Forced Labour in Yoho Park

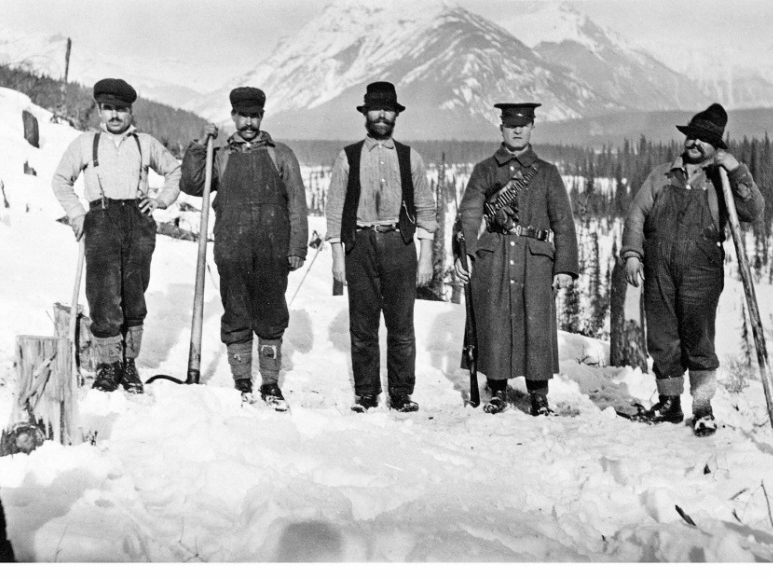

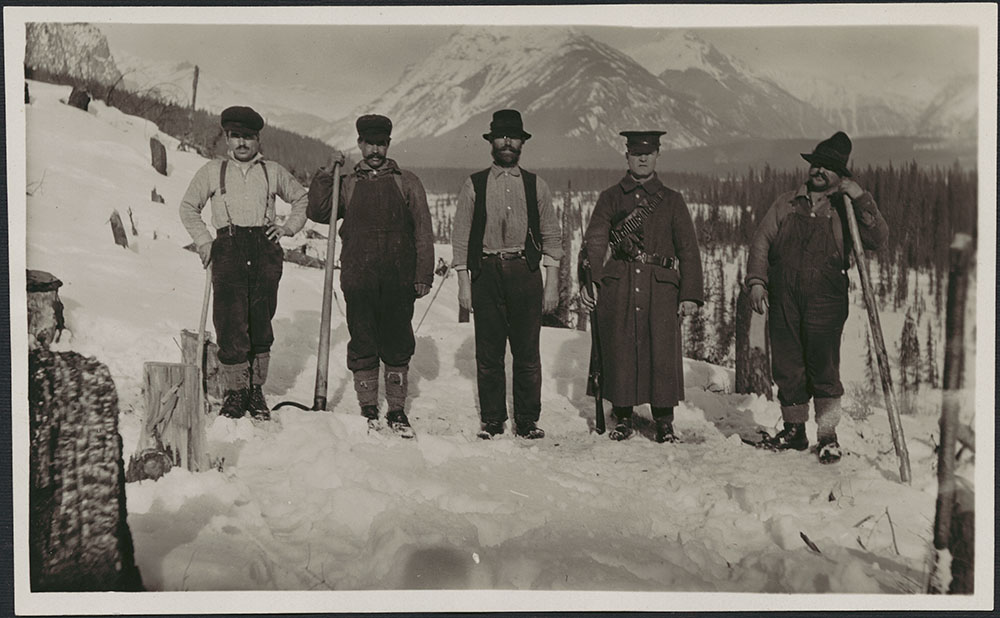

Chief among Canada's finest natural wonders are its beautiful and awe-inspiring national parks. Few today know however, the link between some of these parks and Canada's First World War internment operations. In the Rocky Mountains, Austro-Hungarian prisoners interned for their nationality labored on park infrastructure projects such as land clearing and road construction. The Otter Internment Camp, shown in the photo above, was located in the Kicking Horse River Valley, not far from the community of Field, British Columbia. From October 1915 to April 1916, this camp held 200 internees who endured the freezing cold, snow storms, and isolation through the winter months while they did back-breaking labour for Yoho National Park.

* * *

Internment camps in the Rockies began as a result of a conversation between Major General William Otter, the director of internment operations, and J. B Harkin, dominion parks commissioner. Due to the war, resources for the development of national parks were reduced by half, and Harkin was keen to make up for the loss. The use of internee labour, which was a fraction of what regular labour would cost, was an attractive solution.

