Walking Tour

Real Estate Speculation

A City Built on Property Values

Andrew Farris

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P210

"It is the English-speaking world's favourite game: property," writes the economic historian Niall Ferguson. "No other facet of financial life has such a hold on the popular imagination. No other asset-allocation decision has inspired so many dinner-party conversations. The real estate market is unique. Every adult, no matter how economically illiterate, has a view on its future prospects."1

In few cities can this be as true as Vancouver. From the city's founding in 1886, Vancouverites have had an almost neurotic obsession with their property values. Many of the defining events in this city's early history, from the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the establishment of Stanley Park, to the city's layout and the name "Vancouver" itself, are all connected to the buying and selling of real estate.

One of the defining events in Vancouver history, perhaps the most important event that most people today have never heard of, was the real estate bubble of 1905-1913. It coincided with the biggest economic boom in Vancouver's history, when tens of thousands of new immigrants arrived and vast new tracts of land were opened up for settlement. Foreign money from Britain poured in, sending real estate prices through the roof, while shady realtors encouraged Vancouverites from all walks of life to invest their life savings in buying up speculative plots of land on the fringes of town. The speculative fever infected society, and thousands made off with fortunes they scarcely could have dreamed of a few short years before. Thousands more were left destitute, priced out of the market by soaring property taxes and rents.

Then in 1913 the global economy went into recession and the real estate bubble burst. The shock was a body blow to Vancouver's skyrocketing economy. A cascading series of bank failures led to a complete collapse in real estate prices and high unemployment. The building boom ground to a halt and few new buildings were to be erected for decades. In some regards the city would not make up all the ground lost until after World War II.

Today real estate has once again become the top topic of dinner-table conversation. Prices continue to rise at breakneck speed, fuelled by a torrent of foreign money, this time from China. Many of the same trends seem to be in play today and one can't help but feel unease about the many parallels between 1912 and 2016.

In this tour we will learn first about how real estate speculation shaped Vancouver's first years and laid the groundwork for the modern city. Then we will examine the real estate bubble from 1905 to 1913, learning how it happened and what it was like to live through. Are there lessons we can learn from the popping of Vancouver's first real estate bubble?

This project is a partnership with the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association.

1. A Promising Future

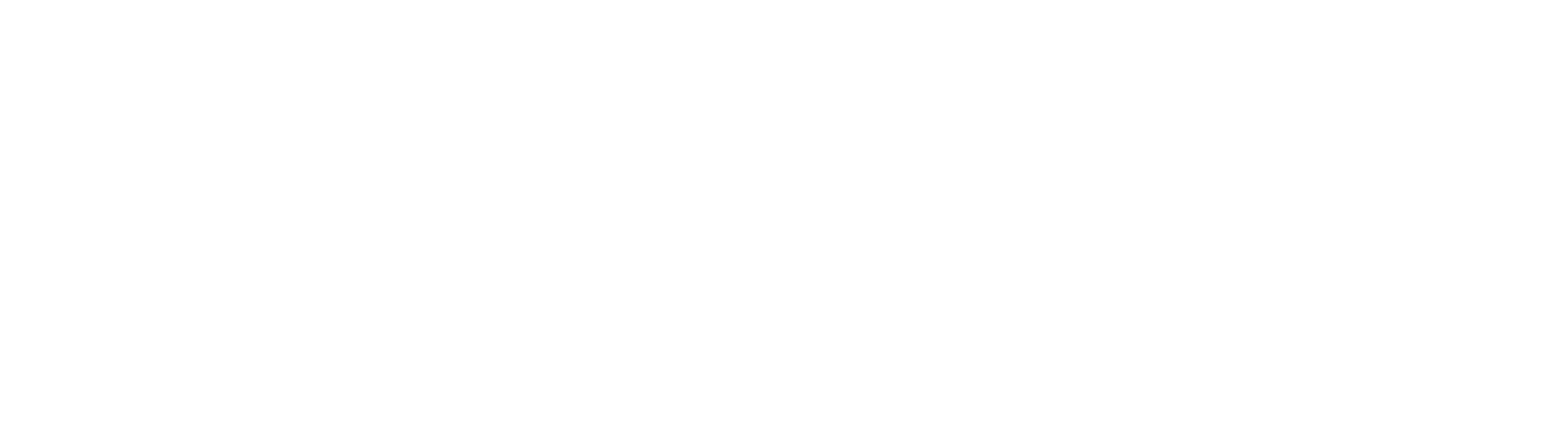

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Tr P13

1886

A giant Douglas fir felled at the intersection of Granville and Georgia. From the very beginning, the business of Vancouver was real estate. A series of momentous events in the mid-1880s, from the naming of the city to the establishment of Stanley Park, all resulted from real estate plays. The one with the most far-reaching effects involved the choice of terminus city for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

* * *

At almost a million square kilometres, British Columbia is massive. If it was a country it would be the 30th largest in the world. Yet the 1881 census counted less than 50,000 inhabitants spread thinly across a handful of coastal settlements and First Nations villages.1 2 Practically the entire province had yet to be mapped. What untold riches of timber, metal, coal and fish remained to be discovered? Surely, whichever city the CPR chose as the railway terminus was destined to become the commercial hub for the exploitation and export of these invaluable resources. Everyone seemed convinced it must eventually become a global metropolis.

