Walking Tour

Enslaved in a 'Glorious Playground'

Internment in Jasper in 1916

Andrew Farris

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

Just a short distance from the Jasper townsite off Old Fort Point Road, there is a small, partially forested area criss-crossed with trails that has the feel of a campground. Alongside the turquoise waters of the Athabasca River, and surrounded by breathtaking Rocky Mountain vistas, this is an idyllic spot for a walk, a picnic, or just quiet contemplation.

This was the location of an internment camp for so-called 'enemy aliens' in 1916. The men interned here were forced to do back-breaking physical labour for long hours in sub-zero temperatures while wearing tattered rags. They were fed so poorly that many complained they were near the point of starvation. They were beaten and abused by the guards, and shackled and stuffed in solitary confinement cells for weeks at a time if they refused to work.

The men imprisoned here had immigrated to Canada from countries that Canada went to war with during the First World War. They were not spies, saboteurs, or traitors. The reason for their internment was much more banal: In 1914, many employers began firing their employees who were born in enemy countries, creating a very serious homelessness problem. The government of Canada responded by criminalizing homelessness and poverty amongst people born in enemy nations, legally reclassifying them as 'enemy aliens', and stripping away almost all of their civil rights.

Destitute and helpless, thousands of central and eastern European immigrants (over half were Ukrainian) were arrested and sent to internment camps. Camps like this were a way to get destitute immigrants away from the vindictive eyes of the public, and a means of harnessing this newly available pool of cheap, easily abused labour.

In this tour we will examine the development of Jasper as a National Park, and how this internment camp came to be on this spot. We will hear of the experiences of the internees, the work they were forced to do here, and learn about the guards who reluctantly watched over them. We will see how the internees resisted their captors and launched a series of strikes that were so successful they resulted in the closure of this camp and the provisional release of almost all of its captives within six months of the camp's opening.

This project has been made possible by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund.