Harkin began with Rocky Mountains National Park, which is today known as Banff National Park. He submitted a proposal to W. J. Roche, the Minister of the Interior, which outlined the construction of an internment camp at Castle Mountain, near the town of Banff, Alberta. Roach agreed to the idea, preferring to put the internees to work rather than, "allowing them to eat their heads off."1

Internees at work building the rough log buildings that would house them during the winter.

Internees at work building the rough log buildings that would house them during the winter.

By July 1915, the Castle Mountain Camp was established, and soon filled with 191 prisoners who were swiftly put to work. Harkin was pleased with the work, and soon sought out additional projects that would benefit from internee labour. Next, he considered the newly created Mount Revelstoke National Park. Local business owners thought that a road to the summit of Mount Revelstoke would attract visitors who would ultimately spend money at the town's businesses. Harkin and General Otter agreed and set to work establishing an internment camp at Mount Revelstoke. However, once the camp was established, it soon became clear that the site was entirely unsuitable. The location was cramped and less than ideal, and there was also limited access to drinking water. Soon the camp's 200 internees began to protest the poor conditions, which were only worsened by bad weather, and their treatment in camp. Ultimately internment officials made the decision to close the camp and relocate the internees.

The closure of the Revelstoke camp caused officials to scramble to locate a suitable replacement site to house the internees. However, Harkin, in his enthusiasm for internee labour, had asked the superintendent at Yoho National Park, E. N. Russell to propose any future potential projects for internee labour prior to the problems at Revelstoke. Russell rose to the challenge and found a project that was of particular interest to officials. A forest fire had recently burned a large stand of trees at the confluence of the Ottertail and Kicking Horse Rivers, near the town of Field, BC, and he believed the timber was still salvageable. The timber could be sold at market and had the potential to generate a tidy profit. If internees could be tasked with felling the scorched timber, it only increased the potential profit margins.

