into the world of mining and prospecting that followed it. We will also learn about the early cattle ranchers who settled in the South Okanagan.We'll dive into the lives of the first European settlers to make their permanent homes in this region.

* * *

The Fur Brigade Trail was in use regularly by fur traders for twenty years. It was first established around 1826. It did not lose its popularity until after the official establishment of the Canadian/American border in 1846. This new border cut off trade to the Columbia River and led to the establishment of new, all-Canadian routes.

While the trail was in use, fur brigades consisting of between 200 and 300 horses frequently travelled through the Okanagan Valley. Horses would usually be laden down with two bundles of around 84 pounds each filled with furs and supplies for the journey.

They could comfortably travel twenty miles, or 32 kilometres, a day with this burden.Camping spots were established along the trail at this interval or slightly farther. This way, traders could reach a safe spot to spend each night without too much difficulty. The trail kept largely to the open country on the sides of the valley. Here, there was sufficient space for grazing animals, and the terrain was not too rough on the feet of unshod horses.

The trail ran along the west side of Osoyoos Lake in the south, then travelled through Myers Flat and passed by White Lake. It then wound through the Marron Valley and crossed the area where Green Mountain Road would later run, west of the town of Kaleden. Keeping to the west, it ran along Shingle Creek to Trout Creek, near Summerland and where you currently drive. Then, it descended to the shores of the Okanagan Lake where Peachland now sits. From there, it ran north to Kamloops along much of the same route that Highway 97 now takes.

After the Oregon Settlement in 1846, the border cut off the trail. The last fur trade brigade travelled down it the next year. The fur trade gradually declined throughout the Okanagan and the rest of the British Columbian interior. It was replaced by a new brand of resource frenzy: gold mining.

The Okanagan Valley missed most of the early gold craze that took over other areas of British Columbia. Yet the gold rush still had an indelible effect on the region, as nearby mines brought people through the area. Gold was discovered at Rock Creek, to the east of the Okanagan, in 1860. A year later, it was discovered at Blackfoot, ten kilometres north of Princeton. These mines brought travellers to the Okanagan Valley. The mining populations also often relied on resources like cattle that were beginning to be established here.

Mining at Rock Creek lasted less than two years, but this wasn't the end of mining in the South Okanagan. In the 1890s, there was a resurgence of mining in the region with the development of hard-rock mining technologies.

Between 1885 and the start of the 1900s, the Camp Hewitt Mining and Development Company prospected for gold. They prospected between Trepanier Creek, which you drove past earlier near Peachland, and Deep Creek near present-day Kelowna. Also in Peachland, real estate developer J. M Robinson had the ownership of several mining claims. He established the Kathleen Mine near Peachland, though it made him little money.

Hard-rock mining was far more expensive than the placer mining which had come before it. In placer mining, gravel is sifted for pieces of gold. Hard-rock, or lode mining, involves digging the gold from the rocks themselves. Investments had to be made into acquiring equipment and machinery and paying the wages of a larger staff of workers. In the South Okanagan, the capital for all of this generally came from the United States or from England. Local entrepreneurs simply did not have the finances.

In one small community, however, mining boomed—for a time. Near where the present-day community of Oliver sits, the town of Fairview bustled throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s. The first claim was made in 1887. The community took off after that. Some estimates place Fairview's population during its peak years at over 1,000. Fairview was the largest settlement in BC's interior during the time.It had hotels, shops, and profitable mining ventures.

Yet as with most mining communities in British Columbia, dazzling success was soon followed by a downfall. Mines ran out of gold, and by 1907, less than 150 people lived in Fairview. It soon vanished from the landscape. Today, a grassy field sits where the town used to. The only thing which remains of the community is its namesake: a fair view across the South Okanagan.

All of this mining in the region and in nearby regions required fuel to keep miners going. One such source was beef from the cattle ranches which developed throughout the South Okanagan during this time period. Cattle ranching was the first successful economic driver in the South Okanagan that encouraged the permanent settlement of Europeans. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the "who's who" list of the region would largely have comprised ranchers.

The land on which you are currently driving was owned almost solely by one man: Thomas Ellis, a rancher who became known as the "Cattle King of the Okanagan." Ellis first arrived in the South Okanagan in 1865 with his companion Andrew McFarleane. Together, they acquired a tract of land between the Okanagan and Skaha lakes, where Penticton now sits.Ellis bought his first seven heifers from a man who was unable to pay the customs duty at the United States/Canada border in Osoyoos. His career officially began.

While McFarleane soon moved on, Ellis remained in the area where Penticton now sits. He built himself a cattle empire. As soon as new land had been surveyed and became available, Ellis swooped down and bought it. And for a man of reasonable and growing wealth, this was not difficult. Land went for as little as $1 an acre. By 1885, Ellis was the largest landowner in the South Okanagan. He owned 30,000 acres of land around Penticton and in the surrounding region. His cattle herd had 3,750 head of cattle. Ellis's monopoly on the land and resources was such that other, smaller farmers simply did not have a chance to become established. Would-be settlers actually petitioned the government to open up the area around Trout Creek, in Summerland, to pre-emptions only. This would prevent Ellis from swooping in and buying that land too. Potential owners would have to live and build on the land in order to claim its title.

In the south, the resident cattle king was John Carmichael Haynes of Osoyoos. Haynes came to the Okanagan in the 1860s. He was originally Gold Commissioner and later the Customs Collector at the border station in Osoyoos. He acquired massive amounts of land near Osoyoos and began to build up his own herd of cattle. His job as customs collector worked out very conveniently for him.Many of his cattle came from herds attempting to cross the border. Haynes would cheaply buy from the drovers any animals that looked too weak to continue their journey to the goldfields of the interior. In this way, he built up his herd while not expending too many of his own resources.

By the time he died, Haynes owned nearly 21,000 acres of land. After his death, his property was purchased by Tom Ellis of Penticton. The land monopoly in the region only grew tighter. The stranglehold held by men such as Ellis and Haynes on the land in the South Okanagan did not just prevent other settlers from establishing themselves in the area. It also limited the local First Nations populations to their shrinking reserve lands. These were often located far from water sources and ideal growing conditions.

