Revelstoke Internment Camp

In the winter of 1915 this mountain was the site of a brutal ordeal for 200 Austro-Hungarian men imprisoned and under armed guard by Canadian soldiers. They were among thousands of civilians, many naturalized Canadian citizens, who were arrested because Canada had gone to war with their mother countries.

They were sent to a small camp near this site, and then forced to begin construction on the road to the mountain summit in September 1915. The project was ill-conceived from the outset. The camp was disastrously situated and had a haphazard water supply. The guards were cruel, abusing and overworking the prisoners. It also began to snow.

In just over a month further road construction became impossible. The camp was abandoned. The internees were dispatched to Yoho National Park where the Otter internment camp was being built.1

Today, Mount Revelstoke internment camp has almost completely disappeared. The site is overgrown with trees. If one looks closely, they can see the rotting wooden foundations of the bunkhouses. Rusted barbed wire is still ominously wrapped around some of the older trees. They are a painful reminder of a dark chapter of Canada’s history that is only in recent years getting the attention it deserves.

They were sent to a small camp near this site, and then forced to begin construction on the road to the mountain summit in September 1915. The project was ill-conceived from the outset. The camp was disastrously situated and had a haphazard water supply. The guards were cruel, abusing and overworking the prisoners. It also began to snow.

In just over a month further road construction became impossible. The camp was abandoned. The internees were dispatched to Yoho National Park where the Otter internment camp was being built.1

Today, Mount Revelstoke internment camp has almost completely disappeared. The site is overgrown with trees. If one looks closely, they can see the rotting wooden foundations of the bunkhouses. Rusted barbed wire is still ominously wrapped around some of the older trees. They are a painful reminder of a dark chapter of Canada’s history that is only in recent years getting the attention it deserves.

* * *

In 1915 Major General William Otter, director of internment operations, had a large pool of interned enemy aliens, mostly Ukrainians from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who were expensive to feed, house, and keep under armed guard. He began entertaining proposals to have them go and be forced to work on infrastructure projects. The Dominion Parks Commissioner J. B Harkin, proposed having them build a road up Mount Revelstoke, in Mount Revelstoke National Park, which had just been founded earlier that year.

Local business owners thought that a road to the summit of Mount Revelstoke would attract visitors who would ultimately spend money at the town's businesses. Harkin and Major General Otter agreed and construction began on the log buildings which would house the unwilling workforce.

Despite Otter's agreement and blessing for the new camp, he was disappointed when he came to Revelstoke to inspect the construction. The site was cramped, and the location was less than ideal. However, much of the work was already done, and crowding at the Brandon camp put pressure on the new camp to be completed quickly. He gave it approval and the first batch of 50 internees arrived in September. Another 150 prisoners arrived shortly after, bringing the total prisoner population to 200 along with 100 armed guards.