1. Jasper

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

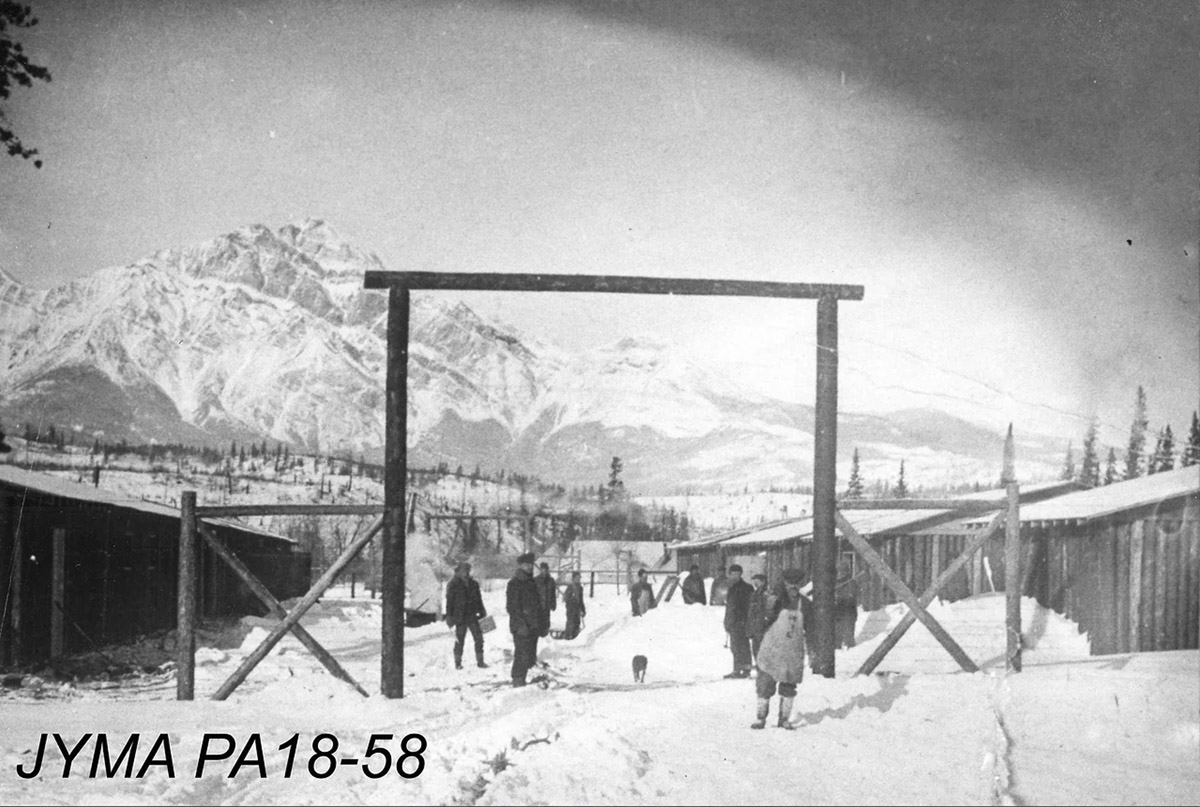

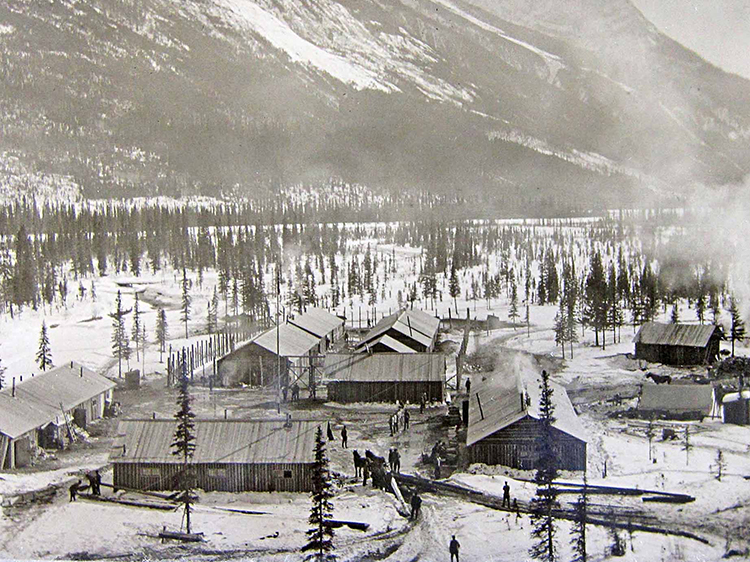

This photo shows the entrance of the Jasper internment camp which was located here from February to August 1916. The camp was one of a number of forced labour camps established for 'enemy aliens' in Canada's national parks. The internees were primarily set to work building roads, but also used for whatever other tasks the recently established Dominion Parks Branch could devise for them.

Jasper National Park was established in 1907 after the Grand Trunk Pacific railway was planned to run through the Yellowhead Pass. By the time the First World War started, only minimal park infrastructure had been built, and Jasper's few inhabitants were thrilled for the opportunity to have internee labour help improve the park and the little town at its heart.

* * *

Much later on, the park was established with the intention it be a "wilderness playground" for tourists. The area's long-standing Metis inhabitants were classified as squatters and evicted. In 1911 the Grand Trunk Pacific railway was completed through the park with a railway station at the town that became known as Jasper. That same year the park came under the jurisdiction of the newly-formed Dominion Parks Branch—the first national parks service in the world.

By the time the First World War broke out in 1914, Jasper boasted some hotels and basic infrastructure, but it had seen less development than Banff National Park to the south. In addition, the war saw the Dominion Parks Branch budget cut in half, leaving little money to fulfill the ambitious development plans of James B. Harkin, the branch's first commissioner.

2. Austro-Hungarians in Canada

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

This wintertime photo of internees under guard at the Jasper camp must have been taken sometime soon after its opening in February 1916.

The internees had been classified as 'enemy aliens' for being born in countries that Canada was at war with, including Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire. During the war some 8,579 enemy aliens were sent to internment camps like this one, and over 3/4 of the total came from the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire. Almost all the men interned at this camp came from the Habsburg dual-monarchy including Ukrainians (the majority), Poles, Croats, Serbs, Italians, Slovakians, Slovenes, Czechs, and Hungarians, to name just a few.

In the decades before the war, these immigrants were discriminated against by the British-dominated Canadian society. Their treatment as a racially inferior 'other' laid the groundwork for their wartime internment in forced labour in camps like this one.

* * *

Nevertheless Canada was desperate for settlers and the Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier actively sought out immigrants from these regions. These efforts bore fruit and hundreds of thousands of immigrants came from the territories of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, comprising a dozen major nationalities (all of which have their own nation-state today).

By far the most numerous of these people were Ukrainians who came from the Austrian provinces of Galicia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia—today's western Ukraine. At the time the Ukrainians were known in Canada by many names, including Ruthenian, Rusyn, Galician, and even Greek Catholic. Many settled on prairie homesteads in Ukrainian bloc settlements where they could maintain their language, culture, and traditions. To wider Anglo-Canadian society these people were seen as unsophisticated and backwards, but on their bloc settlements they were out of sight and out of mind. However many young Ukrainian men also took jobs at mines, factories, forestry camps, and on the railways. These men—often illiterate and speaking little English—were treated with contempt by the Anglo-Canadian majority, who saw them as "scarcely citizens," regardless of whether they had received Canadian citizenship.

As E.B. Mitchell, an English visitor to Canada wrote, "to a Westerner, a Galician workman was little better than the despised Chinaman."1