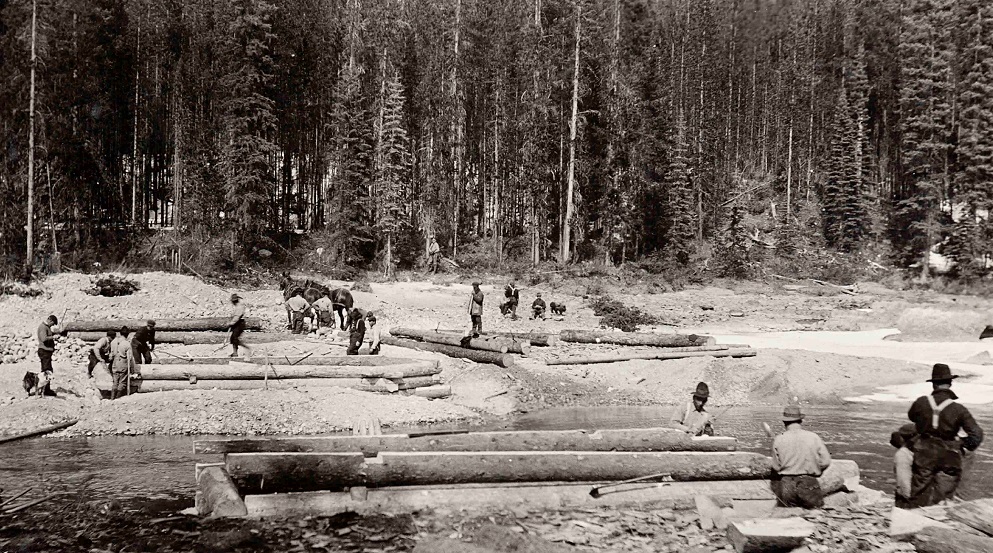

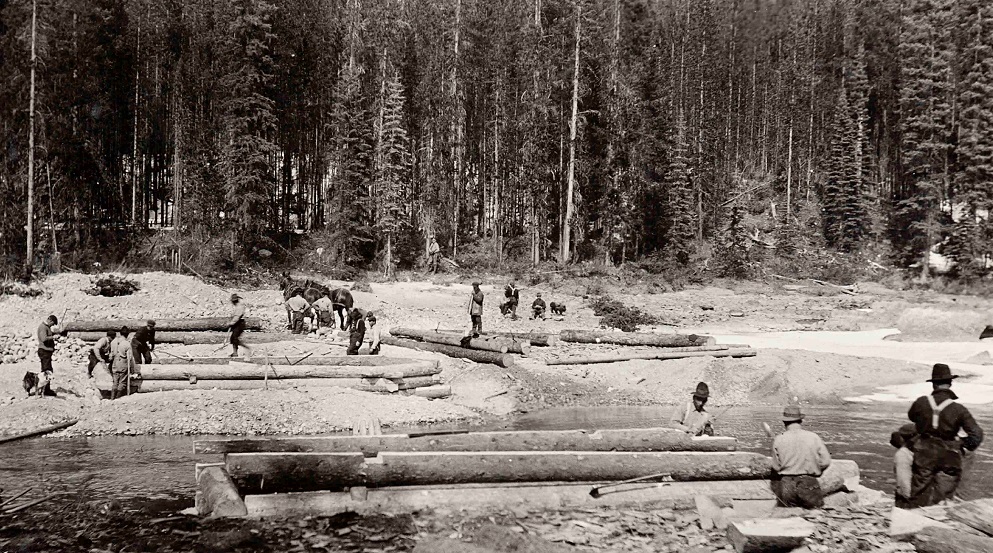

A group of internees working on the foundations of a bridge to cross the Ottertail River.

A group of internees working on the foundations of a bridge to cross the Ottertail River.

The first crew of 50 internees arrived in late October and began to assemble camp buildings, and the rest of the internees followed in December. As the road work began, Superintendent Russell, and parks commissioner Harkin disagreed over how the work should progress. A scenic route connecting Ottertail River to the Natural Bridge on the Kicking Horse was planned, but Russell believed the winter conditions would make roadwork impossible, and that the internees should focus on removing the burnt timber then postpone the road work until the spring. Harkin thought both were entirely possible, and set the internees to complete the logging work as quickly as possible before starting road work.

However, by mid-January, doing any kind of work became impossible. High winds and frigid temperatures caused blizzards to sweep through the mountains, and internees were driven to shelter in camp. For that month, the only priority was survival. Firewood was in constant demand, and the camp had to be cleared of snow frequently as the accumulation threatened to overwhelm the camp entirely. Under these conditions only three days of actual road work were possible over the month.