Vancouver (which was then known as Granville), Port Moody, New Westminster, and even Victoria, vigorously competed for the nod. Who would the railway pick?

2. The Terminus City

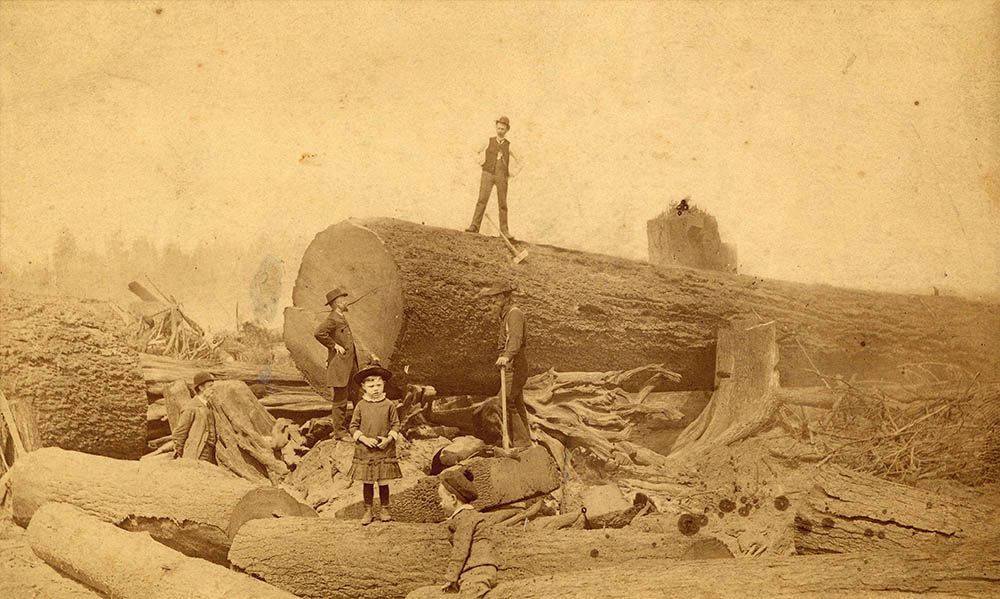

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: LGN 453

1886

The real estate speculator James Welton Horne, standing in the middle facing the camera, pours over a map of Vancouver. Horne and his colleagues have posed for this photo at the temporary 'office' they've set up at the giant Fir trunk. J.W. Horne, not to be confused with CPR VP William Van Horne, made one of Vancouver's first fortunes in real estate.

* * *

While Port Moody's real estate values skyrocketed as speculators fought to buy up the best tracts of land, the citizens of Granville furiously lobbied the railway to change its mind. The CPR's directors were not fools; they had already built fortunes by browbeating massive concessions out of communities across Canada who desperately wanted the railroad. They knew exactly what the land around Granville was worth.

In 1884 they told Granville's representatives they would reconsider their decision if given land—a lot of it. The Granvilleans breathed a massive sigh of relief and signed whatever CPR Vice-President William Cornelius Van Horne thrust in front of them. For a fraction its value, they signed away half of the modern area of Vancouver, including almost all the downtown peninsula, all the land around False Creek, and most of the West Side. At a stroke the big city dreams of Port Moody were dashed and the bright future of Granville assured. Yet both cities had been had: The CPR always intended to make Granville the terminus, but promising the reward to the city over the hill was a highly effective negotiating tactic.2

As if to remind everyone just who was now in charge, Van Horne deemed Granville too boring a name and thought if the city was going to grow and prosper—and the CPR's land holdings increase in value—it would need a catchier name. Every British schoolchild knew of Captain George Vancouver's legendary voyages of discovery, so Vancouver it was.3 The people of Granville didn't mind, they were just happy to be getting the railway.