3. Interning the Destitute

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

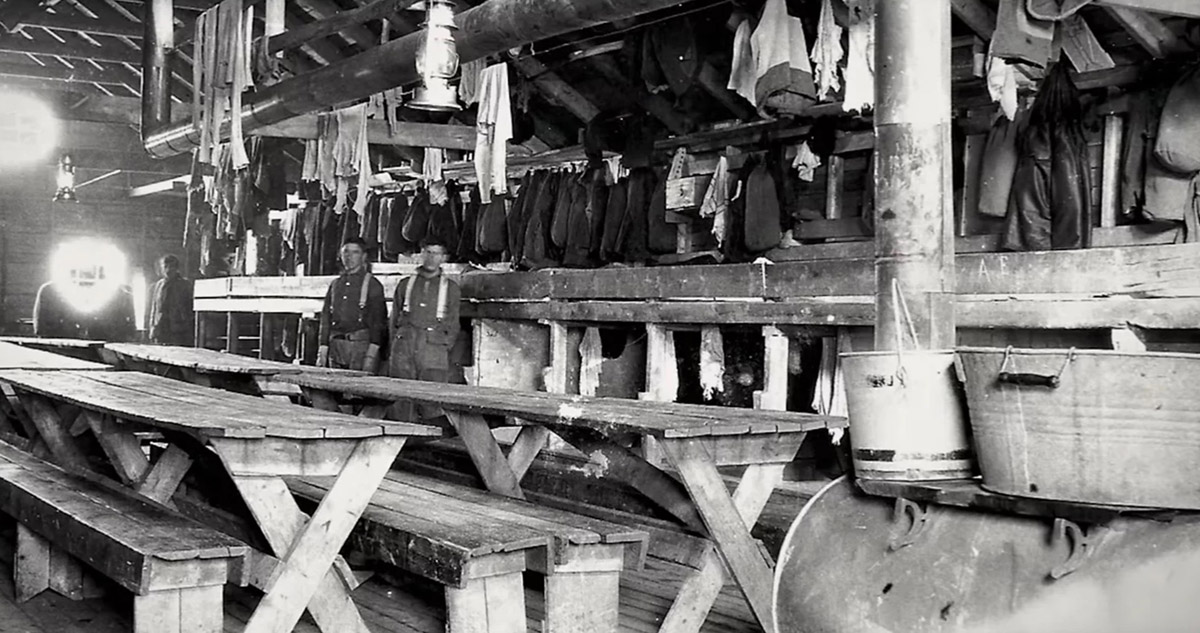

In this photo we can see internees chopping wood and clearing forest in the dead of winter.

The War Measures Act of August 1914 created a legal framework for interning these people and making them do forced labour. In almost all cases they were not interned on security grounds: Very few of them felt any allegiance to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most thought of it as a hated oppressor that they had come to Canada to leave behind.

There is little evidence that government policymakers and police officials ever regarded these 'enemy aliens' as a threat to Canada's security. An editorial in the Winnipeg Free Press wrote: "there has never at any time been any question as to the loyalty of the majority of Slav settlers. They will be faithful sons of their adopted country."1

This didn't matter because those "Slav settlers"—now enemy aliens—were competing with other workers for scarce jobs in Canada's recession-wracked economy. Once interned they could also be forced to work on jobs nobody wanted in conditions that no free workers would voluntarily agree to.

* * *

The sweeping War Measures Act included many provisions, such as the effective suspension of parliamentary democracy. It also severely curtailed the rights of enemy aliens, forcing them to comply with a large number of onerous and humiliating restrictions. These included a prohibition from leaving the country, a requirement to register with the government and then report monthly to a parole officer, and a threat of internment for any minor infraction or failure to produce their enemy alien papers upon request.

Since many employers were firing all their enemy alien employees and leaving them homeless and destitute, the government also made being homeless and destitute a crime for enemy aliens.

The government told itself it wasn't a punishment, but rather an act of charity. As the justice minister would later say:

Quite a number of them were interned more largely under the inspiration of the sentiment of compassion, if I may use the expression, than because of hostility. At that time, when the labour market was glutted, and there was a natural disposition to give the preference in the matter of employment to our own people, thousands of these aliens were starving in some of our cities... In many instances we interned these people because we felt that, saying to them 'You shall not leave the country,' we were not entitled to say, 'You shall starve within the country.'... We found that the sentiment of every man who came into contact with the Austrian who was interned was that he was absolutely not dangerous.3

Due to diplomatic complaints from the German government about the treatment of their interned countrymen, German internees were not sent to forced labour camps like this one. Coerced labour from prisoners of war (which the interned civilian immigrants were officially classified as) was a violation of international law. The Austro-Hungarian government on the other hand did not register diplomatic complaints about the forced labour of their subject nationalities. Therefore the Canadian government felt it could get away with violating the rights of Austro-Hungarians without arousing the ire of anyone whose opinion mattered.

In the end the vast majority of those sent to the forced labour camps were homeless and destitute Ukrainians and other subject Austro-Hungarian nationalities.

4. The Park Plans

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

Here we see a number of internees sitting for a photo under the watchful eye of several guards with bayonets fixed on their rifles. Behind them you can see one of the breathtaking mountain vistas that Jasper National Park is internationally renowned for. The Dominion Parks Branch and Jasper's inhabitants were eager to benefit from the work that the Austro-Hungarian enemy aliens would be forced to do.

As the Edmonton Journal wrote: "Jasper Park will see the biggest development this year that has yet been undertaken, and its fulfillment will render the park much more attractive."1

* * *

His proposal was approved in 1915, and by that July the first park camp had opened near Banff. In the shadow of Castle Mountain the internees were put to work building the road to Lake Louise. From the outset the Banff camp was plagued by incompetent leadership, abusive guards, appalling conditions, and frequent escapes. Harkin was nevertheless encouraged by the initial results, and had forced labour camps set up at the Yoho and Mount Revelstoke parks.