Yet this land monopoly did not last. Ellis and his family retired in 1905 and moved to Victoria. Their land holdings were purchased largely by the South Okanagan Land Company. This company then undertook the task of laying out a townsite on the banks of the Okanagan Lake. The town of Penticton was born.

You should now be approaching this town. After you cross the Okanagan River Canal, turn left on Westminster Avenue to explore Penticton. This city has a vibrant culture, long sandy beaches, and a wealth of historical landmarks and stories. A good place to start your explorations of the town is the Okanagan Lake waterfront. Travel on Westminster Avenue until you reach Power Street and make a left turn there. This will take you to Penticton's famous beachfront, where you can park and enjoy the sun and water.

Notable landmarks along this stretch of beach include the Heritage Park to the far west where you can visit the SS Sicamous museum. Learn all about the history of steamships and rail transportation in the South Okanagan at the On This Spot story location "By Waves and Rail." The Peach concession stand to the east is a familiar landmark to most visitors of Penticton. Nearby Main Street is a great place to go for a walk and soak in the culture of the city. Learn about the city's annual events with our Story Location "Penticton's Event Culture". Witness how the city has changed with our then-and-now photo sets. Our Story Location "From Fruit to Wine: An Evolution" is also available on our app to answer any questions you might have about the history of Penticton's fruit industry.

Our next segment of the tour dives into the South Okanagan's military history. We will explore the stories of those who fought and died in the First and Second World Wars and delve into the stories of those who remained behind. We will also learn the fascinating history of Commando Bay, a top secret training facility that was located near Naramata.

4. Penticton to Naramata

We are going to take a detour out of Penticton and along the east side of Okanagan Lake to the scenic and historic town of Naramata. The drive will take approximately twenty minutes one way and pass through a wealth of orchards and vineyards. The Naramata Bench is known for its wineries, vineyards and orchards paired with iconic lakeside views.The village of Naramata is rich with agricultural history and home to the 115-year old heritage, Naramata Inn.

On Penticton's Lakeshore Drive, travel east to Front Street. Turn left on Front Street, and at the traffic circle, take the second exit onto Vancouver Avenue. This street will turn into Lower Bench Road as it leaves Penticton behind. When you reach Tupper Avenue, turn right until you hit Middle Bench Road. Turn left here and continue north through the surrounding vineyards. Middle Bench Road turns into Munson Avenue, which in turn becomes Upper Bench North and then McMillian Avenue. Make a slight left onto Naramata Road and continue on this road for nearly nine kilometres. Enjoy the beautiful South Okanagan scenery as you drive.

You may also want to stop at one of the dozens of wineries along the way. As we drive towards Naramata, we will look at the military history of the South Okanagan. We will explore the stories of the Okanagan residents who served in the World Wars, and the stories of those who remained behind to support the homefront. We will also learn the fascinating story of Force 136, a group of Chinese-Canadians who were trained in subterfuge and guerilla warfare at a secret training camp just north of Naramata.

* * *

The town of Peachland suffered the greatest per capita loss of any community in Canada during the First World War. When the war broke out, this small village had a population of only 300. Despite this, sixty men enlisted. Seventeen never returned. In terms of modern population, this would be the equivalent of 290 of Peachland's 5,400 citizens dying during a war.

Many of the Peachland men who enlisted were single and recent immigrants from Britain. For them, patriotism was close to heart. Among the dead were two brothers, Donald Alexander Seaton and Archibald Fleming Seaton. The older boy, Donald, was killed at the age of 21 in 1916, in France. His younger brother Archibald stayed at home for the first two years of the war. When the news of his brother's death reached him, he too enlisted. Later, his family said that he was motivated by a desire to avenge his fallen brother. But he too died in 1918, this time of measles and diphtheria.

Another name now engraved on the Peachland cenotaph is William Menzies Dryden, who was killed at Vimy Ridge in 1917. William was a student when the war broke out, and was only twenty when he died. He was born in Alva, Scotland, but lived in Peachland with his mother, father, and sister.

In Penticton, dozens of men fell in the First and Second World Wars. Leonard Victor Adams also died at Vimy Ridge. Leonard enlisted in Kamloops in 1916 at the age of twenty-one. He was a fruit grower in Penticton and the only son of Mr. and Mrs. A. Adams.

Roderick Charlton Bird of Penticton also fell at Vimy Ridge in 1917. While his military record states that he was born in 1897, census records show that this was a lie. Roderick was born in 1899: he was just seventeen at the time of his death. He enlisted in the army at just fifteen or sixteen. He was working as a bank clerk when the war broke out, but joined the army in September of 1915. He had previously been part of the militia group the Rocky Mountain Rangers for a year. During a March attack on Vimy Ridge which Roderick took part in, 83 Canadians were killed and another 144 wounded or missing. Roderick was one of these casualties.

These stories provide only a small snapshot of the South Okanagan residents who risked their lives in the World Wars. There were dozens of others: dozens who left family behind, dozens who fell on foreign battlefields far from home. Hundreds more returned home from the war with lifelong who returned injured and traumatized. The Second World War had smaller casualty numbers across Canada, yet the effects were often just as traumatizing. Communities were ripped apart and lives were lost.

In the Second World War, Dunrobin's Bay, north of Naramata along the shores of the Okanagan Lake, served as a Special Operations Executive training camp. The bay, which came to be known as "Commando Bay", was accessible only by boat, perfect for more secretive operations. It was operated by the British Special Operations Executive, the forerunners of MI6, with the goal of training agents in subterfuge, sabotage, and guerilla warfare tactics.

The camp operated under immense secrecy. It is likely that few residents of the South Okanagan were even aware of the training operation in their midst. For twenty years after the war, the history of the camp remained a secret. There are still few military documents available to share the story of this operation.

The camp trained thirteen Chinese-Canadian volunteers, each specially selected for the dangerous tasks ahead of them. They were trained for Operation Oblivion, which hoped to infiltrate enemy lines in Japanese-occupied territories in Southeast Asia. Between May and September of 1944, these men studied the arts of sabotage and subversion. They trained in unarmed combat, small arms, explosives, wireless technology, and guerrilla warfare.