3. The CPR's Master Plan

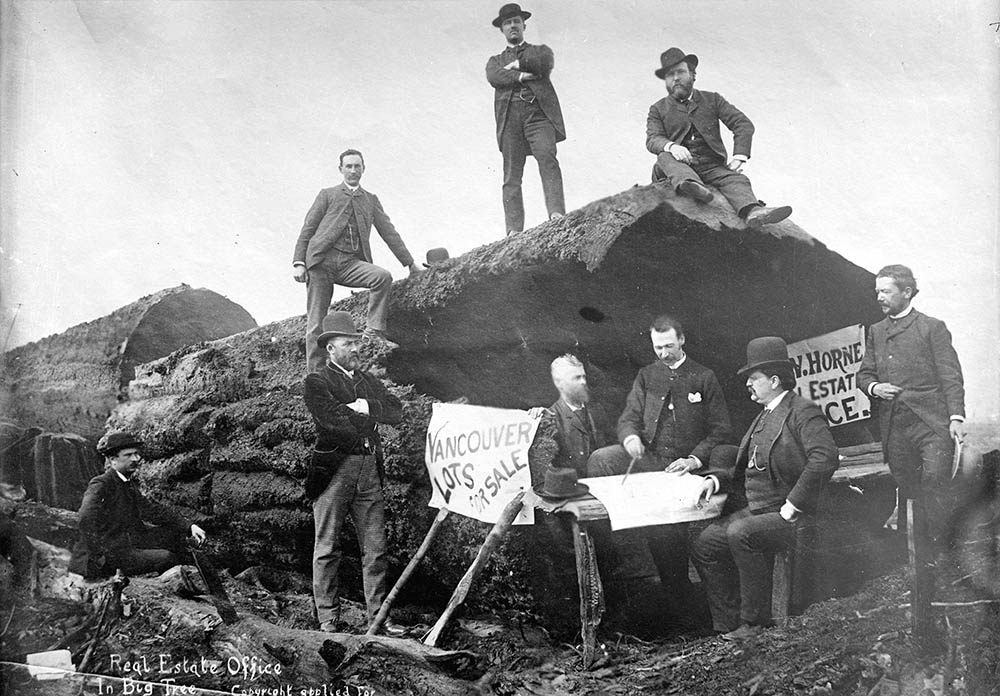

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Hot P14

1886

Workers take a break from clearing land on what would eventually become the first Hotel Vancouver at Granville and Georgia. Now that the CPR owned much of the Vancouver peninsula, the hotel they built at its highest point was a bold declaration that Vancouver's future commercial centre was to be here, and not Gastown. To get the most value out of their new giant properties, the CPR had a master plan for Vancouver's future. That plan has defined the city we know today.

* * *

They set to work clearing the land for building, cutting down the trees, burning the mountains of branches and blowing up the stumps. It was these clearing fires, one at Cambie and Cordova and another near the Yaletown Roundhouse that caused the Great Fire of Vancouver in June 1886 and burned the entire city to the ground.

Nevertheless the city rebuilt in weeks and clearing of the peninsula continued. It was in those months after the fire that the photo above was taken. The decision to build the first Hotel Vancouver here sent a powerful signal that this was the new downtown, and in response land values started to rise. In the 1870s land here could be bought for $1 an acre. In 1886 a lot around Granville and Dunsmuir was valued at $400. By 1893 it was $1,100.

The local superintendent Harry Abbott noticed during the first CPR land auction in 1886 that speculators "had seized upon all the best sites without any intention of putting up buildings." Though the CPR had massive land holdings all across Canada, by 1889 their sales of Vancouver land had generated bigger profits than those in all the other cities combined.1

4. The Purpose of Stanley Park

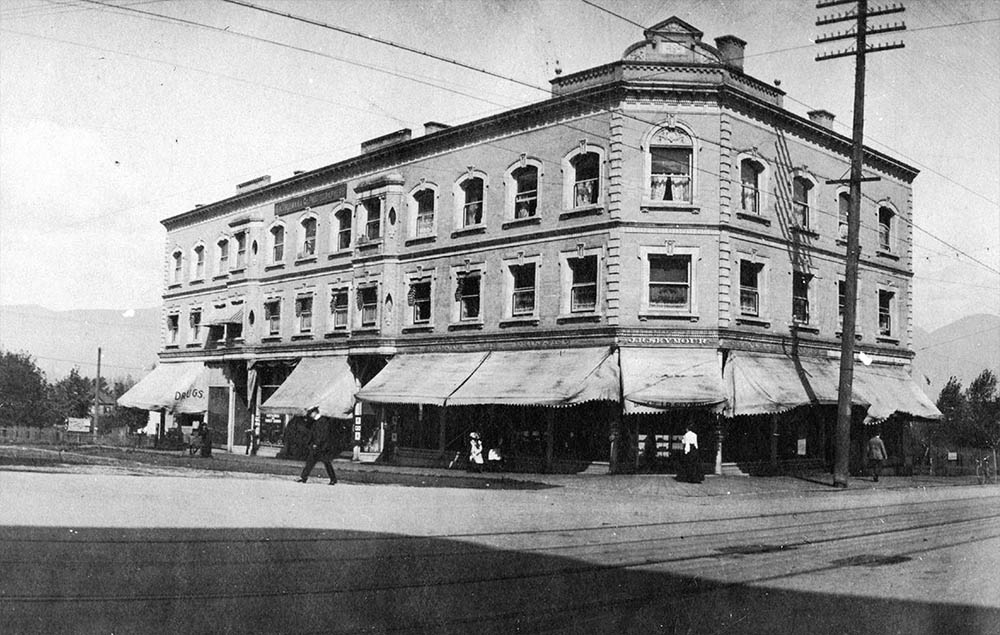

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P76

1900s

A new building at the corner of Granville and Georgia is a sign that the CPR's plan to build up this part of town was working. Yet the other landowners in the city, who included much of Vancouver's city council, wanted to protect the value of their land. This desire led to the creation of Stanley Park, which would be visible on the other side of this building.