In 1916 a camp was planned for Jasper. The Edmonton Journal was giddy about the possibilities: "Life at the camp is not one continuous round of sightseeing for the prisoners… The amount of work to be accomplished is only limited by the duration of the war."3

The labour of the enemy aliens would create wonderful opportunities for expanded tourism, especially the road they were expected to build to Maligne Lake. The Brandon Daily Sun wrote:

"The motor road to this lake will be one of the finest in America. With German labour to build the road, the government only need to supply teams, tools and foremen… tourists from the United States have flocked to Jasper park. About ninety per cent of the people who have enjoyed the beauties of the National park are from across the border. The hunting is especially fine in Jasper."4

5. The Camp Opens

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

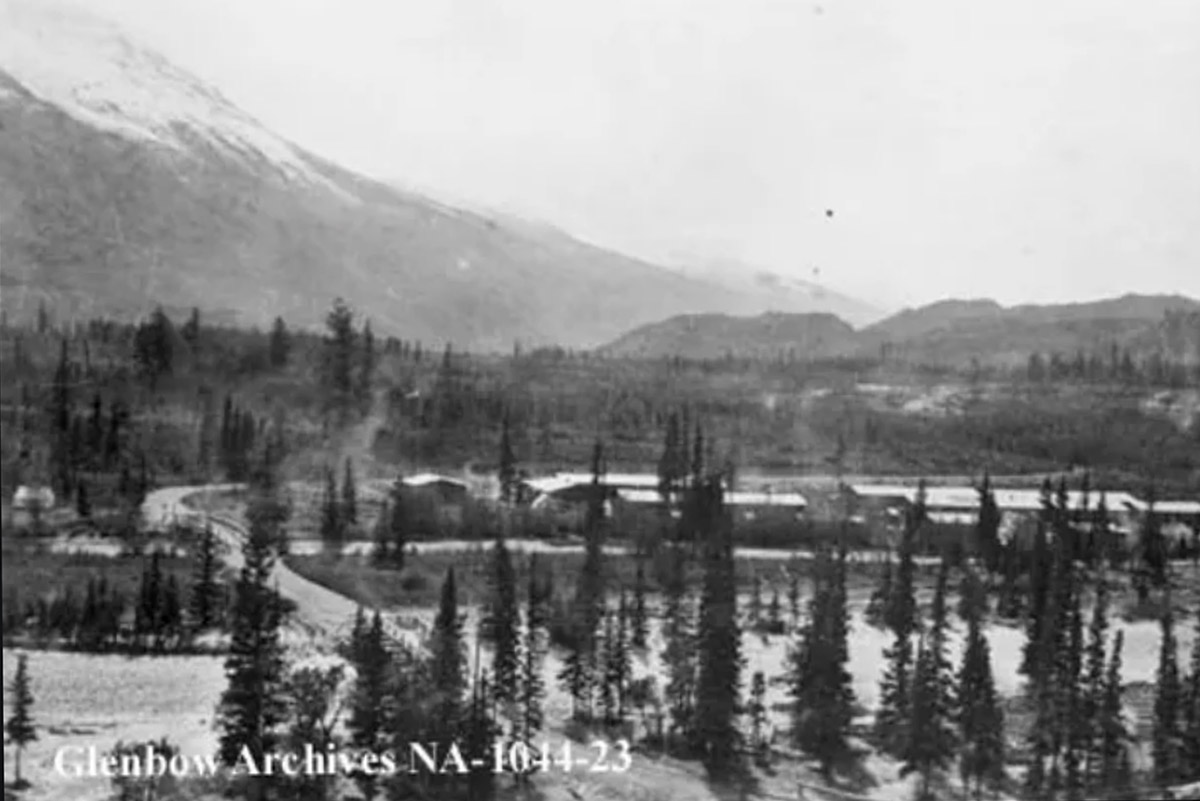

In this photo we see internees stacking firewood as they are clearing ground for the camp. An October 1915 article in the Edmonton Journal describes the plan for the Jasper camp:

"It is proposed to quarter the prisoners in huts which will be constructed by them, with the aid of soldiers. These will be warmly built and the food and accommodation will be up to the best standard… they will each receive twenty-five cents a day, which is the pay of a German soldier on active service. International law requires this to be made when prisoners are required to work."1

* * *

The camp opened in February 1915, and the 208 internees were set to work cutting wood, building roads and bridges, and generally improving the Jasper townsite.2 There were great expectations that the camp would hugely enlarge in size.

The opening of the camp was delayed by the disastrous experience of the Mount Revelstoke camp. That camp's site had been so poorly chosen—it lacked a clean water source and was overwhelmed by deep drifts of snow—that it had to be closed.

Only after many difficulties could Mount Revelstoke's frozen internees be sent to Jasper. When they arrived in February, they were 'required' to clear the site, and then build their own barbed wire enclosure, bunkhouses, and camp buildings—as we can see from the photos, all in subzero temperatures in deep snow.

Unfortunately this location for the Jasper camp was also "a stupid choice," as Bill Waiser writes in Park Prisoners. It quickly became apparent that it was at risk of flooding when the Athabasca swelled during the spring thaw. As a result enormous internee energy was expended building protective dykes.3

The internees were also sent to begin labouring at the nearby townsite: cutting 5,500 fence posts for Wainwright Park (now Centennial Park), repairing the Athabasca River bridge, and cutting a ditch in the frozen ground for the town's water mane.4

6. Finding Guards

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

Here we see four mustachioed guards posing for a photo in front of some tents. Most of the guards at Jasper appear to have been veterans of First World War battlefields sent home to recover from their extreme mental and physical trauma. Once they had somewhat recovered, they were assigned to "undertake the less vigorous duties at the internment camp."1

As it turned out these men had often not completely recovered and did not make particularly effective or benign guards, likely exacerbating the miseries of the internees. It's hard to tell—eyewitness accounts from both internees and guards at Jasper are rare.