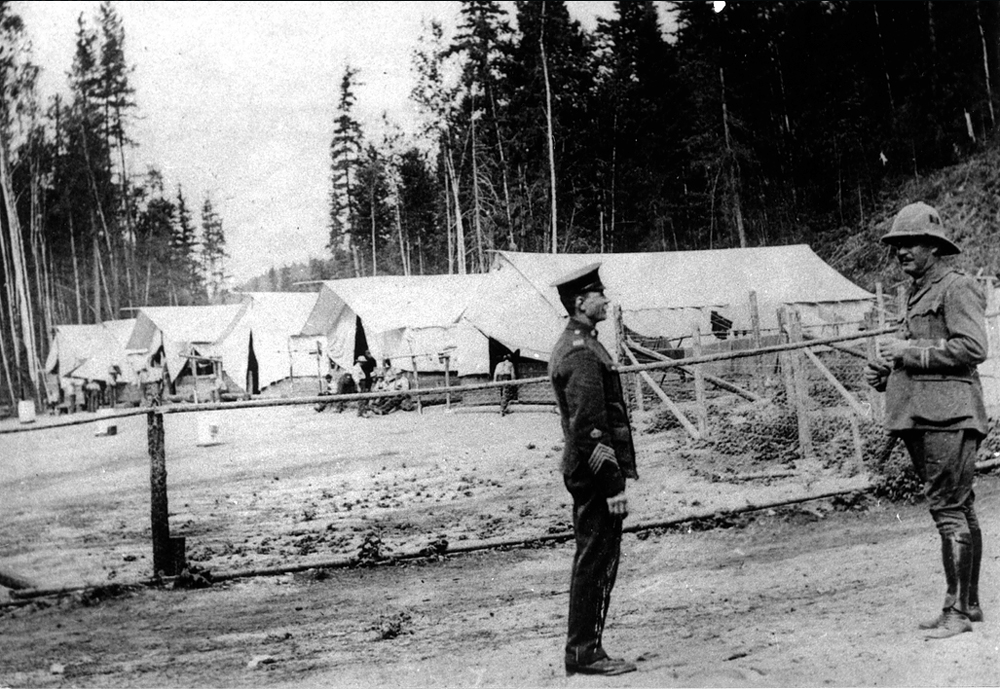

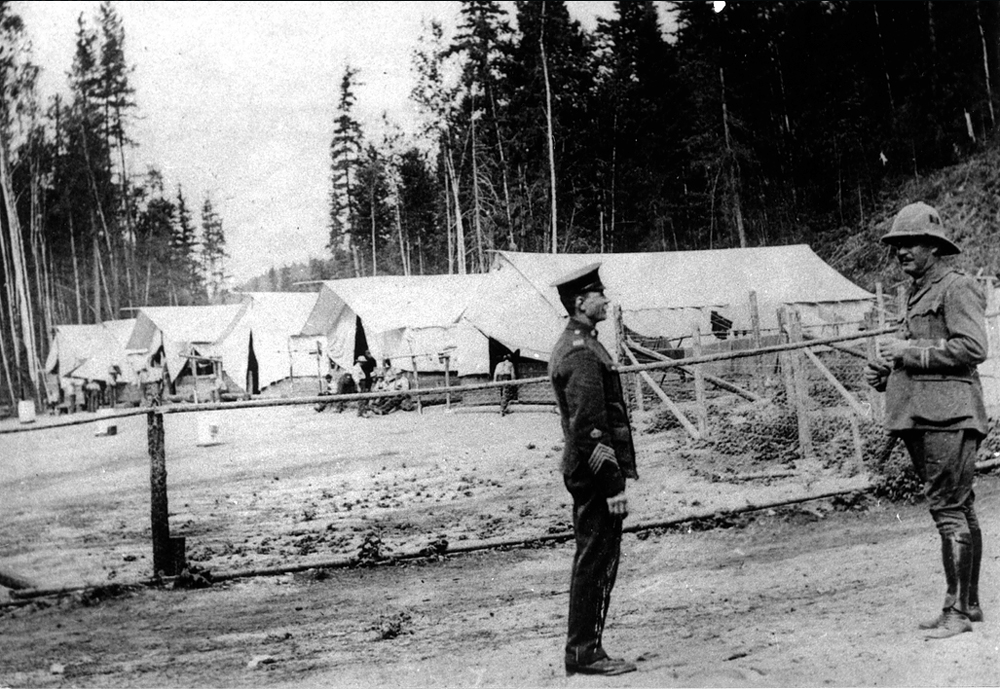

A guard and an officer in a colonial style pith helmet converse by the Revelstoke camp.

A guard and an officer in a colonial style pith helmet converse by the Revelstoke camp.

Work soon began on clearing the road right-of-way, and for the first month, everything appeared to be going well. According to Supervising engineer J. M. Wardle, the project was proceeding according to schedule, "A good showing for the time left should be made, as the aliens up to the present time have worked well."1

This was not to last. The prisoners were pressed to work harder to complete as much work as possible before winter set in, and they began to protest the rough conditions and poor treatment. Blacksmiths refused to dress tools, and road crews adamantly refused to leave camp for the jobsite on several occasions.

Internees working on the road. All the work had to be done by hand. The roughness of the terrain and size of the trees gives a sense of the challenge they faced.

Internees working on the road. All the work had to be done by hand. The roughness of the terrain and size of the trees gives a sense of the challenge they faced.

While work stoppages slowed the work, the rapidly deteriorating weather brought everything to a screeching halt. Unsurprisingly, the area of a future ski-resort was subject to heavy snowfalls that kept the internees shovelling rather than working pick-axes on the iron-hard rock. Finally, the camp's water supply failed.

It had been only a month since the camp had opened, and now, with winter bearing down on them, the camp staff and internees beat a hasty retreat down the mountain. The poor men were sent to Field, BC for the winter, which would prove to be an even worse experience.

While the move was necessary, business people in Revelstoke were bitter at the transfer. They feared that the internees would never return and the road would not be completed. Although representatives in Revelstoke tried to secure internee labour the following year, their initial fears were confirmed and internees never returned to Revelstoke.

Local business owners thought that a road to the summit of Mount Revelstoke would attract visitors who would ultimately spend money at the town's businesses. Harkin and Major General Otter agreed and construction began on the log buildings which would house the unwilling workforce.

Despite Otter's agreement and blessing for the new camp, he was disappointed when he came to Revelstoke to inspect the construction. The site was cramped, and the location was less than ideal. However, much of the work was already done, and crowding at the Brandon camp put pressure on the new camp to be completed quickly. He gave it approval and the first batch of 50 internees arrived in September. Another 150 prisoners arrived shortly after, bringing the total prisoner population to 200 along with 100 armed guards.

Work soon began on clearing the road right-of-way, and for the first month, everything appeared to be going well. According to Supervising engineer J. M. Wardle, the project was proceeding according to schedule, "A good showing for the time left should be made, as the aliens up to the present time have worked well."1

This was not to last. The prisoners were pressed to work harder to complete as much work as possible before winter set in, and they began to protest the rough conditions and poor treatment. Blacksmiths refused to dress tools, and road crews adamantly refused to leave camp for the jobsite on several occasions.

While work stoppages slowed the work, the rapidly deteriorating weather brought everything to a screeching halt. Unsurprisingly, the area of a future ski-resort was subject to heavy snowfalls that kept the internees shovelling rather than working pick-axes on the iron-hard rock. Finally, the camp's water supply failed.

It had been only a month since the camp had opened, and now, with winter bearing down on them, the camp staff and internees beat a hasty retreat down the mountain. The poor men were sent to Field, BC for the winter, which would prove to be an even worse experience.

While the move was necessary, business people in Revelstoke were bitter at the transfer. They feared that the internees would never return and the road would not be completed. Although representatives in Revelstoke tried to secure internee labour the following year, their initial fears were confirmed and internees never returned to Revelstoke.