* * *

So at the very first city council meeting in April 1886, they voted to take over the military reserve from the government for $1 a year and turn it into a public park. We must be infinitely grateful that they did. It is impossible to imagine Vancouver today without Stanley Park, the jewel of Vancouver, and it is frequently rated the best park in the world.3 It's interesting to consider that this must be one of the very few decisions where naked financial self-interest has left a legacy of stunning natural beauty for future generations.

5. Real Estate Fever

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: LGN 482

1890

A line of freshly-built townhouses in the downtown peninsula. In the late 1880s and early 1890s most everyone in Vancouver caught real estate fever. People purchased land only to flip it months later and make huge profits. Real estate offices were everywhere—in 1887 there were more real estate firms than grocery stores—and everyone with money to spare was investing in land.1 The prevailing attitude was that "you're a mug if you invest in anything else."2

* * *

Even the panegyrist of British imperialism, Rudyard Kipling, got swept up in the mania. While on a tour of Canada in 1889, the world-renowned author described how he was persuaded to buy two lots on Fraser and 11th Street, though he never intended to live there.

"All the Boy said was: 'I give you my word it isn't on a cliff or under water, and before long the town ought to move out that way. I'd advise you to take it.' And I took it as easily as a man buys a piece of tobacco. Me voici, owner of some four hundred well-developed pines, a few thousand tons of granite scattered in blocks at the roots of the pines, and a sprinkling of earth. That's a townlot in Vancouver. You or your agent hold to it till property rises, then sell out and buy more land further out of town and repeat the process. I do not quite see how this sort of thing helps the growth of a town, but the English Boy says that it is the ‘essence of speculation,' so it must be all right."4

Kipling also purchased 20 acres in North Vancouver and sat on it for 20 years, paying taxes all the while. When he finally went to sell it in the 1920s he discovered that someone else actually owned the land; the realtor had ripped him off.5

6. Neighbourhoods Take Shape

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Bu P74.1

1894

A well-appointed boarding house on the corner of Georgia and Cambie. Though the real estate market ground to a halt following the Great Panic of 1893, the CPR still wielded immense wealth and influence. Their master plan for Vancouver began to take shape and the contours of modern Vancouver came into view: the posh West End, the working-class East End and industrialized False Creek

* * *

One observer compared it to the East End:

"The West End is the home of the merchant and professional man, the East, that of the lumber king and mechanic… Somewhat unsightly are some parts of the East End. Huge lumber mills, some of which are unadorned with paint or whitewash and from which the ungainly smokestacks pierce the lower clouds; countless piles of lumber, freshly sawn and stored up for use in case of emergency are, only to those immediately interested, very beautiful to look at. More inviting are the blocks of wooden homes, the comfortable abode of hundreds of operatives. And occasionally we have blocks of handsome dwellings approaching in grandeur and elegance some of the homes of our aristocrats of the West End."

The CPR decided that False Creek to the south would be Vancouver's industrial heartland. This decision was greeted with horror by some of the locals who had settled on the south side of the creek. They so loved the spot they named the districts Mount Pleasant and Fairview, fully expecting them to become beautiful upper class neighbourhoods.

Nevertheless, since the CPR owned the entire basin they had the final word, and industrialize False Creek they did. Writing in the 1970s, the historian Julie Cruikshank noted how in the 1890s it was "described as a beautiful setting overlooking blue waters, surrounded by tall stands of forests. It is difficult to imagine this in view of the current environmental horror in the False Creek area." Mount Pleasant and Fairview were always hobbled by their close proximity to this heavy industry, which turned the creek into a toxic cesspit. It has only been since the 1980s that False Creek's remarkably successful environmental cleanup has once again made these neighbourhoods nice places to live.1

7. Blowing Bubbles

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-2-: CVA 371-1274

1911

The steel frame construction of the World Tower (today's Sun Tower). It was one of Vancouver's first skyscrapers and for a time the tallest building in the British Empire. It was representative of a time of phenomenal growth and optimism, when the population quadrupled in ten years to over 100,000 and a real estate bubble flew out of control. Property prices rose faster than at any time in Vancouver's history before or since. The boom was so stunning that many people at the time concluded it could only end with Vancouver as one of the leading global centres of trade and finance.1 It's of considerable interest to us today then that that is not how the boom ended. Instead, in 1913, the colossal real estate bubble popped, sending Vancouver's economy into a tailspin that would take almost 40 years to recover from.