Based on the experience of better-documented camps like Banff and Kapuskasing, we can surmise that being a guard at Jasper was a miserable job and a very undesirable posting. Just like the internees, they did not wish to be there. As a result they likely often took their frustrations out on the internees. At those other camps neutral diplomats visited and reported many internee complaints of beatings and bayonetings, frequent threats of being shot, weeks spent shackled in solitary confinement, and punishment diets of bread and water.

* * *

It appears that finding enough guards was always a problem. A large proportion of the contemporary newspaper articles that reference the Jasper camp are just 'help wanted' ads for guards.4 The shortage of guards typically meant they had to pull tedious 24-hour shifts watching prisoners at work, often in frigid temperatures.5 If there was an escape under their watch (and there were many) they would be severely disciplined.

One article discussing a meeting about the growing difficulties with recruitment mentioned a letter from a returned veteran doing guard duty at the Jasper camp, one Private W. J. Broomfield. Broomfield wrote that "he and other returned soldiers" were eager to "again take part in the fight for freedom." They preferred the trenches—and what they must have understood was a very high probability of death and dismemberment—to continuing guard duty in Jasper.

That same article also clearly illustrates that by early 1916 Alberta was already scraping the bottom of the barrel to find fit men to send to war. Looking around for suitable cannon fodder, the recruiting committee identified a number of eligible men working on the railways. They had refused repeated entreaties to sign up because they were well paid at their current jobs (and perhaps did not want to die). It was agreed that the recruiters would approach the railway companies and cajole them into firing these employees so they could "be substituted by alien enemies who would be paid a very low wage only."6 If the workers were fired and destitute they would have no choice but to enlist.

This scheme to work with the railway companies to replace their military aged men with internees appears to be what ultimately happened a month later, and contributed to the closing of the camp. It also can't have done much to engender good relations between the internees and the rest of Canada's working class after the war.

7. Life for the Internees

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

Several internees standing in the camp's laundry, surrounded by clothes they are attempting to dry before the next day's labour. The conditions that the internees were expected to work under were deplorable. Their diet consisted of fewer calories than the government recognized was r equired to support a man labouring, and the food they did receive was of poor quality. Hunger was a constant complaint. The weather conditions were also a problem. They had inadequate clothes but were expected to work in severely cold temperatures in the first several months of the camp's operation, and then had to work in sultry heat.

Their daily routine usually consisted of marching out from their unheated bunkhouses to a work site, followed by eight hours of work without regular breaks, and then being marched back to camp. One senior officer noted that these marches could "amount to practically a day's work in itself."1

Almost no internees left any written records of their experiences, and it is only through the stories that they told their children and relatives that we are today able to understand what their experience was like.

In Sandra Semchuk's recent book The Stories Were Not Told, Andrew Antoniuk recounts the story of his uncle who was interned here. It provides a rare glimpse inside the camp. "He felt he was a slave labourer there in the internment camp in Jasper National Park."

* * *

The story of Jasper internee Yuro Forchuk is also related in Semchuk's book by his son Marshall.

"He used to cut and carry logs. They had to make their own furnishings and build their own buildings. He was building bridges—the railroad was passing through, so trestles and bridges had to be built, which meant cutting timber—squaring timber when you got it… They worked very, very hard. He often mentioned that it was from dark to dark.

"The winters there, as you know, Jasper is probably five, six, seven thousand feet above sea level. It would be extremely cold. My dad suffered in those days from what we call rheumata, rheumatism. It was a hard life. Dad came out of there, suffering from rheumatism. They would adapt as best as they could using what was available.

The overwhelming impression left on Marshall's father and Andrew's uncle was the injustice and shame of it all.

As Andrew recounts:

"My uncle was so distraught. He saw no reason for this. He was against what happened in Europe. The Austrians took the country (Ukraine) away - he did not support the government. He just could not believe that he was an enemy alien seen to be supporting the German-Austro War. It just didn't make sense and that's why he was so humiliated."

Marshall said of his father:

"Being detained, being jailed is, can never be a happy experience, but being detained, losing everything you've got and not knowing why, except the fact you did not do anything wrong. My dad didn't do anything wrong. He lost his homestead; he lost everything that he had there. He was just taken and put to work in a prison camp for twenty-five cents a day in the cold of a Jasper winter. It is cold in the Rockies. Even though he knew he had done nothing wrong, there was shame attached.

"My dad used to say, "Chuho un a taser a bella?" "Why did they do this?" And to this day I think, "Why did this do this?" Why do people do cruel things? Why does government do the cruelties they do? Why, why, why?"4

