Nanaimo's WWI Internment Camp

Near this spot, just by the intersection of Stewart Ave and Townsite Road, there was an internment camp during the First World War. It was located in the old provincial jail building that is no longer extant, and opened on September 20, 1914. Those incarcerated were called 'enemy aliens', that is people living in Canada originating from Germany and Austria-Hungary. While the government claimed they were imprisoned to protect national security, in most cases people were interned for reasons that were either completely arbitrary or jealously cynical.

A barbed wire fence some 14-feet tall was erected around the jail building. Guards were billeted at the nearby Agricultural Hall and oversaw the internees as they were put to work planting trees around downtown Nanaimo.

Ultimately over 100 internees were kept here, including some of the wives and children of the male internees. The camp stayed open until September 1915, when it was closed and its prisoners transferred to the primary internment camp in Vernon in the province's interior.

A barbed wire fence some 14-feet tall was erected around the jail building. Guards were billeted at the nearby Agricultural Hall and oversaw the internees as they were put to work planting trees around downtown Nanaimo.

Ultimately over 100 internees were kept here, including some of the wives and children of the male internees. The camp stayed open until September 1915, when it was closed and its prisoners transferred to the primary internment camp in Vernon in the province's interior.

* * *

Internment on the Island was deeply tied to the labour politics of the coal industry and heavily influenced by the events of the Vancouver Island Coal Strike, or "Great Strike" as it was known. It was the fiercest labour dispute in the province's history. The strike lasted from 1912 right up to the outbreak of the First World War, and ended up contributing to great bitterness towards the Austro-Hungarians living and working in the region.

The strike began in September 1912 with the firing of a prominent union organizer. The firing compounded other grievances like poor safety conditions and the refusal of Canadian Collieries, the owner of the Dunsmuir mine, to recognize the union. The mines in the Nanaimo area were exceptionally deadly: the South Wellington and Extension mines averaged 4.5 times more deaths per million tonnes of coal mined than other mines in the province.1. The miners decided to strike.

Canadian Collieries refused to negotiate and instead evicted the families of striking miners from company housing. Other miners from across the region mounted solidarity strikes, and by the spring of 1913, 3,500 were striking across the region. The mining companies dug in, and began hiring non-union strikebreakers--or 'scabs'.

The majority of these strikebreakers were immigrants from China, Italy, and Austro-Hungarian Ukraine. They were paid $4 a week—a pittance compared to the $11.25 to $17.50 paid to the union miners.2 Under the arbitrary ethnic prejudices widespread in Canadian society at the time, eastern and southern Europeans like the Ukrainians and Italians were not considered part of the privileged "white" ethnicity—this category was reserved for those of western, and occasionally northern, European descent.

The immigrant labourers working as strikebreakers were largely ignorant of union politics when they were hired and had limited options for employment. A severe economic recession had caused high unemployment, especially amongst these non-white immigrants. Working for strikebreaker wages was an opportunity that many starving immigrants couldn't refuse. Within eight months, many of the mines were able to resume operations despite the strike.

Infuriated by the actions of the coal companies, strikers targeted the strikebreakers. Strikers and their supporters harassed them as they arrived in town and on their way to work. In some cases they turned to violence, forcing strikebreakers and their families from their homes in South Wellington and throwing rocks through the windows at a hotel in Ladysmith where many strikebreakers were staying.