* * *

Most of these foreigners were British and they brought with them connections to banks and businesses back in the mother country. They looked at Vancouver's access to abundant natural resources, lax regulations, and booming economy and concluded that Vancouver property was "a sure thing". Foreign money flooded the market, and prices began to rise. After 1905 they began to rise much more steeply. This was, in the words of one historian, "the golden age of the real estate speculator."2

A small lot on Hastings Street was purchased in 1904 for $26,000. In 1908 it was sold for $90,000. Just one year later it sold for a jaw-dropping $175,000. When the CPR auctioned off some empty lots in Kitsilano they were sold to speculators for $400 who turned around and resold them for $5,000.3

Harvey Hadden is typical of many English investors at this time. He would make periodic trips to Vancouver to purchase properties and then have his local agent, another Englishman, hold on to them for a few years before selling them. Hadden purchased one lot at the southeast corner of Hastings and Granville for $25,000, and likely overpaid by $5,000. Yet he sold it in 1913 for $750,000, netting a tidy 3,000% profit.4 5His story almost sounds familiar today if we changed Hadden's country of origin.

One realtor gushed "Do you know how I would write a dissertation on 'How to get rich in Vancouver'? Take a map of the lower peninsula, shut your eyes, stick your finger anywhere and sit tight."6

In 1909 a business survey in the Vancouver News Advertiser wrote: "With the real estate dealers 1909 has been a banner year in Vancouver. Three years ago it was prophesied that the real estate business had reached its apex and must decline; today prices have doubled and trebled and real estate brokers have probably made more money in 1909 than even in the early days of the great real estate movement about 3 years ago."7

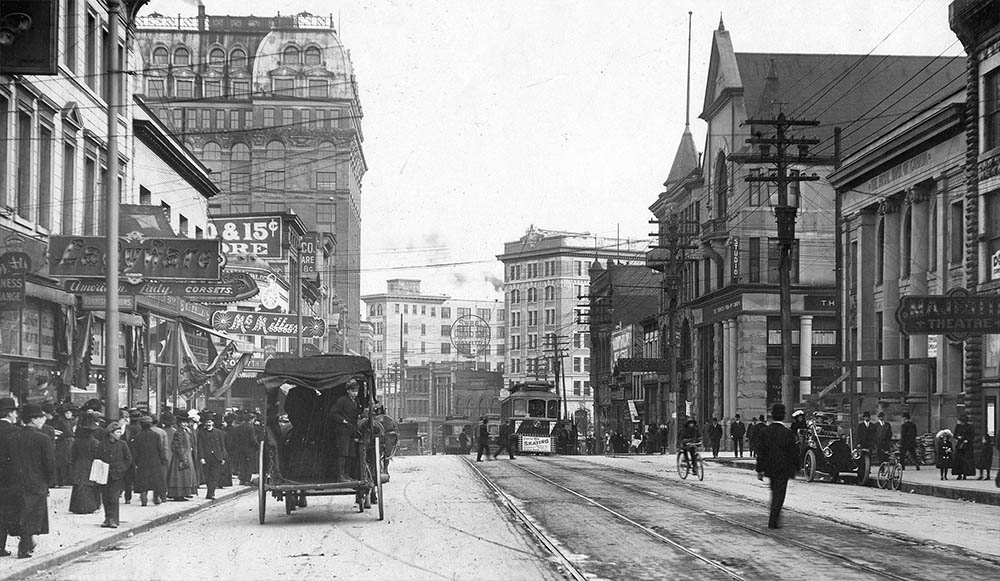

8. Building Out

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: SGN 881

1901

A street car passes by an arch erected by the Japanese Canadian community to commemorate a royal visit. As real estate prices rose the suburbs of Vancouver were opened up to settlement by street car lines and there followed a gigantic building boom to accommodate all the new arrivals. It's no exaggeration to say that at this time the "main industries" of Vancouver were real estate and building.1

* * *

Most of the buildings we are accustomed to thinking of as heritage were built in this brief period from 1900 to 1912. Downtown landmarks like the courthouse, Vancouver Block, Sun Tower and Dominion Tower were erected, while whole neighbourhoods from the West End, to Point Grey and Kerrisdale were filled out. In 1912 alone 2,224 houses were built, 217 factories, 293 offices and 218 apartment buildings.6

One interesting aspect of this growth was the unabashed collusion between local government, the B.C. Electric Railway and realtors to use street car lines as a way to speculate on real estate. Prior to 1900 Vancouver had only a couple miles of street car lines in the downtown core. After 1900, over 100 miles of street car lines were built opening up new areas to development and causing prices for the largely forested lots to skyrocket. Those who were in the know about planned line expansions made overnight fortunes. One C.M. Woodward "purchased a parcel of land in Point Grey for about $2,000, but had promptly disposed of it for $25-30,000 shortly after the completion of the B.C. Railway line in that region."7