8. Refusing to Work

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

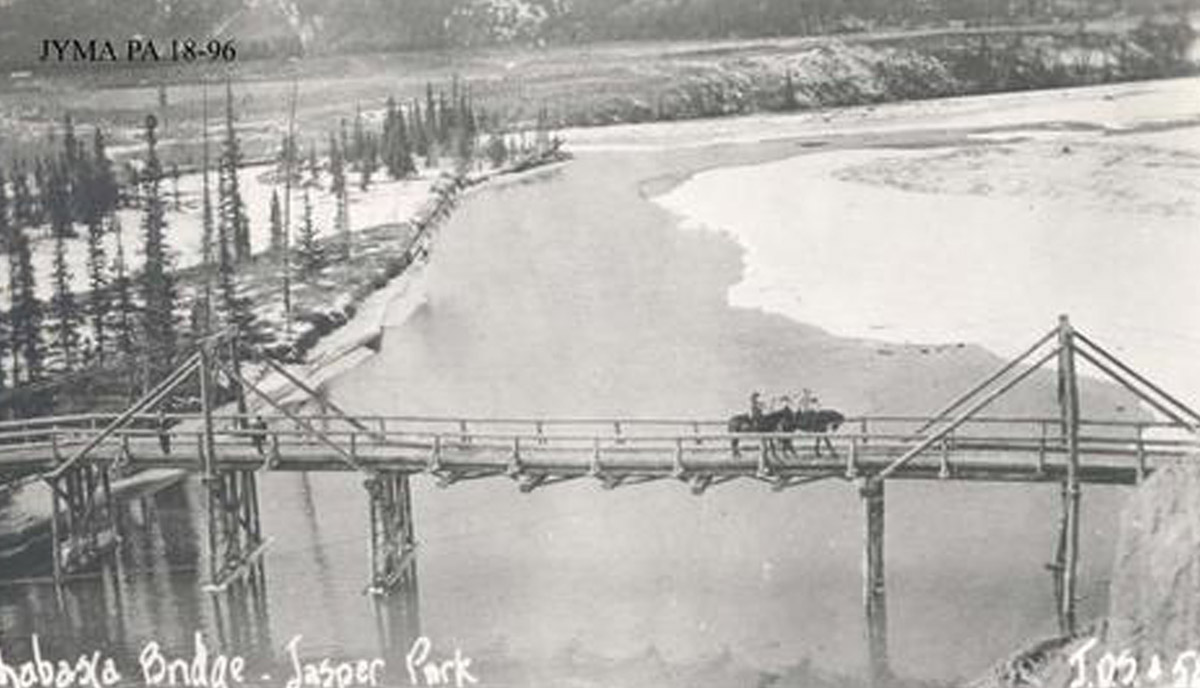

This was the bridge across the Athabasca on the Old Fort Point Road that was worked on by the internees. The current bridge was built in the 1930s.

The Jasper camp was not a success. During the spring of 1916 the internees went on hunger strike in protest about the poor quality of food and were soon "locked in a war of wills" with the camp's guards and officers.1 It was the first such strike in one of the Dominion Parks Branch's forced labour camps. As the work in the main Jasper camp ground to a halt, a small satellite camp set up at Maligne Lake was completely crippled by strikes.

The anodyne language in the Dominion Parks Branch's 1916 annual report explains the result:

"The construction of the road to Medicine Lake was to have been accomplished by means of alien labour, but owing to difficulty with the prisoners only from 10% to 15% of the number interned at the Maligne camp were available for roadwork. As it was of no advantage to the Parks department to continue the camp under these conditions, work was closed down on August 15th and the camp subsequently disbanded."2

It quickly became apparent that the entire scheme was becoming untenable. The Parks overseers blamed the camp's commandant, Major Hopkins, for failing to overcome the prisoners' resistance. Later, an intrigue was to come to light indicating that the major's adjutant, Lieutenant Bury, was conspiring with Parks staff to take the commandant's job. They apparently believed the ambitious young lieutenant would be more effective in extracting labour from the internees.

* * *

This may come as a surprise since we have been describing these as forced labour camps. The issue is a little more complex. It was Canada's international position, and in keeping with international law, that labour in these camps was not compulsory or coerced. However, Otter was also under intense pressure from the Dominion Parks Branch and the provincial governments to ensure work quotas were met.

It seems a compromise was found, where Otter carefully avoided giving direct orders on the severity of measures to use to ensure work quotas were met. At the same time he promoted those officers who used brutal methods and met said quotas. Those who failed to get the prisoners to work were fired, and these usually happened to be the ones who were soft on the prisoners.

A senior officer at Kapuskasing wrote to Otter "the basis of the discontent seems to be that the interned aliens are compelled to work." The officer asked for specific instructions on what methods were permitted to force work. Otter responded "it has not been considered advisable to promulgate any definite order upon [what can be done to force them to work], while on the other hand it is better for both themselves and the public that they should. Therefore, the matter has been left to the tact and judgment of Commandants."3

While divesting himself of responsibility for what was happening in the camps, he was clearly aware that abuses were widespread. He wrote to a neutral consul:

"The various complaints made to you by the prisoners as to the rough conduct of the guards, I fear, is not altogether without reason, a fact much to be regretted and, I am sorry to say, by no means an uncommon occurrence at other Stations."

Yet he did little to curtail any of this "rough conduct", and the abuses continued throughout.4

In Otter's final report on internment operations at the end of the war he no longer regretted anything that had happened under his command. "Apart from the natural irritation consequent upon a deprivation of liberty, the general disposition of prisoners was philosophical acceptance of the situation, the policy adopted being that of humane treatment throughout." He asserted that "little complaint can be made," about the treatment of internees.5

"There were of course a number of very vicious and insubordinate characters with whom stringent measures had to be adopted, particularly when the daily ration of food was reduced, and again over a question of what constituted obligatory and what voluntary labour, resulting in each insta nce in an incipient insurrection easily quelled."6

Otter would also fire commandants if they weren't getting the internees to work hard enough. When the camp commandant at Mount Revelstoke camp failed to severely punish blacksmiths who went on strike, Commissioner Harkin complained to General Otter. Otter responded by firing the commandant, writing "the Dominion Parks Commission, for whom work is being done by the prisoners under his charge, greatly complain that results are not being obtained by their labour commensurate with the expenditure entailed, though the lack of energy, and indifference of this officer."7