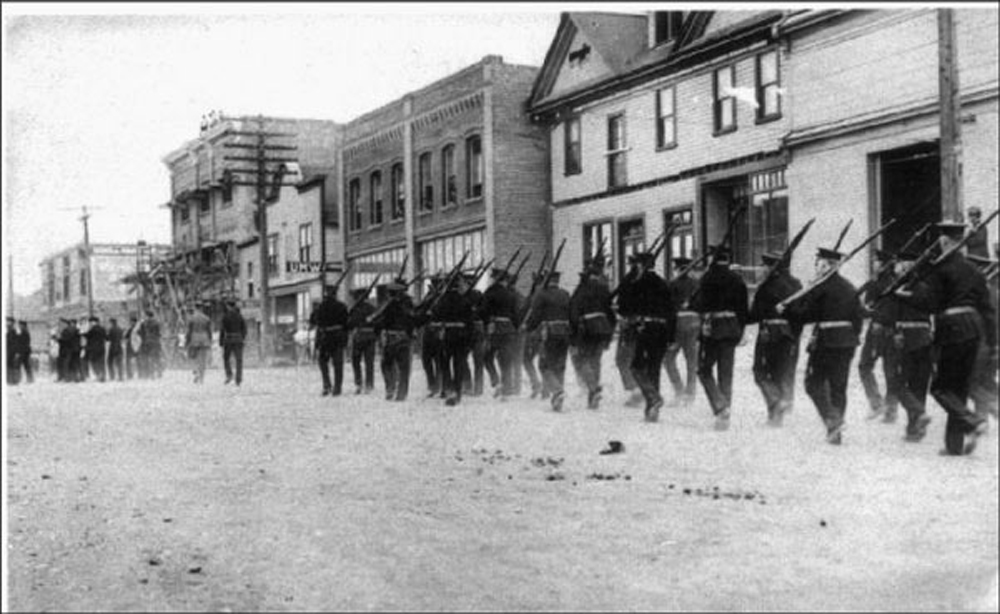

These events spurred William John Bowser, BC's acting premier and attorney general, to call in the militia in August 1913. Despite numerous arrests and the continual presence of the militia, the strike continued. The mining companies, reaping the benefits of strikebreaker labour, held firm.

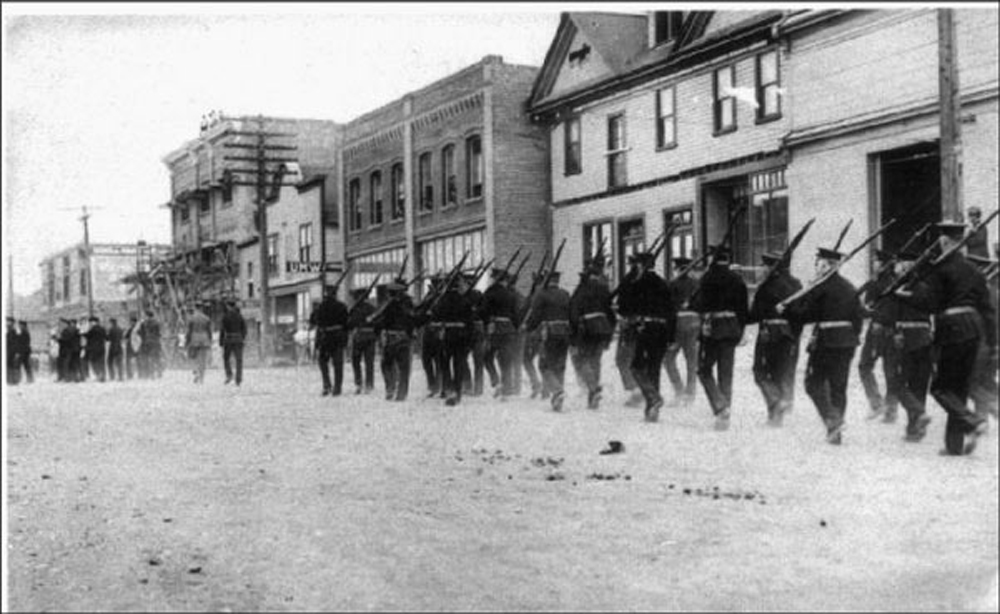

Militiamen march down the street in Ladysmith, one of the communities affected by the Vancouver Island Coal Strike.

Militiamen march down the street in Ladysmith, one of the communities affected by the Vancouver Island Coal Strike.

By July 1914, the local chapter of the United Mine Workers Union of America (UMWA) had run out of money for strike pay.

Weeks later, Canada entered the war, and the miners voted to end the strike.

Despite this vote the mine companies saw little reason to hire back the strikers, especially since the strikebreakers had returned the mines to normal production levels. The Manitoba Free Press reported: "As the mines of the district are working full force, a few of the striking miners will be able to secure employment and will be compelled to leave the city and seek work elsewhere."3

As the war got underway, suspicion increasingly fell on Austro-Hungarian immigrants, many of whom were now employed in the coal mines. Many residents of the mining towns on central Vancouver Island already resented them for contributing to the crushing of the Great Strike. Now these immigrants were also officially "enemy aliens."

The government began arresting and interning those men from Germany and Austria-Hungary that might attempt to return home and join the German and Austrian armies. An internment camp was set up for them at the Provincial Jail in Nanaimo.