9. The Affordability Crisis

Vancouver Archives AM1376-: CVA 1376-725

1908

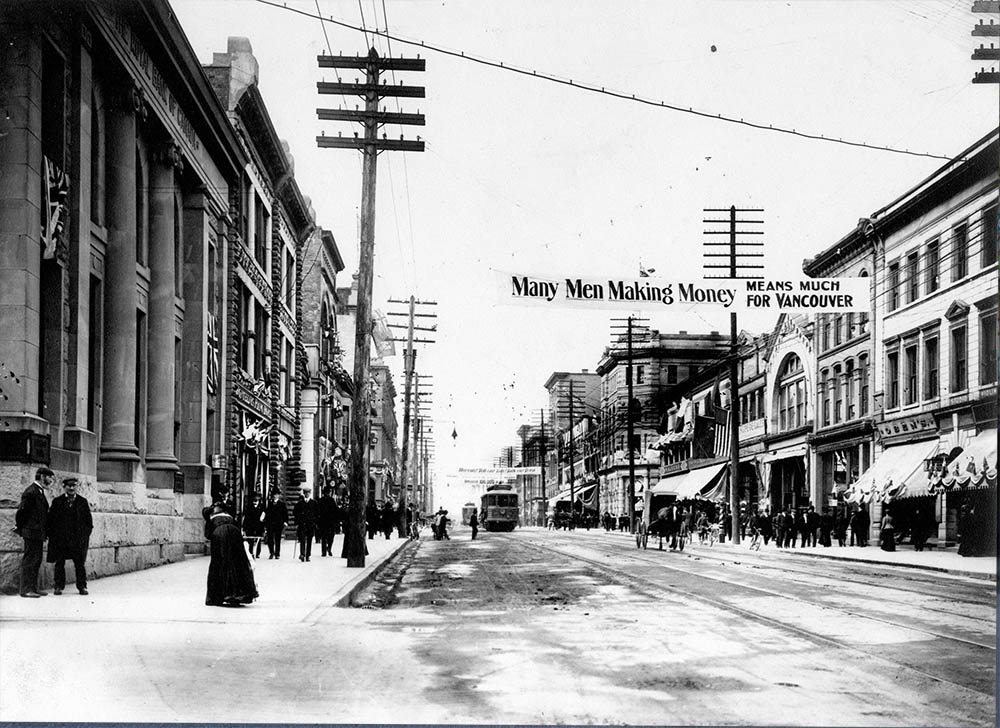

A banner hanging over Hastings Street reads "Men making money means much for Vancouver." It has been erected by the 100,000 Club, a group of Vancouver businessmen who wanted to grow the city's population to 100,000. They celebrated in 1911 when the census confirmed they had hit their target. Most of the thousands that arrived immediately found themselves priced out of the market, especially with the restrictive mortgage lending policies of the time. Nevertheless almost everyone that could threw all their money into real estate, creating a highly unstable market.

* * *

"Five year ago lots might have been purchased within the city limits for $50 each," wrote the News Advertiser in 1909. "Now it would be difficult to secure a single lot anywhere in Vancouver for less than $600." These rising prices had an immediately knock-on effect for rents. The American consul wrote to Washington pleading for a salary increase to pay his rent: it had just jumped from $30 to $45 and he couldn't make ends meet.2

In an era before social housing—or anything like what we would recognize as a social safety net—the poor were told to stop whining about the high prices, pull up their bootstraps, and invest in real estate. R.J. McDougall, writing in BC Real Estate in 1911, could barely contain his scorn with those who had the temerity to complain about spiralling prices.

“Land prices are high, it is said, higher than anything would warrant. 'Why, the workingmen cannot afford to pay at the rate demanded for these tiny outside lots,' asserted one man recently. The same thing was said here twenty years ago, answer the pioneers; others of us know that it was repeated ten years ago and five years ago, and our children and our children's children will hear the same tale of woe decades hence.

"We live in the land of destiny. In the land of wealth where, though gold is not idly picked off the rocks or from the pavements in the streets, it is just as surely gained from the platted acres and twenty-footers around us. One day an artisan may put the scanty savings of a lifetime into a tiny holding out among the evergreens, and on the morrow almost, he is building city blocks from the proceeds thereof.”3

McDougall's attitude was not unusual. Vancouver boasted twice as many real estate brokerages for its population than any other Canadian city.4 These predatory brokers formed a "floating army of land sharks swarming hungrily," arm-twisting the working classes into investing what little they had in real estate.5

A government study in 1912 was alarmed to find Vancouverites were bankrupting themselves to buy real estate. The situation was quickly reaching "crisis" proportions: 40% of land purchases were made by working class people egged on by shady realtors. The novelist Bertrand Sinclair wrote bemusedly of Vancouver's working poor, who would "go without lunch to make payments on plots of land in distant suburbs."6

The house of cards was beginning to teeter.

10. Pop!

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str P210

1910

Looking back down Hastings towards the Dominion Building in 1910. This beautiful skyscraper, recently completed when this photograph was taken, was owned by the Dominion Trust Company, which in little more than a decade rode the wave of real estate speculation from nothing into a financial behemoth. The opulent building symbolized the fantastic wealth to be won from playing the property game. It also came to symbolize hubris, and an economic model that was a "thrilling but brief ride to economic disaster."1 The Dominion Trust Company was British Columbia's Lehman Brothers.