At the Edgewood camp, the Parks superintendent complained that Commandant Harvey "petted" the prisoners. The superintendent wrote to Harkin approvingly about one Lt. Brooks who had taken over during a temporary absence by the commandant. The lieutenant was much quicker to put obstinate internees on punishment diets of bread and water and frequently threatened the internees with beatings. While these policies actually made the situation worse and caused the strike to spread, the superintendent was impressed: "Brooks is handling the situation in the proper way and if left alone will get the results we want… Can you support him for commandant of this camp?"8

For these same reasons, Commandant Hopkins in Jasper seems to have been about to suffer a kind of coup at the hands of his adjutant and the Parks superintendent. However, before that could happen Otter had decided to cut his losses and close the Jasper camp entirely.

9. The End of the Camp

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

A view of the Athabasca River and the bridge that the internees repaired across it.

By the time the internment camp in Jasper had opened in 1916, it had already become clear that the internee labour camps were becoming unnecessary due to the shortage of workers. Canada was already struggling to meet the recruitment quotas set for the war in Europe, and industry was clamouring for access to this pool of enemy alien labour.

By April 1916 the government had decided to release all "non-dangerous" enemy aliens and parole them to work in various industries across Canada. There the internees were still required to report monthly to parole officers, technically forbidden from leaving their jobs (though this proved impossible to enforce), and frequently abused by their employers. But they were theoretically to be paid market wages, and not forced to live under the harsh military discipline of the camps.

When the camp closed in August 1916, all but 22 of Jasper's 208 internees were paroled to work in the railways, at coal mines, and on various farms around Alberta. The remaining 22 were considered "dangerous" and sent to the Lethbridge camp.

* * *

"The internment camp at Jasper has been broken up and the inmates sent to different quarters, some sent to Lethbridge, while others—perhaps what are considered the least dangerous—have been engaged by the CPR and GTP railways to do work on their lines, and will report at intervals to the department according to the laws and regulations governing aliens in this country. Those of the officers in charge of the camp who are physically fit will enlist in overseas battalions, although those who have been in charge are mostly returned soldiers and men who have already offered their services overseas and were rejected.

"From 200 to 208 men have been at the camp at Jasper, and since this has been opened a great deal of work has been done to the townsite."1

The war had already changed Canada. In 1914 there were too few jobs to go around. By 1916 there were not enough men to feed into the meat-grinder of the trenches, not enough men left over to guard the camps, and not enough men to work in the industries that Canada's war effort depended upon. The internees and their guards were needed elsewhere.

The internment system was quietly wound down, and the vast majority of the internees paroled and then eventually allowed to return to their ruined lives. (Though several camps did stay open until 1920 for a smaller number of socialists, communists, and 'undesirables').

The newly-released internees never received an apology or even really any kind of acknowledgement or explanation of what had happened. Though their treatment had been the result of a shocking and abrupt near-total suspension of democracy and individual civil rights, and had disgraced Canada in the eyes of the world, they and their experiences were to disappear entirely from Canadians' public consciousness for the next 50 years.

10. Legacies

Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association

1916

Two horsemen on the Athabasca Bridge.

In May 1917 the Edmonton Journal quoted a speech given by a representative of the Dominion Parks Branch:

"I have come to remind you of the wonderful playgrounds right at your own front door… Grander, vaster and more glorious scenic beauty than Switzerland with its alps… All these scenic features have been opened up by scenic roads and trails… most wonderful scenes await the tourist and the Canadian."1

As Waiser writes of the camps:

"The cruellest blow was being confined in what were being widely promoted as Canada's national playgrounds. For several years thereafter, the words 'these are your parks… Come and enjoy them' would haunt many immigrants who, despite their wartime treatment, had decided to make Canada their home."2

The development of Canada's national parks would utilize camp labour again with the 'relief camps' of the Great Depression, and then with Japanese internees during the Second World War.

* * *

Almost universally the internees kept a low profile till their dying day. They lived in fear of Canada once again breaking its promise and turning on them.

The experience changed Marshall Forchuk's father forever.

"Your question is, 'What was his name?' What did he change his name to? Dad lost more than five years. He lost more than his homestead and the horses and the cattle that he had. He lost his identity. He had to become someone else because, even when he relocated later, in civilization he could not be the same person because he did not know who his enemies were. He had to be a frightened man. I don't know, to this day, I don't know for sure what my Dad's original name was...

"You can steal my wallet, steal my car, and I can get another. But when you steal my identity. When you steal my name, and I asked you before we began, 'What is the worst thing the white man ever did to the Indian when he came here?'... The worst thing we did as a 'civilization' or lack of civilization, was to steal the Indian's identity. We tried to make them something else… We stole their identity and we knew that we were stealing their identity."3

Donate Now

If you enjoyed this free content, we ask you to consider making a donation to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, which is providing urgently needed humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

The Ukrainian people are heroically defending their homeland against a genocidal war of Russian aggression. The humanitarian situation is critical and the needs immense. 100% of all donations made through this link go directly to supporting the people of Ukraine. Recently funded initiatives by the Canada-Ukraine Foundation include demining and removal of unexploded ordnance, and the evacuation of thousands of deaf people from the warzone.