The Vancouver Province reported: "The majority of the men under restraint are army reservists who endeavored to leave the country with the object of rejoining the colors of the nations with which Great Britain is at war."4 Despite some newspapers reporting that vast numbers of German and Austrian reservists in Canada were deserting to join the opposing side, there is no evidence that any Ukrainian returned home to fight for Austria-Hungary, according to Lubomur Luciuk, a professor at the Royal Military College of Canada.5

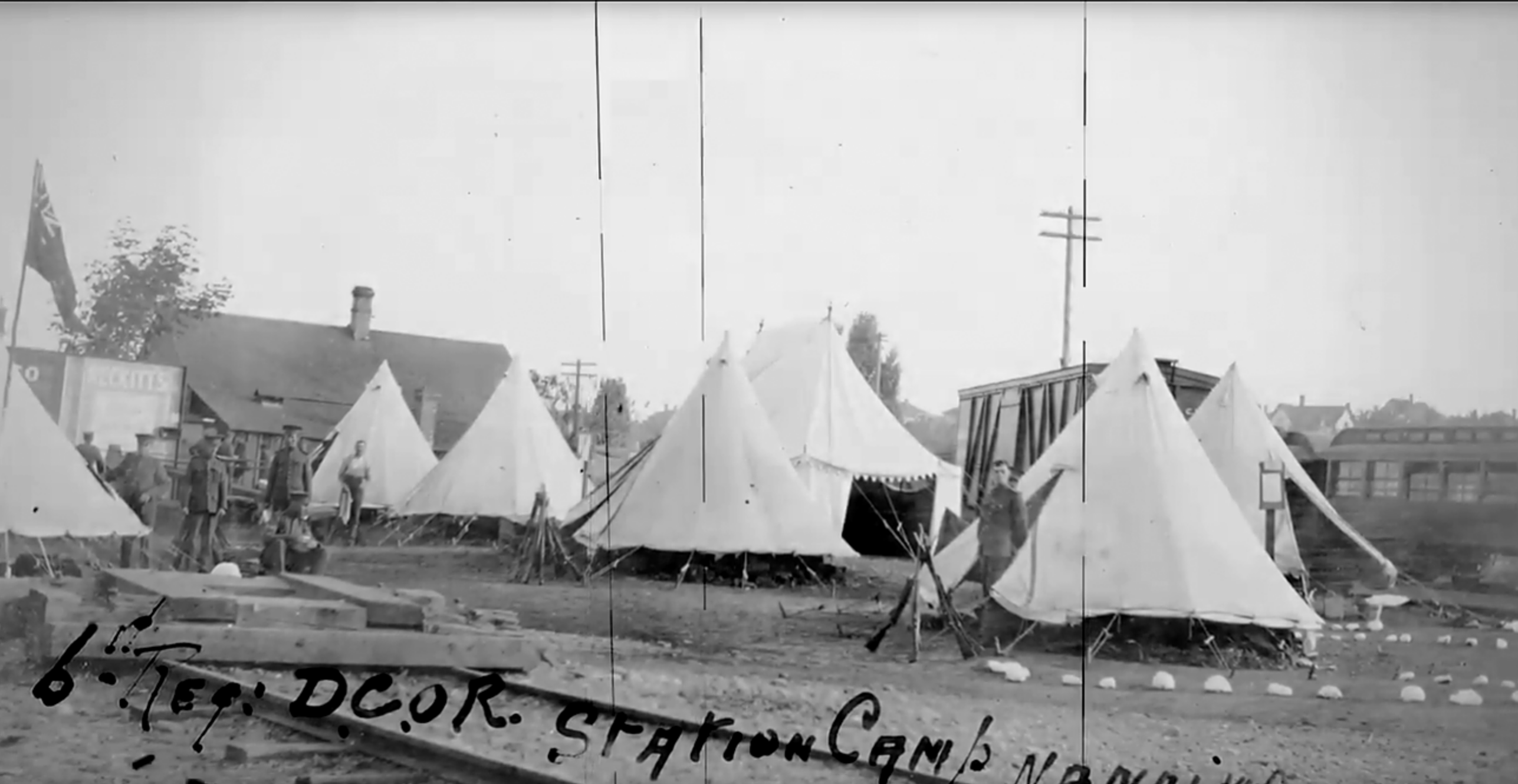

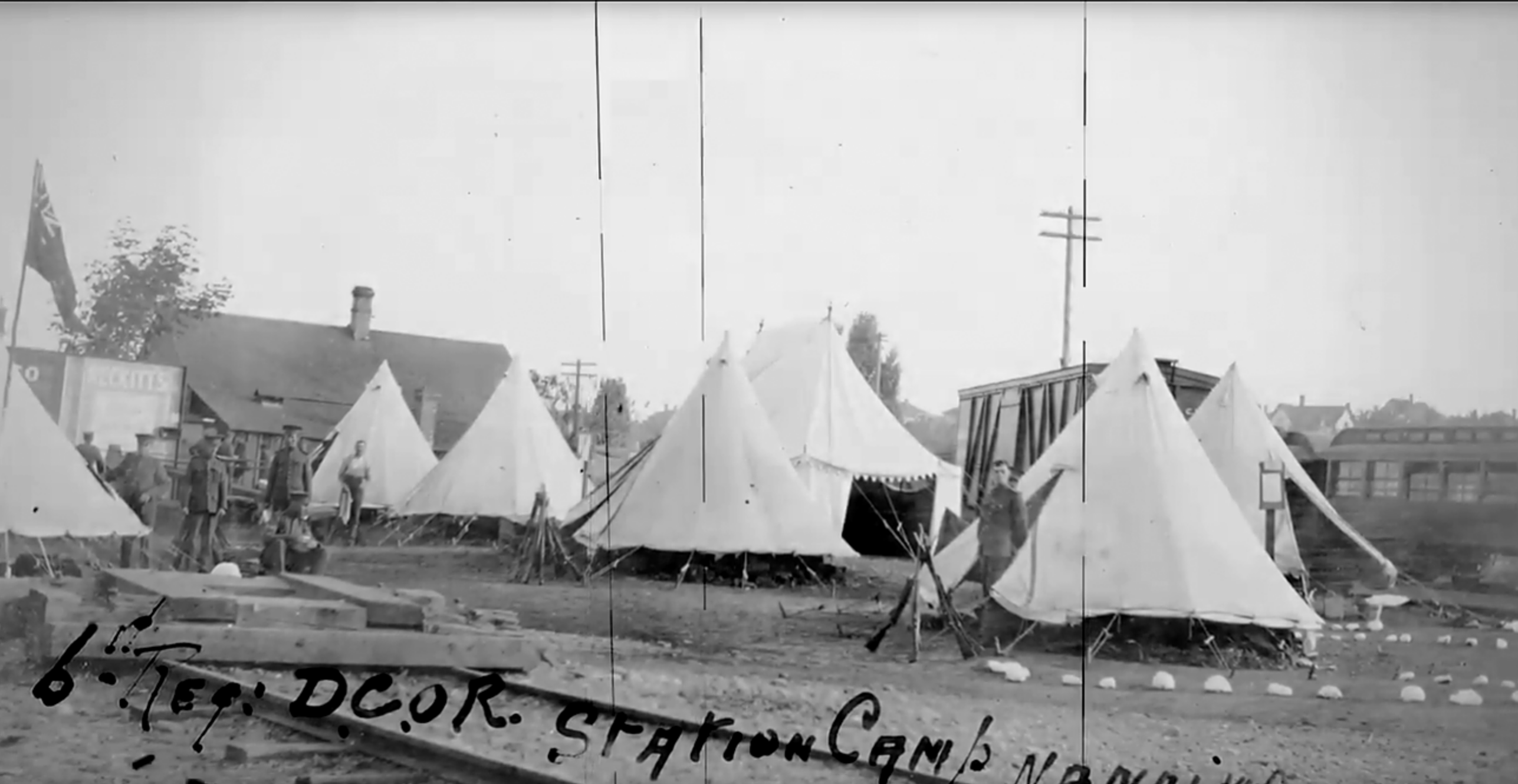

The internment camp's guards spent the summer in tents on the grounds of the Agricultural Hall.

The internment camp's guards spent the summer in tents on the grounds of the Agricultural Hall.

For the remainder of 1914, the majority of internees in Nanaimo were those who had been imprisoned under suspicion of enemy activity. The criteria for internment at Nanaimo broadened in April 1915. The Vernon News reported that the BC government had officially issued the order to intern every unemployed 'enemy alien' in British Columbia and had instructed the officers in charge of the camps to increase their capacity. According to the article, this was intended to "lessen the floating population of labourers" so that "British subjects and non-enemy aliens resident in the province will have larger opportunities for securing work than they have had in the past."6

According to Borys Sydoruk, the chair of the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation, "British Columbia was especially malicious for going after potential enemy aliens. They were actually faster at rounding people up than the federal government."7

The situation deteriorated further following the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania by a German U-Boat, with heavy loss of life, many Canadian civilians amongst them. A mob of 2,000 took to the streets of Victoria and attacked German-owned businesses, causing upwards of $25,000 in property damage. Shortly after, reports circulated that military officials had rounded up 115 Austro-Hungarian and German miners for internment on Vancouver Island, and that hundreds more who were still employed in the mines would be interned as soon as space could be made for them. Newspapers reported that Acting-Premier Bowser stated that the government hoped that "every effort will be made to fill places vacated by Germans and Austrians from deserving unemployed, particularly those men, heads of families who have been out of work a long time, and who have been in receipt of relief from the government."8

Encouraged by these moves, white coal miners across BC went on strike to protest the presence of 'enemy aliens' working alongside them. Bowser, desperate to keep wartime coal production high, wasted no time in escalating internment operations to accommodate growing numbers of internees. By August, there were six internment camps in BC holding over 1,000 internees.