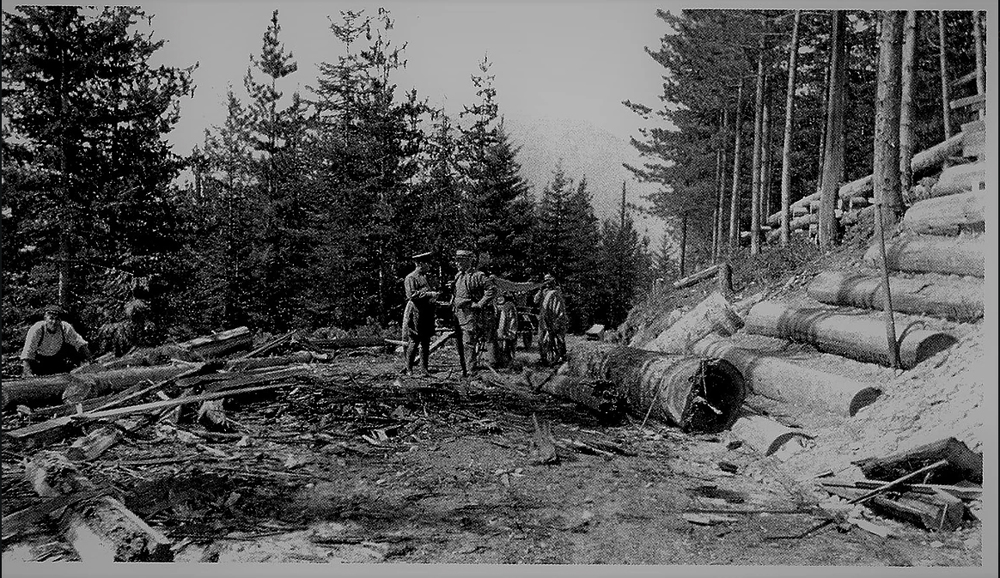

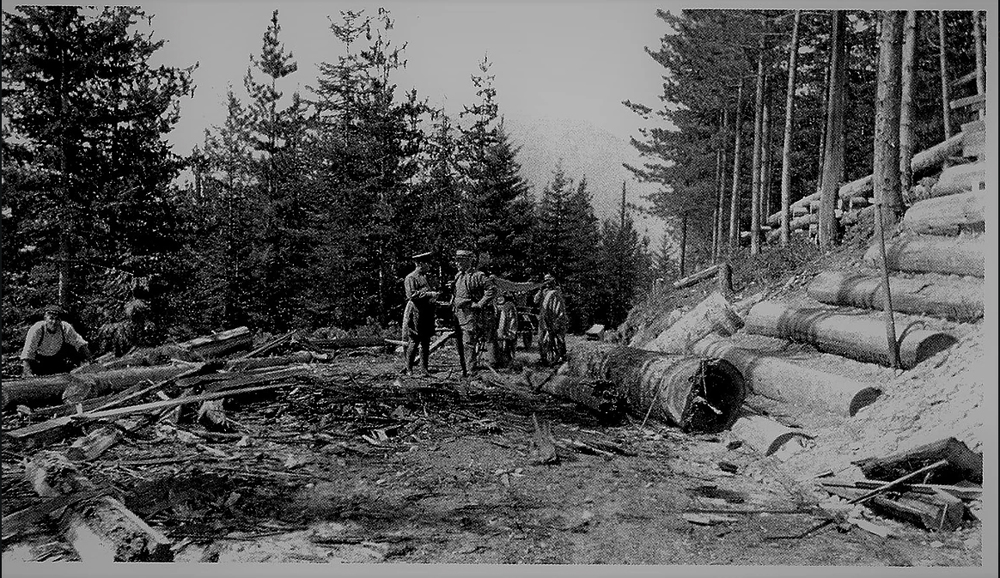

Road construction underway at Yoho National Park.

Road construction underway at Yoho National Park.

Finally, in late February the weather cleared and the internees were again sent out to perform their grueling tasks. They soon realized that the delay caused by the weather would only worsen their circumstances as camp officers and internment officials pushed them even harder to make up for lost time. In an effort to improve productivity, officials ordered internees to cut a direct trail from camp to the worksite. They also took advantage of the longer days and increased the work day from seven to eight hours. As these measures were introduced, Russell urged the internees to increase the pace as they walked to work, and pushed them to work faster, harder, and longer.

The internees had been pushed too far. They began refusing to work. The tension between the internment operatives and the internees continued until April, when spring floods threatened to cut the camp off from its supply base. Officials soon ordered another camp move, hopeful that a change in location would improve the camp mood.

The new summer camp was located at the confluence of the Boulder and Kicking Horse Rivers, and the internees moved in June. However, things did not improve. This camp would prove just as unbearable as the previous two. The spring floods were worsened by torrential rains. Flooding soon caused the entire camp to evacuate to higher ground. They were not alone however, the town of Field was also threatened with flooding. So the internees were sent in to help save the town.

The frosty winter and wet spring soon gave way to blistering heat, while the sodden landscape birthed vast swarms of biting insects. The work conditions were impossible. By August, the internees had had enough. They began to strike, and argued staunchly against their internment, stating they could not fathom "why they should be interned when hundreds of other alien enemies are allowed not only to go free, but to earn their living in the country."2

A view of camp guards outside the barbed wire fence observing the prisoners on the other side.

A view of camp guards outside the barbed wire fence observing the prisoners on the other side.

As their complaints continued to fall on deaf ears, the Yoho internees feared they would be forced to return to the winter camp. This concern, and the news that the prisoners at the Morrissey camp were no longer working, only strengthened their resolve to continue their strike. Camp officers responded with punishment, cutting rations and stripped the internees of their privileges. Yet these measures were ineffective. Camp Commandant Lieutenant Brock resisted pressure from his superiors to use more severe forms of punishment. He and E. N. Russell both believed that even harsher measures would fail to get the desired result. They both recommended closing the camp permanently.

Major General Otter was not convinced. He believed the problem rested solely with the camp command, and ordered that the officers be changed out, and the camp transferred back to the winter quarters. Little did he know that the internees had no intention to stick around when the transfer occurred.

As summer drew to a close, the internees plotted their escape. Using kitchen cutlery and a single shovel, they began to dig a tunnel that would take them under the barbed wire. They were very close to achieving their goal when they were discovered. According to the guards, the internees had been in possession of crude weapons when they were found. Although the escape had been prevented, the entire situation made officials uneasy. The internees were spared from their return to the winter camp when officials made the decision to close the camp for good. However, their actions caused officials to label these prisoners as problematic, and the majority of the Yoho/Field camp internees were sent on to Spirit Lake camp in Quebec. While internment officials bemoaned the loss of labour required to complete the project, they still reaped a considerable reward from the unwilling and unco-operative inmates. The burned timber they had removed was processed into railway ties, pulling in a profit of about $16,000, or around $325,000 today.3