After their training in the Okanagan was up, Force 136 headed to Australia for further training. There, they learned parachute-jumping, the use of small boats, and other skills which would be relevant to their various missions. Members of this force later parachuted into the interior of Borneo. There, they worked from the inside to destabilize Japanese forces. Others served in India, Ceylon, and Malaya. Four were awarded military medals for their bravery in action.

The Commando Bay training operation was an incredible example of Chinese-Canadian military service. At the time of the Second World War, Chinese Canadians could not yet vote in Canada. They were denied full citizenship and faced racism on a daily basis. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 prohibited most forms of immigration to Canada.

Chinese-Canadians were barred from certain professions such as law and medicine. Until 1944, they were banned from serving in the Canadian military. This only changed when Canada and China joined forces in the war to oppose Japan.

Yet despite all of this, 25 Chinese-Canadians still volunteered for Operation Oblivion, which was sometimes referred to as a "suicide mission". Thirteen were chosen. Most were from British Columbia. Many were descendants of those who had worked to build the province's railways for little pay and with extremely dangerous working conditions.

After the Second World War was over, a new battle began for many of these Chinese-Canadians, this time on home soil. The members of Force 136, along with other Chinese-Canadian war veterans, fought against racism in Canada. Even after their service in the war, the Canadian Government did not give them the right to vote. It was not until 1947 that they were granted this right federally and were able work in the professions of their choice.

Many of the members of Force 136 went on to become community leaders in the fight for their rights. Douglas Jung became the first Chinese-Canadian Member of Parliament. Roy Mah was a labour organizer and newspaper editor.

Today, little remains in Commando Bay to share its fascinating history. All evidence of the training camp was stripped away when the operation was completed. The bay is still nearly inaccessible, best reached by kayak or other boat. A plaque on location was installed in 1988 to commemorate the bravery of Force 136.

It was not just those who served overseas that held the war efforts up. In both the First and Second World Wars, the efforts on the homefront were of crucial importance. This was true all across Canada, but held special weight in the Okanagan. The farming community here was crucial to supporting the troops overseas with food and supplies. Not only that, but Canada fed not just its own citizens but those of many other countries. Its contributions of food to Britain during the start of the First World War propped that country up when its own resources began to grow scarce.

Not all the men of the region could enlist in the wars: the manpower was needed in farming. Not even the women, who rose to the task of taking on most of the jobs that were then traditionally male, could successfully run all of the farms on their own. The job was simply too big. They were already focused on raising children, supporting the Red Cross, and keeping their communities running. They had taken on many then-male-centric jobs like firefighting, shopkeeping, factory work, and canning.

In the First World War, more than 22% of the farming workforce in the Okanagan enlisted in the war at its beginning. Yet the farms were pressed to produce more than ever before. They had entire armies to feed. Reducing production to meet the shortage of workers was simply not an option. One solution to this dilemma was the national initiative known as "Soldiers of the Soil". This program encouraged boys who were too young to enlist in the military to instead join the agricultural efforts.

In British Columbia, 1,671 boys joined this program. Of those, 200 were from the Okanagan Valley. They helped farmers cope with the strain of running their farms with few workers. Boys from urban areas would often work on farms in exchange for room and board from the farmers and a small amount of spending money. High school students who joined the program were exempt from exams and classes as well.

In the beginning of the First World War, Prime Minister Robert Borden had promised Canadian farmers that farmers in their early late teens and early twenties would be exempt from conscription. Their services were needed on their farms instead. However, he later ended this protection in April of 1918. Farmers who needed to remain home to look after agricultural production now had to apply for an exemption through a special tribunal. Not all of these exemptions were granted. The desperation of the overworked farmers increased. Programs like the Soldiers of the Soil eased this burden.

In the Second World War, similar problems occurred as the labour force again disappeared overseas. Farming in Canada was crucial to supporting the Canadian population, especially as the fighting in Europe disrupted key supply lines. At the time, the country received most of its seeds from places like the Netherlands and France. The war made receiving these seeds nearly impossible, so farmers in the Okanagan and across the country stepped up instead.

In Oliver, John and Esther Thorp joined a special farming program run through the BC Seed Cooperative. This program's goal was to produce seeds for the country's agricultural supply. Crops such as melons, onions, and lettuce were grown in Oliver until they turned to seed. These seeds were then dried. Some supported Canadian farmers. Some were shipped overseas to help the farmers in Europe survive the strains of war.

The war efforts on the home front were varied and important. The South Okanagan's farmers provide invaluable crops to both Canada's armies and citizens. Additionally, many of the local organizations worked to support those overseas. Branches of the Red Cross formed across the South Okanagan. The Red Cross ran fundraising efforts for the war, collected medical supplies, rolled bandages, and sent care packages to the soldiers who had gone to Europe. Local Women's Institutes and other organizations knitted and sewed to create warm garments for the soldiers.

Both the First and Second World Wars tested the strength, kindness, and ingenuity of the communities in the South Okanagan. For both those at home and those fighting abroad, these times of war were traumatic and difficult, shaping both their lives and their futures.

You are approaching the village of Naramata. Make a left onto Old Main Road to enter the town and explore the lakefront. As you make your way into the town, Manitou Park will be on your left. Park here to enjoy the beach and learn about Naramata's early history with our Story Location "The Story of JM. Robinson." We also have a collection of then-and-now photo opportunities in Naramata. There are two other Story Locations which dive into the history of the Kettle Valley Railway and the orchards and vineyards on the Naramata Agricultural Bench. Visit the Naramata Inn, take a wine tour, or go for a swim in the lake. Then, when you are ready, travel back the way you came along Naramata Road back to Penticton, where you can continue the journey southwards from there.

In the next segment of the tour, we will dive into the history of steamships and lake transportation in the South Okanagan. We will look at how these boats transformed the Okanagan and learn about the coming of the Kettle Valley Railway to the region in the 1910s.