* * *

Vancouverites awoke to economic reality in mid-1913. A financial crisis on Wall Street sent shockwaves around the global economy causing foreign investment to dry up almost overnight. Commodity prices nose-dived, while debris from railway construction clogged the Fraser River at Hell's Gate, destroying that year's salmon run and bankrupting many fishermen. British Columbia's export-led economy suddenly shuddered to a halt and fell into a deep recession.3

Thousands were thrown out of work and started defaulting on their property loans. Strikes and labour unrest convulsed the province. Commercial rents declined by half as consumer spending dried up and businesses were forced to shutter. The heavily exposed Dominion Trust Company, who couldn't even find tenants for their fancy new building, completely collapsed. This set off a cascading series of bank failures as panic spread across the economy. Lenders like the National Finance Company and the Bank of Vancouver fell apart. Dominion Trust's vice-president shot himself in his Shaugnessey mansion.

The building boom stopped dead in its tracks as construction companies ran out of money. Building permits shriveled from 1912's all-time high of $20 million to below $1 million by 1916.4

Real estate prices fell by up to 90%. A lot on Cambie and Broadway originally listed for $90,000 eventually sold for less than $8,000.5 Thousands of property owners failed to pay the property taxes on the empty speculative lots they had been encouraged to buy, causing municipalities to go bankrupt. In 1919 fully 2,000 lots were seized and auctioned off for non-payment of property taxes. Some were in arrears for as little as $10.6

Vancouver's cityscape suddenly froze in time. Huge parceled out subdivisions in the suburbs remained empty, some for almost half a century. Few new buildings were erected downtown for decades. In 1912 Vancouver's skyline was dominated by the Hotel Vancouver, the Sun Tower, the Dominion Tower, the Birks Building, and the Vancouver Block which had all been built in quick succession. That skyline would remain largely unchanged until after World War II.

11. Lessons for Today

Vancouver Archives AM54-S4-: Str N74

1898

A man walks down Hastings Street. The sign on the side of the building advertises Vancouver Loan, Trust, Savings, offering a host of financial services for property owners. Dozens of businesses like this one collapsed in 1913. Are there lessons we can learn from Vancouver's biggest real estate bubble?

* * *

Some use this ever-present debate over housing affordability to argue that the current housing market is not unusual. Yet this misses the extreme nature of our current situation. None of these other events had a speculative bubble comparable in size to the one we are living through today. The only historical parallel is the 1905-1913 real estate bubble. It seems worthwhile to see there are any lessons to be learned from it. Of course our economic circumstances today are different from what they were a century ago, and we must be cautious when drawing direct comparisons.

Yet if there is a lesson to be found here, it might be that allowing huge amounts of foreign money into the real estate market and encouraging an atmosphere of frenzied speculation can cause people to overinvest in property in the expectation property values will always rise. This might expose financial institutions and property owners to rising mortgages rates and property taxes, while many more are priced out of the market entirely. Surging property values may paper over these growing imbalances for a time, but the higher they, go the more vulnerable society becomes to global economic forces beyond its immediately control. At this point it could be the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings in Japan (or China) that starts the hurricane.

The British travel writer W. Way Elkington visited Vancouver on the eve of the popping of the property bubble. He was fascinated by the city's real estate obsession. While visiting Brockton Point in Stanley Park he sat down on a bench beside an old man, who looked lost in melancholy thought.

"You may not believe me, sir," he said suddenly, "but when I first came through them 'Narrers' it was in a small prospector's tug, me and a party of five; an you see down there on your right where the Princess Victoria is lying, well, we landed somewheres about there, and you see farther inland, where Granville Street and Hastings Street is, well, I prospected all along there for coal! You may think I'm talking through my hat, but if you had offered to give me the whole of the ground as far as I could stake from the seashore for a hundred dollars, I wouldn't have taken it. And that place over there," he continued with a sneer, pointing at the flourishing City of North Vancouver, "I could have bought that a dozen times for a few hundred dollars, and now you can't get a building-site there for that money. Just shows you the chances a fellow misses through not knowing what's going to happen."

Reflecting on the British Columbians, Elkington continued:

"If a third of the money that is wasted each year in forcing up the value of real estate were put into industries, the province, as well as Vancouver, would more than treble its business, its population, and its capital.

"Were the British Columbians richer and had they more foresight, I am sure they would pay far more attention to the mineral resources instead of allowing the Americans to come in and take their pick of the claims, while they themselves are fighting over real estate, the booming of which is every day making living more expensive, turning hundreds of families away, and frightening others from entering Vancouver.

"Rents in Victoria and Vancouver are considerably higher than in any provincial town in England, and higher even than North or West Kensington in London. The houses are not nearly so good or so comfortable for the same price.