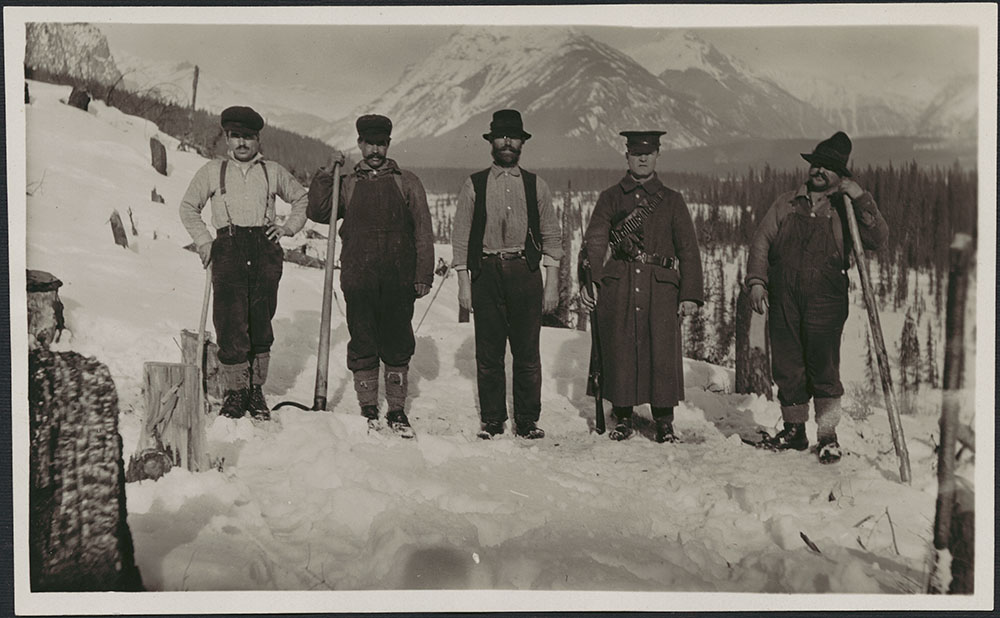

Three internees take a break from work to stand for a photo while a guard stands between them. Even while gathering for a photo, these internees are under armed guard.

Three internees take a break from work to stand for a photo while a guard stands between them. Even while gathering for a photo, these internees are under armed guard.

While the camp was closed, it was never dismantled. Some evidence still remains today of the camp buildings. In 2019, the Ukrainian-Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA) partnered with Parks Canada to erect a trilingual plaque at the Yoho site memorializing the victims of internment in Ukrainian, English, and French. The Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund (CFWWIRF) also contributed to the memorial by adding in a statue. John Boxtel sculpted the standing figure of an internee and titled the piece “Last Man Standing.” This memorial stands to help raise awareness of Canada's First World War internment operations, an injustice that sadly still many Canadians are unaware of today

Harkin began with Rocky Mountains National Park, which is today known as Banff National Park. He submitted a proposal to W. J. Roche, the Minister of the Interior, which outlined the construction of an internment camp at Castle Mountain, near the town of Banff, Alberta. Roach agreed to the idea, preferring to put the internees to work rather than, "allowing them to eat their heads off."1

By July 1915, the Castle Mountain Camp was established, and soon filled with 191 prisoners who were swiftly put to work. Harkin was pleased with the work, and soon sought out additional projects that would benefit from internee labour. Next, he considered the newly created Mount Revelstoke National Park. Local business owners thought that a road to the summit of Mount Revelstoke would attract visitors who would ultimately spend money at the town's businesses. Harkin and General Otter agreed and set to work establishing an internment camp at Mount Revelstoke. However, once the camp was established, it soon became clear that the site was entirely unsuitable. The location was cramped and less than ideal, and there was also limited access to drinking water. Soon the camp's 200 internees began to protest the poor conditions, which were only worsened by bad weather, and their treatment in camp. Ultimately internment officials made the decision to close the camp and relocate the internees.

The closure of the Revelstoke camp caused officials to scramble to locate a suitable replacement site to house the internees. However, Harkin, in his enthusiasm for internee labour, had asked the superintendent at Yoho National Park, E. N. Russell to propose any future potential projects for internee labour prior to the problems at Revelstoke. Russell rose to the challenge and found a project that was of particular interest to officials. A forest fire had recently burned a large stand of trees at the confluence of the Ottertail and Kicking Horse Rivers, near the town of Field, BC, and he believed the timber was still salvageable. The timber could be sold at market and had the potential to generate a tidy profit. If internees could be tasked with felling the scorched timber, it only increased the potential profit margins.