5. Penticton to Kaleden

After our scenic trip to Naramata, we will continue our journey south from Penticton to the small town of Kaleden. This town is known best for its ruined hotel and historic general store.

When you re-enter Penticton, travel west on Lakeshore Drive and turn left onto Power Street. When you reach the roundabout, take the second exit onto Vees Drive and from here, rejoin Highway 97. Travel on the highway along the western shores of Skaha Lake for another twelve kilometres.

In this segment of the tour, we will learn about the history of transportation in the South Okanagan, from the early rowboats that plied the lakes to the luxury steamships. We will also look at the development of the Kettle Valley Railway and how this transformed the Okanagan.

* * *

Travelling across the water was far easier and, for the most part, more reliable than land travel. The first commercial boat to carry freight and passengers in the South Okanagan went into business early on, in 1883. Rather than the luxury steamers which would one day dominate the waters, this boat was a far simpler affair. It was a rowboat called the Ruth Shorts, captained by T.D.Shorts. Captain Shorts later took to the waters with the steamboat the Mary Victoria Greenhow in 1886. This new boat could carry five passengers and five tons of freight, an improvement after the much smaller rowboat.

This was the first steamship on Okanagan Lake, and was a sign of things to come. Shorts went on to captain increasingly sophisticated vessels. His next steamships were the Jubilee and the Penticton. The Penticton was, able to carry up to 25 passengers.

On Lake Skaha, which you will be able to see to the left of Highway 97 on the way to Kaleden, steamboat traffic was also beginning to develop. Okanagan Falls founder W.J.Snodgrass first launched the SS Jessie in 1894.

The boat was named for his second daughter Jessie but burned at the dock only four years after its construction. Snodgrass subsequently launched the SS Greenwood and the SS Maud Moore. The Greenwood ran until 1903 and the Maud Moore until 1905. After 1905, Skaha Lake grew quiet, with little commercial lake traffic until 1922.

On Okanagan Lake, Captain Shorts did not go without competition for long. The formidable Canadian Pacific Railway company soon entered the scene. The Shuswap & Okanagan Railway line reached Okanagan Landing in the north, near Vernon, in 1892. The Canadian Pacific Railway realized the potential of tapping into the South Okanagan market with a steamship on the Okanagan Lake. The vessel would run from Penticton in the south to Okanagan Landing in the north. This would allow passengers from almost anywhere along the lakeshore to reach the rest of the province by waves and rail. They could transfer at Okanagan Landing onto the rail line. Even better for the company, this rail line connected to the CPR line at Sicamous, guaranteeing the company a new source of rail traffic.

The CPR steamship the SS Aberdeen launched on Okanagan Lake in 1893. The vessel was 146 feet long, a far cry from a rowboat. It had a cargo-deck capacity of around 200 tonnes and was built for luxury. There were eleven state room cabins, a ladies' saloon, a smoking deck, and a dining room.

This new CPR boat changed everything. It was far more reliable than the vessels of Captain Shorts, with more space for both people and cargo. In many ways, it had the same transformative effect on the region that a branch line of the railway would have had. Farmers could use the vessel to get their produce to larger markets. The mail could arrive with far more reliability and in less time. Residents suddenly had access to the entire province of BC. Their remoteness, while still great, decreased.

The steamship route was not without difficulties, of course. Most communities lacked any form of proper dock. The Aberdeen had to simply pull up as close to shore as she could. Gangplanks were then lowered, and the passengers tiptoed across these narrow bridges and onto the boat. The vessel stopped at eight communities, but it would stop at more if a potential passenger stood on the shore and waved a lantern or flag at it.

In the winters, ice on the lake was often a major problem. Nowadays, even a thin crust of ice on the lake is a rare occurrence. But at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Okanagan Lake would sometimes freeze so solid that cars and horse-drawn carts could drive across it. During these times, the boats struggled to break through the ice and reach their destinations.

The winter of 1915 and 1916 was particularly bad for the CPR steamships. Strong winds and thick layers of ice stopped the vessels from reaching Penticton and Naramata in January of that year. Even the tugboats could not push through the ice or make a path for the steamships. It took eight weeks to reopen the route to the southern end of the lake.

In a blizzard, the powerful thrum and crack of a steamship breaking through the ice was sometimes the only indication that it was approaching. The weight of the ship crushed the ice beneath it and then pushed it to the sides.Winters were a strain on the steamships. The paint was scratched and the paddlewheels had to be constantly de-iced. Yet for the most part, the vessels completed their journeys successfully. The towns up and down the Okanagan Lake came to rely on them.

The SS Aberdeen ran alone on the lake until 1907, when the steamship the SS Okanagan joined it. These two vessels, both owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway, were finally able to provide daily trips across the lake. Previously, the Aberdeen had run three times a week.

Then, in 1914, the Okanagan Lake gained a new vessel: the SS Sicamous. This new boat was the height of steamship luxury. It was larger than either the Aberdeen or the Okanagan and could carry up to 500 people. It had five floors, and a total of 30 rooms for overnight guests. Not only that, but it was furnished and arranged in magnificent style. The cost of the boat was reported at $180,000. The furnishings themselves cost an additional $14,000. There was even a piano on board, and the dining room was fit for a feast or a party.

The food on the SS Sicamous was of five-star quality, cooked fresh on board with local ingredients. The vessel also had both hot running water and electric lights. These innovations had not yet reached many of the farmhouses on the surrounding shores. Passengers could even pay fifty cents for a hot bath while on-board.

As one passenger, Mary Orr, said when recalling the steamship, "...the SS Sicamous provided a stateliness, a dignity, a peacefulness, a nobility, to our lives that many of us will never forget."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the luxuriousness of this new boat, it was not used solely for transportation purposes. Pleasure excursions were one of the services it provided. Moonlight cruises, dances, and dinners were all popular on the Sicamous. Local service clubs and church groups held events on the boat. The most famous excursion the boat ever took occurred in 1919, when the Prince of Wales visited the South Okanagan. The SS Sicamous carried the prince from Penticton to Okanagan Landing, with only one short stop at Summerland.