By this time, the nature of the internment camps had shifted from confinement to labour. Since the Nanaimo camp was contained in a former prison, it had a limited capacity, and in September of 1915, the camp was closed and its prisoners transferred to Vernon.

The camp at Nanaimo had been overcrowded for months, and the establishment of more camps across the province allowed the government to put more internees to work on infrastructure and industry projects. After the camp's closure, 'enemy aliens' from Vancouver Island continued to be interned, but they were sent to the interior.

Karl Swartz, the principal of Nanaimo's high school, was arrested while working in his vegetable garden in 1916. He was taken to Vernon, where his family joined him voluntarily. There weren't many women and children in the camps, but occasionally, families chose to stay together in internment, since women were left with no income or support in their husbands' absence.

Before its closure, some at the Nanaimo camp made the bold decision to try and escape. John Wolert, a German interned at the Nanaimo camp in 1915, escaped by climbing the fence but was arrested in the United States and returned to Canadian officials. While he was being transported back to the camp, he escaped again by jumping from a moving train. A guard broke his leg jumping off the train in an attempt to recover Wolert, who again made it to the United States and was again arrested by an immigration officer. However, this time he was released after some friends intervened on his behalf and demonstrated that he had previously lived in the United States and had enough money to support himself.

Carl Kastner, a former iron-worker, was also able to escape through a hole in the roof. The newspapers never confirmed if he was ever recaptured.

While these two men may have been fortunate enough to escape internment, others never saw freedom again. Records indicate that 18 prisoners died in B.C.’s camps. However, the real number may have been higher than reported. A recent Ground Penetrating Radar survey conducted by archaeologist Sarah Beaulieu found 7 unrecorded graves at the Morrissey camp cemetery.