The first crew of 50 internees arrived in late October and began to assemble camp buildings, and the rest of the internees followed in December. As the road work began, Superintendent Russell, and parks commissioner Harkin disagreed over how the work should progress. A scenic route connecting Ottertail River to the Natural Bridge on the Kicking Horse was planned, but Russell believed the winter conditions would make roadwork impossible, and that the internees should focus on removing the burnt timber then postpone the road work until the spring. Harkin thought both were entirely possible, and set the internees to complete the logging work as quickly as possible before starting road work.

However, by mid-January, doing any kind of work became impossible. High winds and frigid temperatures caused blizzards to sweep through the mountains, and internees were driven to shelter in camp. For that month, the only priority was survival. Firewood was in constant demand, and the camp had to be cleared of snow frequently as the accumulation threatened to overwhelm the camp entirely. Under these conditions only three days of actual road work were possible over the month.

Finally, in late February the weather cleared and the internees were again sent out to perform their grueling tasks. They soon realized that the delay caused by the weather would only worsen their circumstances as camp officers and internment officials pushed them even harder to make up for lost time. In an effort to improve productivity, officials ordered internees to cut a direct trail from camp to the worksite. They also took advantage of the longer days and increased the work day from seven to eight hours. As these measures were introduced, Russell urged the internees to increase the pace as they walked to work, and pushed them to work faster, harder, and longer.

The internees had been pushed too far. They began refusing to work. The tension between the internment operatives and the internees continued until April, when spring floods threatened to cut the camp off from its supply base. Officials soon ordered another camp move, hopeful that a change in location would improve the camp mood.

The new summer camp was located at the confluence of the Boulder and Kicking Horse Rivers, and the internees moved in June. However, things did not improve. This camp would prove just as unbearable as the previous two. The spring floods were worsened by torrential rains. Flooding soon caused the entire camp to evacuate to higher ground. They were not alone however, the town of Field was also threatened with flooding. So the internees were sent in to help save the town.

The frosty winter and wet spring soon gave way to blistering heat, while the sodden landscape birthed vast swarms of biting insects. The work conditions were impossible. By August, the internees had had enough. They began to strike, and argued staunchly against their internment, stating they could not fathom "why they should be interned when hundreds of other alien enemies are allowed not only to go free, but to earn their living in the country."2

As their complaints continued to fall on deaf ears, the Yoho internees feared they would be forced to return to the winter camp. This concern, and the news that the prisoners at the Morrissey camp were no longer working, only strengthened their resolve to continue their strike. Camp officers responded with punishment, cutting rations and stripped the internees of their privileges. Yet these measures were ineffective. Camp Commandant Lieutenant Brock resisted pressure from his superiors to use more severe forms of punishment. He and E. N. Russell both believed that even harsher measures would fail to get the desired result. They both recommended closing the camp permanently.

Major General Otter was not convinced. He believed the problem rested solely with the camp command, and ordered that the officers be changed out, and the camp transferred back to the winter quarters. Little did he know that the internees had no intention to stick around when the transfer occurred.

As summer drew to a close, the internees plotted their escape. Using kitchen cutlery and a single shovel, they began to dig a tunnel that would take them under the barbed wire. They were very close to achieving their goal when they were discovered. According to the guards, the internees had been in possession of crude weapons when they were found. Although the escape had been prevented, the entire situation made officials uneasy. The internees were spared from their return to the winter camp when officials made the decision to close the camp for good. However, their actions caused officials to label these prisoners as problematic, and the majority of the Yoho/Field camp internees were sent on to Spirit Lake camp in Quebec. While internment officials bemoaned the loss of labour required to complete the project, they still reaped a considerable reward from the unwilling and unco-operative inmates. The burned timber they had removed was processed into railway ties, pulling in a profit of about $16,000, or around $325,000 today.3

While the camp was closed, it was never dismantled. Some evidence still remains today of the camp buildings. In 2019, the Ukrainian-Canadian Civil Liberties Association (UCCLA) partnered with Parks Canada to erect a trilingual plaque at the Yoho site memorializing the victims of internment in Ukrainian, English, and French. The Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund (CFWWIRF) also contributed to the memorial by adding in a statue. John Boxtel sculpted the standing figure of an internee and titled the piece “Last Man Standing.” This memorial stands to help raise awareness of Canada's First World War internment operations, an injustice that sadly still many Canadians are unaware of today