"In spite of the inflated price of land now in Vancouver I feel sure that any one investing in land, who is in a position to hold it for five or six years, will more than double his money; it cannot help itself, its position is unique; geographically, politically, commercially, and industrially it holds the trump cards."2

Endnotes

- 1. Ferguson, Niall. The Ascent of Money. New York: Penguin Press, 2008. P. 230.

1. A Promising Future

1. Geohive. "The 50 largest (area) countries in the world." Online.

2. BC Stats. "Census Population of BC and Canada: 1871 to 2011." Online.

2. The Terminus City

1. Vancouver World. "Vancouver City. Its Wonderful History and Future Prospects." 1891. P. 3.

2. Bannerman, Gary. Gastown: The 107 Years. Vancouver: Times of North and West Vancouver, 1974. P. 25.

3. Davis, Chuck. Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Coastal Publishing, 2011.

3. The CPR's Master Plan

1. Donaldson, Jesse. "Land of Destiny." The Dependent Magazine. 18 Jan. 2012.

4. The Purpose of Stanley Park

1. Cruikshank, Julie. From Settlement to City. 1971. P. 29.

2. Grant, P. & Dickson, L. The Stanley Park Companion. Vancouver: Bluefield Books, 2003. P. 21.

3. Judd, Amy. "Stanley Park named 'top park in the entire world'. Global News. 18 June 2014. Online.

5. Real Estate Fever

1. Donaldson.

2. Ferguson, 260.

3. Bannerman, 14.

4. Kipling, Rudyard. From Sea to Sea. No. XXVIII. Online.

5. Vancouverhistory.ca. "Rudyard Kipling in Vancouver." Online.

6. Neighbourhoods Take Shape

1. Cruikshank, 13.

7. Blowing Bubbles

1. Canada's Historic Places Register. "Dominion Building." Online.

2. Macdonald, Norbert. "A Critical Growth Cycle for Vancouver, 1900-1914." BC Studies. No. 17, Spring 1975, 26-42. P. 27.

3. Cruikshank, 15.

20. Luxton, Donald. Building the West. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2007.

4. Snyders, T,. & O'Rourke, J. Namely Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

5. Macdonald, 33.

6. Ibid.

8. Building Out

1. Macdonald, 27.

2. Ibid.

3. City of Vancouver. "Statistics on Construction Activity." Online.

4. City of Vancouver. "Building permit values hit all-time high record as Vancouver's economic growth continues." 14 Jan. 2015. Online.

5. Bank of Canada. "Inflation Calculator." Online.

6. Macdonald, 33.

7. Ibid, 30.

9. The Affordability Crisis

1. Luxton.

2. Macdonald, 30.

3. Donaldson.

4. McDonald, Robert. Making Vancouver: Class, Status and Social Boundaries, 1863-1913. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996. P. 130.

5. Idid, 131.

6. Donaldson.

10. Pop!

1. McDonald, 131.

2. Ferguson, 260.

3. Luxton.

4. Snyders & O'Rourke, 24.

5. Donaldson.

6. Davis.

11. Lessons for Today

1. Berton, Pierre. The Depression: 1929-1939. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990. P. 89.

2. Elkington, E. Way. Canada The Land of Hope. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1912. P. 160.

Bibliography

Bank of Canada. "Inflation Calculator." Online.

Bannerman, Gary. Gastown: The 107 Years. Vancouver: Times of North and West Vancouver, 1974.

BC Stats. "Census Population of BC and Canada: 1871 to 2011." Online.

Berton, Pierre. The Depression: 1929-1939. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990.

Canada's Historic Places Register. "Dominion Building." Online.

City of Vancouver. "Building permit values hit all-time high record as Vancouver's economic growth continues." 14 Jan. 2015. Online.

City of Vancouver. "Statistics on Construction Activity." Online.

Cruikshank, Julie. From Settlement to City. 1971.

Davis, Chuck. Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver. Vancouver: Coastal Publishing, 2011.

Donaldson, Jesse. "Land of Destiny." The Dependent Magazine. 18 Jan. 2012.

Elkington, E. Way. Canada The Land of Hope. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1912

Ferguson, Niall. The Ascent of Money. New York: Penguin Press, 2008.

Geohive. "The 50 largest (area) countries in the world." Online.

Grant, P. & Dickson, L. The Stanley Park Companion. Vancouver: Bluefield Books, 2003.

Judd, Amy. "Stanley Park named 'top park in the entire world'. Global News. 18 June 2014. Online.

Kipling, Rudyard. From Sea to Sea. No. XXVIII. Online.

Luxton, Donald. Building the West. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2007.

Macdonald, Norbert. "A Critical Growth Cycle for Vancouver, 1900-1914." BC Studies. No. 17, Spring 1975, 26-42.

McDonald, Robert. Making Vancouver: Class, Status and Social Boundaries, 1863-1913. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996.

Snyders, T,. & O'Rourke, J. Namely Vancouver. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2001.

Vancouverhistory.ca. "Rudyard Kipling in Vancouver." Online.

Vancouver World. "Vancouver City. Its Wonderful History and Future Prospects." 1891.