The launch of the SS Sicamous coincided with the construction of the Kettle Valley Railway to Penticton. The railway was constructed between 1910 and 1916. It changed the landscape of transportation in the South Okanagan. The line was a nearly impossible marvel of engineering, cutting through three treacherous mountain ranges on its way to the coast. It reached Penticton, which had been chosen as the railway's headquarters, in 1914.

The Kettle Valley Railway made getting to the coast an easy experience. No longer did the residents of the South Okanagan have to cross the Hope Mountains on horseback to reach Vancouver, or else make the long journey up the lake. The railway also solidified Penticton's position as the biggest town in the region. Construction workers and businessmen flooded into the town. For many, Penticton became a roadstop between the railway and the smaller towns of the Okanagan. Travellers would arrive in the region on the Kettle Valley Railway, spend the night in Penticton, and then board the SS Sicamous in the morning to continue their journeys.

The era of luxury steamships did not last long, however. By 1936, the Sicamous had been retired. Automobile use was increasing, and with improvements being made to the roads, the empire of the Canadian Pacific Railway was fading away. Today, the Sicamous has a place on the shores of Okanagan Lake. She is beached there and now serves as a museum and historical landmark. She has spent far longer beached than she ever spent plying the waters of Okanagan Lake.

You are now approaching the village of Kaleden, nestled between Highway 97 and the shores of Skaha Lake. Make a left on Lakehill Road away from the highway and descend the hill into village. Follow this road all the way to the lakeshore and park near the ruined concrete walls of the Kaleden Hotel. Don't worry—they are hard to miss.

Kaleden is a small village, but there is still plenty to do here. Learn the story of the Kaleden Hotel with our Story Location at this spot. Or, browse our other then-and-now photo opportunities throughout town. Visit the Linden Gardens and Frog City Cafe or go for a swim at the beach.

There are also plenty of interesting historical landmarks nearby. To visit the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory and learn about it through our On This Spot story location, travel back to Highway 97 and drive south until you reach White Lake Road. Take a right here and take this road all the way to the observatory. It will be on your left after a drive of approximately 13 minutes. Check before you go to see if they are currently offering guided or self-guided tours, and bring your binoculars—the area of White Lake is a popular spot for birders. It is located in an official Important Bird Area of Canada.

Another historical site in the area with a long history is the See Ya Later Ranch. It was once the property of a prominent South Okanagan community member, Major Hugh Fraser. Today, it is one of the highest elevated vineyards in the South Okanagan. To get there, take our next tour segment and travel to Okanagan Falls along Highway 97. Before you cross the bridge into town, however, turn right onto Green Lake Road. Follow this for five and a half kilometres. The vineyard will be on your left. On This Spot's story location "See Ya Later Ranch" shares the history of the eccentric, larger-than-life Major who once made this property home.

In the next segment of the tour, we will learn about the history of wildfires in the South Okanagan. We will investigate what makes this region so susceptible to fire and look at some of the worst fires that have burned through the region in the last fifty years.

6. Kaleden to Okanagan Falls

From Kaleden we will travel south to the town of Okanagan Falls, once known as "Dog Town." From the Kaleden Hotel, travel back up Lakehill Road to the highway. Make a left and continue south along the shores of Skaha Lake for seven kilometres.

On this segment of our tour, we will learn about the history of wildfires in the South Okanagan, and how this summer-time threat is becoming more and more common and dangerous. We will look into the factors which make this area so susceptible to fire, and explore some of the worst fires in the area to date. We will also look at what it takes to control and subdue these great blazes.

* * *

But this, of course, comes with seasonal risks. The heat and dryness increases the risk of wildfires. And the temperatures are only increasing year by year as climate change takes effect. In 2021, heat records were smashed during a historic heatwave.In Osoyoos, a 2002 temperature record of 39.3 degrees Celcius was broken on June 26th, 2021. Temperatures soared to 40.1 degrees Celsius.

Throughout the last thirty years, there have been many wildfires in the region that have claimed houses and burned thousands of acres of forest. In 1994, a major wildfire raged near Penticton. 3,500 people were evacuated and 5,500 hectares burned. Eighteen homes and other structures were destroyed in this blaze.

Nearly ten years later, the Okanagan Mountain Park Wildfire burned over 25,000 hectares, hitting the region hard. Kelowna was the worst affected communities in the valley. Over 33,000 people evacuated and 238 homes destroyed. The fire is still remembered today for its ferocity and the difficulty which was undergone to control it. The fire also had a grave effect on historical preservation in the region. It reduced twelve historic train trestles to ash in Myra Canyon, near Kelowna.

Controlling and subduing wildfires is a difficult task that the Province of BC has been pouring an increasing amount of resources into each summer. Fires need a combination of fuel, heat, and oxygen to burn. Putting them out involves the suppression of at least one of these factors. On-the-ground firefighters spray water and fire retardant onto the flames or else shovel dirt onto areas of fire to remove the oxygen crucial to the flame's survival. Water-bomber helicopters are also used, with Penticton Regional Airport being the primary hub for fire fighting aircraft for the region. In the Okanagan, these vehicles scoop water from the area's many lakes to dump onto the flames.

While attempts are made to put out the fire, other firefighters create lines of defences on the outskirts of the fire area to stop the flames from spreading. So-called "control lines" are created by removing or burning away all flammable material in a line around the fire. This is done to make it harder for it to spread once it reaches this spot. However, high winds often make this tactic extremely difficult. The winds allow the fire to jump large distances, or else reroute the flames around the control lines. Fires are a threat which constantly evolve, and which we can expect to face more and more frequently as the years go by.

You are now approaching Okanagan Falls. You will know you have reached the town when you cross the Okanagan River near the large dam which controls its waterflow. Once across the bridge, turn left on Cedar Street to get to Christie Memorial Park and enjoy the Skaha Lake waterfront.