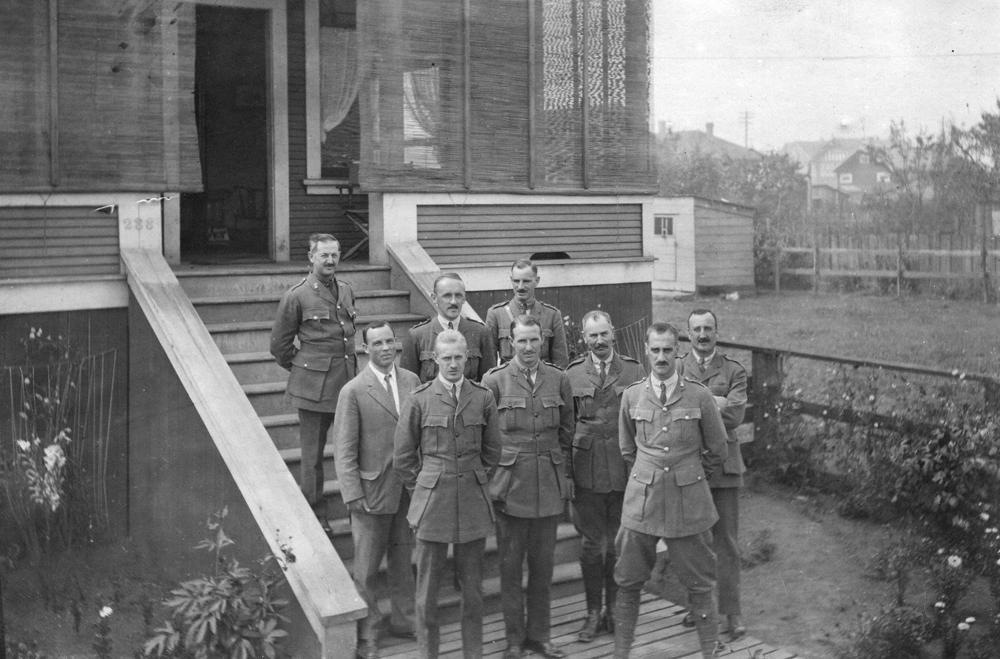

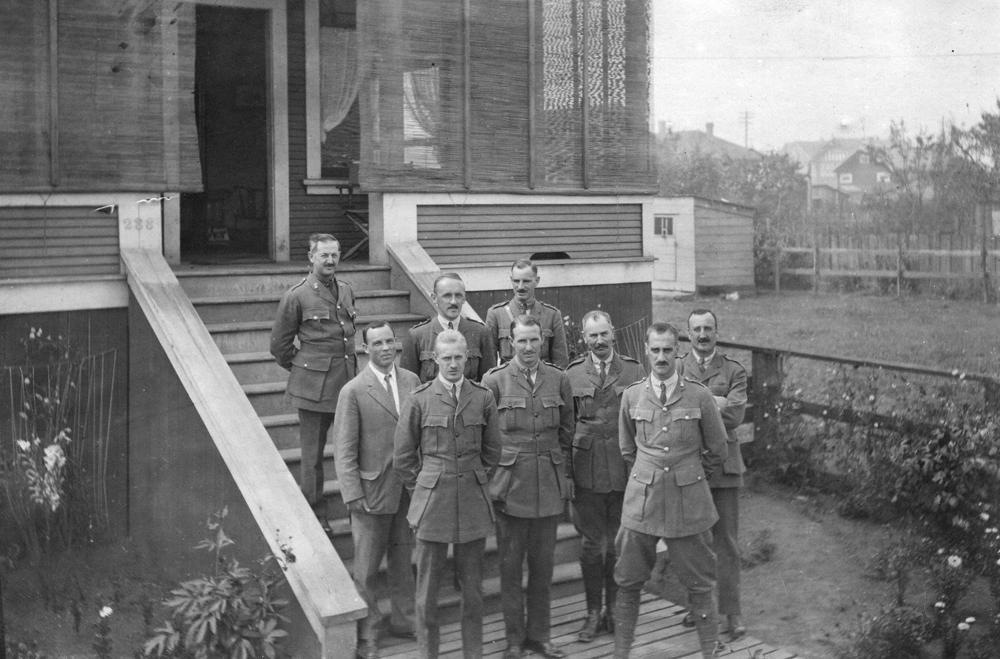

Guards at the Nanaimo internment camp pose for a photograph.

Guards at the Nanaimo internment camp pose for a photograph.

As the war dragged on and more men left their homes and jobs to serve in Europe, Canada went from labour surplus to labour shortage. In May 1916, the Canadian government released approximately 1,000 internees across the country to work in the coal mining and pulp industries so that, "instead of continuing to be an expense to the community they will contribute henceforth to its industrial warfare."9

As Austro-Hungarians and Germans had originally been imprisoned to appease white coal miners, this news was predictably not well received in British Columbia. An article published in September questioned why internees were being given work when local communities were opposed to this. The article states, "If it is desired to remove the cost of maintaining them from the shoulders of the public, they should be set to work on roads as British prisoners are in Germany and only a living allowance paid them".10

Later that month, the Nanaimo City Council read a resolution protesting the release of internees to work in the mines because there were many "British subjects" to fill the positions. The resolution demanded that all "enemy aliens" should be strictly interned throughout the duration of the war. While some on the council agreed with this premise, some were opposed. According to the Vancouver World, Alderman Goulet argued that those imprisoned in camp were, "Sitting in the lap of indolence and luxury… when they might be more cheerfully occupied in breaking rocks on roadways or some similar form of light exercise." While there are many words that can be used to describe the grim conditions in the internment camps, "luxurious" has never been one of them.

Goulet also suggested that if the internees were to work in the mines, they should be put together in one mine, "where if they felt disposed to to exercise their Hunnish ideas of kultur, and blow something up, they might explode a charge that would give them a good start for the happy hunting grounds, and 'be a good riddance too."11

Despite the City's resolution, the internees continued to labour in the mines for only 25 cents a day. In early 1917, officials finally responded to the complaints and launched an investigation into "enemy alien" labour in the mines. By February, 22 internees were removed from the mines at Cumberland and Nanaimo and returned to the camps.

As the war drew to a close, the government shut down camps across Canada and consolidated the remaining prisoners into the few remaining camps or else released them on parole. Yet while the war abroad had ended, prejudice at home had not. Labour conflict was still high, and many employers refused to hire former enemy aliens. Returning war veterans, embittered by their experiences fighting Germans and Austrians in Europe, intimidated and destroyed the properties of some of those that lived in Canada. The anti-socialist Red Scare began, and the Canadian public viewed Eastern Europeans especially, as a communist threat.

As a result the camps at Vernon, BC, and Kapuskasing, Ontario, still remained in operation until as late as 1920. This hostile climate kept many Eastern Europeans in Canada and on Vancouver Island "In fear of the barbed wire fence" for many years after the war.