Endnotes

2. Austro-Hungarians in Canada

1. Lubomyr Luciuk, *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920,* (Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001), 30.

3. Interning the Destitute

1. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 30.

2. Desmond Morton. "Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada during the First World War," *Canadian Historical Review,* (Vol. 55 Issue 1, March 1973 pp.32-58), 32.

3. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 33.

5. Luciuk, In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence, 67.

4. The Park Plans

1. "Prisoners will be Kept Active at Jasper," *Edmonton Journal*, February 3, 1916, online.

2. Bohdan S. Kordan, *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience,* (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016), 116.

3. Bill Waiser, *Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada's National Parks,* (Toronto: Fifth House Publishing, 1995), 25.

4. "Alien Enemies Build Park Roads," Brandon Daily Sun, January 11, 1916, online.

5. The Camp Opens

1. "Jasper Internment Camp Closed, Prisoners at Work," *Edmonton Journal*, September 4, 1916, online.

2. "Several Hundred Enemy Aliens to be Interned," *Edmonton Journal*, October 9, 1915, online.

3. Waiser, 25.

4. Waiser, 25.

6. Finding Guards

1. "Returned Soldiers Sign up as Guards at Jasper Park," *Edmonton Journal*, January 15, 1916, online.

2. "Returned Soldiers Sign up as Guards at Jasper Park," *Edmonton Journal*, January 15, 1916, online.

3. Waiser, 25.

4. "Guards Wanted," *Edmonton Bulletin*, March 15, 1916, online.

5. Kordan, 166.

6. "Recruiting Problems Discussed," Edmonton Bulletin, July 6, 1916, online.

7. Life for the Internees

1. Kordan, 164.

2. Sandra Semchuk, *Their Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps,* (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019), 128-131.

3. Semchuk, 132-135.

8. Refusing to Work

1. Waiser, 33.

2. James Harkin, "Annual Report of Surveys and Constructions of Highways in the Dominion Parks - 1916," *Dominion Parks Branch*, (Ottawa, 1916), 9. http://parkscanadahistory.com/publications/ann-rpt-hwy-1916.pdf

3. Kordan, 193.

5. V.J. Kaye & J.B. Gregorovitch, eds, *Ukrainian Canadians in Canada's Wars: Materials for Ukrainian History,* (Toronto: Ukrainian Canadian Research Foundation, 1983), 81.

6. V.J. Kaye & J.B. Gregorovicth, 80.

7. Kordan, 171.

8. Kordan, 172.

9. The End of the Camp

1. "Jasper Internment Camp Closed, Prisoners at Work," *Edmonton Journal*, September 4, 1916, online.

10. Legacies

1. "An Interesting Talk on the National Parks of Canada," *Red Deer News*, May 16, 1917, online.

2. Waiser, 47.

3. Semchuk, 135.

Bibliography

Harkin, James. "Annual Report of Surveys and Constructions of Highways in the Dominion Parks - 1916." *Dominion Parks Branch*. Ottawa, 1916. http://parkscanadahistory.com/publications/ann-rpt-hwy-1916.pdf

Kaye V.J. & Gregorovitch J.B. , eds. *Ukrainian Canadians in Canada's Wars: Materials for Ukrainian History.* Toronto: Ukrainian Canadian Research Foundation, 1983

Kordan, Bohdan S. *No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience.* Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2016.

Luciuk, Lubomyr. *In Fear of the Barbed Wire Fence: Canada's First National Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians 1914-1920.* Toronto: Kashtan Press, 2001.

Morton, Desmond. "Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada during the First World War." *Canadian Historical Review.* Vol. 55 Issue 1, March 1973 pp.32-58.

Semchuk, Sandra. *Their Stories Were Not Told: Canada's First World War Internment Camps.* Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2019.

Waiser, Bill. *Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada's National Parks.* Toronto: Fifth House Publishing, 1995.

**Newspaper Articles**

"Alien Enemies Build Park Roads." *Brandon Daily Sun*. January 11, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-01-11-BDS-Alien-Enemies-Build-Park-Roads.pdf

"An Interesting Talk on the National Parks of Canada." *Red Deer News*. May 16, 1917. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1917-05-16-RDN-An-Interesting-Talk-on-the-National-Parks-of-Canada.pdf

"Guards Wanted." *Edmonton Bulletin.* March 15, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-03-15-EB-Guards-Wanted.pdf

"Jasper Internment Camp Closed, Prisoners at Work." *Edmonton Journal*. September 4, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-09-04-EB-Jasper-Internment-Camp-Closed-Prisoners-at-Work.pdf

"Prisoners will be Kept Active at Jasper." *Edmonton Journal*. February 3, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-02-03-EJ-Prisoners-Will-be-Kept-Active-at-Jasper-Camp.pdf

"Recruiting Problems Discussed." Edmonton Bulletin. July 6, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-07-06-EB-Recruiting-Problems-Discussed.pdf

"Returned Soldiers Sign up as Guards at Jasper Park." *Edmonton Journal*. January 15, 1916. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1916-01-15-EJ-Returned-Soldiers-Sign-up-as-Guards-at-Jasper-Park.pdf

"Several Hundred Enemy Aliens to be Interned." *Edmonton Journal*. October 9, 1915. https://www.internmentcanada.ca/articles/12/1915-10-09-EJ-Several-Hundred-Alien-Enemies-to-be-Interned.pdf