There are a total of forty then-and-now photo opportunities in Okanagan Falls, along with three fascinating Story Locations. In Christie Memorial Park, visit the statue of the Salmon Chief and learn the story of the missing falls of Okanagan Falls. Or, walk across the Okanagan River on the historic Kettle Valley Railway bridge. Read our Story Location on the founding of Dog Town and the big dreams its founders had for it. To visit our third story location, find the statue of rodeo legend Kenny McLean in Centennial Park. Learn about the stockyards and the history of rodeo in Okanagan Falls. While you're here, you can also visit the historic Bassett House and Museum on Main Street or try the ice cream at Okanagan Fall's famous ice cream parlour, Tickleberries.

In the next segment of the tour, we will learn about fruit growing and wine production in the South Okanagan. We will trace the transformation of the Okanagan from desert land to orchards to vineyards and look at some of the many challenges which faced early farmers.

7. Okanagan Falls to Oliver

Once you have explored Okanagan Falls, we will continue south to the town of Oliver. This town is one of the youngest in the South Okanagan but is still home to a wealth of interesting history. From Christie Memorial Park in Okanagan Falls, travel east on 7th Avenue until you reach Main Street, where you can make a right. Main Street quickly becomes Highway 97. We will travel on the highway for the rest of the 18 minute journey between towns. The route travels through vineyard and orchard land and past Vaseux Lake.

In this segment of the tour, we will dig into the history of agriculture in the South Okanagan, tracing the growth of the industry from cattle ranching to fruit growing to wine production. As you make your way towards Oliver, keep an eye on the many lush vineyards on either side of the road. The town of Oliver is known as the "Wine Capital of Canada" and is home to more than 40 wineries.

* * *

The first "crop" raised in the South Okanagan was not fruit at all, but cattle. The cattle kings, Tom Ellis and John Carmichael Haynes, dominated the ranching industry at the end of the nineteenth century. Each owned tens of thousands of acres of land. Their herds roamed throughout the southern valley.

Yet cattle raising requires vast quantities of land. The increasing speed of settlement in the beginning of the twentieth century spelled the end of the ranching era. When Tom Ellis sold his land in 1905, he sold it not to another ranching king, but to a development company: the South Okanagan Land Company. The company, owned by the Shatford brothers, transformed much of the property into orcharding land. The transition from ranching to fruit growing began in earnest.

The first fruit trees in the Okanagan, however, were planted nearly fifty years earlier by Hiram F Smith. His orchards were located at a spot which is now south of the United States/Canadian border. Smith planted over 1,000 fruit trees in 1857, kicking off an industry which would come to define the Okanagan.

Smith originally worked as a packer for the Hudson's Bay Company. It was likely from this company that he acquired his first trees. They were carried into the valley from Hope and likely came from Fort Langley, where the Hudson's Bay Company operated a nursery. Smith sold much of his apple harvest to the gold miners and cattle ranchers travelling north through the Okanagan Valley. He dried the fruit, making it more easily transportable for these travellers.

On the Canadian side of the border, Tom Ellis planted his first fruit trees in 1869 near Penticton. He did not aspire, as Smith did, to have a large orchard, however. For many years, the trees remained a small side crop while Ellis focused his energy and resources on the cattle business.

In the following decades, orchards began to slowly creep across the South Okanagan. In Summerland, a settler by the name of Mr. Gartrell planted orchards in the Garnett Valley in 1892. Eight years later, the first orchards in Okanagan Falls were planted. In Peachland and Naramata, real estate developer J.M. Robinson planted orchards in 1901 and 1905, respectively. Farther south, in Osoyoos, Leslie Hill planted over 30 acres of fruit trees in 1907.

The 1890s and the first decade of the twentieth century represented a boom in the industry of fruit growing. Both experienced and new farmers flocked to the region with big dreams of agricultural success. Yet fruit-growing was not the easy, money-making scheme that many of the farmers assumed it would be. Early fruit growing was an industry fraught with challenges at every angle. As D.V. Fisher of the Dominion Research Station in Summerland said:

"Great hardships were endured by the pioneer orchardists because of totally inadequate irrigation systems, recurrent winter freezes, the planting of numerous and unsuited varieties, minor element deficiencies, the invasion of codling moth which became an epidemic in 1925, and above all, by repeated failures to establish a sound marketing system backed by unified grower support."

Yet one of the largest, most glaring problems in a lot of ways was the naive optimism with which many of the South Okanagan's newest farmers approached the business of fruit growing. Many came from the prairies. They had been sold a farming dream by the real estate developers of the South Okanagan. As one early pioneer said:

"I came to the Okanagan Valley with the idea, common to many travelers from the Prairies, that growing fruit-bearing trees is easy. You plant the tree, wait until the crop is ready, then harvest the perfect, abundant fruit. As I became involved in orcharding, I realized that nothing could be further from the truth; in fact, it is an extremely complicated endeavor and its complexity increases with time."

Still, these early orchardists persevered. Settlers grew apples, peaches, plums, cherries, apricots, and pears. Ground crops such as melons, cucumbers, tomatoes and carrots were grown in the rows between trees. This provided a secondary income for the struggling fruit growers. Early orcharding was accomplished with little equipment. Fruit packing and processing was originally done on the farm site itself. All of the horse-power needed in operations was provided by actual horses.

Gradually, knowledge bases in the Okanagan increased, and farming grew easier. The Dominion Research Station in Summerland helped this process along. This government-funded facility was devoted to agricultural research with the goal of helping the region's farmers thrive. It investigated which crops grew best in the South Okanagan climate, looked at ways to prevent diseases and pests such as codling moths, and experimented with plant varieties.

Another massive improvement in the farming industry was the creation of reliable systems of irrigation throughout the South Okanagan. In the early years of farming, water shortages were a major difficulty for all farmers. Originally, the creation of irrigation systems was the responsibility of land developers. Thus, these systems varied in their efficiency depending on the wealth of the developer in question.

Landowners would purchase and subdivide land with the intention of selling it to farmers. However, a plot of land without irrigation only sold for between $10 and $40 an acre. An irrigated plot could go for as much as $350. Even developers who didn't have the resources to create fully functional irrigation systems would try to do so. This left plenty of farmers with shoddy, inefficient systems. Government intervention eventually solved the irrigation problem, at least in the southern part of the valley near Oliver and Osoyoos. The BC Government under Premier John Oliver founded the South Okanagan Lands Project in 1918, although the local sukʷnaʔqinx First Nations opposed this project, since it involved the theft of much of their land. Their representatives travelled to Ottawa in a fruitless attempt to stop it.