The strike began in September 1912 with the firing of a prominent union organizer. The firing compounded other grievances like poor safety conditions and the refusal of Canadian Collieries, the owner of the Dunsmuir mine, to recognize the union. The mines in the Nanaimo area were exceptionally deadly: the South Wellington and Extension mines averaged 4.5 times more deaths per million tonnes of coal mined than other mines in the province.1. The miners decided to strike.

Canadian Collieries refused to negotiate and instead evicted the families of striking miners from company housing. Other miners from across the region mounted solidarity strikes, and by the spring of 1913, 3,500 were striking across the region. The mining companies dug in, and began hiring non-union strikebreakers--or 'scabs'.

The majority of these strikebreakers were immigrants from China, Italy, and Austro-Hungarian Ukraine. They were paid $4 a week—a pittance compared to the $11.25 to $17.50 paid to the union miners.2 Under the arbitrary ethnic prejudices widespread in Canadian society at the time, eastern and southern Europeans like the Ukrainians and Italians were not considered part of the privileged "white" ethnicity—this category was reserved for those of western, and occasionally northern, European descent.

The immigrant labourers working as strikebreakers were largely ignorant of union politics when they were hired and had limited options for employment. A severe economic recession had caused high unemployment, especially amongst these non-white immigrants. Working for strikebreaker wages was an opportunity that many starving immigrants couldn't refuse. Within eight months, many of the mines were able to resume operations despite the strike.

Infuriated by the actions of the coal companies, strikers targeted the strikebreakers. Strikers and their supporters harassed them as they arrived in town and on their way to work. In some cases they turned to violence, forcing strikebreakers and their families from their homes in South Wellington and throwing rocks through the windows at a hotel in Ladysmith where many strikebreakers were staying.

These events spurred William John Bowser, BC's acting premier and attorney general, to call in the militia in August 1913. Despite numerous arrests and the continual presence of the militia, the strike continued. The mining companies, reaping the benefits of strikebreaker labour, held firm.

By July 1914, the local chapter of the United Mine Workers Union of America (UMWA) had run out of money for strike pay.

Weeks later, Canada entered the war, and the miners voted to end the strike.

Despite this vote the mine companies saw little reason to hire back the strikers, especially since the strikebreakers had returned the mines to normal production levels. The Manitoba Free Press reported: "As the mines of the district are working full force, a few of the striking miners will be able to secure employment and will be compelled to leave the city and seek work elsewhere."3

As the war got underway, suspicion increasingly fell on Austro-Hungarian immigrants, many of whom were now employed in the coal mines. Many residents of the mining towns on central Vancouver Island already resented them for contributing to the crushing of the Great Strike. Now these immigrants were also officially "enemy aliens."

The government began arresting and interning those men from Germany and Austria-Hungary that might attempt to return home and join the German and Austrian armies. An internment camp was set up for them at the Provincial Jail in Nanaimo.

The Vancouver Province reported: "The majority of the men under restraint are army reservists who endeavored to leave the country with the object of rejoining the colors of the nations with which Great Britain is at war."4 Despite some newspapers reporting that vast numbers of German and Austrian reservists in Canada were deserting to join the opposing side, there is no evidence that any Ukrainian returned home to fight for Austria-Hungary, according to Lubomur Luciuk, a professor at the Royal Military College of Canada.5

For the remainder of 1914, the majority of internees in Nanaimo were those who had been imprisoned under suspicion of enemy activity. The criteria for internment at Nanaimo broadened in April 1915. The Vernon News reported that the BC government had officially issued the order to intern every unemployed 'enemy alien' in British Columbia and had instructed the officers in charge of the camps to increase their capacity. According to the article, this was intended to "lessen the floating population of labourers" so that "British subjects and non-enemy aliens resident in the province will have larger opportunities for securing work than they have had in the past."6

According to Borys Sydoruk, the chair of the Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Foundation, "British Columbia was especially malicious for going after potential enemy aliens. They were actually faster at rounding people up than the federal government."7

The situation deteriorated further following the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania by a German U-Boat, with heavy loss of life, many Canadian civilians amongst them. A mob of 2,000 took to the streets of Victoria and attacked German-owned businesses, causing upwards of $25,000 in property damage. Shortly after, reports circulated that military officials had rounded up 115 Austro-Hungarian and German miners for internment on Vancouver Island, and that hundreds more who were still employed in the mines would be interned as soon as space could be made for them. Newspapers reported that Acting-Premier Bowser stated that the government hoped that "every effort will be made to fill places vacated by Germans and Austrians from deserving unemployed, particularly those men, heads of families who have been out of work a long time, and who have been in receipt of relief from the government."8

Encouraged by these moves, white coal miners across BC went on strike to protest the presence of 'enemy aliens' working alongside them. Bowser, desperate to keep wartime coal production high, wasted no time in escalating internment operations to accommodate growing numbers of internees. By August, there were six internment camps in BC holding over 1,000 internees.