Throughout the next several years, this project worked to create a massive irrigation system to transform the desert land into lush farmland. The goal of the project was to create a farming community where returning soldiers of the First World War could buy cheap, arable land. The resulting town was named after its founder: Oliver.

The 1930s were a time in which fruit growing became a far more viable economic option. New technology and improved irrigation systems combined to increase the profitability of the industry. The density of orchards increased, with more trees, and therefore more fruit, packed into smaller and smaller spaces. Large packing houses operated in each community, preparing fruit for market on larger scales. The arrival of the Kettle Valley Railway to Penticton in 1916 made export of fruit from the valley to larger markets more viable.

Throughout the beginning of the 1930s, however, one major challenge still faced the fruit growers of the South Okanagan. The market they sold to was unstable and difficult to reach. The farms in the region produced far too much fruit for the local populations to consume. This meant farmers faced the challenges of packing and transporting fruit in an era before much of the technology for food preservation had been invented. It was an expensive process, especially when the markets were as unstable as they were.

At the beginning of the decade, there were a total of thirty-seven fruit selling agents in the South Okanagan. This wealth of shipping and selling organizations created competition that caused prices to fluctuate and dip. In 1939, the fruit growers of the South Okanagan came together to solve this problem. They created the BC Fruit Growers Association, which in turn established BC Tree Fruits Limited. This organization acted as the sole marketing agency for Okanagan fruit, replacing every other selling agent. Now, the farmers could set their own prices and hold them stable. The fruit industry became far more profitable and successful once the chaotic marketplace had been controlled.

The BC Fruit Growers Association went on to create the BC Fruit Processing Limited Company in 1946 to handle processed fruit products in the Okanagan. The company took apples and other fruit that would otherwise have been thrown away and turned them into profitable juice products. Thirteen years later, this company changed its name to Sun-Rype Products. Today, it is well-known across Canada for its fruit juices and other products.

As the fruit growing industry expanded, it also became more diverse. In the beginning of the industry, in the late nineteenth century, it was dominated by farmers from the British Isle or from the Alberta prairies. Yet this soon changed. In the early twentieth century, many Japanese immigrants settled in the South Okanagan. Most began their careers working for the Canadian Pacific Railway or for already established fruit growers. Many were gradually able to acquire their own lands, however.

In the aftermath of the First World War, these Japanese-Canadian fruit growers were joined by a large population of German immigrants. These immigrants were hoping to escape the poor economic prospects in Europe. After the Second World War, more European immigrants flocked to the Okanagan. Hungarian and Portuguese immigrants settled in the Okanagan in the hundreds. Like the Japanese immigrants before them, most began their careers as farm labourers. And, like the Japanese-Canadians, they soon acquired their own farming lands. More recently, in the 1980s, a population of Sikh farmers settled in the South Okanagan and took up fruit growing. This diverse cultural make-up has only strengthened both the culture of the South Okanagan and its fruit growing industry.

Yet even as the fruit industry in the Okanagan was beginning to truly thrive in the late 1930s, a new change in the agricultural industry of the South Okanagan was already on the horizon. While the Okanagan is still known for its fruit growing, its main claim to fame nowadays is its vineyards and wineries.

The first grapes in the Okanagan were planted near Kelowna by Father Pandosy at the Oblate Mission in 1859. Yet these were largely for ceremonial purposes, and it took many more decades for the industry to develop any further. The crop may have taken off quicker if not for BC's short-lived Prohibition era, which lasted from 1917 to 1921. During this time, the few small vineyards which had taken shape were forced to remove their grape crops. The industry was effectively brought back to square one.

After Prohibition ended, grape growing was slow to pick up speed once more. In 1926, J.W. Hughes planted grapes near Kelowna, eventually expanding to 300 acres of vines. In the South Okanagan, near Oliver, the Rittich brothers experimented with different varieties of grapes throughout the 1930s. These men, who were Hungarian immigrants, first brought to the valley some of the grape species which are now immensely popular in the region.

Wine production in the South Okanagan got its first major boost during the premiership of W.A.C. Bennett. Bennett was himself personally invested in the wine industry in BC and therefore worked hard to promote the industry. He was one of the original partners in the Calona Vineyards near Kelowna.

Bennett's government pushed to increase the amount of BC grape juice which a wine needed to include in order to be labelled as BC wine. This number was set at 50% in 1962, and soon rose to 80%. Grape production rose with it, as wineries included higher and higher percentages of BC grape juice in their products. The 1961 BC grape harvest was 1,600 tonnes. By 1970, BC was producing over 9,000 tonnes of grapes.

Two major events took place in the late 1980s which firmly cemented BC's young grape industry in the culture of the province. The first was a mixed blessing: The Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement of 1988. The free trade agreement removed the tariffs on imported wines that had previously protected local products. While this threw the Okanagan's wine industry into chaos in the short-term, it also caused the wineries of the South Okanagan to up their game. With increased competition, the quality of BC's wines improved.

The second event to transform BC's wine industry was the introduction of the European vinifera grape varieties. These varieties produced wines of a higher quality than the local native grapes. In 1989, the BC Government sponsored vineyards to pull the native grapes and replace them with the European varieties. This effort was intended to boost the quality of wine in the South Okanagan. In total, the government devoted $28 million to the task of replacing the old vines with the new. South Okanagan wine improved once more.

Since the 1980s, the wine in the South Okanagan has only gotten better as the industry expands. The creation of both the BC Wine Institute and the Vintners Quality Alliance in 1990 created quality control agencies. And in 1994, Okanagan wine was put on the world stage when the Mission Hill Winery won the award for Best Chardonnay at the International Wine & Spirit Competition.

Today, wine production is as big a part of the cultural and economic fabric of the South Okanagan as fruit growing was in the early twentieth century, or cattle ranching before that. The climate and environment of the South Okanagan continues to nourish and support its residents.

You are now entering the town of Oliver. Once the highway turns into Main Street, make a left on Veterans Avenue and park at the Oliver Visitor Centre on Station Street. Along with over thirty then-and-now photo opportunities, there are two Story Locations in the main town of Oliver and one, for the adventurous, outside of it. Learn about the Syilx Okanagan First Peoples at your current location. Or, travel to the Kinsmen Spray Park and the nearby Okanagan River. Here, you can learn more about the complicated system of irrigation that was built in the early 1920s to transform the desert lands of the South Okanagan into lush agricultural land.

Our third Story Location takes visitors out of Oliver and up into the hills to visit the site of Fairview. This mining town was once one of BC's biggest communities, yet rapidly became an empty ghost town. Learn the story of this famous boom-and-bust town, which epitomizes the fate of so many similar mining communities across BC. Not only is the history of this spot fascinating, but the view isn't bad either!

Our next tour segment explores the history of women in the South Okanagan. We will also learn about the development of community organizations, medical services, and education within the region.

8. Oliver to Osoyoos

Our last leg of the journey will take us from Oliver to the town of Osoyoos near the United States and Canadian border. Osoyoos is home to the warmest lake in Canada and has a rich culture of fruit and wine growing. To get to the town, return to Oliver's Main Street and continue south. Main Street will turn into Highway 97, which will take you all the way to Osoyoos. It is a journey of approximately twenty minutes.

In this final tour segment, we will follow the early development of the communities of the South Okanagan, paying special attention to the roles of women. We will look at the history of community organizations, schools, and medical services. We will explore what it was like to live in a South Okanagan community in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

* * *

Powerful settler men such as John Carmichael Haynes, C. O'Keefe, and J.F. Allison lived with unmarried Indigenous women. In some historical texts, these relationships are painted in a positive light as bonds which survived despite the lack of legal and ceremonial matrimony. In others, these Indigenous women are referred to as "concubines", exploited by their white partners. Likely, bonds of affection and intimacy did exist. Yet the likelihood that a degree of exploitation took place in these relationships is also extremely high. There was a clear power imbalance within these couples.

White and Indigenous unions were common during the 1860s. Scholar Duane Thomson estimates that of the thirteen most powerful settlers in the region, half had Indigenous children. Of the men on the 1874-1877 provincial voters list for the Okanagan, a third of those outside of the Okanagan Mission had had children with an Indigenous wife or mistress. And many of the early local schools in the regions were filled almost entirely with half-Indigenous children.

Yet as more and more European women gradually began to arrive in the region, many Indigenous women were abandoned by their white partners. Because the unions were often not solidified legally, these European men were under no obligations but their own consciences to provide for their Indigenous wives and children. Many still did, but not all of them. And most of these men went on to marry the arriving European women instead. Many married arriving women who were decades younger than them.

In the 1860s and 1870s, relationships between white men and Indigenous women were, to a large degree, culturally and socially acceptable. Yet as the century progressed and white women arrived in the region, men who remained with their Indigenous partners began to be reviled by European society. Both partners were looked down upon.

Men such as Henry Shuttleworth, a European immigrant who had legally married an Indigenous woman, struggled to gain employment. During his quest to get a teaching position, Shuttleworth complained to the local superintendent of education that no one would give him a job.

He said that, "I suppose it is because I have an Indian Woman but I can assure you and if necessary also prove to you that I am lawfully married to her."

More commonly, however, white men abandoned their Indigenous partners rather than face this stigma. In Osoyoos, J.C. Haynes had three children with his partner Julia, a Colville Indigenous woman. Yet in 1868, he married a white woman half his age. Upon her death in child-birth, he soon married another European woman.

Also in Osoyoos, Theodore Kruger abandoned his Indigenous partner with whom he had had at least two children. He instead married a sixteen-year-old Danish girl who had just arrived in the Okanagan. Kruger was 44 at the time.

The children of these early mixed-race unions faced many challenges. For one thing, not all were provided for by their white fathers. Some, such as the Indigenous sons of J.C. Haynes, were educated and given land holdings. Others had to make their own ways in an unforgiving world.

And most often, these children were ignored by early historians and swept into the background by their own fathers. They became an invisible generation, their existences denied in public. Kruger's Indigenous daughter Matilda worked as a servant in the Haynes' household. Haynes' own Indigenous daughters were referred to as "waitresses and housemaids" by a European settler who visited the house. In historical records, the children born to these men by their European wives were referred to as their eldest children. This was despite the many Indigenous children born to them years beforehand.

In the 1870s, more and more white women began to arrive in the Okanagan. Previously, there had been only about five to settle in the region. As settlement increased, so did the population of European women. As new communities emerged, the one on which the early European society in the Okanagan had been founded was pushed to the side. Society became more segregated and racist.The predominantly white communities recorded in much of our history texts took shape.

Throughout the history of the South Okanagan, women shaped the communities they lived in. While history tends to focus on the accomplishments and exploits of men, women nonetheless held a quiet and undiminished power to transform their societies. Women in the Okanagan founded community organizations, taught in schools, managed their own properties, and served as postmistresses, shopkeepers, and governesses.

One of the most popular and long lasting women's organizations which existed all across the country was the Women's Institute. There were branches of the Women's Institute in almost every community in the South Okanagan. These groups worked towards crucial improvements in the welfare of their communities. They raised funds for war efforts, built community halls, and sponsored education and health care organizations.

In Oliver, for instance, the Women's Institute was founded in 1922 and was still in existence 93 years later in 2016. During that time, the group acquired land for the first hospital, brought nursing services to Oliver, established immunization clinics, and supported the birthing unit at the South Okanagan General Hospital. They also provided bursaries for graduating students, started home economic classes in schools, advocated for clean water for the rural district, and gave out food and clothing hampers to those in need.

In Osoyoos, the Women's Institute was also active in increasing health services for the community. They also sponsored groups such as the Girl Guides and Boy Scouts and worked to remodel the Community Hall. During World War II, the Osoyoos Women's Institute sent care packages to every Osoyoos resident who was serving overseas. They worked closely with the Red Cross, another women-led organization which devoted itself to the war efforts.