By this time, the nature of the internment camps had shifted from confinement to labour. Since the Nanaimo camp was contained in a former prison, it had a limited capacity, and in September of 1915, the camp was closed and its prisoners transferred to Vernon.

The camp at Nanaimo had been overcrowded for months, and the establishment of more camps across the province allowed the government to put more internees to work on infrastructure and industry projects. After the camp's closure, 'enemy aliens' from Vancouver Island continued to be interned, but they were sent to the interior.

Karl Swartz, the principal of Nanaimo's high school, was arrested while working in his vegetable garden in 1916. He was taken to Vernon, where his family joined him voluntarily. There weren't many women and children in the camps, but occasionally, families chose to stay together in internment, since women were left with no income or support in their husbands' absence.

Before its closure, some at the Nanaimo camp made the bold decision to try and escape. John Wolert, a German interned at the Nanaimo camp in 1915, escaped by climbing the fence but was arrested in the United States and returned to Canadian officials. While he was being transported back to the camp, he escaped again by jumping from a moving train. A guard broke his leg jumping off the train in an attempt to recover Wolert, who again made it to the United States and was again arrested by an immigration officer. However, this time he was released after some friends intervened on his behalf and demonstrated that he had previously lived in the United States and had enough money to support himself.

Carl Kastner, a former iron-worker, was also able to escape through a hole in the roof. The newspapers never confirmed if he was ever recaptured.

While these two men may have been fortunate enough to escape internment, others never saw freedom again. Records indicate that 18 prisoners died in B.C.’s camps. However, the real number may have been higher than reported. A recent Ground Penetrating Radar survey conducted by archaeologist Sarah Beaulieu found 7 unrecorded graves at the Morrissey camp cemetery.

As the war dragged on and more men left their homes and jobs to serve in Europe, Canada went from labour surplus to labour shortage. In May 1916, the Canadian government released approximately 1,000 internees across the country to work in the coal mining and pulp industries so that, "instead of continuing to be an expense to the community they will contribute henceforth to its industrial warfare."9

As Austro-Hungarians and Germans had originally been imprisoned to appease white coal miners, this news was predictably not well received in British Columbia. An article published in September questioned why internees were being given work when local communities were opposed to this. The article states, "If it is desired to remove the cost of maintaining them from the shoulders of the public, they should be set to work on roads as British prisoners are in Germany and only a living allowance paid them".10

Later that month, the Nanaimo City Council read a resolution protesting the release of internees to work in the mines because there were many "British subjects" to fill the positions. The resolution demanded that all "enemy aliens" should be strictly interned throughout the duration of the war. While some on the council agreed with this premise, some were opposed. According to the Vancouver World, Alderman Goulet argued that those imprisoned in camp were, "Sitting in the lap of indolence and luxury… when they might be more cheerfully occupied in breaking rocks on roadways or some similar form of light exercise." While there are many words that can be used to describe the grim conditions in the internment camps, "luxurious" has never been one of them.

Goulet also suggested that if the internees were to work in the mines, they should be put together in one mine, "where if they felt disposed to to exercise their Hunnish ideas of kultur, and blow something up, they might explode a charge that would give them a good start for the happy hunting grounds, and 'be a good riddance too."11

Despite the City's resolution, the internees continued to labour in the mines for only 25 cents a day. In early 1917, officials finally responded to the complaints and launched an investigation into "enemy alien" labour in the mines. By February, 22 internees were removed from the mines at Cumberland and Nanaimo and returned to the camps.

As the war drew to a close, the government shut down camps across Canada and consolidated the remaining prisoners into the few remaining camps or else released them on parole. Yet while the war abroad had ended, prejudice at home had not. Labour conflict was still high, and many employers refused to hire former enemy aliens. Returning war veterans, embittered by their experiences fighting Germans and Austrians in Europe, intimidated and destroyed the properties of some of those that lived in Canada. The anti-socialist Red Scare began, and the Canadian public viewed Eastern Europeans especially, as a communist threat.

As a result the camps at Vernon, BC, and Kapuskasing, Ontario, still remained in operation until as late as 1920. This hostile climate kept many Eastern Europeans in Canada and on Vancouver Island "In fear of the barbed wire fence" for many years after the war.